To the Editor: Recently, the number of new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections in China has been decreasing. At manuscript preparation, new cases had not been reported in Wuhan since March 18, 2020.1 As health care systems resume routine clinical activities, implementation of robust infection control measures to prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS-CoV-2 remains a top priority.2

Our dermatology department is in Wuhan, the area first and worst affected by coronavirus disease 2019 in China. We aim to share our experiences in this unique position by outlining our infection control plan. We hope that it can serve as guidance for dermatology departments and the health agencies overseeing them.

In the early days of the outbreak, high rates of nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infections were observed in health care workers. More than two-thirds of infected health care workers had contracted the virus in units without known coronavirus disease 2019 patients.3 We suspect that covert carriers of the virus may have contributed to this unchecked nosocomial spread; Qiu4 reported that 60% of infections may be asymptomatic. By remaining cognizant of this risk, even in departments not directly involved in treatment of coronavirus disease 2019, we devised the following infection control plan for our dermatology clinic:

First, an experienced infection control expert team was established. This team took responsibility for training and managing health care workers, including hand hygiene and the proper use of personal protective equipment (Supplemental Material 1 available via Mendeley at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/s3ncfct2z8/1), as well as monitoring their state of health. We also held emergency simulations outlining protocols for inpatient dermatology admissions and consultations, as well as contingency plans for exposure to SARS-CoV-2–infected patients or health care workers in dermatology clinics.

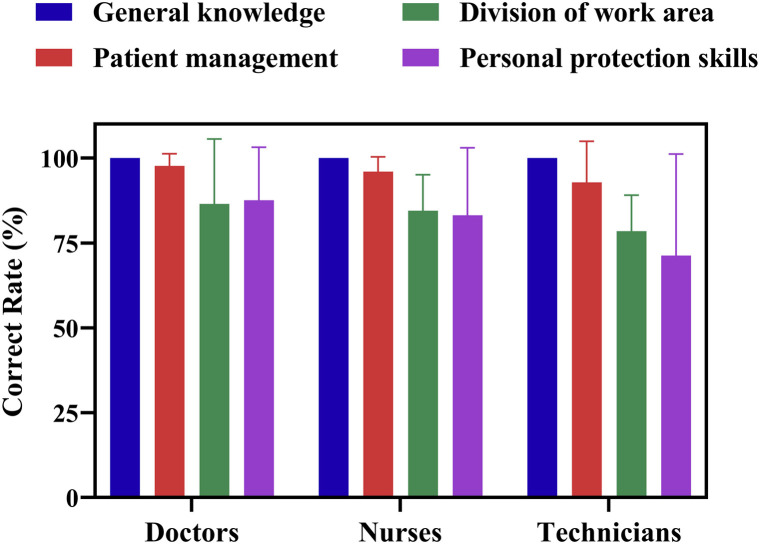

Next, the department was divided into clean, potentially contaminated, and contaminated zones. The potentially contaminated and contaminated zones were separated by 2 buffer zones (Fig 1 ). Patients and staff were to use separate passageways. Before entering the designated patient care area (contaminated zone), staff would don personal protective equipment in the clean zone. On exiting the contaminated zone, they would follow a series of transitions before returning to the clean zone. In the first buffer zone, they doffed personal protective equipment (except working clothes, N95 masks, goggles, and caps). Then they entered the potentially contaminated zone to remove the remaining items. Next, they transitioned to the second buffer zone, where they donned a new surgical mask. Only then did they enter the clean zone. This functional and geographic division of the clinics and wards was designed to minimize the risk of cross contamination. By sanitizing and washing hands in each zone and using adequate personal protective equipment for all patient encounters, we lessened the risk of nosocomial transmission.

Fig 1.

Schematic diagram of zones in the dermatology clinic and ward.

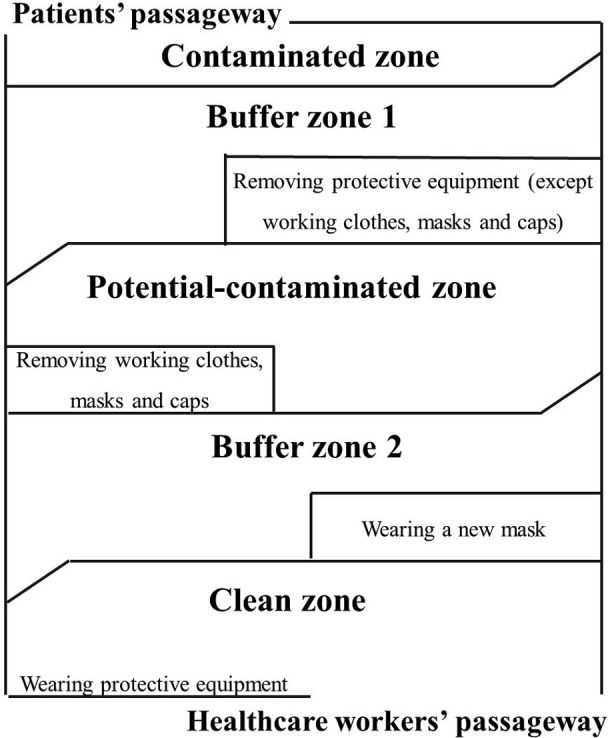

Finally, all employees were required to achieve 100% on a written examination (Supplemental Material 2). Thirty-five staff members completed the test (response rate 100%). Because of the relatively low accuracy rate of personal protective skills (82.04%) and division of work area (84.28%) (Fig 2 ), some dermatology staff received additional training.

Fig 2.

Online examination scores for doctors, nurses, and technicians in the department of dermatology.

In the fight against future outbreaks, infection-prevention strategies take precedence.2 Dermatologists should be trained in these measures, and clinics should be modified to minimize the risk of nosocomial transmission.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our deep respect for all the first-line health care workers for their dedication in the fight against SARS-CoV-2 and thank the health care workers who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Drs Zhang and Wen contributed equally to this work.

Funding sources: Supported by HUST COVID-19 Rapid Response Call Program (2020kfyXGYJ056) and Hubei Provincial Emergency Science and Technology Program for COVID-19 (2020FCA037).

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

References

- 1.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) — China, 2020. China CDC Weekly. 2020;2:113–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowdle A., Munoz-Price L.S. Preventing infection of patients and healthcare workers should be the new normal in the era of novel coronavirus epidemics. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1292–1295. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qiu J. Covert coronavirus infections could be seeding new outbreaks. Nature. 2020 Mar 20 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00822-x. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]