To the Editor: During the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, many aspects of dermatology resident education have been converted to an online format.1 Dermatopathology, comprising up to 30% of the training curriculum,2 already has a foothold in virtual learning, and virtual microscopy will completely replace glass slide microscopy on the dermatology board examination. Many departments, including ours, have curated virtual slide libraries to supplement education. In addition, the American Society of Dermatopathology has provided a list of freely accessible virtual slide libraries, lectures, and textbook-related content for self-study3 (https://www.asdp.org/about-asdp/covid-19-resources/).

Nevertheless, optimal dermatopathology education includes faculty interaction. With social distancing likely to remain in place for an extended period, instruction at a multiheaded microscope is not feasible. At our institution, we have combined video conferencing (eg, Webex or Zoom) with either glass slide microscopy or virtual microscopy for weekly didactics, review sessions, or routine sign-out (Fig 1 ). When the dermatopathologist shares the contents of the computer screen, the multiheaded microscope is simulated as residents view the same image without issues of focus, lighting, or available scope heads. Residents are able to participate either through speaking or the chat function. Questions posed through the chat function are reviewed periodically and read aloud before answers are given. These live slide sessions can be recorded for playback. However, the quality of the experience partly depends on a robust technical infrastructure, which includes hardware, systems and application software, and data network and storage.

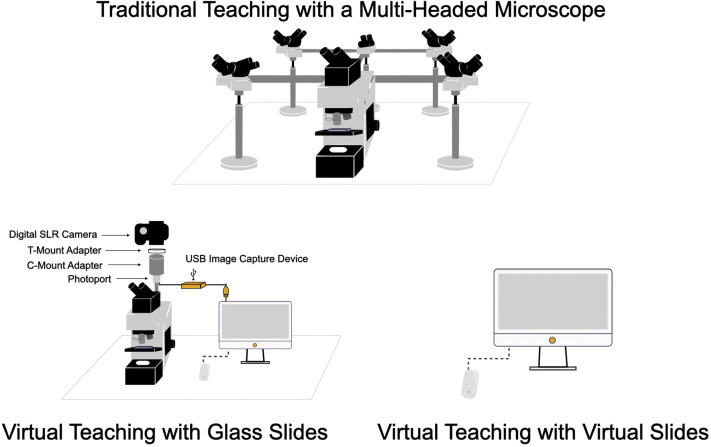

Fig 1.

Virtual simulation of the multiheaded microscope for teaching. SLR, Single-lens reflex; USB, universal serial bus.

For projecting glass slide microscopy, a digital single-lens reflex (SLR) camera can be attached to a trinocular microscope through T-mount or C-mount adapters that are specific to the equipment brand. Images are transferred to a computer via a USB image-capture device (Table I ). This approach is most suitable for teaching during routine sign-out or didactics with unknown glass slides. For virtual slides, our current platform is Aperio ImageScope, a whole-slide viewer that allows image rotation, magnification changes, and annotations. As opposed to static images with preselected relevant features, residents develop their diagnostic skills by searching the whole slide before progressing to targeted detection approaches4 during self-study. Features specific to ImageScope include fixed rather than continuous magnification and fixed-angle rotation instead of free manipulation, which some platforms allow, such as Leica's WebViewer. Last, multiple cases can be displayed simultaneously by window tiling, with the option of zoom synchronization. The ability to compare and contrast cases is critical to address areas of diagnostic confusion.

Table I.

Approximate costs for virtual projection of glass slides

| Equipment | Price, approximate, $ |

|---|---|

| Digital SLR camera | 400-2000 |

| T-mount adapter | 500 |

| C-mount adapter | 800 |

| Trinocular microscope head | 3500 |

| USB image capture device | 350 |

SLR, Single-lens reflex; USB, universal serial bus.

For dermatopathologists concerned about the technologic challenges of virtual microscopy, those participating in a virtual microscopy educational workshop rated the ease of navigation of virtual microscopy higher than that of glass slide microscopy.5 Educators should also be mindful of the limitations of remote teaching, such as delayed responses to digital communications or loss of nonverbal feedback, which is another important component of learning. Anecdotal and solicited feedback from our residents has provided iterative optimization of our virtual approach and has been overwhelmingly positive.

In this uncertain time, we have observed the resourcefulness of our colleagues in educating our trainees. We hope our experience will similarly offer a framework from which residents can learn dermatopathology.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Oldenburg R., Marsch A. Optimizing teledermatology visits for dermatology resident education during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(6):e229. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hinshaw M., Hsu P., Lee L.Y., Stratman E. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The American Society of Dermatopathology COVID-19 resources. https://www.asdp.org/about-asdp/covid-19-resources/ Available at:

- 4.Shahriari N., Grant-Kels J., Murphy M.J. Dermatopathology education in the era of modern technology. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44:763–771. doi: 10.1111/cup.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brick K.E., Comfere N.I., Broeren M.D., Gibson L.E., Wieland C.N. The application of virtual microscopy in a dermatopathology educational setting: assessment of attitudes among dermatopathologists. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:224–227. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]