Abstract

BACKGROUND

Heart failure (HF) hospitalization places patients at increased short-term risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE). Long-term risk for VTE associated with incident HF, HF subtypes, or structural heart disease is unknown.

OBJECTIVES

In the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) cohort, VTE risk associated with incident HF, HF subtypes, and abnormal echocardiographic measures in the absence of clinical HF was assessed.

METHODS

During follow-up, ARIC identified incident HF and subcategorized HF with preserved ejection fraction or reduced ejection fraction. At the fifth clinical examination, echocardiography was performed. Physicians adjudicated incident VTE using hospital records. Adjusted Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the association between HF or echocardiographic exposures and VTE.

RESULTS

Over a mean of 22 years in 13,728 subjects, of whom 2,696 (20%) developed incident HF, 729 subsequent VTE events were identified. HF was associated with increased long-term risk for VTE (adjusted hazard ratio: 3.13; 95% confidence interval: 2.58 to 3.80). In 7,588 subjects followed for a mean of 10 years, the risk for VTE was similar for HF with preserved ejection fraction (adjusted hazard ratio: 4.71; 95% CI: 2.94 to 7.52) and HF with reduced ejection fraction (adjusted hazard ratio: 5.53; 95% confidence interval: 3.42 to 8.94). In 5,438 subjects without HF followed for a mean of 3.5 years, left ventricular relative wall thickness and mean left ventricular wall thickness were independent predictors of VTE.

CONCLUSIONS

In this prospective population-based study, incident hospitalized HF (including both heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and reduced ejection fraction), as well as echocardiographic indicators of left ventricular remodeling, were associated with greatly increased risk for VTE, which persisted through long-term follow-up. Evidence-based strategies to prevent long-term VTE in patients with HF, beyond time of hospitalization, are needed.

Keywords: deep venous thrombosis, echocardiography, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, venous thromboembolism

Heart failure (HF) is an increasingly prevalent condition, with an estimated 6 million patients with HF in the United States (1). About one-half of incident HF hospitalizations are characterized as HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and the other one-half as HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (1). HF is characterized by a prothrombotic state, which not only increases the risk for cardioembolic events and ischemic stroke (2) but also increases the risk for deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), which together constitute venous thromboembolism (VTE) (3,4). Lifetime risk for VTE is 8% (5), and overall, the number of hospitalizations has risen since 2005 (1). About one-half of incident VTE events are considered “provoked” (6), with VTE incidence in patients with acute decompensated HF ranging from 4% to 26% in retrospective analyses (3). Several clinical trials have demonstrated that the risk for VTE in patients with HF hospitalization can be reduced with anticoagulation (7,8), which is supported by the American College of Chest Physicians (9) and American Society of Hematology (10) guidelines advocating prophylaxis in acutely ill patients with HF. However, prophylactic anticoagulation is currently not recommended beyond hospital discharge (10).

A large systematic meta-analysis of 46 cohort studies recently reported a 1.5-fold increased risk for VTE associated with HF hospitalization. However, the majority of included studies were retrospective cohorts and included subjects with chronic, prevalent HF as well as those on thromboprophylaxis (11). There was considerable heterogeneity among the included studies and therefore the potential for non-hospitalization-based confounders to exist. There is an ongoing need for a large, prospective study to define the risk for VTE independently associated with incident HF as well as HF subtype.

We previously found that N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide concentration was positively associated with incident VTE in ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study participants without histories of clinical HF (12). It can therefore be hypothesized that impairments in cardiac structure and function in the absence of acute hospitalization with clinical HF may also be a contributing factor to venous thrombogenesis.

Using the ARIC cohort, we aimed to assess the short- and long-term VTE risk associated with: 1) incident HF (overall); 2) HF subtype (HFpEF vs. HFrEF); and 3) abnormal echocardiographic measures in the absence of clinical HF.

METHODS

STUDY SAMPLE AND DESIGN

ARIC (13,14) enrolled 15,792 predominantly black or white men and women 45 to 64 years of age at baseline from 1987 through 1989. ARIC performed subsequent examinations from 1990 through 1992 (visit 2), 1993 through 1995 (visit 3), 1996 through 1998 (visit 4), 2011 through 2013 (visit 5), and 2016 and 2017 (visit 6), as well as annual or semiannual telephone contact. The institutional review committee at each study center approved the methods, and ARIC staff members obtained informed participant consent.

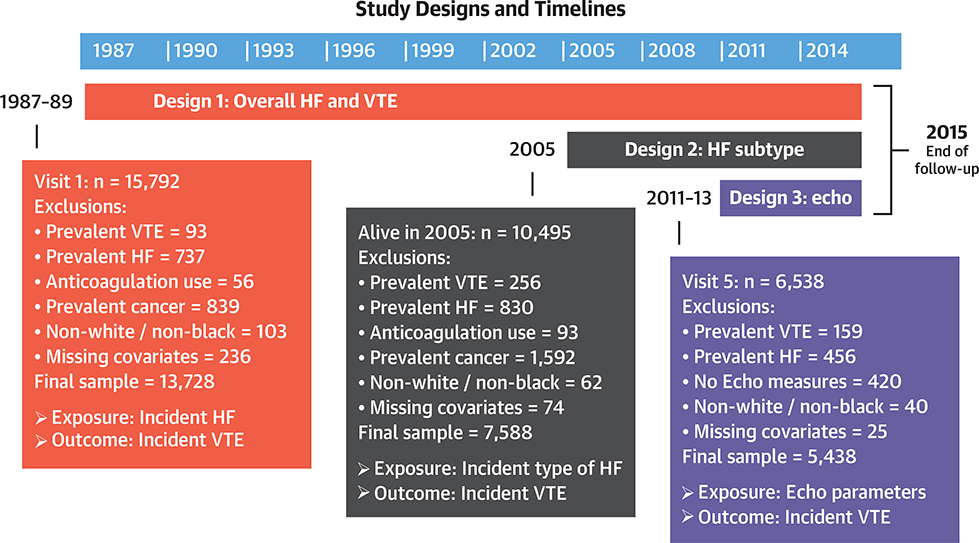

For this report, we prospectively examined both HF, as a time-dependent exposure, and echocardiographic parameters in relation to incident VTE during 3 follow-up periods (Figure 1). The 3 follow-up periods and designs were: 1) incident hospitalized HF on the basis of hospital discharge codes, occurring from baseline (1987 to 1989) through 2015, in relation to incident VTE from baseline through 2015 (overall design); 2) incident hospitalized decompensated HF (and HF phenotype) validated by ARIC criteria, occurring from 2005 through 2015, in relation to incident VTE from 2005 through 2015 (HF subtype design); and 3) echocardiographic parameters from ARIC visit 5 (2011 to 2013) in relation to incident VTE from 2011 through 2015 (echocardiography design). Adjustment variables came from baseline for design 1, from visit 4 for design 2, and from visit 5 for design 3. Note that the 3 designs have some overlapping years, exposures, and outcomes but successively added more specificity to the HF definition.

FIGURE 1. HF and VTE Prospective Study Design and Exclusion Criteria From the ARIC Cohort.

Timeline, exclusion criteria, and sample size information for the 3 designs used in this analysis. ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities; Echo = echocardiography; HF = heart failure; VTE = venous thromboembolism.

As shown in Figure 1, for designs 1 and 2, we excluded participants with prevalent VTE, prevalent HF, prevalent anticoagulant agent use, and prevalent cancer; nonwhite participants and nonblack participants at the Minnesota and Maryland centers (because of small numbers); and those missing covariates. Design 3 had similar exclusion criteria, except that we included only those with echocardiographic measures at visit 5 and in a sensitivity analysis excluded those with prevalent cancer by visit 5 and prevalent anticoagulant agent use.

IDENTIFICATION OF INCIDENT VTE

In the telephone contacts (yearly prior to 2012, twice yearly thereafter), ARIC staff members asked about all hospitalizations in the previous year and recorded the International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision- Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes for all discharge diagnoses. Staff members copied selected hospital record material for VTE validation through 2015. To validate VTE events, 2 physicians reviewed the records using standardized criteria (15), requiring positive imaging test results for diagnosis of DVT and PE. We previously published the VTE validation rates for various ICD-9-CM codes for the first years of follow-up (6). The reviewers subclassified VTEs as unprovoked (no obvious cause) or provoked (associated with cancer, major trauma, major surgery, or marked immobility [coma, paralysis, orthopedicinduced limitation, bed rest] in the prior 90 days). For this study, we restricted DVTs to those in the lower extremity or vena cava, because upper extremity DVTs were relatively few and almost always the result of indwelling venous catheters.

MEASUREMENT OF HF AND ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC PARAMETERS

At baseline, we defined prevalent HF, for exclusion, as an affirmative response to “Were any of the medications you took during the last 2 weeks for heart failure?” or as stage 3 or “manifest” HF, on the basis of symptoms and signs, using Gothenburg criteria (15). Prior to 2005, ARIC did not collect record material other than discharge codes for incident HF hospitalizations. We therefore defined incident hospitalized HF by discharge codes, for 1987 through 2015, as an ICD-9-CM code 428.x in any position (16). After 2005, ARIC staff members abstracted a broad range of hospital records for potential HF events, and ARIC physicians classified incident hospitalized decompensated HF using published criteria (17). Reviewing physicians also classified HF into 3 types: HFpEF, HFrEF, and undetermined.

At visit 5, ARIC also performed standardized echocardiographic examinations, including 2-dimensional, Doppler and 3-dimensional evaluation, as previously reported (18). Because by visit 5 there was substantial cohort attrition due to death or nonparticipation, the Online Appendix includes a comparison of those who participated in visit 5 with those who did not. As described in more detail in the Online Appendix, at all clinic visits, ARIC measured other potential VTE risk factors to allow us to adjust for them as possible confounding variables.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We calculated baseline characteristics by incident HF status as well as crude incidence rates of VTE, PE, DVT, unprovoked VTE, and provoked VTE per 1,000 person-years. We defined person-years from the starting point until VTE, death, loss to follow-up, or administrative censoring on December 31, 2015, whichever occurred first. We estimated event-free survival probability by HF status using the Kaplan-Meier method and the STS command in Stata (StataCorp, College Station, Texas). Participants contribute time to the no HF group, and if they develop HF, they start over at time 0 contributing time to the HF group. Within designs 1 and 2, we used Cox models to compute hazard ratios (HRs) associating time-dependent HF with incident VTE. A VTE event resulted in the end of follow-up time, and thus any HF occurrence after VTE is not relevant in this analysis. Within design 3, we computed HRs associating echocardiographic parameters in subjects free of HF with VTE; incident HF after echocardiography was ignored, as it would be a mediator. We adjusted the Cox models for age (continuous), race, sex, body mass index (continuous), education (high school education or less vs. high school completion or more), hypertension, and aspirin use. Total cholesterol, chronic kidney disease, diabetes, cigarette smoking status, coronary heart disease, stroke, and claudication did not confound, so we excluded them from the final model. For all 3 designs, the proportional hazards assumption was checked using Schoenfield residuals and by inspection of log(−log [survival]) curves, and there was no evidence of violations. We performed the following sensitivity analyses: 1) for design 1, we repeated analyses excluding VTE events within 30, 90, and 180 days after HF hospitalization; 2) for both designs 1 and 2, we repeated analyses adjusted for the total number of hospitalizations per year during follow-up (which may be a confounding variable) as a time-dependent analysis; and 3) for design 3, additional adjustment was made for chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation (AF). We used SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) and STATA version 14.0.

RESULTS

DESIGN 1: OVERALL INCIDENT HF AND VTE, ARIC 1987 TO 2015

Incident HF occurred in 2,696 of the 13,728 participants (19.6%) included in design 1 (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics by incident HF status are presented in Table 1. In general, participants with incident HF were more likely than those with no HF to be older (mean age 56.1 vs. 53.5 years), male (50% vs. 45%), and black (33% vs. 24%); to have a lower education level (35% vs. 20%); and to have more cardiovascular comorbidities, such as hypertension (49% vs. 28%), diabetes (23% vs. 8%), and coronary artery disease (10% vs. 3%). As detailed in Table 2, over a mean of 22 ± 7 years of follow-up, there were 729 VTE events. Incident HF was associated with more than a 3-fold higher risk for subsequent incident total VTE (HF vs. no HF: incidence rate: 11.8 vs. 2.3 per 1,000 person-years; adjusted HR: 3.13; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.58 to 3.80). Incident HF was a 2-fold or greater risk factor for all VTE subgroups, both PE (adjusted HR: 2.57; 95% CI: 1.95 to 3.39) and DVT (adjusted HR: 3.90; 95% CI: 2.96 to 5.13), as well as provoked (adjusted HR: 2.26; 95% CI: 1.60 to 3.19) and unprovoked VTE events (adjusted HR: 3.72; 95% CI: 2.94 to 4.72). A significant interaction by race was present, with a 4.4-fold increased risk for VTE with HF in blacks compared with a 2.4-fold increased risk in whites (p = 0.0005). The interaction was also present for both PE and DVT (Online Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics (1987 to 1989) of Patients With Incident HF Hospitalization (ARIC, 1987 to 2015)

| No HF Hospitalization (n = 11,032) | HF Hospitalization (n = 2,696) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 53.5 ± 6 | 56.1 ± 5 |

| Men | 4,992 (45) | 1,351 (50) |

| Black | 2,681 (24) | 886 (33) |

| Education high school or less | 2,209 (20) | 946 (35) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.1 ± 5 | 29.2 ± 6 |

| Hypertension | 3,120 (28) | 1,332 (49) |

| Diabetes | 864 (8) | 624 (23) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 213.8 ± 41 | 218.9 ± 44 |

| Hyperlipidemia* | 6,750 (61) | 1,764 (65) |

| Ever smoker | 6,168 (56) | 1,794 (67) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 103.2 ± 15 | 101 ± 18 |

| CKD | 77 (0.7) | 67(2) |

| Aspirin use | 4,970 (45) | 1,279 (47) |

| Prevalent coronary heart disease | 276 (3) | 262 (10) |

| Prevalent stroke | 143 (1) | 68 (3) |

| Atrial fibrillation on ECG | 10 (1) | 7 (0.3) |

| History of claudication | 366 (3) | 147 (5) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl or use of lipid medications.

ARIC = Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities; BMI = body mass index; CKD = chronic kidney disease (defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m2); ECG = electrocardiography; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; HF = heart failure.

TABLE 2.

Adjusted Risk for Incident VTE and VTE Subtype by HF Hospitalization in ARIC (1987 to 2015)

| No HF (n = 11,032) | HF Hospitalization (n = 2,696) | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of VTE events | 584 | 145 |

| Person-years | 256,055 | 12,277 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 2.28 (2.10–2.47) | 11.8 (10.0–13.9) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 3.13 (2.58–3.80) |

| Number of PE events | 314 | 70 |

| Person-years | 256,055 | 12,277 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 1.23 (1.10–1.37) | 5.70 (4.48–7.16) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 2.57 (1.95–3.39) |

| Number of DVT events | 270 | 75 |

| Person-years | 256,055 | 12,277 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 1.05 (0.93–1.19) | 6.11 (4.84–7.61) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 3.90 (2.96–5.13) |

| Number of unprovoked VTE events | 241 | 43 |

| Person-years | 256,055 | 12,277 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) | 3.50 (2.57–4.67) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 2.26 (1.60–3.19) |

| Number of provoked VTE events | 343 | 102 |

| Person-years | 256,055 | 12,277 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 1.34 (1.20–1.49) | 8.31 (6.81–10.0) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 3.72 (2.94–4.72) |

Unadjusted incidence rate is per 1,000 person-years.

Model is adjusted for baseline age (continuous), race, sex, body mass index (continuous), education (more than high school vs. not), hypertension, and aspirin use.

CI = confidence interval; DVT = deep venous thrombosis; PE = pulmonary embolism; VTE = venous thromboembolism; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Although the increased risk for VTE was greatest within the first month following initial HF hospitalization, the increased risk continued through long-term follow-up (Figure 2). In a sensitivity analysis, during which VTE events were excluded that occurred within 30, 90, and 180 days of hospitalization, incident HF was still associated with an increased risk for VTE (Table 3). Similarly, after additional adjustment in the multivariate model for the number of hospitalizations per year during follow-up, incident HF was still associated with increased risk for VTE (adjusted HR: 2.68; 95% CI: 2.18 to 3.28).

FIGURE 2. Kaplan-Meier Curve Analysis for Incident VTE by HF Status (ARIC, 1987 to 2105).

Event-free survival probability by HF status was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the STS command in Stata. Participants contribute time to the no HF group, and if they develop incident HF, they start over at time 0 contributing time to the HF group. The number at risk for developing incident VTE at the start of each time period is listed below the figure, stratified by HF status. Those with HF have a higher risk for developing VTE compared with those without HF. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

TABLE 3.

Risk for VTE With Incident HF After Exclusion of VTE Events Within 30, 90, and 180 Days After HF Hospitalization (ARIC, 1987 to 2015)

| No HF | HF Hospitalization | |

|---|---|---|

| No VTE within 30 days (excludes 43 events) | ||

| Number of VTE events | 584 | 102 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 2.17 (1.74–2.71) |

| No VTE within 90 days (excludes 58 events) | ||

| Number of VTE events | 584 | 87 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.84 (1.45–2.33) |

| No VTE within 180 days (excludes 65 events) | ||

| Number of VTE events | 584 | 80 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 1.68 (1.32–2.15) |

DESIGN 2: HF SUBTYPES AND VTE, ARIC 2005 TO 2015

Incident HF occurred in 1,005 of the 7,588 participants (15.3%) included in design 2 (Figure 1), during which HF subtype definitions were established and assessed. Of these, 278 (27.7%) were categorized as HFpEF, 275 (27.4%) as HFrEF, and 452 (45.0%) as undetermined HF type. As presented in Table 4, those with HFrEF compared with HFpEF more often were men (62% vs. 31%) and had histories of coronary artery disease (17% vs. 7%) and smoking (69% vs. 62%). Over a mean of 9.7 ± 2.6 years, there were 262 incident VTE events (Table 5). Rates of VTE in those with HF were 21.8 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 16.9 to 27.6) versus 3.04 per 1,000 person-years (95% CI: 2.64 to 3.49) for those without HF. Compared with no HF, HFpEF (adjusted HR: 4.71; 95% CI: 2.94 to 7.52), HFrEF (adjusted HR: 5.53; 95% CI: 3.42 to 8.94), and undetermined incident HF (adjusted HR: 4.09; 95% CI: 2.60 to 6.44) all demonstrated similar VTE incident rates. Risk remained elevated for all HF subtypes regardless of VTE subtype (PE, DVT, provoked VTE, and unprovoked VTE) (Table 5).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics (1996 to 1998) of Patients by Incident HF Subtype (ARIC, 2005 to 2015)

| No HF (n = 6,583) | Any HF (n = 1,005) | HFpEF (n = 278) | HFrEF (n = 275) | HF Type (n = 452) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | 61.6 ± 5.0 | 64.2 ± 5.0 | 64.5 ± 5.4 | 64.4 ± 5.5 | 64.0 ± 5.4 |

| Men | 2,693 (41) | 447 (44) | 87 (31) | 170 (62) | 190 (42) |

| Black | 1,397 (21) | 283 (28) | 80 (29) | 76 (28) | 127 (28) |

| Education high school or less | 1,015 (15) | 276 (27) | 80 (29) | 84 (31) | 112 (25) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.4 ± 5.0 | 29.7 ± 6.0 | 30.2 ± 7.0 | 28.9 ± 5.0 | 29.8 ± 6.0 |

| Hypertension | 2,662 (40) | 600 (60) | 168 (60) | 164 (60) | 268 (59) |

| Diabetes | 779 (12) | 260 (26) | 79 (28) | 76 (28) | 105 (23) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 202.3 ± 36.0 | 200.7 ± 38.0 | 205.5 ± 40.0 | 195.0 ± 36.0 | 201.3 ± 38.0 |

| Hyperlipidemia* | 3,713 (56) | 573 (57) | 177 (64) | 140 (51) | 256 (57) |

| Ever smoker | 3,586 (54) | 659 (66) | 172 (62) | 190 (69) | 297 (66) |

| eGFR, ml/min/1.73 m2 | 88.4 ± 15.0 | 83.6 ± 18.0 | 82.9 ± 18.0 | 83.2 ± 19.0 | 84.4 ± 18.0 |

| CKD | 247 (4) | 91 (9) | 21 (8) | 31 (11) | 39(9) |

| Aspirin use | 3,566 (54) | 591 (59) | 158 (57) | 154 (56) | 279 (62) |

| Prevalent coronary heart disease | 278 (4) | 120 (12) | 20 (7) | 48 (17) | 52 (12) |

| Prevalent stroke | 71 (1) | 33 (3) | 10 (4) | 8 (3) | 15 (3) |

| Prevalent atrial fibrillation | 166 (3) | 86 (9) | 30 (11) | 21 (8) | 35 (8) |

| History of claudication | 196 (3) | 62 (6) | 16 (6) | 19(7) | 27 (6) |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Total cholesterol ≥200 mg/dl or use of lipid medications.

HFpEF = HF with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = HF with reduced ejection fraction; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

TABLE 5.

Crude Incidence and Adjusted Risk for VTE bv Incident HF Subtype (ARIC, 2005 to 2015)

| No HF (n = 6,583) | Any HF (n = 1,005) | HFpEF (n = 278) | HFrEF (n = 275) | Undetermined HF Type (n = 452) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of VTE events | 199 | 63 | 21 | 19 | 23 |

| Person-years | 65,451 | 2,895 | 908 | 778 | 1,208 |

| Incidence rate (95% CI)* | 3.04 (2.64–3.49) | 21.8 (16.9–27.6) | 23.1 (14.7–34.7) | 24.4 (15.2–37.4) | 19.0 (12.4–28.1) |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 5.15 (3.80–6.98) | 4.71 (2.94–7.52) | 5.53 (3.42–8.94) | 4.09 (2.60–6.44) |

| Race interaction, p value | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.86 | 0.55 | |

| Number of PE events | 135 | 36 | 12 | 7 | 17 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 4.41 (2.98–6.54) | 4.09 (2.22–7.55) | 3.12 (1.45–6.74) | 4.55 (2.67–7.75) |

| Number of DVT events | 64 | 27 | 9 | 12 | 6 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 6.66 (4.11–10.81) | 5.91 (2.84–12.3) | 10.1 (5.34–19.0) | 3.21 (1.34–7.66) |

| Number of unprovoked VTE events | 87 | 26 | 8 | 7 | 11 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 4.77 (2.99–7.62) | 4.01 (1.89–8.50) | 4.66 (2.13–10.2) | 4.59 (2.37–8.90) |

| Number of provoked VTE events | 112 | 37 | 13 | 12 | 12 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1.00 (reference) | 5.53 (3.71–8.25) | 5.39 (2.95–9.82) | 6.44 (3.49–11.9) | 3.74 (2.00–7.00) |

For design 2, there was a significant difference in incident VTE between HF and no HF over the entire follow-up period (log-rank p < 0.0001), but no difference in incident VTE risk existed among HF subtypes (HF subtype 3-way log-rank p = 0.66) (Figure 3). For design 2, there was no significant race interaction for incident VTE for overall HF (p = 0.36), HFpEF (p = 0.49), or HFrEF (p = 0.86). Adjusting the final model for baseline N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide did not greatly change the risk for VTE (HFpEF: adjusted HR: 4.77; 95% CI: 2.97 to 7.66; HFrEF: adjusted HR: 5.52; 95% CI: 3.41 to 8.94). In sensitivity analyses, incident HF was still associated with an increased risk for VTE (adjusted HR: 2.48; 95% CI: 1.72 to 3.58) after adjustment for number of hospitalizations per year during follow-up.

FIGURE 3. Kaplan-Meier Analysis for Incident VTE by Incident HF Subtype (ARIC, 2005 to 2015).

Event-free survival probability by HF subtype status was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the STS command in Stata. Participants contribute time to the no HF group, and if they develop incident HF, they start over at time 0 contributing time to a HF subtype group. The number at risk for developing incident VTE at the start of each time period is listed below the figure, stratified by HF subtype status. Those with HF have a higher risk for developing VTE compared with those without HF. The curves for HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and HF with unknown ejection fraction (EF) are very similar. Abbreviations as in Figure 1.

DESIGN 3: ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS AND VTE, ARIC 2011 TO 2015

After exclusion criteria, 5,438 participants without HF were included in the echocardiographic design 3 analysis (Figure 1). There were 86 incident VTE events over a mean follow-up time of 3.5 ± 0.7 years. Baseline clinical characteristics of participants without baseline HF are presented according to incident VTE status in Online Table 2. In general, those with incident VTE versus those without were more often black (29% vs. 21%); were of lower education levels (22% vs. 12%); and had more prevalent hypertension (80% vs. 72%), chronic kidney disease (43% vs. 33%), coronary heart disease (16% vs. 13%), and AF (14% vs. 6%). Baseline echocardiographic measures by incident VTE status are presented in Table 6. In unadjusted univariate analyses, those who developed VTE had at baseline greater left ventricular (LV) relative wall thickness (0.46 vs. 0.43; p = 0.03), mean LV wall thickness (1.03 cm vs. 0.98 cm; p = 0.01), and left atrial (LA) volume index (27.9 ml/m2 vs. 25.5 ml/m2; p = 0.008) and borderline lower longitudinal strain values (17.7% vs. 18.1%; p = 0.05). In adjusted model 1 (Table 7), these factors remained independent predictors (per SD increase) of incident VTE with the addition of LV mass index. After additional adjustment for chronic kidney disease and AF, LV relative wall thickness (adjusted HR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.44; p = 0.002) and mean LV wall thickness (adjusted HR: 1.32; 95% CI: 1.10 to 1.59; p = 0.003) remained predictors of incident VTE in the absence of baseline HF.

TABLE 6.

Echocardiographic Measures by VTE Status in Participants Without Baseline Heart Failure (ARIC, 2011 to 2015)

| Number Out of 5,438 With Measure | No Incident VTE (n = 5,352) | Incident VTE (n = 86) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV diastolic diameter, cm | 5,397 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 0.58 |

| LVEF, % | 5,271 | 65.6 ± 6.1 | 64.7 ± 6.1 | 0.15 |

| LVEF category (<59% M, <57% W) | 5,271 | 431 (8) | 11 (13) | 0.11 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | 5,396 | 78.3 ± 18.8 | 82.5 ± 22.1 | 0.09 |

| LV relative wall thickness | 5,397 | 0.43 ± 0.1 | 0.46 ± 0.1 | 0.03 |

| Mean LV wall thickness, cm | 5,410 | 0.98 ± 0.1 | 1.03 ± 0.2 | 0.01 |

| RV diastolic area, cm2 | 4,969 | 19.5 ± 5.2 | 19.2 ± 4.7 | 0.55 |

| RV systolic area, cm2 | 4,969 | 9.3 ± 2.9 | 9.0 ± 2.5 | 0.30 |

| RV fractional area change | 4,969 | 0.52 ± 0.1 | 0.53 ± 0.1 | 0.69 |

| LAVI, ml/m2 | 5,385 | 25.5 ± 8.4 | 27.9 ± 9.2 | 0.008 |

| LAVI category (>31 ml/m2 M, >30 ml/m2 W) | 5,385 | 1,154 (22) | 26 (31) | 0.05 |

| LAD, cm | 5,411 | 3.52 ± 0.5 | 3.58 ± 0.6 | 0.25 |

| LAD category (>4.0 cm M, >3.7 cm W) | 5,411 | 1,314 (25) | 30 (35) | 0.02 |

| E/A ratio | 5,261 | 0.86 ± 0.3 | 0.87 ± 0.4 | 0.73 |

| E/E′ lateral ratio, cm/s | 5,408 | 10.1 ± 3.8 | 10.8 ± 4.7 | 0.17 |

| Lateral e/e′ ratio category (>11.5 M, >13.3 W) | 5,408 | 1,041 (20) | 15 (18) | 0.66 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity, cm/s | 3,141 | 2.38 ± 0.3 | 2.42 ± 0.3 | 0.35 |

| Peak RV-RA gradient, mm Hg | 3,141 | 23.0 ± 5.7 | 23.8 ± 6.5 | 0.32 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, Wood units | 3,128 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | 0.42 |

| Pulmonary HTN, moderate or greater | 5,438 | 29 (0.54) | 1 (1.2) | 0.53 |

| Septal e′, cm/s | 5,422 | 5.71 ± 1.5 | 5.48 ± 1.4 | 0.16 |

| Septal E/e′, cm/s | 5,262 | 9.44 ± 1.9 | 9.24 ± 2.1 | 0.33 |

| Longitudinal strain, % (absolute value) | 5,099 | 18.1 ± 2.4 | 17.6 ± 2.7 | 0.05 |

| Circumferential strain, % (absolute value) | 4,012 | 28.0 ± 3.7 | 26.8 ± 4.7 | 0.07 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%), unless otherwise indicated.

TABLE 7.

HRs of VTE by Echocardiographie Measure in Participants Without Baseline HF (ARIC, 2011 to 2015)

| Model 1 |

Model 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Echocardiographic Measure | HR (95% CI) | p Value | HR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| LV diastolic diameter (0.49 cm) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.98 (0.78–1.25) | 0.89 | 0.96 (0.76–1.21) | 0.72 |

| LVEF (6.1%) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.83 (0.68–1.02) | 0.08 | 0.87 (0.71–1.05) | 0.15 |

| LVEF category (<59% M, <57% W) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.83 (0.95–3.53) | 0.07 | 1.66 (0.85–3.23) | 0.14 |

| LV mass index (18.7 g/m2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.25 (1.03–1.51) | 0.03 | 1.21 (1.00–1.48) | 0.05 |

| LV relative wall thickness (0.07 cm) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.26 (1.10–1.45) | 0.001 | 1.25 (1.09–1.44) | 0.002 |

| Mean LV wall thickness (0.13 cm) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.35 (1.13–1.62) | 0.001 | 1.32 (1.10–1.59) | 0.003 |

| RV diastolic area (5.2 cm2) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.89 (0.68–1.15) | 0.37 | 0.87 (0.70–1.13) | 0.30 |

| RV systolic area (2.9 cm2) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.84 (0.64–1.11) | 0.22 | 0.81 (0.62–1.07) | 0.14 |

| RV fractional area change (0.08) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.06 (0.84–1.33) | 0.65 | 1.08 (0.86–1.36) | 0.52 |

| LAVI (8.4 ml/m2) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.17 (1.03–1.32) | 0.02 | 1.13 (0.97–1.32) | 0.12 |

| LAVI category (>31 ml/m2 M, >30 ml/m2 W) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.47 (0.92–2.35) | 0.11 | 1.30 (0.81–2.11) | 0.28 |

| LAD (0.51 cm) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.21 (0.96–1.52) | 0.11 | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) | 0.34 |

| LAD category (>4.0 cm M, >3.7 cm W) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.70 (1.06–2.74) | 0.03 | 1.50 (0.92–2.44) | 0.10 |

| E/A ratio (0.28) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.11 (0.91–1.35) | 0.29 | 1.05 (0.87–1.27) | 0.62 |

| E/E′ lateral ratio (3.8 cm/s) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.14 (0.94–1.38) | 0.18 | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) | 0.19 |

| Lateral e/e′ ratio category (>11.5 M, >13.3 in W) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.85 (0.49–1.50) | 0.58 | 0.85 (0.48–1.50) | 0.58 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation velocity (0.28 cm/s) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.04 (0.80–1.34) | 0.77 | 1.02 (0.79–1.32) | 0.89 |

| Peak RV-RA gradient (5.7 mm Hg) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.04 (0.81–1.35) | 0.74 | 1.02 (0.79–1.32) | 0.86 |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance (0.42 Wood units) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.11 (0.87–1.43) | 0.40 | 1.05 (0.82–1.35) | 0.71 |

| Pulmonary HTN, moderate or greater | 1.00 (reference) | 1.87 (0.26–13.6) | 0.53 | 1.40 (0.19–10.2) | 0.74 |

| Septal e′ (1.5 cm/s) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.90 (0.72–1.13) | 0.37 | 0.88 (0.70–1.10) | 0.27 |

| Septal E/e′ (1.9 cm/s) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | 0.62 | 1.01 (0.81–1.26) | 0.92 |

| Longitudinal strain (2.4%) (absolute value) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.85 (0.69–1.05) | 0.13 | 0.89 (0.72–1.10) | 0.27 |

| Circumferential strain (3.7%) (absolute value) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.78 (0.62–0.99) | 0.04 | 0.81 (0.64–1.02) | 0.08 |

Model 1 adjusted for age (continuous), race, sex, body mass index (continuous), education (more than high school vs. not), hypertension, and aspirin use; model 2 adjusted for model 1 plus chronic kidney disease and atrial fibrillation. HRs for all continuous measures per 1 SD unit increase.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this ARIC report is the first long-term longitudinal prospective analysis of incident HF as a risk factor for incident VTE. Our findings demonstrated that incident HF hospitalization was associated with both short-term and long-term risk for VTE, independent of multiple VTE risk factors (Central Illustration). The increased VTE risk emerged shortly after incident HF hospitalization, as might be expected, but was present even after removal of early hospital-related VTE events and adjustment for the number of subsequent hospitalizations. The risk posed by HF remained through a mean 22-year follow-up period regardless of VTE type (DVT, PE, and unprovoked and provoked VTE events). Interestingly, there was no discernable difference in risk between HFpEF and HFrEF. Even in those without clinical HF, early changes in LV wall thickness and concentricity detected by echocardiography were predictive of incident VTE. The consistency and strength of the associations across our 3 designs may suggest a causal relation between HF and VTE.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Incident Heart Failure and Risk for Venous Thromboembolism From the Longitudinal Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities Cohort.

(A) Incidence rate per 1,000 person-years of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and categories of VTE according to incident heart failure (HF) status. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) reflect final model adjusted for age (continuous), race, sex, body mass index (BMI) (continuous), education (more than high school vs. not), hypertension, and aspirin use. (B) Kaplan-Meier analysis for incident VTE by incident HF status (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities [ARIC], 1987 to 2015). (C) Crude incidence and adjusted risk for VTE by incident HF subtype (ARIC, 2005 to 2015). Adjusted HRs reflect final model adjusted for age (continuous), race, sex, BMI (continuous), education (more than high school vs. not), hypertension, and aspirin use. (D) Kaplan-Meier analysis for incident VTE by incident HF subtype (ARIC, 2005 to 2015). DVT = deep venous thrombosis; EF = ejection fraction; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; PE = pulmonary embolism.

HF HOSPITALIZATION AND RISK FOR VTE

An estimated 11% of all acute hospitalizations are due to HF (19), which is expected to increase given current demographic trends of aging. A PE event during an HF hospitalization has been associated with increased mortality or HF rehospitalization (20). The actual risk for VTE in HF both in the short term and long term has been difficult to elucidate, because of the retrospective nature of many existing epidemiological studies (3,11), which imposes possible selection bias and confounding. Patients hospitalized for acute HF are at increased risk for short-term VTE because of prolonged immobilization and hypercoagulability from acute medical illness, and the use of anticoagulant agents in this patient population is known to reduce short-term incident VTE without a major risk for bleeding (9,10,21). Present guidelines recommend against long-term VTE prophylaxis after discharge from an HF hospitalization (10) because of lack of prospective data on the long-term risk of VTE in HF. The APEX (Acute Medically Ill VTE Prevention With Extended Duration Betrixaban Study) trial analyzed extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban versus placebo in patients with a hospitalization for acute medical illness. The primary efficacy outcome was not met in the trial cohort of patients enriched for high risk for VTE by D-dimer level (relative risk: 0.81; 95% CI: 0.65 to 1.00; p = 0.054). However, in the overall trial cohort, of which close to 50% of patients had acute decompensated HF, there was a 24% relative risk reduction with extended thromboprophylaxis (p = 0.006), a result that was considered exploratory. There was no heterogeneity in efficacy in those with HF (relative risk: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.62 to 1.16; p for interaction = 0.72), although the trial was not powered for this subgroup analysis (22). Although APEX was considered a trial of extended thromboprophylaxis, total follow-up duration was up to only 42 days. Our study demonstrated that even after removing VTE events that occurred relatively soon after the HF hospitalization (i.e., excluding VTE events in the first 30, 90, and 180 days), there was still a near 2-fold increased risk for incident VTE among those with HF, and the incidence of unprovoked VTE associated with HF was 3.5 per 1,000 person-years versus 0.94 per 1,000 person-years in those without.

HF SUBTYPES AND THROMBOEMBOLIC RISK

To the best of our knowledge, this large prospective study is the first to determine the incidence of VTE on the basis of subtype of incident hospitalized HF. Proposed mechanisms for thromboembolism in HF are well described and include blood stasis from impaired contractility, increased plasma viscosity, platelet and coagulation system activation, and endothelial dysfunction (2). Historically, clinical data from epidemiological studies on VTE risk in HF have not differentiated between systolic and diastolic LV dysfunction, and large randomized trials of anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolic events in HF have excluded those with HFpEF (23–27). In cross-sectional analyses, systolic dysfunction (but not diastolic dysfunction) correlates with altered plasma fibrinogen, D-dimer, and von Willebrand factor (28). However, it has been hypothesized that altered blood flow hemodynamic parameters, such as those associated with increased ventricular stiffness and poor myocardial compliance, may precipitate thrombus formation independent of biomarker abnormalities (28). In our adjusted models, incident HFpEF hospitalization increased long-term VTE risk by nearly 5-fold. Given this large association, the increased risk for thrombogenesis associated with HFpEF, as well as the long-term strategies to attenuate this risk, warrant ongoing study.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHIC INDICATORS OF VTE RISK

Using one of the largest and most comprehensive echocardiographic datasets (18), this is the first study to evaluate imaging parameters associated with incident VTE in the absence of clinical HF. We tested the hypothesis that early abnormalities in myocardial compliance, independent of clinical comorbidities and before incident HF, may increase the risk for long-term venous thrombosis. One prior echocardiography study has demonstrated an association of E/e′ and e′ velocity with increased atrial thrombus risk in patients with nonvalvular AF (29). Our data show that greater mean LV wall thickness, relative wall thickness (a measure of LV concentricity), and LA volume index (a barometer of chronic LV filling pressure) were associated with greater risk for incident VTE, indicating that stage B HF (symptomatic LV remodeling) may be a risk factor for VTE. Given that the prevalence of stage B HF is estimated to be 4 times that of stages C and D HF combined (30), increased VTE awareness based on other risk factors may be warranted. Because AF and chronic kidney disease are known to be shared risk factors for VTE, concentric LV remodeling, and LA enlargement (29), we performed additional adjustment for these factors and found that LV relative wall thickness and mean wall thickness, but not the E/e′ ratio, e′ velocity, or LA volume index, remained predictors of venous thrombosis. This suggests a different pathophysiologic mechanism in venous thrombogenesis compared with that of LA appendage thrombus or systemic embolic events in AF, which warrants ongoing investigation.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

First, ARIC based incident HF on hospitalizations, because of the difficulty of obtaining outpatient HF diagnoses. We also used only discharge ICD-9-CM codes to define HF in design 1, whereas we were able to perform physician adjudication of HF in design 2. Reassuringly, the validity of hospital ICD-9-CM codes is high for HF in ARIC (17), so the effect of HF misclassification on HRs should be mitigated.

Second, our VTE validation failed to capture outpatient VTE, which has become increasingly more common in recent years. Yet restricting to hospitalized VTE was deemed acceptable because many ARIC VTEs occurred before outpatient treatment was widespread, ARIC participants are now elderly and are still likely mostly hospitalized when they develop VTE, and hospitalized VTE is likely to be captured well via ICD-9-CM codes but outpatient VTE less so (31,32).

Third, the number of VTE events for design 3 was small, and many statistical tests were performed; therefore, those results warrant replication.

Fourth, although there are many mechanisms by which HF could increase VTE, the observed association may not be causal. Patients with HF often have multiple comorbidities, and although we adjusted for measured VTE risk factors, follow-up was long, and there may be residual confounding from other risk factors or triggers of VTE that arose over time.

Last, incident VTE-related mortality was not assessed in this study. Although VTE at the time of a HF hospitalization increases the risk for mortality (20), the risk for death directly attributable to VTE in HF over longer term follow-up remains unknown.

CONCLUSIONS

In this large prospective population-based study, incident hospitalized HF was associated with a greatly increased risk for VTE, and the risk persisted in participants with HFpEF and HFrEF, over both short- and long-term follow-up. In the absence of clinical HF, greater LV relative wall thickness and mean wall thickness were also independently associated with increased VTE risk. Results may suggest a causal relationship between HF, including asymptomatic stage B HF, and VTE, well beyond the time of hospitalization, and further studies are warranted to further define this relationship.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE

Patients who have been hospitalized with HF and either reduced or preserved LV ejection or even with echocardiographic features of ventricular remodeling face an increased risk for developing VTE that persists through several decades of follow-up.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK

Further studies are needed to develop evidence-based strategies that reduce the risk for VTE in patients with HF well beyond the time of hospitalization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staff members and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute provided support for venous thromboembolism identification (R01 HL059367) and for the ARIC study (HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I, and HHSN268201700005I). The work for this paper was also supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants K08HL116792, R01HL135008, and R01HL143224 (to Dr. Shah). Roche Diagnostics provided funding and laboratory reagents for the N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide and TnT assays. Dr. Fanola has received consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Johnson and Johnson, Janssen, and Inari Medical. Dr. Shah has received research support from Novartis; and has received consulting fees from Philips Ultrasound and Bellerophon.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AF

atrial fibrillation

- CI

confidence interval

- DVT

deep venous thrombosis

- HF

heart failure

- HFpEF

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

- HFrEF

heart failure with reduced ejection fraction

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases-9th Revision-Clinical Modification

- LA

left atrial

- LV

left ventricular

- PE

pulmonary embolism

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics 2018 update. Circulation 2018;137:e67–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lip GYH, Gibbs CR. Does heart failure confer a hypercoagulable state? Virchow’s triad revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1424–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alikhan R, Spyropoulos AC. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism in cardiorespiratory and infectious disease. Am J Med 2008;121:935–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alikhan R, Cohen AT, Combe S, et al. Risk factors for venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with acute medical illness: analysis of the MEDENOX study. Arch Intern Med 2004;164: 963–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell EJ, Lutsey PL, Basu S, et al. Lifetime risk of venous thromboembolism in two cohort studies. Am J Med 2016;129:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cushman M, Tsai A, White RH, et al. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in two cohorts: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Am J Med 2004;1:19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen AT, Davidson BL, Gallus AS, et al. Efficacy and safety of fondaparinux for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in older acute medical patients: randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2006;332:325–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen AT, Turpie AG, Leizorovicz A, et al. Thromboprophylaxis with dalteparin in medical patients: which patients benefit? Vasc Med 2007; 12:123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012;141: e195S–226S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schünemann HJ, Cushman M, Burnett AE, et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prophylaxis for hospitalized and nonhospitalized medical patients. Blood Adv 2018;22:3198–225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang L, Wu Y, Lip GH, Yin P, Hu Y. Heart failure and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol 2016; 1:e30–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, Nambi V, et al. Troponin T, NT-pro BNP, and venous thromboembolism: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE). Vasc Med 2014;19:33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai AW, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors and venous thromboembolism incidence: the longitudinal investigation of thromboembolism etiology. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1182–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The ARIC Investigators. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eriksson H, Caidahl K, Larsson B, et al. Cardiac and pulmonary causes of dyspnoea- validation of a scoring test for clinical-epidemiological use: the Study of Men Born in 1913. Eur Heart J 1987;8:1007–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study). Am J Cardiol 2008;101: 1016–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Baggett C, et al. Classification of heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: a comparison of diagnostic criteria. Circ Heart Fail 2012;5:152–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah AM, Cheng S, Skali H, et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter echocardiographic study to assess the relationship between cardiac structure and function and heart failure risk in a biracial cohort of community-dwelling elderly persons: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;1:173–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tapson VF, Decousus H, Pini M, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients. Chest 2007;132:936–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darze ES, Latado AL, Guimaraes AG, et al. Acute pulmonary embolism is an independent predictor of adverse events in severe decompensated heart failure patients. Chest 2007;131: 1838–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samama MM, Cohen AT, Darmon J-Y, et al. A comparison of enoxaparin with placebo for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med 1999;341: 793–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen AT, Harrington RA, Goldhaber SZ, et al. Extended thromboprophylaxis with betrixaban in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med 2016; 375:534–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland JG, Findlay I, Jafri S, et al. The Warfarin/Aspirin Study in Heart Failure (WASH): a randomized trial comparing antithrombotic strategies for patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2004;148:157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cokkinos DV, Haralabopoulos GC, Kostis JB, Toutouzas PK. Efficacy of antithrombotic therapy in chronic heart failure: the HELAS study. Eur J Heart Fail 2006;8:428–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massie BM, Collins JF, Ammon SE, et al. Randomized trial of warfarin, aspirin, and clopidogrel in patients with chronic heart failure: the Warfarin and Antiplatelet Therapy in Chronic Heart Failure (WATCH) trial. Circulation 2009; 119:1616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma S, Thompson JL, Pullicino PM, et al. Warfarin and aspirin in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. N Engl J Med 2012;366: 1859–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zannad F, Anker SD, Byra WM, et al. Rivaroxaban in patients with heart failure, sinus rhythm and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2018; 379:1332–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lip GYH, Lowe GDO, Metcalfe MJ, Rumley A, Dunn FG. Is diastolic dysfunction associated with thrombogenesis? A study of circulating markers of a prothrombotic state in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol 1995;50:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doukky R, Garcia-Sayan E, Patel M, et al. Impact of diastolic function parameters on the risk for left atrial appendage thrombus in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: a prospective study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:545–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldberg LR, Jessup M. Stage B heart failure: management of asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Circulation 2006;113: 2851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang MC, Fan D, Sung SH, et al. Outcomes in adults with acute pulmonary embolism who are discharged from emergency departments: the Cardiovascular Research Network Venous Thromboembolism study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1060–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang MC, Fan D, Sung SH, et al. Validity of using inpatient and outpatient administrative codes to identify acute venous thromboembolism: the CVRN VTE study. Med Care 2017;55:e137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.