Abstract

Cardiac rehabilitation is a comprehensive model of secondary prevention proven to reduce mortality and morbidity. The World Health Organization is developing a Package of Rehabilitation Interventions for implementation by ministries of health as part of universal healthcare across the continuum. Through a systematic review, we sought to identify the best-quality cardiac rehabilitation guidelines, and extract their recommendations for implementation by member states. A systematic search was undertaken of academic databases and guideline repositories, among other sources, through to April 2019, for English-language cardiac rehabilitation guidelines from the last 10 years, free from conflicts, and with strength of recommendations. Two authors independently considered all citations. Potentially eligible guidelines were rated for quality using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool, and for other characteristics such as being multi-professional, comprehensive and international in perspective; the latter criteria were used to inform selection of 3–5 guidelines meeting inclusion criteria. Equity considerations were also extracted. Altogether, 2076 unique citations were identified. Thirteen passed title and abstract screening, with six guidelines potentially eligible for inclusion in the Package of Rehabilitation Interventions and rated for quality; for two guidelines the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool ratings did not meet World Health Organization minimums. Of the four eligible guidelines, three were selected: the International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (2016), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (#172; 2013) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (#150; 2017). Extracted recommendations were comprehensive, but psychosocial recommendations were contradictory and diet recommendations were inconsistent. A development group of the World Health Organization will review and refine the recommendations which will then undergo peer review, before open source dissemination for implementation.

Keywords: Cardiac rehabilitation, clinical practice guidelines, ischemic heart disease, systematic review, quality, equity

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality around the globe.1 Indeed, it is one of the biggest global contributors of disability-adjusted life years.2,3 Cardiac patients are at high risk of recurrent events and of having a reduced quality of life, and hence secondary prevention, such as that delivered in cardiac rehabilitation (CR), is integral to treatment.

CR is comprised of five core components, namely nutritional counselling, risk factor modification, psychosocial management, patient education, and exercise training.4,5 Research has shown that comprehensive delivery of all core components significantly reduces morbidity and cardiovascular mortality.6 Unfortunately CR is under-implemented, and access is inequitable.7,8

As part of Sustainable Development Goal 3 on health, the World Health Organization (WHO) is committed to ensuring the full continuum of care, including rehabilitation, is offered in every country as part of universal health coverage, as outlined in their Rehabilitation 2030 initiative.9 To this end, researchers, and stakeholders from around the world have worked to develop a Package of Rehabilitation Interventions (PRI) to guide policy-makers and health care providers on how to design and implement rehabilitation services, for major health conditions including IHD.10

Prior to this report, there have been three reviews of CR guidelines to our knowledge,11–13 two of which considered quality (one only in guidelines >10 years old;12 the Abell et al. review was on exercise guidance for cardiovascular disease, not CR specifically, and did not report quality in accordance with scoring instructions)11 and two reviews focused on comparability of exercise recommendations only.11,13 The search from the most recent review, again on exercise guidance but not CR specifically, went to 2016.11 As part of the WHO PRI initiative, an updated systematic review of CR guidelines was undertaken, with an eye to identifying the highest quality, multi-professional, comprehensive (i.e. “general” as per the WHO manual), most recent guidelines (i.e. timely), that are internationally-applicable. The recommendations from the guidelines will be used to form the PRI. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to systematically review the literature for recent CR guidelines, and select the best quality guidelines (including equity considerations) to extract their recommendations.

Methods

Guideline selection and recommendation extraction was undertaken in accordance with the PRI manual provided by the WHO Rehabilitation Programme, with oversight from the Cochrane Rehabilitation group.10 A Technical Working Group (TWG) was formed by the WHO, whereby for each health condition an expert in the field was invited to chair (SG) and at least one other researcher was invited to carry out the guideline review and selection (VM, DG). These individuals were identified from organizations with expertise in providing rehabilitation and producing evidence, and attempts were made to ensure more than one health profession/discipline was represented on each TWG. Conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Search strategy and data sources

A systematic review search was performed for IHD rehabilitation clinical practice guidelines. The following search terms were recommended in the WHO manual: “ischemic heart disease” OR “ischaemic heart disease” OR “myocardial ischemia” OR “coronary artery disease” AND “rehabilitation” AND “guideline.” Also, as per the WHO manual, all searches were limited to the last 10 years, and to the English language only.

Multiple sources were searched, including academic databases and guideline repositories (Table 1). Valid subject headings, as appropriate for each database, and pertinent free-text terms were used within each concept area to ensure all potentially-relevant materials were identified. The three previous CR guideline reviews were hand-searched to identify any missed citations.11–13 The search was performed in April 2019.

Table 1.

Guideline search sources.

| Academic databases |

| Medline |

| PubMed |

| Embase |

| Emcare |

| CINAHL |

| PEDro |

| Guideline repositories/clearinghouses |

| Guidelines International Network |

| National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE; UK) |

| Australian National Health and Medical Research Council |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) |

| Canadian Medical Association Infobase of Clinical Practice Guidelines |

| New Zealand Guidelines Group eGuidelines |

| Other |

| Google Scholar |

| Professional CR society websites (including ICCPR; http://globalcardiacrehab.com/cr-guidelines/) |

| Previous CR guideline reviews11–13 |

CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; CR: cardiac rehabilitation; Embase: Excerpta Medica database; ICCPR: International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; Medline: Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online; PEDro: Physiotherapy Evidence Database.

Citation screening

Following removal of duplicates using Mendeley, two researchers (VM, DG) independently screened titles and abstracts of identified citations. Specifically, both researchers reported in an Excel file whether each citation met any of the following exclusion criteria: (a) non-guideline, (b) not rehabilitation, (c) more than 10 years old, and (d) not for IHD. Results were compared, and when there were inconsistencies a consensus decision for inclusion/exclusion was made in consultation with the chair (SG).

Similarly, the two researchers then independently considered the full-texts of the remaining citations, with decisions entered into the Excel file. At this stage, three additional exclusion criteria were applied. The first exclusion criterion pertained to conflicts of interest (financial or non-financial). Those guidelines that were funded by a commercial company (i.e. a pharmaceutical company or device company) were identified, and the TWG considered conflict declarations before making inclusion decisions. Additionally, those studies that lacked or had an unclear declaration of conflict of interest or failed to mention that those with a conflict of interest were excluded from the guideline writing group, were also scrutinized. The second exclusion criterion was lack of information on the strength of recommendations. The third and final exclusion criterion was the lack of sufficient quality (see WHO criteria below), as assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE-II) tool.14

Quality assessment

Citations meeting all of the above criteria were rated according to the AGREE-II.14 For guidelines which were updates (see Table 2), the previous versions of the guidelines were also searched for information. Two researchers (VM, DG) independently evaluated the guidelines, and if the rating on any of the items differed by more than two points, the chair (SG) reviewed the ratings to come to a consensus rating. All items were rated, but nine items (4, 7, 8, 10, 12, 13, 15, 22 and 23) were used for exclusion decisions (based on a consensus process by the WHO).10 The two exclusion criteria pertaining to quality were: (a) the total score of any of the researchers on the nine items could not be lower than 45, (b) the average score on selected items (4, 8, 12 and 22) could not be lower than three.

Table 2.

Appraisal for Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE-II) 14 consensus ratings for each potentially-eligible guideline.

| Guideline | Items and domain score % | AHA/ACCF28 | EACPR29 | ICCPR4,5 | NICE27 | SIGN26 | South American36 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: scope and purpose | 1 | 5.5 | 6 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 7 |

| 2 | 6 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 5.5 | 6 | |

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5.5 | 7 | |

| Total score % | 78 | 88 | 86 | 95 | 83 | 95 | |

| Domain 2: stakeholder involvement | 4 | 5 | 1.5 | 5 | 7 | 6.5 | 5.5 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 6.5 | 1 | |

| 6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | |

| Total score% | 40 | 24 | 67 | 100 | 90 | 60 | |

| Domain 3: rigor of development | 7 | 4.5 | 1.5 | 6 | 7 | 5.5 | 1 |

| 8 | 5 | 3.5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| 9 | 7 | 5.5 | 7 | 7 | 4.5 | 5 | |

| 10 | 1 | 2.5 | 6 | 7 | 5.5 | 1 | |

| 11 | 6.5 | 6 | 5 | 6.5 | 4 | 5.5 | |

| 12 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5.5 | 6.5 | |

| 13 | 5 | 1 | 6.5 | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| 14 | 2.5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 1 | |

| Total score % | 69 | 48 | 78 | 84 | 79 | 43 | |

| Domain 4: clarity and presentation | 15 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6 | 7 | 5.5 | 6.5 |

| 16 | 6.5 | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 6 | 6.5 | |

| 17 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5.5 | |

| Total score % | 95 | 93 | 93 | 100 | 88 | 88 | |

| Domain 5: applicability | 18 | 2.5 | 4 | 7 | 6.5 | 5 | 5.5 |

| 19 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5.5 | 6 | |

| 20 | 1 | 4.5 | 7 | 6.5 | 4 | 6 | |

| 21 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 4 | 6 | |

| Total score % | 46 | 75 | 98 | 91 | 66 | 84 | |

| Domain 6: editorial independence | 22 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 1 |

| 23 | 7 | 1 | 6.5 | 7 | 6.5 | 6 | |

| Total score % | 93 | 14 | 96 | 89 | 93 | 50 | |

| Sum of items4,7,8,10,12,13,15,22,23,a | 47 | 24.5 | 55 | 55.5 | 53.5 | 31.5 |

AHA/ACCF: American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation; EACPR: European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; ICCPR: International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation; NICE: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; SIGN: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines; WHO: World Health Organization.

AGREE-II domain scores range from 1 “strongly disagree” to 7 “strongly agree”.

As per the Methods section, WHO required the sum of these items to be ≥45. In addition, none of these items could be <3.

Guideline selection and data extraction

Finally, for guidelines that were not excluded up to this point, the WHO manual specified that 3–5 guidelines were to be selected for the PRI. To inform selection, potentially-eligible guidelines were analyzed using the WHO prioritization criteria (i.e. multi-professional, comprehensiveness, international perspective)10 and equity considerations (i.e. patient populations under-represented in CR such as women or those of lower socioeconomic status;7,8 the latter was not part of the PRI process). Ultimately, guidelines that were most recent, of the highest quality (sum of nine WHO-selected AGREE-II item ratings),10 multi-professional, comprehensive, and internationally-relevant were prioritized. The TWG discussed the potentially-eligible guideline ratings to reach a consensus on which to include in the PRI.

Data extracted from the selected guidelines was based on the Reporting Items for practice Guidelines in HealThcare (RIGHT) statement,15 and included both recommendations and level of evidence and strength of the recommendations. Equity considerations were also extracted for the purposes of this article.

Results

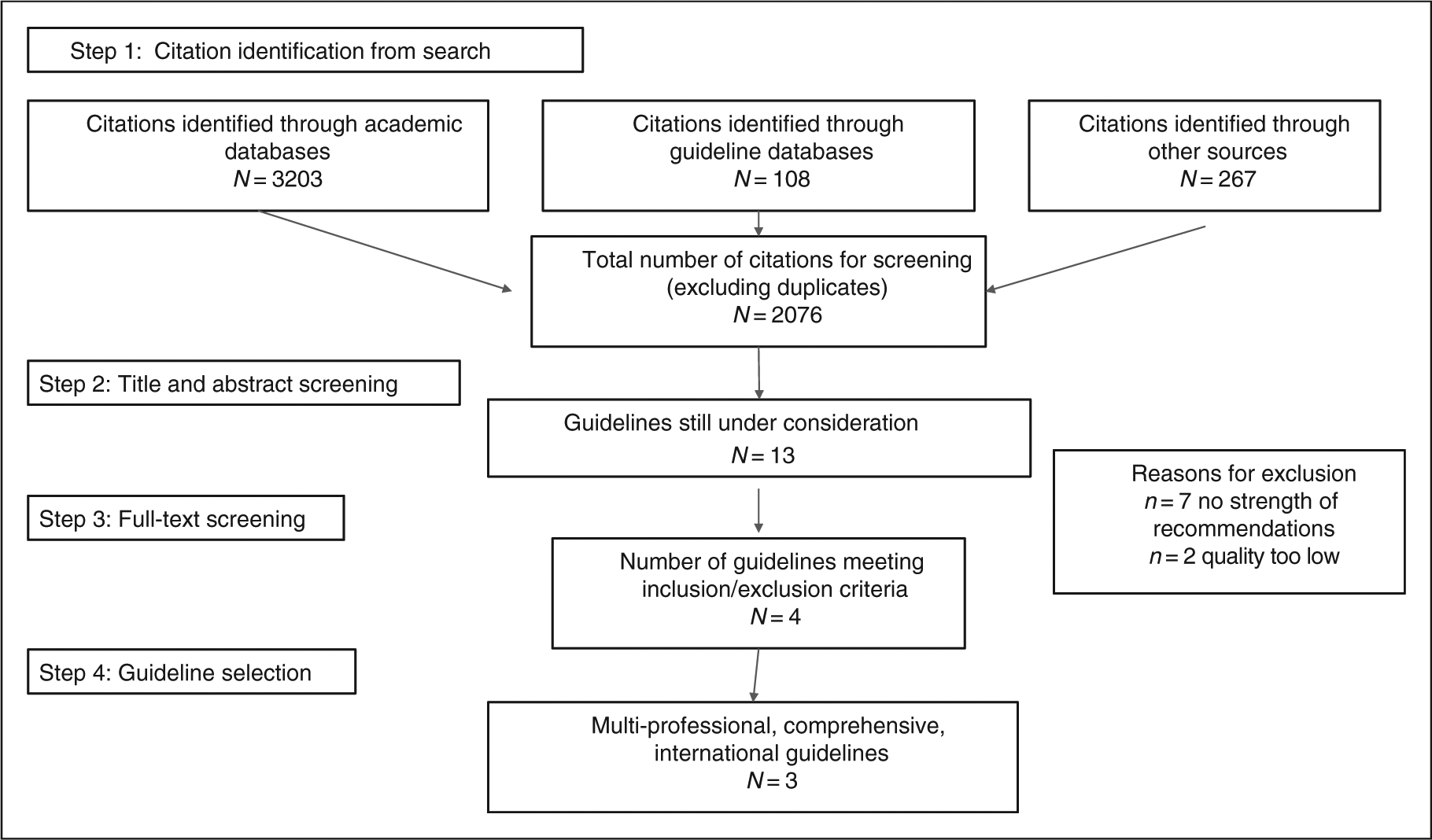

A sample search strategy is provided in Supplementary Material Table 1. Figure 1 outlines the process of guideline identification and selection. Some guidelines for secondary prevention of specific types of IHD were identified (e.g. ST-elevation myocardial infarction)16 or for specific sub-populations (e.g. women);17 these were excluded as being too narrow with regard to population. In addition, some identified guidelines focused on exercise only,18,19 and these were excluded on the basis that they were not rehabilitation interventions.

Figure 1.

Study identification and selection flow diagram.

Of the 13 potentially-eligible guidelines (Figure 1), seven did not have information on strength of recommendations and hence were not rated for quality using AGREE-II.18,20–25 For the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) guidelines,26 the quality of evidence supporting the recommendations is explicitly stated and hence these guidelines were not excluded at this stage, but each recommendation does not have specific corresponding strength/level of evidence.

Quality and other assessment of potentially-eligible guidelines

AGREE-II14 ratings of considered guidelines are displayed in Table 2. Of these six guidelines, four met both the criteria of the WHO for inclusion.4,5,26–28 Selection criteria and equity considerations are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Considerations in each potentially-eligible guideline, n = 6.

| Core components addressed/comprehensivenessa | Other WHO considerations | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guideline (timeliness) | Nutritional counselling | Risk factor modification | Psychological management | Patient education | Exercise training | Multi-professional | International perspective | Equity | (/8) |

| MHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update28,b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | 3 | ||||

| nternational Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation’s Consensus statement: Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings (2016)4,5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low-resource | 8 |

| National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE): Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease (20l3)27,b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Ethnicity/language; age; sex; socioeconomic status | 7 | |

| European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section (2010)29 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Unknown | ✓ | Older patients Women | 7 |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network’s (SIGN) Cardiac rehabilitation guidelines (2017)11,b | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Tailoring for equality and diversity | 6.5c | |

| South American guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation (2014)36 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Young and older patients women | 7 | |

| Total (/6) | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4.5 | Mean = 6.4 |

ACCF: American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA: American Heart Association; WHO: World Health Organization.

Referred to as “general” in WHO Package of Rehabilitation Interventions manual;

update;

only scored half as equity considerations mentioned, but lacked any detail.

Guideline selection

Ultimately, three guidelines4,5,26,27 were selected for the WHO PRI by the TWG. The American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines28 were not selected as they had the lowest AGREE-II rating based on the WHO scoring (Table 2), were least timely, and least comprehensive (Table 3). The three guidelines were the International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation’s (ICCPR) consensus statement on CR delivery for low-resource settings,4,5 SIGN CR guidelines (2017),26 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline on myocardial infarction: CR and prevention of further cardiovascular disease.27 All recommendations from the selected guidelines are shown in Table 4 along with level of evidence.

Table 4.

Recommendations from selected guidelines, with level of evidence, n = 3.

| National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Myocardial infarction: Cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease (2013)27,a | |

| Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation | 1.1.1 All patients (regardless of their age) should be given advice about and offered a cardiac rehabilitation programme with an exercise component. (2007) |

| 1.1.2 Cardiac rehabilitation programmes should provide a range of options, and patients should beencouraged to attend all those appropriate to their clinical needs. Patients should not be excluded from the entire programme if they choose not to attend certain components. (2007) | |

| 1.1.3 If a patient has cardiac or other clinical conditions that may worsen during exercise, these should be treated if possible before the patient is offered the exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation. For some patients, the exercise component may be adapted by an appropriately qualified healthcare professional. (2007) | |

| 1.1.4 Patients with left ventricular dysfunction who are stable can safely be offered the exercise component of cardiac rehabilitation. (2007) | |

| Encouraging people to attend | 1.1.5 Deliver cardiac rehabilitation in a non-judgemental, respectful and culturally sensitive manner. Consider employing bilingual peer educators or cardiac rehabilitation assistants who reflect the diversity of the local population. (new 2013) |

| 1.1.6 Establish people’s health beliefs and their specific illness perceptions before offering appropriate lifestyle advice and to encourage attendance to a cardiac rehabilitation programme. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.7 Offer cardiac rehabilitation programmes designed to motivate people to attend and complete the programme. Explain the benefits of attending. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.8 Discuss with the person any factors that might stop them attending a cardiac rehabilitation programme, such as transport difficulties. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.9 Offer cardiac rehabilitation programmes in a choice of venues (including at the person’s home, in hospital and in the community) and at a choice of times of day, for example, sessions outside of working hours. Explain the options available. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.10 Provide a range of different types of exercise, as part of the cardiac rehabilitation programme, to meet the needs of people of all ages, or those with significant comorbidity. Do not exclude people from the whole programme if they choose not to attend specific components. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.11 Offer single-sex cardiac rehabilitation programme classes if there is sufficient demand. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.12 Enrol people who have had an MI in a system of structured care, ensuring that there are clear lines of responsibility for arranging the early initiation of cardiac rehabilitation. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.13 Begin cardiac rehabilitation as soon as possible after admission and before discharge from hospital. Invite the person to a cardiac rehabilitation session which should start within 10 days of their discharge from hospital. (new 2013) | |

1.1.14 Contact people who do not start or do not continue to attend the cardiac rehabilitation programme with a further reminder, such as:

| |

| 1.1.15 Seek feedback from cardiac rehabilitation programme users and aim to use this feedback to increase the number of people starting and attending the programme. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.16 Be aware of the wider health and social care needs of a person who has had an MI. Offer information and sources of help on: economic issues welfare rights housing and social support issues. (new 2013) | |

| 1.1.17 Make cardiac rehabilitation equally accessible and relevant to all people after an MI, particularly people from groups that are less likely to access this service. These include people from black and minority ethnic groups, older people, people from lower socioeconomic groups, women, people from rural communities, people with a learning disability and people with mental and physical health conditions. (2007, amended 2013) | |

| 1.1.18 Encourage all staff, including senior medical staff, involved in providing care for people after an MI, to actively promote cardiac rehabilitation. (2013) | |

| Health education and information needs | 1.1.19 Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation programmes should include health education and stress management components. (2007) |

| 1.1.20 A home-based programme validated for patients who have had an MI (such as The heart manual) that incorporates education, exercise and stress management components with follow-ups by a trained facilitator may be used to provide comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation. (2007) | |

| 1.1.21 Take into account the physical and psychological status of the patient, the nature of their work and their work environment when giving advice on returning to work. (2007) | |

| 1.1.22 Be up to date with the latest DVLA guidelines. Regular updates are published on the DVLA website. (2007) | |

| 1.1.23 After an MI without complications, people who wish to travel by air should seek advice from the Civil Aviation Authority. People who have had a complicated MI need expert individual advice. (2007, amended 2013) | |

| 1.1.24 People who have had an MI who hold a pilot’s licence should seek advice from the Civil Aviation Authority. (2007) | |

| 1.1.25 Take into account the patient’s physical and psychological status, as well as the type of activity planned when offering advice about the timing of returning to normal activities. (2007) | |

| 1.1.26 An estimate of the physical demand of a particular activity, and a comparison between activities, can be made using tables of METS of different activities (for further information please refer to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website). Advise patients how to use a perceived exertion scale to help monitor physiological demand. Patients who have had a complicated MI may need expert advice. (2007) | |

| 1.1.27 Advice on competitive sport may need expert assessment of function and risk, and is dependent on what sport is being discussed and the level of competitiveness. (2007) | |

| Psychological and social support | 1.1.28 Offer stress management in the context of comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation. (2007) |

| 1.1.29 Do not routinely offer complex psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy. (2007) | |

| 1.1.30 Involve partners or carers in the cardiac rehabilitation programme if the patient wishes. (2007) | |

| 1.1.31 For recommendations on the management of patients with clinical anxiety or depression, refer to Anxiety (NICE clinical guideline 113), Depression in adults (NICE clinical guideline 90) and Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem (NICE clinical guideline 91). (2007) | |

| Sexual activity | 1.1.32 Reassure patients that after recovery from an MI, sexual activity presents no greater risk of triggering a subsequent MI than if they had never had an MI. (2007) |

| 1.1.33 Advise patients who have made an uncomplicated recovery after their MI that they can resume sexual activity when they feel comfortable to do so, usually after about four weeks. (2007) | |

| 1.1.34 Raise the subject of sexual activity with patients within the context of cardiac rehabilitation and aftercare. (2007) | |

| 1.1.35 When treating erectile dysfunction, treatment with a PDE5 inhibitor may be considered in men who have had an MI more than six months earlier and who are now stable. (2007) | |

| 1.1.36 PDE5 inhibitors must be avoided in patients treated with nitrates or nicorandil because this can lead to dangerously low blood pressure. (2007) | |

| Changing diet | 1.2.1 Advise people to eat a Mediterranean-style diet (more bread, fruit, vegetables and fish; less meat; and replace butter and cheese with products based on plant oils). (2007) |

| 1.2.2 Do not routinely recommend eating oily fish for the sole purpose of preventing another MI. If people after an MI choose to consume oily fish, be aware that there is no evidence of harm, and fish may form part of a Mediterranean-style diet. (new 2013) | |

1.2.3 Do not offer or advise people to use the following to prevent another MI:

| |

| 1.2.4 Advise people not to take supplements containing beta-carotene. Do not recommend antioxidant supplements (vitamin E and/or C) or folic acid to reduce cardiovascular risk. (2007) | |

| 1.2.5 Offer people an individual consultation to discuss diet, including their current eating habits, and advice on improving their diet. (2007) | |

| 1.2.6 Give people consistent dietary advice tailored to their needs. (2007) | |

| 1.2.7 Give people healthy eating advice that can be extended to the whole family. (2007) | |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.2.8 Advise people who drink alcohol to keep weekly consumption within safe limits (no more than 21 units of alcohol per week for men, or 14 units per week for women) and to avoid binge drinking (more than 3 alcoholic drinks in 1–2 h). (2007) |

| Regular physical activity | 1.2.9 Advise people to undertake regular physical activity sufficient to increase exercise capacity. (2007) |

| 1.2.10 Advise people to be physically active for 20–30 min a day to the point of slight breathlessness. Advise people who are not active to this level to increase their activity in a gradual, step-by-step way, aiming to increase their exercise capacity. They should start at a level that is comfortable, and increase the duration and intensity of activity as they gain fitness. (2007) | |

| 1.2.11 Advice on physical activity should involve a discussion about current and past activity levels and preferences. The benefit of exercise may be enhanced by tailored advice from a suitably qualified professional. (2007) | |

| Smoking cessation | 1.2.12 Advise all people who smoke to stop and offer assistance from a smoking cessation service in line with Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation (NICE public health guidance 1). (2007) |

| 1.2.13 All patients who smoke and who have expressed a desire to quit should be offered support and advice, and referral to an intensive support service (for example, the NHS Stop Smoking Services) in line with Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation (NICE public health guidance 1). If a patient is unable or unwilling to accept a referral they should be offered pharmacotherapy in line with the recommendations in Smoking cessation services (NICE public health guidance 10). (2007) | |

| Weight management | 1.2.14 After an MI, offer all patients who are overweight or obese advice and support to achieve and maintain a healthy weight in line with Obesity (NICE clinical guideline 43). (2007) |

| Drug therapy | 1.3.1 Offer all people who have had an acute MI treatment with the following drugs:

|

1.3.2 Ensure that a clear management plan is available to the person who has had an MI and is also sent to the GP, including:

| |

| 1.3.3 Offer all people who have had an MI an assessment of bleeding risk at their follow-up appointment. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.4 Offer an assessment of left ventricular function to all people who have had an MI. (new 2013) | |

| ACE inhibitors | 1.3.5 Offer people who present acutely with an MI an ACE inhibitor as soon as they are haemodynamically stable. Continue the ACE inhibitor indefinitely. (new 2013) |

| 1.3.6 Titrate the ACE inhibitor dose upwards at short intervals (for example, every 12–24 h) before the person leaves hospital until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached. If it is not possible to complete the titration during this time, it should be completed within 4–6 weeks of hospital discharge. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.7 Do not offer combined treatment with an ACE inhibitor and an ARB to people after an MI, unless there are other reasons to use this combination. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.8 Offer people after an MI who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor, (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.9 Renal function, serum electrolytes and blood pressure should be measured before starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB and again within one or two weeks of starting treatment. Patients should be monitored as appropriate as the dose is titrated upwards, until the maximum tolerated or target dose is reached, and then at least annually. More frequent monitoring may be needed in patients who are at increased risk of deterioration in renal function. Patients with chronic heart failure should be monitored in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). (2007) | |

| 1.3.10 Offer an ACE inhibitor to people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago. Titrate to the maximum tolerated or target dose (over a 4–6-week period) and continue indefinitely. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.11 Offer people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago and who are intolerant to ACE inhibitors an ARB instead of an ACE inhibitor. (new 2013) | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | 1.3.12 Offer aspirin to all people after an MI and continue it indefinitely, unless they are aspirin intolerant or have an indication for anticoagulation. (2007, amended 2013) |

| 1.3.13 Offer aspirin to people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago and continue it indefinitely. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.14 For patients with aspirin hypersensitivity, clopidogrel monotherapy should be considered as an alternative treatment. (2007) | |

| 1.3.15 People with a history of dyspepsia should be considered for treatment in line with Dyspepsia (NICE clinical guideline 17). (2007, amended 2013) | |

| 1.3.16 After appropriate treatment, people with a history of aspirin-induced ulcer bleeding whose ulcers have healed and who are negative for Helicobacter pylori should be considered for treatment in line with Dyspepsia (NICE clinical guideline 17). (2007, amended 2013) | |

1.3.17 Ticagrelor in combination with low-dose aspirin is recommended for up to 12 months as a treatment option in adults with ACS, that is, people:

| |

1.3.18 Offer clopidogrel as a treatment option for up to 12 months to:

| |

1.3.19 Offer clopidogrel as a treatment option for at least 1 month and consider continuing for up to 12 months to:

| |

| 1.3.20 Continue the second antiplatelet agent for up to 12 months in people who have had a STEMI and who received CABG surgery. (new 2013) | |

1.3.21 Offer clopidogrel instead of aspirin to people who also have other clinical vascular disease, in line with Clopidogrel and modified-release dipyridamole for the prevention of occlusive vascular events (NICE technology appraisal guidance 210), and who have:

| |

| Antiplatelet therapy in people with an indication for anticoagulation | 1.3.22 Take into account all of the following when thinking about treatment for people who have had an MI and who have an indication for anticoagulation:

|

1.3.23 Unless there is a high risk of bleeding, continue anticoagulation and add aspirin to treatment in people who have had an MI who otherwise need anticoagulation and who:

| |

| 1.3.24 Continue anticoagulation and add clopidogrel to treatment in people who have had an MI, who have undergone PCI with bare-metal or drug-eluting stents and who otherwise need anticoagulation. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.25 Offer clopidogrel with warfarin to people with a sensitivity to aspirin who otherwise need anticoagulation and aspirin and who have had an MI. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.26 Do not routinely offer warfarin in combination with prasugrel or ticagrelor to people who need anticoagulation who have had an MI. (new 2013) | |

1.3.27 After 12 months since the MI, continue anticoagulation and take into consideration the need for ongoing antiplatelet therapy, taking into account all of the following:

| |

| 1.3.28 Do not add a new oral anticoagulant (rivaroxaban, apixaban or dabigatran) in combination with dual antiplatelet therapy in people who otherwise need anticoagulation, who have had an MI. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.29 Consider using warfarin and discontinuing treatment with a new oral anticoagulant (rivaroxaban, apixaban or dabigatran) in people who otherwise need anticoagulation and who have had an MI, unless there is a specific clinical indication to continue it. (new 2013) | |

| Beta-blockers | 1.3.30 Offer people a beta-blocker as soon as possible after an MI, when the person is haemodynamically stable. (new 2013) |

| 1.3.31 Communicate plans for titrating beta-blockers up to the maximum tolerated or target dose - for example, in the discharge summary. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.32 Continue a beta-blocker for at least 12 months after an MI in people without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.33 Continue a beta-blocker indefinitely in people with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.34 Offer all people who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, who have left ventricular systolic dysfunction, a beta-blocker whether or not they have symptoms. For people with heart failure plus left ventricular dysfunction, manage the condition in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). (new 2013) | |

| 1.3.35 Do not offer people without left ventricular systolic dysfunction or heart failure, who have had an MI more than 12 months ago, treatment with a beta-blocker unless there is an additional clinical indication for a beta-blocker. (new 2013) | |

| Calcium channel blockers | 1.3.36 Do not routinely offer calcium channel blockers to reduce cardiovascular risk after an MI. (2007) |

| 1.3.37 If beta-blockers are contraindicated or need to be discontinued, diltiazem or verapamil may be considered for secondary prevention in patients without pulmonary congestion or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. (2007) | |

| 1.3.38 For patients who are stable after an MI, calcium channel blockers may be used to treat hypertension and/or angina. For patients with heart failure, use amlodipine, and avoid verapamil, diltiazem and short-acting dihydropyridine agents in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). (2007) | |

| Potassium channel activators | 1.3.39 Do not offer nicorandil to reduce cardiovascular risk in patients after an MI. (2007) |

| Aldosterone antagonists in patients with heart failure and left ventricular dysfunction | 1.3.40 For patients who have had an acute MI and who have symptoms and/or signs of heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, initiate treatment with an aldosterone antagonist licensed for post-MI treatment within 3–14 days of the MI, preferably after ACE inhibitor therapy. (2007) |

| 1.3.41 Patients who have recently had an acute MI and have clinical heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction, but who are already being treated with an aldosterone antagonist for a concomitant condition (for example, chronic heart failure), should continue with the aldosterone antagonist or an alternative, licensed for early post-MI treatment. (2007) | |

| 1.3.42 For patients who have had a proven MI in the past and heart failure due to left ventricular systolic dysfunction, treatment with an aldosterone antagonist should be in line with Chronic heart failure (NICE clinical guideline 108). (2007) | |

| 1.3.43 Monitor renal function and serum potassium before and during treatment with an aldosterone antagonist. If hyperkalaemia is a problem, halve the dose of the aldosterone antagonist or stop the drug. (2007) | |

| Statins and other lipid lowering agents | 1.3.44 Statin therapy is recommended for adults with clinical evidence of cardiovascular disease in line with Statins for the prevention of cardiovascular events (NICE technology appraisal guidance 94) and Lipid modification (NICE clinical guideline 67). (2007) |

| Coronary revascularisation after an MI | 1.4.1 Offer everyone who has had an MI a cardiological assessment to consider whether coronary revascularisation is appropriate. This should take into account comorbidity. (2007) |

| Selected patient subgroups | Patients with hypertension 1.5.1 Treat hypertension in line with Hypertension (NICE clinical guideline 127). (2007, amended 2013) |

| Patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction 1.5.2 Patients who have left ventricular systolic dysfunction should be considered for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator in line with Implantable cardioverter defibrillators for arrhythmias (NICE technology appraisal guidance 95). (2007) | |

| Communication of diagnosis and advice | 1.6.1 After an acute MI, ensure that the following are part of every discharge summary:

|

| 1.6.2 Offer a copy of the discharge summary to the patient. (2007) | |

| International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation’s Consensus statement: Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings (2016)4,5 | |

| Exercise | 1a. Programmes of exercise should, wherever feasible, be offered to all subjects recovering from major CHD events. (LMICs-low quality of evidence) |

| 1b. The frequency goal should be to conduct exercise training on at least three days but preferably on most days of the week. (Consensus-based) | |

| 1c. If an exercise ECG has been conducted prior to exercise, the heart rate during exercise should be kept below the symptomatic threshold. If no exercise ECG has been possible then the presence of chest pain induced by exercise and relieved by rest or nitroglycerin warrants evaluation prior to initiating exercise at intensities at or above this intensity. Without an exercise ECG, the recommended exercise training intensity should be in the light and moderate ranges.(Consensus-based) | |

| 1d. The duration of aerobic exercise training would depend on the patient’s initial functional capacity and progression in the programme and might start with a 10 min bout of aerobic exercise and gradually progress to 60min per session at a rate of about 10–20% in duration per week. Warm-up and cooldown activities would precede and follow the aerobic exercise bout. (Consensus-based) | |

| 1e. Patients at lower risk or who have completed a period of supervised rehabilitation can be promoted to exercise safely in a home-based or community setting. Supervised exercise setting is for high-risk patients. (LMICs-low quality of evidence) | |

| 1f. Walking is the preferred mode of exercise, as it is no-cost. However, non-weight-bearing exercise is recommended for patients with musculoskeletal pain or limitations. This should be augmented with resistance training where possible. (Consensus-based) | |

| Diet | 2a. Fruits and vegetables. Consumed in abundance as affordable, particularly locally grown fruits and vegetables. At least 400 g/day (i.e. five portions), but ideally double this. There should be a greater intake of vegetables than fruit. Having a variety of different coloured fruit and/or vegetables daily will aid a diverse micronutrient intake. A maximum of one glass (150 ml) of fruit juice each day. (HIC-high quality of evidence and consensus-based) |

| 2b. Whole grains and fibre. Whole grains and fibre should be incorporated into the diet in the least refined and highest fibre form. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence). Refined starches and sugars along with sugar-sweetened beverages should be limited. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 2c. Dietary fat. The primary source of fat should be an unsaturated fat (olive oil, sunflower oil, canola/rapeseed oil) replacing saturated fat (lard, butter) where possible. Trans fatty acids (partially hydrogenated fat) should be avoided. (HICs-high quality of evidence) | |

| 2d. Salt. Less than 5g salt/2000 mg sodium per day. Reduction of processed, smoked, cured, bread and cereal products will aid achievement. (HICs-high quality of evidence) | |

| 2e. Protein. Use fish, poultry, nuts and legumes as an alternative to fatty red or processed meats. For those living in coastal areas, eating fish caught locally may be more affordable. (Consensus-based) | |

| 2f. Dairy products. These are non-essential although can be useful sources of protein or calcium for some; there is no benefit from a high intake. (Consensus-based) | |

| 2g. Vitamin and mineral supplements. Not required if a balanced diet is consumed, unless indicated by other conditions. (Consensus-based) | |

| 2h. Patients with raised LDL cholesterol. The incorporation of stanol and sterol ester products can be encouraged in the correct dose. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| Tobacco | Psychological interventions 3a. For all patients: brief advice from trained health professional or physician is recommended. Brief opportunistic advice consists of up to 30min of discussion with patients aimed at prompting a quit attempt and in some cases enhancing chances of the success of that quit attempt. It can be provided by a physician, nurse or trained health personnel at the CR facility. It may include advice to stop, providing information about the health consequences of smoking, how the different components of cigarette smoke cause harm, the benefits of quitting, advice on methods of quitting and in some cases offer of further support. (LMICs-high quality of evidence). Pharmacological interventions where available: non-physician based |

| 3b. NRT products are recommended for all smokers and smokeless tobacco users with stable cardiovascular disease and those who have suffered an acute event on hospital discharge. Those with unstable disease should be assessed by a cardiologist prior to NRT use. (HICs-high quality of evidence) Pharmacological interventions options for physicians: based on availability, affordability and individual patient profile | |

| 3c. Where a physician and the medications are available and affordable, patients should be offered bupropion, cytisine or varenicline. | |

| Body weight/composition | 4a. All patients with established CHD should have serial (e.g. every six months) monitoring of BMI and waist circumference. (Consensus-based) |

| 4b. In individuals who are overweight (BMI > 25) or obese (BMI > 30), a combination of weight loss, dietary changes and physical activity is recommended. (LMICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| Education | 5a. Patient education should be personalised, led by trained staff, with regular contact between staff and patients. It should be delivered in individual and/or group settings and if possible, include family members and caregivers. Patient’s specific health goals should be discussed. (Consensus-based) |

| 5b. The aim of education should be to influence health beliefs, to elicit positive emotions, to increase optimism about the possibility of change and to heighten the salience of personal experience or other evidence supporting self-efficacy. (Consensus-based) | |

| 5c. In addition to education on physical activity, risk factor control, smoking cessation and drug treatment (where feasible), dietary education should be given in terms of food not nutrients, at an appropriate level, in order to facilitate informed healthy choices. Advice should be adapted to meet the specific needs of the patient in the context of his/her family, taking into account factors such as age, culture and lifestyle. For maximum benefit, any targets should be realistic for the longer-term to ensure life-long maintenance. (Consensus-based) | |

| Mental health | 6a. Where CR programmes have access to healthcare professionals capable of: (1) undertaking diagnostic interviews for depression and (2) providing collaborative, stepped depression treatment for those with a positive diagnosis, patients should be screened for depression. (Consensus-based) |

| 6b. Patients who receive a positive depression diagnosis should be encouraged to adhere to CR to achieve the mental health benefits. (LMICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 6c. Depression treatment, with antidepressants and/or psychotherapy should be based on patient preference and availability. Response to therapy should be monitored, and stepped where inadequate symptom reduction is achieved. Treatment should be communicated with the CR team. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) and (Consensus-based) | |

| 6d. CR programmes should offer stress management, where a trained healthcare provider is available. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| Return to work | 7a. All CR patients should undergo assessment of occupational type, employment status and desired occupational status. (Consensus-based) |

| 7b. Patients with physically demanding occupations or jobs involving public safety should undergo risk evaluation prior to return to work. Where available, treadmill testing is recommended as the modality of choice for exercise assessment, to ascertain ischaemic threshold, and electrical instability. The six-minute walk test is a viable alternative where resources do not permit treadmill testing. (Consensus-based) | |

| 7c. Low-risk individuals are those with no angina symptoms and with good functional status (able to perform >7 METS of work). These patients can return to work within two weeks of their event, preferably with some initial CR programming and a plan for ongoing contact and support. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| Lipid control | 8a. All patients with established CHD should have baseline and subsequent (e.g. every 3–6 months) on treatment lipid profile assessments where available. (Consensus-based) |

| 8b. A combination of lifestyle modifications (including dietary changes and physical activity) and pharmacotherapy (where available and affordable) is recommended for all patients. (LMICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 8c. Statin therapy, unless contraindicated (in patients with known allergic reactions to statins, active liver disease, as well as in pregnant and lactating women), is warranted for all patients with established CHD, regardless of capacity to test for baseline lipid levels. Absence of blood draw should not be a barrier to prescription of statins. Type and dose of statin is dependent on region/country-specific cost-effectiveness analysis, availability and affordability. Ideally, this should be titrated to achieve a target LDL-C of <70mg/dl, or to achieve ≥50% reduction in baseline LDL-C. (HICs-high quality of evidence) | |

| Hypertension control | 9a. All people who have CHD and heart failure are recommended to have BP assessed at initial CR sessions. Where feasible, multiple BP readings including out of office BP readings (readings in community settings, pharmacies, home) should be used to supplement readings performed in CR sessions. People with high readings assessed in a quiet, comfortable environment (i.e. ≥ 140/90 mm Hg) at two or more visits can be diagnosed with hypertension, while hypertensive urgencies and emergencies are diagnosed immediately. People on treatment for hypertension with BP readings < 140/90 mm Hg are also considered to have hypertension. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) |

| 9b. Lifestyle behaviour advice for people with hypertension as outlined previously in this document is a core aspect of hypertension management. (LMICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 9c. Where available, antihypertensive medications, outlined in the cardioprotective point below should be used in specific clinical circumstances (e.g. ACE inhibitors in heart failure). | |

| 9d. Achieving the target BP (< 140/90 mm Hg) should be the primary clinical focus. Diuretic is often the most affordable and accessible antihypertensive medication. BP control generally requires more than one drug and when three or more drugs are required, barring contraindication, one should be a diuretic. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 9e. In people with heart failure, an aldosterone antagonist is indicated where available and affordable. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 9f. In people with heart failure, a non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker should not be used. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| 9g. In people with CHD, hypotension and reducing diastolic pressure below 60 mm Hg should be avoided. Therefore, short-acting potent oral agents like nifedipine capsules should not be used. (HICs-moderate quality of evidence) | |

| Cardioprotective therapies | Access to cardioprotective therapies can be limited in LMICs. The recommendations below are only pertinent to regions where these medications are available, affordable and accessible. Unless there is a specific contraindication, history of allergy or definite history of intolerance, the following cardioprotective medications should be prescribed universally in specific scenarios as described below: 10a. Antiplatelet therapy |

| 10.al Low-dose aspirin in doses from 75–150 mg a day is recommended for all patients with a history of CHD, including those who have been revascularised. (HICs-moderate level of evidence) | |

| 10.a2 Higher doses of aspirin have not demonstrated greater clinical benefit, and they increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers. For patients intolerant or allergic to aspirin, clopidogrel at a dose of 75 mg a day can be used. (HICs-moderate level of evidence) | |

| 10.a3 Dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin plus clopidogrel or equivalent) is indicated in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary revascularisation with stents and is recommended for one year if they received a drug-eluting stent or for at least three months if they received a bare metal stent. (HICs-moderate level of evidence) | |

| 10.a4 Dual antiplatelet therapy is also recommended in patients with a history of recurrent coronary events despite appropriate medical therapy including aspirin. (Consensus-based) | |

| 10b. ACE inhibitors | |

| 10b.1 ACE inhibitors are recommended in all patients with type I or type 2 diabetes mellitus, in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction of <40% even in the absence of coronary or atherosclerotic vascular disease, and in patients with a recent anterior myocardial infarction. (HICs-moderate level of evidence) | |

| 10b.2 ARBs should also be considered. (HICs-moderate level of evidence) | |

| 10c. β-Blockers β-Blockers are indicated in all patients after an ST elevation or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction, in patients with documented ischaemia or clinical angina, and in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction below 40%, even in the absence of coronary disease. (HICs-high level of evidence) | |

| 10d. Statins Statins are recommended in every patient with CHD regardless of pre-CR lipid values. | |

| 10e. Patient education and counselling shall be provided to optimise patient medication adherence. (HICs-high level of evidence) | |

| Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network’s (SIGN) Cardiac rehabilitation guidelines (20I7)26 | |

| Referral, engagement and partner/carer involvement | • Interventions to improve self-efficacy should be considered for inclusion in a cardiac rehabilitation programme. |

| ○ Cardiac rehabilitation programmes should consider the contributions family members and carers can make to a patient’s cardiac rehabilitation. | |

| ○ Specific carer support groups could be considered to focus on the issues partners or carers may encounter in coping with their family member’s cardiac condition. | |

| ○ Cardiac rehabilitation programmes should be tailored to consider equality and diversity issues. | |

| Assessment and care planning | ○ Comorbidities should be taken into consideration in the assessment of patients attending cardiac rehabilitation to ensure a treatment plan which addresses all the long-term conditions that may be impacting on the patient’s well-being. |

| ○ All patients referred to cardiac rehabilitation should undergo an individualised assessment leading to a care plan and interventions specific to their needs. | |

| Lifestyle risk factor management | ○ Cardiac rehabilitation programmes should place equal emphasis on each of the lifestyle risk factors when supporting patients to make lifestyle changes. |

| • Patients in cardiac rehabilitation who smoke should be offered smoking cessation interventions which include contact for more than four weeks. | |

| • Smoking cessation interventions should include a combination of telephone contact, behavioural support, and self-help materials. | |

| Physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior | • Patients should be offered a cardiac rehabilitation programme which includes an exercise component to reduce cardiovascular mortality, reduce hospital readmissions and improve quality of life. |

| • Cardiac rehabilitation services should offer individualised exercise assessments, tailor the exercise component of their programmes to individual choice and deliver them in a range of settings. | |

| • Aerobic and resistance exercises should be considered as part of exercise prescription for patients attending cardiac rehabilitation. | |

| Technology-based exercise Diet | • Technology-based interventions should be considered for patients participating in cardiac rehabilitation. |

| • A range of strategies, including telephone follow up, educational tools, contracts, nutritional tools and feedback should be considered for patients in cardiac rehabilitation to enhance adherence to dietary advice. | |

| • Referral to weight-loss programmes delivered by experts should be considered for patients requiring assistance with weight management. | |

| Long-term maintenance of behavior change | • Psychoeducation (goal setting, self monitoring) should be considered for patients in cardiac rehabilitation to facilitate adherence to physical activity. |

| Psychosocial health | • Cardiac rehabilitation should incorporate a stepped-care pathway to meet the psychological needs of patients. |

| ○ To ensure clinical governance and quality, psychological therapies should be evidence based, and delivered by psychologically-trained and supervised healthcare professionals within the context of a locally-defined care pathway. | |

| ○ Assessment tools for anxiety and depression should be repeated over the course of rehabilitation as part of a clinical pathway to ensure ongoing monitoring of symptoms and provide outcome measures of care. | |

| • All patients should be offered a package of psychological care, based on a cognitive behavioural model (e.g. stress management, cognitive restructuring, communication skills) as an integral part of cardiac rehabilitation. | |

| • Cognitive behavioural therapy should be the first choice of psychological intervention for patients in cardiac rehabilitation with clinical depression or anxiety. | |

| • Cognitive behavioural therapy should be considered for patients assessed to have specific psychological needs such as support with symptom control. | |

| ○ Cognitive behavioural therapy should only be delivered by healthcare practitioners with accredited relevant competencies and approved clinical supervision. | |

| • A supervised course of full relaxation therapy should be considered for patients in cardiac rehabilitation to enhance recovery and contribute to secondary prevention. | |

| Vocational rehabilitation | • Vocational rehabilitation interventions designed to address illness perceptions relating to the likelihood of return to work should be considered for patients in cardiac rehabilitation who have the potential to continue in employment. |

| • Exercise prescription that includes a range of physical activities designed to simulate those anticipated in the workplace should be considered for patients in cardiac rehabilitation who have the potential to continue in employment. | |

| ○ Cardiac rehabilitation services should enable appropriate patients to return to work while participating in their rehabilitation programme. | |

| Medical risk management | • Non-medical prescribing should be considered within a cardiac rehabilitation setting. |

| ○ Appropriate training and evaluation of non-medical prescribers are vital to ensure safe and effective care. | |

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; ACS: acute coronary syndromes; ARB: angiotensin II receptor blocker; BP: blood pressure; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CHD: coronary heart disease; CR: cardiac rehabilitation; DVLA: Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency; ECG: electrocardiogram; HIC: high-income countries; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LMICS: low-income and middle-income countries; METS: metabolic equivalents; MI: myocardial infarction; NICE: National Institute for Clinical Excellence; NRT: nicotine replacement therapy; NSTEMI: non-ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PDE5: phosphodiesterase type 5; STEMI: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction.

Good practice points: recommended best practice based on the clinical experience of the guideline development group.

Recommended by the guideline development group based on strong evidence.

For the NICE recommendations: the wording used in each recommendation is proxy for the strength of the guideline. Words such as ‘must’ or ‘must-not’ are for recommendations that legally must be applied, whereas words like ‘offer’, ‘refer,’ and ‘advise’ are to denote strong recommendation. Finally, recommendations that are expected to do more good than harm for most people, but need to be considered by the healthcare provider on a case-to-case basis, use the word ‘consider’. However, recommendations from 2007 are not based on strength of the recommendation, thus their wording should not be interpreted to denote strength.

Discussion

This systematic review was undertaken as part of the WHO PRI initiative, to identify high-quality CR guideline recommendations, with special consideration of equity. Ultimately, four CR guidelines were eligible, being recent, apparently free of conflict of interest (but this was not explicitly stated in all guidelines, particularly older ones), evidence-based, and of sufficient quality to be considered for selection. Of these four guidelines, none were included in the Seron et al. review;12 one guideline29 and a previous version of SIGN were included in the review by Price et al.13,29 and three guidelines27–29 were included in the review by Abell et al.11 Three guidelines were ultimately selected for the WHO PRI based on quality, timeliness, and comprehensiveness, namely SIGN,26 ICCPR,4,5 and NICE27 guidelines. Overall, guidelines were comprehensive and most considered equity, including women and the elderly.

The Abell et al. review11 also rated the quality of three guidelines included in this review27–29 using AGREE-II,14 however as outlined above, they did not score the ratings in accordance with instructions, and hence any comparisons with ratings herein should be considered loosely. Of all rated guidelines, the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation’s (now European Association of Preventive Cardiology) position statement29 had the lowest quality (Table 2). It was technically a “position statement,” and therefore an application of guideline quality criteria is somewhat of a stretch. The main domains where the statement lacked quality were in terms of editorial independence and stakeholder involvement. Only the NICE27 and SIGN26 guidelines were rated highly in terms of stakeholder involvement. Notably, the SIGN26 guidelines had an accompanying lay version for patients (https://www.sign.ac.uk/assets/pat150.pdf). Finally, all guidelines, except NICE27 and SIGN,26 failed to clearly state the timing/procedure for updates.

There were some differences noted between the recommendations of selected guidelines. Exercise recommendations are compared elsewhere.11,13 Regarding diet, the ICCPR4,5 guideline focused more on food groups, with specific recommendations regarding fat and salt. The NICE27 guidelines recommended a specific diet type (i.e. Mediterranean) for patients, while also making specific recommendations regarding supplements and oily fish. The SIGN26 guidelines however, only recommended that a range of strategies be utilized to maximize dietary adherence, with no specific dietary recommendations. This is likely a reflection of the complexity of diet, and variety in foods consumed.

For mental health/psychological interventions, there were differences in the recommendations regarding cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). While the SIGN26 guidelines recommended CBT, the NICE27 guidelines recommended that CBT should not be routinely administered due to “complexity” (recommendation not updated from 2007 in 2013). All three guidelines concurred that stress management is an important part of CR, and that CBT and other psychological treatments should be administered by trained healthcare professionals. Recent evidence would suggest that patients be given CBT and/or antidepressants based on their preference, and that care be collaborative and stepped.30 Overall, stakeholders and policy-makers should apply these recommendations in accordance with their system and population needs.

It is hoped that the PRI will be implemented by ministries of health in all WHO member states, to promote development of programs delivering care in alignment with the recommendations and ensure high quality care in existing programs.31,32 However, it is known there are many barriers to guideline implementation.33 One of the major barriers is cost, and this review did not consider this aspect. The ICCPR guidelines however were developed to be low cost.4,5 Moreover, ICCPR4,5 has developed an accompanying certification program to train students and healthcare providers from multiple professions on how to deliver CR (http://globalcardiacrehab.com/training-opportunities/certification/), which could mitigate human resource challenges related to recommendation implementation. Given that it has been established there are high-quality, comprehensive, unbiased CR guidelines, the focus should turn to developing implementation tools.34

This review was limited in that only guidelines in English have been considered. We are aware of guidelines from China that were not considered.

In conclusion, through this systematic review, six English-language CR guidelines from the past 10 years were closely scrutinized. These guidelines stemmed from a global group, as well as Europe and the Americas. Most considered equity. From this set of guidelines, three high-quality, comprehensive, multi-professional, and internationally-relevant guidelines were selected for recommendation extraction based on criteria of the WHO. A development group will review and finalize all recommendations through a Delphi process, and then these recommendations will be peer-reviewed.10 We anticipate the release of the PRI open source, and working with WHO towards implementation through supporting ministries of health to offer evidence-based CR as part of universal healthcare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Alexandra Rauch of the WHO Rehabilitation Programme, who led the Rehabilitation 2030 PRI initiative, and for the methodological support of the Cochrane Rehabilitation team, including Michele Patrini. The authors are also grateful for the early efforts of Milica Lazovic and her colleagues in informing the grey literature search.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R61HL143305 and Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence P20GM103644 award from the National Institute on General Medical Sciences (DG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SL Grace is an author for one of the guidelines reviewed for this study, however, she was not involved in the inclusion/exclusion rating of the guidelines or the quality assessment process, only in training, oversight and resolving discrepancies.

References

- 1.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70: 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global burden of disease compare, https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (accessed 21 June 2019).

- 3.World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (2017, accessed 21 June 2019).

- 4.Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings: An International Council of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation consensus statement. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2016; 59: 303–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grace SL, Turk-Adawi KI, Contractor A, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation delivery model for low-resource settings. Heart 2016; 102: 1449–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabboul N, Tomlinson G, Francis T, et al. Comparative effectiveness of the core components of cardiac rehabilitation on mortality and morbidity: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2018; 7: 514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valencia HE, Savage PD and Ades PA. Cardiac rehabilitation participation in underserved populations. Minorities, low socioeconomic, and rural residents. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2011; 31: 203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colella TJF, Gravely S, Marzolini S, et al. Sex bias in referral of women to outpatient cardiac rehabilitation? A meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2015; 22: 423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Rehabilitation 2030, https://www.who.int/disabilities/care/rehab-2030/en/ (accessed 21 June 2019).

- 10.Rauch A, Negrini S and Cieza A. Towards strengthening rehabilitation in health systems: Methods used to develop a WHO Package of Rehabilitation Interventions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. Epub ahead of print 14 June 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2019.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abell B, Glasziou P and Hoffmann T. Exploration of the methodological quality and clinical usefulness of a cross-sectional sample of published guidance about exercise training and physical activity for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017; 17: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serón P, Lanas F, Ríose E, et al. Evaluation of the quality of clinical guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation: A critical review. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2015; 35: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price KJ, Gordon BA, Bird SR, et al. A review of guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation exercise programmes: Is there an international consensus? Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016; 23: 1715–1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. C Can Med Assoc J 2010; 182: E839–E842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y, Yang K, Marušic A, et al. A reporting tool for practice guidelines in health care: The RIGHT statement. Ann Intern Med 2017; 166: 128–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Circulation 2013; 127: e362–e425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women – 2011 update: A guideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 1404–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pavy B, Iliou MC, Verges-Patois B, et al. French Society of Cardiology guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation in adults. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2012; 105: 309–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: A practice guideline. Netherlands Hear J 2013; 21: 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abreu A, Mendes M, Dores H, et al. Mandatory criteria for cardiac rehabilitation programs: 2018 Guidelines from the Portuguese Society of Cardiology. Rev Port Cardiol 2018; 37: 363–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall SL and Lorenc T. Secondary prevention of coronary artery disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81: 289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Irish Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation (IACR). Cardiac rehabilitation guidelines, https://iacronline.ie/IACR-Guidelines2013.pdf (2013, accessed 23 May 2019).

- 23.Stone J, Janssen I, Lewanczuk R, et al. Canadian guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and cardiovascular disease prevention: Translating knowledge into action, https://cacpr.ca/Guidelines (2009, accessed 23 May 2019).

- 24.Achttien RJ, Staal JB, Merry AHH, et al. Royal Dutch Society for Physical Therapy. KNGF clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation, http://www.fizioterapeitiem.lv/attachments/article/112/Cardio_guideline_1_Eng.pdf (2011, accessed 23 May 2019).

- 25.American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Guidelines for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs. 5th ed Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.SIGN 150. Cardiac rehabilitation, https://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-150-cardiac-rehabilitation.html (2017, accessed 23 May 2019).

- 27.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Myocardial infarction: cardiac rehabilitation and prevention of further cardiovascular disease (Clinical guideline 172), https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg172 (2013, accessed 23 May 2019). [PubMed]

- 28.Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 Update: A guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 2011; 124: 2458–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piepoli MF, Corra U, Benzer W, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: From knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010; 17: 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jha MK, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, et al. Screening and management of depression in patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019; 73: 1827–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ögmundsdottir Michelsen H, Sjölin I, Schlyter M, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction in Sweden - evaluation of programme characteristics and adherence to European guidelines: The Perfect Cardiac Rehabilitation (Perfect-CR) study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. Epub ahead of print 26 July 2019. DOI: 10.1177/2047487319865729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abreu A, Pesah E, Supervia M, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation availability and delivery in Europe: How does it differ by region and compare with other high-income countries?: Endorsed by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019; 26: 1131–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer F, Lange K, Klose K, et al. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation–a scoping review. Healthcare 2016; 4: E36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC and Bhattacharyya OK. The development of guideline implementation tools: A qualitative study. CMAJ Open 2015; 3: E127–E133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herdy AH, Lpez-Jiménez F, Terzic CP, et al. South American guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. Arq Bras Cardiol 2014; 103: 1–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.