Abstract

Background:

Alzheimer disease is a progressive neurodegenerative disease, affecting a very high proportion of the aging population. Several studies have demonstrated that one of the main contributors to this disease is oxidative stress (OS), which causes peroxidation of protein, lipids, and DNA resulting in the formation of advanced glycosylated end products (AGE) in the brain tissues. These AGE are usually associated with the amyloid β (Aβ), which could further aggravate its toxicity and its clearance. Antioxidants counteract the deterioration caused by OS.

Objective:

We aimed to evaluate the effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin on primary cortical neuronal cultures exposed to Aβ1-42 toxicity for different time periods.

Methods:

Primary cortical neuronal cultures were set up and exposed to Aβ1-42 for up to 72 hours. Cell viability was studied by 3[4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl]-2,5-dipheyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. Biochemical assays for OS such as lipid peroxidation, reduced Glutathione(GSH), Glutathione S-transferase (GST), catalase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were conducted. Sandwich enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to study the neurotrophic growth factor (NGF) expression.

Results:

Treatments with Aβ1-42 caused an elevation in lipid peroxidation products, which were ameliorated in the presence of vitamin D3 and curcumin. Both enzymatic (GST, catalase, and SOD) and nonenzymatic antioxidants (reduced GSH) were raised significantly in the presence of vitamin D3 and curcumin, which resulted in the better recovery of neuronal cells from Aβ1-42 treatment. Treatment with vitamin D3 and curcumin also resulted in the upregulation of NGF levels.

Conclusions:

This study suggests that vitamin D3 and curcumin can be a promising natural therapy for the treatment of Alzheimer disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, vitamin D3, curcumin, protein, Oxidative stress (OS), Amyloid β

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, accounting for about 60-80% of all dementia cases. AD is a neurodegenerative disorder that is characterized by progressive loss of cognitive function, accumulation of amyloid β (Aβ) formation, and deposition of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in the brain cells.1 These NFTs cause shrinkage and degeneration of neurons, consequently loss of cognitive behavior. Oxidative stress is one of the major contributing factors for the pathophysiology of AD. This oxidative stress is mediated by the generation of excess free radicals, which has the potential to attack and react with neighboring cellular components such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, resulting in cellular inflammation and Aβ deposition.2,3

Aβ production results from amyloidogenic processing of amyloid processing protein (APP): the sequential cleavage of APP by β and γ secretase.4 The cleavage products formed are Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42. . Cleavage by α-secretase of APP within the Aβ segment (nonamyloidogenic processing) prevents the formation of Aβ.4 When present in excess, Aβ1-42. are more prone to aggregate and precipitate in brain parenchyma to form plaques. In addition to several lipids that contribute to generation, degradation, and aggregation of Aβ peptides, it has been reported that fat-soluble vitamin D plays an important role in the clearance of these Aβ aggregates.5-7 Recently, curcumin has been targeted for AD therapy because of its pleiotropic effect including anti-amyloid, anti-inflammatory, and as a potent antioxidant. A recent study found that low-dose curcumin effectively disaggregates Aβ, as well as prevent fibril and oligomer formation, reiterating its potential use as therapy for AD.8

In light of the above, this study was conducted to evaluate in detail the neuroprotective role of vitamin D, curcumin, and their combined synergistic effect on Aβ1-42 toxicity to the primary cortical neuronal cultures.

Methods

Primary neuronal cortical culture

Four brains of 1 week old Wistar albino rats were used for this study. The rats were kept at a facility of King Saud University research center under the strict guidelines provided by the Experimental Animal Laboratory and approved by the animal care and use committee at the College of Applied Medical Sciences at King Saud University (approval number KSU-SE-18-01). Primary cortical neuronal cells were set up using the same protocol in our lab as described by AlJohri et al.9 The cells were plated onto 12-well and 96-well, poly-lysine-coated cell culture dishes (Millipore company) with a plating density of 5 × 106 cells/mL.

Treatment of cells

Just after plating, cells were divided into the following groups. The cells were treated with Aβ1-42 (Millipore Cat no. AG542). Curcumin was bought from Sigma Aldridge UK and stock solution of 10 mM was made with absolute ethanol. Vitamin D3 was bought online from Amazon as 1000× stock solution:

Control Group 1: The control cells maintained in similar conditions and time without any treatment.

Control Group 2: The control cells maintained in similar conditions and time treated with 1% vehicle (ethanol).

Group 3: The cells treated with 1 µM of Aβ1-42.

Group 4: The cells treated with 1 µM of Aβ1-42 + 1 nM vitamin D3.

Group 5: The cells treated with 1 µM of Aβ1-42 + 5 µM curcumin.

Group 6: The cells treated with 1 µM of Aβ1-42 + 1 nM vitamin D3 + 5 µM curcumin.

All the above concentrations were chosen based on the previous studies. All the cultures were maintained in triplicates for up to 72 hours at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% carbon dioxide.

MTT cell proliferation assay

For 3[4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl]-2,5-dipheyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay the MTT cell growth Kit from Millipore (CT02) was employed. The cells were plated on a 96-well plates with a cell density of 1 × 104/well and treated in different groups as described above and maintained in 100 µL of DMEM F12 medium + 100 units of penicillin and streptomycin + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Wells with medium without FBS was taken as a negative control. The cells were grown for 24 hours, after that they were treated with 0.5 mM H2O2 for 2 hours. The control cells were plated in the same conditions without any treatments. After this 10 µL of MTT solution (2-5-dipheyltetrazolium sodium bromide in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) was added and incubated in its presence for 4 hours. After that 100 µL of isopropanol in 0.04 N HCl was added to each well. The absorbance was read at 490 nm within 1 hour with a Bio-Rad (USA) microplate reader. Each sample was done in triplicate wells. The cell growth curve was determined using the average absorbance at 490 nm from triplicate samples of 3 independent experiments.

Lactate dehydrogenase activity

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in the culture medium and cortical cells was measured by a modification of a colorimetric routine laboratory method by Smith et al.10 Briefly, 1 mL of culture medium or cell lysate (Cells were lysed by 1% Triton X100) was incubated with 0.2 mmol/L β-NADH and 0.4 mmol/L pyruvic acid diluted in PBS of pH 7.4. The LDH concentration in the sample was proportional to the linear decrease in the absorbance at 334 nm. The LDH concentration was calculated using a commercial standard.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Lipid peroxidation was calculated using the method of Garcia et al11 using the thiobarbiturate reactive substances (TBARS) assay. Values were expressed as mM of malonaldehyde (MDA) formed hour/5 × 106 cells.

Glutathione S-transferase assay

The activity of Glutathione S-transferase (GST) was assayed in a reaction mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer (PBS), pH 6.5, 1 mM 1-Chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (CDNB), and 1 mM reduced GSH. The reaction was initiated by adding 10 µl of cell lysate and formation of S-(2, 4-dinitrophenyl) glutathione (DNP-GSH) was measured spectrophotometrically as Units per minute 5 × 106 cells.9,12

Reduced glutathione GSH assay

The estimation was carried out by the method of Beutler et al.13 Double-distilled water (1.5 mL) was added to 1 mL of cell lysate and treated with 0.6 mL of precipitating reagent (containing 1.67 g of glacial metaphosphoric acid, 0.2 g of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA], and 30.0 g of sodium chloride [NaCl] made up to 100 mL with double distilled water). The above reaction mixture was centrifuged at 1200g for 10 minutes. To 0.3 mL of supernatant, 2 mL of Na2HPO4 (0.3 M) and 0.25 mL of 5,5′-dithio-bis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DNTB, 0.4% in 1% sodium citrate) were added, and volume was made up to 3 mL with double distilled water (DDW). The optical density (OD) was read at 412 nm against the blank. Values were expressed as μg of reduced GSH/No. of cells present.

Catalase enzyme assay

Catalase activity (CAT) was estimated in the cell lysate by the method of Aebi.14 The reaction mixture in a total volume of 3 mL contained 0.4 M PBS of pH 7.2. The reaction was started by adding 1.2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and reading the change in absorbance at 240 nm for 2 minutes. One unit of CAT activity was defined as micromole of H2O2 decomposed per minute using the molar coefficient of H2O2 (43.6 M−1C−1).

Measurement of SOD

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was measured by the method described by Kakkar et al.15 Cell lysate from all groups of treatment was grown for 72 hours. The assay mixture contains 0.1 mL of phenazine methosulphate (186 µM), 0.3 mL of nitro blue tetrazolium (300 µM), 0.1 mL of cell lysate in 1 mL of distilled water, and 1.2 ml of sodium pyrophosphate buffer (pH 8.3). The reaction was stopped by the addition of glacial acetic acid and absorbance was measured at 560 nm. The SOD was calculated by % inhibition of NBT reduction = control OD − treated OD/control OD × 100. A 50% inhibition was considered as I unit.

Measurement of nerve growth factor (NGF assay)

Rat β-NGF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit Cat no. RAB0381 was purchased from Sigma Aldrich USA. A 100 µL of conditioned medium was used for each assay. The amount of NGF released into the culture medium (conditioned medium) was measured by the above chemokine sandwich ELISA kit according to the protocol provided by the company.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using statistical applications of Prism (version 7.0a). The data were statistically expressed in (mean ± standard deviation). Independent sample t-test was performed to assess the difference between control and treated groups. Comparison between control and treated groups were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A probability value P < .05 as significant and P < .001 was considered to be more significant.

Results

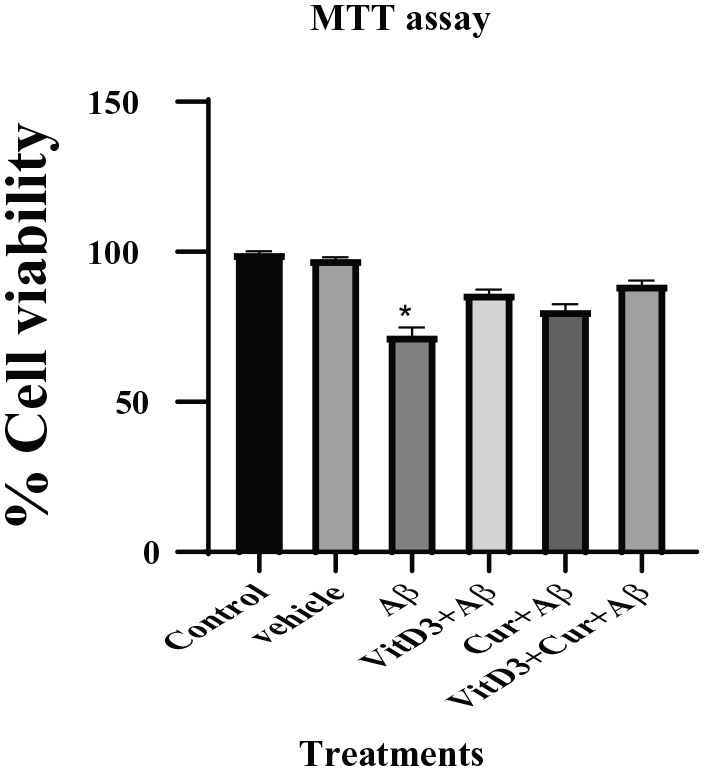

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on cortical neuron cell viability

The effect of the treatment of Aβ1-42 to the primary cortical cultures were studied at 24, 48, and 72 hours by MTT and LDH assay. The MTT assay measures the metabolic activity of mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase. The viable rapidly proliferating cells are very active metabolically, and they show dark purple staining due to the reduction of tetrazolium compound into formazan. Our results showed that there was no significant difference in the MTT absorbance when the cells were treated for 24 or 48 hours with Aβ1-42 as compared with the control cells (Table 1). However, the cells grown in the presence of Aβ1-42 for 72 hours showed decreased cellular metabolic activity as indicated by their absorbance spectra (Table 1). When the percentage cell viability of the control and different treatments group was calculated at 72 hours as shown in Figure 1, it showed a significant difference (P < .05) between the control and the Aβ1-42 treated samples. However, in the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both curcumin + vitamin D3, the cells showed improved cell viability as compared with the Aβ1-42 treated samples only.

Table 1.

MTT Assay.

| Treatments group | MTT assay/absorbance at

630 nM |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | 48 hours | 72 hours | |

| Group 1 (control) | 0.313 ± 0.004 | 0.83325 ± 0.05 | 0.3560 ± 0.09 |

| Group 2 (vehicle) | 0.43225 ± 0.03 | 0.71125 ± 0.07 | 0.3400 ± 0.04 |

| Group 3 (Aβ1-42) | 0.37725 ± 0.05 | 0.82525 ± 0.15 | 0.1834 ± 0.02* |

| Group 4 (vit D3 + Aβ1-42) | 0.4245 ± 0.01 | 0.635 ± 0.04 | 0.3405 ± 0.09 |

| Group 5 (vit D3 + curcumin + Aβ1-42) | 0.32225 ± 0.03 | 0.71225 ± 0.06 | 0.32125 ± 0.03 |

| Group 6 (curcumin + Aβ1-42) | 0.29875 ± 0.02 | 0.84075 ± 0.11 | 0.29425 ± 0.009 |

Abbreviation: MTT, 3[4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl]-2,5-dipheyltetrazolium bromide.

MTT assay for different groups of treatments as described in methods section (*) represent significant (P < .05) as compared with control group. Each sample is done in triplicates and expressed as ±SD. Data are the average of three independent experiments.

Figure 1.

Effect of Aβ1-42 treatment on primary cortical neuronal cells grown for 72 hours in the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both of them. Control cultures were also set up with them for the same period of time without any treatments. Vehicles were treated with ethanol solvent alone to see its effect. (*) shows significant (P < .05) difference between the Aβ1-42 and control samples.

LDH is a cytoplasmic enzyme, released rapidly by the cells undergoing apoptosis, necrosis, and other forms of cellular damage. In our experiment, we found that the treatment of primary cortical neuronal cultures with Aβ1-42 did not result in cell membrane rupture or release of LDH enzyme as shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the control and the different treatments groups for 24, 48, and 72 hours. That showed that the cells were not undergoing apoptosis as a result of treatments.

Table 2.

LDH Assay.

| Treatments Group | LDH assay:

units/1.5 × 106 Cells |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | 48 hours | 72 hours | |

| Group 1 (control) | 0.1624 ± 0.0005 | 0.09664 ± 0.03 | 0.0656 ± 0.006 |

| Group 2 (vehicle) | 0.15136 ± 0.02 | 0.0624 ± 0.003 | 0.07584 ± 0.004 |

| Group 3 (Aβ1-42) | 0.14272 ± 0.004 | 0.07344 ± 0.012 | 0.07616 ± 0.001 |

| Group 4 (vit D3 + Aβ1-42) | 0.17296 ± 0.01 | 0.07904 ± 0.003 | 0.06832 ± 0.005 |

| Group 5 (vit D3 + curcumin + Aβ1-42) | 0.12752 ± 0.02 | 0.08144 ± 0.006 | 0.07104 ± 0.0003 |

| Group 6 (curcumin + Aβ1-42) | 0.11536 ± 0.02 | 0.08416 ± 0.004 | 0.05648 ± 0.009 |

Abbreviation: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

LDH assay was performed as described in methods section with different groups of treatments for 24, 48, and 72 hours. We found no significant difference in the control and Amyloid β treatments. Data are an average of each sample in triplicate and expressed as ±SD.

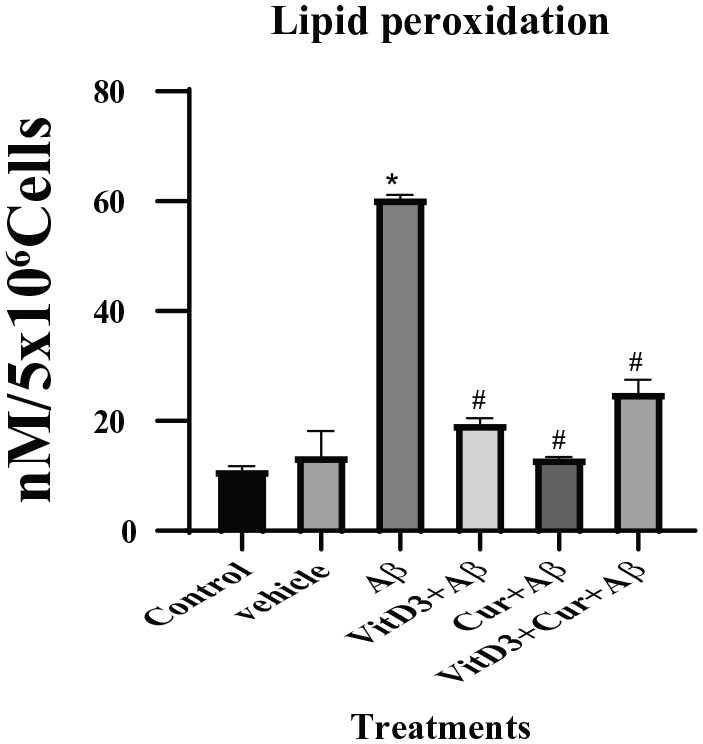

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on lipid peroxidation

Increased oxidative stress is the hallmark of Alzheimer disease. Oxidative damage is manifested in increased oxidation of lipids, which are found in abundance in the form of polyunsaturated fatty acids in the brain tissues. Our results support this notion; we found that the cells treated with Aβ1-42 showed a more significant increase (P < .001) in malonaldehyde (MDA) formation which is the end product of lipid peroxidation. However, in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin, there was significantly (P < .05) reduced MDA formation (Figure 2). In the presence of both vitamin D3 and curcumin, again the MDA formation was limited.

Figure 2.

Estimation of lipid peroxidation by measuring MDA by spectroscopic procedure described in methods section. Cell lysate from 72 hours control cell cultures and cultures treated with Aβ1-42 in the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both were used. (*) showed significant (P < .001) difference between control and Aβ1-42 treatments. (#) showed significant difference (P < .05) between Aβ1-42 alone, as well as in therapeutic presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both. MDA indicates malonaldehyde

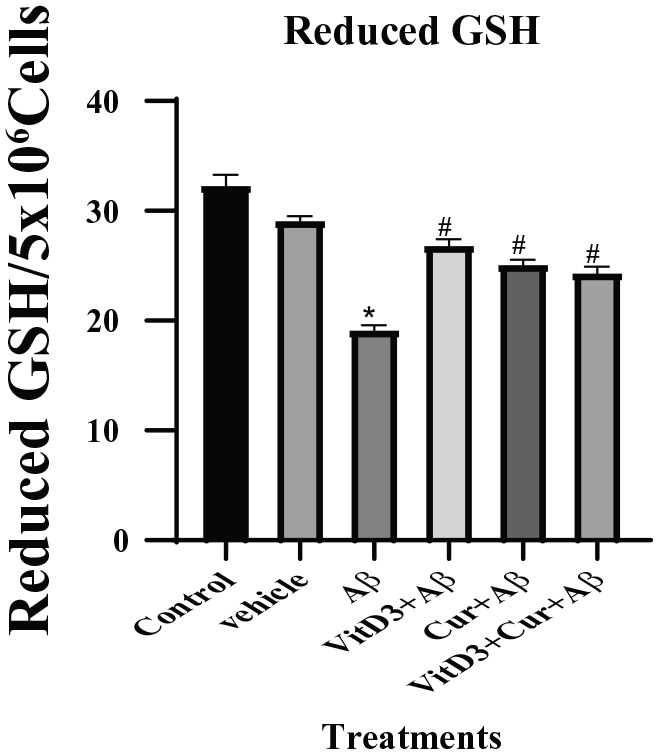

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on reduced GSH

We found that the treatment of cells with Aβ1-42 significantly reduced the reduced GSH levels when compared with the control cells, but when this treatment was done in the presence of vitamin D3, the toxic effect of Aβ1-42 was neutralized and reduced GSH was normalized. This neutralization of toxicity of Aβ1-42 was also observed significantly (P ⩽ .05) with the treatments of curcumin as well. The synergistic effect of both curcumin and vitamin D3, also resulted in a significant (P < .05) upregulation of reduced GSH in the Aβ1-42 treated cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Estimation of reduced GSH in the cell pellet of primary cortical neuronal cultured for 72 hours. Cultures treated with βA1-42 treatments were significant (*) (P < .05) from the control samples. There is a significant (#) (P < .05) recovery of the levels of reduced GSH in the presence of curcumin and vitamin D3 and both. GSH indicates glutathione.

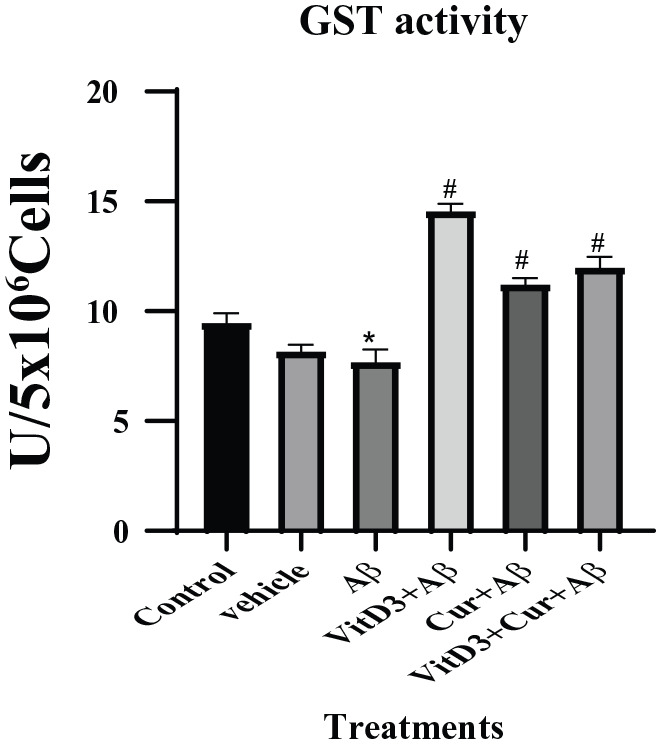

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on GST

The GSTs catalyzes the conjugation of the GSH through sulfhydryl group to an electrophilic center and help to detoxify increased products of lipid peroxidation as a result of Aβ accumulation in Alzheimer disease.16 The results showed that there was reduced GST enzyme activity in the presence of Aβ1-42. However, in the presence of vitamin D3, there was a significant (P < .05) upregulation of GST enzyme levels, which could be due to the high availability of reduced GSH as observed in earlier experiments. Treatments with Aβ1-42 in the presence of curcumin alone did not show any significant increase in GST enzyme level. The treatment with Aβ1-42 in the presence of both curcumin and vitamin D3, showed again a significantly more (P < .001) upregulation of GST activity, which clearly showed the ameliorated effect of both of these compounds (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Estimation of GST enzyme assay from primary cortical neuronal cells grown for 72 hours in the presence of Aβ1-42 alone and in the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both of them. Aβ1-42 treated cells were significant (*) (P < .05) from the control. In the presence of vitamin D3 showed more significant (#) (P < .001) recovery in the GST enzyme levels. Treatment with curcumin and both (vitamin D3 + curcumin) also showed significant recovery. GST indicates glutathione S-transferase.

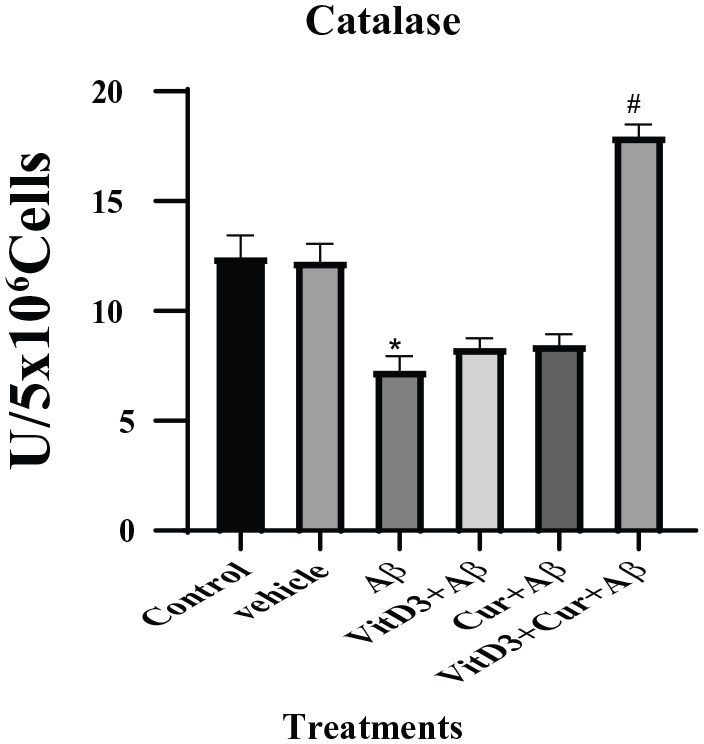

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on catalase

Our study here confirmed the earlier reports that Aβ binds with catalase enzyme and greatly reduces its activity.17 With Aβ1-42 treatment, there was significant (P < .05) reduced activity of catalase. The treatment with Aβ1-42 in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin did not have significant effect on catalase activity; however, the synergistic effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin on Aβ1-42 treated neuronal cultures was more significant (P < .001) as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Catalase enzyme levels were estimated in the primary cortical neuronal cultures grown for 72 hours in the presence and absence of Aβ1-42, as well as the effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both of them were studied. Vehicle cultures were treated with ethanol alone. There is significant (*) (P < .05) difference between the control and Aβ1-42 treated samples. A more significant (#) (P < .001) recovery was observed with Aβ1-42 treatment in the presence of vitamin D3 and curcumin.

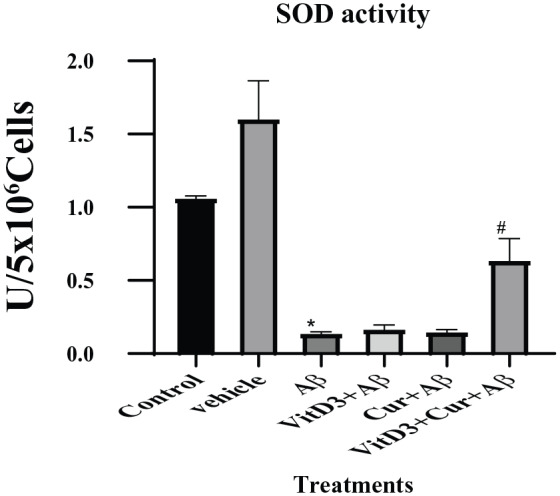

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on SOD activity

In this study, we found more significantly (P < .001) decreased activity of SOD in the Aβ1-42 treated cells. Treatment with Aβ1-42 in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin did not show any positive upregulation of the enzyme (Figure 6). However, there was a significant (P < .05) upregulation of SOD enzyme activity in the presence of both vitamin D3 and curcumin.

Figure 6.

Estimation of SOD enzyme activity as described in methods section. The cell lysate from cultures treated with and without Aβ1-42 grown for 72 hours were used to measure SOD activity. The cultures treated with Aβ1-42 were significantly (*) (P < .001) different from the control samples. However, the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin made no change to their recovery from the treatment. The synergistic effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin caused significant (#) (P < .05) recovery of SOD enzyme activity. SOD indicates superoxide dismutase.

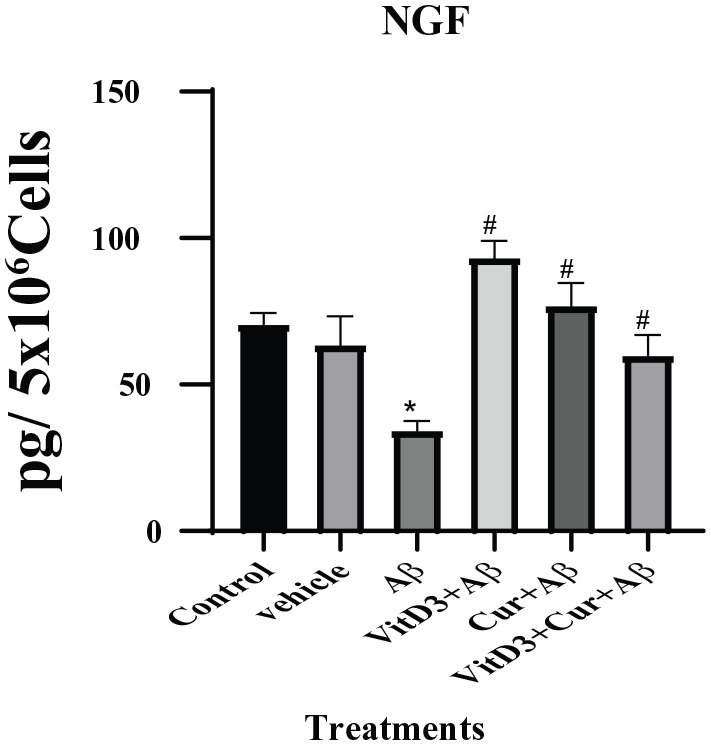

Effect of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both on NGF

The NGF is the neurotrophins ensuring the growth and survival of the nerve fibers in target neurons. In this study, we found a significant reduction (P < .05) in NGF with Aβ1-42 treatments. This inhibitory effect was ameliorated more significantly (P < .001) in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin, as well as their synergistic presence as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

NGF was measured by sandwich ELISA assay as described in methods section. Cultures were treated with Aβ1-42 alone, as well as in the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both for 72 hours. Conditioned medium from control and all the treatments groups were used for NGF assay. The treatment with Aβ1-42 resulted in significant (*) (P < .05) decrease in NGF levels but the presence of vitamin D3, curcumin, and both of them significantly (#) (P < .001) ameliorated the toxicity of NGF and upregulated the NGF synthesis. ELISA indicates enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; NGF, nerve growth factor.

Discussion

In this study, the therapeutic potential of vitamin D3, curcumin, and their combined synergistic effect was studied in an established in-vitro model of Alzheimer disease.18 The dosage of 1 µM was used for Aβ1-42 treatments, in light of the previous in vitro model studies of Alzheimer disease.19,20 The primary neuronal culture was prepared from rat’s cortex or hippocampus region that consists of mixed neuronal/astrocyte as described in our previous study.21 The optimum dosages of vitamin D3 and curcumin used in treatments were calculated in our preliminary experiments with the primary cortical neuronal cultures.9

In this study, we found that the treatments of primary cortical neuronal cells with Aβ1-42 caused a significant reduction in mitochondrial health or mitophagy as indicated by MTT assay after 72 hours in culture. As the MTT assay is based on the cellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent oxidoreductase. The cell uses the yellow tetrazolium salt which is metabolized mainly by mitochondrial succinic dehydrogenase activity of proliferating cells. Mitochondrial NADPH plays an important role in the protection against redox stress and cell death by maintaining the pool of reduced GSH and thioredoxin, which are imperative for the cellular antioxidant defense system.22 Studies have also confirmed that depletion of NADPH contributes significantly to neurotoxicity and neurodegeneration.23

The LDH enzyme is a soluble cytosolic enzyme present in the eukaryotic cells and is released into the culture medium on cell death due to rupture of cell membrane. In this study, LDH assay showed no significant difference between the control and Aβ1-42 treated cells, indicating that there is no significant death or apoptosis of neuronal cells taking place during those culture periods. From this, we concluded that the treatment of primary cortical neuronal cells with Aβ1-42 caused significantly reduced metabolically active cells, which in the long term could affect the viability of neurons. This study showed that exposure of cortical neuronal cells to Aβ1-42 resulted in slow degeneration of the cells. Other studies similar to this indicated that in mixed neuronal/astrocytes cultures prepared from rat or mouse cortex, treatments with Aβ1-42 acts preferentially on astrocytes resulting in depletion of GSH produced, which caused apoptosis of neurons eventually.18

Furthermore, we looked at the oxidative state of the primary cortical neuronal cells by measuring the lipid peroxidation (LPO) levels of different treatment groups.24 The LPO is the main contributor of free radical-mediated damage to the neuronal membrane, and it can also produce some secondary oxidation products that are capable of causing more cellular damage. These highly reactive electrophilic aldehydes are MDA and 4-hydroxy 2-nonenal (HNE). One of the earliest hallmarks of Alzheimer disease is the presence of LPO in biological fluids during the disease progression. Our study confirmed that in Alzheimer diseases there is an accumulation of oxidized lipoprotein resulting from the presence of amyloidβ.25 We found significant amount of MDA in the Aβ1-42 treated cultures, but the presence of vitamin D3 and curcumin in the culture categorically reduced its formation.

The cells are equipped with antioxidants such as GSH and antioxidant enzymes such as GST, catalase, and SOD that can quench free radicals. Recently, lipid-soluble vitamins like vitamins D and E are also characterized as antioxidants as they can relieve the cells from oxidative stress.9,26,27 The neuroprotective action of Vitamin D3 on neuronal tissue is due to the upregulation of several genes involved in alleviating oxidative stress such as reduced GSH9,28 and NGF factor.29

Studies have shown that Aβ binds specifically to catalase enzyme and inhibits the decomposition of H2O2 breakdown. It has also been reported in vitro that inhibitors of catalase—amyloid interactions can protect the neuronal cells from Aβ-induced toxicity and oxidative stress.30 We found that treatments of cells with Aβ1-42 caused significantly lower levels of catalase enzyme activity when compared with control cells. The treatment in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin did not affect the catalase enzyme activity which remained low. However, the synergistic combined effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin significantly increased the catalase enzyme expression. These results further reiterated the beneficial therapeutic effect of both, vitamin D3 and curcumin in the treatment of AD. The combined effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin has also been reported to accelerate the clearance of beta-amyloid by initiating the immune cells.31

We found that SOD enzyme activity was significantly reduced with the treatment of Aβ1-42 to the cells, but this treatment in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin did not protect the cells from amyloidβ toxicity. However, the synergistic effect of both vitamin D3 and curcumin has a positive effect in upregulating SOD enzyme activity. It has been reported that due to amyloid-beta accumulation in AD patients there is increased oxidative stress and decreased expression of SOD activity.32 In the animal model of Alzheimer disease, it was reported that overexpression of SOD prevents the memory loss and loss in cognitive behavior of mouse.33

The basal forebrain cholinergic nuclei (BFCN) represent the brain area highly susceptible to the AD. Proper functioning and morphology of this area depend on the supply of nerve growth factor from cortex and hippocampus. Several in vivo studies confirmed that the loss of NGF to the BFCN results in shrinkage and neuronal markers, which is the characteristic feature of AD.34 In recent years, targeted delivery of NGF to the affected areas of BFCN as a potential therapy for the AD patients has been gaining support, due to the regenerative effect of NGF on BFCN.35 In this study, we found that the treatment of neuronal cells with Aβ1-42 resulted in significant loss of NGF; however, this effect was neutralized in the presence of vitamin D3 or curcumin. The combined effect of vitamin D3 and curcumin was proved to be even better. Earlier studies have indicated the role of vitamin D3 in the regulation and secretion of NGF and glial-derived nerve factor (GDNF).36 Curcumin has also shown to initiate proliferation and health of neurite growth and synaptic activity.37

Although the role of Aβ1-42 as a potential causative agent in the pathophysiology of AD has been documented extensively, the exact molecular mechanisms and their biochemical effect on the brain tissues are not very clear. The in-vitro treatment of primary neuronal cultures described here tried to elicit the direct effect of Aβ1-42 on the primary neuronal cells and find out if vitamin D3 or curcumin could be used as natural therapy for its treatment. The data presented here support the notion that the treatment of primary neuronal cells with Aβ1-42 could cause elevated levels of oxidative stress, being depicted by increased amount of Lipid peroxidation products and decreased levels of antioxidants enzymes. This toxicity of Aβ1-42 and their ability to form peroxidation products from lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids can be reversed considerably in the presence of vitamin D3 and curcumin. The in-vitro model presented here would be useful in the future, to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in cause of AD and developing novel natural therapeutic strategies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our study showed that Aβ1-42 treatment caused major oxidative stress to the primary cortical neuronal cultures. Treatments with vitamin D3, curcumin, and combination of both of them resulted in significantly ameliorated the toxicity incurred by Aβ1-42 by increasing the levels of antioxidants enzymes and nerve growth factors. These studies also reiterated the importance of vitamin D3 and curcumin as a promising naturally occurring remedy for the treatment of Alzheimer disease. Although the cellular mechanism mediating the detoxification of Amyloid β is very different for both of these compounds, but their combined synergistic effect could prove to be a very effective strategy against Alzheimer disease.

Acknowledgments

The Authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for funding this work through research group No.RG-1441-534.

Footnotes

Funding:The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded by Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University (grant no. RG-1441-534).

Declaration of conflicting interests:The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: SHH contributed to study design, writing, and editing, and is the corresponding author; AA contributed to funding and supply of resources; MA contributed to experimental work and data analysis; EAA contributed to experimental work and data analysis; and MO and AA contributed to supervision and managing the project.

Data Availability: All the data, graphs, and images that support this manuscript are available on demand and if required could be available online. Any additional data could be emailed on demand.

ORCID iD: Samina Hyder Haq  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8617-3767

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8617-3767

References

- 1. Lloret A, Fuchsberger T, Giraldo E, Vina J. Molecular mechanisms linking amyloid beta toxicity and Tau hyperphosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;83:186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pohanka M. Alzheimer s disease and oxidative stress: a review. Curr Med Chem. 2014;21:356-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gandhi S, Abramov AY. Mechanism of oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2012;2012:428010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Decourt B, Sabbagh MN. BACE1 as a potential biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;24:53-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guo YX, He LY, Zhang M, Wang F, Liu F, Peng WX. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates expression of LRP1 and RAGE in vitro and in vivo, enhancing Abeta1-40 brain-to-blood efflux and peripheral uptake transport. Neuroscience. 2016;322:28-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. La Fata G, Weber P, Mohajeri MH. Effects of vitamin E on cognitive performance during ageing and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nutrients. 2014;6:5453-5472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mizwicki MT, Menegaz D, Zhang J, et al. Genomic and nongenomic signaling induced by 1alpha,25(OH)2-vitamin D3 promotes the recovery of amyloid-beta phagocytosis by Alzheimer’s disease macrophages. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;29:51-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang F, Lim GP, Begum AN, et al. Curcumin inhibits formation of amyloid beta oligomers and fibrils, binds plaques, and reduces amyloid in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5892-5901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. AlJohri R, AlOkail M, Haq SH. Neuroprotective role of vitamin D in primary neuronal cortical culture. eNeurologicalSci. 2019;14:43-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Smith SM, Wunder MB, Norris DA, Shellman YG. A simple protocol for using a LDH-based cytotoxicity assay to assess the effects of death and growth inhibition at the same time. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garcia YJ, Rodríguez-Malaver AJ, Peñaloza N. Lipid peroxidation measurement by thiobarbituric acid assay in rat cerebellar slices. J Neurosci Methods. 2005;144:127-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson JA, el Barbary A, Kornguth SE, Brugge JF, Siegel FL. Glutathione S-transferase isoenzymes in rat brain neurons and Glia. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2013-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Beutler E, Gelbart T. Improved assay of the enzymes of glutathione synthesis: gamma-glutamylcysteine synthetase and glutathione synthetase. Clin Chim Acta. 1986;158:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aebi H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kakkar P, Das B, Viswanathan PN. A modified spectrophotometric assay of superoxide dismutase. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 1984;21:130-132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sultana R, Butterfield DA. Oxidatively modified GST and MRP1 in Alzheimer’s disease brain: implications for accumulation of reactive lipid peroxidation products. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:2215-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Milton NG. Amyloid-beta binds catalase with high affinity and inhibits hydrogen peroxide breakdown. Biochem J. 1999;344:293-296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Abramov AY, Duchen MR. The role of an astrocytic NADPH oxidase in the neurotoxicity of amyloid beta peptides. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2309-2314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Calissano P, Matrone C, Amadoro G. Apoptosis and in vitro Alzheimer disease neuronal models. Commun Integr Biol. 2009;2:163-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kumaran A, Ho CC, Hwang LS. Protective effect of Nelumbo nucifera extracts on beta amyloid protein induced apoptosis in PC12 cells, in vitro model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26:172-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ain QT, Haq SH, Al-Modlej A, Alshammari A, Ahmed S, Anjum MN. Dose-dependent cytotoxicity of polyethylene glycol loaded nano-graphene oxide in cultured cerebral cortical cells. Mater Res Express. 2019;6:105405. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bradshaw PC. Cytoplasmic and mitochondrial NADPH-coupled redox systems in the regulation of aging. Nutrients. 2019;11:E504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kalisch BE, Jhamandas K, Boegman RJ, Beninger RJ. Picolinic acid protects against quinolinic acid-induced depletion of NADPH diaphorase containing neurons in the rat striatum. Brain Res. 1994;668:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bradley-Whitman MA, Lovell MA. Biomarkers of lipid peroxidation in Alzheimer disease (AD): an update. Arch Toxicol. 2015;89:1035-1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kunjathoor VV, Tseng AA, Medeiros LA, Khan T, Moore KJ. beta-Amyloid promotes accumulation of lipid peroxides by inhibiting CD36-mediated clearance of oxidized lipoproteins. J Neuroinflammation. 2004;1:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Banakar MC, Paramasivan SK, Chattopadhyay MB, et al. 1alpha, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 prevents DNA damage and restores antioxidant enzymes in rat hepatocarcinogenesis induced by diethylnitrosamine and promoted by phenobarbital. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1268-1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brennan LA, Morris GM, Wasson GR, Hannigan BM, Barnett YA. The effect of vitamin C or vitamin E supplementation on basal and H2O2-induced DNA damage in human lymphocytes. Br J Nutr. 2000;84:195-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jain SK, Micinski D. Vitamin D upregulates glutamate cysteine ligase and glutathione reductase, and GSH formation, and decreases ROS and MCP-1 and IL-8 secretion in high-glucose exposed U937 monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;437:7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. DeLuca GC, Kimball SM, Kolasinski J, Ramagopalan SV, Ebers GC. Review: the role of vitamin D in nervous system health and disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:458-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Habib LK, Lee MT, Yang J. Inhibitors of catalase-amyloid interactions protect cells from beta-amyloid-induced oxidative stress and toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38933-38943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Masoumi A, Goldenson B, Ghirmai S, et al. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 interacts with curcuminoids to stimulate amyloid-beta clearance by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:703-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ansari MA, Scheff SW. Oxidative stress in the progression of Alzheimer disease in the frontal cortex. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010;69:155-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Massaad CA, Washington TM, Pautler RG, Klann E. Overexpression of SOD-2 reduces hippocampal superoxide and prevents memory deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13576-13581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Espinet C, Gonzalo H, Fleitas C, Menal MJ, Egea J. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a neurotrophic approach. Curr Drug Targets. 2015;16:20-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eyjolfsdottir H, Eriksdotter M, Linderoth B, et al. Targeted delivery of nerve growth factor to the cholinergic basal forebrain of Alzheimer’s disease patients: application of a second-generation encapsulated cell biodelivery device . Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Orme RP, Bhangal MS, Fricker RA. Calcitriol imparts neuroprotection in vitro to midbrain dopaminergic neurons by upregulating GDNF expression. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dikmen M. Comparison of the effects of curcumin and RG108 on NGF-induced PC-12 ADH cell differentiation and neurite outgrowth. J Med Food. 2017;20:376-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]