Abstract

Background:

Long-term data on outcomes of participants hospitalized with heart failure (HF) from low- and middle-income countries are limited.

Methods and Results:

In the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry (THFR) in 2013, 1205 participants from 18 hospitals in Trivandrum, India, were enrolled. Data were collected on demographics, clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes. We performed survival analyses, compared groups and evaluated the association between heart failure (HF) type and mortality, adjusting for covariates that predicted mortality in a global HF risk score. The mean (standard deviation) age of participants was 61.2 (13.7) years. Ischemic heart disease was the most common cause (72%). The in-hospital mortality rate was higher for participants with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF; 9.7%) compared with those with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF; 4.8%; P = .003). After 3 years, 540 (44.8%) participants had died. The all-cause mortality rate was lower for participants with HFpEF (40.8%) compared with HFrEF (46.2%; P = .049). In multivariable models, older age (hazard ratio [HR] 1.24 per decade, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.15–1.33), New York Heart Association functional class IV symptoms (HR 2.80, 95% CI 1.43–5.48), and higher serum creatinine (HR 1.12 per mg/dL, 95% CI 1.04–1.22) were associated with all-cause mortality.

Conclusions:

Participants with HF in the THFR have high 3-year all-cause mortality. Targeted hospital-based quality improvement initiatives are needed to improve survival during and after hospitalization for HF.

Keywords: Heart failure, India, registry

Heart failure (HF) affects >26 million people worldwide.1 The burden of HF is increasing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), yet most available longitudinal mortality data come from North America and Europe.2 A heart failure cohort study of 5800 participants conducted in 16 LMICs revealed that the mortality rate at 1 year for acute HF was highest for participants from India (23%) and Africa (34%).3 We have previously reported an even higher 1-year mortality rate of 31% among patients with HF in southern India.4

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis on the burden of HF in 25 LMICs (n = 232,550 participants) showed that the mean age of patients with HF was 63 years, which is almost a decade younger compared with in high-income countries.2 The implications of higher mortality in a younger population with HF in India are profound, particularly given the large population estimates of HF.5 A leading research priority according to the World Health Organization is the development of observational cohorts to monitor trends of cardiovascular disease mortality to influence the policy agenda in LMICs.6 More long-term data are needed to identify targets to improve heart failure prevention, treatment, and control in India. To fill this gap, we present 3-year outcomes and predictors of mortality of participants enrolled in the first organized acute heart failure registry in India.

Methods

Study Design, Population, and Data Collection

The design of the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry (THFR) has been described previously.7 Briefly, THFR is a prospective hospital-based registry of participants with HF funded by the Indian Council for Medical Research. All 18 hospitals treating patients with HF in the district of Trivandrum in Kerala, India, participated in the registry. Patients with HF as defined by the European Society of Heart Failure were consecutively screened for enrollment in THFR from January to December 2013.8 Participants ≥18 years of age and citizens of India were eligible for inclusion in the study. Patients with septicaemia-related HF as determined by the local hospital investigator were excluded from the registry. Participants with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <45% were defined to have HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), and participants with LVEF ≥45% were defined as HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). A total of 1254 participants were assessed, and 1205 participants agreed to participate in THFR (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Trained research nurses at each participating hospital collected data with the use of a structured questionnaire (Supplemental Appendix 1). Data collected from the index hospitalization included demographics, medical history, clinical presentation, diagnostic information including laboratory values, pharmacologic treatment, and clinical outcome. Guideline-directed medical therapy on discharge was defined as the combination of beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists for patients with LVEF <45% based on clinical practice guidelines.8

Follow-up information for patients discharged from the index hospitalization was obtained every 3 months either at subsequent readmissions or by telephone. Multiple attempts were made to contact participants by telephone at each follow-up interval. If contact by telephone was unsuccessful, we attempted contact through community health staff and by mail. Data were collected at each follow-up interval and included hospital readmissions, invasive cardiac procedures, and mortality. The Institutional Ethics Committee of Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences and Technology in Trivandrum, Kerala, India, approved the study. The Indian Council of Medical Research provided financial support but did not participate in the data collection, analysis, writing, or decision to pursue publication.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of the participants enrolled in THFR are summarized for all participants and separately for participants with HFpEF and HFrEF (Table 1). Categorical variables are presented as frequencies with proportion (%) and continuous variables as means with standard deviation (SD) or, if the data were skewed, as median with interquartile range (IQR). We estimated crude all-cause mortality rates as proportions (number of deaths/total registry participants) and tested the difference in proportions. Univariate Kaplan-Meier survival plots and log-rank statistics were used to compare time and mortality across groups. Participants with missing follow-up data were right censored in the analysis. We used univariable and adjusted (for age and sex) Cox proportional hazards models to evaluate the association between HF type and mortality. An additional multivariable model was fitted that included covariates that are predictors of mortality in the HF risk score eveloped by the Meta-analysis Global Group in Chronic Heart Failure (MAGGIC).9 There was no violation of the proportional hazards assumption based on interaction with the log of time and examination of Schoenfeld residuals. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of Stata version 13 (Statacorp, College Station, Texas).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry by Heart Failure Type

| Variable | Total (n = 1205) | HFpEF (EF ≥ 45%; n = 311) | HFrEF (EF <45%; n = 894) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 61.2 (13.7) | 59.7 (14.3) | 61.8 (13.4) | .02 |

| Women, n (%) | 371 (30.8) | 122 (39.2) | 249 (27.9) | <.001 |

| Educational status, n (%) | ||||

| No education | 142 (11.8) | 28 (9.1) | 114 (12.8) | .11 |

| Up to primary | 540 (44.9) | 154 (49.8) | 386 (43.2) | |

| Secondary | 363 (30.2) | 85 (27.5) | 278 (31.1) | |

| Graduate and above | 157 (13.1) | 42 (13.6) | 115 (12.9) | |

| Acute de novo heart failure, n (%) | 479 (39.8) | 140 (45.0) | 339 (37.9) | .03 |

| Etiology of heart failure, n (%) | ||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 866 (71.9) | 189 (60.8) | 677 (75.7) | <.001 |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 156 (13.0) | 15 (4.8) | 141 (15.8) | |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 27 (2.2) | 17 (5.5) | 10 (1.1) | |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 95 (7.9) | 60 (19.3) | 35 (3.9) | |

| Hypertension | 11 (0.9) | 10 (3.2) | 1 (0.1) | |

| Miscellaneous | 50 (4.2) | 20 (6.4) | 30 (3.4) | |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | ||||

| Never used | 716 (59.4) | 215 (69.1) | 501 (56.0) | <.001 |

| Current use | 188 (15.6) | 31 (10.0) | 157 (17.6) | |

| Past use | 301 (25.0) | 65 (20.9) | 236 (26.4) | |

| Alcohol use, n (%) | ||||

| Never used | 950 (78.8) | 249 (80.1) | 701 (78.4) | .27 |

| Current use | 234 (19.4) | 54 (17.4) | 180 (20.1) | |

| Past use | 21 (1.7) | 8 (2.6) | 13 (1.5) | |

| History of hypertension, n (%) | 696 (57.8) | 171 (55.0) | 525 (58.7) | .25 |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 662 (54.9) | 161 (51.8) | 501 (56.0) | .19 |

| History of atrial fibrillation/flutter, n (%) | 177 (14.7) | 72 (23.2) | 105 (11.7) | <.001 |

| History of stroke, n (%) | 75 (6.2) | 21 (6.8) | 54 (6.0) | .65 |

| History of COPD, n (%) | 186 (15.4) | 45 (14.5) | 141 (15.8) | .58 |

| History of CKD, n (%) | 216 (17.9) | 57 (18.3) | 159 (17.8) | .83 |

| NYHA functional class, n (%) | ||||

| ≤II | 36 (3.1) | 13 (4.4) | 23 (2.7) | .33 |

| III | 744 (64.0) | 186 (62.4) | 558 (64.6) | |

| IV | 382 (32.9) | 99 (33.2) | 283 (32.8) | |

| Heart rate, beats/min, mean (SD) | 97.8 (22.5) | 97.1 (23.1) | 98.1 (22.3) | .51 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg, mean (SD) | 129.3 (32.4) | 134.3 (37.1) | 127.5 (30.3) | .002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | 80.6 (16.6) | 81.7 (17.7) | 80.2 (16.2) | .18 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.7) | 1.5 (0.9) | .02 |

| Serum hemoglobin in g/dL, mean (SD) | 12.0 (2.1) | 12.0 (2.1) | 12.0 (2.1) | .57 |

| Serum sodium, mEq/L, mean (SD) | 135.2 (6.1) | 135.8 (6.0) | 135.0 (6.2) | .06 |

| Beta-blocker on admission, n (%) | 649 (53.9) | 149 (47.9) | 500 (55.9) | .02 |

| ACE-I or ARB on admission, n (%) | 545 (45.2) | 123 (39.6) | 422 (47.2) | .02 |

HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; EF, ejection fraction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker.

Results

Demographics, Medical History, and Clinical Presentation

The mean (SD) age of participants was 61.2 (13.7) years, and fewer than one third were women (Table 1). The proportion of women was higher for HFpEF (39%) than for HFrEF (28%; P < .001). Approximately 12% of the participants had no formal education, whereas 45% had attended up to primary school. The most common cause of HF was ischemic heart disease (72%), which was more common in participants with HFrEF (76%) than in participants with HFpEF (61%; P < .001). Participants with HFrEF were more likely to use tobacco (18%) compared with those with HFpEF (10%, P < .001), whereas alcohol use was similar between HF types. Previous hypertension, diabetes, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease were similar in both groups. Participants with HFpEF (23%) were more likely to have a history of atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter compared to participants with HFrEF (12%; P < .001). Almost one third of participants (32.9%) presented with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class IV heart failure. Mean (SD) serum creatinine was 1.5 (0.9) mg/dL in participants with HFrEF compared with 1.4 (0.7) mg/dL in participants with HFpEF (P = .015). During hospital admission, 54% of participants received beta-blockers, and 45% of participants received either an ACE-I or ARB.

In-Hospital and Follow-Up Outcomes

The median (IQR) duration of index hospitalization was 6 (4–9) days and was similar between HF groups (Table 2). The total time at risk was 2215 person-years, with a median per participant follow-up of 27.2 months. In-hospital mortality was higher for participants with HFrEF (9.7%) compared with participants with HFpEF (4.8%; P = .003). After 3 years, 540 (44.8%) of all participants in THFR had died.

Table 2.

Duration of hospitalization, Follow-Up and Crude All-Cause Mortality Rates in Patients With Heart Failure in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry

| Variable | Total (n = 1205) | HFpEF (EF ≥ 45%; n = 311) | HFrEF (EF <45%; n = 894) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of index hospitalization, median (IQR) | 6 (4–9) | 6 (4–9) | 6 (4–9) | .353 |

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 102 (8.5) | 15 (4.8) | 87 (9.7) | .003 |

| Cumulative 30-day mortality, n (%) | 151 (12.5) | 25 (8.0) | 126 (14.1) | .003 |

| Cumulative 90-day mortality, n (%) | 218 (18.1) | 44 (14.2) | 174 (19.5) | .018 |

| Cumulative 1-year mortality, n (%) | 371 (30.8) | 85 (27.3) | 286 (32.0) | .061 |

| Cumulative 2-year mortality, n (%) | 492 (40.8) | 114 (36.7) | 378 (42.3) | .041 |

| Cumulative 3-year mortality, n (%) | 540 (44.8) | 127 (40.8) | 413 (46.2) | .049 |

HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; EF, ejection fraction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker.

Survival Analyses and Predictors of 3-Year All-Cause Mortality

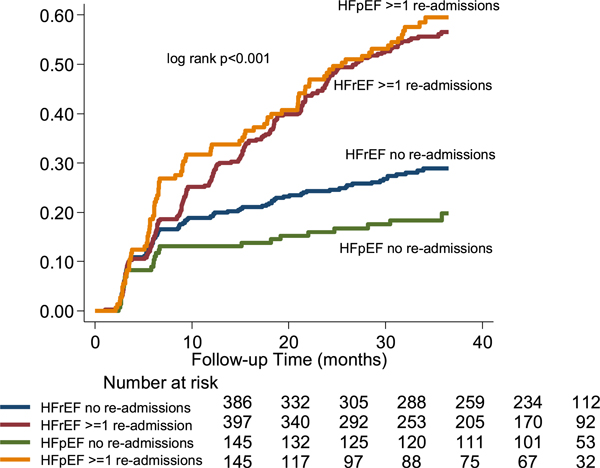

The unadjusted 3-year all-cause mortality rate was significantly lower for participants with HFpEF (40.8%) compared with HFrEF (46.2%, hazard ratio [HR] 0.82, (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.67–0.99; Table 3). The higher mortality rate for HFrEF participants over time is illustrated in the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis (Fig. 1; log-rank P = .049). After excluding the 102 participants who died during the index hospitalization in the landmark survival analysis, the all-cause mortality rate between HFrEF and HFpEF participants was similar over time (Supplemental Fig. 2; log-rank P = .354). Participants who survived the index hospitalization (landmark survival analysis) and had no additional hospital readmissions were less likely to die than participants who experienced ≥1 readmissions over time (Fig. 2; log-rank P < .001). The adverse influence of hospital readmissions on mortality was redemonstrated between participants with HFrEF and HFpEF in the landmark survival analysis (Fig. 3; log-rank P < .001). However, HFrEF participants who were discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy were less likely to die than those who did not receive guideline-directed medical therapy, and their mortality rate was similar to those with HFpEF (Fig. 4; log-rank P < .001).

Table 3.

Association of Heart Failure Type and All-Cause Mortality at 3 Years in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry

| Variable | Model 1* |

Model 2† |

Model 3‡ |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | HR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| HFpEF | 0.82 | 0.67–0.99 | .05 | 0.84 | 0.69–1.03 | .09 | 0.87 | 0.69–1.07 | .19 |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.22 | 1.14–1.30 | <.001 | 1.24 | 1.15–1.33 | <.001 | |||

| Male sex | 1.01 | 0.84–1.22 | .93 | 0.95 | 0.77–1.16 | .59 | |||

| Current smoker | 1.15 | 0.88–1.48 | .31 | ||||||

| Diabetes | 1.13 | 0.94–1.35 | .21 | ||||||

| COPD | 1.05 | 0.82–1.35 | .67 | ||||||

| SBP (per 10 mm Hg) | 0.93 | 0.90–0.96 | <.001 | ||||||

| NYHA III | 1.83 | 0.94–3.57 | .07 | ||||||

| NYHA IV | 2.80 | 1.43–5.48 | <.01 | ||||||

| Serum creatinine (per mg/dL) | 1.12 | 1.04–1.22 | <.01 | ||||||

| Beta-blocker | 0.69 | 0.57–0.82 | <.001 | ||||||

| ACE-I or ARB | 0.70 | 0.58–0.86 | <.001 | ||||||

HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; EF, ejection fraction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; NYHA, New York Heart Association; ACE-I, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker.

Model 1 is the unadjusted univariable model evaluating the relationship between HFrEF and all-cause mortality in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry.

Model 2 is adjusted for age and sex.

Model 3 is adjusted for age per 10 years, sex, current smoking status, SBP per 10 mm Hg increase, diabetes, NYHA functional class, COPD, serum creatinine, and beta-blocker and ACE-I or ARB on admission.

Fig. 1.

Heart failure type and long-term mortality rates in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (<45%); HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (≥45%).

Fig. 2.

Long-term readmission and mortality rates in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry (landmark survival analysis).

Fig. 3.

Heart failure type and long-term readmission and mortality rates in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry (landmark survival analysis). HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (<45%); HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (≥45%).

Fig. 4.

Heart failure type, guideline-directed medical therapy (GDM) and long-term mortality rates in the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (<45%); HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (≥45%).

In the multivariable Cox-proportional hazards models, the hazard of mortality for participants with HFpEF compared with HFrEF (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.69–1.03) was attenuated after adjusting for age and sex (Table 3). The hazard ratio was similar (0.87, 95% CI 0.69–1.07) after adjusting for the variables included in the prognostic MAGGIC HF risk model. Variables associated with higher mortality were age (HR 1.24 per decade increase in age, 95% CI 1.15–1.33), NYHA functional class IV symptoms during index hospitalization (HR 2.80, 95% CI 1.43–5.48), and serum creatinine (HR 1.12 per 1 mg/dL increase in serum creatinine, 95% CI 1.04–1.22). Variables associated with lower mortality rates were systolic blood pressure (HR 0.93 per 10 mm Hg increase in systolic blood pressure, 95% CI 0.90–0.96), beta-blocker use on admission (HR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57–0.82), and ACE-I or ARB use on admission (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.5–0.86).

Discussion

THFR is the first organized HF registry in India to report 3-year outcomes of participants hospitalized for HF. The most common cause of HF was ischemic heart disease. During the index hospitalization, HFrEF participants experienced higher in-hospital mortality compared with HFpEF participants. This increase in mortality for HFrEF participants was sustained over time. At 3 years, almost one half of the registry participants had died. Predictors of higher mortality included increasing age, increasing serum creatinine, and NYHA functional class IV HF. Participants discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy and those who experienced no hospital readmissions survived longer, suggesting important targets for future quality improvement initiatives.

More than 70% of participants in THFR presented with HF due to ischemic heart disease, a higher proportion compared with other multicenter acute HF registries worldwide. In Asia and the Middle East, ADHERE-AP reported that 50% of 10,171 participants and Gulf CARE that 47% of 4,539 participants had a history of coronary artery disease.10,11 In Europe, EHFS II observed that 54% of 3580 participants and ESC-HF Long Term Registry 54% of 4449 acute HF participants had a history of coronary heart disease.12,13 Similarly in North America, OPTIMIZE-HF observed that 46% of 48,612 participants had an ischemic cause of HF.14 The data available on HF in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrate the most common cause to be hypertension, although access to diagnostic tools is limited in much of the region.15 Given the particularly high burden of HF related to ischemic heart disease in southern India, public health interventions focused on prevention of ischemic heart disease and associated risk factors are essential to combat the increasing epidemic of HF.

In-hospital mortality was higher, at 8.5%, in THFR than in most other acute HF registries in LMICs in the Asia Pacific (ADHERE-AP, 4.8%), the Middle East (Gulf CARE, 6.5%), and sub-Saharan Africa (THESUS-HF, 4.2%).10,11,15 Few hospital-based HF registries in LMICs have reported longitudinal outcomes. Participants in THFR experience higher mortality rates over time compared with participants from other registries, such as INTER-CHF, the Middle Eastern Gulf CARE registry, and the sub-Saharan THESUS-HF registry.3 The highest risk of death in THFR occurred during the first 3 months after discharge from the index hospitalization and remained higher for HFrEF patients compared with HFpEF patients over the course of the study.7 It is striking that almost one-half of the study population in THFR had died at 3 years. In the Framingham Heart Study, age-adjusted mortality rates for community participants with HF in the United States reached similar levels at 5 years.16 Participants from North America and Europe enrolled in acute HF trials have lower mortality rates than THFR, highlighting the inequities between HF care in high-income versus and LMICs.17,18

Hospital readmissions were associated with mortality for both HFrEF and HFpEF patients in THFR, consistent with previous observational registry and clinical trial data. The participants with no hospital readmissions after discharge from the index hospitalization had the greatest chance of survival over 3 years, highlighting the importance of transitional care services. Focused HF clinics, nurse home visits, and structured telephone support may be important interventions to improve HF mortality in southern India.19

The use of ACE-Is or ARBs, beta-blockers, and aldosterone receptor antagonists increased modestly during hospitalization, and a greater proportion of participants were discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy.7 Participants with left ventricular systolic dysfunction who were discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy were more likely to survive over 3 years than those who were not on guideline-directed medical therapy in THFR. Predictors of mortality in our study population are consistent with the MAGGIC HF risk model based on pooled data from >39,000 patients from 30 different studies.9 Increasing age, NYHA functional class IV symptoms, and increasing serum creatinine are predictors of higher mortality in southern India. Higher systolic blood pressure, beta-blocker, and ACE-I or ARB on admission were associated with lower death rates. These prognostic findings are similar to the International Congestive Heart Failure (INTER-CHF) cohort study and highlight important targets for intervention, although a minority of participants not on guideline-directed medical therapy may have had contraindications that we did not capture.3

In a 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of HF studies conducted in 16 LMICs, mortality at 1 year of participants recruited as hospital inpatients was highest in Africa (HR 3.7, 95% CI 2.2–6.2) and India (HR 2.4, 95% CI 1.4–4.0) compared with Southeast Asia, China, South America, and the Middle East.3 More than 70% of participants in THFR presented with acute HF due to ischemic heart disease, which is consistent with other studies estimating southern Asia to have among the world’s highest age-standardized incidence rate of acute myocardial infarction.20 The greater burden of ischemic heart disease may explain some of the higher mortality, because this population of patients has worse outcomes. This high mortality rate for acute HF in India in relatively younger participants has profound social and economic implications, stressing the public health imperative to improve delivery of care. In-hospital initiation of evidence-based medications for HF is a key predictor of long-term use as demonstrated by cohort and clinical trial data.21,22 The large difference in survival at 3 years between participants in THFR who received guideline-directed medical therapy compared with those who did not reveals an important target for in-hospital quality improvement interventions. Prescription of disease-modifying therapies at discharge is particularly relevant in southern India, where many patients have limited opportunities to be evaluated by a physician and travel far distances for follow-up appointments. Furthermore, the penetrance of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy devices in this setting is low. The first cluster-randomized stepped wedge quality improvement program for acute coronary syndromes in India may be a model to embolden similar hospital-based initiatives to improve acute HF care.23

Study Strengths and Limitations

THFR is the first organized acute HF registry in India to report 3-year outcomes and fills an important gap in the current literature on mortality due to HF in LMICs. Strengths of THFR include consecutive enrolment from both urban and rural hospitals in the district of Trivandrum in Kerala, India. In addition, THFR characterizes both the HFpEF and the HFrEF populations over time. Limitations include the observational study design, which is susceptible to inherent biases, lack of objective diagnostic criteria for cause of HF, and unknown doses of guideline-directed medical therapy. Another limitation is that 80 of 1205 participants (6.6%) were lost to follow-up through the end of the entire study period. However, we include ≥1 year of follow-up data for 45 of these 80 individuals. Therefore, although loss to follow-up may influence our overall estimates, the rate of missingness in the context of the overall absolute event rate (540 events; 44.8% of the overall sample) suggests that our estimates are probably close to the true mortality rates. We also report data from one state in India, which may not be generalizable to the entire country but does offer novel insights.

Conclusion

There is a relative paucity of data on longitudinal outcomes of acute HF outside North America and Europe.2 THFR fills this critical gap as the first organized hospital-based HF registry from an LMIC to report 3-year mortality data. The high mortality rates at 3 years for both HFrEF and HFpEF highlight a key role for hospital-based quality improvement initiatives to improve clinical care for patients with HF in India. The positive effect on survival for participants discharged on guideline-directed medical therapy and who experienced no hospital readmissions serves to guide local, national, and international policy on key metrics to improve health systems for HF care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Indian Council of Medical Research for funding this study. In addition, they thank Suresh Babu, Vineeth Purushothaman, Anand Kumar, Ajeesh C., Krishna Sanker, and Manas Chacko for data collection, data entry, and follow-up data collection. They also thank Dr. Priya Sosa James, Dr. Abdul Salam, and Dr. Anil Balachandran for data collection.

Funding: This study was primarily supported by Indian Council of Medical Research. P.J. is supported by a clinical and public health intermediate fellowship from the Wellcome Trust DBT India Alliance (2015–2020). A.A. receives funding from the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health, Duke Global Health Institute and Duke Hubert-Yeargen Center for Global Health. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center and National Institute of Mental Health, of the National Institutes of Health under award number D43TW010543. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

M.D.H. receives funding from the World Heart Federation to serve as its senior program advisor for the Emerging Leaders program, which is supported by Boehringer Ingelheim and Novartis with previous support from BUPA and Astra Zeneca. M.D.H. also receives support from the American Heart Association, Verily, and Astra Zeneca for work unrelated to this research.

Footnotes

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2018.05.007.

References

- 1.Ambrosy AP, Fonarow GC, Butler J, et al. The global health and economic burden of hospitalizations for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63:1123–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, et al. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis.. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dokainish H, Teo K, Zhu J, et al. Global mortality variations in patients with heart failure: results from the International Congestive Heart Failure (INTER-CHF) prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harikrishnan S, Sanjay G, Agarwal A, et al. One-year mortality outcomes and hospital readmissions of patients admitted with acute heart failure: data from the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry in Kerala, India. Am Heart J 2017;189:193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffman MD, Prabhakaran D. Heart failure: epidemiology and prevention in India. Natl Med J India 2010;23:283–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Global action plan for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2013. Available at. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/. Accessed March 29, 2018.

- 7.Harikrishnan S, Sanjay G, Anees T, et al. Clinical presentation, management, in-hospital and 90-day outcomes of heart failure patients in Trivandrum, Kerala, India: the Trivandrum Heart Failure Registry. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McMurray JJV, Adamopoulos S, et al. Task Force Members. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1787–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pocock SJ, Ariti CA, McMurray JJV, et al. Predicting survival in heart failure: a risk score based on 39 372 patients from 30 studies. Eur Heart J 2012;34:1404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atherton JJ, Hayward CS, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Patient characteristics from a regional multicenter database of acute decompensated heart failure in Asia Pacific (ADHERE International—Asia Pacific). J Card Fail 2012;18:82–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panduranga P, Al-Zakwani I, Sulaiman K, et al. Comparison of Indian subcontinent and Middle East acute heart failure patients: results from the Gulf Acute Heart Failure Registry. Indian Heart J 2016;68:S36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nieminen MS, Brutsaert D, Dickstein K, et al. EuroHeart Failure Survey II (EHFS II): a survey on hospitalized acute heart failure patients: description of population. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2725–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crespo-Leiro MG, Anker SD, Maggioni AP, et al. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Long-Term Registry (ESC-HF-LT): 1-year follow-up outcomes and differences across regions. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:613–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor CM, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Predictors of mortality after discharge in patients hospitalized with heart failure: An analysis from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Am Heart J 2008;156:662–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Damasceno A, Mayosi BM, Sani M, et al. The causes, treatment, and outcome of acute heart failure in 1006 Africans from 9 countries. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambrosy AP, Gheorghiade M, Chioncel O, Mentz RJ, Butler J. Global perspectives in hospitalized heart failure: regional and ethnic variation in patient characteristics, management, and outcomes. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2014;11:416–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greene SJ, Fonarow GC, Solomon SD, et al. Global variation in clinical profile, management, and post-discharge outcomes among patients hospitalized for worsening chronic heart failure: findings from the ASTRONAUT trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2015;17:591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feltner C, Jones CD, Cene CW, et al. Transitional care interventions to prevent readmissions for persons with heart failure. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, et al. Global and regional patterns in cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation 2015;132:1667–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gattis WA, O’Connor CM, Gallup DS, Hasselblad V, Gheorghiade M. Predischarge initiation of carvedilol in patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:1534–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Butler J, Arbogast PG, Daugherty J, Jain MK, Ray WA, Griffin MR. Outpatient utilization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors among heart failure patients after hospital discharge. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43:2036–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huffman MD, Mohanan PP, Devarajan R, et al. Effect of a quality improvement intervention on clinical outcomes in patients in India with acute myocardial infarction. JAMA 2018;319:567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.