Abstract

There is increasing evidence that chronic pain may be associated with events that occur during critical periods of development. Recent studies have identified behavioral, spinal neurophysiological and spinal/peripheral neurochemical differences in rats that have experienced neonatal bladder inflammation (NBI): a putative model of the chronically painful bladder disorder, interstitial cystitis. Stress has been shown to exacerbate symptoms of interstitial cystitis and produces bladder hypersensitivity in animal models. We recently reported that Acute Footshock-induced bladder hypersensitivity was eliminated in otherwise normal rats by prior bilateral lesions of the central nucleus of the amygdala. Since the spinal and peripheral nervous systems of NBI-treated rats are known to differ from normal rats, the present experiments sought to determine whether a supraspinal nervous system structure, the central amygdala, is still necessary for the induction of Acute Footshock-induced hypersensitivity. The effect of bilateral amygdala electrolytic lesions on Acute Footshock-induced bladder hypersensitivity in adult female rats was tested in Control rats which underwent a control protocol as neonates and in experimental rats which experienced NBI. Consistent with our previous report, in Control rats, Acute Footshock-induced bladder hypersensitivity was eliminated by bilateral Amygdala Lesions. In contrast, Acute Footshock-induced bladder hypersensitivity in NBI-treated rats was unaffected by bilateral Amygdala Lesions. These findings provide evidence that NBI results in the recruitment of substrates of bladder hypersensitivity that may differ from those of normal rats. This, in turn, suggests that unique therapeutics may be needed for painful bladder disorders like interstitial cystitis.

Keywords: Amygdala, Visceral, Hypersensitivity, Acute stress, Urinary bladder, Neonatal inflammation

1. Introduction

Acute and chronic pains originating from the urinary bladder are common clinical entities. Some conditions are easy to treat, but others, such as interstitial cystitis (IC), are conditions of bladder hypersensitivity that have proven resistant to diagnosis and treatment. IC is characterized by urinary frequency, urgency and pelvic pain (Bogart et al., 2007). Animal models of IC have generally lacked the main clinical features of IC. An exception to this generality is an animal model developed by our research group which involves a neonatal bladder inflammation (NBI) treatment. Animals treated in this manner have increased nociceptive responses to urinary bladder distension following an adult treatment, increased micturition frequency, decreased pressure/volume thresholds for activating micturition responses, nociceptive responses to intravesical ice water solutions, increased pelvic floor muscular tone and increased submucosal hemorrhages following sustained hydrodistension (Randich et al., 2006, 2009; DeBerry et al., 2007, 2010; Ness et al., 2014a). NBI is produced by infusing a yeast-derived inflammogen, zymosan, intravesically, during a critical period of development, the end of the neonatal period (P14–16). NBI experimentally mimicks the equivalent of childhood bladder infections in humans which is relevant to the pathophysiology of IC given epidemiological data (Peters et al., 2009) that suggests there were an increased number of childhood bladder infections during childhood in individuals who develop IC. Using standard histological stains, as adults, the bladders of rats given NBI look structurally normal, but neurochemical analyses of their bladders and spinal cords indicate increased nervous system neuropeptide content (DeBerry et al., 2010; Shaffer et al., 2011), opioid peptides (Shaffer et al., 2013a,b), altered GABA-A receptor expression/function (Sengupta et al., 2013; Kannampalli et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2017) and altered spinal neuronal responses to bladder distension (Ness and Randich, 2010; Kannampalli et al., 2017). It is clear that both in IC and in our animal model system of IC we are working with an altered nervous system. To date, these alterations have been limited in scope to the spinal cord and periphery.

The neuroanatomical substrates controlling normal bladder function are well-researched, but those underlying bladder pain are poorly understood (Birder et al., 2010; Lovick, 2016). Bladder pain is not only evoked by physical perturbations to the bladder, such as bacterial infections, but also can be both induced by and exacerbated by stress. In humans, flares in bladder-related symptoms correlate with exposure to a laboratory stressor (Lutgendorf et al., 2000, 2004) and increased daily life stress (Rothrock et al., 2001). Stress is the most common exacerbating factor identified by IC subjects themselves with over 60% identifying it as a contributing factor to their flares of pain (Bogart et al., 2007). It is also a pain modifying factor that clearly involves supraspinal neurological structures.

In rats, the stressors foot shock and water avoidance evoke stress responses which have been demonstrated to augment bladder nociceptive reflexes and other measures of bladder hypersensitivity (Lee et al., 2015; Robbins and Ness, 2008; Robbins et al., 2007; DeBerry et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2011). Acute footshock alters spinal neuronal responses to noxious bladder stimulation in a fashion which requires supraspinal mechanisms since spinal transection abolishs augmentation of responses (Robbins et al., 2011). Footshock also activates the stress-responsive hypothalamic pituitaryadrenal (HPA) axis (DeBerry et al., 2015: Robbins and Ness, 2008) in ways which parallel the effects of stress observed in humans. We have reported that the central amygdala is required for the expression of Acute Footshock-induced bladder hyperalgesia in healthy adult female rats (DeBerry et al., 2015; Randich et al., 2017). DeBerry has also shown that acute central amygdala activation by corticosterone microinjection was sufficient to drive bladder hyperalgesia in the absence of Acute Footshock (DeBerry et al., 2015) giving further support for a role for the amygdala in Acute Footshock-related effects. However, no published studies have examined whether stress alters bladder sensitivity in adult rats experiencing prior NBI, nor has the necessity of an intact amygdala been examined in this context. Neuroablative manipulations in which lesions can be confirmed in location and extent are standard manipulations for determining the role of central nervous system structures in behavioral phenomena.

Therefore, the current set of neuroanatomical lesion studies examined this issue by asking the question of whether the central amygdala is required for the exacerbation of bladder pain produced by Acute Footshock in adult female rats which have experienced NBI in order to determine whether neural structures altered by NBI include typical stress-related neural mechanisms. Female rats were exclusively studied since painful bladder disorders such as interstitial cystitis affect women more than men by an order of magnitude (Bogart et al 2007).

2. Results

2.1. Amygdala Lesions have no significant effects on visceromotor responses in rats receiving No Footshock treatments.

Visceromotor responses to graded urinary bladder distension were graded in a monotonic, accelerating fashion. Fig. 1A demonstrates group data for the stimulus-response functions (SRFs) obtained from the four groups of rats which received No Footshock treatments as their final experimental manipulation. Comparison of their data allows an assessment of the effect of Amygdala Lesions on baseline bladder sensory processing. A repeated-measures ANOVA analysis of these SRF data demonstrates that there were no significant differences between any of the No Footshock groups as a function of the Amygdala Lesion versus Sham Lesion pretreatment [overall ANOVA with p = 0.2417; there was a significant distension pressure effect with p < 0.001 but no pressure × group interaction]. This was true in focused statistical comparison of both the Control groups and in the NBI groups. These data suggest no tonic modulatory effects are apparent when both central amygdalae are intact. A typical example of graded visceromotor responses of an individual rat to urinary bladder distension is given in Fig. 1B.

Fig. 1.

Graded visceromotor responses to urinary bladder distension in No Footshock rats are not affected by Amygdala lesions. Abdominal electromyographic responses to graded urinary bladder distension (UBD; 10–60 mmHg) in No Footshock rats were quantified as Evoked Visceromotor Responses in rats which received either Control procedures or Neonatal Bladder Inflammation (NBI) and subsequently received Sham lesions or bilateral amygdalar lesions. In A, data are presented as group means ± SEM. The amygdalar lesions did not significantly alter the visceromotor responses to UBD in either Control or NBI groups. N = 6–8/group. Note: these data serve as control data for Figs. 2 and 3. In B, a typical example of graded visceromotor responses to UBD in a individual rat presented as peristimulus rectified electromyograms. Graded pressure in mm Hg is indicated at left. Evoked Visceromotor Response activity was calculated as the mean rectified myoelectric activity during the 20 s of UBD minus the mean ongoing myoelectric activity immediately prior to UBD.

2.2. Acute Footshock produces bladder hypersensitivity in Control rats that is mediated by the amygdalae

Fig. 2 shows the results obtained in rats receiving neonatal Control treatments. In the Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) analyses shown in the inset of Fig. 2A, the mean AUC of the Control groups receiving a Sham Lesion treatment followed by exposure to Acute Footshock (abbreviated AFS in figure) was significantly greater than that of Control group that received a Sham Lesion pretreatment and No Footshock (abbreviated NFS in figure) [p = 0.006]. In contrast, Fig. 2B shows that the mean AUC in the Control group receiving bilateral Amygdala Lesions (inset Fig. 2B) and Acute Footshock was not statistically different from the AUC of the Control group that received bilateral Amygdala Lesion pretreatments and No Footshock (p = 0.20). Moreover, the AUCs of these Amygdala Lesion rats treated with Acute Footshock were significantly less than those of the AUC of rats which received a Sham Lesion pretreatment and then were exposed to Acute Footshock (p = 0.021). A similar picture emerged using the SRF data analyses of responses evoked by individual distending pressures. A repeated-measure ANOVA comparing the Control group with (open circles) or without (solid circles) subsequent Acute Footshock treatments in Sham Lesion rats (Fig. 2A) indicated a significant between-groups effect (p = 0.007). There was also a significant effect of distending pressure (p < 0.001) in this comparison, but no interaction between pressure and group. Post-hoc contrasts at each pressure revealed significant differences between the Acute Footshock and No Footshock groups at 30, 40, 50 and 60 mmHg of distending pressures. A similar repeated-measures ANOVA comparing the individual pressure data from the NTC group that subsequently received bilateral Amygdala Lesions (Fig. 2B) revealed no significant differences between No Footshock and Acute Footshock groups on any measures. These analyses indicate that the amygdala is required for the AFS effect in the neonatal treatment Control group and is consistent with our previous reports related to rats which received no neonatal treatments at all (Randich et al., 2017).

Fig. 2.

Acute footshock produces bladder hyperalgesia in Control rats that requires the central amygdalae. Responses to graded urinary bladder distension (UBD; 10–60 mmHg) in Control rats were quantified as Evoked Visceromotor Responses following exposure to No Footshock (NFS) or Acute Footshock (AFS) procedures in rats which had received Sham lesion procedures (Panel A) or bilateral amygdalar lesions (Panel B). Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) analyses are shown in the insets. The AFS treatment significantly increased the visceromotor responses to UBD relative to NFS in the Sham Lesion rats but not in the Amygdala Lesion rats. * and ** indicate AFS data significantly different from corresponding NFS data with P < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively. N = 6–7/group.

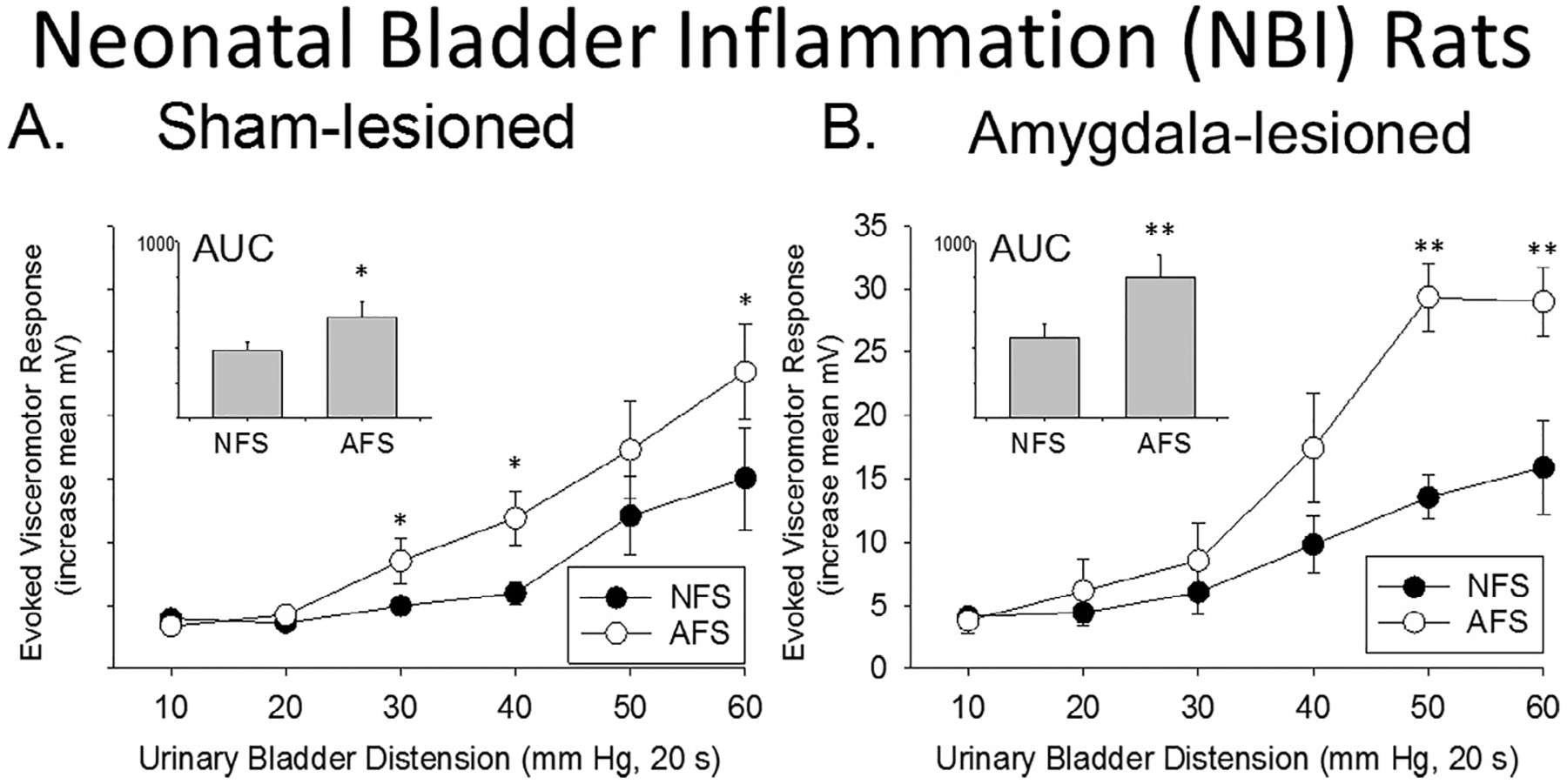

2.3. Acute Footshock produces bladder hypersensitivity in rats which experienced NBI that does not require the central amygdalae

Fig. 3 shows results obtained in rats which had experienced NBI. In the AUC analyses shown in the inset of Fig. 3A, the mean AUC of rats which experienced NBI, the Sham Lesion procedure, and subsequent exposure to Acute Footshock was significantly greater than that of the mean AUC of rats which experienced NBI, the Sham Lesion procedure and the No Footshock protocol (p = 0.035). A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing the individual pressure data, indicated a significant Acute Footshock vs No Footshock effect (p = 0.035) (Fig. 3A). In these rats, there was also a significant effect of distending pressure (p < 0.001), but no interaction between pressure and group. Post-hoc contrasts at each pressure revealed significant differences between the Acute Footshock vs No Footshock groups at 30, 40 and 60 mmHg of distending pressures. These analyses indicate that Acute Footshock effects are present in Sham Lesioned rats which have experienced NBI.

Fig. 3.

Acute footshock produces bladder hyperalgesia in rats which experienced NBI that does not require the central amygdala. Responses to graded urinary bladder distension (UBD; 10–60 mmHg) in rats which experienced NBI were quantified as Evoked Visceromotor Responses following exposure to No Footshock (NFS) or Acute Footshock (AFS) procedures in rats which had received Sham Lesion procedures (Panel A) or bilateral Amygdala Lesions (Panel B). Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) analyses are shown in the insets. The AFS treatment significantly increased the visceromotor responses to UBD relative to NFS in both the sham lesion rats and in the Amygdala Lesion rats. * and ** indicate AFS data significantly different from corresponding NFS data with P < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively. N = 7–9/group.

In contrast to the Control group data, the AUCs of rats which received NBI and subsequently had central Amygdala Lesions continued to demonstrate statistically significant Acute Footshock effects (p < 0.007; Fig. 3B inset). A repeated-measures ANOVA comparing the individual pressure data revealed no significant overall effect of bilateral Amygdala Lesions, but there was a significant lesion x shock treatment interaction (p < 0.001). Therefore, posthoc contrasts were performed showing significant between groups differences for the Acute Footshock vs No Footshock group comparisons at 50 and 60 mmHg. Together, these results indicate that the amygdalae were not required for the Acute Footshock effect in rats which experienced NBI. Notably, all other AUC comparisons were not statistically significant including a comparison of the AUCs of NBI rats which received Acute Footshock and following previous Sham Lesions versus Amygdala Lesions (p = 0.1482).

2.4. Histology

The center of each lesion site is shown for the Control group in Fig. 4A and for the NBI group in Fig. 4B. A typical example of an amygdala lesion is shown in Fig. 4C demonstrating the size of the lesions. See Section 4.6 for inclusion criteria regarding these lesions.

Fig. 4.

Histology. A&B: Composite figures of central of Amygdala Lesions for Control rats (A) and for NBI rats (B) using templates adapted from (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). C: Typical example of fixed brain tissue stained with cresyl violet; light microscopy was used to determine lesion sites.

3. Discussion

The most important finding of the present paper is that bladder inflammation, when experienced at a critical period of development (in this case, the neonatal period) alters supraspinal central nervous system mechanisms known to modulate subsequent sensation of the bladder. In this particular case, an NBI insult led to the development of hypersensitivity when exposed to Acute Footshock as an adult, even in the absence of the amygdalae. This latter point, that it occurred even in the absence of the amygdalae was surprising since we previously established the amygdalae were necessary for the development of this hypersensitivity in normal adult rats which had experienced no neonatal treatments (Randich et al., 2017). Although multiple changes have been noted to occur in peripheral and spinal tissues following NBI, this is the first study to report on supraspinal alterations in neurological function. It therefore reinforces the need to study supraspinal mechanisms of nociception which, with a few exceptions (Neugebauer 2015) are often ignored in preclinical studies. It thereby serves as a sensitive, although not specific, indicator of change which can be probed more precisely in future studies using more sophisticated neurochemical and gene-modifying technologies.

In the multiple “control” experiments of this study, we performed confirmation of our methods by demonstrating that in “normal” (Control) rats the amygdalae were necessary for the evocation of hypersensitivity by Acute Footshock. Otherwise, the simplest explanation for our findings could have been that we had not performed the experiments correctly in NBI rats. Instead, we are able to stay that these findings demonstrate that an additional mechanism mediating hypersensitivity developes in rats which received the NBI treatment. The altered mechanism of this hypersensitivity is yet-to-be determined, however the presence of a unique mechanism for the development of hypersensitivity is consistent with observations in humans with IC who have altered CNS connectivity and activation in functional MRI studies (Deutsch et al., 2016). Of note, our research group has examined subjects with IC, using quantitative sensory testing and found them to be hypersensitive to bladder distension and other deep tissue stimuli (Ness et al., 2005; Lai et al., 2014). A subsequent study in IC subjects (Ness et al., 2014b) suggested that a component of this hypersensitivity was due to the lack of a feedback inhibitory control system that is normally observed in non-IC subjects and activated by a painful conditioning stimulus administered to a heterosegmental site (Conditioned Pain Modulation; CPM). We reported that not only do IC subjects have a failure of CPM, but they also demonstrate a facilitation of responses when other painful stimuli are presented. Others have demonstrated similar phenomena in subjects with other chronic pain disorders such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular disorder and/or chronic tension headaches (Kosek and Hansson, 1997; Lautenbacher and Rollman, 1997; Sigurdsson and Maixner, 1994; Wilder-Smith et al., 2004) – all disorders associated with hypersensitivity and with exacerbation by stress. Development of new or redundant stress-activated pro-nociceptive systems due to alterations in central nervous system structures by developmental factors would explain these clinical observations and be consistent with the observations of the present study.

An organism’s response to stress is thought to be generated by a network of integrated brain structures, in particular the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, the amygdalae, and the periaqueductal gray (Mayer, 2000). These integrated networks are activated in response to various stressors and their output initiates responses within the HPA axis, sympatho-adrenal axis, locus coeruleusnoradrenergic system, and other endogenous pain modulatory systems (Valentino et al., 2011). Our studies have focused on the central amygdalae because they receive nociceptive information via direct spinoamygdalar projections and via an indirect spinoparabrachial pathway, purported to be involved in visceral pain (Bernard et al., 1994; Burstein and Potrebic, 1993; Gauriau and Bernard, 2002) and because of its known connectivity with physiological stress response systems and to known pain modulatory regions. That is, the central amygdalae are in positions suitable for normally mediating the reciprocal relationship between pain and affective processes, and attaching emotional valence to sensory stimuli (Gauriau and Bernard, 2002; Price, 2002).

In the present studies, Acute Footshock produced bladder hypersensitivity to distension in Control animals, similar to data reported previously in studies from our laboratory involving adult rats which experienced no neonatal treatments (Randich et al., 2017). However, since bilateral lesions of the central amygdala failed to eliminated the hypersensitivity resulting from acute footshock in our “altered” animals which experienced NBI, it will be important to determine what nervous system site(s) were responsible for making the amygdalae less important in the development of hypersensitivity to stress. It is possible that another structure(s), such as the parabrachial nucleus, or the ventromedial medulla set a new “tone” for sensory neurons in typical pain pathways (Roeder et al., 2016). The ventromedial medulla has been demonstrated by us to be involved in the hypersensitivity produced by acute footshock in otherwise naïve rats (Randich et al., 2017) and so is a particularly good candidate site. The result of other central nervous system site involvement, in rats which experienced NBI, is that Acute Footshock may cause a transformation of these substrates, perhaps due to changes resulting from the individual rat’s emotional state and cognitive factors relating to chronicity of other bladder symptoms. It was notable that in the absence of a stressor (the No Footshock condition data presented in Fig. 1), there were no significant differences in the responsiveness of the groups. However, when one compares the data from rats that were acutely stressed with unstressed rats, then robust augmentation of responses in NBI rats that had Amygdala Lesions becomes even more manifest suggesting the potential for inhibitory effects arising from the amygdala in NBI rats when intact that disappears with lesioning. All-in-all, these additional augmentation mechanisms may account for difficulties in treating chronic visceral disorders since data obtained by acute manipulations in otherwise healthy animals may not be relevant to those in which pathology is present.

Another site that is likely changed by NBI is the spinal cord itself. Previous studies of spinal dorsal horn neurons excited by urinary bladder distension (Robbins et al., 2011) observed that alterations in a neuronal subpopulation which are produced by acute footshock are abolished with acute spinal transection, but other, similar, studies have demonstrated that changes due to NBI following a rechallenge with bladder inflammation, persist in spinally transected rats (Ness and Randich, 2010).

Finally, in previous studies we showed that NBI produced bladder hypersensitivity when the adult treatment also involved bladder inflammation, a within “visceral” treatment effect (Randich et al, 2006). An important finding of the present experiments is that adult bladder hypersensitivity can be demonstrated with a different secondary treatment, footshock. In the present case, the effects may have more relevant translational importance that mirrors a likely scenario in IC patients, e.g., bladder infection as a neonate might predispose an individual to the development of bladder hypersensitivity when exposed to an adult stressor.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated a critical role for the amygdala in bladder hypersensitivity produced by Acute Footshock but only in otherwise healthy rats. It is not needed when rats have experienced NBI, consistent with an “altered” nervous system.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

Timed-pregnant female Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Harlan (Prattville, AL) and maintained in separate cages. Date of birth was identified and pups treated as indicated in Section 4.2. Rat pups remained housed with their mothers during neonatal treatments and were weaned from their mothers at approximately four weeks of age and raised to adulthood in groups. All rats were housed with food and water available on an ad libitum basis. A 12:12-h light:dark cycle was maintained, where lights were off between 6:00 pm and 6:00 am. There was no attempt to control for estrous cycle in adult rats, as the focus of this study was not on estrous-related changes in pain, and we have previously shown that hormone fluctuations due to the estrous cycle do not alter the vigor of urinary bladder distension-evoked visceromotor responses in rats without bladder inflammation when the current methodology is employed (Ball et al., 2010). These studies were approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham institutional animal care and use committee (IACUC).

Three different pretreatments were performed prior to a final terminal experiment. These pretreatments differed between rat groups and consisted of an early-in-life procedure, a lesion related procedure and a footshock procedure. Each is described below in Sections 4.2–4.4 and the manuscript follows a convention of using capitalization of procedure labels to indicate the broader set of actions performed (e.g. No Footshock actually represents 7 sessions of pretreatment). Fig. 5 has a summary of the Timeline of these experiments.

Fig. 5.

Timeline of experiment.

4.2. Early-In-Life Procedures

Groups of female rats were given an early-in-life treatment beginning at post-natal day 14 (P14). Neonatal Bladder Inflammation (NBI) rats were initially anesthetized with isoflurane (3–5%) delivered by mask and had a 24 gauge intravesical catheter placed trans-urethrally. A 1% zymosan (0.1 ml) solution was then instilled intravesically and the solution was left in place for 30 min while the rats continued to be anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (1–2%) delivered by mask. The bladder then was drained, the catheter removed, and the rat permitted to recover. All rats were kept on a warmed heating pad during treatments and received ampicillin (50 mg/kg s.c.) at the end of each treatment. Control rats received all of the same treatments (anesthesia for 30 min, handling, ampicillin) but were not catheterized and did not have zymosan infused into their bladders. All groups received 3 successive daily treatments on P14–P16 and then raised to adulthood.

4.3. Stereotaxic surgical procedures for bilateral Amygdala Lesions

Rats received stereotaxic procedures at 12 weeks of age. Rats were administered carprofen (5 mg/kg s.c.) one day prior to surgery, on the day of surgery, and one day after surgery. Ampicillin (50 mg/kg s.c.) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg s.c.) were administered the day of surgery. All rats were anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane (2–5%) in oxygen. Hair along the dorsal surface of the head was clipped and the skin surrounding the surgical area was swabbed with a 70% alcohol and povidone-iodine solution. The rat was then secured in a stereotaxic apparatus. Bilateral central Amygdala Lesions were made with using a midline skin incision along the top of the skull and extending approximately 2 cm caudally. A flat-skull orientation was set using bregma as a landmark. A 2.0 mm burr attached to a Dremel device was used to drill holes in the skull. The lesion electrode was constructed of a 00 insect pin insulated to within 1.0 mm of the tip with epoxy. Stereotaxic coordinates for lesions were 2.5 mm posterior to bregma, 4.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 6.8 mm ventral to the brain surface (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). The tip was targeted at the central nucleus of the amygdala but lesions usually encompassed more of the amygdala although normally sparing the basolateral nuclei. Lesions were produced by passage of anodal 1.0 mA direct current for 10 s.

The Sham Lesion control procedure involved drilling burr holes in the skull but no electrode was passed into the brain. Two holes were drilled for comparison with the bilateral Amygdala Lesions condition. The skin incision was closed and animals returned to their home cage to recover from the procedure for seven days.

4.4. Acute Footshock and No Footshock procedures

Acute Footshock was administered in an operant conditioning chamber enclosed in a sound-attenuating chamber similar to our previous studies. In all experiments, Acute Footshock and No Footshock accommodation procedures did not start until a minimum of seven days after recovering from stereotaxic surgery. The accommodation sessions were implemented to reduce stress-related variability due to handling. Each rat was placed in an operant conditioning chamber for a 15 min accommodation session once to twice daily for a total of six sessions prior to final testing. On the day of final testing, Acute Footshock rats were placed in the operant conditioning chamber and received intermittent footshock (15 min, 1.0 mA, 1 s duration, total of 30 shocks) administered via a parallel rod floor on a variable-interval schedule. This procedure has been used previously in our laboratories and demonstrated to produce robust stress-related effects (Robbins and Ness, 2008; DeBerry et al., 2015). No Footshock rats were placed in the operant conditioning chamber but no shocks presented. Rats received the Section 4.5 procedures immediately following withdrawal from the chamber.

4.5. Urinary bladder distension and visceromotor procedures

Four groups of NBI rats and four groups of Control rats were established. Two subsets of each early-in-life treatment groups had Amygdala Lesions and two subsets of each group received Sham Lesion control surgery. The resultant groups were then sub-divided further and received either Acute Footshock or No Footshock treatments. The result was eight separate pretreatment groups that underwent final testing (visceromotor measures) as described here. These animals were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction, 2–3% maintenance during surgery) in oxygen via a tight-fitting mask and a 22-gauge polytetrafluoroethylene angiocatheter (Johnson and Johnson, Arlington TX) was placed into the bladder via the urethra and held in place by a tight suture around the distal urethral orifice. Platinum or silver wire electrodes were inserted into the external oblique musculature immediately superior to the inguinal ligament for recording of abdominal electromyographic activity. Following surgery, anesthesia was reduced until flexion reflexes were present in the hind limbs but spontaneous escape behaviors were absent (1–1.25% isoflurane). All rats then received a series of urinary bladder distensions.

The primary response measure was the visceromotor response evoked by urinary bladder distension which consisted of phasic, constant pressure distension of the urinary bladder via the intravesical catheter. An in-line, pneumatically-linked, low volume pressure transducer was used to monitor intravesical pressure. Pressure within the bladder during stimuli was controlled using a pressure control device similar to previous reports (e.g., Randich et al., 2017). In the various treatment groups, approximately 15 min after initial anesthesia induction, three or more 60 mmHg distensions (3 min inter-trial interval) were administered to establish stable responses and were followed by graded, constant-pressure air distensions of the urinary bladder (20 s duration; 3 min inter-trial interval) of ascending pressures at intervals of 10 mmHg up to 60 mmHg. Contraction of the abdominal musculature, recorded as electromyographic activity, was measured via the electrodes using standard differential amplification and rectification and saved on a computer (Spike 2 software, Cambridge Electronic Design, UK). Electromyographic responses were quantified as rectified mean myoelectrical activity measured during urinary bladder distension minus rectified mean baseline myoelectrical activity measured for 10 s prior to urinary bladder distension and expressed as the Evoked Visceromotor Response.

4.6. Histology

Upon completion of the experiments, brain tissue was extracted, placed in fixative, processed, sliced into 40 lm sections and stained with cresyl violet. Light microscopy was used to verify lesion sites. Sections were matched to a range of templates (−2.12 to −2.56; derived from (Paxinos and Watson, 1986)). For the lesions to be considered successful, it was required that 90% of both central amygdalae were destroyed or replaced by gliosis in at least two of the sections on each side.

4.7. Statistical analyses

Statistics are presented as the mean ± S.E.M in the graphs. Two response measures were analyzed: the calculated Evoked Visceromotor Responses for each distension pressure analyzed using a repeated measures ANOVA; and an Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) measure of the plot of these values analyzed using unpaired t-test comparisons. Post-hoc contrasts using Tukey’s HSD were performed at each pressure when appropriate and Holm’s (Holm,1979) procedure maintained family-wise α at 0.05. It is our view, that the AUC measures provide a simpler dependent measure of treatment effects since they collapse all the individual data into a single measure.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by NIDDK DK051413. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Ball CL, Ness TJ, Randich A, 2010. Opioid blockade and inflammation reveal estrous cycle effects on visceromotor reflexes evoked by bladder distention. J. Urol 184, 1529–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard JF, Huang GF, Besson JM, 1994. The parabrachial area: electrophysiological evidence for an involvement in visceral nociceptive responses. J. Neurophysiol 71, 1646–1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birder L, deGroat WC, Mills I, Morrison J, Thor K, Drake M, 2010. Neural control of the lower urinary tract: peripheral and spinal mechanisms. Neurourol. Urodyn 29, 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Berry SH, Clemens JQ, 2007. Symptoms of interstitial cystitis, painful bladder syndrome and similar diseases in women: a systematic review. J. Urol 177, 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein R, Potrebic S, 1993. Retrograde labeling of neurons in the spinal cord that project directly to the amygdala or the orbital cortex in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol 335, 469–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerry J, Ness TJ, Robbins MT, Randich A, 2007. Inflammation-induced enhancement of the visceromotor reflex to urinary bladder distention: modulation by endogenous opioids and the effects of early-in-life experience with bladder inflammation. J. Pain 8, 914–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deberry J, Randich A, Shaffer A, Robbins M, Ness TJ, 2010. Neonatal bladder inflammation produces functional changes and alters neuropeptide content in bladders of adult female rats. J. Pain 11, 247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerry J, Robbins MT, Ness TJ, 2015. The amygdala central nucleus is required for acute stress-induced bladder hyperalgesia in a rat visceral pain model. Brain Res. 1606, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch G, Despande H, Froelich MA, Lai HH, Ness TJ, 2016. Bladder distention increases blood flow in pain related brain structures in subjects with interstitial cystitis. J. Urol 196, 902–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauriau C, Bernard J-F, 2002. Pain pathways and parabrachial circuits in the rat. Exp. Physiol 87, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S, 1979. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stats 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kannampalli P, Babygirija R, Zhang J, Poe MM, Li G, Cook JM, Shaker R, Banerjee B, Sengupta JN, 2017. Neonatal bladder inflammation induces long-term visceral pain and altered responses of spinal neurons in adult rats. Neuroscience 346, 349–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosek E, Hansson P, 1997. Modulatory influence on somatosensory perception from vibration and heterotopic noxious conditioning stimulation (HNCS) in fibromyalgia patients and healthy subjects. Pain 70, 41–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai HH, Gardner V, Ness TJ, Gereau RW 4th, 2014. Segmental hyperalgesia to mechanical stimulus in interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome: evidence of central sensitization. J. Urol 191, 1294–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbacher S, Rollman G, 1997. Possible deficiencies of pain modulation in fibromyalgia. Clin. J. Pain 13, 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee UJ et al. , 2015. Chronic psychological stress in high anxiety rats induces sustained bladder hyperalgesia. Physiol. Behav 139, 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovick TA, 2016. Central control of visceral pain and urinary tract function. Auton. Neurosci 200, 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK et al. , 2004. Autonomic response to stress in interstitial cystitis. J. Urol 172, 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutgendorf SK, Kreder KJ, Rothrock NE, Ratliff TL, Zimmerman B, 2000. Stress and symptomatology in patients with interstitial cystitis: a laboratory stress model. J. Urol 164, 1265–1269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer EA, 2000. The neurobiology of stress and gastrointestinal disease. Gut 47, 861–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Kampe MH, DeWitte CR, Randich A and Robbins MT. 2014. Early-in-life bladder inflammation results in clinical features of interstitial cystitis. Society for Neurocience Meeting 2014, abst.#11596., 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Powell-Boone T, Cannon R, et al. , 2005. Psychophysical evidence of hypersensitivity in subjects with interstitial cystitis. J. Urol 173 (1983–1987), 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Randich A, 2010. Neonatal bladder inflammation alters activity of adult rat spinal visceral nociceptive neurons. Neurosci. Lett 472, 210–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ness TJ, Lloyd LK, Fillingim RB, 2014a. An endogenous pain control system is altered in subjects with interstitial cystitis. J. Urol 191, 364–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugebauer V, 2015. Chapter 15: Amygdala pain mechanisms. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol 227, 261–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C, 1986. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Peters KM, Killinger KA, Ibrahim IA, 2009. Childhood symptoms and events in worment with interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome. Urology 73, 258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD, 2002. Central neural mechanisms that interrelate sensory and affective dimensions of pain. Mol. Interv 2, 392–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randich A, Uzzell TW, DeBerry JJ, Ness TJ, 2006. Neonatal urinary bladder inflammation produces adult bladder hypersensitivity. J. Pain 7, 469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randich A, Mebane H, Ness TJ, 2009. Ice water testing reveals hypersensitivity in adult rats that experienced neonatal bladder inflammation: implications for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis. J. Urol 182, 337–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randich A, DeWitte C, DeBerry JJ, Robbins MT, Ness TJ, 2017. Lesions of the central amygdala and ventromedial medulla reduce bladder hypersensitivity produced by acute but not chronic foot shock. Brain Res. 1675, 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MT, DeBerry J, Ness TJ, 2007. Chronic psychological stress enhances nociceptive processing in the urinary bladder in high-anxiety rats. Physiol. Behav 91, 544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MT, Deberry J, Randich A, Ness TJ, 2011. Footshock stress differentially affects responses of two subpopulations of spinal dorsal horn neurons to urinary bladder distension in rats. Brain Res. 1386, 118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MT, Ness TJ, 2008. Footshock-induced urinary bladder hypersensitivity: role of spinal corticotropin-releasing factor receptors. J. Pain 9, 991–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder Z et al. , 2016. Parabrachial complex links pain transmission to descending pain modulation. Pain 157, 2697–2708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothrock NE, Lutgendorf SK, Kreder KJ, Ratliff T, Zimmerman B, 2001. Stress and symptoms in patients with interstitial cystitis: a life stress model. Urology 57, 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta JN, Pochiraju S, Kannampalli P, Bruckert M, Addya S, Yadav P, Miranda A, Shaker R, Banerjee B, 2013. MicroRNA-mediated GABA Aa-1 receptor subunit down-regulation in adult spinal cord following neonatal cystitis-induced chronic visceral pain in rats. Pain 154, 66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AD, Ball CL, Robbins MT, Ness TJ, Randich A, 2011. Effects of acute adult and early-in-life bladder inflammation on bladder neuropeptides in adult female rats. BMC Urol. 11 (18), 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AD, Ness TJ, Robbins MT, Randich A, 2013a. Early in life bladder inflammation alters opioid peptide content in the spinal cord and bladder of adult female rats. J. Urol 189, 352–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer AD, Ness TJ, Randich A, 2013b. Early-in-life bladder inflammation alters U50,488H but not morphine-induced inhibition of visceromotor responses to urinary bladder distension. Neurosci. Lett 534, 150–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson A, Maixner W, 1994. Effects of experimental and clinical noxious counterirritants on pain perception. Pain 57, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AL et al. , 2011. The effects of acute and chronic psychological stress on bladder function in a rodent model. J. Urol 78, 967.e1–967.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino et al. , 2011. The bladder-brain connection: putative role of corticotropin-releasing factor. Nat. Rev. Urol 8, 19–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith CH, Schindler D, Lovblad K, Redmond SM, Nirkko A, 2004. Brain functional magnetic resonance imaging of rectal pain and activation of endogenous inhibitory mechanisms in irritable bowel syndrome patient subgroups and healthy controls. Gut 53, 1553–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Yu J, Kannampalli P, Nie L, Meng H, Medda BK, Shaker R, Sengupta JN, Banerjee B, 2017. MicroRNA-mediated downregulation of potassium chloride cotransporter and vesicular gABA transporter expression in spinal cord contributes to neonatal cystitis-induced visceral pain in rats. Pain 158, 2461–2474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]