Abstract

Introduction: Chilean policy makers reformed the national health policy for primary health care (PHC), shifting from the traditional biomedical model to the integral family and community health model with a biopsychosocial approach, to guide the delivery of PHC throughout the country. Purpose: To evaluate the implementation of the national health policy for PHC through an analysis of the program documents for PHC; and to identify to what extent the national health policy is expressed in each program document, and across all the documents. Methods: A qualitative document analysis with a purposive sample of program documents for PHC. The Chilean Ministry of Health website was systematically searched between October and December 2018 to identify relevant program documents. Thematic and content analysis were performed to identify evidence of the biopsychosocial approach to care delivery with each program document, including the types of interactions between professionals that contribute to person-centered or fragmented care. Results: The study included 13 PHC program documents. Three themes and 10 categories emerged from the data. Most program justifications focused on the biopsychosocial approach to care while including biomedical interventions and supporting independent professional work. Only 4 of the 13 programs were consistent in the justification, interventions, and types of stated professional interactions: 2 from the biopsychosocial and 2 from the biomedical perspectives. Conclusion: In terms of the national health policy for PHC in Chile, interprofessional collaboration and person-centered care processes and practices were partially aligned with the written content of the health program documents. As such, policy makers and health sector leaders are advised to analyze draft health program documents for consistency in translating national health policies into the written communications that define the actualization of the care model in PHC and direct professionals how to provide PHC to individuals and families.

Keywords: Chile, public health, primary care, health policy, health programs, biomedical, biopsychosocial, interprofessional collaboration, person-centered care, qualitative method, document analysis

Introduction

For decades, public health leaders have attempted to develop health systems focused on providing universal access to cost-effective person-centered primary health care (PHC), generally regarded as the most efficient and effective model for solving national health problems.1,2 Primary care teams (PCTs) are essential to provide the evidence-based, community-delivered, and person-centered care1 to achieve population health objectives such as reduced morbidity and mortality, decreased chronical disease prevalence, and improved child and maternal outcomes.1,3-5 Ideally, these teams can provide the first and continued access point for comprehensive primary health care with coordinated interventions. Person-centeredness is an essential strategy to holistically conceptualize health care, including evaluating wellness and diagnosing sickness considering the patient perspective.6 As such, PCTs can provide robust person-centered care,1,7 guided by the biopsychosocial model,8 understanding the biological, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual interactions in an egalitarian way.7,9,10

The national health policy for primary care has shifted to the biopsychosocial perspective11 principally focused on providing person-centered care delivered by teams12,13 in primary health settings. This contemporary approach is more robust than the previous biomedical model where dysfunctional systems and diseased organs are contextualized as biochemical and mechanical disorders.9,10,14 The national health policy is implemented into practice through the primary health care programs. Developing these programs requires bringing together a diverse group of professionals working together as a PCT. There need to be organizational guidelines, as well as conditions (eg, team meetings, shared spaces, integrated health records) to facilitate knowledge exchanges, to improve communication about care, to construct a shared perspective about collaboration, and to coordinate care management.15-17 Thus, the new model selected to guide the national health policy needs to be explicitly written into the health program documents in order to achieve the expected actions that result in achieving the national primary health care outcomes.18,19

When the national health programs are focused on person-centered approaches to providing care, the different professions can work together, or collaborate, as a PCT to provide more efficient and cost-effective health services20-22 as compared to the inefficient and fragmented care observed with disease-centered approaches.23-26 In this regard, collaboration is the sum of professional interactions characterized by mutual goals and values, aligned responsibilities, distributed power, shared decision making, effective communication, and interdependent roles with a shared identity.15,27-30 The enactment of policies, procedures, processes, and practices that support collaborative work environment, specially interprofessional collaboration27,28,30 has been identified as a facilitator24,30; hence the reason many countries have implemented reforms that foster collaborative work.23,24,27,31,32

Historical Context

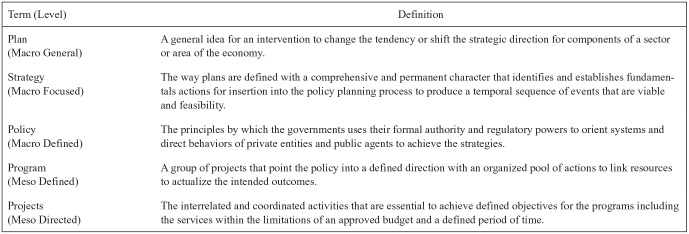

The current Chilean PHC system, funded by the national government and managed by the municipalities,33-35 provides health services to nearly 80% of the population principally the low-income population.36,37 The PHC provide basic benefits, usually bundled within health programs, as part of the Family Health Plan (Plan de Salud Familiar in Spanish).12 The health programs guide the provision of health services throughout the life span with health promotion, prevention, diagnostic, treatment, and rehabilitation interventions implemented by the Regional Ministerial Secretaries in the PHC centers.12,38 The interventions extended from these primary care programs are supposed to be synergistic with the activities at the other levels of the system, including secondary and tertiary. The programs include public health activities ranging from vaccinations to palliative care. Figure 1 provides an overview, with definitions, of the basic hierarchical structures involved in government planning for interventions in the health sector.

Figure 1.

Hierarchy of terminology for national health planning in Chile.

Note: For the Chilean health sector, the government generates documents to actualize the planning process into health programs. The terms with definitions for the levels are translated for clarity of meaning (Reference: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/7316).

Historically, the Chilean Ministry of Health (MOH) has made efforts to solve problems in the national health sector with strategies conceptualized from a biopsychosocial perspective.11 As such, in 1993 the MOH began revising the national health policy with reforms to the structural framework and organizational processes for delivering PHC.11 With the purpose to achieve a deeper knowledge about the health of the population, a process called “sectorization” divided the health center populations, by geographical reference, into smaller more localized areas to be managed by multidisciplinary PCTs11; called empanelment in the international literature.22,25,39 In the past, the PCTs were organized via programs and projects, to address the health and wellness of people, families, and communities. Through the revision to the PHC model, the MOH saw the need to include multiple professionals working in teams to provide better primary care.11 The synergy generated by the multidisciplinary teams working in a collaborative and coordinated manner was expected to address the growing complexity of the national health problems.11

Between 2008 and 2009, the MOH advanced the model to guide to PHC delivery40,41 to the Integral Family and Community Health Model (IFCHM), an extension of the Engel Biopsychosocial Model40; used from 1993 until the present.11 The resulting policies addressed the challenges associated with implementing the original model by shifting the focus from the traditional disease-centered to family-centered care. Within this context, a 5-stage transformational process (1—Etapa Consultorio [Organization of Work]; 2—Motivation and Commitment; 3—Development; 4—Strengthening; 5—Consolidation) was implemented through organizational guidelines that facilitated family-centered care.40,41 As a result, the organizational guidelines redirected the PHCs to support multidisciplinary teams40,41 to provide transdisciplinary care,40,41 or interprofessional collaboration. The health policies focused on developing organizational guidelines that support interactions, based on communication, trust, synergy, interdependency, encourage respect for different roles, and support professional autonomy12,40,41 resembling closely to what is internationally called interprofessional collaboration3,18,19,27,42; the perspective strengthened in the 2012 health policy.12 The consolidated model described in 2012 guideline (Orientaciones para la implementación del modelo de atención integral de salud familiar y comunitaria) guides the care in every PHC facility across Chile.41

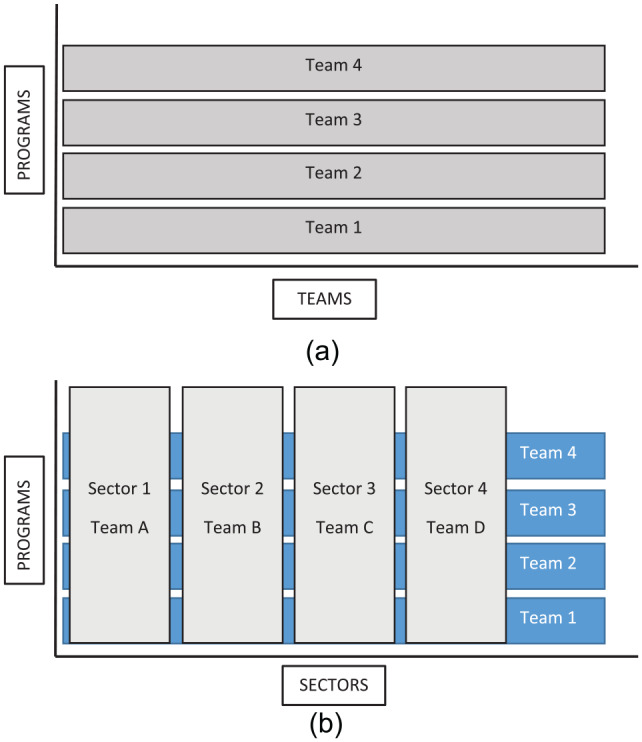

Throughout the model development and refinement process to actualize the new primary care strategy, the MOH developed new technical standards and clinical guidelines for the PHC program related activities.35 These changes captured the contemporary perspective for managing health, including consideration for the social determinants of health. Importantly, most programs originated prior to the IFCHM; subsequently updated over the last decade.35 With updates to the programs, professionals are directed to work differently within teams across the PHC system.43 The matrix organization44,45 was initially developed in 1993, refer to Figure 2, to achieve the program and sectoral/territorial goals.11,12,40,41

Figure 2.

Organizational structures of programs and teams. (a) Program structures and teams without sectors prior to 1993. (b) Program structures and teams with sectors after 1993.

Purpose

The Chilean policy makers shifted the national health policy from the traditional biomedical to the contemporary biopsychosocial approach to guide how health services are delivered throughout the country. The purpose of this study was to analyze the content of the national health program documents for primary care (produced by the MOH) to evaluate their alignment with the national health policy. In particular, this study sought to evaluation how the national health policy was implemented through the content of the health program documents for primary care, and to what extent are the elements from the national health policy present within each document, and across all the documents that define primary health care in Chile.

Methods

This qualitative study46 applied the method called document analysis47 to evaluate the influence of national health policies on the delivery of primary health care through the thematic analysis of the associated health program documents. These program documents formally communicate the health policy through written directives to guide primary health care professionals. Although this qualitative method is flexible, reflective, subjective, and iterative,48 the resulting data analysis is credible, dependable, confirmable, and transferable49 as rigor50 and trustworthiness51 are a fundamental objective. The document analysis method for this study is described in the next section, followed by an overview of the 5 phases of the research process.

Document Analysis

Although “qualitative research is many things to many people,”52(p8) ethnographic content analysis53 is a traditional qualitative method54 that permits researchers to recruit verbal, visual, and written communication as “participants” for studies to search-out underlying themes in the materials collected for analysis. In the qualitative paradigm, there are four major sources of data, including: interviews, focus groups, observations, and written text/audiovisual materials.55 In terms of research using written text, the document analysis method is the most prevalent qualitative approach that is commonly used for public health56 and policy research.57,58 For this study, a health policy document was defined as the textual evidence of policies focused on health with a governmental origin, cultural persuasion, and contextual uniqueness59 that can be recorded and retrieved for description and analysis.60

Document analysis has been defined as “an approach of empirical, methodological controlled analysis of texts within their context of communication, following content analytical rules and step-by-step models, without rash quantification.”61(p5) Similarly, social scientists view the method as “an approach to documents that emphasizes the role of the investigator in the construction of the meaning of and in texts.”62(p285) For the purpose of this specific study, document analysis was defined as a systematic process to review and evaluate health policy documents that requires data to be complied, disassembled, reassembled, and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge.47

Five Phases for Document Analysis

The document analysis was completed in 5 phases: (1) selected the subject of analysis and identifying the documents; (2) defining the search strategy and collecting the targeted documents; (3) scanning the text, coding the data, and organizing the codes; (4) analyzing the codes and identifying the categories; and (5) interpreting the findings and reporting the results.46,63-65 In summary, content analysis reduces data into the categories for calculations and comparisons such as descriptive, normative, cross-sectional, and longitudinal,66 while thematic analysis examines the relationships and meanings within and between the categories to identify themes.67 As such, this study applied thematic and content analysis to move from data, to codes, to categories, and finally to themes, to answer the same research question.68 The 5 phases for this study included

Defining the subject of analysis and identifying the documents. The research question, supported with a theoretical background, resulted in the identification of the Chilean health program documents for analysis. The health program documents are publicly available through the Chilean MOH website. Each program corresponds to a program document that was developed by the MOH, either at the central or regional level, and applied in every PHC in Chile.

Defining the search strategy and collecting the targeted documents. The purposive sample56 of documents for this study was selected from a systematic search69 of publicly accessible official Chilean government websites and databases,70 principally the MOH, between October and December of 2018 with the key terms (in Spanish): Programs, guidelines, technical orientations, programmatic orientations, vital cycle programs, transversal programs, support programs and health.71 Only documents published within the past 10 years, following the health reform, were included in the sample; all other documents were excluded. An additional document verification search was completed at the end of the study, in 2019, to identify potentially missing or important new documents prior to completing the presentation of the results.

Scanning the text, coding the data, and organizing the codes. Once the sample was completed, the documents were reviewed multiple times by the research team for familiarity with the format, content, and context. The paragraph was adopted as the unit of analysis64 for each document. The document review and data collection process focused on identifying and coding the implicit and explicit content evidence, related to the biomedical and biopsychosocial models. In addition, the types of interactions between professionals as well as the relationships that could lead to person-centered or fragmented type care were identified and coded for analysis.

Analyzing the codes and identifying the categories. Following the organization of the relevant paragraphs, and the highlighting of key sentences, these were organized for the thematic and content analysis.72 The analysis process progressed in 10 steps, including (1) review the identified documents; (2) develop the main categories; (3) complete the first coding process; (4) compile the data for each category, look for subcategories; (5) complete the second coding process; (6) category-based analysis; (7) thematic-based analysis; (8) interpret the findings; (9) Review the work, check the notes, and discuss the findings; and (10) organize and prepare the results.65,68,73-76 For developing the codes, a deductive identification process using a “code template” constructed a priori based on the theoretical review.77 Demonstrating the rigor using thematic analysis,74 the process also included an inductive perspective to allow modification and/or expansion of the prior codes or emergence of new codes.

Reporting the results. Through a constant comparison technique,78 data were organized and sorted into different themes for reporting. These themes are described in detail as an evidence of the researcher rationale.65,75 For results presentation, the most representative quotes were selected as exemplars for each code as well as to support the overall analysis.49,74 Furthermore, a summary table was constructed to illustrate the frequency in which the codes were present in each document, defined as absent (0) to very present (+++).46,74 This process permitted the analysis of internal coherence for each document; making possible an evaluation of congruence between each model, biomedical and biopsychosocial, with the health actions and the professional interaction types described within the documents. Then, the final evaluation was completed to review about the alignment of the study concepts within the national health policy.

Trustworthiness

Multiple strategies and techniques were incorporated into the study design to establish the trustworthiness79 of the thematic analysis, including memos, framework coding, audit trails, referential adequacy testing, peer debriefing, and detailed content descriptions for data representation.49,80 Memos81 were maintained throughout the coding and categorization process. The memos provided the previous ideas, insights, and interpretations that aided with the continuously probing of the data and the frequent rechecking of the results.82 In addition, the member debriefings and the peer debriefings provided essential pauses for collective reflection to validate the data representation and the derived meaning.83 As recommended,84 the categories and themes and were not finalized until all the data were reviewed and the codes were scrutinized multiple times.

The data presented in the quotes throughout the analysis are provided in the original Spanish and the translated English versions (see Supplementary Table 1). In addition, the documents are publicly available to review the raw data.74 Finally, the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research85 were followed to improve the transparency for the dissemination of this study, as well as the criteria86 outlined for evidence-based research and practice. As the program documents are available in the public domain, without any type of private or confidential information, an institutional review board approval was not required.

Results

The systematic document search strategy resulted in the inclusion of 13 health program documents (see Table 1) for analysis. In addition, the summary for each health program document included in this study (see Supplementary Table 2). From the analysis, 10 categories emerged from the data and organized into 3 themes (see Table 2). The next sections describe the 3 themes: program justification, interventions considered in the program, and types of professional interactions.

Table 1.

National Health Program Documents for Primary Health Care in Chile.

| No. | Health program documents (English/Spanish) | Publication year |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Integrated health for children / Salud de la infancia con enfoque integral | 2013 |

| 2 | Integrated health of adolescents and young people / Salud integral adolescentes y jóvenes | 2012 |

| 3 | Older adult health / Salud del adulto mayor | 2014 |

| 4 | Cardiovascular health / Salud cardiovascular | 2017 |

| 5 | Complementary nutrition for children and adults / Alimentación complementaria del niño y del adulto | 2011 |

| 6 | Sexual and reproductive health / Salud sexual y reproductiva | 2017 |

| 7 | Mental health in primary care / Salud mental en atención primaria | 2013 |

| 8 | Home health services for patients with severe dependence / Cuidadores de pacientes por dependencia severa | 2014 |

| 9 | Integrated rehabilitation in the health network / Rehabilitación integral en la red de salud | 2014 |

| 10 | Integrated dental care / Odontológico integral | 2018 |

| 11 | Respiratory heath / Salud respiratoria | 2015 |

| 12 | Self-sufficient older adults / Más adultos mayores autovalentes | 2015 |

| 13 | Healthy lifestyle / Vida sana | 2015 |

Table 2.

Themes and Categories.

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| Program justifications | Biomedical definition of the problem |

| Biopsychosocial definition of the problem | |

| Biomedical solution proposed for the identified problem | |

| Biopsychosocial solution proposed for the identified problem | |

| Program interventions | Person-centered intervention |

| Fragmented intervention | |

| Types of interactions between disciplines | Intersectoral work |

| Interprofessional work | |

| Multiprofessional | |

| Uniprofessional work |

Program Justification

The definition for the health problem and the solutions were addressed by each program through interventions. From these 2 components, the health policies were configured with the justification, or background, for the associated program. In defining the health problem addressed in the health policies, elements of both the biomedical and biopsychosocial perspectives were identified. However, the majority of programs, 10 of the 13,87-96 primarily embraced the biomedical perspective. In this regard, they emphasized objective data using statistical and epidemiological measures, generally derived from national epidemiological surveys, to quantified sickness as the central principle that underlies the creation and maintenance of the program.

The National Health Survey (2009-2010) permits a baseline for this proposal (. . .) a complex situation exists for the Chilean population in some areas of health, such as a high prevalence of chronic noncommunicable diseases, which are acquired in the period of adolescence and youth, causing morbidity or mortality during adulthood. (Integrated health for adolescents and youth, p. 8)

In the case of the biopsychosocial approach, 11 programs,87-94,96-99 partially defined the health problem using the social determinants of health framework to understand the context and to acknowledge the interactions between the factors, including family relationships, socio-cultural characteristics, environmental situations, and economic conditions. Also, gender, migration, and life course were considered.

The development of all childhood deficiencies is related to several variables, such as mother and father parenting skills, access to preschool, disease prevention strategies and health promotion, environmental conditions, socioeconomic and cultural characteristics in which the child develops, etc. (Integrated health for children, p. 37)

In terms of the proposed solutions, both the biomedical and biopsychosocial perspectives were identified within the data. In the case of the biomedical perspective, seven programs,87-89,91,93,95,96 focused on identifying people at risk for the disease, incorporating interventions to address pathophysiologic conditions, and prioritizing health services to address the risk and/or disease severity.

The program focuses on those people who have a high risk for developing hypertension and type 2 diabetes in the future (. . .) there are screening tests that can identify high risk subjects, as well as safe and potentially effective interventions that may decrease the risk factors for developing noncommunicable diseases. (Healthy lifestyle, p. 6)

Regarding solutions from a biopsychosocial perspective, the focus was to address inequalities during critical development periods for people, an example is the national health program that focused on promoting the integrated development of children87 by improving the environment in which they grow and develop.

In 2008, the Comprehensive Early Childhood Protection System was implemented at the national level (. . .) This system is an integrated management model which includes different government agencies, seeking to deliver differentiated conditions for families in order to reduce inequality in the most critical period of development, from gestation to 4 years old. (Integrated health for children, p. 22)

Programs also considered interventions based on the social determinants of health framework, as well as the ecological, cognitive behavioral, and learning models. Ten documents analyzed include solutions with a holistic orientation87,89-91,93-97,99 In general, the predominant perspective implied in the proposed solutions were conceptualized from the biopsychosocial model.

Interventions Considered in the Program

The interventions correspond to the actions stated in the programmatic guidelines or programs applied by professionals. The existence of fragmented and person-centered interventions was identified. For example, a classic biomedical/fragmented intervention was related to the diagnosis and treatment of a pathology, with specific actions to manage the acute disease period with periodical medical controls. In this case, the interventions focused on managing symptoms that compromise health status and thus, decrease the perceived quality of life, not necessarily based on the actual experience of having a disease, but rather using preconceived instruments that defines the way to understand quality of life.

Diagnosis and treatment (. . .) evaluation, confirmatory diagnosis, categorization, treatment and follow-up for recurrent obstructive bronchial syndrome, bronchial asthma and other chronic respiratory conditions; periodic visits for chronic respiratory patients with standards and evaluation to control levels; evaluation of quality of life for patients entering the program for acute respiratory infections, with standardized instrument. (Respiratory heath, p. 17).

Additionally, person-centered interventions were identified. An example is how the integral home visits were included in several programs to be in closer contact with the person, within the context of their home and surrounding community, to understand their reality. This provides a wider assessment of the environmental context in which the person lives, expanding from the biological to the psychological and social aspects of their health status.

The integrated health services provided in the home focus on high risk groups, considering the family environment through the actions of promotion, protection, recovery, and rehabilitation of health (. . .) allows an interaction with one or more family members, with the caregiver, and the environment; tending to achieve better knowledge and support to confront the bio-psycho-social-hygiene problems. . . . (Home health services for patients with severe dependence, p. 6)

Both interventions were identified in all the health programs,87-99 principally with more fragmented interventions in the analyzed documents.

Types of Interaction Between Professionals

In this study, there were interventions supporting different types of interactions that impacted how professionals worked resulting in different levels of collaboration with the patient. The documents describe 4 types of work in terms of these interactions, including (1) intersectoral work (developed with other governmental sectors), (2) interprofessional work (developed in a collaborative way that include different professionals), (3) multiprofessional work (developed independently but in a coordinated way), and (4) uniprofessional work (independent work). In the first case, the different sectors need not only coordinate care, they also needed to plan together with a common goal focused on improving the actual health status of the person, encouraging health coverage, and providing care within the context of the community. This type of work was included in 12 programs.87-93,95,97,99

Working with older adult clubs and office programs related to sports and other education, cultural, and social activities (. . .) can increase the coverage and the proximity of the health team with the community. (Self-sufficient older adults, p.10)

The interprofessional work was observed in 5 programs.87,93-95,97

It will be developed in the community, with the action of the Primary Health Care Team, in particular, with a double Physical-Occupational Therapist or another trained professional. (Self-sufficient older adults, p. 8)

Also, multiprofessional work was described in the documents through teamwork, team leaders (equipo de cabecera in Spanish), and/or specialty teams. When the documents indicated clinicians can manage care, either alone or with other colleagues, the interactions were not mandatory. This type of work was included in 9 programs.87-91,93,96-98

One of the actions that must be carried out by the Health Care Team, corresponds to the integrated home visit (. . .) through promotion, protection, recovery, and rehabilitation of health actions that one or more members of the Health Care Team performs at the home of the family or user. (Home health services for patients with severe dependence, p. 7)

When activities related to care were independently performed by specific professionals, these were labeled uniprofessional work. There was a tendency in program documents for multiple interventions that could be performed by several professionals, but were stated to be completed one-to-one manner, usually in an examination/treatment room. Ten programs included this type of uniprofessional interventions throughout the program.87-88,90-93,95,97-99

Reception in the Acute Respiratory Diseases patient area referred from the health network due to an acute respiratory or exacerbation of a chronic respiratory condition, to access a visit with the physical therapist within the deadlines established Explicit Health Guarantees for patients. (Respiratory health, p. 20)

A summary of the findings is organized in Table 3. In general, we observed a predominance of biopsychosocial characteristics for the program justification, as well as fragmented interventions and uniprofessional work. Regarding the alignment between person-centeredness and interprofessional collaboration in the program documents published by the MOH, we only found 2 aligned programs, including the “self-sufficient older adults”94 and a partial alignment in “mental health”97 programs. However, we found an alignment between the biomedical model with fragmented interventions thru independent or coordinated professional work in the cases of the “respiratory health”92 and “rehabilitation health”91 programs. We also observed a balance between the 2 perspectives with all professional interactions in the “integrated health for children”87 and “healthy living”93 programs. Throughout the other programs, we were unable to identify a clear profile. We should also note that only the “integrated health for children”87 and “healthy living”93 programs explicitly included the IFCHM within its background, being exposed but not narratively integrated into the different components of the program.

Table 3.

Summary of the Results by Health Program.a

| Justification of the program |

Interventions considered in the program |

Type of interaction between professionals |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical definition of the problem | Biopsychosocial definition of the problem | Biomedical solutions | Biopsychosocial solutions | Fragmented | Person-centered | Intersectoral work | Interprofessional work | Multiprofessional work | Uniprofessional work | |

| Children health with integrated approach | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Integrated health of children and adolescents | + | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | + | + |

| Older adult health | ++ | ++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | + | 0 | + | 0 |

| Mental health in primary care | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | + |

| Home services for patients with severe dependence | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | + | + |

| Integral rehabilitation in the health network | ++ | + | + | + | ++ | + | + | 0 | + | + |

| Self-sufficient older adults | + | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular health | + | 0 | + | + | ++ | + | + | + | 0 | + |

| Complementary feeding of children and adults | + | + | + | + | ++ | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

| Sexual and reproductive health | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | 0 | + | ++ |

| Integral dental | 0 | + | 0 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | ++ |

| Respiratory health | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | +++ | + | + | 0 | 0 | +++ |

| Healthy lifestyle | + | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | + | + | + | + |

0 = absent (0%); + = present (until 25%); ++ = medium presence (until 55%); +++ = very present (55% or more).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to analyze the alignment between the Chilean national health policy related to the biopsychosocial model, as manifested through person-centered care and interprofessional collaboration, and the current health program documents developed by the MOH. Overall, the program justifications generally referenced the biopsychosocial model with biomedical interventions performed with independent professional work. Six programs were consistent in their justification, interventions, and type of expected professional interactions, including 2 with a biopsychosocial orientation, 2 with a biomedical orientation, and 2 with a mixed orientation.

In the context of policymaking, the lens used to define the problem results in different solutions depending on the context analyzed.100 As the IFCHM provides guidelines for the problem definition, proposed solutions, and types of required work, we expected to find a similar perspective in the programs coexisting with the model, especially since all programs were published after 2010 (the years following model implementation). To this point, we expected the health of a person to be defined from a more holistic approach to person-centered care. Instead, we observed the biopsychosocial approach to PHC was not robustly translated into the written program interventions. Instead, the findings were consistent with the interventions resulting in fragmentation historically linked to the biomedical paradigm.14 Furthermore, we found person-centered interventions that were not accompanied by interprofessional work, demonstrating an inconsistent translation of holistic interventions necessitate by the IFCHM. In this sense, less than half the program documents included interprofessional collaboration.

In terms of the alignment between person-centered care and interprofessional collaboration, we only found evidence in 2 programs (“self-sufficient older adults” and “mental health”). Both programs have a health promotion and preventive approach to delivering health services to a well-defined population. Promotion and prevention activities require a broad vision, for example, in the case of promoting healthy lifestyle there need to be recommendations related to nutrition, physical activity, stress management, and self-care. In this regard, the team needs to include different professionals such as dietitians, nurses, physical therapists, and psychologists. This situation opens more possibilities for different professionals to collaborate in the care management; eliminating the typical limitation related to the specialized medical knowledge that hinders interprofessional collaboration.30,101 This can also explain why the “respiratory health” and “rehabilitation health” programs have a clear biomedical stamp as both programs are focused on physiological determinate systems that require specialized medical knowledge or practices that can be applied by one profession, in this cases by a physical therapist. On the other hand, some interventions included in “self-sufficient older adults” and “mental health” programs are applied in group sessions, which usually requires more than one professional to manage the group. Furthermore, many of the interventions occur in community settings; identified as a facilitator of interprofessional collaboration.30 Finally, every program analyzed included person-centered interventions but only 5 program descriptions included activities performed in a collaborative way by 2 or more professionals.

Contrasting the previous Chilean context, the highly developed countries such as the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom have implemented health policy reforms supporting interprofessional collaboration through patient-centered care in the medical home context.30,102,103 Interprofessional collaboration is viewed as a component of patient-centered care, especially with complex cases that require a broader perspective to plan multiple strategies to tackle the health problems.102 Nonetheless, different authors have criticized patient-centered care for the focus on transferring responsibility for the health outcomes to the patient instead of proving them with the necessary support for a good decision-making process.101 Yet, organizations continue to promote patient-centered care highlighting the patient satisfaction while not addressing the other aspects to achieving holistic/comprehensive care.30,102,103

Patient-centered care is linked to 3 concepts: (1) expanded view of illness, (2) patient participation in care, and (3) provider-patient relationship.102 International evidence indicates the focus on the last 2 concepts,30,101,104 while largely ignoring the expanded view of health, not only within the context of illness, which is important for Chile due to the national health policy.13

An important reason noted in the literature for the focus on patient-centered care is to shift the care responsibility from the health facilities and physicians to the patients and families. As patients become increasing responsible for their own health, there is a risk reduction in legal for deficits in care actions against hospitals, health centers, and physicians.30 In this study, we use person-centered concept instead of patient-centered care discussed in Starfield’s work.39,105 Eklund et al106 discussed the similarities and differences between these 2 concepts, observing that the person- and patient-centered care have at least 9 features in common: empathy, respect, engagement, relationship, communication, shared decision making, holistic focus, individualized focus, and coordinated care. However, the 2 concepts also differ in important ways. In the first case, the main goal is a meaningful life for the person, and in the second case, the goal is a functional life for the patient. For this reason, the authors believe the patient-centered approach to care replicates the biomedical model.

Despite the efforts made to advance public policy in economically developed countries, the interventions have not been translated into clear changes in the way health professionals perform their work.30 Although there is consensus about the value of interprofessional collaboration in providing high-quality health services, institutional structures often hinder the implementation of health interventions by collaborative teams.101 The power structures, such as legal, political, and economic, can delay and even obstruct the advancement of care models for interprofessional collaboration.30,101 Several authors30,102,103 suggested the process is handicapped by maintaining the traditional medical power structures that include defining work only to be completed by physicians, limiting the autonomy of other competent and capable professionals; preserving the fee-for-service payment model that reinforces medical power through only reimbursing physicians for services; and measuring health impact and team performance indicators based on the biomedical model.

The power structure influence can be minimized by applying process indicators that focus on measuring work characteristics specific to teams.103 For example, the number of team meetings is relatively simple to measure; however, there should be a group of indicators specific to the care model. This is important as researchers have noted that only implementing team meetings may not achieve the full extent of the expected professional interactions. In this regard, van Dongen et al104 reported team meetings alone were not successful in developing shared care plans that included the perspectives of different disciplines as well as the patient. Importantly, the researchers noted this reality was unrecognized by the professionals, who individually perceived the meetings to be patient-centered (defined in the study as the care that requires coordinated inputs from a wide range of health care professionals to enhance quality of care). However, in a related study,107 the amount of interprofessional collaboration to develop care plans was reported to be correlated to a combination of 5 factors, including patient, professional, interpersonal, organizational, and external. As such, the program documents need to include strong, coherent, and concrete language to guide the way professionals work in the PHC centers, as well as to establish the process and result indicators that reflect the chosen care model. This is perhaps one explanation for international health policy initiatives failing to accomplish their primary purpose.

In terms of this study, the interventions that should be independently performed need to be clearly delineated, and by which discipline. Similarly, the way the activity is completed, and the result is communicated to the entire team must be clearly defined. Then, the interventions requiring collaboration between disciplines need to be developed within each program, such as the case for people living with diabetes managed by the physicians, nurses, dieticians, and physical therapists. By focusing on compatibilization, or defining how the 2 models can coexist to increase the quality of care, as the balance between autonomy and interdependence will favor collaborative work.108

Despite the introduction of innovations to establish new institutional realities,109 the results demonstrate a tendency to maintain the traditional processes in written documents perceived to be effective. Considering the type of professional interactions necessary to achieve the goal of person-centered care and the incremental nature of policy making, existing policies need to be revised to overcome the unintended traditional barriers to collaborative work. This can be completed by launching new guidelines that enhance communication processes, encourage professional interactions, and clearly define shared responsibility for the disciplines expected to provide person-centered care.24,42,110 However, we need to be mindful that on occasion collaboration is not necessary, as some interventions can be implemented better and/or safer as a uniprofessional task.111

Finally, the presence of intersectoral work, as a type of interaction explicitly stated in the program documents, was unexpected. Following the Alma Ata declaration “health for all”112 and the current World Health Organization advocacy for “health in all policies,”113 the health sector needs to work intersectoral, with other economic sectors within and across national boundaries, to widely promote and provide health in an explicit manner.114 The inclusion of intersectoral work as an explicit concept in the program documents appears to be linked to the concepts in this study; however, additional research is necessary to consider the link between the policy and the program, that include the person and practice environment. Yet, we must be mindful that Chile does not have a periodical process to review, identify, and prioritize national health research needs.115

Limitations and Strengths

With a document analysis, three principle limitations need to be recognized.116 First, there is the potential for insufficiency of context as the program documents were not written for research. For example, there were differences in the format of the program documents, which increases the potential for error in extracting the data consistently across documents. Despite this limitation, the inclusion of all the documents prevented the introduction of bias into the document analysis. Second, there could be important program documents, or other related information, missing from the sample due to low retrievability associated with filing methods and storage locations. And, biased selectivity47 is possible with errors in search strategy and document selection, and missing documents. However, the database was searched multiple times by the investigators, a comprehensive group of terms was used for the search, and the primary investigators are familiar with the government program documents. In addition, the database was searched independently at the conclusion of the study to seek missing documents; none were identified. Finally, the context of the health policy, the program documents, and the primary care center culture might not be guided by the documents, and there might be differences between what is written and what is done. Although this is recognized, additional research is necessary to understand this possibility in practice. Despite the stated limitations, the data analysis was credible, dependable, confirmable, and transferable with trustworthiness always the focus.56

In terms of strengths, this study is the first step in the path to understanding the impact of health policies on the work resulting from the health programs in Chile. This is a relevant contribution to the literature as few studies address collaborative work in the context of health policy.32 Furthermore, this study address the publication bias that produces a knowledge deficit from alternative cultures and countries with different languages, cultures, and general realities, such as Chile in South America.102 In addition, this study serves as an example for researchers interested in analyzing policies, efficiently and cost-effectively,47 to understand their potential impact on primary and community health programs. The analysis of public policy documents provides an important context for comparing the intended work design with the resulting structures that define the actual work. Unambiguous policies that favor collaborative work make it possible to work this way to achieve an integral approach to caring for individuals, families, and communities. Finally, the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were applied to disseminate the results of this (see Supplementary Table 3).

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the relationships between the written structures, elaborated processes, and anticipated outcomes in primary health care. In general, the program justifications principally referenced the biopsychosocial model with multiple biomedical interventions and independent type professional work. Few programs were consistent in defining their justifications, interventions, and interactions in accordance with the national health policy focused on Integral Family and Community Health Model. In closing, health policies in Chile, and possibly other countries, need to be clearly translated into program documents that adhere to the expectations for providing person-centered care within the context of the primary care environment by organizing care processes that encourage interprofessional interactions and collaborative work. As national health policies directly impact the way primary care centers provide primary care services day-to-day to individuals, families, and communities, additional research is necessary to understand the relationship between the findings of this study with the reality of work in the primary care centers. In closing, this study represents the first step in a research journey to evaluate and define these relationships in more depth.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-1_2020.02.12_-_Data-quotes for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-2_2020.04.10_-_Program_summaries for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-3_2020.04.13_-_SRQR for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Footnotes

Author Note: Patrick A. Palmieri is also affiliated with Center for Global Nursing, Texas Woman’s University (Houston, TX, USA).

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was partially funded by the Agencia Nacional de Investigacion y Desarrollo de Chile through the Programa de Formación de Capital Humano Avanzado, National Doctoral Student Scholarship (2017-21171818) received by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino; and partially funded by the Universidad Norbert Wiener through a research dissemination award (VRI-D-04-001-RDG) from the Universidad Norbert Wiener recieved by Dr. Patrick A. Palmieri.

ORCID iDs: Patrick A. Palmieri  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0765-0239

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0765-0239

Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8153-508X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8153-508X

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. A vision for primary health care in the 21st century: towards universal health coverage and the sustainable development goals. 2018. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/vision.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. White F. Primary health care and public health: foundations of universal health systems. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:103-116. doi: 10.1159/000370197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. 2016. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://hsc.unm.edu/ipe/resources/ipec-2016-core-competencies.pdf

- 4. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457-502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Starfield B. Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity, and efficiency of health services. SESPAS report 2012. Gac Sanit. 2012;26(suppl 1):20-26. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reeve J. Primary care redesign for person-centred care: delivering an international generalist revolution. Aust J Prim Health. 2018;24:330-336. doi: 10.1071/PY18019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kusnanto H, Agustian D, Hilmanto D. Biopsychosocial model of illnesses in primary care: a hermeneutic literature review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:497-500. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_145_17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedical science. Science. 1997;196:129-136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wade DT, Halligan PW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:995-1004. doi: 10.1177/0269215517709890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Borrell-Carrió F, Suchman AL, Epstein RM. The biopsychosocial model 25 years later: principles, practice, and scientific inquiry. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:576-582. doi: 10.1370/afm.245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. De Consultorio a Centro de Salud: Marco Conceptual. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales. OrientacionesPara La Implementación Del Modelo de Atención Integral de SaludFamiliar y Comunitaria. Subsecretaría de Redes Asistenciales; 2012. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/e7b24eef3e5cb5d1e0400101650128e9.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gobienero de Chile. Estrategia Nacional de Salud Para El Cumplimiento de Los ObjetivosSanitarios de La Década 2011-2020. Ministerio de Salud; 2011. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/c4034eddbc96ca6de0400101640159b8.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hewa S, Hetherington RW. Specialists without spirit: limitations of the mechanistic biomedical model. Theor Med. 1995;16:129-139. doi: 10.1007/BF00998540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Morgan S, Pullon S, McKinlay E. Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52:1217-1230. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Woods D. Interprofessional teamwork for multi-professional practice: does it work in primary care? Pract Nurs. 2018;29:88-93. doi: 10.12968/pnur.2018.29.2.88 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brown JB, Ryan BL, Thorpe C, Markle EK, Hutchison B, Glazier RH. Measuring teamwork in primary care: triangulation of qualitative and quantitative data. Fam Syst Health. 2015;33:193-202. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements for interprofessional education. Part 1: the learner, the educator and the learning context. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(suppl 1):21-38. doi: 10.1080/13561820500083550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi BCK, Pak AWP. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clin Investig Med. 2006;29:351-364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Matuda CG, da Silva Pinto NR, Martins CL, Frazão P. Colaboração interprofissional na Estratégia Saúde da Família: implicações para a produção do cuidado e a gestão do trabalho [in Portugese]. Cien Saude Colet. 2015;20:2511-2521. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232015208.11652014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. D’Amour D, Goulet L, Labadie JF, Martín-Rodriguez LS, Pineault R. A model and typology of collaboration between professionals in healthcare organizations. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:188. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Starfield B. Global health, equity, and primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20:511-513. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.06.070176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mulvale G, Embrett M, Razavi SD. “Gearing Up” to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:83. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0492-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liberati EG, Gorli M, Scaratti G. Invisible walls within multidisciplinary teams: disciplinary boundaries and their effects on integrated care. Soc Sci Med. 2016;150:31-39. doi: 10.1016/J.SOCSCIMED.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:166-171. doi: 10.1370/afm.1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Working Party Group on Integrated Behavioral Healthcare; Baird M, Blount A, et al. Joint principles: integrating behavioral health care into the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:183-185. doi: 10.1370/afm.1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. D’Amour D, San Martin Ferrada-Videla M, Rodriguez L, Beaulieu MD. The conceptual basis for interprofessional collaboration: core concepts and theoretical frameworks. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(suppl 1):116-131. doi: 10.1080/13561820500082529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32:1-3. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bitton A, Fifield J, Ratcliffe H, et al. Primary healthcare system performance in low-income and middle-income countries: a scoping review of the evidence from 2010 to 2017. BMJ Glob Heal. 2019;4(suppl 8):e001551. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell GM, Miller WL, Gunn JM, et al. Contextual levers for team-based primary care: lessons from reform interventions in five jurisdictions in three countries. Fam Pract. 2018;35:276-284. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kabene SM, Orchard C, Howard JM, Soriano MA, Leduc R. The importance of human resources management in health care: a global context. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wranik WD, Price S, Haydt SM, et al. Implications of interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health outcomes: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy. 2019;123:550-563. doi: 10.1016/J.HEALTHPOL.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Téllez A. Atención primaria: factor clave en la reforma al sistema de salud [in Spanish]. 2006. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://politicaspublicas.uc.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/atencion-primaria-factor-clave-en-la-reforma-al-sistema-de-salud.pdf

- 34. Becerril-Montekio V, de Dios Reyes J, Manuel A. Sistema de salud de Chile. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53:s132-s142. doi: 10.1590/S0036-36342011000800009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ministerio de Salud. Ministerio de Salud—Gobierno de Chile. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/

- 36. DataChile. Chile. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://es.datachile.io/geo/chile

- 37. Sistema Nacional de Información Municipal. Datos municipales. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.subdere.gov.cl/sala-de-prensa/sistema-nacional-de-informacion-municipal-sinim-programa-pionero-de-la-subdere-cumple.

- 38. Benavides Salazar P, Castro R, Jones I. Sistema Público de Salud: Situación Actual y Proyecciones Fiscales 2013-2050. Dirección de Presupuestos del Ministerio de Hacienda; 2013. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.dipres.gob.cl/598/articles-117505_doc_pdf.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bitton A, Ratcliffe HL, Veillard JH, et al. Primary health care as a foundation for strengthening health systems in low- and middle-income countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:566-571. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3898-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. División de Atención Primaria. Centro de Salud Familiar. 2008. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/mision-y-funciones-2/

- 41. Subsecretaria de Redes Asistenciales. Modelo de Atención Integral Con Enfoque Familiar y Comunitario En Estableci-mientos de La Red de Atención de Salud. Gobierno de Chile; 2009. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/18.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 42. World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. World Health Organization; 2010. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gutiérrez Ossa JA, Restrepo Avendaño RD, Zapata Hoyos JS. Formulación, implementación y evaluación de políticas públicas desde los enfoques, fines y funciones del Estado. CES Derecho. 2017;8:333-351. doi: 10.21615/cesder.8.2.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mintzberg H. Structure in 5’s: a synthesis of the research on organization design. Manage Sci. 1980;26:322-341. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.26.3.322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McPhail CJ. From tall to matrix: redefining organizational structures. Change. 2016;48:55-62. doi: 10.1080/00091383.2016.1198189 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kuckartz U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software. Sage [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J. 2009;9:27-40. doi: 10.3316/QRJ0902027 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reynolds J, Kizito J, Ezumah N, Mangesho P, Allen E, Chandler C. Quality assurance of qualitative research: a review of the discourse. Health Res Policy Syst. 2011;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic analysis: striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16. doi: 10.1177/1609406917733847 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mays N, Pope C. Rigour and qualitative research. Br Med J. 1995;311:109-112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6997.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Krefting L. Rigor in qualitative research: the assessment of trustworthiness. Am J Occup Ther. 1991;45:214-222. doi: 10.5014/ajot.45.3.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Introduction: the discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, eds. Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Sage; 2000:1-28. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Titscher S, Meyer M, Wodak R, Vetter E. Ethnographic methods. In: Methods of Text and Discourse Analysis: In Search of Meaning. 1st ed. Sage; 2000:90-103. doi: 10.4135/9780857024480.n7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kracauer S. The challenge of qualitative content analysis. Public Opin Q. 1952;16:631-642. doi: 10.1086/266427 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th ed. SAGE; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. 2nd ed. Wiley; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Peers C. Policy analysis and document research. In: Fleer M, van Oers B, eds. International Handbook of Early Childhood Education. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Springer; 2018:203-224. doi: 10.1007/978-94-024-0927-7_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Browne J, Coffey B, Cook K, Meiklejohn S, Palermo C. A guide to policy analysis as a research method. Health Promot Int. 2019;34:1032-1044. doi: 10.1093/heapro/day052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Buckland M. What is a ‘“document”‘? J Am Soc Inf Sci. 1997;48:804-809. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Altheide D, Coyle M, DeVriese K, Schneider C. Emergent qualitative document analysis. In: Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P, eds. Handbook of Emergent Methods. Guilford Press; 2008:127-151. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Qual Soc Res. 2000;1:20. doi: 10.17169/fqs-1.2.1089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Bryman A. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Rapley T. Doing Conversation, Discourse and Document Analysis. 2nd ed. Sage; 2007. doi: 10.4135/9781849208901 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Altheide DL, Schneider CJ. Process of qualitative document analysis. In: Qualitative Media Analysis. 2nd ed. Sage; 2013:389-74. doi: 10.4135/9781452270043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Coffey A, Atkinson P. Encontrar El Sentido a Los Datos Cualitativos: Estrategias Complementarias de Investigación [Making Sense of Qualitative Data: Complementary Research Strategies]. Universitat d’Alacant; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bauer MW, Gaskell G, Allum N. Quality, quantity and knowledge interests: avoiding confusions. In: Bauer M, Gaskell G, eds. Qualitative Researching With Text, Image and Sound. Sage; 2000:4-17. doi: 10.4135/9781849209731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Crowe M, Inder M, Porter R. Conducting qualitative research in mental health: thematic and content analyses. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:616-623. doi: 10.1177/0004867415582053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:398-405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bramer WM, de Jonge GB, Rethlefsen ML, Mast F, Kleijnen J. A systematic approach to searching: an efficient and complete method to develop literature searches. J Med Libr Assoc. 2018;106:531-541. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Adams J, Hillier-Brown FC, Moore HJ, et al. Searching and synthesising “grey literature” and “grey information” in public health: critical reflections on three case studies. Syst Rev. 2016;5:164. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0337-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Departamento de Estadísticas e Información en Salud. Resúmenes estadísticos mensuales DEIS. 2016. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.deis.cl/resumenes-estadisticos-mensuales-deis/

- 72. Julien H. Content analysis. In: Given LM, ed. SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Sage; 2008:120-121. doi: 10.4135/9781412963909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Joffe H, Yardley L. Content and thematic analysis. In: Yardley L, Marks DF, eds. Research Methods for Clinical and Health Psychology. 1st ed. Sage; 2004:56-68. doi: 10.4135/9781849209793 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int J Qual Methods. 2006;5:80-92. doi: 10.1177/160940690600500107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie JA. Qualitative data analysis: a compendium of techniques and a framework for selection for school psychology research and beyond. Sch Psychol Q. 2008;23:587-604. doi: 10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107-115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H. Qualitative content analysis: a focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):1-10. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pinto AD, Manson H, Pauly B, Thanos J, Parks A, Cox A. Equity in public health standards: a qualitative document analysis of policies from two Canadian provinces. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:1-10. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-11-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lincoln SY, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. SAGE; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Connelly LM. Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nurs. 2016;25:435-436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Groenewald T. Memos and memoing. In: Given LM, ed. The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Sage; 2008:505-506. doi: 10.4135/9781412963909.n260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Birks M, Chapman Y, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs. 2008;13:68-75. doi: 10.1177/1744987107081254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Cutcliffe JR, McKenna HP. Establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings: the plot thickens. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30:374-380. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. King N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In: Cassell C, Symon G, eds. Essential Guide to Qualitative Methods in Organizational Research. Sage; 2004:257-270. [Google Scholar]

- 85. O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245-1251. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Greenhalgh T. How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence Based Medicine. 5th ed. Wiley; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Programa Nacional de Salud de La Infancia Con Enfoque Integral. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://diprece.minsal.cl/wrdprss_minsal/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/2013_Programa-Nacional-de-Salud-de-la-infancia-con-enfoque-integral.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Programa Nacional de Salud Integral de Adolescentes y Jóvenes: Plan de Acción 2012-2020. 2012. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/portal/url/item/d263acb5826c2826e04001016401271e.pdf

- 89. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Programa Nacional de Salud de Las Personas Adultas Mayores. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2014. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://bibliotecaminsal-chile.bvsalud.org/lildbi/docsonline/get.php?id=4862 [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Manual Orientación Técnica: Programa de Atención Domiciliaria a Personas Con Dependencia Severa. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2018. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.araucaniasur.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/OOTT-dependencia-severa-final-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 91. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Programa de Rehabilitación Integral En La Red de Salud. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2014Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.araucanianorte.cl/images/PDF-WORD/Res-Ex-1167-Programa-Rehabilitacion-Integral-2015-APS-21112014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Manual Operativa Programas de Salud Respiratoria. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/files/Manual_operativo_Programas_de_Salud_Respiratoria.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 93. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones y Lineamientos Programa Vida Sana: Intervención En Factores de Riesgo de Enfermedades No Transmisibles. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/015.OT-Vida-Sana.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientación Técnica Programa Más Adultos Mayores Autovalentes. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://www.bibliotecaminsal.cl/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/013.Orientación-Técnica-Programa-Ms-Autovalentes.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 95. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientación Técnica: Programa de Salud Cardiovascular. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2017. http://bibliotecaminsal-chile.bvsalud.org/lildbi/docsonline/get.php?id=4784 [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Manual de Programas Alimentarios. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2011. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://bibliotecaminsal-chile.bvsalud.org/lildbi/docsonline/get.php?id=5237 [Google Scholar]

- 97. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Salud Mental En La Atención Primaria de Salud. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2015. Accessed April 27, 2020 http://bibliotecaminsal-chile.bvsalud.org/lildbi/docsonline/get.php?id=4651 [Google Scholar]

- 98. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Politica Nacional de Salud Sexual y Salud Reproductiva. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2018. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://diprece.minsal.cl/wrdprss_minsal/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/POLITICA-NACIONAL-DE-SALUD-SEXUAL-Y-REPRODUCTIVA-..pdf [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Orientaciones Técnico Administrativas Para La Ejecución Del Programa Odontológico Integral. Ministerio de Salud de Chile; 2019. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://diprece.minsal.cl/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Orientación-Técnica-Programa-Odontológico-Integral-2019.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 100. Oliver TR. The politics of public health policy. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:195-233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Fox A, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaborative patient-centred care: a critical exploration of two related discourses. J Interprof Care. 2014;29:113-118. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.954284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Agreli HF, Peduzzi M, Silva MC. Atenção centrada no paciente na prática interprofissional colaborativa [Patient centred care in interprofessional collaborative practice]. Interface - Comun Saúde, Educ. 2016;20:905-916. doi: 10.1590/1807-57622015.0511 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Donnelly C, Ashcroft R, Mofina A, Bobbette N, Mulder C. Measuring the performance of interprofessional primary health care teams: understanding the teams perspective. Prim Heal Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e125. doi: 10.1017/S1463423619000409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. van Dongen JJ, van Bokhoven MA, Daniëls R, Lenzen SA, van der Weijden T, Beurskens A. Interprofessional primary care team meetings: a qualitative approach comparing observations with personal opinions. Fam Pract. 2017;34:98-106. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Starfield B. Is patient-centered care the same as person-focused care? Perm J. 2011;15:63-69. doi: 10.7812/tpp/10-148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. HåkanssonEklund J, Holmström IK, Kumlin T, et al. “Same same or different?” A review of reviews of person-centered and patient-centered care. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102:3-11. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.08.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. van Dongen JJJ, Lenzen SA, van Bokhoven MA, Daniëls R, van der Weijden T, Beurskens A. Interprofessional collaboration regarding patients’ care plans in primary care: a focus group study into influential factors. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17:58. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0456-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. MacNaughton K, Chreim S, Bourgeault IL. Role construction and boundaries in interprofessional primary health care teams: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:486. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Dente B, Subirats J. Decisiones Públicas: Análisis y Estudio de Los Procesos de Decisión En Políticas Públicas. Grupo Planeta; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 110. Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G. Effective interprofessional teams: “contact is not enough”; to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28:228-234. doi: 10.1002/chp.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Petit dit Dariel O, Cristofalo P. A meta-ethnographic review of interprofessional teamwork in hospitals: what it is and why it doesn’t happen more often. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2018;23:272-279. doi: 10.1177/1355819618788384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pan American Health Organization. Declaración de Alma-Ata. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2012/Alma-Ata-1978Declaracion.pdf

- 113. Global Conference on Health Promotion. Health in All Policies (HiAP): framework for country action. Health Promot Int. 2016;29(suppl 1):S19-S28. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dau035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Gobienero de Chile. ¿Salud Para Todos? La Atención Primaria de Salud En Chile y Los 40 Años de Alma Ata. Ministerio de Salud; 2018. Accessed April 27, 2020 https://www.academia.edu/36121593/_Salud_para_todos_La_Atenci%C3%B3n_Primaria_de_Salud_en_Chile_y_los_40_a%C3%B1os_de_Alma_Ata_1978-2018 [Google Scholar]

- 115. Zitko P, Borghero F, Zavala C, et al. Priority setting for mental health research in Chile. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2017;11:61. doi: 10.1186/s13033-017-0168-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 2nd ed. Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-1_2020.02.12_-_Data-quotes for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-2_2020.04.10_-_Program_summaries for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Supplemental material, JPC-20-0050R1_Document-analysis-health-programs-Chile_Table-suppl-3_2020.04.13_-_SRQR for National Health Policy Reform for Primary Care in Chile: A Qualitative Analysis of the Health Program Documents by Karen A. Dominguez-Cancino, Patrick A. Palmieri and Maria Soledad Martinez-Gutierrez in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health