Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province and has rapidly spread all over the world. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 01/30/2020 and recognized it as a pandemic on 03/11/2020. The number of people diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide crossed the one million mark on 04/02/2020; two million mark on 04/15/2020; three million mark on 04/27/2020 and the four million mark on 05/09/2020. Despite containment efforts, more than 187 countries have been affected with more than 4,178,346 cases in the world with maximum being in USA (1,347,936) followed by 227,436 in Spain and 224,422 in United Kingdom as of May, 2020. COVID-19 is the latest threat to face mankind cutting across geographical barriers in a rapidly changing landscape. This review provides an update on a rapidly evolving global pandemic. As we face the threat of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases, this is a stark reminder to invest in population health, climate change countermeasures, a global health surveillance system and effective research into identifying pathogens, their treatment and prevention and effective health delivery systems.

Keywords: Novel coronavirus, COVID-19, SARS CoV-2, Global health emergency, Pandemic

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The disease was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, the capital of China's Hubei province, and has since spread globally, resulting in the ongoing 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic. There was an epidemiological association with a seafood market in Wuhan where there was also a sale of wild animals, which was closed on 01/01/2020. 1 Case was first reported to WHO on 12/31/2019 of unknown pneumonia with the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission saying they were monitoring the situation closely. Subsequent information was provided on 11th and 12th of January. The genetic sequence of the 2019-nCoV was reported to the WHO on 01/12/2020 and noted to be a β CoV of group 2B with at least 70% similarity in genetic sequence to SARS-CoV and has been named 2019-nCoV by the WHO [1].

Subsequently, five additional 2019-nCoV sequences were deposited on the GSAID database on 11th January from institutes across China (Chinese CDC, Wuhan Institute of Virology and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College) and allowed researchers around the world to begin analyzing the new CoV. By 17th January, there were 62 confirmed cases in China and importantly, three exported cases of infected travelers who were diagnosed in Thailand (2) and Japan (1). Within 1 month, this virus spread quickly throughout China during the Chinese New Year – a period when there is a high level of human mobility among Chinese people [2].

The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 01/30/2020 and recognized it as a pandemic on 03/11/2020 [3].

The number of people diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide crossed the one million mark on 04/02/2020; the case fatality rate (CFT) across 204 countries and territories was 5·2%. By comparison, the SARS epidemic infected 8096 people in 29 countries from November, 2002, to July, 2003, and had a case fatality rate of 9·6%, whereas the MERS outbreak infected 2494 people in 27 countries from April, 2012, to November, 2019, and had a case fatality rate of 34·4% [4,5].

Epidemiology

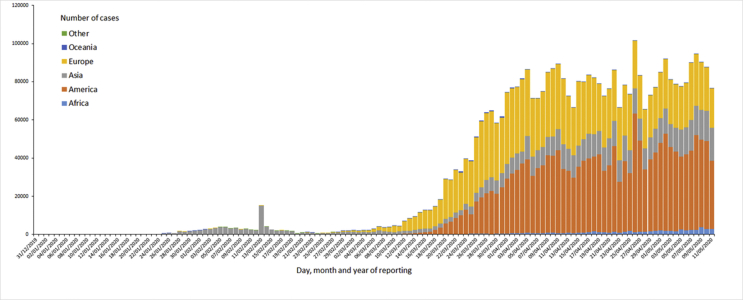

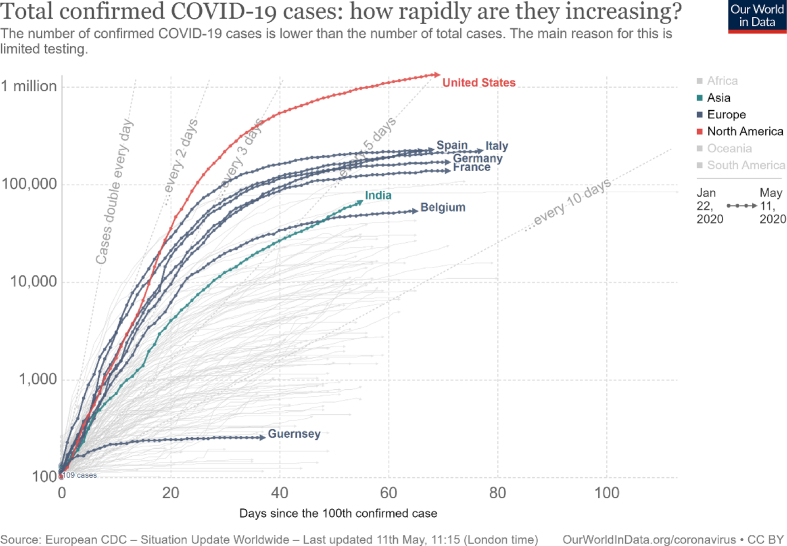

As of 05/12/2020, as shown in Fig. 1, this has evolved into a pandemic affecting 187 countries/regions with 1,484,811 cases in the world with maximum being in USA(1,347,936) followed by 227,436 in Spain and 224,422 in United Kingdom at the time of writing [6]. It is an un-precedented global health crisis with 286,355 deaths since the virus was first reported. U.S.A has been particularly hard hit with 80,684 deaths reported followed by United Kingdom with 32,141 deaths and Italy with 30,739 deaths. In USA, New York City has emerged a center of this global crisis with 14,928 deaths reported in New York City alone. There are 183,662 cases in New York followed by 140,000 in New Jersey. The first case of COVID-19 in US was reported on 01/22/2020 [6]. [Fig. 2].

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of 14-day cumulative number of reported COVID-19 cases per 100,000 population, worldwide.

Fig. 2.

Total confirmed COVID-19 cases: how rapidly are they increasing? from 01/22/2020–05/11/2020.

The number of people diagnosed with COVID-19 worldwide crossed the one million mark on 04/02/2020: two million mark on 04/15/2020; three million mark on 04/27/2020 and the four million mark on 05/09/2020. It took 83 days to reach the first million cases worldwide and just 14 days for the second and third million subsequently [6].

These numbers change rapidly as this is an evolving pandemic.

Mortality from one country to the other has differed depending on multiple parameters like the number of people tested, healthcare delivery, population demographics and factual reporting. Italy has a CFR of 13.98% (number of deaths per 100 confirmed cases) and 505.44 deaths per 100,000 population. Corresponding numbers in United Kingdom are 14.53% and 469.24 deaths per million. In USA these numbers stand at 5.98% and 240.26 deaths per million respectively as of 05/11/2020 [6].

As of 2 April, nearly 300 million people, or about 90% of the population, are under some form of lockdown in the United States. On 26 March, 1.7 billion people worldwide were under some form of lockdown which increased to 2.6 billion people two days later—around a third of the world's population [7].

As of 04/03/2020, over 421 million learners were out of school due to school closures in response to COVID-19. According to UNESCO monitoring, over 200 countries have implemented nationwide closures, impacting about 98% of the world's student population [8].

Earlier CDC reports have indicated that 31% of cases, 45% of hospitalizations, 53% of ICU admissions, and 80% of deaths occurred among adults aged ≥65 years with the highest percentage of severe outcomes among persons aged ≥85 years. Severe illness leading to hospitalization, including ICU admission and death, can occur in adults of any age with COVID-19. However, individuals aged <19 appear to have milder COVID-19 illness [9].

History of illness associated with coronavirus

Coronavirus has an extensive history going back to the 1930's. Avian coronavirus, initially called infectious bronchitis virus of chickens, mainly infecting domesticated chickens was first isolated in the 1930's followed by two more animal coronaviruses, mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV) in the 1940's [10].

Human coronavirus (HCoV) was historically known to cause a large proportion of minor upper respiratory tract infections. Tyrrell and Bynoe [11], first found in 1965, that a virus named B 814 caused common cold in adults. Hamre and Procknow [12], first grew a virus they called 229 E, in tissue cultures from samples obtained from medical students with colds. Almeida and Tyrrell performed electron microscopy on fluids from organ cultures infected with B814 and found particles that resembled the infectious bronchitis virus of chickens. Tyyrell et al., in the late 1960's, demonstrated above zoonotic viruses and human strains, to be morphologically same and a new genus of viruses of coronavirus was coined [13].

In late 2002, SARS (Severe acute respiratory syndrome) epidemic appears to have started in Guangdong Province, China. In 2017, Chinese scientists led by Shi Zheng-Li and Cui Jie of the Wuhan Institute of Virology, China traced the source of the outbreak to horseshoe bats with civets acting as an intermediary. SARS was a relatively rare disease; at the end of the epidemic in June 2003, the incidence was 8,422 cases with a CFR ranging from 0% to 50% depending on the age group of the patient. Overall case fatality rate was 9.6%. In the United States, only 8 people had laboratory evidence of SARS-CoV infection during the 2003 outbreak. The World Health Organization declared severe acute respiratory syndrome contained on 07/05/2003 [14].

In September 2012 another novel coronavirus emerged in Saudi Arabia, first identified as Novel Coronavirus 2012 and subsequently Human Coronavirus—Erasmus Medical Centre (HCoV-EMC) after the Dutch Erasmus Medical Centre which had sequenced the virus. In May 2013, the Coronavirus Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses adopted the official designation, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), which was further adopted by WHO [15]. MERS-CoV, also called Camel flu, is believed to be derived from bats with camels being involved in spread to Humans. At the end of 2017, just under 2000 cases were reported with a case fatality rate of 36%. Most cases have occurred in the Arabian Peninsula with a subsequent outbreak in 2015 in South Korea with 184 confirmed cases of infection and 19 deaths. Only two people in the U.S. have ever tested positive for MERS-CoV infection, both in 2014. Potential for periodic outbreaks remains, particularly in the Arabian Peninsula. Testing includes reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing of respiratory and serum specimens [16].

Virology and pathogenesis

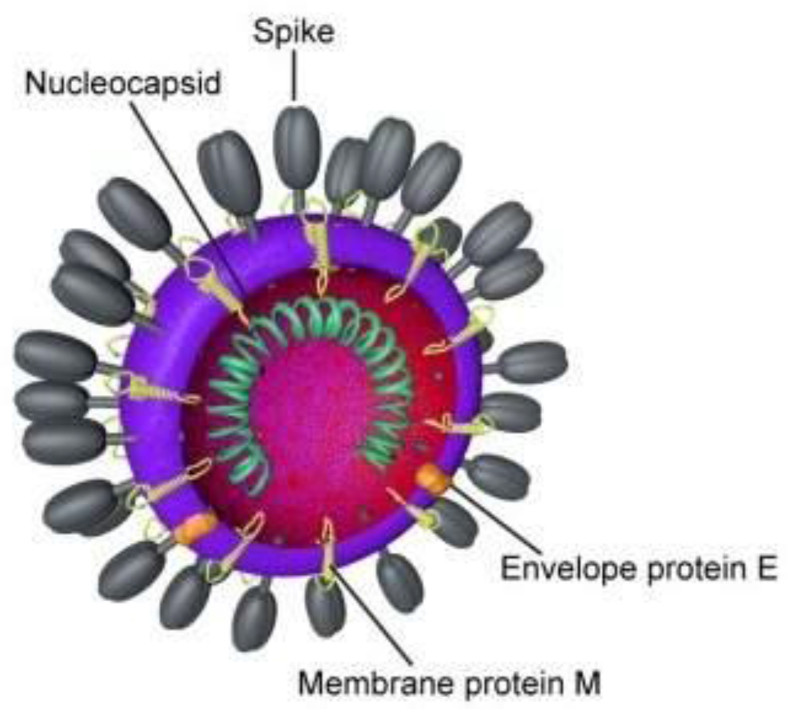

Coronaviruses (CoVs), are enveloped, non-segmented, positive-sense RNA viruses. They are characterized by club-like spikes that project from their surface and the largest identified RNA genomes, containing approximately 30 kilobase (kb) genome and a unique replication strategy. The strategy of replication of coronaviruses involves a nested set of messenger RNAs with common polyadenylated 3′ends. Only the unique portion of the 5′end is translated. Mutations are common in nature. In addition, coronaviruses are capable of genetic recombination if 2 viruses infect the same cell at the same time [17].

The name coronavirus is derived from Latin, corona, meaning crown or wreath. Due to characteristic appearance of virions by electron microscopy on the surface of the virus [Fig. 3], creating an image reminiscent of a crown or of a solar corona, coronavirus has acquired its name.

Fig. 3.

Diagram by Belouzard et al. (CC BY 3.0).

Tang et al. investigated the patterns of molecular divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and other related coronaviruses by studying the population genetic analyses of 103 genomes of SARS-CoV-2. They showed that SARS-CoV-2 viruses evolved into two major types (L and S types) with the S type being the more ancient version of SARS-CoV-2. L type was shown to be more aggressive than the S type and more prevalent in the early stages of the outbreak in Wuhan, the frequency of the L type decreased after early January 2020 possibly due to human intervention [18].

SARS-CoV-2 is genetically similar to other coronaviruses in the subgenus Sarbecovirus, a clade of betacoronaviruses formed by the coronavirus that causes SARS (SARS-CoV) and other SARS-CoV-like coronaviruses found in bats. Recombination between coronaviruses are common, and SARS-CoV is believed to be a recombinant between bat sarbecorviruses. Interestingly, the whole genome of SARS-CoV-2 is highly similar to that of a bat coronavirus detected in 2013 (>96% sequence identity), which suggests that the immediate ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 has been circulating in bats for at least several years [19].

ACE2 has been identified as a functional receptor for coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 infection is triggered by binding of the spike protein of the virus to ACE2, which is highly expressed in the heart and lungs. Binding of the S1 unit of the viral S protein to the host ACE2 cellular receptor facilitates viral attachment to the surface of target host cells. Viral S protein priming then requires S protein cleavage of S1 from S2 (and at another S2’ site) by the host cell serine protease TMPRSS2. The viral S2 subunit then drives fusion of the viral and host cell membranes [20].

Additionally, cytokine storm triggered by an imbalanced response by type 1 and type 2 T helper cells and respiratory dysfunction and hypoxemia caused by COVID-19 can result in damage to myocardial cells [21].

Pangolins, protected animals that are traded illegally in Asia and elsewhere, have been proposed as a potential amplifying host by some studies [22].

Transmission and infection

The reproductive number is the number of cases, on average, an infected person will cause during their infectious period. The actual R0 for SARS-CoV-2 remains to be determined with other estimates generally ranging between 1.5 and 3.5. In contrast, R0 for measles is 12–18 making it highly infectious and for Influenza it is 2–3. For the SARS pandemic in 2003, scientists estimated the original to be around 2.75 [23].

However, a super-spreader is an individual who is more likely to infect others, compared with a typical infected person. Super-spreaders continue to be of particular concern in epidemiology and they have been identified in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

WHO says it is primarily spread during close contact and by small droplets produced when people cough, sneeze or talk. Early on, many of the patients at the epicenter of the outbreak in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China had some link to a large seafood and live animal market, suggesting animal-to-person spread. Later, a growing number of patients reportedly did not have exposure to animal markets, indicating person-to-person spread. Currently the virus seems to be spreading via community spread with individuals getting infected without a definite exposure [24].

SARS-CoV-2 can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours, and on surfaces up to days; the median half-life of SARS-CoV-2 was approximately 1.1 h in aerosols, 5.6 h on stainless steel and 6.8 h on plastic; no viable virus was measured on cardboard after 24 h, but virus was still detectable (depending on the inoculum shed) on plastic and stainless steel after 72 h aerosol and fomite transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is plausible, since the virus can remain viable and infectious in aerosols for hours and on surfaces up to days (depending on the inoculum shed) [25].

Xiao et al. demonstrated SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and intracellular staining of viral nucleocapsid protein in gastric, duodenal, and rectal epithelia demonstrate that SARS-CoV-2 infects these gastrointestinal glandular epithelial cells. In their study they noted that more than 20% of patients with SARS-CoV-2, were observed to have viral RNA positive in feces, even after test results for viral RNA in the respiratory tract converted to negative, indicating that the viral gastrointestinal infection and potential fecal-oral transmission can last even after viral clearance in the respiratory tract. This has strong implications in preventing further transmission via the feco-oral route if rRT-PCR result of a fecal sample remains positive [26].

Possible intrauterine transfer has been reported, with reports of abnormal IgM and IgG and abnormal cytokine test results in an infant born via Caesarean section to a covid + mother. The elevated IgM antibody level suggests that the neonate was infected in utero. as IgM antibodies are not transferred to the fetus via the placenta [27].

The median incubation period of COVID-19 has been estimated to be 5.1 days, and estimated that nearly all infected persons who have symptoms will do so within 12 days of infection. Clinical descriptions of asymptomatic phases after possible exposure range from 2 to 14 days. A 14-day period for monitoring after potential exposure is generally recommended, and modeling predicts that 101 out of every 10,000 cases (99th percentile) will develop symptoms after 14 days of active monitoring or quarantine [28].

Clinical manifestations

Patients’ clinical manifestations include fever, nonproductive cough, dyspnea, myalgia, fatigue, normal or decreased leukocyte counts, and radiographic evidence of pneumonia. Organ dysfunction (e.g., shock, acute respiratory distress syndrome [ARDS], acute cardiac injury, and acute kidney injury) and death can occur in severe cases [29].

The median time from symptom onset to the development of pneumonia is approximately 5 days, and the median time from symptom onset to severe hypoxemia and ICU admission is approximately 7–12 days. Critically ill patients with COVID-19 are older and have more comorbidities, including hypertension and diabetes, than do non-critically ill patients.

Acute hypoxemic respiratory failure—sometimes with severe hypercapnia—from acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is the most common complication (in 60–70% of patients admitted to the ICU), followed by shock (30%), myocardial dysfunction (20–30%), and acute kidney injury (10–30%) [30].

Common CT findings are ground glass opacities and consolidation. CT chest can be normal in patients with non-severe or severe covid and should not be relied upon for ruling out COVID-19. Also, abnormal finding noted on CT might not be specific for COVID-19.

Hematological findings include lymphocytopenia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia. Most of the patients had elevated levels of C-reactive protein; less common were elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, creatine kinase, and d-dimer. Patients with severe disease had more prominent laboratory abnormalities (including lymphocytopenia and leukopenia) than those with non-severe disease [31].

Mortality has been found to be markedly higher in patients with elevated troponin T (TnT) levels than in patients with normal TnT levels (59.6% vs 8.9%). 27 Exuberant elevation of IP-10, MCP-3 and IL-1ra during SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with disease severity and fatal outcome [32].

Diagnosis

CDC recommends following revised guidelines for testing [33].

PRIORITIES FOR COVID-19 TESTING.

(Nucleic Acid or Antigen)

High priority.

-

•

Hospitalized patients with symptoms

-

•

Healthcare facility workers, workers in congregate living settings, and first responders with symptoms

-

•

Residents in long-term care facilities or other congregate living settings, including prisons and shelters, with symptoms

Priority.

-

•

Persons with symptoms of potential COVID-19 infection, including: fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, muscle pain, new loss of taste or smell, vomiting or diarrhea, and/or sore throat.

-

•

Persons without symptoms who are prioritized by health departments or clinicians, for any reason, including but not limited to: public health monitoring, sentinel surveillance, or screening of other asymptomatic individuals according to state and local plans.

To test for SARS-CoV-2, specimen testing (nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal aspirates or washes, nasopharyngeal or oropharyngeal swabs, bronchoalveolar lavage, tracheal aspirates, sputum, and serum) is performed using a real time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2. SARS-CoV-2 is not detected by standard respiratory viral panels, including those that test for the previously identified beta coronaviruses. Repeated sampling might be required when initial tests are negative despite suspicious clinical features [34].

Management

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and High flow nasal canula (HFNC) should be reserved for patients with mild ARDS with adequate precautions [35], use of personal protective equipment and use of negative pressure rooms due to concern of aerosolization from these procedures. A conservative or de-resuscitative fluid strategy with early detection of myocardial involvement through the measurement of troponin and beta-natriuretic peptide concentrations and echocardiography and early use of vasopressors and inotropes are recommended. Studies carried out in previous SARS epidemics have shown that corticosteroids had no impact on mortality but possible harms, including avascular necrosis, psychosis, diabetes, and delayed viral clearance [36]. At this time routine use of corticosteroids is not recommended.

Currently there are no proven therapies for treatment of COVID-19. There are ongoing trials on remdesivir, lopinavir–ritonavir, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), intravenous immunoglobulin, convalescent plasma, tocilizumab, favipiravir, and traditional Chinese medicines. No peer-reviewed, published safety data is available for SARS-CoV-2 on HCQ though it continues to be widely used [35].

Prone Ventilation is suggested for patients with refractory hypoxemia due to progressive COVID-19 pneumonia (i.e., ARDS). Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is suggested for patients with refractory hypoxemia due to progressive COVID-19 pneumonia (i.e., ARDS), if prone ventilation fails [35].

Kai Duan et al. showed that administration of convalescent plasma (CP) obtained from recovered COVID-19 patients who had established humoral immunity against the virus led to COVID-19 patients achieving serum SARS-CoV-2 RNA negativity after CP transfusion, accompanied by an increase of oxygen saturation and lymphocyte counts, and the improvement of liver function and CRP. Key factors in administering convalescent plasma include concerns that donor plasma must contain an adequate titre of neutralizing antibodies, be administered at the right treatment time point and risk of transmitting potential pathogens must be considered. Mass testing of recovered patients who meet above criteria can provide an efficacious treatment source for COVID- 19 patients [37].

Adequate measures to prevent transmission like hand washing, proper PPE, social distancing and use of negative pressure isolation rooms are the backbone in this pandemic and must stay in place.

Treatment and vaccine

There are currently no approved human coronavirus vaccines. Future considerations in development of a vaccine pose a conundrum. Previous novel vaccines towards disease such as dengue, SARS, respiratory syncytial virus have led to a counterproductive and potentially severe reaction known as immune enhancement [38].Neutralizing antibodies have been considered as an effective drug to treat or prevent virus infection, however a recent study has shown that about 30% of 300 patients failed to develop high titers of NAbs after COVID-19 infection, the disease duration of these patients was similar to other patients however it is unclear whether these patients are at a higher risk of rebound or reinfection. Elderly patients were noted to have a higher titre of NAbs with a stronger innate immunity response-clinical co-relation with disease recovery and severity needs to be further explored [32].

Response to the pandemic

Coronavirus makes clear what has been true all along. Your health is as safe as that of the worst-insured, worst-cared-for person in your society. It will be decided by the height of the floor, not the ceiling.

Anand Giridharadas @AnandWrites.

On 03/26/2020, dozens of UN human rights experts emphasized respecting the rights of every individual during the COVID-19 pandemic including rights to health care and government's responsibility to provide lifesaving interventions [39].

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development has launched a platform to provide timely and comprehensive information on policy responses in countries around the world, as well as viewpoints and advice [40].

Solidarity Trial is an initiative started in March 2020 by the World Health Organization to test drugs and drug combinations including Remdesivir, Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine combination, Ritonavir/lopinavir and Ritonavir/lopinavir & interferon-beta against SARS CoV-2.

According to the WHO Director General, the aim of the trial is to “dramatically cut down the time needed to generate robust evidence about what drugs work”. The first patient for this trial was one from Oslo University Hospital, Norway [41].

Going forward there must be greater investments in public health and emergency preparedness. USA spends approximately $275 per person per year (2.5 percent of all health care spending) inspite of spending about twice as much per capita on health care as the average among other OECD (Organization for Economic and Cooperation Development) nations. Universal health coverage, bi-directional sharing of data between low income and high-income countries, greater investment in healthcare by governments all around the world are measures that should be learnt and implemented after this pandemic [42].

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Hui D.S., I Azhar E., Madani T.A., Ntoumi F., Kock R., Dar O. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health — the latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;91:264–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GISAID database. 2020 coronavirus. J Med Virol. April 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO.int. Statement on the second meeting of the International Health Regulations . World Health Organization; 2005. Emergency Committee regarding the outbreak of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). [Accessed 25 March 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO.int WHO Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003

- 5.WHO. int. Europe Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV).

- 6.coronavirus.jhu.edu. Mapping 2019-nCoV. Cited January 23, 2020. [Accessed 15 March 2020].

- 7.Lionel Laurent. How to lock down 2.6 billion people without killing the economy Bloomberg

- 8.en.unesc.org. COVID-19 Educational disruption and response. UNESCO. 4 March 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) — United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McIntosh K. Coronaviruses: a Comparative Review. In: Arber W., Haas R., Henle W., Hofschneider P.H., Jerne NK, Koldovský P, editors. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology/Ergebnisse der Mikrobiologie und Immunitätsforschung. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 1974. pp. 85–129. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tyrrell D.A., Bynoe M.L. Cultivation of viruses from a high proportion of patients with colds. Lancet. 1966;1:76–77. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(66)92364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hamre D., Procknow J.J. A new virus isolated from the human respiratory tract. Exper Biol Med. 1966;121:190–193. doi: 10.3181/00379727-121-30734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn J.S., McIntosh K. History and recent advances in coronavirus discovery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:S223–S227. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000188166.17324.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKie Robin. Scientists trace 2002 Sars virus to colony of cave-dwelling bats in China. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/10/sars-virus-bats-china-severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome.

- 15.WHO.int . WHO; April 2020. Novel coronavirus update – new virus to be called MERS-CoV. [Accessed 15 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan J.F., Lau S.K., To K.K., Cheng V.C., Woo P.C., Yuen K.Y. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic beta coronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28:465–522. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00102-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lai M.M., Holmes K.V. Coronaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe D.M., Howley P.M., editors. Fields Virology. Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia, PA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang X., Wu C., Li X., Song Y., Yao X., Wu X. On the origin and continuing evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Sci Rev. 2020;7:1012–1023. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Bo Yang, Wu H. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17:259–260. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lam T.T., Jia N., Zhang Y.W., Shum M.H.H., Jiang J.F., Zhu H.C. Identification of 2019-nCoV related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins in southern China. Nature. 2020;583:282–285. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenberg J. How Scientists Quantify the Intensity of an Outbreak Like COVID-19. https://labblog.uofmhealth.org/rounds/how-scientists-quantify-intensity-of-an-outbreak-like-covid-19.

- 24.“Q&A on coronaviruses”. Vol. 8. World health organization; April 2020. Archived from the original on 20 January 2020. [Accessed 12 April 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H., Holbrook M.G., Gamble A., Williamson B.N. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao F., Tang M., Zheng X., Liu Y., Li X., Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology. 2020;158 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.055. 1831–3.E3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dong L., Tian J., He S., Yang J., Zhu C., Wang J. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected Mother to her Newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–582. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phua J., Weng L., Ling L., Egi M., Lim C.M., Divatia J.V. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506–517. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., Liang W.H., Ou C.Q., He J.X. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu F., Wang A., Liu M., Wang Q., Chen J., Xia S. Neutralizing antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in a COVID-19 recovered patient cohort and their implications. medRxiv. 2020 2020.02.13.945485. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Centers for disease control and prevention. Evaluating and testing persons for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). [Accessed 15 March 2020].

- 34.Young B.E., Ong S.W.X., Kalimuddin S., Low J.G., Tan S.Y., Loh J. Epidemiologic features and clinical course of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore. JAMA. 2020;323:1488–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phua J., Weng L., Ling L., Egi M., Lim C.M., Divatia J.V. Intensive care management of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): challenges and recommendations. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:506–517. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30161-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stockman L.J., Bellamy R., Garner P. SARS: systematic review of treatment effects. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan K., Liu B., Li C., Zhang H., Yu T., Qu J. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:9490–9496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tirado S.M., Yoon K.J. Antibody-dependent enhancement of virus infection and disease. Viral Immunol. 2003;16:69–86. doi: 10.1089/088282403763635465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dainius Pūras, Ahmed Shaheed, Madrigal-Borloz Victor. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner; Geneva. No exceptions with COVID-19: "Everyone has the right to life-saving interventions" – UN experts say. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=25746

- 40.Organization for economic Co-operation and development https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/

- 41.World health organization Solidarity" clinical trial for COVID-19 treatment. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/global-research-on-novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov/solidarity-clinical-trial-for-covid-19-treatments

- 42.Bradley Elizabeth H. Doctors are being Forced to ration care. Don’t blame them. Blame decades of poor U.S. Policy |opinion. https://www.newsweek.com/2020/04/24/doctors-are-being-forced-ration-care-dont-blame-them-blame-decades-poor-us-policy-opinion-1496030.html. [Accessed April 6, 2020].