Abstract

The interaction between the cumulative effect of psychosocial and structural factors (i.e. syndemic effect) and social networks among young Black transgender women and men who have sex with men (YBTM) remains understudied. A representative cohort of 16–29 year-old YBTM (n=618) was assessed for syndemic factors [i.e. substance use; community violence; depression; poverty; justice system involvement (JSI)], social network characteristics, condomless anal sex (CAS), group sex (GS), and HIV-infection. The syndemic index significantly increased the odds of CAS, GS, and HIV-infection, and these effects were moderated by network characteristics. Network JSI buffered the effect on CAS, romantic network members buffered the effect on GS, and network age and proportion of family network members buffered the effect on HIV-infection. The proportion of friend network members augmented the effect on GS and HIV-infection. Future research to prevent HIV among YBTM should consider social network approaches that target both structural and psychosocial syndemic factors.

Keywords: Black, Transgender Women, MSM, HIV, Syndemic

INTRODUCTION

Young Black transgender women and men who have sex with men (YBTM) bear an increasingly disproportionate burden of new HIV infections in the United States (US).(1–5) Between 2008 and 2014, HIV prevalence among young Black men who has sex with men (YBMSM) across 20 American cities increased from 17% to 26%.(6) Black transgender women also are one of the most vulnerable populations to become HIV positive in the US, with an estimated HIV prevalence of 56%.(7) However, compared to other men who have sex with men (MSM), Black MSM (BMSM) are more likely to use condoms during anal sex and less likely to use drugs during sex.(8) Thus, the excessive burden of HIV infection among YBTM is not likely explained solely by individual behavior and may be better explained by psychosocial (i.e., indicators of psychological and social functioning, such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse) and structural factors (e.g., poverty, justice system involvement, unemployment).(3, 8–16) In addition, a growing body of evidence suggests that social network factors (i.e., the number of people in a social network and the characteristics of different network members) may significantly influence vulnerability to HIV infection among YBTM.(17–20) Research on how social network characteristics moderate the relationship between psychosocial and structural factors and HIV transmission-related behaviors and HIV serostatus among YBTM is limited.

Syndemic Theory

Syndemic theory offers an approach to investigate inequities in HIV incidence within a psychosocial and structural framework that remains understudied among YBTM.(13, 21) A syndemic is defined as co-occurring, mutually enhancing epidemic psychosocial factors that exacerbate illness and reinforce health inequities.(22–24) Merrill Singer first described a syndemic of substance abuse, violence and AIDS (SAVA) in a poor urban setting.(23) Stall et al. extended syndemic theory to describe increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among MSM by including psychosocial factors such as depression, childhood sex abuse and partner violence.(22) Further studies have established significant associations between syndemic factors and HIV transmission-related behaviors among young MSM.(25–27) However, applying the MSM syndemic framework to BMSM populations have produced mixed results,(21, 26, 28, 29) which may be because studies rarely incorporate structural factors that are most relevant to BMSM.(13)

As syndemic research has progressed, scholars have highlighted how social and structural factors such as sex work, gender-based violence, and poverty create unique contexts of hyper-vulnerability to HIV among cisgender women.(30–32) Similarly, research examining syndemic conditions among transgender women has demonstrated that syndemics are positively associated with both transactional sex and incarceration.(14, 33) However, prior syndemic research focused on HIV often does not consider structural factors that disproportionately affect YBTM, such as incarceration, poverty and community violence, which may contribute to higher burden of HIV incidence among YBTM.(12–14, 33–41) In two exceptions, Wilson et al. proposed that poverty, incarceration and community violence likely synergistically contribute to increased HIV risk among Black men,(13) and Mizuno et al. included incarceration and homelessness in a syndemic index among people with injection drug use living with HIV.(42)

The analytic approach employed by Wilson et al.(13) and Mizuno et al.(42) is consistent with more recent interpretations of syndemic theory, which focus on both the synergistic clustering of health inequities and social conditions that perpetuate, maintain, and exacerbate health inequities. Including poverty, community violence, incarceration and other indicators of unequal social conditions in syndemic analyses is important given that these factors are disproportionately experienced by Black cisgender and transgender men and women, and tend to have a synergistic impact on health.(13) Poverty, incarceration, and community violence affect Black communities in epidemic proportions. In 2010, the US Census estimated that Black Americans represented 24.2% of people living in poverty, while making up 12.3% of the US population, and that 50.4% of Black Americans lived in areas of concentrated poverty.(43) Also in 2010, Black men and women represented 38.9% of the U.S. prison population, and experienced an imprisonment rate 6.5 times greater than White men and women.(44) From 2009 to 2016, the age-adjusted rates of homicide among 15–29 year old non-Hispanic Black men increased 55.00 to 73.38 per 100,000, whereas the age-adjusted rates of homicide among 15–29 year old non-Hispanic White men remained stable at 3.36 to 4.09 per 100,000 over the same time period.(45) Beyond homicide, from 2015 to 2016 the rate of criminal victimization in urban settings increased from 22.7 to 28.4 per 1,000 people, and victims were more likely to be Black and low-income.(46) A national survey of urban adolescents found that 55% had been exposed to community violence, which was further concentrated among Black adolescents and positively associated with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder.(47) Previous research also has found that exposure to community violence is associated with significantly higher rates of HIV-related transmission behaviors among YBMSM.(37, 48, 49) Importantly, poverty and incarceration are interlinked and independently associated with substance abuse and risk of HIV infection.(34, 36, 50–52) Specifically, housing instability has been associated with justice system involvement(17) and HIV transmission among YBMSM.(53) In addition, poverty and incarceration are two of the leading predictors of HIV infections among YBMSM in the US,(8) and are further concentrated among Black transgender women.(8, 54, 55) Given these data, it is imperative to consider structural factors such as poverty, incarceration and community violence within a syndemic framework in order to understand inequitable vulnerability to HIV infection among YBTM.

Stress, Resilience and Social Networks

Minority stress theory suggests that stigma and discrimination are primary determinants of poor health and mental health among sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations.(56–58) Research investigating minority stress among populations with multiple minority statuses, such as racial, sexual and gender minorities, suggests that discrimination and stigma experienced by YBTM are likely to be unique and different from single minority populations.(59–62) The stress-buffering hypothesis in minority stress theory suggests that resiliency factors, such as social support, community connectedness, and pro-social coping may buffer against minority stressors.(28, 63) As research on the health of SGM populations has grown, several researchers have noted the need for resilience-focused research with MSM and transgender women. For example, Herrick, et al.(64) proposed a resilience framework for prevention research among MSM that identified potential resilience factors at the individual, dyadic, family, and community levels. In addition, Herrick and colleagues recommend that future research utilize moderation analyses, exploring factors such as social support, as a method of testing causal pathways.(64) In one of the few syndemic studies to test the moderating effect of resilience factors, O’Leary et al. found that both optimism and educational status buffered the effect of syndemic conditions on HIV serostatus in a sample of BMSM.(28) More recently, Pitpitan et al. demonstrated “outness” as a buffer of syndemic conditions on HIV risk-taking behavior among MSM in Tijuana, Mexico.(65) However, there is a dearth of research on the moderating effects of social networks on syndemic conditions.

The lack of research on how social networks may exacerbate or buffer the effect of syndemic conditions on HIV among YBTM is surprising given the large body of scholarship implicating social networks in vulnerability to HIV.(18, 66–72) For example, among BMSM, supportive networks have been associated with a lower likelihood of HIV infection(68) and condomless anal sex(69), and a higher likelihood of HIV testing.(69, 70) In addition, studies suggest that the types of nodes in an ego’s network, e.g., the proportion that is family of origin, family of choice, friends, and sexual partners, are related to HIV transmission-related behaviors and HIV serostatus.(67) Furthermore, in our prior work, we found that the proportion of family members in the social networks of YBMSM was associated with less sex-drug use and group sex, and with a higher likelihood of discouraging group sex and sex-drug use.(18) Conversely, negative peer norms about safer sex may lead to riskier sex behaviors,(73, 74) and lack of social support may mediate sex work among Black men.(72) The presence of “enablers”, network members who do not disapprove of engaging in risk behaviors, within a social network may increase the likelihood of condomless anal sex among Black MSM.(71) In addition, network HIV viral load has been demonstrated to be associated with increased HIV seroprevalence among YBTM.(75) Beyond HIV transmission risk factors, social network characteristics also have been closely tied to psychosocial and structural factors such as housing,(76) substance abuse,(72) and incarceration.(17)

The Present Study

The current study examines the syndemic effect of both psychosocial and structural factors on HIV transmission-related behaviors and HIV infection, and the potential moderating effect of social network factors in a representative sample of YBTM. The study has several aims. First, we aimed to characterize a syndemic index of psychosocial and structural factors that are relevant to YBTM and that significantly impact HIV infection and HIV transmission-related behaviors, i.e., condomless anal sex and group sex. Our second objective was to investigate social network characteristics as potential moderators of the association between the syndemic index and our three HIV-related outcomes of interest. Because prior research has found that YBTM tend to be embedded in homophilous social networks, it is plausible that network members are also subjected to syndemic conditions that can affect vulnerability to HIV among YBTM.(17, 71) To test this possibility and further extend the research base on syndemic conditions and social networks, we created and examined the moderating effect of a network syndemic indicator. Lastly, we sought to replicate findings by O’Leary et al.(28) by testing if respondents’ education moderated the association between the syndemic index and HIV-related outcomes.

Based on the extant research, we hypothesized that community violence, poverty, history of justice system involvement (JSI), illicit substance use (ISU) and depression would be significantly mutually enhancing, supporting their inclusion in the syndemic index. We next hypothesized that a syndemic index consisting of psychosocial and structural factors would be associated with a higher odds of HIV infection and HIV transmission-related behaviors among YBTM. We hypothesized that larger social networks, and networks including more members who are friends, family, male or older, would buffer the effect of syndemic index on HIV-related outcomes. Conversely, we anticipated that social networks with more members with JSI, ISU, or who are romantic or HIV seropositive would exacerbate the effect of the syndemic index on HIV-related outcomes. In addition, we hypothesized that the number of syndemic factors within social networks would exacerbate the effect of the syndemic index on HIV-related outcomes. Finally, we expected that higher educational achievement among index respondents would operate as a protective factor and buffer YBTM against the negative effects of syndemic factors.

METHODS

Setting and population

We analyzed baseline data from the uConnect study, a longitudinal population-based cohort of YBTM in Chicago that aims to examine how social and sexual networks impact the risk of sexually transmitted infections among YBTM, including HIV. Chicago is home to one of the largest contiguous geographic communities of Black American residents in the United States.(77) The role of violence is particularly salient in cities like Chicago, which have a long history of racial segregation and disinvestment in majority Black American neighborhoods; in Chicago, this has contributed to place-based poverty and community violence on the South and West Sides of the city.(78, 79)

Study participants

Eligibility criteria

Study respondents were eligible if they 1) self-identified as Black or African American, 2) were assigned male sex at birth and currently identify as a male or as a transgender woman, 3) were 16 to 29 years old, 4) reported oral or anal sex with a male within the past 24 months, 5) were residing on the South Side of Chicago, and 6) were willing and able to provide informed consent.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Recruitment and data collection procedures for the uConnect study have been previously described.(17, 19, 71) Briefly, respondent driven sampling (RDS) was used to recruit a diverse group of YBTM between June 2013 and June 2014. A total of 62 seeds were recruited via various venues (i.e. House/Ball community, Facebook, community events, college campuses, etc.) and invited to recruit other eligible YBTM. Participants were offered $60 for completing the interview and $20 for each additional recruit. Interviews were conducted using Computer Aided Personal Interviewing.

Measures

Outcomes.

HIV infection was determined by 4th generation HIV immunoassay (Abbott ARCHITECT HIV Ag/Ab Combo assay), HIV-1/−2 Ab differentiation (Bio-Rad Multispot HIV-1/−2 Rapid Test). Condomless sex with male or transgender partner(s) in the last 6 months (CAS), and group sex in the past 12 months (GS) were self-reported (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Psychosocial and structural syndemic factors.

Psychosocial and structural syndemic factors were self-reported and included: 1) illicit substance use (ISU), 2) depression, 3) lifetime history of being a victim of community violence, 4) justice system involvement (JSI) and 5) poverty. ISU was assessed as using ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics or methamphetamines in the past 12 months (marijuana and alcohol were not included). Depressive symptoms were determined using the Brief Symptom Inventory-18 depression subscale T-score; participants with a T-score > 62 were considered to have depression.(80) Community violence was assessed using the Community Violence Probe,(81) a questionnaire previously validated with young Black men(17, 37, 82) that evaluates the number of times (range: 0 to ≥ 6) respondents experience violence, witness violence, and have friends and family who are victims of violence (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88). Following previous studies,(17, 37) we calculated raw scores by taking the means of all the item scores and then converted the raw scores to T-scores. Respondents with a T-score greater than or equal to the median were considered to have a lifetime history of community violence. JSI was assessed by asking participants, “Have you ever been detained, arrested, or spent time in jail or prison?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). Similar to a measure of poverty developed by Mena et al. that was previously associated with HIV risk among YBMSM,(50) poverty was defined as not having enough money in the household for rent, food, or utilities in the last 6 months or being homeless in the past 12 months. The syndemic index (range: 0 to ≥ 4) was calculated for each respondent by summing the presence of 5 psychosocial and structural factors: ISU, depression, history of community violence, poverty and JSI.

Social network characteristics.

Participants listed up to 5 members of their close and personal social network, defined as “people with whom you discuss things that are important to you.” After populating their network, each participant described the type of relationship, age, gender, HIV serostatus, JSI and ISU of each network member. Type of relationship was categorized as friend, romantic (i.e. spouse, current or ex-romantic partner, or non-romantic sex partner), family (i.e. play, made-up, by blood, or by marriage), or other (i.e. co-worker, neighbor, housemate, minister, teacher, doctor, or counselor). Participants also reported the HIV serostatus of each network member, how often a network member used illicit substances (0 = never or less than once a year, 1 = at least once a year), and whether they had ever been detained, arrested, or spent time in jail/prison (0 = no, 1 = yes). Older social network member age was defined as being at least 1 year older than respondents (0 = no, 1 = yes), and peer social network members was defined as aged within 1 year (older or younger) of respondents (0 = no, 1 = yes). Similar to previous studies, we calculated the proportion and number of network members with each characteristic within each respondent’s social network.(71, 83) In addition, we calculated a social network syndemic index by summing the presence of ISU and JSI within each respondent’s social network (0 = no presence of social network ISU or JSI; 1 = presence of social network ISU or JSI; 2 = presence of social network ISU and JSI).

Social-demographic factors.

Respondents reported their age, sexual orientation, transgender identity, educational achievement, employment status and healthcare coverage. For respondents who were HIV seropositive we calculated days since HIV diagnosis, and for respondents with JSI we calculated total days spent in the justice system. Transgender identity was determined using the two-step method described by Reisner, et al.(84)

Analysis

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (R Version 3.5.2). Exploratory analyses indicated that some variables had missing data at up to 3.6%. We used the Survey Package in R to conduct logistic regression, and treated missingness by list-wise deletion.(85) Logistic regression models were weighted using Gile’s sequential sampling estimator, which treats RDS as a successive sampling process of a known or reliably estimated population.(86) In the present study, we used Livak et al.’s estimation that there are 5,500 YBMSM in the catchment area.(87) Following syndemic theory, in order to examine if psychosocial and structural factors were mutually enhancing, we conducted a series of bivariate logistic regressions between each syndemic factor. We also conducted bivariate logistic regression between psychosocial and structural factors and outcomes of interest. In order to test for a cumulative syndemic effect, we next completed binomial multivariate logistic regression with the syndemic index as the independent variable and CAS, GS or HIV infection as a dependent variable. Because HIV diagnosis(76) and JSI (17, 19, 37) have been shown to impact social networks of YBMSM, we included time since HIV diagnosis and time spent in the justice system in days in our modeling. Age, HIV serostatus, time since HIV diagnosis and time spent in the justice system were included a priori in modeling of behavioral outcomes. Age and time spent in the justice system were included a priori in modeling of HIV infection. Covariates included in modeling were education, employment status, sexual orientation, transgender identity and health care insurance status. Goodness-of-fit was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and models with lower values indicated better fit.(88)

To examine if social networks characteristics moderated the association between the syndemic index and the dependent variables, we used methods described by Baron and Kenny.(89) We tested the significance of interactions between the syndemic index and social network characteristics (size, age, gender, relationship, ISU, JSI, and social network syndemic index), as well as respondent education, for each outcome. Social network variables included two dichotomous variables, ≥ 50% vs. < 50% of network with a given characteristic and ≥ 1 member vs. none with a given characteristic. We created probability plots and calculated adjusted odds ratios stratified by social network characteristics with significant moderator effects. We tested for multicollinearity using variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis with a threshold value of 10.(90) When VIF score exceeded 10, we centered the syndemic index to determine if there was a difference. Finally, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with unweighted models.

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics.

Socio-demographic, psychosocial and structural factors of the 618 respondents included in the study population are described in Table 1. Transgender women comprised 9% of the sample. The median age was 23 [interquartile range (IQR) 20, 25] and most respondents (66%) identified as gay. The median number of social network members was 2 (IQR 2, 3). More than half of the study population (61%) had achieved education beyond high school, 48% were unemployed and 46% did not have healthcare coverage. Structural syndemic factors were prevalent: 51% reported a history of community violence, 46% reported justice system involvement (JSI) and 53% reported poverty. Psychosocial syndemic factors, such as depression (12%) and illicit substance use (ISU) (18%), were less prevalent. Community Violence Probe measures demonstrated that 65% reported being a victim of violence, 83% reported having a close friend robbed or attacked, 71% witnessed someone being beaten and 57% witnessed gun related violence. Most study participants (84%) reported at least 1 syndemic factor, and 57% reported 2 or more syndemic factors. There also was a high prevalence of HIV infection, with 34% being HIV seropositive. In addition, 21% reported group sex (GS) and 48% reported condomless anal sex (CAS).

Table I:

Description of study participant characteristics from the uConnect study cohort of young Black MSM and transgender women in Chicago, 2014 (n = 618)

| % (N)a | |

|---|---|

| Median number of social network members (IQR) | 2 (2, 3) |

| Median age (IQR) | 23 (20, 25) |

| Other | 3 (19) |

| Transgender identity | 9 (54) |

| Undergraduate or graduate degree | 16 (97) |

| Full time (≥30 hours/week) | 25 (152) |

| Healthcare coverage | 54 (332) |

| Illicit substance use in the past 12 monthsc | 18 (110) |

| Depressiond, e | 12 (71) |

| History of community of violenceb | 51 (316) |

| History of justice system involvementb | 46 (285) |

| Povertyf | 53 (327) |

| HIV Diagnosis | 34 (210) |

| Condomless Sex with male or transgender partner(s) in last 6 months | 48 (299) |

| Group sex in the past 12 monthsa | 21 (128) |

| ≥ 4 | 9 (54) |

IQR = interquartile range

Except where otherwise noted.

Missing 1 due to incomplete data.

Ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics, methamphetamines.

Missing 22 due to incomplete data.

Brief Symptom Inventory depression subscale t score > 62.

Not having enough money in the household for rent, food, or utilities in the last 6 months or being homeless in the last 12 months.

Presence of 5 psychosocial and structural factors (illicit substance use, depression, history of community violence, poverty, history of justice system involvement).

Respondents reported the characteristics of 1566 social network members (see Table 2). Social networks consisted mostly of friends and family who were male and older, with a median age of 27 (IQR 22.75, 33.42). Among respondents, 80% had ≥ 1 older member, 61% had ≥ 1 peer member, 81% had ≥ 1 male member, 68% had ≥ 1 friend, 59% had ≥ 1 family member, and 32% had ≥ 1 romantic member. Social network ISU was not common, with 12% of respondents with ≥ 1 member with ISU; however, 49% of respondents had ≥ 1network member with JSI and 21% had ≥ 1 HIV-positive network member.

Table II:

Description of social network characteristics among participants from the uConnect study cohort of young Black MSM and transgender women in Chicago, 2014

| Social network characteristic | Median (IQR) proportiona | Median (IQR) counta |

|---|---|---|

| Ageb | 27.00 (22.75, 33.42) | 24 (21, 31) |

| ≥1 year older | 0.60 (0.33, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) |

| Peer c | 0.33 (0.00, 0.50) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Male | 0.50 (0.33, 1.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) |

| HIV + | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Illicit substance used | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) |

| Justice system involvement | 0.00 (0.00, 0.50) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Romantic | 0.00 (0.00, 0.33) | 0.00 (0.00, 1.00) |

| Friend | 0.50 (0.00, 0.75) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) |

| Family | 0.33 (0.00, 0.60) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.75) |

| 2 | 9 (59) | |

IQR = interquartile range

Statistics are reported as per respondent (n = 618) except where otherwise noted.

Among all social network members (n = 1566).

Within 1 year of respondent’s age.

Illicit substance use (ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics, methamphetamines) in last year.

Presence of 0, 1, or 2 psychosocial or structural factors (ISU; JSI) within respondents’ social network.

Syndemic conditions.

Bivariate association in-between psychosocial and structural factors, and between those factors and outcomes are described in Table 3. The adjusted odds ratio of the syndemic index on HIV infection and HIV-related transmission behaviors are shown in table 4. Consistent with our hypothesis, the syndemic index was significantly associated with an increased odds of HIV infection [adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 1.31, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 1.08–1.60, p < 0.01], GS (aOR 1.28, 95% CI 1.00–1.63, p = 0.04) and CAS (aOR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09–1.57, p < 0.001), when controlling for confounding factors.

Table III:

Bivariate association between psychosocial factors, structural factors, HIV infection, condomless sexe and group sexf

| ISUa | Depressionb | Community violencec | JSIc | Povertyd | HIV infection | Condomless sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depressionb | 3.03 (1.51, 6.11)** |

||||||

| Community violencec | 1.84 (1.02, 3.32)* |

1.48 (0.80, 2.75) |

|||||

| JSIc | 4.09 (2.27, 7.36)*** |

1.90 (1.01, 3.59)* |

2.19 (1.45, 3.32)*** |

||||

| Povertyd | 1.30 (0.72, 2.34) |

3.17 (1.58, 6.36)** |

1.88 (1.24, 2.85)** |

2.15 (1.42, 3.25)*** |

|||

| HIV infection | 2.10 (1.16, 3.79)* |

1.55 (1.00, 2.42)** |

0.86 (0.55, 1.35) |

1.95 (1.25, 3.03)** |

1.90 (1.01, 3.59)* |

||

| Condomless sexe | 2.00 (1.10, 3.61)** |

1.19 (0.79, 1.79) |

1.08 (0.72, 1.63) |

1.58 (1.05, 2.38)* |

1.35 (0.73, 2.52) |

2.10 (1.35, 3.28)** |

|

| Group sexf | 3.96 (2.11, 7.46)*** |

1.17 (0.69, 1.98) |

0.87 (0.5261, 1.48) |

2.25 (1.33, 3.80)** |

2.06 (1.05, 4.02)* |

1.85 (1.08, 3.20)* |

1.59 (0.94, 2.68) |

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001

JSI = Justice system involvement

ISU = Illicit substance use.

Illicit substances include ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics and methamphetamines in past 12 months.

Brief Symptom Inventory subscale t score > 62.

Lifetime history.

Not having enough money in the household for rent, food, or utilities in the last 6 months or being homeless in the last 12 months.

With male and transgender partner(s) in last 6 months.

In the past 12 months.

Table IV:

Adjusted odds ratio of HIV infection and HIV transmission-related behaviors by syndemic index score and moderation by social network characteristics

| HIV infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1g: Direct (no moderator) |

Model 2h: Frienda as moderator |

Model 3h: Ageb as moderator |

Model 4h: Familyc as moderator |

|

| Syndemic index | 1.31 (1.08, 1.60)** | 1.06 (0.80, 1.40) | 1.99 (1.31, 3.01)** | 1.63 (1.28, 2.06)*** |

| Syndemic index [x] Friend(s)a | 1.66 (1.13, 2.43)** | |||

| Friend(s)a | 0.26 (0.11, 0.59)** | |||

| Syndemic index [x] Ageb | 0.60 (0.38, 0.96)* | |||

| Ageb | 4.08 (1.52, 10.96)** | |||

| Syndemic index [x] Familyc | 0.64 (0.43, 0.96)* | |||

| Familyc | 2.63 (1.11, 6.26)* | |||

| Group sex in the past 12 months | ||||

| Model 1ai: Direct (no moderator) |

Model 2aj: Friendd as moderator |

Model 3aj: Frienda as moderator |

Model 4aj: Romantice as moderator |

|

| Syndemic index | 1.28 (1.00, 1.63)* | 0.85 (0.55, 1.32) | 0.97 (0.66, 1.42) | 1.41 (1.06, 1.89)* |

| Syndemic index [x] Friend(s)d | 1.80 (1.11, 2.93)* | |||

| Friend(s)d | 0.50 (0.18, 1.40) | |||

| Syndemic index [x] Friend(s)a | 1.64 (1.04, 2.57)* | |||

| Friend(s)a | 0.65 (0.24, 1.76) | |||

| Syndemic index [x] Romantice | 0.64 (0.41, 1.00)* | |||

| Romantice | 2.21 (0.83, 5.89) | |||

| Condomless sex with a male or transgender partner in the past 6 months | ||||

| Model 1bk: Direct (no moderator) |

Model 2bl: JSIf as moderator |

|||

| Syndemic index | 1.31 (1.09, 1.57)*** | 1.56 (1.21, 2.01)*** | ||

| Syndemic index [x] JSIf | 0.67 (0.47, 0.96)* | |||

| JSIf | 2.15 (1.00, 4.63)* | |||

Goodness-of-fit for all models was assessed using Akaike Information Criterion.

p ≤ 0.05;

p ≤ 0.01;

p ≤ 0.001

JSI = Justice System Involvement.

ISU = illicit substance use (ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics, methamphetamines) in past 12 months.

Syndemic Index = presence of 0, 1, 2, 3, ≥ 4 psychosocial and structural factors (ISU, depression, history of community of violence, history of JSI, and poverty) among respondents.

≥ 50% of social network is friends.

≥ 1 social network member who is ≥ 1 year older.

≥50% of social network is family (blood or play).

≥ 1 friend in social network.

≥ 1 romantic members in social network.

≥ 1 member with JSI in social network.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, sexual orientation, transgender identity.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, sexual orientation, transgender identity, days spent in the justice system.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV diagnosis (HIV dx), transgender identity.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV dx, transgender identity, days in the justice system, days since HIV dx.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV dx, sexual orientation, education, employment status.

Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV dx, sexual orientation, education, employment status, days in the justice system, days since HIV dx.

Moderator results.

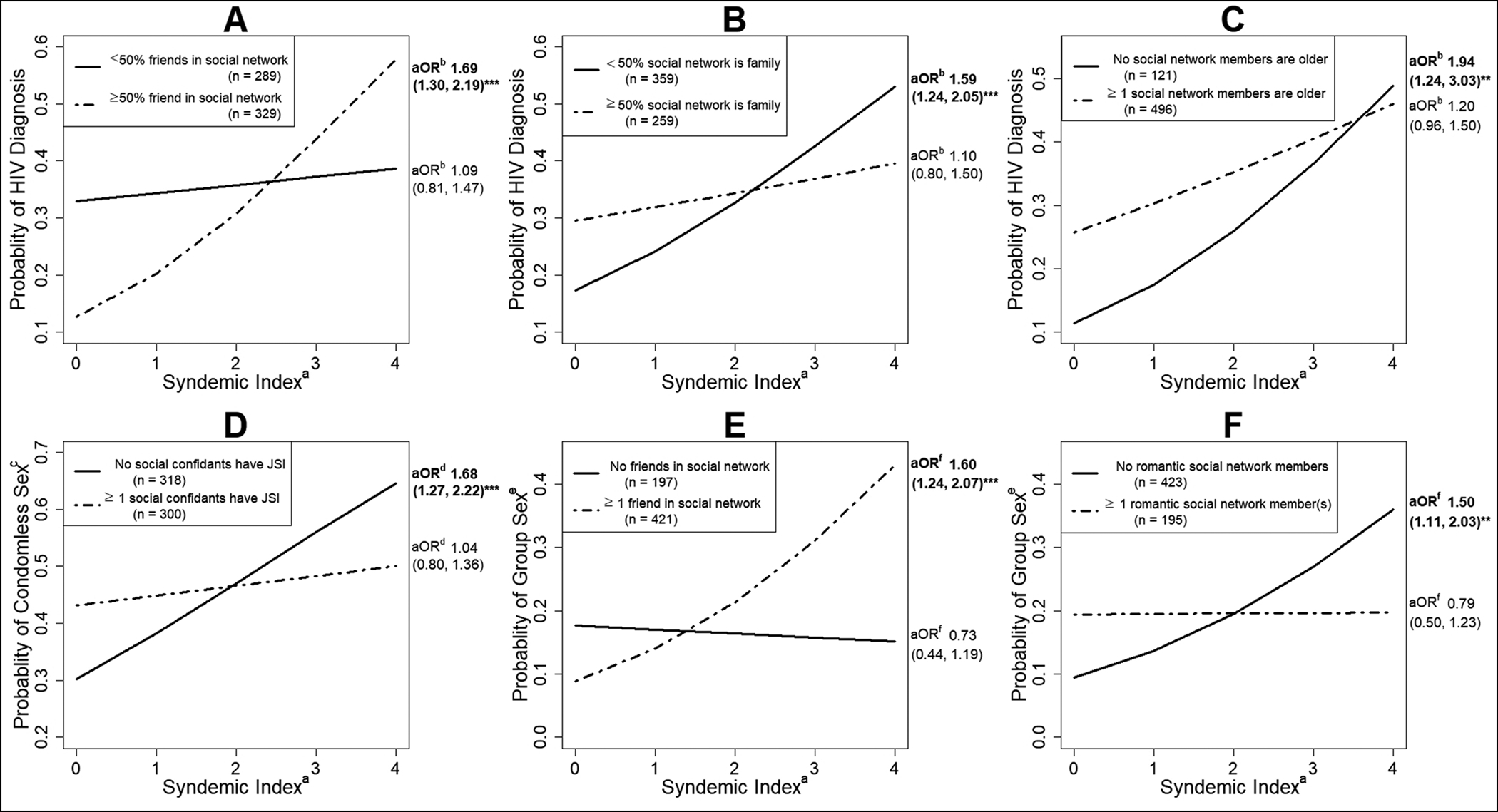

Significant moderation effects by social network characteristics are shown in Table 4. As hypothesized, the syndemic effect on HIV infection was buffered by social networks that consisted of more family members (< 50% vs. ≥ 50% aOR 0.64, 95% CI 0.43–0.96, p = 0.03, Figure 1B) and social networks with ≥ 1 older members (aOR 0.60, 95% CI 0.38–0.96, p = 0.03; Figure 1C). Contrary to our hypothesis, we found that the syndemic effect on HIV infection was augmented by social networks with a greater proportion of friends (< 50% vs ≥ 50% aOR 1.66, 95% CI 1.13–2.43, p < 0.01, Figure 1A).

Figure 1: Predicted probabilities and adjusted odds ratios by syndemic index and stratified social network characteristics.

** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001

ISU = Illicit substance use (ecstasy, volatile nitrates, cocaine/crack, heroin, psychedelics or methamphetamines) in past 12 months.

JSI = Justice system involvement.

a. Presence of 1, 2, 3, ≥ 4 psychosocial and structural factors (ISU, depression, history of community violence, history of JSI, and poverty) among respondents.

b. Adjusted for respondent’s age, sexual orientation, transgender identity, days spent in the justice system.

c. Condomless sex with male or transgender partner(s) in the last 6 months.

d. Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV dx, sexual orientation, education, employment status, days in the justice system, days since HIV diagnosis.

e. Group sex in the past 12 months.

f. Adjusted for respondent’s age, HIV dx, transgender identity, days in the justice system, days since HIV dx.

We also found a significant interaction between the syndemic index and social network characteristics on HIV transmission-related behaviors. Contrary to our hypothesis, the syndemic effect on GS increased among respondents with more friends in their social network (0 vs ≥ 1 aOR 1.80, 95% CI 1.11–2.93, p = 0.01, Figure 1E; < 50% vs ≥ 50% aOR 1.64, 95% CI 1.04–2.57, p = 0.03), and buffered among respondents with more romantic network members (0 vs ≥ 1 aOR 0.64, 95% CI 0.41–1.00, p = 0.05, Figure 1F). Also, unexpectedly, the syndemic effect on CAS was buffered by having more social network members with JSI (0 vs ≥ 1 aOR 0.67, 95% CI 0.47–0.96, p = 0.05, Figure 1D). The social network syndemic index had a significant buffering effect on the relationship between the respondent syndemic index and CAS (aOR 0.71, 95% CI 0.54–0.94, p = 0.02). We did not find any significant interactions between the syndemic index and social network size, ISU or HIV status. Lastly, respondent education did not moderate the effect of the syndemic index on HIV-related outcomes.

Sensitivity analyses.

Centering the syndemic index did not change results, and the unweighted analysis demonstrated significant bivariate and multivariate results (see Supplemental Tables I and II). The unweighted models demonstrated significant increase in the association between syndemic index and HIV infection among respondents with more transgender network members (0 vs ≥ 1 aOR 2.01, 95% CI 1.02–3.96, p = 0.04; < 50% vs ≥ 50% aOR 8.09, 95% CI 1.43–45.87, p = 0.02). Also, in the unweighted models, there was no significant moderation of the association between syndemic index and GS or CAS.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the relationship between syndemic factors and social networks on HIV serostatus and HIV-related transmission behaviors among YBTM. A syndemic index inclusive of psychosocial and structural factors relevant to YBTM was significantly associated with an increased odds of HIV infection, engaging in group sex in the past 12 months (GS), and reporting condomless anal sex in the past 6 months (CAS). Moderation analysis demonstrated that various social network characteristics, including age, gender, justice system involvement (JSI), number of friends, number of romantic members and family proportion, significantly moderated the syndemic effect on HIV infection and behavioral outcomes. Overall, psychosocial, structural and social network factors contribute to significant variability in HIV-related outcomes in this study population. This study advances the understanding of the interplay between social networks and syndemic psychosocial and structural factors among YBTM and can inform future research and HIV prevention efforts.

For every additional syndemic factor there was a 31% increased odds of HIV infection, 31% increased odds of CAS and 28% increased odds of GS. Whereas previous syndemic studies among YBTM have limited syndemic indices to psychosocial factors, such as mental health, substance abuse and childhood or sexual violence,(22, 25, 26) this study included incarceration, poverty and community violence, which are structural factors that disproportionately affect YBTM in the US.(12, 13, 34–38, 48, 51, 54, 55, 91) Among Black MSM across 6 US cities, an estimated 60% have reported being incarcerated during their lifetime,(51) and 39% were in financial crisis.(34) In comparison, approximately half of respondents had JSI, reported poverty or were unemployed. Poverty has been shown to moderate the effect of psychosocial factors on HIV infection.(92) This is one of the first studies to demonstrate that poverty, JSI, and community violence mutually enhance psychosocial and structural factors to synergistically increase HIV risk among YBTM.

Prior syndemic studies have included sexual, childhood and intimate partner violence,(22, 25, 26) but community violence has been overlooked. This study adds to the extant literature by assessing community violence exposure and found that 51% of participants experienced community violence. Likewise, prior Chicago-based research found that 56% of Black male high school students experienced being mugged or robbed.(82) In this study, syndemic factors such as substance abuse and depression were less prevalent than community violence, poverty and JSI, which may explain why previous studies have failed to consistently observe a syndemic effect on HIV risk among YBMSM.(21, 26, 28) The SAVA syndemic described by Singer was adapted to include mental health among MSM,(22, 23) and studies of syndemic factors among women and transwomen have incorporated transactional sex and incarceration.(32, 33) Our findings suggest that it may be necessary to consider JSI, poverty and community violence to comprehensively address the syndemic effect on vulnerability to HIV infection among YBTM.

We presented new findings of social network characteristics moderating the syndemic effect of psychosocial and structural factors on HIV risk among YBTM. The social network characteristics that significantly moderated syndemic effect included the number and proportion of friends, proportion of family, proportion of network members with JSI, the number of older network members, and the number of romantic network members. Interestingly, the proportion of friends in respondents’ networks had a significant positive moderation effect on the relationship between syndemic index and HIV infection. One possible explanation is that friends may promote social norms that encourage HIV-related transmission behaviors, such as CAS.(93, 94) This explanation would be consistent with the concept of homophily in social networks, where respondents may be more likely to exhibit similar behaviors as their social network.(95) The presence of an “enabler,” defined as a close network member who does not disapprove of risky behaviors, in the social networks of YBMSM has been positively associated with HIV-related transmission behaviors.(71) Our findings support both explanations for why friends amplify the association between syndemic and HIV infection. Results documented that having at least one network member who was a friend strengthened the association between the syndemic index and GS, which is consistent with the concept of an “enabler.” It is possible that the moderating impact of friends is secondary to engaging in sexual risk behaviors with friends. However, we found that having ≥ 1 romantic network member buffered the syndemic effect on GS, which makes this unlikely. In the present study, we did not ask whether network members engaged in group sex or condomless anal sex, or the extent to which members approved or disapproved of respondents engaging HIV-related transmission behaviors. Future research should further elucidate the role of friends in social networks of YBTM and how they may impact HIV risk.

In contrast, the syndemic effect on HIV infection was buffered when networks consisted of ≥ 50% family members. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating that greater family proportion in the social networks of Black MSM is associated with a decreased likelihood of engaging in HIV-related transmission behaviors.(18) Family may provide emotional and instrumental support that may result in greater psychological well-being and less unmet needs,(96, 97) and buffer the syndemic effect on HIV risk. A growing body of research suggests that the family members of YBTM may enact specific behaviors, such as HIV testing and disclosure of same-sex behavior, that are significantly associated with HIV risk.(98–100) Importantly, our definition of family was inclusive of family of choice, and not necessarily kin, which may be indicative of connections to the larger YBTM community. Prior analyses with YBMSM has shown that stronger affiliations with the Black community are associated with greater HIV protective behaviors while stronger affiliations with the gay community are correlated with higher rates of sexual behaviors and reporting being HIV positive.(101) Consistent with this trend, social network interventions engaging family members have been associated with better engagement in care among YBTM living with HIV.(20) In our sample, 59% of respondents reported having at least one family member in their social network. These findings support the need for family-based network approaches to HIV prevention among YBTM.

Results also documented that having older social network members buffered the syndemic effect on HIV infection. This finding highlights a distinction from sexual networks, where increasing age has been positively associated with HIV risk.(102–104) While some studies have suggested that Black MSM may be less likely to disclose homosexuality,(9) Latkin et al. found that Black MSM were more likely to disclose their HIV status and same-sex behavior to social network members who are older, or who provide emotional and financial support.(105) In turn, “outness” has been shown to buffer the effect of syndemic factors on HIV risk,(65) which may explain our findings. Most of our study population had at least one social network member who was older, which may represent an untapped resource. Future research should continue to examine disclosure of MSM behavior among YBTM, and the influences exerted by older social network members and family in YBTM’s networks.

Approximately half of respondents had at least 1 social network member with a history of JSI, and we found that having at least 1 social network member with JSI buffered the syndemic effect on CAS. While incarceration has been associated with increased HIV risk,(8, 54, 55) there has been conflicting evidence about the association between incarceration and CAS.(34, 93) Underhill et al.’s review of HIV prevention interventions in incarceration settings found up to 11 programs that reduced sexual risk taking.(106) Thus, social network members with JSI may be more likely to participate in effective HIV prevention interventions compared to those without JSI. In addition, previous analyses of the uConnect cohort demonstrated significant homophily between respondent and social network JSI.(17, 19) Thus, social networks with JSI may be more homophilous and more likely to disseminate behavioral norms that promote safe sex practices, such as condom use, which may explain this finding.

This study introduced a novel measure of social network syndemic index, and the number of syndemic factors within social networks also buffered the relationship between the syndemic index and CAS. However, our social network syndemic index was limited to JSI and illicit substance use (ISU), and very few respondents reported social network ISU without social network JSI (data not shown). Thus, the moderation effect of social network syndemic was likely attributable to social network JSI. Future studies may build on our findings, and further investigate the influence of social network syndemic index on risk of HIV infection. Lastly, unlike O’Leary et al,(28) respondent education did not moderate syndemic effect on HIV risk among our study population. However, this analysis focused on a younger population, which suggests that the buffering effect of education on syndemic factors may be more prominent among older BMSM.

This study should be considered in the context of its limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study that does not allow for causal implications. However, the moderation analysis is hypothesis generating and suggests potential pathways of influence that should be evaluated in future longitudinal research. Respondents were limited to reporting up to 5 social network members, which may influence the accuracy of social network characteristics. However, 90% of respondents reported 4 or less social network members (data not shown), so limiting social networks to 5 members unlikely impacted our results. We did not evaluate participation in larger networks, such as house balls, which may influence behavioral norms and risk of HIV infection among YBTM(107) and may be elucidated by future research. Though commonly used in behavioral research, major analyses relied on self-report measures, which are subject to social desirability bias that may result in underreporting of factors such as JSI and substance use. As in all social network elicitation research, respondents may not have full knowledge about social network members’ HIV status or risk behaviors. However, individual risk behaviors are likely influenced by perceptions of network members’ behaviors regardless if those perceptions are accurate.(108–110) Analyses included combined YBTM given the fluidity of gender identity and sexual orientation at this younger age that was observed in the cohort (data not shown), as well as that most Black TGW having gay or bisexual identities and limited access to gender affirming medical treatment pre-puberty. Lastly, sensitivity analysis with unweighted models produced significantly different results. The current study utilized RDS in order to evaluate YBTM who are often underrepresented in HIV research, and RDS can lead to bias.(86) We applied Gile’s sequential sampling estimator with a reliable estimate of YBMSM on the South Side of Chicago in order to control for RDS bias. We would caution comparison to studies that do not use RDS, as there may be differences in study populations. For example, our study population included 9% (N = 54) transgender women compared to 5–7% in studies of YBTM that did not use RDS.(54, 55) Thus, our population was likely representative of YBTM on the South Side of Chicago, but may not be generalizable to other populations or studies that do not use RDS. Future studies may improve on RDS methodology in order to accurately evaluate risk of HIV infection among YBTM.

Conclusion

Our findings from this population-based sample of YBTM indicate that psychosocial and structural factors have a syndemic effect on HIV risk, and this effect is moderated by several social network characteristics. More specifically, this study highlights the importance of including incarceration, poverty and community violence as syndemic factors that contribute to increased HIV risk among YBTM. Future syndemic research should include those psychosocial and structural factors most relevant to the population of interest, as this information can be used to develop effective HIV prevention programs. Our findings also suggest that social network characteristics likely contribute to significant variability of syndemic effects on HIV risk among YBTM. Given the disproportionately high burden of HIV among YBTM, future research should further clarify which social network characteristics contribute to resilience versus vulnerability among YBTM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to recognize the study participants who provided significant time and insight into their lives. In addition, the authors would like to recognize the staff at the Chicago Center for HIV Elimination, as well as Phil Schumm, Britt Livak, Ethan Morgan and Rita Rossi-Foulkes. This work received funding from the National Institutes of Health grants 1R01DA033875 and R01DA039934. This publication was made possible with help from the Third Coast Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded center (P30 AI117943).

References:

- 1.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wejnert C, Hess KL, Hall HI, Van Handel M, Hayes D, Fulton P Jr., et al. Vital Signs: Trends in HIV Diagnoses, Risk Behaviors, and Prevention Among Persons Who Inject Drugs - United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(47):1336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koblin BA, Mayer KH, Eshleman SH, Wang L, Mannheimer S, del Rio C, et al. Correlates of HIV acquisition in a cohort of Black men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV prevention trials network (HPTN) 061. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Gay and Bisexual Men [Fact Sheet] February 2017. [

- 5.Garofalo R, Hotton AL, Kuhns LM, Gratzer B, Mustanski B. Incidence of HIV Infection and Sexually Transmitted Infections and Related Risk Factors Among Very Young Men Who Have Sex With Men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(1):79–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wejnert C, Hess KL, Rose CE, Balaji A, Smith JC, Paz-Bailey G, et al. Age-Specific Race and Ethnicity Disparities in HIV Infection and Awareness Among Men Who Have Sex With Men--20 US Cities, 2008–2014. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(5):776–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herbst JH, Jacobs ED, Finlayson TJ, McKleroy VS, Neumann MS, Crepaz N, et al. Estimating HIV prevalence and risk behaviors of transgender persons in the United States: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WLt, Wilson PA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millett GA, Flores SA, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Explaining disparities in HIV infection among black and white men who have sex with men: a meta-analysis of HIV risk behaviors. AIDS. 2007;21(15):2083–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(6):1007–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, et al. HIV among Black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: a review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Johnson A, Emerson E. Exploring factors that underlie racial/ethnic disparities in HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2010;87(2):318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson PA, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack EM, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Latino men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brennan J, Kuhns LM, Johnson AK, Belzer M, Wilson EC, Garofalo R, et al. Syndemic theory and HIV-related risk among young transgender women: the role of multiple, co-occurring health problems and social marginalization. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):1751–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauermeister JA, Goldenberg T, Connochie D, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Stephenson R. Psychosocial Disparities Among Racial/Ethnic Minority Transgender Young Adults and Young Men Who Have Sex with Men Living in Detroit. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):279–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, Harper GW. Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(3):230–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider JA, Lancki N, Schumm P. At the intersection of criminal justice involvement and sexual orientation: Dynamic networks and health among a population-based sample of young Black men who have sex with men. Soc Networks. 2017;51:73–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider J, Michaels S, Bouris A. Family network proportion and HIV risk among black men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(5):627–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider J, Cornwell B, Jonas A, Lancki N, Behler R, Skaathun B, et al. Network dynamics of HIV risk and prevention in a population-based cohort of young Black men who have sex with men. Network Science. 2017;5(3):381–409. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouris A, Jaffe K, Eavou R, Liao C, Kuhns L, Voisin D, et al. Project nGage: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial of a Dyadic Network Support Intervention to Retain Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men in HIV Care. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3618–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dyer TP, Shoptaw S, Guadamuz TE, Plankey M, Kao U, Ostrow D, et al. Application of syndemic theory to black men who have sex with men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2012;89(4):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer M AIDS and the health crisis of the U.S. urban poor; the perspective of critical medical anthropology. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(7):931–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, Siconolfi DE, Storholm ED, Solomon TM, Bub KL. Measurement model exploring a syndemic in emerging adult gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(2):662–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007;34(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mustanski B, Phillips G 2nd, Ryan DT, Swann G, Kuhns L, Garofalo R. Prospective Effects of a Syndemic on HIV and STI Incidence and Risk Behaviors in a Cohort of Young Men Who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Herrick A, Stall R, Egan J, Schrager S, Kipke M. Pathways towards risk: syndemic conditions mediate the effect of adversity on HIV risk behaviors among young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):969–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Leary A, Jemmott JB 3rd, Stevens R, Rutledge SE, Icard LD. Optimism and education buffer the effects of syndemic conditions on HIV status among African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2080–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chandler CJ, Bukowski LA, Matthews DD, Hawk ME, Markovic N, Egan JE, et al. Examining the Impact of a Psychosocial Syndemic on Past Six-Month HIV Screening Behavior of Black Men who have Sex with Men in the United States: Results from the POWER Study. AIDS Behav. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison A, Colvin CJ, Kuo C, Swartz A, Lurie M. Sustained High HIV Incidence in Young Women in Southern Africa: Social, Behavioral, and Structural Factors and Emerging Intervention Approaches. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12(2):207–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ostrach B, Merrill S. At special risk: Biopolitical vulnerabilty and HIV/STI syndemics among women. Health Sociology Review. 2012;21(3):258–71. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deuba K, Anderson S, Ekstrom AM, Pandey SR, Shrestha R, Karki DK, et al. Micro-level social and structural factors act synergistically to increase HIV risk among Nepalese female sex workers. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;49:100–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parsons JT, Antebi-Gruszka N, Millar BM, Cain D, Gurung S. Syndemic Conditions, HIV Transmission Risk Behavior, and Transactional Sex Among Transgender Women. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(7):2056–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson LE, Wilton L, Moineddin R, Zhang N, Siddiqi A, Sa T, et al. Economic, Legal, and Social Hardships Associated with HIV Risk among Black Men who have Sex with Men in Six US Cities. J Urban Health. 2016;93(1):170–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, Millett GA. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102 Suppl 2:S242–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. Exploring the relationship between incarceration and HIV among black men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(2):218–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quinn K, Voisin DR, Bouris A, Schneider J. Psychological distress, drug use, sexual risks and medication adherence among young HIV-positive Black men who have sex with men: exposure to community violence matters. AIDS Care. 2016;28(7):866–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reisner SL, Bailey Z, Sevelius J. Racial/ethnic disparities in history of incarceration, experiences of victimization, and associated health indicators among transgender women in the U.S. Women Health. 2014;54(8):750–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The University of New Hampshire. National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NATSCEV I), Final Report. 2014. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice; Available at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/grants/248444.pdf (accessed 6/6/2019). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Operario D, Nemoto T. HIV in transgender communities: syndemic dynamics and a need for multicomponent interventions. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55 Suppl 2:S91–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthews DD, Smith JC, Brown AL, Malebranche DJ. Reconciling Epidemiology and Social Justice in the Public Health Discourse Around the Sexual Networks of Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):808–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Knowlton AR, Wilkinson JD, Gourevitch MN, Knight KR. Syndemic vulnerability, sexual and injection risk behaviors, and HIV continuum of care outcomes in HIV-positive injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):684–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bishaw A Changes in areas with concentrated poverty: 2000 to 2010 American Community Survey Reports. 2014. U.S. Census Bureau; https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2014/acs/acs-27.pdf (accessed 3/12/2019). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carson EA, Anderson E. Prisoners in 2015. 2016. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice; Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p15.pdf (accessed 6/6/2019). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) [online]. (2005) [cited March 9th, 2019]. Available from URL: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars [Internet].

- 46.Morgan RE, Kena G. Criminal Victimization, 2016: Revised. 2017. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice; Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv16re.pdf (accessed 6/6/2019). [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCart MR, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Ruggiero KJ. Do urban adolescents become desensitized to community violence? Data from a national survey. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(3):434–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ojikutu BO, Bogart LM, Klein DJ, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ. Neighborhood Crime and Sexual Transmission Risk Behavior among Black Men Living with HIV. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):383–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Voisin DR, Hotton AL, Schneider JA, Team UCS. The relationship between life stressors and drug and sexual behaviors among a population-based sample of young Black men who have sex with men in Chicago. AIDS Care. 2017;29(5):545–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mena L, Crosby RA, Geter A. A novel measure of poverty and its association with elevated sexual risk behavior among young Black MSM. Int J STD AIDS. 2017;28(6):602–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brewer RA, Magnus M, Kuo I, Wang L, Liu TY, Mayer KH. The high prevalence of incarceration history among Black men who have sex with men in the United States: associations and implications. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):448–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Khan MR, Doherty IA, Schoenbach VJ, Taylor EM, Epperson MW, Adimora AA. Incarceration and high-risk sex partnerships among men in the United States. J Urban Health. 2009;86(4):584–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morgan E, Nyaku AN, D’Aquila RT, Schneider JA. Determinants of HIV Phylogenetic Clustering in Chicago Among Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men From the uConnect Cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;75(3):265–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crosby RA, Salazar LF, Hill B, Mena L. A comparison of HIV-risk behaviors between young black cisgender men who have sex with men and young black transgender women who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2018;29(7):665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Siembida EJ, Eaton LA, Maksut JL, Driffin DD, Baldwin R. A Comparison of HIV-Related Risk Factors Between Black Transgender Women and Black Men Who Have Sex with Men. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):172–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rood BA, Reisner SL, Surace FI, Puckett JA, Maroney MR, Pantalone DW. Expecting Rejection: Understanding the Minority Stress Experiences of Transgender and Gender-Nonconforming Individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):151–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth: Research Evidence and Clinical Implications. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016;63(6):985–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McConnell EA, Janulis P, Phillips G 2nd, Truong R, Birkett M. Multiple Minority Stress and LGBT Community Resilience among Sexual Minority Men. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2018;5(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crawford I, Allison KW, Zamboni BD, Soto T. The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. J Sex Res. 2002;39(3):179–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huebner DM, Kegeles SM, Rebchook GM, Peterson JL, Neilands TB, Johnson WD, et al. Social oppression, psychological vulnerability, and unprotected intercourse among young Black men who have sex with men. Health Psychol. 2014;33(12):1568–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thoma BC, Huebner DM. Health consequences of racist and antigay discrimination for multiple minority adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(4):404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98(2):310–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, Mayer KH. Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: theory and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pitpitan EV, Smith LR, Goodman-Meza D, Torres K, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, et al. “Outness” as a Moderator of the Association Between Syndemic Conditions and HIV Risk-Taking Behavior Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Tijuana, Mexico. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(2):431–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qiao S, Li X, Stanton B. Social support and HIV-related risk behaviors: a systematic review of the global literature. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):419–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arnold EA, Sterrett-Hong E, Jonas A, Pollack LM. Social networks and social support among ball-attending African American men who have sex with men and transgender women are associated with HIV-related outcomes. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(2):144–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hermanstyne KA, Green HD Jr., Cook R, Tieu HV, Dyer TV, Hucks-Ortiz C, et al. Social Network Support and Decreased Risk of Seroconversion in Black MSM: Results of the Brothers (HPTN 061) Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lauby JL, Marks G, Bingham T, Liu KL, Liau A, Stueve A, et al. Having supportive social relationships is associated with reduced risk of unrecognized HIV infection among black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):508–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Scott HM, Pollack L, Rebchook GM, Huebner DM, Peterson J, Kegeles SM. Peer social support is associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):913–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schneider JA, Cornwell B, Ostrow D, Michaels S, Schumm P, Laumann EO, et al. Network mixing and network influences most linked to HIV infection and risk behavior in the HIV epidemic among black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):e28–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Buttram ME, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL. Substance use and sexual risk mediated by social support among Black men. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Voisin DR, Hotton AL, Neilands TB. Testing pathways linking exposure to community violence and sexual behaviors among African American youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2014;43(9):1513–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voisin DR, Neilands TB. Community violence and health risk factors among adolescents on Chicago’s southside: does gender matter? J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(6):600–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Skaathun B, Khanna AS, Morgan E, Friedman SR, Schneider JA. Network Viral Load: A Critical Metric for HIV Elimination. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77(2):167–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McFadden RB, Bouris AM, Voisin DR, Glick NR, Schneider JA. Dynamic social support networks of younger black men who have sex with men with new HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2014;26(10):1275–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2012–2016. 2018; https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ (accessed May 11, 2018).

- 78.Wilkerson I The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration. New York: Vintage Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bechteler SS. 100 Years and counting: the enduring legacy of racial residential segregation in Chicago in the post-civil rights era, Part 1. Chicago, IL: Chicago Urban League; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Derogatis LR, Spencer P. Brief Symptom Inventory: BSI. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Stein MB, Walker JR, Hazen AL, Forde DR. Full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a community survey. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154(8):1114–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Voisin D Victims of Community Violence and HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors Among African American Adolescent Males. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents and Children. 2003;5(3/4):87–110. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsang MA, Schneider JA, Sypsa V, Schumm P, Nikolopoulos GK, Paraskevis D, et al. Network Characteristics of People Who Inject Drugs Within a New HIV Epidemic Following Austerity in Athens, Greece. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(4):499–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reisner SL, Biello K, Rosenberger JG, Austin SB, Haneuse S, Perez-Brumer A, et al. Using a two-step method to measure transgender identity in Latin America/the Caribbean, Portugal, and Spain. Arch Sex Behav. 2014;43(8):1503–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lumley T survey: analysis of complex survey samples. R package version 3.35–1. 2019.

- 86.Gile KJ, Handcock MS. Respondent-Driven Sampling: An Assessment of Current Methodology. Sociol Methodol. 2010;40(1):285–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Livak B, Michaels S, Green K, Nelson C, Westbrook M, Simpson Y, et al. Estimating the number of young Black men who have sex with men (YBMSM) on the south side of Chicago: towards HIV elimination within US urban communities. J Urban Health. 2013;90(6):1205–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Akaike H Likeliood of a model and information criteria. Journal of Econometrics. 1981;16:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.O’Brien RM. A Caution Regarding Rules of Thumb for Variance Inflation Factors. Quality & Quantity. 2007;41:673–90. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Truman JL, Lynn L. Criminal Victimization, 2014. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2015. Available at: https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv14.pdf (accessed 6/19/2019). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Reisner SL. Poverty matters: contextualizing the syndemic condition of psychological factors and newly diagnosed HIV infection in the United States. AIDS. 2014;28(18):2763–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones KT, Johnson WD, Wheeler DP, Gray P, Foust E, Gaiter J, et al. Nonsupportive peer norms and incarceration as HIV risk correlates for young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(1):41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Carlos JA, Bingham TA, Stueve A, Lauby J, Ayala G, Millett GA, et al. The role of peer support on condom use among Black and Latino MSM in three urban areas. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(5):430–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM. Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27(1):415–44. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cohen S Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7(3):269–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cohen S Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bouris A, Hill BJ. Exploring the Mother-Adolescent Relationship as a Promotive Resource for Sexual and Gender Minority Youth. J Soc Issues. 2017;73(3):618–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bouris A, Hill BJ, Fisher K, Erickson G, Schneider JA. Mother-Son Communication About Sex and Routine Human Immunodeficiency Virus Testing Among Younger Men of Color Who Have Sex With Men. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57(5):515–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Garofalo R, Mustanski B, Donenberg G. Parents know and parents matter; is it time to develop family-based HIV prevention programs for young men who have sex with men? J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(2):201–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Hotton AL, Keene L, Corbin DE, Schneider J, Voisin DR. The relationship between Black and gay community involvement and HIV-related risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2018;30(1):64–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chamberlain N, Mena LA, Geter A, Crosby RA. Is Sex with Older Male Partners Associated with Higher Sexual Risk Behavior Among Young Black MSM? AIDS Behav. 2017;21(8):2526–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Joseph HA, Marks G, Belcher L, Millett GA, Stueve A, Bingham TA, et al. Older partner selection, sexual risk behaviour and unrecognised HIV infection among black and Latino men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87(5):442–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bingham TA, Harawa NT, Johnson DF, Secura GM, MacKellar DA, Valleroy LA. The effect of partner characteristics on HIV infection among African American men who have sex with men in the Young Men’s Survey, Los Angeles, 1999–2000. AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15(1 Suppl A):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Latkin C, Yang C, Tobin K, Roebuck G, Spikes P, Patterson J. Social network predictors of disclosure of MSM behavior and HIV-positive serostatus among African American MSM in Baltimore, Maryland. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):535–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Underhill K, Dumont D, Operario D. HIV prevention for adults with criminal justice involvement: a systematic review of HIV risk-reduction interventions in incarceration and community settings. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):e27–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dickson-Gomez J, Owczarzak J, St Lawrence J, Sitzler C, Quinn K, Pearson B, et al. Beyond the ball: implications for HIV risk and prevention among the constructed families of African American men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(11):2156–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chernoff RA, Davison GC. An evaluation of a brief HIV/AIDS prevention intervention for college students using normative feedback and goal setting. AIDS Educ Prev. 2005;17(2):91–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002(14):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Martens MP, Page JC, Mowry ES, Damann KM, Taylor KK, Cimini MD. Differences between actual and perceived student norms: an examination of alcohol use, drug use, and sexual behavior. J Am Coll Health. 2006;54(5):295–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.