Dear Editor,

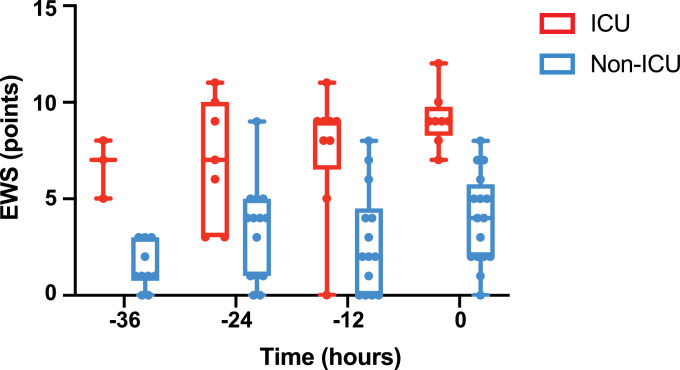

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) that causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) poses multiple challenges to our healthcare systems. A particular challenge is the surge of hospital admissions with a significant fraction requiring transfer to intensive care units (ICU) because of respiratory failure.1 , 2 Early recognition of patients requiring ICU admission is a critical step in the management of COVID-19 patients. We read with interest the communication in this Journal from Su and colleagues who investigated the utility of clinical scoring systems to predict ICU requirement in patients with COVID-19.3 Scoring at admission may however be fraught with heterogeneity due to the timing of presentation. Here, we asked whether a monitoring tool on the wards could help identify patients that would require intensive care up to 36 hours in advance. Early warning scores have been developed as composite scores to quantify patient's deterioration.4 We reviewed data from 36 consecutive PCR-positive COVID-19 patients admitted to the medical wards of the Lausanne University Hospital between March 2, 2020 and March 17, 2020 and examined whether a modified version of the Early Warning Score (EWS) described by Prytherch et al.4 could contribute to an early identification of COVID-19 patients requiring ICU admission. All variables described by Prytherch et al. were included except for the AVPU variable, which is only documented in a subset of departments at our hospital. Physiological variables were analyzed during a 12 to 36-hour period prior to ICU admission (ICU group) or prior to the most abnormal respiratory variables (i.e. FiO2 or respiratory rate) (non-ICU group) defined as t0. EWS was calculated at 12-hour intervals prior t0. Among the 36 patients, 9 were excluded for the following reasons: incomplete or single set of physiological variables (7 patients), pregnancy or immediate ICU admission (1 patient each). Nine required ICU admission and 17 did not. The median age (range) of patients was 74 yr (39-86) in the ICU group and 65.5 yr (26-83) in the non-ICU group (p=0.793). Mean duration of symptoms prior to t0 was 7.8 days in the ICU-group and 7.6 days in the non-ICU group. Risk factors2 associated with severe COVID-19 were present in 80.8% of the patients (ICU group: 77.7% and non-ICU group: 82.3%). Fig. 1 shows the evolution of the EWS over a study period up to 36 hours prior t0 in the two groups of patients. The median EWS was significantly higher in a time-dependent manner in ICU group than in the non-ICU group (p<0.0001) as assessed by mixed effects model5. At t0 or t-12 hours, an EWS greater than 7 predicted ICU admission with sensitivities and specificities of 87% and 93% and 94% and 78%, respectively (AUROC 0.98 and 0.88, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Evolution of the Early Warning Score (EWS) over time in the two groups of patients. EWS was assessed at 12-h intervals over a 36-hour time period. Time zero refers to the time at which the last set of physiological variables was recorded prior to ICU admission (ICU group, red) or to the worst respiratory variables (non-ICU group, blue). Median (range) EWS was 1 (0-3) vs 7 (5-8) (p= 0.25) at -36-h; 4 (0-9) vs 7 (3-11) (p = 0.1875) at -24-h, 2 (0-8) vs 9 (0-11) (p = 0.0078) at –12-h and 9 (7-12) vs 4 (0-8) (p= 0.0078) at -0h (Wilcoxon test). Number of patients per treatment group at each time point (-36h: 3 vs. 11; -24h: 7 vs 12, -12h: 9 vs 15, 0h: 8 vs 17).

These data suggest that EWS may help clinicians identify in advance COVID-19 patients who will require ICU admission. The low number of patients considered and its retrospective and single-center setting limits this study. Still, in time of patient surge, this simple tool may prove useful for initial triage in the emergency department and subsequent monitoring of patients upon admission to hospital wards.

Declarations

- The CER-VD (ref. nbr. 2020-00776) waived consent to participate and consent for publication for this research according to ORH art. 34 (Switzerland).

- No funding was required for this work.

- Authors’ contribution: Study design: SM; Literature search SM, RA; Data collection: SM, PAB, JR, FD, Figure SM, TC, Writing SM, TC, RA.

- Author Information: SM, JR, TC: Infectious Diseases Service, Department of Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. RA Service of Geriatric Medicine and Geriatric Rehabilitation, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland. PAB Department of Medicine, Internal Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland. FD Emergency department, Lausanne University Hospital, Switzerland.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Raphael Burger of the Internal Medicine Department of Lausanne University Hospital, Isabelle Guilleret, Vassili Soumas and Fady Fares at the Clinical Trial Unit of Lausanne University Hospital as well as Patrick Francioli.

References

- 1.Grasselli G., Pesenti A., Cecconi M. Critical Care Utilization for the COVID-19 Outbreak in Lombardy. Jama. 2020;323 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. New Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su Y., Tu G.-W., Ju M.-J. Comparison of CRB-65 and quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment for predicting the need for intensive respiratory or vasopressor support in patients with COVID-19. J Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prytherch D.R., Smith G.B., Schmidt P.E., Featherstone P.I. ViEWS—Towards a national early warning score for detecting adult inpatient deterioration. Resuscitation. 2010;81:932–937. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean R.A., Sanders W.L., Stroup W.W. A Unified Approach to Mixed Linear Models. Am Statistician. 1991;45:54. [Google Scholar]