Abstract

Objective:

To estimate alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drug use during pregnancy among nulliparous women.

Methods:

In a cohort of nulliparous women followed through pregnancy from the first-trimester Nulliparous Outcomes in Pregnancy: Monitoring Mothers to be (nuMoM2b) study, self-reported use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs was chronicled longitudinally at 4 study visits in this secondary analysis. Rates of use before pregnancy, in each trimester (visit 1, visit 2, visit 3, approximating each trimester), and at the time of delivery (visit 4) were recorded. The amount of alcohol, tobacco, and drug exposure were recorded using validated measures, and trends across pregnancy were analyzed.

Results:

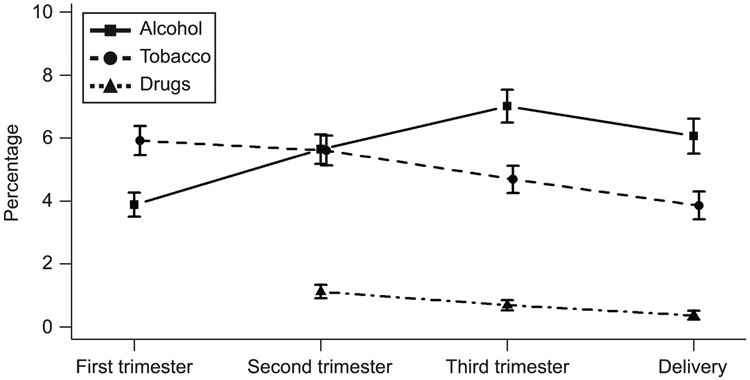

Of the 10,038 study participants, 10,028 had information regarding alcohol, tobacco, and drug use at visit 1, 9,412 at visit 2, 9,217 at visit 3, and 7,167 at visit 4. The rates of drinking alcohol, which had been 64.6% in the 3 months before pregnancy, were lower in pregnancy (3.9% at visit 1, 5.6% at visit 2, 7.0% at visit 3, and 6.1% at visit 4, p<0.001 for all). Rates later in pregnancy were all greater than in the first trimester (p<0.01). The rate of smoking in the 3 months prior to pregnancy, which was 17.8%, also declined at visit 1 (5.9%), and continued to decline through pregnancy (5.3% at visit 2, 4.7% at visit 3, and 3.9% at visit 4, with all rates lower than that of visit 1 (p<0.01)). While recreational drug use was relatively common in the months before pregnancy (33.8%), it also declined during pregnancy (1.1% at visit 2, 0.7% at visit 3, 0.4% at visit 4).

Conclusions:

In this geographically and ethnically diverse cohort of nulliparous women, rates of self-reported alcohol, smoking, and recreational drug use were all significantly lower during than prior to pregnancy. Nonetheless, rates of alcohol use rose as pregnancy progressed, highlighting the need for continued counseling throughout all trimesters of pregnancy.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Precis

The frequency of alcohol use increased as pregnancy progressed in this cohort of nulliparous women.

Introduction

Substance use – including alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs - is relatively common in the United States. As many substances may have ramifications for pregnant women and the developing fetus, pregnant women often will stop using such substances [1] and providers typically will counsel against their use.

Although many studies have reported the prevalence of substance use, the rates have varied widely. For example, over 11% of pregnant women aged 18–44 reported drinking alcohol during pregnancy in the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS, an ongoing national telephone survey of health-related behaviors), with 3.9% reporting binge drinking during the past 30 days while pregnant.[2] Other data have shown that up to 50% of women reported consuming alcohol during pregnancy.[3] Rates of tobacco use during pregnancy have been reported to be 7.2% in 2016, although these rates are thought to be higher among women who are younger, living in an urban setting, and socioeconomically disadvantaged.[4] There has been great variability in reported rates of recreational drugs as well.[5, 6] Some surveys have estimated a prevalence of cocaine use during pregnancy of 4% while others have documented a rate as high as 31%.[7, 8] One reason for such variability in these reported rates is that they have been derived from a wide variety of different populations and from many types of data sources, including birth certificates, cross-sectional interviews, and longitudinal surveys.

Thus, the objective of this study was to ascertain more accurate and generalizable rates of self-reported alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drug use throughout pregnancy for nulliparous women. By using prospectively collected, validated questionnaires at multiple time points during pregnancy beginning in the first trimester, we aimed to improve on prior study limitations through a robust description of substance use in a large sample of pregnant women at multiple sites in the United States.

Methods

This study was a secondary analysis of the Nulliparous Outcomes in Pregnancy: Monitoring Mothers to be (nuMoM2b) cohort study. The detailed methods of the nuMoM2b study are described elsewhere.[9] Briefly, 10,038 nulliparous women were recruited in the first trimester of pregnancy between October 2010 and September 2013 at eight geographically diverse study sites throughout the United States. These sites were in California, Utah, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Delaware. Women had study visits from gestational weeks 6+0/7 to 13+6/7 (visit 1), 16+0/7 to 21+6/7 (visit 2), 22+0/7 to29+6/7 (visit 3), and during the delivery hospitalization (visit 4). Study visits were conducted separately from routine clinical care. At each study visit, a trained research team member administered several questionnaires and surveys and collected an array of biological samples. All women gave written informed consent and the local governing institutional review boards of each study center approved the study.

At visit 1, women were asked a series of validated questions about substance use adapted from the BRFSS,[2] including whether they had used substances in the 3 months prior to becoming pregnant and the 30 days prior to the study visit. The 30 days prior to visit 1 responses were utilized to approximate use in the first trimester. At visit 2, visit 3, and visit 4, women were asked the same questions about use of the substances in the 30 days prior to the study visit.

Alcohol use was captured by asking about what type of alcohol product was consumed and in what quantities. Binge drinking was defined as drinking at least 4 drinks during a single occasion.[2] Tobacco use was quantified by asking about use of cigarettes, cigars, other smoked products, or smokeless tobacco. Nicotine patches, gums, and similar products were also documented. There were no questions about electronic cigarettes (i.e., vaping) as this form of smoking was not commonplace when the study was designed. Recreational drugs that were specifically asked about at each visit included heroin, cocaine, marijuana (THC), hallucinogens, prescription opioids that had not been prescribed to the participant, and other recreational drugs. Due to a form design error, drug use in the month prior to the visit was not asked at visit 1. All interviews and data collected were confidential and a Certificate of Confidentiality was in place for all study sites.

Women were included in this analysis if they had completed questions for at least one of the epochs. Rates of use were reported for each epoch of pregnancy. For categorical variables, the frequency of use and 95% confidence interval (CI) – derived using binomial proportions - were estimated. For continuous variables, the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum, and maximum were determined.

Generalized linear mixed models were employed to examine the probability of using alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs separately. Based on the models, the frequency was compared between visit 1 and each subsequent study visit. Multiple comparisons were adjusted for by the Sidak method.

Results

Of the 10,038 women in the nuMoM2b study, 10,028 (99.9%) provided valid answers to the questions regarding substance use at visit 1, 9,412 (93.7%) at visit 2, 9.217 (91.8%) at visit 3, and 7,167 (71.4%) at visit 4. The non-responses at each visit were either due to participants not completing the visit interview, delivering before visit 3 or at a facility without study personnel, or failing to answer one of the component questions. Most women had complete answers for the primary use questions at all 4 time points (n=6,687 (66.7%)). The characteristics of the overall cohort are described elsewhere.[9] Briefly, the population had a mean maternal age of 26.9 (±5.7) years and was comprised of women who self-identified as non-Hispanic white (59.7%), non-Hispanic black (14.2%), Hispanic (16.9%), Asian (4.0%), or other (5.1%, Table 1). Demographic characteristics between women with complete data for all four visits and those without complete data were not meaningfully different, excepting a higher rate of Hispanics in the non-complete group (24.9% vs. 13.0%, p<0.001, Table 2).

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of the nuMoM2b cohort

| Characteristic (N=10,038) | Value |

|---|---|

| Maternal age- in years | |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 26.9 ±5.7 |

| Category: n (%) | |

| 13-21 | 2128 (21.2) |

| 22-35 | 7228 (72.1) |

| >35 | 670 (6.7) |

| Gravidity: n (%) | |

| 1 | 7437 (74.2) |

| 2 | 1913 (19.1) |

| 3+ | 676 (6.7) |

| Maternal race/ethnicity: n (%) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 5988 (59.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1420 (14.2) |

| Hispanic | 1699 (16.9) |

| Asian | 406 (4.0) |

| Other | 514 (5.1) |

| Education status attained: n (%) | |

| less than high school | 815 (8.1) |

| completed high school or GED | 1170 (11.7) |

| some college | 1947 (19.4) |

| associate or technical degree | 1005 (10.0) |

| completed college | 2772 (27.7) |

| degree work beyond college | 2308 (23.0) |

| Method of paying for healthcare: n (%)* | |

| government insurance | 2854 (28.7) |

| military insurance | 65 (0.7) |

| commercial health insurance | 6776 (68.1) |

| personal household income | 1720 (17.3) |

| other | 132 (1.3) |

| Income and size of household relative to Federal poverty level: n (%) | |

| >200% | 5662 (69.7) |

| 100-200% | 1171 (14.4) |

| <100% | 1296 (15.9) |

Percentages do not add up to 100% as participants were allowed to select multiple methods.

Table 2:

Comparison of demographic characteristics for women who had complete answers for the primary questions at all four study visits and those who did not have complete responses

| Completer (N = 6687) |

Non-completer (N = 3341) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 27.1 (5.5) | 26.7 (6.0) | 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 4348 (65.0%) | 1641 (49.1%) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 853 (12.8%) | 565 (16.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 869 (13.0%) | 831 (24.9%) | |

| Asian | 273 (4.1%) | 134 (4.0%) | |

| Other | 344 (5.1%) | 170 (5.1%) | <0.001 |

| Education | |||

| Less than HS graduate | 474 (7.1%) | 342 (10.3%) | |

| HS or GED graduate | 736 (11.0%) | 435 (13.1%) | |

| Some college | 1244 (18.6%) | 704 (21.1%) | |

| Associate/Technical degree | 703 (10.5%) | 302 (9.1%) | |

| Completed college | 1954 (29.2%) | 818 (24.5%) | |

| Degree work beyond college | 1575 (23.6%) | 733 (22.0%) | <0.001 |

We calculated the response rate based on the maximum sample size across three items presented in table 1 (“Drink alcoholic beverages”, “Smoke any tobacco product”, and “Use any illegal drug or drug not prescribed for them”). Data are presented as n (%) unless otherwise specified.

HS= high school; GED= general educational development

The majority of women in the nuMoM2b cohort reported ever consuming alcohol (n=8,612 (86.0%), Table 3). Of women who had ever consumed alcohol, 6,477 (75.2%) of them had consumed alcohol in the 3 months prior to getting pregnant (this represented 64.6% of the entire cohort) with a median frequency of 1 day per week (standard deviation= 1.42, range 0–7, Table 4). Of participants who reported drinking alcohol in the 3 months prior to pregnancy, 53.1% reported enough drinking to qualify as binge drinking. During the first trimester, 381 (3.9%, Table 3, Figure) of women reported drinking alcoholic beverages, with 8.7% of them drinking more than 1 day per week. Of the women who reported drinking during pregnancy, 35 (9.2%) met criteria for binge drinking at least once during the first trimester. We did not ask about rate of binge drinking before participants knew they were pregnant.

Table 3:

Responses of nulliparous women reporting use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs during pregnancy

| Characteristic | In the 3 months before pregnancy began |

In the month before visit 1 (first trimester exposure) |

In the month before visit 2 (second trimester exposure) |

In the month before visit 3 (late second/early third trimester exposure) |

In the month before the delivery visit (exposure around the time of delivery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | |||||

| Drink alcoholic beverages | 6477/10028 | 381/9824 | 531/9409 | 646/9217 | 434/7164 |

| 64.6% (63.6%-65.5%) | 3.9% (3.5%-4.3%) | 5.6% (5.2%-6.1%)† | 7.0% (6.5%-7.6%)† | 6.1% (5.5%-6.6%)† | |

| Drink > 1 day per week | 2740/6459 | 33/378 | 14/528 | 45/641 | 48/431 |

| 42.4% (41.2%-43.6%) | 8.7% (6.1%-12.0%) | 2.7% (1.5%-4.4%) | 7.0% (5.2%-9.3%) | 11.1% (8.3%-14.5%) | |

| Binge drinking | 3414/6429 | 33/375 | 16/522 | 23/638 | 13/428 |

| 53.1% (51.9%-54.3%) | 8.8% (6.1%-12.1%) | 3.1% (1.8%-4.9%) | 3.6% (2.3%-5.4%) | 3.0% (1.6%-5.1%) | |

| Tobacco | |||||

| Smoke any tobacco products | 1782/10028 | 592/10015 | 499/9407 | 432/9217 | 276/7162 |

| 17.8% (17.0%-18.5%) | 5.9% (5.5%-6.4%) | 5.3% (4.9%-5.8%)† | 4.7% (4.3%-5.1%)† | 3.9% (3.4%-4.3%)† | |

| Smoked >1 pack per day | 257/1771 | 14/588 | 15/497 | 13/429 | 9/274 |

| 14.5% (12.9%-16.2%) | 2.4% (1.3%-4.0%) | 3.0% (1.7%-4.9%) | 3.0% (1.6%-5.1%) | 3.3% (1.5%-6.1%) | |

| Exposed to second hand smoke | 1901/5548 | 1452/5543 | 1377/5749 | 1263/6207 | 704/5308 |

| 34.3% (33.0%-35.5%) | 26.2% (25.0%-27.4%) | 24.0% (22.9%-25.1%) | 20.4% (19.4%-21.4%) | 13.3% (12.4%-14.2%) | |

| Smoked ≥ 7 hours per week who exposed to second hand smoke | 766/1901 | 512/1452 | 403/1377 | 397/1263 | 230/704 |

| 40.3% (38.1%-42.5%) | 35.3% (32.8%-37.8%) | 29.3% (26.9%-31.8%) | 31.4% (28.9%-34.1%) | 23.7% (29.2%-36.3%) | |

| At least 1 person (excluding subject) who smoked in the home | 855/5556 | 719/5553 | 683/5760 | 640/6210 | 373/5310 |

| 15.4% (14.5%-16.4%) | 13.0% (12.1%-13.9%) | 11.9% (11.0%-12.7%) | 10.3% (9.6%-11.1%) | 7.0% (6.4%-7.8%) | |

| Drugs | |||||

| Use any illegal drug or drug not prescribed for them | 3425/10027* | N/A | 105/9407 | 63/9216 | 26/7163 |

| 34.2% (33.2%-35.1%) | N/A | 1.1 (0.9%-1.4%) | 0.7% (0.5%-0.9%)‡ | 0.4% (0.2%-0.5%)‡ | |

| Use opioid (narcotics- heroin- methadone) | 632/3425 | N/A | 5/105 | 2/63 | 5/26 |

| 18.5% (17.2%-19.8%) | N/A | 4.8% (1.6%-10.8%) | 3.2% (0.4%-11.0%) | 19.2% (6.6%-39.4%) |

Have you EVER used illegal drugs or drugs not prescribed for you?

Compared to the first trimester- all p-values were < 0.001.

Compared to the second trimester- all p-values were < 0.001

Data are reported as n/N and % (95%CI) responding yes.

N/A= not asked at the visit

Table 4.

Responses about additional degree of use and exposure of nulliparous women reporting use of alcohol, tobacco, and drugs during pregnancy

| Characteristic | In the 3 months before pregnancy began |

In the month before visit 1 (first trimester exposure) |

In the month before visit 2 (second trimester exposure) |

In the month before visit 3 (late second/early third trimester exposure) |

In the month before the delivery visit (exposure around the time of delivery) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | |||||

| How many days per week did you drink? - days/week | 6459 | 378 | 528 | 641 | 431 |

| 1.7 ±1.4/ 1 (0- 7) | 0.8 ±0.8/ 1 (0- 5) | 0.6 ±0.6/ 1 (0- 3) | 0.7 ±0.6/ 1 (0- 3) | 0.8 ±0.7/ 1 (0- 5) | |

| How many drinks did you drink per drinking day? - drinks | 6460 | 378 | 528 | 637 | 430 |

| 2.4 ±1.7/ 2 (0- 50) | 1.5 ±2.8/ 1 (0- 50) | 1.0 ±0.3/ 1 (0- 3) | 1.0 ±0.4/ 1 (0- 6) | 1.0 ±0.3/ 1 (0- 3) | |

| How many times did you drink four or more drinks during a single occasion? - times | 6429 | 378 | 528 | 638 | 428 |

| 2.8 ±6.8/ 1 (0- 99) | 0.3 ±2.1/ 0 (0- 30) | 0.04 ±0.3/ 0 (0- 4) | 0.1 ±0.3/ 0 (0- 4) | 0.04 ±0.2/ 0 (0- 3) | |

| Tobacco | |||||

| How many cigarettes did you smoke per day? - # per day | 1771 | 589 | 497 | 429 | 274 |

| 7.8 ±8.7/ 5 (0- 200) | 4.6 ±4.4/ 3 (0- 40) | 5.1 ±4.4/ 4 (0- 25) | 5.4 ±4.9/ 4 (0- 50) | 6.0 ±6.4/ 5 (0- 70) | |

| On average how many hours per week were you exposed to cigarette smoke because of smoking by others? - hours/week | 5548 | 5543 | 5749 | 6207 | 5308 |

| 5.5 ±18.6/ 0 (0- 168) | 3.8 ±15.8/ 0 (0- 168) | 2.6 ±12.1/ 0 (0- 168) | 2.5 ±12.0/ 0 (0- 168) | 1.5 ±9.2/ 0 (0- 168) | |

| How many people (excluding yourself) smoked cigarettes inside the home where you lived? - people | 5556 | 5553 | 5760 | 6210 | 6310 |

| 0.3 ±0.7/ 0 (0- 10) | 0.2 ±0.6/ 0 (0- 7) | 0.2 ±0.6/ 0 (0- 10) | 0.2 ±0.6/ 0 (0- 8) | 0.1 ±0.5/ 0 (0- 6) |

All data are presented as N on the first line and mean ±SD/ median (min- max) on the lower line

At visit 2, 531 women reported drinking alcohol in the month prior to their visit (5.6%), with 14 (2.6%) reporting typically drinking more than 1 day per week. Sixteen women (3.0%) met criteria for binge drinking in the second trimester. At visit 3, 646 (7.0%) of women reported drinking alcohol in the month prior to the study visit. Of those women, 45 (6.9%) reported drinking more than 1 day per week and 23 (3.6%) met criteria for binge drinking. At the delivery interview, 434 women (6.1%) reported drinking alcohol in the month before delivery. Of those women, 48 (11.0%) reported drinking more than 1 day per week. Of those who reported drinking alcohol in the month before delivery, 13 (3.0%) met the criteria for binge drinking. Rates of alcohol consumption at visit 2, visit 3, and delivery were significantly higher than that reported at visit 1 (p<0.001 for all comparisons).

Less than half of the women, 4,187 (41.8%), had ever used any tobacco products, including cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, during their lifetimes. For the entire cohort, the rate of smoking in the 3 months before pregnancy was 17.8% (Table 3). Of women who had ever smoked, 1,782 (42.6%) smoked in the 3 months prior to the pregnancy. In the 3 months prior to pregnancy, 78 women (1.9%) reported using smokeless tobacco. Over one-third of women noted exposure to second hand smoke in the 3 months prior to pregnancy (34.3%), of whom 40.3% claimed at least 7 hours of exposure per week (Table 4).

Five-hundred and ninety-two participants acknowledged smoking tobacco products in the first trimester (5.9%) (Table 3). Additionally, 1,452 (22.6%) reported exposure to second hand smoke during the first trimester, with 427 (29.4%) exposed to ≥7 hours of second hand smoke per week (Table 4). Only 59 women (1.4%) reported using nicotine gum, patch, spray, or inhaler during the first trimester. Additionally, 12 women (0.3%) used smokeless tobacco in the first trimester. Six women (0.1%) took bupropion to help them stop smoking during the first trimester.

During the second trimester, 499 women (5.3%) reported smoking (Table 3). Second hand smoke exposure was endorsed by 24.0% of women at visit 2, but only 29.3% reported exposure to ≥7 hours per week. At visit 2, 44 women (0.5%) endorsed using nicotine gum, patch, spray, or inhaler, 7 (0.07%) claimed to have used bupropion for smoking cessation, and 6 (0.06%) claimed to use smokeless tobacco.

During visit 3, 432 women (4.7%) reported smoking in the month prior to the visit (Table 3). Second hand smoke exposure was endorsed by 20.3% of women at visit 3, of whom 31.4% reported exposure to ≥7 hours per week. Only 10.3% of participants stated they had at least 1 additional smoker in the house. At visit 3, 29 women (0.3%) endorsed using nicotine gum, patch, spray, or inhaler, 4 (0.04%) claimed to have used bupropion for smoking cessation, and 6 (0.07%) claimed to use smokeless tobacco.

At visit 4, 276 women (3.9%) stated that they had smoked in the month prior to delivery (Table 3). Compared to smoking rates in the first trimester, smoking rates at visit 2, visit 3, and visit 4 were lower (p<0.001 for each comparison, Table 3).

When asked if they had ever used recreational drugs or drugs not prescribed for them, 3,425 (34.2%) stated that they had (Table 3). A total of 3,388 women (33.8%) used drugs during the 3 months prior to pregnancy. The most common drug used by participants in the 3 months before pregnancy was marijuana (THC, n=3340 (33.3%)), followed by cocaine (n= 625, 6.2%), hallucinogens (n=616, 6.1%), prescription narcotics not prescribed for them (n=600, 6.0%), amphetamines (n=226, 2.2%), inhalants, (n=103, 1.0%), heroin (n=97, 1.0%), methadone (n=63, 0.6%), and “other” drugs (n=238, 2.4%). A total of 632 women (6.3%) had ever used any opioid not prescribed to them. Of the women reporting recreational drug use before pregnancy, only 256 women (7.5%) stated that they had ever felt they had a problem with their use of these drugs and only 244 (7.2%) considered themselves to be addicted. As noted in the methods, women were not asked at visit 1 about drug use in the last month prior to the study visit.

At visit 2, 105 women (1.1%) endorsed using recreational drugs or drugs not prescribed to them in the month before the visit (Table 3). The majority of these reported marijuana (n=101, 96.2%) with two women each endorsing use of heroin, prescription narcotics, “other” drugs, and only one woman reporting methadone. Five women self-reported using any opioid during the second trimester (0.05% of the entire cohort, 4.8% of women reporting recreational drug use).

At visit 3, 63 women (0.7%) endorsed using drugs in the month prior (Table 3). Again, the majority used marijuana (n=60, 95.2%). Two women in the cohort endorsed taking opioids during this late second-early third trimester period (0.02% of entire cohort, 3.2% of women reporting recreational drug use).

At visit 4, only 26 women (0.4%) endorsed using drugs (Table 3). Nineteen of these women endorsed using THC (73.1%). Five women self-reported using an opioid in the month before delivery (0.07% of entire cohort, 19.2% of those reporting recreational drug use).

Discussion

A large proportion of nulliparous women enrolled in this large prospective cohort study reported ever using alcohol (86.0%), tobacco (41.8%), and recreational drugs (34.2%). However, the self-reported rates for use of these substances during pregnancy were much lower.

Alcohol use was self-reported in the 3 months before pregnancy by over 64% of the women. This is somewhat higher than other reported rates such as the 50% noted by the 2004 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS).[3] Conversely, the rate of alcohol use during pregnancy in the nuMoM2b study were lower (up to 7%) than the 30% reported in the 2009 National Birth Defects Prevention Study of over 4,000 women.[10] Our reported rate of use was also lower than the data from the BRFSS from which our questions were adapted. This lower rate may be due to not capturing all use as our survey only asked about use in the one month prior to the study visit. Thus, it might have missed use very early in pregnancy before the woman knew she was pregnant. The BRFSS data from 2011–2013, a time when the nuMoM2b cohort was being recruited, noted a 10.2% rate of drinking in the past 30 days among pregnant women.[11] Alcohol use in pregnancy is associated with older age groups, black race, and educated women.[11] The nuMoM2b cohort included younger women than the other previous surveys; 20% were between the ages of 13–21.[9] Additionally, alcohol use in our cohort increased as the pregnancy progressed. As there is no “safe” amount of alcohol to be consumed in pregnancy[12], this is concerning. It is possible that women are more worried about birth defects early in the pregnancy and feel that as pregnancy progresses, it becomes “safer” to drink as they have already had ultrasounds showing no anatomical problems with the developing baby. This should be studied further. While the majority of women in our cohort did not drink frequently, the finding that nearly 10% of the women met criteria for binge drinking in the first trimester was unexpected. This rate decreased in the later parts of pregnancy, becoming more in line with the BRFSS data showing a rate of 3.1% for binge drinking.[10] This is still above the Healthy People 2020 goals of a national rate of abstinence from alcohol in pregnancy of 98.3%.[13]

Tobacco use before pregnancy was reported by nearly 18% of women. This is slightly lower than the 23% rate reported by PRAMS in 2008.[3] However, this rate dropped during pregnancy in our study. The National Vital Statistics Report of births from 2016 reported that 7.2% of women who gave birth smoked during pregnancy[4], which is slightly higher than our population. This may have been because the nuMoM2b cohort did not contain sites in the South, a region with somewhat higher smoking rates among adults.[14] Smoking rates during pregnancy have been decreasing in general.[15] It is possible that our rates are lower due to the nuMoM2b cohort including only nulliparous women, who may be more likely to stop smoking during pregnancy than multiparous women.[16] This also supports our finding of smoking rates decreasing as pregnancy progressed. We also found a high rate of exposure to second-hand smoke during pregnancy. Given that second hand smoke exposure during pregnancy has been associated with adverse outcomes such as small for gestational age growth and childhood diseases such as asthma [17–19], further study into these women and their pregnancy outcomes should be performed.

Although the ever use of recreational drugs was seen in one-third of women before they became pregnant, this rate was much lower during pregnancy. One limitation of this estimate was that even with the Certificate of Confidentiality, women may have been hesitant to disclose their drug use as the question asked if they had taken any “illegal drugs or drugs not prescribed to you”.[20] The majority of drug use was with marijuana (THC), which was legal in the state of only one of the smaller clinical centers for the nuMoM2b study. Prior studies have estimated the self-reported prevalence of marijuana use in pregnancy to be between 2–5%.[5] Given increasing use among young, urban, and socioeconomically disadvantaged women, as well as increasing legalization, it is possible that repeating the survey now in our cohort may yield higher prevalence rates.[5, 21] It has been noted that up to 60% of marijuana smokers continue to use during pregnancy.[22] As 3,340 women claimed to have ever used marijuana in the past and only 60 admitted using it by visit 3, our reported rates of continuation were much lower. Cocaine was the second most commonly reported drug used in our cohort. National self-reported rates of use around 4% during pregnancy have been estimated.[8, 23] Nevertheless, one cross-sectional study around delivery in Detroit found evidence of cocaine use in infants’ meconium in 31% of women, but only 11% admitted to recent cocaine use.[7] As we relied upon self-report for drug use, this is a limitation of our study, particularly given that over half of pregnant women using marijuana may not self-report.[21] Our reported rate of illegal opioid use was low. Women in the nuMoM2b cohort had a prescribed opioid use rate during pregnancy of 3.6%.[24] The low rate of self-reported illegal opioids may have been due to the strict inclusion criteria for the study and possibly due to the geographic locations of the cohort.[9] During pregnancy, the overall rate of drug use in our cohort was low and decreased as pregnancy progressed.

As a large cohort recruited in the first trimester and prospectively followed, with the use of validated questions about alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drug use during the pregnancy, our study overcomes some of the limitations of prior cross-sectional or retrospective surveys. The use of a Certificate of Confidentiality, giving participants reassurance that there would not be reporting of the use of substances during pregnancy to authorities, also may have made women more comfortable to disclose use during the nuMoM2b study visits.

Our study also has limitations. Drug use during the first trimester was not asked during the study visits due to an omission on the data collection form. Also, even when questions were asked, responses were not available for all women due to non-response. There were many women who did not have complete responses at the delivery visit (visit 4). This may have been due to delivery at a facility without study personnel available. This may have contributed to the higher rate of Hispanic women without complete responses. However, the large number of women who had valid responses overcomes some of the difficulties that missing data creates for smaller cohorts. Due to the low rate of use of many of the substances evaluated in this study, we report them descriptively and were not able to perform multivariable predictive models to find maternal characteristics associated with use of these substances. However, the use of these substances can be utilized in other association studies as potential mediators of other exposures and has been included in other nuMoM2b analyses.[25, 26] Lack of a study site in the South may also have impacted rates of other substances used in addition to tobacco. Recruitment of women in the first trimester may have also biased the sample away from women using substances.

In conclusion, nulliparous women in the large nuMoM2b cohort had low, but increasing rates of self-reported alcohol use during pregnancy and low, but decreasing rates of self-reported smoking as pregnancy progressed. These data suggest that there may be benefit to continued patient counseling in all trimesters regarding the possible effects of alcohol use in pregnancy as there is no “safe” amount of alcohol use in pregnancy. The use of recreational drugs was low and was mostly comprised of marijuana use.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Rates of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use throughout pregnancy. All rates from a question asking about use in the month before the respective study visit were: first-trimester exposure from study visit 1 between 6 0/7 and 13 6/7 weeks of gestation; second-trimester exposure from visit 2 between 16 0/7 and 21 6/7 weeks of gestation; and third-trimester exposure from visit 3 between 22 0/7 and 29 6/7 weeks of gestation. Delivery exposure from question asked at the delivery hospitalization. Figure shows point estimates of incidence and 95% CI error bars.

Support acknowledgement:

This study is supported by grant funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD): U10 HD063036, RTI International; U10 HD063072, Case Western Reserve University; U10 HD063047, Columbia University; U10 HD063037, Indiana University; U10 HD063041, University of Pittsburgh; U10 HD063020, Northwestern University; U10 HD063046, University of California Irvine; U10 HD063048, University of Pennsylvania; and U10 HD063053, University of Utah. In addition, support was provided by respective Clinical and Translational Science Institutes to Indiana University (UL1TR001108) and University of California Irvine (UL1TR000153).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Brian M. Mercer disclosed that money was paid to his institution for presentations at national meetings and grand rounds. The other authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Forray A, Merry B, Lin H, Ruger JP, Yonkers KA. Perinatal substance use: a prospective evaluation of abstinence and relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015. May 1;150:147–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denny CH, Acero CS, Naimi TS, Kim SY. Consumption of Alcohol Beverages and Binge Drinking Among Pregnant Women Aged 18–44 Years - United States, 2015–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019. April 26;68(16):365–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Angelo D, Williams L, Morrow B, Cox S, Harris N, Harrison L, et al. Preconception and interconception health status of women who recently gave birth to a live-born infant--Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 26 reporting areas, 2004. MMWR Surveill Summ 2007. December 14;56(10):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman M, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: final data for 2016. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2018. 1/31/2018;67(1):1–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Committee Opinion No. 722: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017;130(4):e205–e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smid MC, Metz TD, Gordon AJ. Stimulant Use in Pregnancy: An Under-recognized Epidemic Among Pregnant Women. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019. March;62(1):168–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrea EM Jr., Brady M, Gause S, Raymundo AL, Stevens M. Drug screening of newborns by meconium analysis: a large-scale, prospective, epidemiologic study. Pediatrics 1992. January;89(1):107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quality CfBHSa. 2015 National survey on drug use and health: detailed tables. Retrieved from http://wwwsamhsagov 2016.

- 9.Haas DM, Parker CB, Wing DA, Parry S, Grobman WA, Mercer BM, et al. A description of the methods of the Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study: monitoring mothers-to-be (nuMoM2b). American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2015;212(4):539.e1–.e24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kitsantas P, Gaffney KF, Wu H, Kastello JC. Determinants of alcohol cessation, reduction and no reduction during pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014. April;289(4):771–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, Sniezek JE, Kanny D. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015. September 25;64(37):1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Tobacco, Alcohol, Drugs, and Pregnancy FAQ 170, February 2019. Frequently Asked Questions 2019. [cited 2019 May 7]; Available from: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Tobacco-Alcohol-Drugs-and-Pregnancy#amount

- 13.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2020. Washington, DC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang TW, Asman K, Gentzke AS, Cullen KA, Holder-Hayes E, Reyes-Guzman C, et al. Tobacco Product Use Among Adults - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018. November 9;67(44):1225–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Committee Opinion No. 721 Summary: Smoking Cessation During Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2017;130(4):929–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cnattingius S, Lindmark G, Meirik O. Who continues to smoke while pregnant? J Epidemiol Community Health 1992. June;46(3):218–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking during pregnancy. [cited 2019 May 6]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/pregnancy/index.htm

- 18.Norsa’adah B, Salinah O. The Effect of Second-Hand Smoke Exposure during Pregnancy on the Newborn Weight in Malaysia. The Malaysian journal of medical sciences : MJMS 2014;21(2):44–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humphrey A, Dinakar C. Maternal Second-Hand Smoke Exposure in Pregnancy Is Associated With Childhood Asthma Development. Pediatrics 2014;134(Supplement 3):S145–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. Journal of general internal medicine 2002;17(5):327–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young-Wolff KC, Tucker L-Y, Alexeeff S, Armstrong MA, Conway A, Weisner C, et al. Trends in Self-reported and Biochemically Tested Marijuana Use Among Pregnant Females in California From 2009–2016. JAMA 2017;318(24):2490–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mark K, Gryczynski J, Axenfeld E, Schwartz RP, Terplan M. Pregnant Women’s Current and Intended Cannabis Use in Relation to Their Views Toward Legalization and Knowledge of Potential Harm. J Addict Med 2017. May/Jun;11(3):211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bhuvaneswar CG, Chang G, Epstein LA, Stern TA. Cocaine and opioid use during pregnancy: prevalence and management. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2008;10(1):59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas DM, Marsh DJ, Dang DT, Parker CB, Wing DA, Simhan HN, et al. Prescription and Other Medication Use in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2018. May;131(5):789–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller ES, Silver RM, Simhan HN, Haas DM, Wing DA, Mercer BM, et al. Can demographic characteristics identify women with self-harm ideation during pregnancy? American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 2019;220(1):S552–S3. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Facco FL, Parker CB, Reddy UM, Silver RM, Koch MA, Louis JM, et al. Association Between Sleep-Disordered Breathing and Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2017. January;129(1):31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.