Congenital defects in the platelet GPIb-IX-V complex which result in quantitative deficiencies cause the Bernard-Soulier syndrome (BSS) bleeding disorder (Nurden and Nurden 2011). BSS is an autosomal recessive disease characterized by moderate to severe thrombocytopenia, giant platelets and mucocutaneous bleeding (Lanza 2006).

Mutations in any one of the three genes GP1BA, GP1BB or GP9 may lead to impaired expression of the GPIb-IX-V complex. The prevalence of BSS has been estimated at less than one in a million live births, but higher frequencies have been observed in particular regions.

The island of Reunion is a French overseas territory where isolation from mainland resulted in founder effects observed for different inherited diseases (Richard, et al 1995, Rodius, et al 1994). Occurrence of BSS has been known for several years in a number of patients referring to the main hospitals of Reunion island. Then, these patients were analyzed for genetic defects in the GP1BA, GP1BB, and GP9 genes. Sequencing of the GP1BB coding region revealed a similar homozygous c.265A>G transition in the 13 affected individuals. This mutation predicts a p.Asn89Asp amino acid change in GPIbβ. Analysis of 7 relatives from 5 families showed that they were all heterozygous for the same mutation (Supplemental Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table I).

The Asn to Asp change falls within the C-terminal region flanking the single LRR motif of GPIbβ. Alignment of corresponding sequences from other species revealed that the Asn mutated in the patient is highly conserved (Supplemental Fig. 2A). As shown in the 3D-model, the side chain of the Asn forms 6 close-knit hydrogen bonds with polar backbone atoms (Supplemental Fig. 2B) (McEwan, et al 2011). The mutation will replace the carboxamide group with a carboxylate, and although the change is relatively small, it will likely perturb the intricate hydrogen bond network around this residue. Therefore, the mutation is expected to be quite destabilizing. In 2003, Strassel et al. reported a homozygous p.Asn89Thr substitution in a BSS patient and showed that this single amino acid substitution in the extracellular domain of GPIbβ affects the expression of both GPIbα and GPIX in transfected CHO cell lines (Strassel, et al 2003). As illustrated in WB analysis of one patient (BSS1), GPIbα, GPIbβ and GPIX subunits, which are probably not correctly associated, were easily degraded leaving only trace amounts or absence of them in platelet lysates (Supp. Fig. 3).

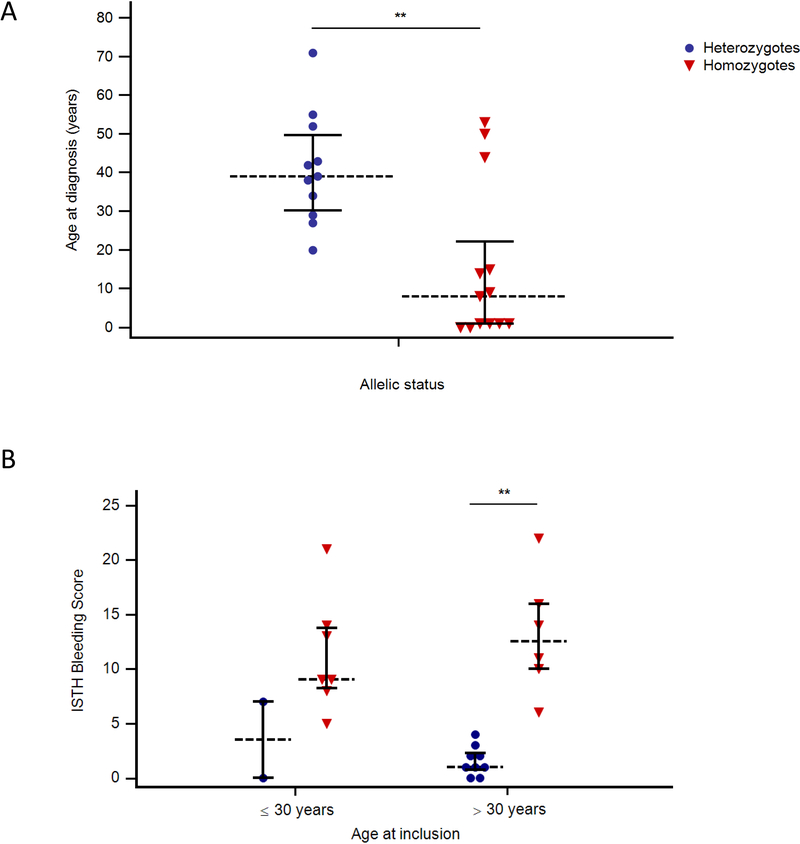

Characteristics of the population study is described in Supplemental Table I. In total, 13 homozygous patients and 11 heterozygous carriers were included. In the group of BSS patients, median age at diagnosis was 8 years (range 0–53 years) and seven patients (54%) had a late diagnosis after the age of 7 (Fig. 1A). In thrombocytopenic heterozygous patients (6/11), the diagnosis of inherited thrombocytopenia was realized at a very late stage (median +/− SD = 42.5 +/− 13 y). Among reasons for diagnostic delay, patients with inherited thrombocytopenia may be mistaken for or misdiagnosed as immune thrombocytopenia (ITP). Indeed, 38% of BSS patients were misdiagnosed as ITP and received treatment for this reason. Furthermore, three patients were splenectomized without receiving any benefit. The study of Savoia et al. also showed that 4 out of 13 BSS patients (31%) had an erroneous diagnosis of autoimmune thrombocytopenia, treated with intravenous immunoglobulins, steroids and/or splenectomy (Savoia, et al 2011). Among heterozygous carrier, at least one patient was misdiagnosed as ITP, but did not receive any treatment.

Figure 1. Clinical characteristics of the population study according to allelic status.

(A) Age at diagnosis; (B) ISTH Bleeding Scores according to age at inclusion.Horizontal bars represent medians and interquartiles. ** p< .01.

Detailed bleeding history for each patient is also reported in Supplemental Table 1. Bleeding diathesis was variable and severity ranged from 5 to 22 (median +/− SD = 11 +/− 4.6) in BSS patients according to the ISTH-BAT (Fig. 1B). All menstruated women (5/8 patients) had menorrhagia that required, in 60% of them, estroprogestinic treatment associated or not with antifibrinolytics. One spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage was reported at the age of 9 months (BSS10). Nine patients (75%) received platelet transfusions to arrest bleeding episodes or in preparation to surgery. Recombinant activated factor VII was administered twice in one patient following head trauma and gingivorrhagia. It is interesting to note that thrombopoietin analog was used off-label, as a therapeutic alternative, in one patient (BSS11) for which we observed a significant improvement of daily rectorrhagia with complete disappearance of bleeding. Finally, while patients from Reunion island bear the same mutation in GPIbβ, our results demonstrated that there was some heterogeneity in the severity of bleeding history.

Reasons for the varying clinical phenotype despite a single homozygous mutation could be explained by the existence of others relevant haemostatic traits, such as von Willebrand factor, or by the personal history of each patient (trauma-related bleedings).

ISTH-BAT of heterozygous carriers ranged from 0 to 7 (median +/− SD = 1.0 +/− 2.1) (Fig. 1B). Only one patient had abnormal bleeding scores associated to diverse bleeding symptoms. None of the heterozygous patients received hemostatic treatment. Similar results were found in the study of Savoia et al. where 7 heterozygous carriers were asymptomatic (Savoia, et al 2011), whereas the study of Bragadottir et al. reported statistically significant bleeding in the heterozygous group (Bragadottir, et al 2015).

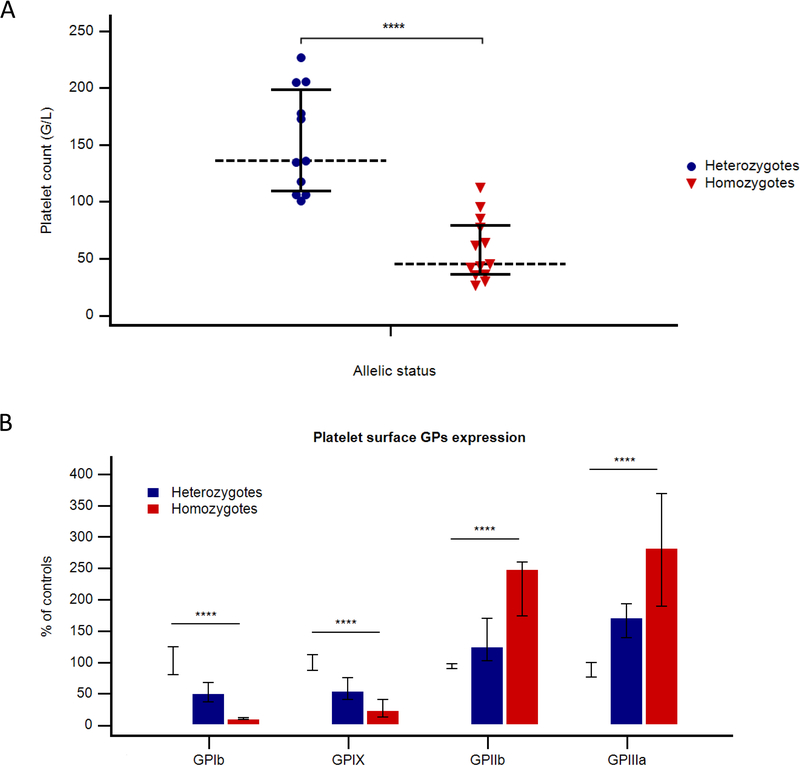

BSS patients had severe to minor macrothrombocytopenia, ranging from 26 to 112 ×109 L−1 (Median+/−SD: 45 +/− 27.2 ×109 L−1) (Fig. 2A). No correlation was observed between platelet count and ISTH bleeding score (p=0.37). Among heterozygous carriers, six (55%) had minor thrombocytopenia (< 150 ×109 L−1), whereas the remaining patients had normal platelet counts. When available, MPVs were normal or only slightly increased in this group. In BSS patients, GPIbα and GPIX expression, evaluated by flow cytometry on platelet membrane, was markedly reduced, whereas the level of the GPIIb-IIIa complex was twice normal, due to the increased platelet size (Fig. 2B). In heterozygous carriers, GPIb-IX complex was less, but also significantly reduced compared to controls (Fig. 2B). Finally, on a biological level, heterozygous patients had a high inter-individual variability regarding their platelet counts, whereas low GPIb-IX expression showed less variation, representing a good biological screening marker for these patients.

Figure 2. Biological characteristics of the population study according to allelic status.

(A) Platelet counts; (B) Platelet surface GPs expression measured by flow cytometry with different monoclonal antibodies. Horizontal bars represent medians and interquartiles. **** p<.0001.

In conclusion, this study identified a private mutation confined to a cluster of families from Reunion island. At a molecular level, this work further stresses the importance of the LRCT domain of the GPIbβ subunit for its proper folding and assembly with other subunits of the GPIb-IX complex. Moreover, clinical and biological data provided by this study may help improving the diagnosis and management of this dense BSS population from Reunion island.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Genealogical trees representation of BSS patients from Reunion families. Five families identified with the Asn89Asp mutation were subjected to genealogical analysis. Each individual was numbered randomly and correspondence to the families and patients can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

Supplemental Figure 2. Genetic defect of BSS patients from Reunion island and modeling of the Asn residue affected by the mutation. (A) Asn89Asp predicts alteration of a conserved residue in the C-terminal flanking sequence of the single LRR domain of GPIbβ (LLRCT), shown here aligned with orthologous sequences.

Mutated residue is highlighted in red. (B) 3-D modelling of the GPIbβ extracellular and LLRCT domains. The left panel shows the GPIbβ extracellular domain structure in ribbon diagram, in rainbow color (N-terminus: blue; C terminus: red). The side chain of Asn89 is shown in ball-and-stick model. The right panel provides a close-up view of the extensive hydrogen bond network surrounding the side chain of Asn89 and is at the similar view point as the left panel.

The oxygen atoms are shown in red, and nitrogen ones in blue. The side chain of Asn89 forms 6 close-knit hydrogen bonds with polar backbone atoms. Specifically, the OD1 atom in Asn89 is located within hydrogen bond distance of the N atom of Leu67, the N and O atoms of Asn65. The ND2 atom in Asn89 is close to backbone O atoms of Leu62, Leu86 and Gly87. Each pairwise distance in angstrom is marked in the figure. Note that these hydrogen bonds are between Asn89 and residues from the preceding layer, or between Asn89 (after the turn) and residues before the turn in the same layer.

Supplemental Figure 3. Western blots of platelet protein extracts from BSS1 patient and a normal control (C) run in nonreducing conditions. Platelet lysates were analyzed with anti-GPIbα (Bx-1), anti-GPIX (FMC25) and anti-GPIbβ (MBC 257.4) MoAbs. Patient’s platelets showed trace amounts of GPIbβ and absence of GPIbα and GPIX.

Acknowledgements

R. Li is supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant HL082808.

Footnotes

Addendum

H. Randrianaivo-Ranjatoelina, C. De Thoré, M. Dreyfus, C. Lavenu-Bombled, and M. Fiore followed patients and collected data; ML Jacquemont collected genealogic information and established the genealogic trees; M.J. Baas and A. Dupuis performed sequencing; R. Li performed 3-D modelling; C. Gachet, critically reviewed the manuscript; F. Lanza and M. Fiore designed the study, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Bragadottir G, Birgisdottir ER, Gudmundsdottir BR, Hilmarsdottir B, Vidarsson B, Magnusson MK, Larsen OH, Sorensen B, Ingerslev J & Onundarson PT (2015) Clinical phenotype in heterozygote and biallelic Bernard-Soulier syndrome--a case control study. Am J Hematol, 90, 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza F (2006) Bernard-Soulier syndrome (hemorrhagiparous thrombocytic dystrophy). Orphanet J Rare Dis, 1, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan PA, Yang W, Carr KH, Mo X, Zheng X, Li R & Emsley J (2011) Quaternary organization of GPIb-IX complex and insights into Bernard-Soulier syndrome revealed by the structures of GPIbbeta and a GPIbbeta/GPIX chimera. Blood, 118, 5292–5301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurden A & Nurden P (2011) Advances in our understanding of the molecular basis of disorders of platelet function. J Thromb Haemost, 9 Suppl 1, 76–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard I, Broux O, Allamand V, Fougerousse F, Chiannilkulchai N, Bourg N, Brenguier L, Devaud C, Pasturaud P, Roudaut C & et al. (1995) Mutations in the proteolytic enzyme calpain 3 cause limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Cell, 81, 27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodius F, Duclos F, Wrogemann K, Le Paslier D, Ougen P, Billault A, Belal S, Musenger C, Brice A, Durr A & et al. (1994) Recombinations in individuals homozygous by descent localize the Friedreich ataxia locus in a cloned 450-kb interval. Am J Hum Genet, 54, 1050–1059. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savoia A, Pastore A, De Rocco D, Civaschi E, Di Stazio M, Bottega R, Melazzini F, Bozzi V, Pecci A, Magrin S, Balduini CL & Noris P (2011) Clinical and genetic aspects of Bernard-Soulier syndrome: searching for genotype/phenotype correlations. Haematologica, 96, 417–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strassel C, Pasquet JM, Alessi MC, Juhan-Vague I, Chambost H, Combrie R, Nurden P, Bas MJ, De La Salle C, Cazenave JP, Lanza F & Nurden AT (2003) A novel missense mutation shows that GPIbbeta has a dual role in controlling the processing and stability of the platelet GPIb-IX adhesion receptor. Biochemistry, 42, 4452–4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Genealogical trees representation of BSS patients from Reunion families. Five families identified with the Asn89Asp mutation were subjected to genealogical analysis. Each individual was numbered randomly and correspondence to the families and patients can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

Supplemental Figure 2. Genetic defect of BSS patients from Reunion island and modeling of the Asn residue affected by the mutation. (A) Asn89Asp predicts alteration of a conserved residue in the C-terminal flanking sequence of the single LRR domain of GPIbβ (LLRCT), shown here aligned with orthologous sequences.

Mutated residue is highlighted in red. (B) 3-D modelling of the GPIbβ extracellular and LLRCT domains. The left panel shows the GPIbβ extracellular domain structure in ribbon diagram, in rainbow color (N-terminus: blue; C terminus: red). The side chain of Asn89 is shown in ball-and-stick model. The right panel provides a close-up view of the extensive hydrogen bond network surrounding the side chain of Asn89 and is at the similar view point as the left panel.

The oxygen atoms are shown in red, and nitrogen ones in blue. The side chain of Asn89 forms 6 close-knit hydrogen bonds with polar backbone atoms. Specifically, the OD1 atom in Asn89 is located within hydrogen bond distance of the N atom of Leu67, the N and O atoms of Asn65. The ND2 atom in Asn89 is close to backbone O atoms of Leu62, Leu86 and Gly87. Each pairwise distance in angstrom is marked in the figure. Note that these hydrogen bonds are between Asn89 and residues from the preceding layer, or between Asn89 (after the turn) and residues before the turn in the same layer.

Supplemental Figure 3. Western blots of platelet protein extracts from BSS1 patient and a normal control (C) run in nonreducing conditions. Platelet lysates were analyzed with anti-GPIbα (Bx-1), anti-GPIX (FMC25) and anti-GPIbβ (MBC 257.4) MoAbs. Patient’s platelets showed trace amounts of GPIbβ and absence of GPIbα and GPIX.