Abstract

Background

The impact of lymphadenectomy extent on the survival of patients with primary resectable gastric carcinoma is debated.

Objectives

We aimed to systematically review and meta‐analyze the evidence on the impact of the three main types of progressively more extended lymph node dissection (that is, D1, D2 and D3 lymphadenectomy) on the clinical outcome of patients with primary resectable carcinoma of the stomach. The primary objective was to assess the impact of lymphadenectomy extent on survival (overall survival [OS], disease specific survival [DSS] and disease free survival [DFS]). The secondary aim was to assess the impact of lymphadenectomy on post‐operative mortality.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE until 2001, including references from relevant articles and conference proceedings. We also contacted known researchers in the field. For the updated review, CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE were searched from 2001 to February 2015.

Selection criteria

We considered randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the three main types of lymph node dissection (i.e., D1, D2 and D3 lymphadenectomy) in patients with primary non‐metastatic resectable carcinoma of the stomach.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data from the included studies. Hazard ratios (HR) and relative risks (RR) along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were used to measure differences in survival and mortality rates between trial arms, respectively. Potential sources of between‐study heterogeneity were investigated by means of subgroup and sensitivity analyses. The same two authors independently assessed the risk of bias of eligible studies according to the standards of the Cochrane Collaboration and the quality of the overall evidence based on the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) criteria.

Main results

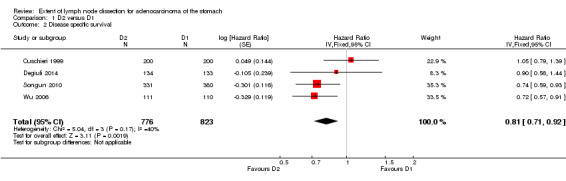

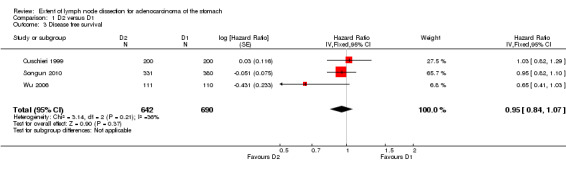

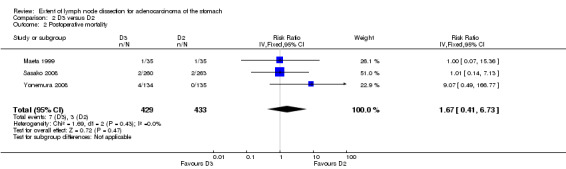

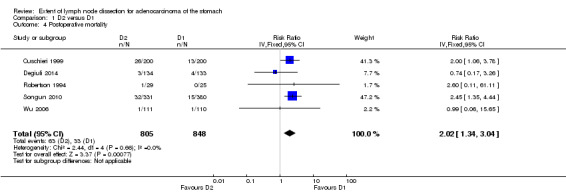

Eight RCTs (enrolling 2515 patients) met the inclusion criteria. Three RCTs (all performed in Asian countries) compared D3 with D2 lymphadenectomy: data suggested no significant difference in OS between these two types of lymph node dissection (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.21), with no significant difference in postoperative mortality (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.73). Data for DFS were available only from one trial and for no trial were DSS data available. Five RCTs (n = 3 European; n = 2 Asian) compared D2 to D1 lymphadenectomy: OS (n = 5; HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.17) and DFS (n=3; HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.07) findings suggested no significant difference between these two types of lymph node dissection. In contrast, D2 lymphadenectomy was associated with a significantly better DSS compared to D1 lymphadenectomy (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.92), the quality of the body of evidence being moderate; however, D2 lymphadenectomy was also associated with a higher postoperative mortality rate (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.34 to 3.04).

Authors' conclusions

D2 lymphadenectomy can improve DSS in patients with resectable carcinoma of the stomach, although the increased incidence of postoperative mortality reduces its therapeutic benefit.

Plain language summary

Extent of lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric cancer

Review question

Does more extended lymphadenectomy lead to a survival advantage for patients undergoing surgery for gastric carcinoma?

Background

Gastric carcinoma is a leading cause of cancer death worldwide. For patients affected with this disease, the main therapy is surgery, which consists of gastric resection along with the removal of lymph nodes surrounding the stomach (a procedure called lymphadenectomy). Three types of progressively more extended lymphadenectomies exist (called D1, D2 and D3); their therapeutic benefit is debated.

Study characteristics

We collected data from eight randomized controlled trials addressing this issue and enrolling a total of 2515 patients.

Key results

We found that D2 lymphadenectomy can reduce the number of deaths due to disease progression as compared to D1 lymphadenectomy. However, D2 lymphadenectomy was also associated with a higher rate of postoperative mortality. In addition, available evidence does not support the superiority of D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy. In conclusion, our findings support the use of D2 lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable carcinoma of the stomach, although the increased incidence of postoperative mortality reduces its therapeutic effect.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was moderate due to an intermediate level of result heterogeneity across the included trials.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Gastric carcinoma ranks fifth among the most common cancers and third among the most frequent causes of cancer death worldwide (Ferlay 2014). Surgery remains the only intervention known to produce cure or long‐term survival when used alone (Hartgrink 2009; Blum 2013). The prognosis after macroscopically (R1) and microscopically (R0) complete resection is strongly related to penetration of the primary tumor through the stomach wall (T‐stage) and lymph node involvement (N‐stage). Reported five‐year survival rates range from over 90% in intramucosal cancer to about 20% in patients with lymph node metastatic disease. In view of the poor survival rates for more advanced disease, additional treatment options (i.e., adjuvant or postoperative chemotherapy) are recommended for patients at high risk of disease recurrence and death, such as those with lymph node metastasis (Hartgrink 2009; Blum 2013).

Description of the intervention

The role of surgery is not only to remove the primary tumor but also the locoregional lymph nodes (i.e., the lymph nodes that drain the lymph of the affected organ), as these may contain metastatic deposits. A limited dissection removes only the nodal groups strictly adjacent to the stomach (so called D1 lymph node dissection), whereas more extended operations also remove the nodes along the three branches (i.e., the left gastric artery, the splenic artery and the hepatic artery) of the coeliac axis (so called D2 lymphadenectomy). When even more distant lymph nodes are removed (i.e., para‐aortic lymph nodes) the lymph node dissection is named D3 lymphadenectomy. The value of surgical dissection to remove the draining lymph nodes has been controversial for decades (Akagi 2011; Allum 2012; Blum 2013; Giuliani 2014; Hartgrink 2009; Saka 2011; Steur 2013). Japanese surgeons routinely perform the more extended (i.e., D2 or D3) as opposed to the more limited (D1) lymph node dissection, reasoning that the tumor is known to disseminate outwards in an orderly fashion through lymphatic channels from the stomach (Soga 1979). Therefore, more extended lymph node dissection should theoretically provide patients with a better chance of survival via two distinct mechanisms. First, removal of more lymph nodes should guarantee a more accurate disease staging (N‐stage; Arigami 2013), which can indirectly improve survival by identifying patients with high risk of disease recurrence who can benefit most from adjuvant therapy. Second, more extended lymphadenectomy should increase the likelihood of removing microscopic metastatic deposits that are responsible for disease relapse (Arigami 2013). In this regard, some non‐randomized studies have reported promising survival findings for D2 as compared to D1 surgery (Onate‐Ocana 2000; Viste 1994; Volpe 2000). However, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the three types of lymph node dissection (i.e., D1, D2 and D3) have shown no definitive difference in terms of survival (Steur 2013; Giuliani 2014). In fact, most studies provide consistent evidence of increased postoperative morbidity and mortality for more extended lymph node dissection (Allum 2012; Giuliani 2014; Steur 2013).

Why it is important to do this review

Available evidence does not univocally support the routine implementation of more extended lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric cancer, since the survival advantage is unclear. Moreover, it is widely acknowledged that more aggressive surgery is followed by higher rates of postoperative complications. As a consequence, international guidelines addressing the best surgical approach to lymph node dissection in gastric cancer patients are more opinion‐based than evidence‐based (Verlato 2014). In addition, no meta‐analysis performed so far has comprehensively addressed the issue of survival (i.e. time‐to‐event) data. Therefore, we tried to fill this gap of the medical literature.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness of the three different types of lymphadenectomy (i.e., D1, D2 and D3) in patients with primary (non‐metastatic) resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, according to the evidence from available RCTs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered RCTs comparing the efficacy of different types of lymphadenectomy (i.e., D1, D2, and D3) in patients undergoing surgery for resectable primary (non‐metastatic) gastric adenocarcinoma.

Types of participants

Patients undergoing surgery for resectable primary (non‐metastatic) adenocarcinoma of the stomach.

Types of interventions

We considered RCTs comparing the three following types of lymphadenectomy for primary gastric cancer:

D1 type lymphadenectomy: only lymph nodes adherent to the stomach (also known as perigastric lymph nodes) are removed during surgery.

D2 type lymphadenectomy: in addition to perigastric lymph nodes, lymph nodes located along the three branches of the coeliac axis (i.e., left gastric artery, splenic artery and hepatic artery) are removed during surgery.

D3 type lymphadenectomy: in addition to lymph nodes harvested in D1 and D2 type lymphadenectomy, lymph nodes located around the aorta (also known as periaortic lymph nodes) are removed during surgery.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Overall survival (OS; time from surgery to either death by any cause or last follow up).

Disease‐specific survival (DSS; time from surgery to either death by disease or last follow up).

Disease‐free survival (DFS; time from surgery to either disease recurrence or last follow up).

Secondary outcomes

Postoperative mortality (within 30 days from surgery).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Searches were performed in February 2015. The search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE are described in detail in Appendix 1, Appendix 2 and Appendix 3, respectively.

Searching other resources

Reference lists from trials selected by electronic searching were handsearched to identify further potentially relevant studies. In addition, colleagues in the field of surgery, gastroenterology and oncology were contacted and asked to provide details of published or unpublished RCTs.

Data collection and analysis

We followed the PRISMA (Liberati 2009) and Cochrane (Higgins 2011) guidelines for the conduct of systematic reviews of interventions.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SM and DN) independently screened the retrieved abstracts identified through the above described searches to assess eligibility. If eligibility was unclear upon reading the abstract, the full paper was retrieved to determine its inclusion or exclusion. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

For a study to be eligible, the full text of the article describing that study had to report time‐to‐event data on at least one of the chosen primary outcomes (i.e., OS, DSS and DFS).

Data extraction and management

Included articles were reviewed and data extracted using a dedicated spreadsheet. The following data were extracted from each study:

First author, year of publication and country.

Type of comparison (D1 vs D2, D2 vs D3, D1 vs D3).

Patients enrolled (total and per randomization arm).

Survival outcome(s) (OS, DSS, DFS) time‐to‐event data.

Length of follow‐up.

Postoperative mortality.

Eligibility criteria.

Disease stage.

Data for assessing risk of bias.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool was adopted to assess the risk of bias for each RCT (Higgins 2011). Information regarding the following issues were extracted from each study report in order to assess risk of bias:

Method of randomization.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants (in this setting no blinding is possible for surgeons).

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data (including withdrawals and losses to follow‐up).

Selective outcome reporting.

Intention‐to‐treat or per‐protocol reporting.

The quality of each study was also assessed by considering whether investigators included sample size calculation in the study design and whether the calculated sample size was actually reached at the end of the study.

In order to assess the adequacy of the overall sample size (i.e., across the pooled trials) in terms of survival, we considered that at least 1380 patients should be enrolled to detect a minimum therapeutic benefit of interest (HR equal to or lower than 0.80) with a sufficient statistical power (80%), setting the alpha level of significance at 5% and considering an average five‐year survival rate in the control population (patients undergoing D1 lymphadenectomy) equal to 50%, as calculated by using the Stata 11.2 SE statistical software (StataCorp 2015). In order to assess the adequacy of the overall sample size (i.e., across the pooled trials) in terms of postoperative mortality, we considered that at least 1200 patients should be enrolled to detect a minimum harm of interest (RR equal to or higher than 2) with a sufficient statistical power (80%), setting the alpha level of significance at 5% and considering an average postoperative mortality rate in the control population (patients undergoing D1 lymphadenectomy) equal to 4%. Sample size considerations were also applied to assess the quality of the body of evidence. Sample size calculations were made by using the Stata 11.2 SE statistical software (StataCorp 2015).

Measures of treatment effect

Regarding primary outcomes (i.e., OS, DSS, DFS), time‐to‐event data were considered in order to compare the efficacy of different types of lymphadenectomy. To this aim, hazard ratios (HR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were extracted from each study. When they were not reported in the study article, HRs were calculated from Kaplan‐Meier survival curves (if available; Parmar 1998).

With regard to the secondary outcome (postoperative mortality), mortality rates between randomization arms were compared using relative risk (RR).

Dealing with missing data

We performed the analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis whenever data were permissive. Otherwise, we performed a per‐protocol analysis as presented in the original study report. If missing data were essential to the analysis (i.e., time‐to‐event data), we tried to contact the authors of the original article to retrieve the missing information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Between‐study heterogeneity was measured using the widely known I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). Heterogeneity is usually deemed low, moderate or high if the I2 is lower than 25%, between 25% and 50% or greater than 50%, respectively. In cases of high heterogeneity, we interpreted the summary effect with caution. The Cochran's Q test was adopted to formally test the hypothesis that heterogeneity was different from null (although the amount of heterogeneity ‐ as measured by the I2 statistic ‐ is believed to be more informative than the demonstration of its occurrence). To be more conservative, we considered that heterogeneity was present when the Cochran's Q test P value was lower than 0.1.

Assessment of reporting biases

The small study bias (which includes publication bias) was investigated by means of visual inspection of funnel plots of trial size against treatment effect. Funnel plot asymmetry was not formally tested using Egger's regression test (Egger 1997) because fewer than 10 studies were available (Sterne 2011).

Data synthesis

Statistical analysis was carried out using RevMan version 5.2 (RevMan 2008). For time‐to‐event data, pooled hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were utilized to provide summary estimates of the relative therapeutic effect of different types of lymphadenectomy. For dichotomous data, pooled risk ratios (RRs) and corresponding 95% CIs were utilized to compare mortality rates associated with different types of lymphadenectomy. Summary estimates were calculated using the fixed‐effect model; however, in cases of high between‐study heterogeneity, the random‐effects model was adopted. In all cases, the inverse variance method was used to weight the studies.

In order to provide readers with information on the absolute effect of treatment on patient outcomes, the number needed to treat (NNT; the number of patients needed to be treated in order to avoid one event of interest) was calculated for the survival endpoint (Altman 1999) and the number needed to harm (NNH; the number of patients needed to be treated in order to cause an adverse event of interest) for the postoperative mortality endpoint.

Finally, the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system was employed to grade the quality of evidence into four levels: high quality, moderate quality, low quality and very low quality (Guyatt 2011). According to this system, the quality can be downgraded by one level (serious concern) or two levels (very serious concern) for the following reasons: risk of bias (see above section), inconsistency (unexplained heterogeneity, inconsistency of results), indirectness (indirect population, intervention, control, outcomes) and imprecision (wide confidence intervals). The quality can also be upgraded by one level if a large summary effect is found (we chose HR < 0.8) or if a linear relationship between extent of lymphadenectomy and survival improvement is observed.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analysis was planned to investigate whether between‐study heterogeneity (if present) depends upon different underlying effects of treatment (i.e., extent of lymph node dissection) across subgroups of RCTs defined by study‐level covariates. The only pre‐defined grouping covariate was the location of the country in which the study was performed (Asian versus European).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was employed to further investigate potential sources of between‐study heterogeneity. To this aim, leave‐one‐out sensitivity analysis (by excluding one RCT at a time) and sensitivity analysis by exclusion of low quality studies (as defined by the presence of high risk of bias in one or more domains of Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool) were performed.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

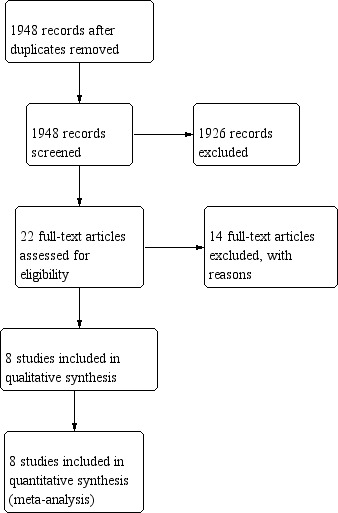

The initial search yielded 1948 reports (after removing duplicates). After title/abstract screening, we retrieved the full text of 18 articles potentially eligible. In two articles, no survival data were reported which led to their exclusion (Dent 1988; Kulig 2007). In one article, the authors compared D2 lymphadenectomy with a modified (less extended) D2 lymphadenectomy, which made this RCT ineligible (Galizia 2015). For five trials the results were published in multiple articles at different time points: therefore, we included the most recent versions (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Sasako 2008; Songun 2010; Wu 2006). In the end, eight RCTs were included for qualitative and quantitative analysis (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Eight RCTs (enrolling 2515 patients) met the inclusion criteria (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Maeta 1999; Robertson 1994; Sasako 2008; Songun 2010; Wu 2006; Yonemura 2008). The main features of these studies are reported in the Characteristics of included studies table. In five RCTs (n = 1653) D2 lymphadenectomy was compared to D1 lymphadenectomy (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Robertson 1994; Songun 2010; Wu 2006); among these five studies, three were from European countries (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Songun 2010) and two were from Asian countries (Robertson 1994; Wu 2006). D3 lymphadenectomy was compared to D2 lymphadenectomy in three RCTs from Japan (n = 862; Maeta 1999; Sasako 2008; Yonemura 2008). The main inclusion criteria (resectable non metastatic gastric carcinoma) was common to all eight trials. Overall, the baseline characteristics of enrolled patients appeared similar, although the disease stage was not always reported in detail. Regarding outcomes, OS data were always reported; DSS data were available from four RCTs (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Songun 2010; Wu 2006); and DFS data were available from four (Cuschieri 1999; Sasako 2008; Songun 2010; Wu 2006). In three articles, hazard ratios were not reported and thus were extrapolated from the reported Kaplan‐Meier survival curves (Maeta 1999; Robertson 1994; Yonemura 2008).

Excluded studies

The list of excluded trials (along with the main reasons for exclusion) is available in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

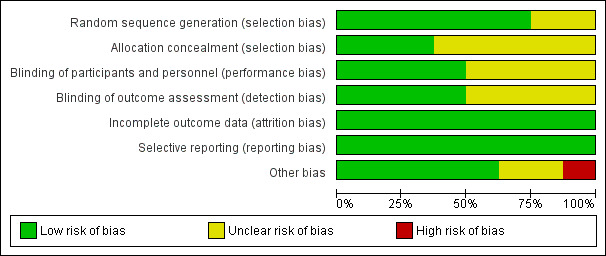

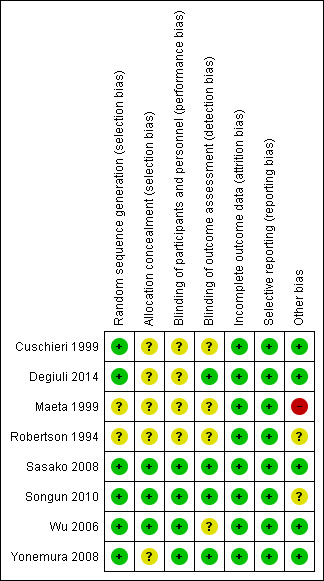

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of each bias across all studies and the risk of bias in each trial are reported in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Overall, the risk of selection bias was low in terms of random sequence generation; however, information on allocation concealment was missing in most studies.

Blinding

In this setting, blinding was only possible for participants (obviously surgeons could not be blinded to the type of lymphadenectomy). Information on blinding of participants (performance bias) and blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) was unreported in half of all studies.

Incomplete outcome data

The risk of attrition bias was low in all studies.

Selective reporting

The risk of reporting bias was low in all studies.

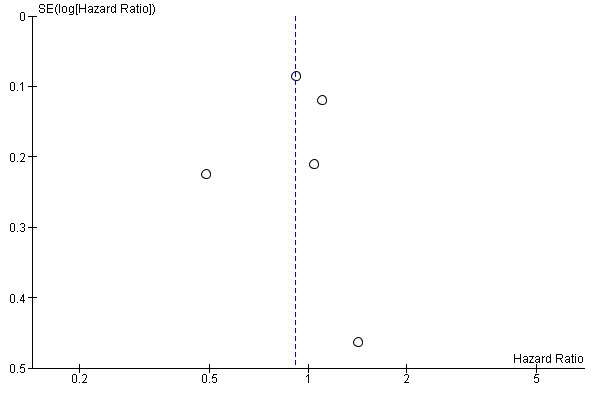

Other potential sources of bias

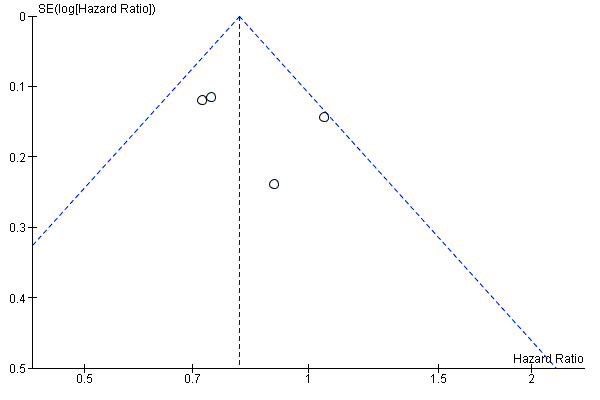

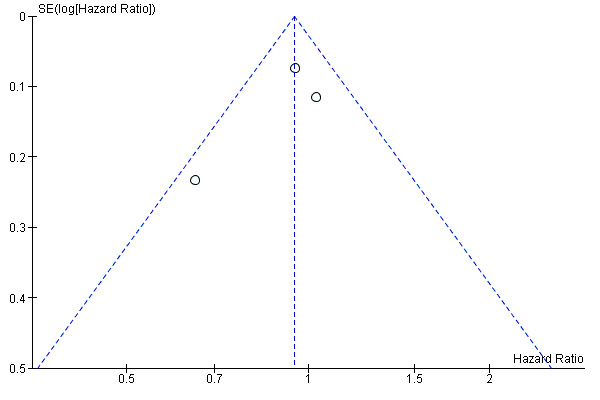

Since fewer than 10 trials were available, small study bias was assessed only by visual inspection of funnel plots for OS (Figure 4), DSS (Figure 5) and DFS (Figure 6), no gross asymmetry being detected.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy, outcome: overall survival.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy, outcome: disease specific survival.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy, outcome: disease free survival.

Sample size calculation was not reported in two RCTs in which the low number of patients enrolled (< 100, which does not allow the detection of any reasonable survival difference in this setting) raises the suspicion that no sample size calculation was performed (Maeta 1999; Robertson 1994).

In one trial the description of the methods is quite scarce, which raises some doubt about the soundness of the design and conduction of the trial (Maeta 1999).

Finally, in one trial the number of patients excluded from analysis after randomization (mainly due to non resectable disease) is quite higher than in the other trials, which was likely due to the fact that randomization was performed before surgery (disease resectability can only be verified during surgery); the ultimate impact of this circumstance on the outcomes is unclear (Songun 2010).

Effects of interventions

for the main comparison.

| D3 lymphadenectomy compared with D2 lymphadenectomy for primary gastric carcinoma | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with resectable disease Settings: randomized controlled trials Intervention: D3 lymphadenectomy Comparison: D2 lymphadenectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative risk (95% CI) | No of Participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| D2 | D3 | |||||

|

Overall survival (surviving rates) |

Medium risk population | HR: 0.99 (0.81 to 1.21) | 862 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate** | Assumed risk calculated based on the average 5‐year overall survival rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (54%). | |

| 540 per 1000 | 543 per 1000 (474 to 607) | |||||

|

Postoperative mortality (within 30 days from surgery) |

Medium risk population | RR: 1.67 (0.41 to 6.73) | 862 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate** | Assumed risk calculated based on the average postoperative mortality rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (0.7%) | |

| 7 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (3 to 47) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

**The quality of the body of evidence was downgraded due to the insufficient sample size and the lack of data on other survival endpoints (disease specific and disease free survival). CI: Confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RR: relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

2.

| D2 lymphadenectomy compared with D1 lymphadenectomy for primary gastric carcinoma | ||||||

|

Patient or population: patients with resectable disease Settings: randomized controlled trials Intervention: D2 lymphadenectomy Comparison: D1 lymphadenectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (trials) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| D1 | D2 | |||||

|

Overall survival (surviving rates) |

Medium risk population |

HR: 0.91 (0.71 to 1.17) |

1653 (5) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low** | Assumed risk calculated based on the average 5‐year overall survival rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (49%). | |

| 490 per 1000 | 522 per 1000 (434 to 603) | |||||

|

Disease specific survival (surviving rates) |

Medium risk population |

HR: 0.81 (0.71 to 0.92) |

1599 (4) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate*** | Assumed risk calculated based on the average 5‐year disease specific survival rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (58%). | |

| 580 per 1000 | 643 per 1000 (606 to 679) | |||||

|

Disease free survival (surviving rates) |

Medium risk population |

HR: 0.95 (0.84 to 1.07) |

1332 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate**** | Assumed risk calculated based on the average 5‐year disease free survival rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (44%). | |

| 440 per 1000 | 458 per 1000 (415 to 502) | |||||

|

Postoperative mortality (within 30 days from surgery) |

Medium risk population |

RR: 2.02 (1.34 to 3.04) |

1653 (5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | Assumed risk calculated based on the average mortality rate observed in the control arms of the included trials (3.9%). | |

| 39 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (52 to 118) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

**The quality of the body of evidence was downgraded due to high between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on disease specific survival, which did result superior for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy. ***The quality of the body of evidence was downgraded due to intermediate between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on overall and disease free survival, which did not result superior for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy ****The quality of the body of evidence was downgraded due to intermediate between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on disease specific survival, which did result superior for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy CI: Confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio; RR: relative risk | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

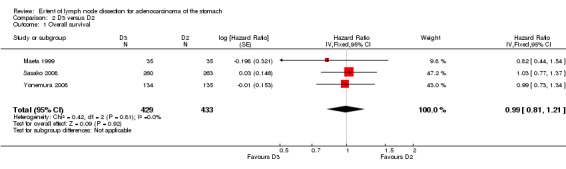

Overall survival (OS)

Considering the comparison between D3 and D2 lymphadenectomy, none of the three available RCTs showed a significant impact of lymphadenectomy extent on OS. Meta‐analysis of these three RCTs (n = 862) confirmed the lack of statistically significant association between type of lymph node dissection and OS (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.21), with no between‐study heterogeneity, as shown in Analysis 2.1.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 D3 versus D2, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

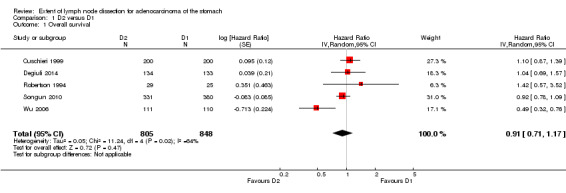

Considering the comparison between D2 and D1 lymphadenectomy, only one of the five available RCTs showed a significant advantage of D2 lymphadenectomy in terms of OS (Wu 2006). The meta‐analysis of these five RCTs (n = 1653) confirmed the lack of statistically significant association between type of lymph node dissection and OS (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.17), as shown in Analysis 1.1. This meta‐analysis was characterized by remarkable between‐study heterogeneity (I2 64%), which was almost completely sustained by the above mentioned RCT reporting a significant OS benefit of D2 over D1 lymphadenectomy (Wu 2006). From subgroup meta‐analysis, we found that trials performed in Asian countries (Robertson 1994; Wu 2006) had high between‐study heterogeneity (I2 76%), whereas trials carried out in European countries (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Songun 2010) were highly homogeneous (I2 0%). Neither Asian trials (HR 0.77, 95% CI 0.28 to 2.17) nor European trials (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.12) showed any statistically significant effect of lymph node dissection extent on OS. Sensitivity analysis showed that results were highly homogeneous (I2 0%) when the Wu 2006 trial was excluded, with no significant impact of type of lymph node dissection on patients' OS (HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.12).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 D2 versus D1, Outcome 1 Overall survival.

Disease specific survival (DSS)

Considering the comparison between D2 and D1 lymphadenectomy (no data were available for the D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy), two out of four RCTs showed a significant advantage of D2 lymphadenectomy in terms of DSS (Songun 2010; Wu 2006). The meta‐analysis of these four RCTs (n = 1599) confirmed the significant DSS benefit for patients undergoing D2 lymph node dissection (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.92), as shown in Analysis 1.2. This meta‐analysis was characterized by moderate between‐study heterogeneity (I2 40%), which basically disappeared when the Songun 2010 trial was excluded. Results did not change when the random‐effects model was applied (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.98).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 D2 versus D1, Outcome 2 Disease specific survival.

Considering a five‐year survival rate equal to 50% for patients treated with D1 lymphadenectomy (i.e., the average five‐year survival rate reported in the four RCTs), the NNT was equal to 14 (95% CI 9 to 35), which means that about 71 events (i.e., deaths by disease) would be avoided per 1000 patients treated with D2 (instead of D1) lymph node dissection.

Sensitivity analysis showed that the inclusion of both Songun 2010 (Dutch) and Wu 2006 (Taiwanese) were necessary for the association between D2 lymphadenectomy and improved DSS to be statistically significant. Accordingly, the subgroup meta‐analysis of the three trials carried out in European countries (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Songun 2010) showed no statistically significant association between lymphadenectomy extent and DSS (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.01).

Disease free survival (DFS)

Considering the comparison between D3 and D2 lymphadenectomy, only one RCT was available, showing no significant impact of lymphadenectomy extent on DFS (HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.42; Sasako 2008).

Considering the comparison between D2 and D1 lymphadenectomy, none of the three RCTs demonstrated a significant advantage of D2 lymphadenectomy in terms of DFS (Cuschieri 1999; Songun 2010; Wu 2006). The meta‐analysis of these three RCTs (n = 1332) confirmed the lack of statistically significant DFS benefit for patients undergoing D2 lymph node dissection (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.07), as shown in Analysis 1.3. This meta‐analysis was characterized by moderate between‐study heterogeneity (I2 36%), the potential source of which remaining undetermined.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 D2 versus D1, Outcome 3 Disease free survival.

Postoperative mortality

Meta‐analysis of the three available RCTs (Maeta 1999; Sasako 2008; Yonemura 2008) showed no significant difference in terms of postoperative mortality rate between D3 and D2 lymphadenectomy (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.41 to 6.73); no between‐study heterogeneity was observed (I2 0%; Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 D3 versus D2, Outcome 2 Postoperative mortality.

Regarding the D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy comparison, the meta‐analysis of the five available RCTs (Cuschieri 1999; Degiuli 2014; Robertson 1994; Songun 2010; Wu 2006) showed a significantly increased risk of postoperative mortality rate among patients undergoing D2 as compared to those undergoing D1 lymph node dissection (RR 2.02, 95% CI 1.34 to 3.04); no between‐study heterogeneity was observed (I2 0%; Analysis 1.4). Considering that the average mortality rate in the D1 and D2 arms was 33/848 (3.9%) and 63/805 (7.8%), respectively, the number needed to harm (NNH) was 26 (95% CI 16 to 60), which means that about 38 events (i.e., postoperative deaths) would be caused per 1000 patients treated with D2 (instead of D1) lymph node dissection.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 D2 versus D1, Outcome 4 Postoperative mortality.

Discussion

Summary of main results

By analyzing the data from eight RCTs enrolling 2515 patients, we found that D3 lymphadenectomy is not associated with a survival advantage as compared to D2 lymphadenectomy in patients with resectable primary carcinoma of the stomach. In contrast, a significant survival benefit was demonstrated for D2 type lymph node dissection as compared to D1 lymphadenectomy; however, this advantage was limited to DSS (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.92). D2 lymphadenectomy was also associated with a significantly increased risk of postoperative mortality, which ultimately reduces the therapeutic benefit. As a rough measure of the balance between benefit and harm associated with D2 lymphadenectomy (as compared to D1 type lymph node dissection), we can consider the difference between deaths avoided (71/1000) and those caused (38/1000) by the more extended lymph node dissection, which would lead to a net benefit equal to 33 deaths avoided for every 1000 patients treated with D2 lymphadenectomy.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included trials directly addressed the review question (i.e. whether the extent of lymphadenectomy affects patients survival), however, some limitations of the available evidence must be noted.

First, not all RCTs reported on all possible survival outcomes (OS, DSS and DFS), as detailed in the Results section. This was particularly true for the D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy trials, from which only OS data could be meta‐analyzed. Regarding D2 versus D1 type of lymph node dissection, the lack of complete survival data prevented us from using all trials for all primary outcomes, which ultimately reduced the power for detecting relevant survival differences.

Second, in some trials patients were not allowed to receive either neoadjuvant (i.e., pre‐operative) or adjuvant (i.e., post‐operative) medical therapies (e.g., systemic chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy), and in others no data were reported on this subject. In light of the wide use of these complementary treatments in the current management of patients with gastric cancer, this is probably an important obstacle in interpreting the relevance of the present findings in terms of applicability to the "real world". In particular, it remains unclear whether the survival advantage associated with a more extended lymphadenectomy can be synergically combined with that of adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatments or whether they obviate each other (i.e., chemotherapy might make more extended lymph node dissection gratuitous, and vice versa). In this regard, trials designed to answer this question are eagerly awaited.

Third, the expertise of the surgeons performing lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric cancer is rarely reported, although it is deemed to represent an important determinant in patient clinical outcomes (Cuschieri 2014). Therefore, findings might be different from trials performed in highly specialized centers (with high caseloads).

Finally, the lack of evidence for the superiority of D3 vs D2 lymphadenectomy was based exclusively on Asian patients, which leaves undressed the issue of whether or not D3 lymphadenectomy is beneficial in Caucasian patients.

Quality of the evidence

The randomized controlled trials (RCTs) included in this review and meta‐analysis were overall of high quality. There was a serious concern of bias due to small sample size (insufficient to achieve adequate statistical power given a clinically meaningful survival difference between the two study arms) and lack of information describing the methodology in only one RCT (Maeta 1999).

According to the GRADE criteria, the body of evidence for each review endpoint was as follows (see Table 1; Table 2):

1) OS: the lack of superiority of D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy was supported by a moderate quality body of evidence. Downgrading was due to the fact that only 862 patients were enrolled in three RCTs, whereas at least 1380 patients should be enrolled to detect a minimum therapeutic benefit of interest (HR equal to or lower than 0.80). In addition, no data on other survival endpoints (i.e., disease specific and disease free survival) were available.

2) OS: the lack of superiority of D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy was supported by a low quality body of evidence (the downgrading was due to high between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on disease specific survival, which was higher for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy).

3) DSS: the superiority of D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy was supported by a moderate quality body of evidence (the downgrading was due to intermediate between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on overall and disease free survival, which was not higher for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy).

4) DFS: the lack of superiority of D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy was supported by a moderate quality body of evidence (the downgrading was due to intermediate between‐study heterogeneity as well as to the contrasting evidence on disease specific survival, which was higher for patients undergoing D2 lymphadenectomy).

5) Postoperative mortality: the lack of difference between D3 and D2 lymphadenectomy was supported by a moderate quality body of evidence. The downgrading was due to the insufficient sample size; only 862 patients were enrolled in three RCTs, whereas at least 1200 patients should be enrolled to detect a minimum harm of interest (RR equal or higher than 2).

6) Postoperative mortality: the higher rate of mortality observed in patients undergoing D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy was supported by a high quality body of evidence.

Potential biases in the review process

The thorough literature search should have identified all relevant trials. However, the possibility always exists that RCTs have been carried out but remain unreported or reported either in meeting abstracts or in articles published in journals not indexed in the databases we screened. These may be factors within, or outside, the control of the review authors.

As regards data availability, only an international collaboration leading to the sharing of original data and allowing an individual patient data meta‐analysis might overcome the lack of data regarding DSS and DFS in some trials. Moreover, hazard ratios utilized for meta‐analysis were not always adjusted by well established confounding factors (e.g., disease stage), as is the case for hazard ratios extrapolated from Kaplan‐Meier survival curves. Once again, only an individual patient data meta‐analysis might enable investigators to uniformly adjust survival data and thus provide readers with an unbiased meta‐analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

None of the previous meta‐analyses dedicated to this subject demonstrated a survival advantage for patients undergoing more extended lymphadenectomy (El‐Sedfy 2014; Jiang 2013; Jiang 2014; Memon 2011; Seevaratnam 2012; Yang 2009). However, none of the previous meta‐analyses took into consideration the DSS, which is the outcome we found associated with a therapeutic benefit in patients undergoing D2 (as compared to those undergoing D1) lymphadenectomy. Moreover, most previous meta‐analyses used odds ratio instead of hazard ratio as the effect measure: this method can be misleading since the same number of events in two study arms can occur at a very different average time, which can make the actual survival of the two patient groups very different. This, coupled with the fact that survival data may be censored, makes the hazard ratio the best way of describing time‐to‐event data such as survival data. Finally, not all previous meta‐analyses included the Cuschieri 1999 trial (for unclear reasons) and none of the previous meta‐analyses could consider the latest data from the Degiuli 2014 trial (which was published after their search dates).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our findings suggest that D2 lymphadenectomy might be currently considered the best surgical option for patients with primary resectable carcinoma of the stomach based on the observed significant benefit in terms of DSS. Since this type of lymph node dissection is associated with increased postoperative mortality (as compared to more limited lymphadenectomy) and in light of the fact that most of the associated mortality is ascribed to the resection of the spleen and of the pancreatic tail, we suggest that D2 lymphadenectomy should be performed without the splenopancreasectomy component. This suggestion ‐ already reported in the international literature (Brar 2012) ‐ is supported by the findings of a recently published RCT specifically addressing this issue (Galizia 2015), where patients undergoing a modified D2 lymphadenectomy (i.e., without splenopancreasectomy) had the same survival outcome as those undergoing standard D2 lymphadenectomy (i.e., including splenopancreasectomy) but had lower morbidity and mortality rates.

Implications for research.

The findings of the present review underscore the need for more research in this field. For instance, trials are warranted that investigate the relationship between the therapeutic effect of lymphadenectomy and that of currently available adjuvant (i.e., postoperative) and neoadjuvant (i.e., preoperative) chemo(radio)therapy. In fact, it is still unclear whether medical treatments may replace the potential therapeutic benefit of more extended lymphadenectomy, as well as whether the therapeutic effect of medical treatments can synergize with more extended lymph node dissection (Jansen 2012). Moreover, the role of sentinel node biopsy‐guided lymphadenectomy (Yashiro 2015) is still to be defined and might result in better management of patients with gastric cancer, as it does for melanoma and breast cancer patients. Finally, the comparison between D3 and D2 lymphadenectomy has thus far been carried out exclusively in Asian patients, which leaves room for similar comparisons in Caucasian patients.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 April 2015 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | We included six more randomized trials and the results did show a significant survival advantage for patients undergoing D2 as compared to D1 lymphadenectomy |

| 29 April 2015 | New search has been performed | The literature searches rerun and new evidence incorporated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2000 Review first published: Issue 4, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 December 2011 | Amended | Review withdrawn as authors no longer able to update. |

| 16 July 2009 | New search has been performed | Updated |

| 30 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 5 November 2004 | Amended | New studies found but not yet included or excluded. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Marta Briarava (Department of Surgery, Oncology and Gastroenterology, University of Padova, Padova, Italy) for setting up the database for the collection and analysis of the relevant data.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Stomach Neoplasms] explode all trees

#2 ((gastric or stomach) near/4 (cancer* or carcin* or malig* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or adenocarcinoma)):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#3 #1 or #2

#4 MeSH descriptor: [Survival] explode all trees

#5 MeSH descriptor: [Survival Analysis] explode all trees

#6 (surviv* or DFS or DSS):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#7 MeSH descriptor: [Mortality] explode all trees

#8 MeSH descriptor: [Death] explode all trees

#9 (death* or died or mortality or mortalities or deceased or dead* or fatal* or lethal):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#10 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9

#11 #3 and #10

#12 MeSH descriptor: [Lymph Nodes] explode all trees

#13 MeSH descriptor: [Lymph Node Excision] explode all trees

#14 (lymphadenectom* or lymph node* or LN or LND or LNE):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#15 #12 or #13 or #14

#16 #11 and #15

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

1 exp Stomach Neoplasms/

2 ((gastric or stomach) adj4 (cancer* or carcin* or malig* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or adenocarcinoma)).ti,ab,kw.

3 1 or 2

4 exp Disease‐Free Survival/ or exp Survival Analysis/ or exp Survival/ or exp Survival Rate/

5 (surviv* or DFS or DSS).ti,ab,kw.

6 exp Hospital Mortality/ or exp Mortality/

7 exp Death/

8 (death* or died or mortality or mortalities or deceased or dead* or fatal* or lethal*).ti,ab,kw.

9 or/4‐8

10 3 and 9

11 exp Lymph Node Excision/ or exp Lymph Nodes/

12 (lymphadenectom* or lymph node* or LN or LND or LNE).ti,ab,kw.

13 11 or 12

14 10 and 13

15 randomized controlled trial.pt.

16 controlled clinical trial.pt.

17 random*.mp.

18 trial.ab.

19 groups.ab.

20 or/15‐19

21 14 and 20

22 case report/

23 case study/

24 exp animals/ not humans/

25 or/22‐24

26 21 not 25

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

1 exp stomach tumor/

2 ((gastric or stomach) adj4 (cancer* or carcin* or malig* or tumor* or tumour* or neoplas* or adenocarcinoma)).ti,ab,kw.

3 1 or 2

4 exp disease free survival/ or exp survival rate/ or exp cancer survival/ or exp disease specific survival/ or exp event free survival/ or exp cancer specific survival/ or exp survival/ or exp failure free survival/ or exp overall survival/

5 (surviv* or DFS or DSS).ti,ab,kw.

6 exp mortality/ or exp cancer mortality/

7 exp death/

8 (death* or died or mortality or mortalities deceased or dead* or fatal* or lethal*).ti,ab,kw.

9 or/4‐8

10 3 and 9

11 exp lymph node/

12 exp lymph node dissection/

13 (lymphadenectom* or lymph node* or LN or LND or LNE).ti,ab,kw.

14 11 or 12 or 13

15 10 and 14

16 random$.mp.

17 double‐blind$.mp. or blind$.tw.

18 clinical trial:.mp.

19 16 or 17 or 18

20 15 and 19

21 Case study/

22 case report/

23 exp animal/ not human/

24 21 or 22 or 23

25 20 not 24

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. D2 versus D1.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 5 | 1653 | Hazard Ratio (Random, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.71, 1.17] |

| 2 Disease specific survival | 4 | 1599 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.71, 0.92] |

| 3 Disease free survival | 3 | 1332 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.84, 1.07] |

| 4 Postoperative mortality | 5 | 1653 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.02 [1.34, 3.04] |

Comparison 2. D3 versus D2.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Overall survival | 3 | 862 | Hazard Ratio (Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.81, 1.21] |

| 2 Postoperative mortality | 3 | 862 | Risk Ratio (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.67 [0.41, 6.73] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Cuschieri 1999.

| Methods | Method of randomization: patients randomized centrally by use of random permuted blocks Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: 4% Method of allocation concealment: unreported Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: yes (expected number = 400) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 400 (D2 = 200, D1 = 200) Age (mean): 66 years Sex (M/F): 270/130 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age and stage distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D2 vs D1): HR 1.10, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.39 Disease specific survival (D2 vs D1): HR 1.05, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.39 Disease free survival (D2 vs D1): HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.29 Postoperative deaths: 26 (D2), 13 (D1) |

|

| Notes | Country: Hong Kong (China) Median follow‐up: 6.5 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported (for participants only; no blinding is possible for surgeons) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Degiuli 2014.

| Methods | Method of randomization: sequence generated by a random‐number table Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: 9 (D2), 5 (D1) Method of allocation concealment: unreported Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: yes (expected number: 320) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 267 (D2 = 134, D1 = 133) Age (mean): 63 years Sex (M/F): 131/136 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age and stage distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D2 vs D1): HR 1.04,95% CI 0.69 to 1.57 Disease specific survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.44 Postoperative deaths: 3 (D2), 4 (D1) |

|

| Notes | Country: Italy Median follow‐up: 8.8 years Number of patients enrolled did not reach the calculated sample size due to slow accrual |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported (for participants only; no blinding is possible for surgeons) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Maeta 1999.

| Methods | Method of randomization: unreported

Exclusion after randomization: unreported

Lost to follow‐up: none Method of allocation concealment: unreported Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: unreported (unlikely it was performed due to the small number of patients enrolled, insufficient for achieving an adequate statistical power given a clinically meaningful expected survival difference between study arms) |

|

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 70 (D3 = 35, D2 = 35) Age (mean): 60 years Sex (M/F): 41/29 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age and stage distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D3 vs D2): HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.54 Postoperative deaths: 1 (D3), 1 (D2) |

|

| Notes | Country: Japan Median follow‐up: 2.3 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported (for participants only; no blinding is possible for surgeons) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | High risk | Sample size is insufficient for achieving an adequate statistical power given a clinically meaningful expected survival difference between study arms. Moreover, the description of the methods is quite scarce leaving room for doubt about the soundness of the design and conduct of the trial. |

Robertson 1994.

| Methods | Method of randomization: "by opening a numbered, sealed envelope containing the treatment option. The treatment options were determined by random numbers generated on a personal computer." Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: none Method of allocation concealment: unreported Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: unreported (unlikely it was performed due to the small number of patients enrolled, insufficient for achieving an adequate statistical power given a clinically meaningful expected survival difference between study arms) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 54 (D1 = 25, D2 = 29) Age (mean): 59 years Sex (M/F): 42/12 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age and sex distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D2 vs D1): HR 1.42, 95% CI 0.57 to 3.52 Postoperative deaths: 1 (D2), 0 (D1) |

|

| Notes | Country: Hong‐Kong Median follow‐up: 2.2 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported (for participants only; no blinding is possible for surgeons) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unreported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Sample size is insufficient for achieving an adequate statistical power given a clinically meaningful expected survival difference between study arms. |

Sasako 2008.

| Methods | Method of randomization: "the surgeon contacted the [data center] by telephone to receive a randomly generated assignment" Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: none Method of allocation concealment: "the surgeon contacted the [data center] by telephone to receive a randomly generated assignment" Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: reported (expected number: 412) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 523 (D3 = 260, D2 = 263) Age (mean): 60 years Sex (M/F): 359/164 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age, sex and stage distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D3 vs D2): HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.37 Disease free survival (D3 vs D2): HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.42 Postoperative deaths: 2 (D3), 2 (D2) |

|

| Notes | Country: Japan Median follow‐up: 5.7 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Songun 2010.

| Methods | Method of randomization: "The sequence of randomisation was in blocks of six with stratification according to the participating centre." Exclusion after randomization: D1 = 133 (metastatic disease); D2 = 152 (metastatic disease) Lost to follow‐up: one Method of allocation concealment: "The sequence of randomisation was in blocks of six with stratification according to the participating centre." Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: reported (expected number: 1062) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 523 (D2 = 483, D1 = 513) Age < 70 years: 33% Sex (M/F): 401/310 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age, sex and stage distribution similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.92, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.09 Disease specific survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.93 Disease free survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.10 Postoperative deaths: 32 (D2), 15 (D1) |

|

| Notes | Country: Netherlands Median follow‐up: 15.2 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | It is unclear whether the number of patients excluded after randomization had any impact on the trial outcomes. |

Wu 2006.

| Methods | Method of randomization: "Eligible patients were randomized by means of permuted block randomization" Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: none Method of allocation concealment: "Eligible patients were randomized by means of permuted block randomization." Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: reported (expected number: 150) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 221 (D2 = 111, D1 = 110) Age (mean): 67 years Sex (M/F): 170/51 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age, sex, tumor location and comorbidity similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D2 versus D1 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.76 Disease specific survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.91 Disease free survival (D2 vs D1): HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.03 Postoperative deaths: 0 (D2), 0 (D1) |

|

| Notes | Country: Taiwan Median follow‐up: 7.9 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | unreported |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

Yonemura 2008.

| Methods | Method of randomization: "After the final assessment of eligibility, patients were enrolled randomly by a computer algorithm" Exclusion after randomization: none Lost to follow‐up: none Method of allocation concealment: "After the final assessment of eligibility, patients were enrolled randomly by a computer algorithm" Intention‐to‐treat analysis: yes Description of sample size calculation: reported (expected number: 227) | |

| Participants | Number randomly assigned: 269 (D2 = 134, D1 = 135) Age (mean): 63 years Sex (M/F): 181/88 Inclusion criteria: patients with resectable primary non‐metastatic gastric carcinoma Equivalence of baseline characteristics: age, sex, and type of gastrectomy similar for both groups |

|

| Interventions | D3 versus D2 lymphadenectomy (during gastrectomy) | |

| Outcomes | Overall survival (D3 vs D2): HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.34 Postoperative deaths: 4 (D3), 0 (D2) |

|

| Notes | Country: Japan Median follow‐up: 5 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | unreported |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | |

| Other bias | Low risk | |

D1: limited lymphadenectomy removing only the nodal groups strictly adjacent to the stomach D2: extended lymphadenectomy removing lymph nodes as in D1 plus the nodes along the three branches (i.e., the left gastric artery, the splenic artery and the hepatic artery) of the coeliac axis D3: extensive lymphadenectomy, removing lymph nodes as in D2 plus more distant lymph nodes (i.e., para‐aortic) M: male F: female HR: hazard ratio CI: confidence interval

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Bonenkamp 1992 | Duplicate of Songun 2010 |

| Bonenkamp 1999 | Duplicate of Songun 2010 |

| Bunt 1996 | Duplicate of Songun 2010 |

| Cuschieri 1996 | Duplicate of Cuschieri 1999 |

| Degiuli 2010 | Dupicate of Degiuli 2014 |

| Dent 1988 | No survival data reported |

| Galizia 2015 | The authors compared the D2 lymphadenectomy with a modified (less extended) D2 lymphadenectomy, which made this RCT ineligible |

| Hartgrink 2004 | Duplicate of Songun 2010 |

| Kulig 2007 | No survival data reported |

| Onate‐Ocana 2000 | Non a randomized comparison |

| Sano 2004 | Duplicate of Sasako 2008 |

| Viste 1994 | Non a randomized comparison |

| Volpe 2000 | Non a randomized comparison |

| Wu 2004 | Duplicate of Wu 2006 |

Differences between protocol and review

The title has been changed (the previous review covered only D1 and D2 type lymphadenectomy, whereas the current version covers also D3 type lymph node dissection). Only RCTs are considered in the updated version of the review.

Contributions of authors

Peter McCulloch, Marcelo Eidi Nita, Hussain Kazi, Joaquin Gama‐Rodrigues: authors of the previous version.

Simone Mocellin, Yuhong Yuan, Donato Nitti: authors of the updated version.

Sources of support

Internal sources

University of Padova, Italy.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

SM: none known.

PMcC: none known.

HK: none known.

JJGR: none known.

YY: none known.

DN: none known.

New search for studies and content updated (conclusions changed)

References

References to studies included in this review

Cuschieri 1999 {published data only}

- Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, et al. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long‐term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. British Journal of Cancer 1999;79:1522‐30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Degiuli 2014 {published data only}

- Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A, Vendrame A, Tomatis M, Mazza C, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing survival after D1 or D2 gastrectomy for gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2014;101:23‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maeta 1999 {published data only}

- Maeta M, Yamashiro H, Saito H, Katano K, Kondo A, Tsujitani S, et al. A prospective pilot study of extended (D3) and superextended para‐aortic lymphadenectomy (D4) in patients with T3 or T4 gastric cancer managed by total gastrectomy. Surgery 1999;125:325‐31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Robertson 1994 {published data only}

- Robertson CS, Chung SC, Woods SD, Griffin SM, Raimes SA, Lau JT, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing R1 subtotal gastrectomy with R3 total gastrectomy for antral cancer. Annals of Surgery 1994;220:176‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sasako 2008 {published data only}

- Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Kurokawa Y, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, et al. D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para‐aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2008;359:453‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Songun 2010 {published data only}

- Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15‐year follow‐up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncology 2010;11:439‐49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wu 2006 {published data only}

- Wu CW, Hsiung CA, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Chen JH, Li AF, et al. Nodal dissection for patients with gastric cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncology 2006;7:309‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Yonemura 2008 {published data only}

- Yonemura Y, Wu CC, Fukushima N, Honda I, Bandou E, Kawamura T, et al. Randomized clinical trial of D2 and extended paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric cancer. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008;13:132‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Bonenkamp 1992 {published data only}

- Bonenkamp JJ, Velde CJH, Sasako M, Hermans J. R2 compared with R1 resection for gastric cancer: morbidity and mortality in a prospective randomised trial. European Journal of Surgery 1992;158:413‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bonenkamp 1999 {published data only}

- Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, Velde CJ, Welvaart K, Songun I, et al. Extended lymph‐node dissection for gastric cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 1999;340:908‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bunt 1996 {published data only}

- Bunt AMG, Hermans J, Cornelis JH, Velde CJH, Sasako M, Hoefsloot FAM, et al. Lymph node retrieval in a randomised trial on Western‐type versus Japanese‐type surgery in gastric cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1996;14:2289‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cuschieri 1996 {published data only}

- Cuschieri A, Fayers P, Fielding J, Craven J, Bancewicz J, Joypaul V, et al. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. Lancet 1996;347:995‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Degiuli 2010 {published data only}

- Degiuli M, Sasako M, Ponti A, Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group. Morbidity and mortality in the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group randomized clinical trial of D1 versus D2 resection for gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2010;97:643‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dent 1988 {published data only}

- Dent DM, Madden MV, Price SK. Randomized comparison of R1 and R2 gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. British Journal of Surgery 1988;75:110‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Galizia 2015 {published data only}

- Galizia G, Lieto E, Vita F, Castellano P, Ferraraccio F, Zamboli A, et al. Modified versus standard D2 lymphadenectomy in total gastrectomy for nonjunctional gastric carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Surgery 2015;157:285‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hartgrink 2004 {published data only}

- Hartgrink HH, Velde CJ, Putter H, Bonenkamp JJ, Klein Kranenbarg E, Songun I, et al. Extended lymph node dissection for gastric cancer: who may benefit? Final results of the randomized Dutch gastric cancer group trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2004;22:2069‐77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kulig 2007 {published data only}

- Kulig J, Popiela T, Kolodziejczyk P, Sierzega M, Szczepanik A. Standard D2 versus extended D2 (D2+) lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer: an interim safety analysis of a multicenter, randomized, clinical trial. American Journal of Surgery 2007;193:10‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Onate‐Ocana 2000 {published data only}

- Onate Ocana MF, Aiello Crocofogilio V, Mondragon Sanchez R, Ruiz‐Molina JM. Survival benefit of D2 lymphadenectomy in patients with gastric carcinoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2000;7:210‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sano 2004 {published data only}

- Sano T, Sasako M, Yamamoto S, Nashimoto A, Kurita A, Hiratsuka M, et al. Gastric cancer surgery: morbidity and mortality results from a prospective randomized controlled trial comparing D2 and extended para‐aortic lymphadenectomy‐‐Japan Clinical Oncology Group study 9501. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2004;22:2767‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Viste 1994 {published data only}

- Viste A, Svanes K, Jannsen CW, Maartmann Moe H, Soreide O. Prognostic importance of radical lymphadenectomy in curative resections for gastric cancer. European Journal of Surgery 1994;160:497‐502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Volpe 2000 {published data only}

- Volpe CM, Driscoll DL, Douglass HO. Outcome of patients with proximal gastric cancer depends upon the extent of resection and the number of resected lymph nodes. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2000;7(2):139‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wu 2004 {published data only}

- Wu CW, Hsiung CA, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Shia LT, Whang‐Peng J. Randomized clinical trial of morbidity after D1 and D3 surgery for gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2004;91:283‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Akagi 2011

- Akagi T, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Lymph node metastasis of gastric cancer. Cancers 2011;3:2141‐59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Allum 2012

- Allum WH. Optimal surgery for gastric cancer: is more always better?. Recent Results in Cancer Research 2012;196:215‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Altman 1999

- Altman DG, Andersen PK. Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. British Medical Journal 1999;319:1492‐5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arigami 2013

- Arigami T, Uenosono Y, Yanagita S, Nakajo A, Ishigami S, Okumura H, et al. Clinical significance of lymph node micrometastasis in gastric cancer. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2013;20:515‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blum 2013

- Blum MA, Takashi T, Suzuki A, Ajani JA. Management of localized gastric cancer. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013;107:265‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brar 2012

- Brar SS, Seevaratnam R, Cardoso R, Law C, Helyer L, Coburn N. A systematic review of spleen and pancreas preservation in extended lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2012;15(Suppl 1):S89‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cuschieri 2014

- Cuschieri SA, Hanna GB. Meta‐analysis of D1 versus D2 gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma: let us move on to another era. Annals of Surgery 2014;259:e90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal 1997;315:629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

El‐Sedfy 2014

- El‐Sedfy A, Dixon M, Seevaratnam R, Bocicariu A, Cardoso R, Mahar A, et al. Personalized surgery for gastric adenocarcinoma: a meta‐analysis of D1 versus D2 lymphadenectomy. Annals of Surgical Oncology 2014;22:1820‐7. [DOI: 10.1245/s10434-014-4168-6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ferlay 2014

- Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer 2014;136:E359‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Giuliani 2014

- Giuliani A, Miccini M, Basso L. Extent of lymphadenectomy and perioperative therapies:two open issues in gastric cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2014;20:3889‐904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Guyatt 2011

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2011;64:380‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hartgrink 2009

- Hartgrink HH, Jansen EP, Grieken NC, Velde CJ. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2009;374:477‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. British Medical Journal 2003;327:557‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Jansen 2012

- Jansen EP, Boot H, Velde CJ, Sandick J, Cats A, Verheij M. Can adjuvant chemoradiotherapy replace extended lymph node dissection in gastric cancer?. Recent Results in Cancer Research 2012;196:229‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jiang 2013

- Jiang L, Yang KH, Guan QL, Zhao P, Chen Y, Tian JH. Survival and recurrence free benefits with different lymphadenectomy for resectable gastric cancer: a meta analysis. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2013;107:807‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jiang 2014

- Jiang L, Yang KH, Chen Y, Guan QL, Zhao P, Tian JH. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effectiveness and safety of extended lymphadenectomy inpatients with resectable gastric cancer. British Journal of Surgery 2014;101:595‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Liberati 2009

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. British Medical Journal 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Memon 2011

- Memon MA, Subramanya MS, Khan S, Hossain MB, Osland E, Memon B. Metaanalysis of D1 versus D2 gastrectomy for gastric adenocarcinoma. Annals of Surgery 2011;253:900‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Parmar 1998

- Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta‐analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Statistics in Medicine 1998;17:2815–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]