Abstract

Background

People who are prescribed self administered medications typically take only about half their prescribed doses. Efforts to assist patients with adherence to medications might improve the benefits of prescribed medications.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to assess the effects of interventions intended to enhance patient adherence to prescribed medications for medical conditions, on both medication adherence and clinical outcomes.

Search methods

We updated searches of The Cochrane Library, including CENTRAL (via http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/cochranelibrary/search/), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO (all via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCO), and Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest) on 11 January 2013 with no language restriction. We also reviewed bibliographies in articles on patient adherence, and contacted authors of relevant original and review articles.

Selection criteria

We included unconfounded RCTs of interventions to improve adherence with prescribed medications, measuring both medication adherence and clinical outcome, with at least 80% follow‐up of each group studied and, for long‐term treatments, at least six months follow‐up for studies with positive findings at earlier time points.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted all data and a third author resolved disagreements. The studies differed widely according to medical condition, patient population, intervention, measures of adherence, and clinical outcomes. Pooling results according to one of these characteristics still leaves highly heterogeneous groups, and we could not justify meta‐analysis. Instead, we conducted a qualitative analysis with a focus on the RCTs with the lowest risk of bias for study design and the primary clinical outcome.

Main results

The present update included 109 new RCTs published since the previous update in January 2007, bringing the total number of RCTs to 182; we found five RCTs from the previous update to be ineligible and excluded them. Studies were heterogeneous for patients, medical problems, treatment regimens, adherence interventions, and adherence and clinical outcome measurements, and most had high risk of bias. The main changes in comparison with the previous update include that we now: 1) report a lack of convincing evidence also specifically among the studies with the lowest risk of bias; 2) do not try to classify studies according to intervention type any more, due to the large heterogeneity; 3) make our database available for collaboration on sub‐analyses, in acknowledgement of the need to make collective advancement in this difficult field of research. Of all 182 RCTs, 17 had the lowest risk of bias for study design features and their primary clinical outcome, 11 from the present update and six from the previous update. The RCTs at lowest risk of bias generally involved complex interventions with multiple components, trying to overcome barriers to adherence by means of tailored ongoing support from allied health professionals such as pharmacists, who often delivered intense education, counseling (including motivational interviewing or cognitive behavioral therapy by professionals) or daily treatment support (or both), and sometimes additional support from family or peers. Only five of these RCTs reported improvements in both adherence and clinical outcomes, and no common intervention characteristics were apparent. Even the most effective interventions did not lead to large improvements in adherence or clinical outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Across the body of evidence, effects were inconsistent from study to study, and only a minority of lowest risk of bias RCTs improved both adherence and clinical outcomes. Current methods of improving medication adherence for chronic health problems are mostly complex and not very effective, so that the full benefits of treatment cannot be realized. The research in this field needs advances, including improved design of feasible long‐term interventions, objective adherence measures, and sufficient study power to detect improvements in patient‐important clinical outcomes. By making our comprehensive database available for sharing we hope to contribute to achieving these advances.

Plain language summary

Ways to help people follow prescribed medicines

Background

Patients who are prescribed medicines take only about half of their doses and many stop treatment entirely. Assisting patients to adhere better to medicines could improve their health, and many studies have tested ways to achieve this.

Question

We updated our review from 2007 to answer the question: What are the findings of high‐quality studies that tested ways to assist patients with adhering to their medicines?

Search strategy

We retrieved studies published until 11 January 2013. To find relevant studies we searched six online databases and references in other reviews, and we contacted authors of relevant studies and reviews.

Selection criteria

We selected studies reporting a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing a group receiving an intervention to improve medicine adherence with a group not receiving the intervention. We included trials if they measured both medicine adherence and a clinical outcome (e.g. blood pressure), with at least 80% of patients studied until the end.

Main results

The studies differed widely regarding included patients, treatments, adherence intervention types, medicine adherence measurement, and clinical outcomes. Therefore, we could not combine the results in statistical analysis to reach general conclusions, as it would be misleading to suggest that they are comparable. Instead, we provide the key features and findings of each study in tables, and we describe intervention effects in studies of the highest quality. The present update included 109 new studies, bringing the total number to 182. In the 17 studies of the highest quality, interventions were generally complex with several different ways to try to improve medicine adherence. These frequently included enhanced support from family, peers, or allied health professionals such as pharmacists, who often delivered education, counseling, or daily treatment support. Only five of these RCTs improved both medicine adherence and clinical outcomes, and no common characteristics for their success could be identified. Overall, even the most effective interventions did not lead to large improvements.

Authors' conclusions

Characteristics and effects of interventions to improve medicine adherence varied among studies. It is uncertain how medicine adherence can consistently be improved so that the full health benefits of medicines can be realized. We need more advanced methods for researching ways to improve medicine adherence, including better interventions, better ways of measuring adherence, and studies that include sufficient patients to draw conclusions on clinically important effects.

Background

Description of the condition

Low patient adherence is a major barrier to realizing the benefits of medications that have been shown to do more good than harm in clinical trials. Such trials are typically done among patients who are volunteers, and who are followed closely to assure high adherence. Benefits are greatly reduced or nullified in usual clinical practice where adherence rates are low. Interventions to improve adherence have the potential to multiply benefits for patients, but at the time of our previous review, Haynes 2008, no method of helping patients to follow self administered long‐term treatments had been proven effective, actionable, and affordable in usual care settings.

Many patients stop taking their medication in the first months following initiation, often without informing their provider, with further attrition over time. In addition, many patients who continue their medication do not consistently take it as prescribed. As a result, adherence rates average around 50% and range from 0% to over 100%, and there is no evidence for substantial change in the past 50 years (Sackett 1979; Gialamas 2009; Naderi 2012).

Medication non‐adherence is often defined as taking less than 80% of prescribed doses, although it has to be noted that non‐adherence can also include taking too many doses, and it is associated with an increased risk for poor health, adverse clinical events, and mortality. Thus many people who could benefit from medications do not, and much of the public and private investment in health research and health care is undermined. To make matters worse, low adherence, even to placebo, is independently associated with an increased risk of death ('healthy adherer' effect) (Simpson 2006). Therefore, enhancing medication adherence is a priority and could improve patient outcomes, primarily through the effect of medications, but also possibly through the overall 'healthy adherer' effect.

Description of the intervention

Our most recent update (search until January 2007) of this Cochrane review included 78 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that had ≥ 80% follow‐up and tested the effect of adherence interventions on both adherence and clinical outcomes (Haynes 2008). We believe it is essential to have measures of both adherence and clinical outcomes, as ethical standards for adherence research dictate that attempts to improve adherence should be judged by their clinical benefits (NHLBI 1982). Studies that measure only adherence cannot show that patients are better off as a result, and studies that measure only clinical outcomes cannot verify that effects on adherence were important to achieving these outcomes.

Further, we described findings across disease conditions, as the clinical condition is not a major determinant of medication adherence, with the exception of psychiatric disorders (Haynes 1979a). Do note that studies targeting adherence for medications to treat psychiatric disorders are included in our review.

Our 2008 update found, besides the expected variety in medical conditions and regimens, a large diversity and complexity of interventions and of measures for adherence and patient outcomes (Haynes 2008). Although some intervention types tended to improve adherence, no specific recommendations could be given, especially since high‐quality evidence for consistent effects on both adherence and patient outcomes was lacking.

Why it is important to do this review

With increasing numbers of efficacious self administered treatments being available, the need for effective interventions to improve adherence is ever more apparent. In recent years, research efforts to better understand the multifactorial barriers that influence patient adherence and to refine theoretical frameworks have been increasing. However, whether these efforts have led to the emergence of more effective interventions needs to be assessed by summarizing the high‐quality RCT evidence to date. Many systematic reviews have been published after our 2008 update, but all focused on a specific (demographic, disease, or medication) population, intervention, or on an even more specific combination of both. Generally, these reviews reported similar conclusions: some intervention components are potentially effective, but small sample sizes and suboptimal methodology often prevented strong conclusions; the variety of adherence measures limited study comparability; and most studies lacked a theoretical underpinning (van Dulmen 2007).

Considering the substantial efforts in adherence research since 2007, and inconclusive evidence from other recent systematic reviews, we have updated our comprehensive systematic review. Based on publication rates over time in the previous review update, we predicted that we would find at least 50 additional RCTs, and thereby potentially improve our confidence for specific conclusions and recommendations.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to assess the effects of interventions intended to enhance patient adherence to prescribed medications for medical conditions, on both medication adherence and clinical outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

This systematic review is an update of the review by Haynes et al (Haynes 2008), which searched for studies until February 2007. As of 24 November 2013, no other comprehensive adherence reviews were registered in the Cochrane Database or PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/). We used a web‐based database management system, developed by the Health Information Research Unit at McMaster University, to facilitate screening, data extraction, adjudication of disagreements, author review and confirmation of data, production of data tables, and production of data files for future research use. This system has been successfully used in conducting and completing several large, complex systematic reviews (Haynes 2010).

Studies for this review were included if they were RCTs that provided unconfounded tests of interventions expected to affect adherence. A confounder is a characteristic that is extraneous to the primary question being addressed in the study, but which can influence the outcome and is unequally distributed between the groups being compared in the trial. For example, in one study (Colcher 1972), two groups received the same prescription for phenoxymethyl penicillin, but different instructions, providing an unconfounded comparison for the instructions, but a third group in the same trial received a different drug (penicillin G benzathine) by a different route (intramuscularly) with a different dose (1.2 million units) and schedule (one dose), making it impossible to separate out independent adherence effects of this regimen. Thus, only the unconfounded comparison of instructions for phenoxymethyl penicillin was included in the review.

Types of participants

Patients who were prescribed medication for a medical (including psychiatric) disorder, but not for addictions (as these adherence problems are typically of a different nature and much more severe).

Types of interventions

Interventions of any sort intended to affect adherence with prescribed, self administered medications.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies if they reported at least one medication adherence measure and at least one clinical outcome. Regarding follow‐up completion, studies needed to have at least 80% follow‐up at the end of the recommended treatment period for short‐term treatments, and at least 80% follow‐up during at least six months for long‐term treatments with initially positive results. For long‐term regimens, we included negative trials with less than six months follow‐up and at least 80% data completion on the grounds that initial failure is unlikely to be followed by success (Sackett 1979). The 80% data completion was required for both adherence and clinical outcomes, and for any outcome other than mortality, the denominator for determining data completion excluded those patients who died before the outcome assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched: The Cochrane Library including CENTRAL (via http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/cochranelibrary/search/), MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO (all via Ovid), CINAHL (via EBSCO), and Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest). We completed database searches for relevant articles on 11 January 2013, updating previous searches that were undertaken on: 1 September 1993; 12 December 1993; 1 June 1994; 30 June 1995; 28 February 1997; 31 July 1998; 15 August 2001; 30 September 2004; and 1 February 2007. We searched new publications since 1 January 2007, that is, having a one‐month overlap with the previous search. All databases were originally searched from their start date.

The search filters for each database, and from the current and previous update, are shown in Appendix 1. We checked articles cited in reviews and original studies of patient adherence. We contacted authors of included RCTs to identify additional studies.

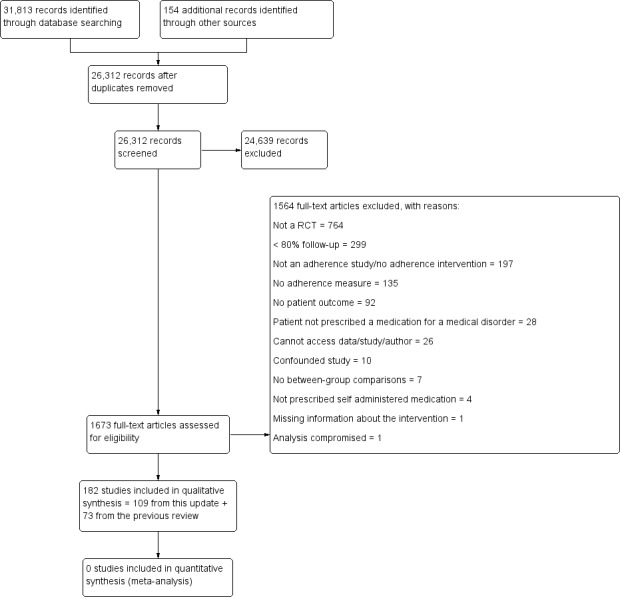

We re‐assessed all RCTs included in the 2008 update for eligibility to carry over into the current update. Retrieved citations from the updated search entered a first screening stage. Based on the title and abstract, studies moved to the second screening stage if they met all five eligibility criteria or if there was uncertainty about their eligibility. In the second screening stage, assessment of the full text determined if studies were included in the review. At both screening stages, two independent review authors assessed eligibility, and an adjudicator resolved disagreements. We recorded reasons for excluding citations in the second screening stage. The PRISMA flow chart showing the results for selection of papers is provided in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data collection and analysis

We imported data from the 2008 review into the update database, and checked the data for accuracy. Extracted data included items as provided in the tables from the previous Cochrane review (Haynes 2008): the 'Characteristics of included studies' table (i.e. methods, participants, interventions, outcomes, additional notes pertaining to any one of the aforementioned items, detailed assessment of risk of bias), and the 'Adherence and outcome' table (i.e. clinical problem, intervention, control, effect on adherence outcome, effect on clinical outcome). We extracted the same items for new included studies. In addition, we extracted items from the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool for all included studies from the previous and current update (Higgins 2011). Two review authors independently extracted all new data, and an adjudicator resolved disagreements. We contacted primary or corresponding authors of all included RCTs to confirm extracted data and provide missing data.

We quantified review author agreement on study 'Risk of bias' criteria using the unweighted Cohen's kappa (k) coefficient (Fleiss 1981). We carried out all analyses using SPSS, version 20.0. When reporting results from individual studies, we cited the measures of association and P values reported in the studies. We interpreted P value < 0.05 as indicating statistical significance. Due to the extreme heterogeneity in clinical conditions, participant selection criteria, medical regimens, interventions, adherence measures, and clinical outcome measures, pooling results according to any of these characteristics would still leave highly heterogeneous groups. In support of this, we refer to the meta‐analysis reported by the Ascertaining Barriers for Compliance (ABC) project team, which exclusively focused on RCTs that measured adherence by means of electronic medication event monitoring systems (MEMS) and still found a very high heterogeneity of effects (I2 = 98.88%) (ABC Project Team 2012). Pooling of effects in our review was further undermined by the frequent use of complex interventions, which was already problematic for categorizing intervention types in the previous update. Studies also had very heterogeneous clinical outcomes; they also often lacked clearly defined primary outcomes. We could not justify even plotting intervention effects without pooling in meta‐analysis, as this would imply some degree of comparability among the studies. Rather, as a best case alternative, we conducted a narrative analysis of the studies with the lowest risk of bias, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011), for study design (random sequence generation and concealment of allocation), and for their primary clinical outcome (blinding of outcome assessor, as relevant for the outcome in question). We did not require low risk of bias for the primary adherence measure, as this would have resulted in discussion of very few studies, as most adherence measures have a high or uncertain risk of bias, notably because of lack of blinding.

We reported intervention effects in individual RCTs for all outcomes for a) adherence and b) clinical outcomes. We reported effects in the RCTs identified as low risk of bias as described by the authors, with a focus on the primary outcomes, and with comments on methodological issues that might have influenced results, such as absence of correction for multiple comparisons. We considered adherence and clinical outcomes to be the primary outcome if they were:

indicated to be the primary outcome by the study author; OR

used in the study power calculation; OR

the first outcome described in the 'Results' section of the article.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The new search identified 26,312 citations of which we assessed 1673 in full text. Of these, we included 109, based on a full‐text review in the second screening phase. The PRISMA flow chart shows the results for selection of papers and is provided in Figure 1.

Included studies

The previous update included 78 RCTs, of which 73 were carried over into the current update. We excluded five previously included RCTs: in the course of this review update, we identified that two did not address self administered medication (Canto De Cetina 2001; Ran 2003), one had less than 80% follow‐up (Van Servellen 2005), one reported no data for clinical outcome (van Es 2001), and one was confounded (Piette 2001). Therefore, we included a total of 182 RCTs in the current update. The overall number of RCT participants was 46,962. However, this overall number does not reflect the strength of the evidence base, considering that we could not meaningfully combine results of included studies. The newly added studies represent a growth in the knowledge base of 150% in the past six years, with more than twice the number of trials than we had predicted based on publication rates in the 2008 review.

Key features of all 182 RCTs are summarized in the table Characteristics of included studies. The most frequently targeted conditions in all RCTs were:

HIV/AIDS (36);

psychiatric disorders (29);

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (27);

cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk (21);

hypertension (17); and

diabetes (16).

The remaining studies targeted:

dyslipidemia (6);

antibiotics (4);

arthritis (3);

complex chronic care (3);

dyspepsia (3);

glaucoma (2);

oral anticoagulation (2);

osteoporosis (2);

tuberculosis (2);

acne (1);

cancer (1);

hepatitis (1);

iron supplementation during pregnancy (1);

liver transplant (1);

malaria (1);

oral contraceptives (1);

tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy (1); and

ulcerative colitis (1).

Among the 109 new RCTs, 80 were from high‐income countries (44 from USA), 17 from middle‐income countries, five from low‐income countries, and seven from unknown geographic locations (World Bank classification, http://data.worldbank.org/about/country‐classifications/country‐and‐lending‐groups). In a majority of new RCTs (67) the adherence intervention targeted more than one medication, while 27 targeted one medication (the number of medications was unknown for the remaining 15 RCTs).

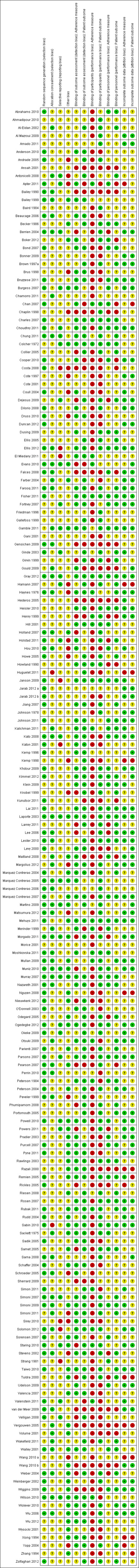

There were substantive differences across studies in settings, clinical disorders, treatment regimens, adherence interventions, adherence measures, and clinical outcome measures, so that there was insufficient common ground for quantifying differences between groups or estimating pooled effect sizes that would permit meaningful quantitative analysis of findings across studies. Instead, we indicated which differences were statistically significant for adherence or clinical outcomes between the groups compared in each RCT (see Analysis 1.1). Of note, some of the negative results were unconvincing because of low statistical power: 44 RCTs did not meet the minimal required sample size of 60 patients per treatment group to detect an absolute difference of 25% in adherence with 80% power (Haynes 2008).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Studies that met criteria, Outcome 1 Adherence and outcome.

| Adherence and outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Clinical problem | Intervention | Control |

Effect on adherence (Yes means a statistically significant effect in favor of the intervention; No means no effect or a negative effect) |

Effect on clinical outcome (Yes means a statistically significant effect in favor of the intervention; No means no effect or a negative effect) |

| Abrahams 2010 | Post‐exposure prophylaxis for HIV | TELEPHONE COUNSELING: Patients in the intervention group received standard care and telephone counseling sessions. The telephone counseling included 4 calls in the first week, 3 calls in the second and third week, and 2 calls in the last week, but more were made if necessary. The support included the application of basic counseling skills including listening and validating the traumatic events, encouraging participants to take their medication, to seek support from family and friends, to attend formal counseling services, to read the pamphlet, use the diary, and return to the clinic for follow‐up medication (n = 136) | STANDARD CARE: Standard care consisted of psychological containment, medical examination and collection of forensic evidence; HIV testing with pre‐ and post‐test counseling; providing emergency contraception, treatment of sexually transmitted infections and PEP for HIV. Follow‐up was arranged to collect further HIV PEP medication. All patients had an interactive information session to explain the content of the pamphlet, answer questions and demonstrate initiation of the use of the medication diary. The pamphlet contained specific information about taking PEP after a sexual assault; a diary for the 28‐day period on which pill taking was to be marked and contact information on support services. No further contact was made with participants in the control group until the final interview, but they continued to receive standard care from the service (n = 138) | No for improving adherence to prophylactic HIV treatment | No for depressive symptoms |

| Ahmadipour 2010 | Type 2 diabetes | DIARY CHECKLIST: The intervention group was asked to complete a diary checklist about how they took their drugs during the study period.The duration was 12 weeks (n = 50) | COLLECTION OF MEDICATION SHELLS: The control group patients were asked to collect the shells of oral hypoglycemic agents after taking in a pocket. Duration was 12 weeks. (n = 50) | Yes for improving medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes with a diary check list intervention | No for improvement in HbA1c levels |

| Al Mazroui 2009 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | PHARMACIST CARE INTERVENTION: For all patients randomized to the intervention group, the research pharmacist had discussions with their physicians regarding drug therapy and, if necessary, treatment modification was recommended, e.g. more intensive management of hypertension or simplification of dosage regimens if deemed appropriate, taking account of the latest American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommendations. Patients who were randomized to the intervention group were educated on their illness and their medication in a structured fashion, including discussion on risk of diabetes complications, proper dosage, side effects and storage of medications, healthy lifestyle and management of diabetes mellitus signs and symptoms through self monitoring. A printed leaflet to assist with the education program was developed and the patient was given a copy to take home. Supplementary leaflets containing information about hypertension and hyperlipidemia were also given to the patients if they suffered from these conditions. The educational advice was reinforced when patients came to the hospital pharmacy to collect their prescribed medicines on their monthly schedule. In addition, behavioral modification aspects of the Pharmacist Care intervention involved advice on the following: self monitoring of glycemic control (patients were encouraged to monitor their blood glucose levels 3 times per day, to record these values and bring a record book to all subsequent appointments); physical exercise (this involved initiation of an exercise plan that could be incorporated into the patient’s daily schedule, after taking into consideration their level of fitness, e.g. 1‐hour walk daily; diet (the patient was assisted with the identification of dietary behavior that adversely influences blood glucose control, lipid levels, weight management, and of the times of day when the patient was most vulnerable to overeating, and given improved understanding of the relative effects of certain food choices on blood glucose control); medication adherence (patients were asked about any problems that they had encountered with regard to taking their medication and were offered education and practical help to encourage them to take the medicines prescribed for them by their physician); and smoking cessation (patients were encouraged to stop smoking by advising them about the danger of smoking to health, with emphasis on the increased dangers of smoking in diabetic patients) (n = 120) | USUAL CARE: Control group participants received normal care from medical and nursing staff. They did not receive any pharmacy clinical service but received advice on self monitoring their blood glucose by medical or nursing staff (n = 120) | Yes for improving adherence to medication at 12 months | Yes for BMI, blood glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, quality of life, Framingham prediction scores, and British National Formulary risk prediction |

| Al‐Eidan 2002 | Helicobacter pylori | Intervention patients (n = 38) received their medicines via the hospital pharmacy and were counseled (and followed up) by a hospital pharmacist | Control patients (n = 38) were given a standard advice sheet and referred to their GP who prescribed the same therapy | Yes for improving compliance with a 1‐week course of triple therapy to eradicate H. pylori | Yes for improving clinical outcomes for the intervention group who had a significantly higher rate of H. pylori eradication |

| Amado 2011 | Hypertension | INTERVENTION (IG): Patients in the Intervention Group (IG) had 4 visits with specially trained nurses who used standardized guidelines and who had attended a 10‐hour workshop that focused on the antihypertensive medications. Each visit lasted for an average of 15 minutes. Information was personalized to the needs of the patient. Schedule sheets with the treatment plan were provided which contained information on the prescribed drugs and dosage schedule as well as basic advice on how to maximize the treatment schedule. The sheets were provided to reinforce the nurse's verbal instructions (n = 515 ) | CONTROL GROUP (CG): Control patients received usual clinic care without any standardized intervention (n = 481 ) | Yes for Haynes‐Sackett test; no for Morisky‐Green test, self declared 3‐month adherence, and pill count | No for systolic and diastolic blood pressure, hypertension control, BMI, and number of antihypertensive drugs taken |

| Anderson 2010 | Schizophrenia | ADHERENCE TREATMENT: The intervention was 'Adherence Therapy' a manualized, patient‐centric approach that seeks to address a broad range of factors known to affect adherence. This individual therapy focuses on the needs, concerns, fears, values, goals, and experiences of the individual with the aim of encouraging people to take their medications. It was delivered by 4 therapists with Master's degree in social work. There were 8 one to one sessions of between 20 to 60 minutes, over 8 weeks. Follow‐up was conducted after the completion of the therapy. All intervention patients also received treatment as usual (n = 12) | TREATMENT AS USUAL: TAU included day treatment, case management, employment placement, medication monitoring, and individual counseling. During the trial, AT participants did not see their own therapist for therapy sessions, but continued their other treatment activities (n = 14) | No for improving adherence to antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia patients receiving adherence therapy and treatment as usual at 8 weeks | No for improving the PANSS positive, negative and general scores in schizophrenia patients receiving adherence therapy and treatment as usual at 8 weeks |

| Andrade 2005 | HIV | Disease Management Assistant System (DMAS) device, programmed with verbal reminder messages and dosing times for medications in the highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) regimen with monthly adherence counseling and feedback (see Control; n = 29) | Monthly adherence counseling (education about barriers to adherence, hazards of non‐adherence, their prescribed HAART regimen) and adherence feedback (n = 29) | No for all adherence outcomes | No for CD4+ cell count. Yes for plasma HIV RNA (significant for 2 of 4 measures) |

| Ansah 2001 | Malaria | The use of pre‐packed chloroquine tablets (n = 155) | The use of chloroquine syrup (n = 144) | Yes. The tablet form of medicine resulted in higher adherence rates, but it is not established whether this is due to the formulation or the lack of provision of a standard measuring device | No, there was no difference in the clinical outcomes |

| Antonicelli 2008 | Congestive heart failure | HOME TELEMONITORING: Patients were in a 12‐month follow‐up period. Patients (or one of their relatives) were contacted by telephone at least once a week by the CHF team to obtain information on symptoms and adherence to prescribed treatment, as well as blood pressure, heart rate, bodyweight and 24‐hour urine output data for the previous day. A weekly ECG transmission was also required. Evaluation of these parameters was followed by reassessment of the therapeutic regimen and modification whenever needed. In addition, clinic visits were arranged as required on the basis of the data provided by telemonitoring or telephone interviews. Decisions on hospital re‐admission during follow‐up in both groups were made after consultation with a CHF team member (n = 29) | STANDARD CARE: Patients (or one of their relatives) in the control group were contacted monthly for 12 months of follow‐up by telephone to obtain data on new hospital admissions, cardiovascular complications and death. These patients were also routinely seen in the CHF outpatient clinic every 4 months, with additional visits being arranged whenever changes in clinical status made this necessary (n = 28) | Yes for improving adherence to beta‐blockers, HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors and aldosterone receptor agonists at 12 months in elderly patients with CHF | Yes for composite endpoint of mortality and hospital readmission, hospital readmission (alone) and heart rate reduction. No for left ventricular ejection fraction change and mortality (alone) |

| Apter 2011 | Asthma | PROBLEM‐SOLVING INTERVENTION: Participants met with a research co‐ordinator for 4 sessions of a problem‐solving (PS)intervention. PS comprised 4 30‐minute sessions. The individualized intervention involved 4 interactive steps, usually 1 per research session. For the 158 participants who reported missing doses of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), the goal was to improve adherence. For the 7 participants who declared adherence to the prescribed regimen, the goal was to maintain adherence. The first PS step consisted of defining the problem: improving or preserving adherence to ICS use within the patient's unique context and orientation. Problem orientation facilitated the adoption of a rational, positive, and constructive appraisal of how to achieve adherence, with non‐adherence being presented as a problem to be solved. PS was presented as a means of coping with problems more generally and modifying attitudes or beliefs that inhibit or interfere with attempts to solve problems. It was a motivational technique to help the participant view the occurrence of problems as inevitable, normal, and solvable. This first step involved breaking problems into small achievable pieces. The second step was brainstorming for alternative solutions. The third step was choosing the best solution by weighing the consequences, both desirable and undesirable, of each candidate solution. Between the third and 4th meetings, the solution was tried. For the 4th step, the chosen solution was evaluated and revised. As part of this intervention, downloaded data from monitored ICSs were shared with the participant in a nonjudgmental fashion at each visit. At these sessions, subjects followed the same PS steps for addressing an additional problem of their own choosing, such as increasing physical activity. The problems were sometimes interrelated; for example, a father wants to play sports with his child, and improving asthma management makes this easier (n = 165) | ASTHMA EDUCATION: Patients attended 4 30‐minute sessions, conducted by a research co‐ordinator. Each session was about an asthma education (AE) topic unrelated to self management, adherence, or inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy. The topics covered, 1 at each session, were the following: (1) the proper technique for using an albuterol rescue metered‐dose inhaler and a dry powder inhaler or spacer, depending on the patient's medications; (2) the use of peak flow meters; (3) common asthma triggers; and (4) the pathophysiology of asthma. These sessions did not involve discussion of problem‐solving or adherence, only didactic presentation of health information (n = 168) | No for improvement in medication adherence | No for improving asthma control, spirometry, emergency department visits and hospitalizations, and asthma‐related quality of life |

| Bailey 1990 | Asthma | Pamphlet, workbook, counseling, phone follow‐up, support group, and reinforcement of adherence (n = 132) | Instructional pamphlet alone (n = 135) | Yes | Yes |

| Bailey 1999 | Asthma | 2 intervention groups: 1) Asthma Self Management Program (n = 78) ‐ a skill‐oriented self help workbook, which patients were counseled about in a one‐on‐one session and during 2 asthma support group meetings. Patients were also given peak flow meters and trained to use them for early detection of impending asthma attacks. They also received 2 telephone calls and a follow‐up letter at 1, 2, and 4 weeks, after the counseling session. 2) Core‐Elements Program (n = 76) ‐ a revised, shortened workbook that was reviewed in a 15 to 20 minutes one‐to‐one counseling session. Patients were trained to use inhalers and peak flow meters. They also received a follow‐up telephone counseling session a week later and a follow‐up letter 2 weeks later | Usual education from their physician, as well as a standardized set of pamphlets containing information about asthma. No steps were taken to ensure that patients read the pamphlets (n = 78) | No (medication adherence and inhaler use) | No for all clinical outcomes (asthma symptoms, respiratory illness, functional impairment, use of health services |

| Baird 1984 | Hypertension | Once daily metoprolol (n = 196) | Twice daily metoprolol (n = 193) | Yes | No |

| Beaucage 2006 | Acute infections | Pharmacist telephone follow‐up intervention (PTFI; n = 126) | Usual pharmacist intervention (UPI; n = 129) | No | No for all clinical outcomes |

| Becker 1986 | Hypertension | Special "reminder" pill packaging (n = 86) | Separate vials for each medication (n = 85) | No | No |

| Berrien 2004 | HIV | The intervention in intervention group (n = 20) consisted of 8 structured home visits over a 3‐month period by the same home care experienced registered nurse. The visits were designed to improve knowledge and understanding of HIV infection, to identify and resolve real and potential barriers to medication adherence, and ultimately to improve adherence. Spanish‐speaking case managers, incentives, notebooks with stickers and pill‐swallowing training were also part of the home visit training sessions | In the clinic setting for control group (n = 17), the physician, nurse and social worker provided standard medication adherence education at clinic appointments generally scheduled at 3‐month intervals. Phone follow‐ups and a single home visit were planned if the staff felt they were needed. Visual aids for remembering medications, medication boxes, beepers, and general technical and emotional support were regularly offered. The clinic nurse contacted the family by telephone when the patient was starting a new medication, was having difficulty with adherence, or needed clarification and support. A single home visit was planned when and if the clinic staff believed medication adherence was poor despite the implementation of the above listed techniques | Yes for pharmacy report of refill frequency; no for self reported | No |

| Boker 2012 | Mild to moderate acne | TEXT MESSAGE REMINDERS: 20 patients were then randomized to receive daily, customized text‐message reminders at a predetermined time. The website LetterMeLater.com was used to create an automated and customized electronic reminder schedule for each patient in this group at their baseline visit. Individual texting schedules were chosen based on each patient's preference and the anticipated time of each medication use. Once the schedule was created, patients in the reminder group received a customized text message twice daily (morning and evening), reminding them to apply the Duac (Stiefel Laboratories) or Differin (Galderma) gels, respectively. The content of each text message was identical for each patient and varied only by including the recipient's first name at the start of the message. Patients in the reminder group were asked to text back a reply if and when each application was completed in an attempt to compare actual adherence (measured by MEMS caps opening/closing events) and self reported adherence. All medication tubes and their corresponding MEMS caps were clearly labeled to avoid mix‐ups (n = 20) | USUAL CARE: Control group patients received usual care and were not provided with text message reminders. (n = 20) | No for improving adherence to acne medication with daily, customized text messages | No for improvement in acne severity or quality of life with text messages |

| Bond 2007 | Coronary heart disease | MEDICINE MANAGEMENT SERVICE (MEDMAN): The intervention was a comprehensive, community pharmacy‐led medicines management called MEDMAN. This intervention comprised of an initial consultation with a community pharmacist to review the appropriateness of therapy, compliance, lifestyle, social and support issues. Further consultations were provided according to pharmacist‐determined patient need. Recommendations were recorded on a referral form which was sent to the GP, who returned annotated copies to the pharmacists. The intervention lasted 12 months (n = 980) | STANDARD CARE: Control group patients not provided with MEDMAN intervention. Follow‐up data were collected at 12 months by audit clerks and postal questionnaire as at baseline. Intervention patients were also asked about their experience of the medicine management service (n = 513) | No for improving medication compliance in patients with coronary heart disease with a medicines management service | No statistically significant differences were found for any of the (adjusted) main outcome measures between the 2 groups at follow‐up |

| Bonner 2009 | Asthma | INDIVIDUALIZED ASTHMA MANAGEMENT INTERVENTION: Families in the intervention group received asthma education by a trained Family Co‐ordinator who also provided individualized support in helping caregivers monitor their children's asthma using diaries. The Family Co‐ordinator helped caregivers interpret the diaries and communicate the contents to their doctors. 3 group education workshops were held at 1‐month intervals that followed the asthma self regulation model. Families were trained to use the diaries and peak flow meters. Family Co‐ordinators regularly called families to discuss their diary records. The second workshop used patients' diary records as illustrations of the relative effectiveness of controller medicines over rescue/quick‐relief drugs in preventing asthma symptoms over time. Participants reviewed their own records of medicines and symptoms. The third workshop described asthma management as a two‐pronged effort of pharmacotherapy and trigger control. Between the 1st and 2nd workshops, the Family Co‐ordinator prepared families for their doctor visit. The Family Co‐ordinator accompanied families to the doctor visit where he intervened if the family failed to communicate a thorough asthma history. The children in the intervention group were tested for allergies by an attending allergist at the hospital if they had not recently been tested by their own physician. Family Co‐ordinator conducted a home environment assessment and suggested strategies for reducing asthma triggers (n = 56) | USUAL CARE: Control patients (n = 63) received usual medical care at private or hospital‐affiliated community pediatric practice (n = 63) | Yes for family adherence to asthma medicines according to the frequency and dosage as prescribed on the labels and yes for prophylactic use of bronchodilators | Yes for improvements in self efficacy for management of asthma, phase of asthma regulation and symptom persistence |

| Brown 1997a | Hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease | Controlled release niacin twice daily (n = 31) | Regular niacin 4 times a day (n = 31) | Yes | Yes |

| Brus 1998 | Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | 6 patient education meetings. The education program focused on compliance with sulphasalazine therapy, physical exercises, endurance activities (walking, swimming, bicycling), advice on energy conservation, and joint protection. 4 (2‐hour) meetings were offered during the first months. Reinforcement meetings were given after 4 and 8 months. The program was implemented in groups and partners were invited to attend the meetings (n = 29) | The control group received a brochure on RA, as provided by the Dutch League against Rheumatism. This brochure gives comprehensive information on medication, physical and occupational therapy (n = 31) | No | No |

| Bruzzese 2011 | Moderate to severe persistent asthma | ASTHMA SELF MANAGEMENT FOR ADOLESCENTS (ASMA): Students in the ASMA group receive an 8‐week intensive program. The intervention consists of 3 45‐ to 60‐minute group sessions, and individual tailored coaching sessions held at least once per week for 5 weeks. Sessions are delivered by trained health educators during the school day. In addition to teaching asthma management skills and ways to cope with asthma, the health educators encourage students to see their medical provider for a clinical evaluation and treatment. The individual sessions reinforce the educational messages taught in the group, help students identify and overcome barriers to managing their asthma, and coach students regarding their medical visits. The health educator offers to accompany the student to the medical visit to provide moral support, coaching, or advocacy when coaching fails. Medical providers received a presentation by experts in person or by telephone about a recommended change in therapy. The medical providers were first mailed a packet containing: a letter informing them that one of their patients was in the study and would be referred to him/her for a clinical evaluation; a blank asthma checklist the students complete throughout the intervention and bring to the visit with the provider; and a blank asthma action plan the provider is asked to complete. Within 2 weeks, a pediatric pulmonologist or adolescent medicine specialist called the students' medical providers to discuss the concepts presented in the program and to answer any questions regarding NHLBI Institute criteria for treating asthma (n = 175) | WAIT LIST CONTROL: The control group were kept on wait list until the completion of 12‐month interviews and then received the ASMA intervention (n = 170) | Yes for improving adherence in adolescents with asthma at 6 months; No for improving adherence in adolescents at 12 months | Yes for reducing night‐time awakenings in previous 2 weeks, and school absence in previous 2 weeks. No for reducing symptom days in prior 2 weeks. No for improving QOL at 6 months. Yes for QOL improvement at 12 months. Yes for reduction in urgent medical care use |

| Burgess 2007 | Asthma | FUNHALER: Patients received a Funhaler for their daily asthma medication. The Funhaler is a small volume spacer that incorporates an incentive toy (spinning disk and whistle) that is driven by the child's expired breath (n = 26) | CONTROL SPACER: Patients received a standard spacer for administering asthma medication (n = 21) | No for improving adherence to medication at 3 months in asthma patients | No for exacerbations of asthma. No for reducing the frequency of wheeze or cough at 3 months |

| Chamorro 2011 | Hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOLLOW‐UP: The intervention consisted in follow‐up of the patients by the pharmacist. He gave written and oral information about cardiovascular prevention and adherence to the patients in the first interview. The pharmacist adopted a pharmacotherapy follow‐up program, for 4 visits over 16 to 18 weeks. The final assessment was at 32 weeks (n = 44) | EDUCATION: This procedure consisted of health education, written and oral material all given in 1 session at enrollment (n = 41) | No for adherence at 8 months | No for all clinical health outcomes |

| Chan 2007 | Persistent asthma | INTERNET‐BASED HOME MONITORING AND EDUCATION: Both groups had 6 visits scheduled at 0, 2, 6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks, with the study pediatrician and 1 of the 4 assigned nurse case managers or the pediatric clinical pharmacist case manager. The intervention group received 3 in‐person visits, at 0, 26, and 52 weeks, and the rest as virtual visits. Virtual visits included asthma education, a video recording of peak flow meter and inhaler use forwarded to the website, daily asthma diaries, and communication with the case manager electronically via the website. Patients were provided a home computer system, camera, and Internet access. On‐site in‐home instruction was provided by technical experts on equipment use and website capabilities and use. Each patient received the same models of computer and computer equipment, as well as broadband Internet access. Patients and their parents were taught how to use the equipment and how to record and to submit videos by using a computer‐mounted digital video camera, to capture the patient's peak flow meter and inhaler technique. A detailed asthma symptom diary and quality of life survey were included on the website. Patients and families were instructed regarding the submission of daily symptom diary entries. Videos were recorded and loaded on the site for the case manager, who scored them with standardized checklists and provided instruction through e‐mail back to the patient/family. Videos were sent 2 times per week for 6 weeks and then once‐weekly thereafter. Moreover, patients received the following same service as the control group: they were contacted (by e‐mail) by the case manager 2 times per week for 6 weeks and once per week thereafter, to review the asthma action and home management plans, to assess the symptom diary, to remind the patient to perform and to record peak flow measurements daily in the diary, to remind the patient to complete symptom diary information every day, to answer questions, and to intervene if needed. All patients were able to contact the case manager 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (n = 60) | OFFICE‐BASED VISITS: Patients were treated with an ambulatory asthma clinical pathway, with 6 visits scheduled 0, 2, 6, 12, 26, and 52 weeks after enrollment. At each visit, patients and their parents received in‐depth asthma education from the case manager, with specific subjects being determined by an asthma educational pathway. Office‐based group patients received all of their information in person at the pediatric clinic. Patients were able to contact their case manager by telephone (n = 60) | No for improving asthma controller medication adherence with internet‐based patient education and home monitoring for children with asthma | No for rescue medication use or emergency visits, symptoms, asthma knowledge and inhaler technique |

| Chaplin 1998 | Schizophrenia | Individual semi‐structured educational sessions discussing the benefits and adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, including tardive dyskinesia (n = 28) | Usual care (n = 28) | No | No |

| Charles 2007 | Asthma | AUDIOVISUAL REMINDER: The intervention was an audiovisual reminder attached to the inhaler. When the alarm was switched on, it generated a single beep, which sounded once every 30 seconds for 60 minutes after the predesignated time, which was programmed into the device. The alarm stopped if the MDI was actuated or after 60 minutes if not taken. The device was programmed to emit the alarm at predetermined times twice a day. The AVRF also had a colored light, which was green before MDI use, changing to red once the MDI was taken. This function served to remind patients whether they had taken the MDI as scheduled. Follow‐up period was 12 weeks (n = 55) | SMART INHALER: Control participants received the same Smartinhaler as intervention participants, but it did not have the audiovisual reminder device (n = 55) | Yes for improving adherence to inhalers in adults and adolescents with asthma with an audiovisual reminder | No for improving clinical outcomes with an audiovisual timer device for inhalers in asthmatic adults and adolescents |

| Choudhry 2011 | Myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease | FULL PRESCRIPTION COVERAGE: The intervention involved changing the pharmacy benefits of the intervention group patients so that they had no cost sharing for any brand or generic statin, beta‐blocker, ACE inhibitor or ARB for every prescription after randomization (n = 2845) | USUAL PRESCRIPTION COVERAGE: Control patients received usual prescription‐drug coverage (n = 3010) | Yes for improving adherence to prevention medications after MI by providing full coverage pharmacy plans | Yes for reduction in health expenditure and improving rates of first major vascular events |

| Chung 2011 | HIV | COUNSELING: In the adherence counseling intervention, trained counselors administered 2 counseling sessions to participants prior to HAART initiation and a third session 1 month after HAART initiation. Counseling sessions around HAART initiation were based on a model of successful antiretroviral adherence promotion at a large University of Washington‐affiliated HIV treatment program in Seattle, Washington. All counseling sessions followed a written standardized protocol and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. In the first session, counselors explored personal barriers to good adherence and taught participants about HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, antiretroviral medications, and the risks of treatment failure due to poor adherence. The second session occurred on a separate day and involved a review of a participant's understanding and readiness to begin antiretroviral medications. The third session allowed the counselor to examine practical and personal issues that the participant may have encountered on HAART. The adherence counseling intervention had been previously used and adapted at the same site in Kenya for over 2 years and was delivered in English and Kiswahili (n = 100) COUNSELING PLUS ALARM: Participants in counseling plus alarm group received both adherence counseling and alarm reminders. 3 adherence counseling sessions (2 prior to HAART initiation and 1 after HAART initiation) were conducted. All counseling sessions followed a written standardized protocol and lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. In the first session, counselors explored personal barriers to good adherence and taught participants about the HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, antiretroviral medications, and the risks of treatment failure due to poor adherence. The 2nd session occurred on a separate day and involved a review of a participant's understanding and readiness to begin antiretroviral medications. The 3rd session allowed the counselor to examine practical and personal issues that the participant may have encountered on HAART. The counseling session was delivered in English and Kiswahili. In addition, participants were given a small pocket digital alarm, which the individual was to carry at all times for 6 months. The device was programmed by the study staff to beep and flash twice a day at a time convenient to the participant when medications were to be taken. The digital alarm could not be reprogrammed or inactivated by the individual and was utilized for 6 months after HAART initiation before being disabled by study staff (n = 100) ALARM DEVICE: Participants in the alarm device intervention received a small pocket digital alarm which the individual was to carry at all times for 6 moths duration. The device was programmed by the study staff to beep and flash twice a day at a time convenient to the participant when medications were to be taken. The digital alarm could not be reprogrammed or inactivated by the individual and was utilized for 6 months after HAART initiation before being disabled by study staff (n = 100) | USUAL CARE: "At HAART initiation, the study pharmacist explained the side effects of medications and problems associated with poor adherence in a 15‐min session prior to dispensing drugs. All participants, including those in the control arm, received this educational message. Participants randomized to the control group did not receive adherence counseling or an alarm device." (pg 2‐3) (n = 100) | Yes for improving adherence to medication at 1 month in the counseling group; No for improving adherence to medication at 18 months in counseling group; No for improving adherence to HAART in alarm group at any time point | Yes for reducing viral failure in counseling group. No for improving mortality and CD4 cell count in counseling group. No for reducing viral failure, CD4 cell count and mortality in alarm group |

| Colcher 1972 | Strep throat | Special counseling and written instructions on need to take all pills (n = 100) | Usual care (n = 100) | Yes | Yes |

| Collier 2005 | HIV | Serial, scripted, and supportive telephone calls from a nurse plus usual adherence support (same as control group; n = 142) | Usual support measures including in‐person counseling by a nurse at start of therapy and discretionary phone calls (n = 140) | No | No |

| Cooper 2010 | HIV | ONCE NIGHTLY REGIMEN: Patients in the once nightly regimen group received 1 x didanosine (DDI) enteric‐coated (EC) capsule 400 mg (250 mg if weight less than 60 kg), 2 x lamivudine (3TC) 150 mg tablet, 1 x efavirenz (Sustiva) 600 mg tablet each evening (n = 44) | TWICE DAILY REGIMEN: Patients in the control group received Combivir (zidovudine 300 mg + 3TC 150 mg): 1 tablet twice daily, 1 x efavirenz 600 mg tablet taken nightly (n = 43) | Yes for improving adherence with HAART with once nightly dosing versus twice daily dosing | Yes for viral load undetectable; No for HAART beliefs and intrusiveness |

| Costa 2008 | Acute myocardial infarction | TRANSDISCIPLINARY APPROACH: The transdisciplinary intervention consisted of clinical follow‐up, smoking cessation assistance, dietary advice and life style modification advice. The intervention was delivered by a team consisting of an endocrinologist, a cardiologist, a nurse and a dietician. There were 2 follow‐up assessment ‐ at 60 to 90 days after MI and 120 to 180 days after MI. In diabetic patients, capillary glycemia was measured (Advantage reagent strips, Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA), lower limbs were examined, and adherence to prescribed oral antidiabetic agents and insulin was reviewed. Those patients who were still smoking were advised to stop smoking by the nurse and also by the cardiologist. No oral medication was prescribed in this regard since these drugs are not routinely provided by the Public Health System in Brazil. After the above‐described procedures, the dietitian evaluated body weight and performed a nutritional review. This review was followed by reinforcement of healthy nutritional habits, which included information on the characteristics and amount of healthy meals according to each case and also lifestyle modification reinforcement. The management plan was formulated as an individualized therapeutic alliance among the patient and family, the physician, and other members of the health care team. Finally, patients were evaluated by the cardiologist, who completed the visit with the specific medical history, physical examination and specific complementary tests. Drug prescription by the cardiologist followed the AHA guidelines for both groups (statins, antiplatelet therapy, beta‐blockers and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors). Diabetic patients were evaluated by an endocrinologist. Drug prescription by the endocrinologist followed the American Diabetes Association (ADA) guidelines for both groups (n = 78) | CONVENTIONAL CARE: Conventional care group received regular care. Before discharge, they were visited by a dietitian who prescribed a post‐discharge diet plan after nutritional evaluation. Then they were referred to the conventional outpatient clinic for heart care, where the patients were seen only by the appointed cardiologist. Cardiologists kept a routine schedule with the patients and were seen for no more than 15 minutes. Then these participants were asked to be present at the clinic 180 days after AMI to perform a clinical examination and to obtain blood samples (n = 75) | No for improving adherence to medication in patients after myocardial infarction | No for improvement in clinical improvement index; No for reduction in rate of hospitalization and deaths; Yes for increasing compliance with diet; Yes for improving compliance with visits |

| Cote 1997 | Asthma | Extensive asthma education program plus written self managed action plan based on peak expiratory flow (PEF) (n = 50) or based on asthma symptom monitoring (n = 45) | Basic information provided plus verbal action plan could be given by physician (n = 54) | No for each intervention | No for each intervention |

| Cote 2001 | Asthma | Patients in Group Limited Education (LE) (n = 30) were given a self action plan that was explained by the on call physician. The action plan used "traffic lights" (green, yellow, red) to describe specific states of asthma control based on peak expiratory flow and symptoms and actions that the patient should take for each state. Subjects were all instructed by a respiratory therapist or study nurse in the proper use of an inhaler. In addition to what patients in Group LE received, the patients in Group Structured Education (SE n = 33) participated in a structured asthma educational program based on the PRECEDE model of health education within 2 weeks after their randomization | The patients in Group C (control, n = 35) received the usual treatment given for an acute asthma exacerbation | No | No |

| Coull 2004 | Ischemic heart disease | Intervention consisted of participation in a mentor‐led group (n = 165), through attending monthly 2‐hour long meetings in community facilities over a 1‐year period. There was an average of 10 patients per group, each led by 2 mentors. The core activities covered in the program were lifestyle risk factors of smoking, diet and exercise; blood pressure and cholesterol; understanding of and ability to cope with IHD; and drug concordance. Each mentored group was also encouraged to develop its own agenda. Input was provided from a pharmacist, cardiac rehabilitation specialist nurse, dietician, welfare benefits advisor and Recreation Services. Volunteer lay health mentors, aged 54 to 74 recruited from the local community led the groups | Both intervention and control groups (n = 154) continued to receive standard care | Yes | No |

| Dejesus 2009 | HIV/AIDS | SINGLE TABLET REGIMEN (EFV/FTC/TDF): Intervention group patients were prescribed a single‐tablet regimen consisting of efavirenz/ emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EFV/FTC/TDF) (n = 203) | ART: Control group patients were prescribed regular multi‐drug ART (n = 97) | No for change in adherence to medication in EFV/FTC/TDF arm and SBR arm at 48 weeks | No for improving QOL; Yes for improving preference of medication and ease of the regimen; Yes for HIV symptom index |

| DiIorio 2008 | HIV | MOTIVATIONAL INTERVIEWING: Intervention group receives usual adherence education and motivational interview. Participants received 5 individual MI counseling sessions with a study nurse counselor over a 3‐month period. The goal of these sessions was to help participants gain an understanding of their medication‐taking behaviors and the actions necessary to successfully maintain a high level of adherence. The counselor used a MI script to guide the interaction with the participants. During the session participants were encouraged to identify and discuss barriers to adherence, to express and resolve ambivalence about taking medications, and to support motivation to attain or maintain adherence. After each medication was discussed and an action plan developed, the counselor ended each session by summarizing the discussion and the action plan agreed upon by the participant and counselor. Session 1 was completed in‐person for all participants. Telephone sessions (for sessions 2 though 5) were conducted as needed for participants who were unable to meet the counselor in the clinic. Participants were paid USD 10 for completing the first MI session and USD 5 for each of the remaining 4 sessions. Participants in the intervention group also received a copy of the Get Busy Living video, a journal and a calendar (n = 125) | CONTROL: Participants randomized to the control group received the usual adherence education provided at the clinic. 3 nurse educators employed at the HIV clinic provided comprehensive adherence education to patients who are initiating or changing ART. They use a variety of teaching methods that were tailored for each individual based on factors such as education level, culture, type of regimen and time schedule. Patients were referred to the Get Busy Living staff when the nurse educators cleared them to begin taking their medications. Participants could continue to meet with the nurse educators for adherence assistance as needed after the initial education sessions (n = 122) | Yes for the per cent of prescribed doses taken on schedule; No for the per cent of doses taken | No for viral load and CD4 count |

| Druss 2010 | Serious mental illness | HEALTH AND RECOVERY PROGRAM (HARP): Participants in the intervention group attended up to 6 group sessions led by mental health peer specialists. Sessions covered the following topics related to chronic disease self management: 1. Overview of self management 2. Exercise and physical activity 3. Pain and fatigue management 4. Healthy eating on a limited budget 5. Medication management and 6. Finding and working with a regular doctor. During the sessions, peer educators modeled appropriate behaviors and responses, and participation from each group member helped model behavior and improve motivation for other members. Attendees are taught to develop short‐term "action plans" for choosing domains of health behavior change. This process involves identifying a problem that is of particular concern, listing ideas for solving the problem, and then developing a plan outlining specific, short‐term goals for improvement. 2 certified mental health peer specialists participated in a community‐based, 5‐day CDSMP master training course to become master trainers in the CDSMP program. Subsequently, they received 3 additional days of training from the team's principal investigator and health educator in the Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) program (n = 41) | USUAL CARE: Subjects assigned to usual care continued to receive all medical, mental health, and peer‐based services that they were otherwise receiving prior to entry into the study (n = 39) | No for improving adherence to medication in patients with severe mental illness at 6 months | Yes for improving patient activation and primary care medical services use at 6 months. No for improving physical activity, physical health‐related quality of life, and mental health‐related quality of life at 6 months |

| Duncan 2012 | HIV | MINDFULNESS‐BASED STRESS REDUCTION: MBSR aims to teach participants to respond to stressful situations ''mindfully'' ‐ a state in which one focuses on the present moment, accepting and acknowledging it without getting caught up in thoughts that are about the situation or emotional reactions. This enables people to respond to the situation by making conscious choices to respond instead of reacting automatically. The MBSR program consists of the following elements: (1) individual pre‐program intake interviews performed by the course instructor with each participant, lasting 30 minutes; (2) 8 weekly classes of 2.5 to 3 hours; (3) an all‐day silent retreat during the 6th week of the program; and (4) daily home assignments including a minimum of 45 minutes per day of formal mindfulness practice and 5 to 15 minutes of informal practice, 6 days per week for the entire duration of the course. The total in‐class contact is approximately 30 hours, and the total home assignments are a minimum of 42 to 48 hours. In addition, one to 2 additional individual interview sessions may be provided, at instructor discretion, to individual participants during the course. In addition to teaching mindfulness practices, the course includes didactic presentations that include information on stress physiology and stress reactivity. The course also addresses the effects of perception, appraisal, and attitude on health habits and behavior and on interpersonal communication (n = 40) | STANDARD CARE: Control group received standard care and went through the same assessment procedure as the intervention group (n = 36) | No for improving medication adherence in HIV patients with Mindfulness Based Stress reduction Therapy at 3 or 6 months | Yes for reducing frequency of symptoms attributable to ARTs at 3 and 6 months and distress associated with those symptoms at 3 months. No for reduction in perceived stress, depression, and positive and negative affect, at 3 and 6 months |

| Dusing 2009 | Hypertension | MULTIFACTORIAL INTERVENTION: The set of supportive measures provided for selected centers and all patients recruited in these centers is listed below. It was up to the patients to select the tools they would like to use on an individual basis. For the patient: (a) 24‐hour timer: the timer can be set to an individual time and provides an acoustic signal every 24 hours at this point of time. (b) Set of 10 reminding stickers to be positioned at prominent places at home (e.g. refrigerator and bathroom mirror). (c) Information brochure for patients with hypertension published by the German Hypertension Society. (d) Information letter for the patient. (e) Information letter the patient can give to next of kin to receive support or his therapy (e.g. spouse reminding of drug intake). (f) Home BP measurement device. (g) Booklet to document home BP measurements (n = 101) | STANDARD CARE: At the baseline visit, all eligible patients were started on study treatment with valsartan 160 mg daily for 4 weeks. Patients with controlled BP were continued on treatment with valsartan 160 mg. Patients not achieving BP values less than 140/90 mmHg by week 4 were then up‐titrated to valsartan 160 mg and HCTZ 12.5 mg as a fixed‐dose combination. Follow‐up visits were scheduled after 2 (third visit), 4 (4th visit), 8 (fifth visit), 14 (6th visit), 24 weeks (7th visit), and at the end of the observation period at 34 weeks (8h visit). Dispensing of the study drugs was as follows. At baseline, patients received MEMS bottles containing 48 tablets of 160 mg valsartan. At 4th and 5th visits, that is, after 4 and 8 weeks, patients received further MEMS bottles containing 48 tablets of either 160 mg valsartan or 160 mg valsartan and 12.5 mg of HCTZ depending on their BP. At 6th and 7th visits, that is, after 14 and 24 weeks of treatment, patients received MEMS bottles containing 76 tablets. Patients were instructed to take their medication per mouth with water in the morning between 0700 and 1100 hours, regardless of meals. No supportive measures were given to patients (n = 105) | No for improving adherence outcome in patients with essential hypertension with the use of supportive measures | No for reduction in BP |

| El Miedany 2011 | Rheumatoid arthritis | VISUAL FEEDBACK: The active group consisted of a visual feedback facility (visualization of computer charts showing the disease progression) that was added to their management protocol. Visual feedback is a relatively new tool that enables the patient to visualize as well as monitor a real‐time change of their disease activity parameters as well as the patient's reported outcome measures. Integrating electronic data recording in the standard rheumatology clinical practice facilitated the introduction of visual feedback into the standard rheumatology practice. During their visit, the patients were given the chance to view the progression of their disease on the computer, discuss the changes in their disease activity parameters, comorbidity risks, functional disability, and quality of life. The patients were assessed at 3‐month intervals for another 6 months (unless they sustained a flare up of their condition, at which time they would be reviewed earlier). Before every assessment in the clinic, every patient completed the multidimensional patient reported outcome measures questionnaire (n = 55) | ROUTINE MANAGEMENT: Control group patients continued their routine standard management and assessment every 3 months. All the patient's disease activity parameters, patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs), medications, scores of falls, and cardiovascular risks were recorded and discussed verbally with the patient. Each patient was allowed to view his former completed forms and compare between his/her current scores in comparison to the earlier records (n = 56) | Yes for adherence to medication | Yes for improving pain score, patient global assessment, functional disability, quality of life, and disease activity score |

| Ellis 2005 | Adolescents with type 1 diabetes | Standard medical care plus Multisystematic Therapy (MST), an intensive, family‐centered, community‐based psychotherapy treatment with tailored treatment goals and interventions for each family to best treat the adherence problem. MST interventions targeted adherence‐related problems within the family system, peer network, and the broader community systems within which the family was embedded (n = 64) | Standard medical care at a hospital‐based endocrine clinic where adolescents were cared for consisted of quarterly medical visits with a multidisciplinary medical team composed of an endocrinologist, nurse, dietician, social worker, and psychologist (n = 63) | No | No for all clinical outcomes |

| Ellis 2012 | Type 1 or 2 diabetes | MULTISYSTEMIC THERAPY: Patients in the MST group received both standard medical care and treatment sessions by 5 masters‐level therapists trained to have sufficient knowledge regarding diabetes to enable them to conduct diabetes adherence interventions with families. Treatment included 1‐hour family treatment sessions, skills practice (e.g. spending 15 minutes in home to observe a caregiver implementing a reward or consequence as part of a behavior plan), attending school meetings to provide information to staff regarding diabetes care (e.g. 1‐2 hour staff training), and attending clinic visits with families (2 hours or more) (n = 74) | TELEPHONE SUPPORT: Control patients (telephone support) received an initial home visit where the program was explained to the adolescent and primary caregiver by either a master level therapists or doctoral students in clinical psychology or social work. Weekly phone calls (approximately 30 minutes each) focused on emotional support for diabetes care using client‐centered, nondirective counseling, assessing adherence to diabetes for the previous week, reviewing readings in the blood glucose meter, and helping the adolescent identify solutions to any barriers in their diabetes care. Non‐diabetes‐related problems such as peer, school, or family relationship problems were also addressed during the call if desired by the adolescent. Telephone support therapists completed the same formal diabetes education training completed by MST therapists (n = 72) | Yes for parent‐reported adherence at 7 and 12 months; No for youth‐reported adherence at 7 and 12 months | Yes for reduction in HB1Ac |

| Evans 2010 | Coronary artery disease risk/cardiovascular risk | PHARMACIST FOLLOW‐UP: The pharmacist established goals for the patient. Goals were documented in the patient records. When any of the risk factors were uncontrolled, the pharmacist alerted the patient by telephone and mail, and the physician was notified through the patient's medical record and face to face (when possible). Patients received continuous follow‐up by the pharmacist at a minimum of every 8 weeks by telephone, mail, electronic mail, or face to face appointments. Mailed letters were reserved for patients who were successfully controlled or had been recently contacted. Information delivered during follow‐up was patient‐specific and did not require that a standard content be covered. Reasons for follow‐up included 1) To communicate relevant laboratory results, including proximity to individual targets; 2)To monitor clinical status within 7 to 10 days after the initiation or change of a drug; 3) To monitor clinical status within 7 to 10 days after experiencing an adverse event 4) To ensure that the patient was able to procure necessary follow‐up appointments 5) To provide patients with clinical goal reminders, disease‐specific information, or timely topics using periodic mailers. Emphasis was placed on conducting short follow‐up contacts that reminded and reinforced the importance of drug adherence and clinical targets. All patients were followed for a minimum of 6 months (n = 88) | SINGLE‐CONTACT GROUP: Patients met at the beginning of the study with the study pharmacist, and received a booklet about cardiovascular disease. After that meeting they received usual care and had no more contact with the study pharmacist (n = 88) | No for improving adherence to statin therapy | No for improving Framingham risk score (FRS), blood pressure, lipid profile (total cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides) and hemoglobin A1C value |