Abstract

Background

Acupuncture and related techniques are promoted as a treatment for smoking cessation in the belief that they may reduce nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

Objectives

The objectives of this review are to determine the effectiveness of acupuncture and the related interventions of acupressure, laser therapy and electrostimulation in smoking cessation, in comparison with no intervention, sham treatment, or other interventions.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register (which includes trials of smoking cessation interventions identified from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsycINFO) and AMED in October 2013. We also searched four Chinese databases in September 2013: Sino‐Med, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data and VIP.

Selection criteria

Randomized trials comparing a form of acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrostimulation with either no intervention, sham treatment or another intervention for smoking cessation.

Data collection and analysis

We extracted data in duplicate on the type of smokers recruited, the nature of the intervention and control procedures, the outcome measures, method of randomization, and completeness of follow‐up.

We assessed abstinence from smoking at the earliest time‐point (before six weeks) and at the last measurement point between six months and one year. We used the most rigorous definition of abstinence for each trial, and biochemically validated rates if available. Those lost to follow‐up were counted as continuing smokers. Where appropriate, we performed meta‐analysis pooling risk ratios using a fixed‐effect model.

Main results

We included 38 studies. Based on three studies, acupuncture was not shown to be more effective than a waiting list control for long‐term abstinence, with wide confidence intervals and evidence of heterogeneity (n = 393, risk ratio [RR] 1.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.98 to 3.28, I² = 57%). Compared with sham acupuncture, the RR for the short‐term effect of acupuncture was 1.22 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.38), and for the long‐term effect was 1.10 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.40). The studies were not judged to be free from bias, and there was evidence of funnel plot asymmetry with larger studies showing smaller effects. The heterogeneity between studies was not explained by the technique used. Acupuncture was less effective than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). There was no evidence that acupuncture is superior to psychological interventions in the short‐ or long‐term. There is limited evidence that acupressure is superior to sham acupressure for short‐term outcomes (3 trials, n = 325, RR 2.54, 95% CI 1.27 to 5.08), but no trials reported long‐term effects, The pooled estimate for studies testing an intervention that included continuous auricular stimulation suggested a short‐term benefit compared to sham stimulation (14 trials, n = 1155, RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.16); subgroup analysis showed an effect for continuous acupressure (7 studies, n = 496, RR 2.73, 95% CI 1.78 to 4.18) but not acupuncture with indwelling needles (6 studies, n = 659, RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.69). At longer follow‐up the CIs did not exclude no effect (5 trials, n = 570, RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.74). The evidence from two trials using laser stimulation was inconsistent and could not be combined. The combined evidence on electrostimulation suggests it is not superior to sham electrostimulation (short‐term abstinence: 6 trials, n = 634, RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.46; long‐term abstinence: 2 trials, n = 405, RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.23).

Authors' conclusions

Although pooled estimates suggest possible short‐term effects there is no consistent, bias‐free evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, or laser therapy have a sustained benefit on smoking cessation for six months or more. However, lack of evidence and methodological problems mean that no firm conclusions can be drawn. Electrostimulation is not effective for smoking cessation. Well‐designed research into acupuncture, acupressure and laser stimulation is justified since these are popular interventions and safe when correctly applied, though these interventions alone are likely to be less effective than evidence‐based interventions.

Plain language summary

Do acupuncture and related therapies help smokers who are trying to quit

We reviewed the evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrical stimulation help people who are trying to stop smoking.

Background

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese therapy, generally using fine needles inserted through the skin at specific points in the body. Needles may be stimulated by hand or using an electric current (electroacupuncture). Related therapies, in which points are stimulated without the use of needles, include acupressure, laser therapy and electrical stimulation. Needles and acupressure may be used just during treatment sessions, or continuous stimulation may be provided by using indwelling needles or beads or seeds taped to to acupressure points. The aim of these therapies is to reduce the withdrawal symptoms that people experience when they try to quit smoking. The review looked at trials comparing active treatments with sham treatments or other control conditions including advice alone, or an effective treatment such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) or counselling. Sham treatment involves inserting needles or applying pressure to other points of the body not believed to have an active effect, or using dummy needles that do not go through the skin, or inactive laser or electrical stimulation devices. Using this type of control means that the patients should not know whether they are receiving active treatment or not.

To assess whether there was a sustained benefit in helping people to stop smoking we looked at the proportion of people who were abstinent at least six months after quit date. We also looked at short term outcomes, up to six weeks after quit date. Evidence of benefit after six months is regarded as necessary to show that a treatment could help people stop smoking permanently.

Study characteristics

We included 38 randomised studies published up to October 2013. Trials tested a variety of different interventions and controls. The specific points used, the number of sessions and whether there was continuous stimulation varied. Three studies (393 people) compared acupuncture to a waiting list control. Nineteen studies (1,588 people) compared active acupuncture to sham acupuncture, but only 11 of these studies included long‐term follow‐up of six months or more. Three studies (253 people) compared acupressure to sham acupressure but none had long‐term follow‐up. Two trials used laser stimulation and six (634 people) used electrostimulation. The overall quality of the evidence was moderate.

Key findings

Three studies comparing acupuncture to a waiting list control and reporting long‐term abstinence did not show clear evidence of benefit. For acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture, there was weak evidence of a small short‐term benefit but not of any long‐term benefit. Acupuncture was less effective than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and not shown to be better than counselling. There was limited evidence that acupressure is superior to sham acupressure in the short term but no evidence about long‐term effects. In an analysis of the subgroup of trials where the treatment included continuous stimulation, those trials which used continuous acupressure to points on the ear had the largest short‐term effect. The evidence from two trials using laser stimulation was inconsistent. The seven trials of electrostimulation do not suggest evidence of benefit compared to sham electrostimulation.

The review did not find consistent evidence that active acupuncture or related techniques increased the number of people who could successfully quit smoking. However, some techniques may be better than doing nothing, at least in the short term, and there is not enough evidence to dismiss the possibility that they might have an effect greater than placebo. They are likely to be less effective than current evidence‐based interventions. They are safe when correctly applied.

Summary of findings

Background

Acupuncture has been used in the treatment of nicotine dependence in the West since an incidental observation in Hong Kong (Wen 1973). Opium smokers who had been treated with electroacupuncture for pain relief reported that their opiate withdrawal symptoms were less severe than they expected. Since then, various techniques of needle or electrostimulation have been used as a treatment for dependence on various addictive substances, with the specific aim of reducing withdrawal symptoms and aiding cessation. For smoking cessation, two basic techniques are used. In the first, needles may be inserted for the duration of a treatment session (often lasting 15 to 20 minutes) at the time of cessation. The treatment may be repeated on the following days. Alternatively, or in addition to this intervention, specially designed indwelling needles may be inserted, usually in ear points, and held in position with surgical tape for several days. Patients are instructed to press these indwelling needles when they become aware of withdrawal symptoms. As an alternative to indwelling needles, small seeds or beads may be attached to the ear with adhesive tape and pressed intermittently (acupressure). Descriptions also exist of the use of a surgical suture which is inserted in the ear and knotted with a bead attached (Man 1975).

Acupuncture research is complicated by different fundamental approaches to acupuncture, and by difficulties in choosing placebo controls. Currently, there are two approaches to explain the effect of acupuncture, which seem incompatible. The differences between them have important implications for research into the needle effect. In the traditional approach (Traditional Chinese Acupuncture, TCA), the needles are inserted into particular locations where, it is believed, they can correct disturbances of a force called qi that underlie the patients' illness. Other locations are not believed to have this special property, and therefore can be readily used as placebo control. This is the theory that underlies most trials of acupuncture. In a more recent approach, known as Western Medical Acupuncture (WMA) the needle effect is believed to be obtained by stimulating nerves or connective tissue (White 2009). Since nerves and connective tissue are found throughout the body, the effects of the needles are not restricted to particular locations. Therefore, according to the WMA approach, no site can be needled as a placebo control. Moreover, no truly inert placebo for acupuncture needles has yet been devised. Various devices have been introduced that cause less stimulation than needles do, but none of these has been established as a truly inert placebo (Lund 2009; Lundeberg 2008).

Acupuncture needles are usually stimulated by hand when treating most conditions. For smoking cessation, some acupuncturists stimulate the needles electrically with the intention of more precisely stimulating the release of neurotransmitters that may be involved in suppression of withdrawal symptoms (Clement‐Jones 1979). This is electroacupuncture. Others have argued that the needles are unnecessary and it is sufficient to apply the electrical stimulation through surface electrodes attached to the mastoid process or the ear. This form of treatment is variously known as neuroelectrical therapy or (when used on the head) transcranial electrotherapy. This therapy overlaps, and has to a certain extent merged with, a therapy known as Cranial Electrostimulation (CES) which developed separately, mainly in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, as a treatment for insomnia, anxiety and depression. CES has also been used for treatment of alcohol and drug dependence (Klawansky 1995). The electric current is usually sufficient to cause a mild tingling sensation, though sometimes subthreshold currents are used. Here, we combine all therapies involving application of electrical current to the head, whether to mastoid bones or to auricular acupuncture points, under the heading 'electrostimulation'. It has been argued that the precise placement of electrodes and the parameters of electrostimulation are critical for success (Boutros 1998; Patterson 1993), which we shall consider when there are sufficient studies.

As an alternative method of stimulating acupuncture points, some practitioners use pressure alone (acupressure). As with indwelling needles above, the pressure can be sustained by fixing a small ball or bead to the point with adhesive dressing; traditionally, the seed of the cowherb Semen Vaccariae was used. Others use low level laser, which is sometimes known as 'laser acupuncture' even though it does not involve needles. Low level laser therapy produces no sensation, and there is still some uncertainty whether it has a physiological effect on normal tissue including nerves, though some data suggest it may have anti‐inflammatory effects (Sakurai 2000). From the researcher's point of view, laser therapy has the advantage that both patients and practitioners can remain masked to group allocation by using defunctioned laser apparatus. This also applies to subthreshold electrostimulation therapy.

Uncontrolled studies have suggested that acupuncture reduces the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal and some high rates of initial success have been reported. For example, Fuller 1982 claimed that 95% of 194 subjects were not smoking after three treatments in one week, falling to 34% after 12 months. Choy 1983 claimed 88% success in a large study of 514 subjects but did not state the long‐term results. Clearly, only randomized controlled studies can determine whether this is more than a placebo effect.

Several literature reviews of controlled trials of acupuncture for smoking cessation have been published but their conclusions are not uniform.

We undertook a review and meta‐analysis in order to evaluate the short‐ and long‐term effects of acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy and electrostimulation for smoking cessation.

Objectives

To evaluate whether acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy and electrostimulation: a) are more effective than waiting list/no intervention for smoking cessation; b) have a specific effect in smoking cessation beyond placebo effects; c) are more effective than other interventions used for smoking cessation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials comparing acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy or electrostimulation with either no intervention, or a sham form of the intervention, or another intervention, for smoking cessation.

Types of participants

Tobacco smokers of any age who wished to stop smoking.

Types of interventions

Non‐pharmacological stimulation interventions involving needle puncture, finger pressure or laser therapy in areas of the body described by the study's author as acupuncture points, which includes points on the ear, face and body, or the related intervention of electrostimulation to the head region, through surface electrodes. Had we located any, studies using a Western acupuncture approach would have been considered separately from those using a traditional approach.

Types of outcome measures

Complete abstinence from smoking. The review has not been limited to studies where the outcome was confirmed biochemically.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register for trials conducted on any form of acupuncture, acupressure, or related laser or electrotherapy (most recent search October 2013). At the time of the search the Register included the results of searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled trials (CENTRAL), issue 8, 2013; MEDLINE (via OVID) to update 20130906; EMBASE (via OVID) to week 201336; and PsycINFO (via OVID) to update 20130828. See the Tobacco Addiction Group Module in the Cochrane Library for full search strategies and a list of other resources searched. We also searched AMED (via Ovid) on 11 Sept 2013, CNKI (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) on 24 September 2013, Wangfang Data on 25 September 2013, and SinoMed (formerly Chinese Biomedical Database) and VIP on 26 September 2013.

The free text or keyword search strategy was (acupuncture OR acupressure OR transcutaneous OR electric stimulation OR electrostimulation OR electro*acupuncture OR neuro*electric therapy OR laser therapy) combined with (tobacco OR smoking) for AMED and Chinese databases. We included terms other than acupuncture for the first time in 2002 and searches for these terms were retrospective to the earliest date available on all databases. In addition to these searches, we obtained relevant references from published reviews, clinical trials, and conference abstracts.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors (from HR, AW, LS) independently extracted data for smoking cessation rates from each report, but JL alone extracted the Chinese reports. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We were not blinded to the study authors or journal title. Where necessary and possible, we contacted authors to provide missing data.

We extracted data (where present in the report) for two time‐points: short‐term effect, i.e. the first measure after the treatment, up to a maximum of six weeks from the quit date; and long‐term effect i.e. the last time‐point used up to one year, but with a minimum of six months. The two time‐points were selected in an attempt to identify separately the possible effects of the intervention on a) cessation in the acute withdrawal period (i.e. 'Does acupuncture have any effect at all?') and b) sustained abstinence (i.e. 'Is acupuncture a clinically useful intervention?').

Where necessary, we recalculated the published data on an intention‐to‐treat basis, i.e. counting all drop‐outs and subjects lost to follow‐up as continuing smokers. We preferred sustained smoking cessation to point prevalence where these figures were available.

We noted assessment of withdrawal symptoms, but we did not extract data for reported cigarette consumption and concentrations of nicotine breakdown products (carbon monoxide [CO] or cotinine).

The primary analyses grouped studies according to the type of treatment (acupuncture, acupressure alone, laser therapy, or electrostimulation) whether given alone or as an adjunct to other interventions, as long as the other interventions were given to all groups. Studies that compared the effect of sustained stimulation (beads or needles) of auricular points with sham points were included in another analysis (new for this update of the review), regardless of any other intervention used at the time of quitting. Previous versions of this review considered adjunctive acupuncture as a separate group, in case the effect of acupuncture was not measurable because of the other intervention. However, many studies used some level of psychological intervention making it difficult to set a threshold. It seems preferable to combine studies even if the effect of acupuncture might be subsidiary to another intervention and therefore small or even negligible. We considered different acupuncture approaches (needling of body, face, and ear) together for the primary analysis, with a further analysis of studies that used some form of continuous stimulation. We compared short‐ and long‐term outcomes for acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy and electrostimulation individually with different control procedures (i.e. no intervention, sham therapy, and other active treatment control). We compared interventions with controls in the order appropriate for research into an existing therapy (Fonnebo 2007). In each case, we calculated a weighted estimate of the risk ratio (RR), with a positive outcome shown as greater than 1, using a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect model with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assessed the amount of statistical heterogeneity between trials using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). Values of 30 to 50% can be regarded as representing moderate, and values of over 50% as substantial. We did not report pooled estimates where heterogeneity was high. Where heterogeneity was moderate we assessed whether the size and significance of the estimated effect was sensitive to the choice of meta‐analysis method by testing the effect of pooling using a random effects model.

We tabulated comparisons between included studies that compared two types of acupuncture, but did not use meta‐analysis.

Acupuncture is a highly distinctive intervention; choosing a suitable sham control for acupuncture is essential for patient blinding, but is not easy (White 2001). Two types of sham acupuncture that are commonly used are a) needling an area that is not a recognised 'point', and b) needling a point which is believed to be ineffective for the condition. It is possible that inserting a needle in any location has some general physiological activity relevant to smoking cessation (Lewith 1995). Therefore, the ideal control procedure for acupuncture research would be one that does not involve penetration or stimulation of the skin and yet appears to the participant to be a needle penetrating the skin. Non‐penetrating sham needles have been developed, but have not so far been used in research into smoking cessation. For smoking cessation, all studies so far have adopted the usual classical convention that the effects of acupuncture are point‐specific, and tested that hypothesis.

However, it has been recognised that the control point that is chosen as an 'ineffective' point might have some specific effect on the condition. For example, in a review of acupuncture for asthma, points that were chosen for control groups in some studies because the researchers considered them to be ineffective for asthma were used by other groups as the active intervention (Jobst 1995). In this review, therefore, in response to earlier comments, we examined the points used as controls in each study and checked these against the active points used in the other studies and in two literature reviews of studies of acupuncture for smoking cessation (Zhang 1992, including 48 studies, and Jiang 1994, including 64 studies). Our principal analysis included all studies, i.e. including those in which the control group may have received active treatment. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding those studies with possibly active control points.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed the risk of bias in each study based on the adequacy of sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and other sources of bias using the methods of the current Cochrane Handbook. We did not consider bias from selective reporting since we only extracted data on smoking cessation. For adequacy of blinding, we assessed participant blinding for acupuncture/placebo acupuncture comparisons, and assumed blinding when the two interventions were designed to appear identical even if the word 'blind' was not stated; we assumed all other comparisons were not blinded. For judging whether incomplete outcome data had been addressed, we classified studies as being at low risk of bias for this item if there was a clear description of numbers randomised and lost to follow‐up in each treatment group, and numbers lost were not high and were not substantially different between groups. Following the recommended methodology for Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group reviews, we assumed that all randomised participants who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up were smoking. If numbers lost to follow‐up were substantially different between groups, so that the relative effect was sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of dropouts, we classified the risk of bias as uncertain. If losses to follow‐up seemed to have been ignored so that it was not possible to construct an intention‐to‐treat analysis with drop‐outs as smokers, the risk of bias was regarded as high. In judging whether the study is free from other bias, we mainly considered baseline differences in possible response predictors, such as duration of smoking and number of previous attempts to quit.

We included all studies in the analysis, regardless of the risk of bias, since this was uncertain for a high proportion of studies. We planned to interpret any positive findings by conducting a subgroup analysis of only those studies with low risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

We identified 38 studies which qualified for inclusion in the review: 23 of acupuncture; five of acupressure; three of laser stimulation and seven of electrostimulation. Twelve studies also used continuous auricular stimulation in combination with acupuncture, acupressure or electrostimulation. Three acupuncture studies, detailed below, are each treated as two studies in the analyses giving a total of 41 in the Characteristics of included studies table. Three studies have only been reported in abstracts (Antoniou 2005; Docherty 2003; Scheuer 2005). Three were published in Chinese (Han 2006; Huang 2012; Li 2009), five in French (Labadie 1983; Lacroix 1977; Lagrue 1980; Vandevenne 1985; Vibes 1977), one in Italian (Circo 1985), and the remainder in English. See Figure 1 for a flow diagram of papers assessed for current update, in which five new included studies were identified.

1.

Flow diagram for Update 2014

Two studies reported short‐ and long‐term results in separate papers (Clavel 1992; He 1997). Two reports each described a four‐arm trial which amounted to two parallel studies, i.e. two different intervention groups each with its own control group. In both cases, we considered these as two separate studies, Martin 1981a/ Martin 1981b and Parker 1977a/ Parker 1977b.

All studies were straightforward parallel arm design except two which were of factorial design. Clavel 1992 evaluated nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and acupuncture simultaneously in a 2x2 design. For the comparison of acupuncture with sham acupuncture, these data were interpreted as two separate comparisons, combined with real or placebo NRT. We treated the arms using active NRT as a separate study (Clavel 1992 +NG). For the comparison of acupuncture with NRT, acupuncture plus placebo NRT was compared with sham acupuncture plus NRT. Georgiou 1999 evaluated two modes of electrical stimulus, two locations, and active/sham stimulation simultaneously in a 2x2x2 design: data for the two active groups (active stimulation at active location, using either modulated or continuous mode) were combined and compared with the combined data from all control groups.

Thirty‐five studies contributed data to analyses pooling short‐term outcomes. These included three (Labadie 1983; Wing 2010; Zhang 2013) which only assessed abstinence after six weeks but before six months. We included these in the short‐term outcome analysis rather than excluding them; analyses were not sensitive to their inclusion. Seventeen studies contributed data to long‐term analysis one of which did not contribute short term data (Docherty 2003). Table 3 displays lengths of follow‐up available for each included study, grouped by type of intervention.

1. Lengths of follow‐up available for included studies, grouped by intervention type.

| Study ID |

Short‐term outcomes (≤ 6 weeks after quit date) |

Long‐term outcomes (≥ 6 months after quit date) |

Notes |

| Acupressure | |||

| Li 2009 | x | Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup | |

| Tian 1996 | x | x | |

| White 2007 | x | ||

| Wing 2010 | x | Short‐term follow up > 6 weeks (3 months from treatment) Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup |

|

| Zhang 2013 | x | Short‐term follow up > 6 weeks (8 weeks) Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup |

|

| Acupuncture | |||

| Bier 2002 | (x) | (x) | Data not consistent so not included in any meta‐analysis |

| Circo 1985 | x | ||

| Clavel 1985 | x | x | |

| Clavel 1992 | x | x | |

| Cottraux 1983 | x | x | |

| Gilbey 1977 | x | Also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup | |

| Gillams 1984 | x | x | Also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup |

| Han 2006 | (x) | Compares acupuncture with acupuncture, not included in any meta‐analyses | |

| He 1997 | x | x | Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup |

| Huang 2012 | x | Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup | |

| Labadie 1983 | x | x | Short‐term follow up >6 weeks (8 weeks) |

| Lacroix 1977 | x | ||

| Lagrue 1980 | x | ||

| Lamontagne 1980 | x | x | |

| Leung 1991 | x | x | |

| Martin 1981a; Martin 1981b | x | x | Also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup |

| Parker 1977a; Parker 1977b | x | Parker 1977a also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup | |

| Steiner 1982 | x | ||

| Vandevenne 1985 | x | x | |

| Vibes 1977 | x | Also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup | |

| Waite 1998 | x | x | Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup |

| White 1998 | x | x | |

| Wu 2007 | x | x | Also in continuous stimulation (indwelling needle) subgroup |

| Electrostimulation | |||

| Antoniou 2005 | x | ||

| Aycicegi‐Dinn 2011 | x | ||

| Fritz 2013 | x | ||

| Georgiou 1999 | x | ||

| Pickworth 1997 | x | ||

| Scheuer 2005 | x | x | |

| Yeh 2009 | x | Also in continuous stimulation (acupressure) subgroup | |

| Laser therapy | |||

| Cai 2000 | x | ||

| Docherty 2003 | x | ||

| Kerr 2008 | x | x | |

We were unable to interpret the data from one study (Bier 2002) which reported a significant superiority in the quit rate after the combination of education and acupuncture when compared with acupuncture alone or education alone. However, there were inconsistencies in the data as presented which were not clarified by contact with the authors, and therefore it was not possible to extract reliable data from this study for the meta‐analysis.

Research in this area has been conducted over a long period. Four studies were published in the 1970s (Gilbey 1977; Lacroix 1977; Parker 1977a; Vibes 1977), ten in the 1980s (Circo 1985; Clavel 1985; Cottraux 1983; Gillams 1984; Labadie 1983; Lagrue 1980; Lamontagne 1980; Martin 1981a; Steiner 1982; Vandevenne 1985), eight in the 1990s (Clavel 1992; Georgiou 1999; He 1997; Leung 1991; Pickworth 1997; Tian 1996; Waite 1998; White 1998), and the remainder since 2000.

Initial group sizes for Kerr 2008, Martin 1981a and Vibes 1977 were not available in the published reports and data were obtained from the authors. Results for the different arms of Clavel 1992 were obtained from the authors.

Interventions

All acupuncture studies used a traditional approach to acupuncture in choosing points nominated as specific for smoking cessation. Five studies used facial acupuncture (Clavel 1985; Clavel 1992; Cottraux 1983; Lacroix 1977; Lagrue 1980) and ten used auricular acupuncture alone (Circo 1985; Gilbey 1977; Gillams 1984; Lamontagne 1980; Leung 1991; Martin 1981a; Martin 1981b; Parker 1977a; Parker 1977b; Waite 1998; White 1998; Wu 2007). All but three of these (Lamontagne 1980; Parker 1977b; White 1998) used some form of continuous stimulation, either needle or pressure device. Eight studies combined body and auricular acupuncture (Bier 2002; Han 2006; He 1997; Huang 2012; Labadie 1983; Martin 1981b; Steiner 1982; Vandevenne 1985). Three used continuous stimulation with either indwelling needles (Martin 1981a, Martin 1981b) or seeds (He 1997; Huang 2012). Vibes 1977 used facial, body, indwelling, and sham auricular acupuncture in different groups. This review's primary analysis included all forms of acupuncture (see Methods above).

The following studies used interventions related to acupuncture: Li 2009, Tian 1996, White 2007, Wing 2010, and Zhang 2013 used acupressure alone; Cai 2000, Docherty 2003, and Kerr 2008 used laser; Georgiou 1999, Pickworth 1997, and Scheuer 2005 investigated electrostimulation given over the mastoid bone; and Antoniou 2005, Aycicegi‐Dinn 2011, Fritz 2013 and Yeh 2009 gave electrostimulation to the ear (Yeh 2009 also used continuous acupressure stimulation).

Control interventions

All studies used a Traditional Chinese Acupuncture approach in regarding the point location of stimulation as significant and regarding non‐acupuncture points as a control intervention.

Three studies used points for the control group that were intended by the authors to be inactive but could be considered, using a neurological approach, to be active (see Methods). Gilbey 1977 used the auricular point 'Kidney' in the control group, which is reported in a review as used for smoking cessation (Zhang 1992). He 1997 used the point LI10 in the control group, which was used in treatment by another study (Jiang 1994). Lamontagne 1980 used body points including ST36 for relaxation as a control. The point ST36 is reported as an active treatment in the review by Zhang, and in one of the studies in this review (Vibes 1977). We tested the sensitivity of the pooled estimates to the exclusion of these studies

Patients in four control arms were given interventions that are of unknown effect: Circo 1985 compared acupuncture to medical treatment with vitamins and a herbal medicine, extract of hawthorn; Clavel 1992 compared acupuncture with a locked cigarette case controlled by a time‐switch; Cottraux 1983 compared acupuncture with placebo capsules; and Labadie 1983 compared acupuncture with 'medical treatment' consisting of advice, a benzodiazepine drug, lobeline, and a 'detoxicant'.

Four studies had more than one control group and therefore qualified for entry into more than one comparison: Cottraux 1983 compared acupuncture with a counselling and psychological approach, with waiting list, and with placebo capsules; Gillams 1984 compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture and with group therapy; Lamontagne 1980 compared acupuncture with sham body acupuncture and with a no‐treatment control arm; and Leung 1991 compared acupuncture with behaviour therapy and with waiting‐list control.

Han 2006 and Vibes 1977 compared different acupuncture approaches with each other.

Risk of bias in included studies

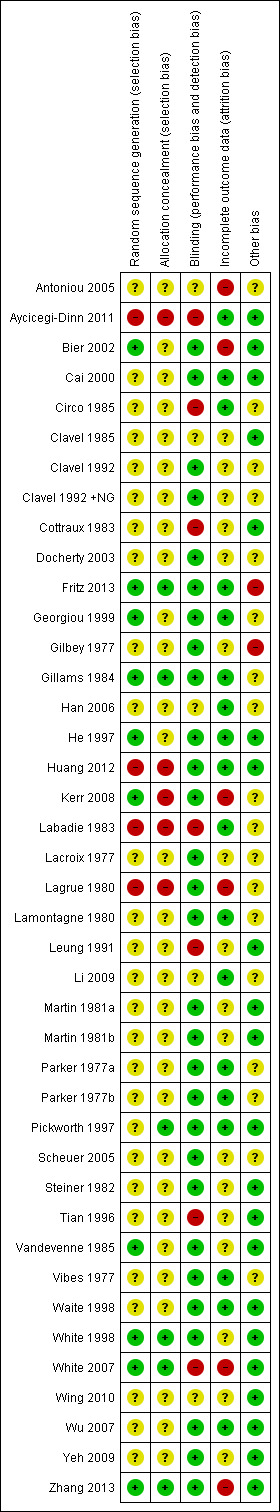

The risk of bias was judged unclear in many studies because of lack of detail in the reports, mainly associated with the facts that the older studies were published before current standards of reporting were widely applied, and several studies were published only as abstracts. In particular, methods of randomisation and allocation concealment could often not be assessed, and baseline comparisons between groups were often not reported. Apart from the lack of participant blinding in open studies, there was judged to be known risk of bias in the following studies: Antoniou 2005; Aycicegi‐Dinn 2011; Bier 2002; Fritz 2013; Gilbey 1977; Huang 2012; Kerr 2008; Labadie 1983; Lagrue 1980; White 2007; Zhang 2013 (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture for smoking cessation.

| Acupuncture compared to sham acupuncture for smoking cessation | ||||||

|

Patient or population: People trying to stop smoking

Intervention: Acupuncture Comparison: Sham acupuncture | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative rates* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed cessation rate | Corresponding rate | |||||

| Sham acupuncture | Acupuncture | |||||

| Smoking cessation Follow‐up: 6+ months | Study population | RR 1.1 (0.86 to 1.4) | 1892 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,3 | No evidence of long‐term benefit, though evidence of short‐term effect (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.38) | |

| 108 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (93 to 152) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias unclear for some domains in most studies; however, as pooled result did not detect an effect, risk of bias did not significantly alter authors' confidence in result. 2 There was clinical heterogeneity in the type and duration of acupuncture used, but little statistical heterogeneity (I² = 23%). 3 There was some evidence of funnel plot asymmetry.

Summary of findings 2. Acupressure compared to sham acupressure for smoking cessation.

| Acupressure compared to sham acupressure for smoking cessation | ||||||

| Patient or population: People trying to stop smoking Intervention: Acupressure Comparison: Sham acupressure | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative rates* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed cessation rate | Corresponding rate | |||||

| Sham acupressure | Acupressure | |||||

| Smoking cessation ‐ early Follow‐up: 3 to 12 weeks | Study population | RR 2.05 (1.11 to 3.77) | 312 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | No studies report long‐term follow‐up. | |

| 84 per 1000 | 173 per 1000 (94 to 318) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 One study with significant effect had shortest follow‐up 2 Small number of small studies without long‐term follow‐up

Acupuncture compared with waiting list/no intervention

For short‐term outcomes, the results of two studies showed substantial statistical heterogeneity (I² = 84%) and therefore were not combined. Both studies used auricular acupuncture, but one used sustained treatment with indwelling studs (Leung 1991) and the other used auricular needling during treatment sessions only (Lamontagne 1980). The first, using sustained treatment, was positive whereas the second was negative, which suggests that some of the heterogeneity may be explained by clinical diversity (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs waiting list/no intervention, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

Three studies provided long‐term outcome data (6 to 12 months). Combining these results did not demonstrate a significant effect of acupuncture (n = 393; risk ratio [RR] 1.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.98 to 3.28, Analysis 1.2), and there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity (I² = 57%).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Acupuncture vs waiting list/no intervention, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

Acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture

Short‐term outcomes

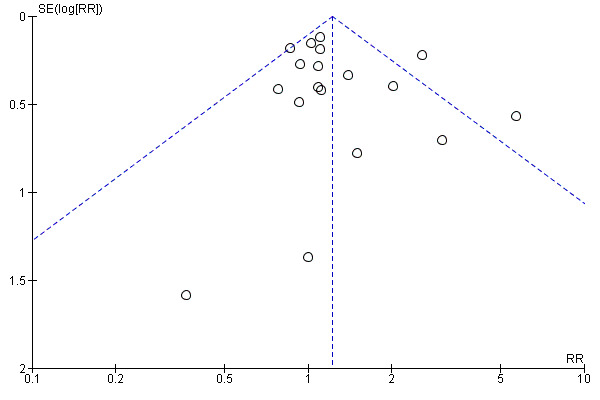

The 16 studies (19 comparisons, 2588 participants) which measured a short‐term outcome of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture combine to give an overall positive result (RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.08 to 1.38) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 46%) (Figure 3, Analysis 2.1). A funnel plot shows asymmetry, with larger studies typically showing smaller effects, and an absence of small negative studies (Figure 4). We did not conduct a subgroup analysis of high quality studies since no study was judged to be at low risk of all types of bias. Two studies individually detected a significant effect in favour of the intervention. The first, Lacroix 1977, had 117 participants and an RR of 2.58 (95% CI 1.66 to 4.01). We cannot identify any particular clinical or methodological features that might explain why this study detected a significant positive effect, although we note that the baseline characteristics of the groups are not reported so we cannot exclude confounding of the results by inequality between the groups in predictor variables. The risk of bias was unknown. The second, Huang 2012, had 60 participants and an RR of 5.67 (95% CI 1.85 to 17.34). It used an intensive intervention consisting of continuous acupressure and daily acupuncture, initially. This study was judged to be at high risk of bias.

3.

Analysis 2.1: Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture, Short‐term smoking cessation

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture, outcome: 2.1 Short‐term smoking cessation

A sensitivity analysis excluding three studies that used possibly active controls (Gilbey 1977; He 1997; Lamontagne 1980) produces a similar RR of 1.22 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.39) with moderate heterogeneity (I² = 50%). This suggests that the theoretical methodological problem of possibly active control interventions has little effect on the outcome in practice.

Longer term outcomes

The nine studies (11 comparisons, 1892 participants) with long‐term (6 to 12 month) outcomes do not show any relative effect of acupuncture compared with sham (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.40, Figure 5, Analysis 2.2), with little evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 23%). As before, the subgroup that excluded possibly active controls had a similar pooled estimate.

5.

Analysis 2.2: Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture. Long‐term smoking cessation

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

Acupuncture compared with other interventions

Acupuncture was less effective than NRT (two studies, n = 814, Analysis 3.1) both in the short term (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.98) and in the long term (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.98), with no heterogeneity. Acupuncture showed no difference of effect from counselling and psychological approaches (three studies, n = 396, Analysis 3.2) at either the short‐ (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.26) or long‐term (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.24) time points, but there was evidence of heterogeneity (I² = 43% for short‐ and I² = 64% for long‐term outcomes).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture vs other intervention, Outcome 1 NRT.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture vs other intervention, Outcome 2 Counselling and psychological approaches.

There were four trials of acupuncture compared with interventions of unknown effect (Analysis 3.3). In a large trial that was judged to be at risk of bias, acupuncture proved superior to a time‐locked cigarette case (Clavel 1985) in both the short term and long term. Acupuncture was superior to placebo capsules at end of treatment, though not in the long term (Cottraux 1983). Acupuncture was not different in effect from the use of illustration material (Circo 1985) or a combination medication product (Labadie 1983).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Acupuncture vs other intervention, Outcome 3 Interventions of unknown effectiveness.

In the studies comparing different types of acupuncture (Table 4), body acupuncture in addition to auricular acupuncture was not more effective than auricular acupuncture alone (Han 2006). Acupuncture to the Zero point in the ear and classical body acupuncture appeared more effective than other approaches, but were not statistically compared (Vibes 1977).

2. Comparisons of different forms of acupuncture.

| Study | Type of acupuncture | N included | Not smoking (early) | Success rate |

| Han 2006 | body points only | 22 | 16 | 73% |

| Han 2006 | body and auricular points | 20 | 11 | 55% |

| Vibes 1977 | classical (body) points | 44 | 14 | 32% |

| Vibes 1977 | Zero point (ear) | 39 | 11 | 28% |

| Vibes 1977 | Lung point (ear) | 34 | 3 | 9% |

| Vibes 1977 | nose points | 48 | 4 | 8% |

| Vibes 1977 | sham control (hands/feet) | 30 | 2 | 7% |

Acupressure compared with usual care or advice only

Two studies compared acupressure with usual care or advice alone in the short term (Analysis 4.1). Their results show considerable heterogeneity (I² = 91%) so we did not combine them. One was a large trial using four ear points, and was positive in both short and long term (Tian 1996). The second was a small pilot study using one or two ear points, and showed no effect (White 2007) at short term, with no long‐term outcome.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acupressure vs waiting list/no intervention, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

Acupressure compared with sham acupressure

Comparing acupressure with sham, three studies (253 participants) combined showed that acupressure to the correct points was more effective for short‐term cessation than acupressure to points deemed ineffective (RR 2.54, 95% CI 1.27 to 5.08) (Analysis 5.1). No studies had long‐term outcomes.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Acupressure vs sham acupressure, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

We found no studies comparing acupressure with other smoking cessation interventions.

Continuous auricular stimulation

Nine trials using acupuncture (Gilbey 1977; Gillams 1984; He 1997; Huang 2012; Martin 1981a; Martin 1981b; Parker 1977a; Vibes 1977; Waite 1998; Wu 2007), three using acupressure (Li 2009; Wing 2010; Zhang 2013), and one using electrostimulation (Yeh 2009) also used continuous stimulation. The stimulation was provided by indwelling needles in seven comparisons (Gilbey 1977; Gillams 1984; Martin 1981a; Martin 1981b; Parker 1977a; Vibes 1977; Wu 2007) and acupressure in the others

In the short term, continuous auricular stimulation was more effective than sham stimulation (13 studies, n = 1155, RR 1.69, 95% CI 1.32 to 2.16, I² = 16%, Analysis 6.1, Figure 6). However, for long‐term outcomes, pooled results from five studies (six comparisons, 570 participants) did not detect an effect (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.74, I² = 22%, Analysis 6.2). In both analyses, there was evidence of funnel plot asymmetry, with larger studies typically reporting smaller effects (funnel plot for short‐term outcomes Figure 7).

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Continuous auricular stimulation vs sham stimulation, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

6.

Analysis 8.1: Continuous auricular stimulation vs sham stimulation. Short‐term smoking cessation

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Continuous auricular stimulation vs sham stimulation, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

7.

Funnel plot of continuous auricular stimulation vs sham stimulation, Short‐term smoking cessation

Laser therapy

There are no comparisons of laser therapy with waiting list or no intervention controls or with other interventions for smoking cessation. Two reports of studies comparing laser with sham laser showed considerable heterogeneity in their results (I² = 97%) and were not combined (Analysis 7.2). The heterogeneity may be due, at least partly, to diversity in the participants and dose of laser, and is discussed below.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Laser therapy vs sham laser, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

Electrostimulation

There are no comparisons of electrostimulation with waiting list or with other interventions for smoking cessation. Electrostimulation was not more effective than sham electrostimulation either in the short term (six studies, n = 634, RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.46, Analysis 8.1) or the long term (two studies, n = 405, RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.23, Analysis 8.2).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Electrostimulation vs sham stimulation, Outcome 1 Short‐term smoking cessation.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Electrostimulation vs sham stimulation, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

Discussion

There is a lack of studies on acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation with large sample sizes and low risk of bias. This review is also generally limited by having to combine a wide range of interventions often used in combination. Further, the evidence does not have strong theoretical underpinning since interventions are based on traditional practice rather than neurophysiological knowledge. Below, we discuss the evidence in relation to both effectiveness (the overall effect including 'placebo' effects, tested by comparing with waiting list and with other intervention) and efficacy (comparing with sham) for each of the four related interventions, before commenting generally about possible mechanisms of action and difficulties in this research area.

Evidence of effectiveness and efficacy

We found inconsistent evidence on whether acupuncture is effective overall for smoking cessation when compared with no intervention, in open studies. The acupuncture methods used in the studies were dissimilar but not sufficiently different to explain the heterogeneity convincingly: positive results were associated with the use of indwelling needles (Leung 1991) and with three weekly treatment sessions (Cottraux 1983). We found no evidence that acupuncture was more (or less) effective than behavioural interventions used for smoking cessation. The combined results of two large studies (Clavel 1985; Clavel 1992) found acupuncture less effective than NRT, though neither study is free of bias, and in the first the acupuncture was given on only one occasion and so may have been inadequate (see below).

We found evidence of the efficacy of acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture immediately after the intervention (Figure 3) with a RR of 1.22, though there was moderate quality evidence of no effect at the long‐term follow‐up (Figure 5, Table 1). This evidence appears to suggest that acupuncture may have physiological effects relevant to smoking cessation. This result may underestimate the effect of acupuncture, since sham acupuncture may be an effective intervention, as has been suggested by three‐arm studies for painful conditions (Cummings 2009). No studies in this review compared acupuncture with both sham and with no intervention. The strength of the evidence is that it includes 19 comparisons and 2588 smokers from a wide range of countries and settings. However, the findings would be more convincing if a) the effect were sustained, b) the studies were free of bias, and c) the evidence showed consistency, or at least heterogeneity that could be explained. The limitations of the evidence are as follows. Firstly, the eight studies with long‐term follow‐up showed no effect. Both positive studies (Huang 2012; Lacroix 1977) had no long‐term follow‐up. Secondly, no study was judged to be free of the risk of bias (Figure 2). The two studies with least risk of bias were negative (Clavel 1992; White 1998), and the two positive studies were at risk of bias for two or more items (Figure 2). Thirdly, inspection of the forest plot (Figure 3) does not give the overall impression of evidence of an effect: results of twelve studies are very close to the zero line of nil effect, and the positive combined result is highly dependent on two clearly positive studies (Huang 2012; Lacroix 1977). Finally, the funnel plot (Figure 4) shows that larger studies are more likely to show no effect, which suggests the possibility of publication bias.

The combined evidence would seem stronger if the heterogeneity could be explained by the clinical technique used. The two significantly positive studies used different interventions: body acupuncture and continuous acupressure in Huang 2012 and facial acupuncture only in Lacroix 1977. The three studies with strong positive trends used other combinations of different techniques: He 1997 used body electroacupuncture, ear acupuncture and continuous acupressure; Waite 1998 used a single session of electroacupuncture to the ear with continuous stimulation; and Vibes 1977 used body, face, and auricular acupuncture in different groups. The one technique that appears promising is continuous stimulation: pooled results from 14 studies that used continuous stimulation, whether acupuncture or acupressure (Analysis 6.1), showed a positive effect of RR 1.69 (95% CI 1.32 to 2.16) compared with sham stimulation. The positive result persisted in the seven studies that used acupressure (RR 2.49, 95% CI 1.61 to 3.85) but not the seven that used indwelling needles (RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.69). This result suggesting that continuous stimulation could be a useful intervention should be interpreted with caution: there was no effect on long‐term outcomes, which indicate the value of the intervention in practice (Analysis 6.2). Furthermore, this analysis was not included in the original review protocol and was added in response to the large number of studies that used continuous stimulation as a second intervention. Inclusion of this analysis could be a bias in the review process, and the analysis could be regarded as exploratory ‐ although continuous stimulation was described as one of two 'basic techniques' in our Background, so it is logical to include its effectiveness as one of the study objectives.

For acupressure, we found conflicting evidence on acupressure compared with advice alone: one larger study was positive (Tian 1996) though with uncertain quality, and the negative study was a small pilot study (White 2007) not designed to test effectiveness. There was low quality evidence showing that acupressure was superior to sham acupressure in the short term, though of the three included studies, none was free of risk of bias and none included long‐term outcomes (Table 2). Thus we interpret the evidence as insufficient to make conclusions that would change practice, but sufficient to recommend further studies.

For laser stimulation, one study (Kerr 2008) is strongly positive at both short‐ and long‐term outcomes. Its results are inconsistent with the other two studies which show no trend. This heterogeneity may be explained by two factors. The studies differed in participants: Cai 2000 included adolescents smoking as little as five cigarettes a day, Docherty 2003 recruited adults from a socioeconomically deprived area, and Kerr 2008 included adults with no restriction. They also differed in dose of laser: Cai 2000 used 4 minutes at 3mW, whereas Kerr 2008 used 14 minutes at 50mW which is considerably higher; the dose used by Docherty 2003 is not reported in the report available. On this evidence, the effectiveness of laser stimulation for smoking cessation, at adequate dosage, justifies further investigation.

For electrostimulation, six studies are consistent in their results which did not detect an effect at short‐term outcomes, and there is no evidence of long‐term effect. This evidence gives confidence that electrostimulation, used in the locations and regimes tested here, does not have any effect beyond placebo for smoking cessation.

Possible mechanism of action

Overall, there is not sufficient evidence to rule out an effect of acupuncture, acupressure and laser stimulation on smoking cessation. We should consider their possible mechanism of action in relation to justifying further research. According to current theory, these interventions stimulate peripheral nerves to generate relevant effects in the central nervous system. Animal experiments have suggested that acupuncture might have effects on the acute withdrawal syndrome (Cheng 1980; Choy 1978; Han 1993; Ng 1975). In a classic paper, opioid peptides were released during the acute administration of acupuncture in association with relief of withdrawal symptoms in humans (Clement‐Jones 1979). Acupuncture can modify the nicotine‐induced locomotor activity and neural activity in the nucleus accumbens (Chae 2004), which is known to be a site that is crucial for chemical dependence. Other studies suggest that acupuncture may modulate dopamine release via the GABA mechanism (Yoon 2004; Yoon 2010), though other groups found evidence of enkephalin release (Liang 2010) which accumulates on repeated stimulation over three consecutive days, and yet other groups report serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine) release (Yoshimoto 2006). Brain imaging studies of acupuncture have generally focused on the limbic system in relation to pain control, though one study described fMRI (functional magnetic resonance) changes in the nucleus accumbens (Hui 2005).

While we await confirmation of these possible mechanisms and investigation of their clinical relevance, they do imply that any effect of acupuncture is likely to be via release of relevant neurotransmitters. This suggests that the duration of effect is likely to be no more than 24 hours and possibly considerably less. This has implications for both practice and research in this area.

Difficulties in this research area

Controlled trials of acupuncture are challenging in several ways, particularly defining adequate active interventions and inactive controls, and blinding participants. Clinical experience from the earliest observations in drug dependence suggests that adequate treatment involves frequent repetition ‐ at least once a day ‐ for withdrawal from opioid drugs (Smith 1988; Wen 1973). From our understanding of the possible mechanisms of action, adequate dosage with acupuncture for smoking cessation would include either several applications or a continuous stimulation. However, the evidence from the studies in this review does not give consistent support for the most effective form of intervention, presumably because the studies differ in other ways. Many studies used three weekly sessions, or indwelling needles over at least two weeks over the period of planned smoking cessation. Defining inactive controls for acupuncture is a perennial problem, since blinding of participants would seem to necessitate some form of needling. However, if the neurochemical release discussed above is a general effect of acupuncture‐like stimulation at any location (Lewith 1995), then any needle insertion in the control group is likely to be active, even if it is in a point that might be described by classically trained acupuncturists as 'not relevant for this indication'. Blunt, non‐penetrating needles have been used in research into pain control, but not yet in smoking cessation. It is challenging that, in view of the relatively small effect of acupuncture on smoking cessation, comparisons of different techniques and different controls would require large sample sizes.

Non‐pharmaceutical interventions such as those included in this review are popular and safe in the hands of trained practitioners provided that relevant precautions are taken to avoid infection. Economic data were not considered in this review, but some of the techniques related to acupuncture may have the potential to compete economically with other methods of smoking cessation such as pharmaceutical products and psychological interventions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Vincent and Richardson found that acupuncture appeared to be as effective as other methods in the initial stages of nicotine withdrawal. However there was uncertainty as to what the actual stimulation contributed and whether acupuncture helped prevent relapse (Vincent 1987). Schwartz 1988 found no evidence of a specific effect. Brewington 1994 concluded that acupuncture might be of limited assistance in withdrawal.

Ter Riet 1990 performed a criteria‐based systematic review of randomized controlled trials and concluded that on balance there was no evidence that acupuncture was efficacious in the treatment of nicotine addiction. Lewith 1995 criticised this review and argued that trials in which the controls received needling in inappropriate sites were likely to underestimate the effects of acupuncture: the control procedure was not inactive, since needling random sites could trigger the release of endorphins. He concluded that acupuncture is as effective as NRT.

Law and Tang performed a meta‐analysis of the trials listed in MEDLINE, concluding that acupuncture had "little or no effect" (Law 1995). Ashenden and Silagy (Ashenden 1997) included ten studies in a systematic review looking at the long‐term success of acupuncture in smoking cessation; nine of the studies could be combined in a meta‐analysis which concluded that, while acupuncture appeared to be promising, there was insufficient evidence to recommend it as an effective form of therapy. A meta‐analysis of 19 studies concluded that acupuncture was more effective than no, or minimal intervention, and sham acupuncture (Castera 2002).

Two recent systematic reviews of acupuncture for smoking cessation have reached different conclusions from ours. Cheng 2012 addressed a different question, combining all forms of acupuncture‐related stimulation, and all forms of control intervention in a single analysis at each time point. The review also addressed cigarette consumption. The analysis of 20 studies found that acupuncture was superior to all controls for smoking cessation (RR 1.24 immediately after treatment, 1.70 at 3 months, and 1.79 at 6 months), leading to the conclusion that "acupuncture combined with smoking cessation education or other interventions can help smokers to eschew smoking during treatment and to avoid relapse after treatment." Our review groups studies according to control intervention, addressing different research questions, which likely explains the differences in our results. Tahiri 2012 pooled long term outcomes from six sham‐controlled studies to give an odds ratio of 3.53 with 95% CI 1.03 to 12.07. Both reviews included Bier 2002, not used in a meta‐analysis here because of uncertainty about data; and both included Kerr 2008 which was categorised here as laser therapy rather than acupuncture. These uncertainties in both reviews do, in our view, preclude making conclusions about the benefits of any particular intervention related to acupuncture, and in that sense are not in conflict with our own conclusions.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is no bias‐free, consistent evidence that acupuncture, acupressure, laser therapy, or electrostimulation are effective interventions for smoking cessation. Acupuncture is less effective than nicotine chewing gum.

Implications for research.

The current evidence justifies further studies of acupuncture, acupressure, particularly sustained acupressure, and laser stimulation for smoking cessation provided that the intervention is given in adequate dosage for a sufficient period of time and compared with either no treatment, or another active intervention, or (for efficacy studies) a form of intervention that is likely to be inactive. It is relevant to continue research into acupuncture and related interventions for smoking cessation since they are popular and safe when correctly applied; however, acupuncture alone is likely to be less effective than evidence‐based interventions such as NRT. Studies could also consider economic evaluation, and the potential different roles of acupuncture used as part of a stages‐of‐change based approach. The current evidence does not support further studies of electrostimulation used in the locations and regimes tested in this review.

Feedback

Comment from Nguyen and colleagues (August 2002)

Summary

1. We wish to inform you of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) eligible in the review : Vibes J. Essai thérapeutique sur le r"le de l'acupuncturedans la lutte contre le tabagisme. Acupunct 1977;51:13‐20.

2. Three studies included in the comparison "acupuncture versus sham acupuncture" set methodological problems :

a.Gilbey 1977 should be excluded. Not only because "some authors regard kidney point (used as a control) as an effective treatment for dependency", but above all because kidney ear point is used in several clinical studies for smoking cessation. For instance, in Cui review on acupuncture for smoking abstinence [1], three studies used kidney ear point [2‐4]. b.Lamontagne 1980 should also be excluded. "Acupuncture therapy for relaxation" as control cannot be considered as sham acupuncture. That intervention uses point ST36, also used in one study of Cui review [5] and in one RCT [6] included in the meta‐analysis. Vibes RCT tests ST36, LV3, LI4 GB8, presented as "equilibrating and/or antitoxic general acting intervention". That acupuncture intervention revealed to be superior to sham acupuncture. c.In Martin 1981(a), there is discrepancy between the control group (and the total size) in the table "characteristics of included studies" and the data used in the graph : the selected control group is in fact the group "P + stimulation" of the original study. This group includes electro‐acupuncture at LI4 and "tongue" ear point. For the same motives as in the two previous studies, this control group cannot be chosen as sham acupuncture. LI4 is used in two studies in Cui review [5,7], in two RCT included in the meta‐analysis [8,9] and in Vibes study.

From a general point of view, it seems inadequate to select as sham acupuncture interventions using points employed in clinical studies dealing with the same disease. This criterion (a practical and effective use of a point) is stronger than the theoretical expert opinion, and should lead to exclude these studies in a comparison acupuncture versus sham acupuncture.

3. In the comparison "acupuncture versus sham acupuncture‐early", Waite 1998 trial is omitted without explanation. This trial has data non biochemically validated available at two weeks, that seem to meet the criteria of the review.

4. We also draw your attention to the problematic data following : a. in Parker 1977(a) and (b), the data to be selected for the size of groups seem to be the concordant ones appearing in the text and figure I (Parker (a) 18 patients: 9 for acupuncture, 9 for sham; Parker (b) 23 patients: 11 for acupuncture, 12 for sham) and not data in table 1. b. In the comparison "01 ‐Acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, 01 ‐smoking cessation early": He 1997 8/26 in acupuncture group, not 7/26.

5. In references, Lagrue 1977 is in fact Lagrue 1980.

6. Pickworth 1997 trial uses "the application of electrical currents from surface electrode...placed on each mastoid process". The authors don't identify any acupuncture points, never use the word "acupuncture" and don't mention any acupuncture study in bibliography. For that motives, including this type of studies in a review "Acupuncture for smoking cessation" seems inadequate.

From remarks 1‐4, comparison "acupuncture versus sham acupuncture" should be reconsidered.

1‐ Cui M. Advances in studies on acupuncture abstinence. J Trad Chin Med 1995;15(4):301‐7.

2‐ Cai ZM. [Ear points arousing propagated sensation for stopping smoking in Senegal]. Fujian J Trad Chin Med 1986;17(5):22‐4.

3‐ Li GJ. [33 cases of smoking cessation treated with ear point pressure]. Jianxi J Trad Chin Med 1990;21(4):40.

4‐ Requena Y, Michel D, Fabre J, Pernice C, Nguyen J. Smoking withdrawal therapy by acupuncture. Am J Acupunct 1980;8(1):57‐63.

5‐ Sacks LL. Drug addiction, alcoholism, smoking, obesity treated by auricular staplepuncture. Am J Acupunct 1975;3(2):147‐151.

6‐ Vandevenne A, Rempp M, Burghard G, Kuntzmann Y, Jung F. Etude de l'action spécifique de I'acupuncture dans la cure de sevrage tabagique. Sem H"p Paris 1985;61(29):2155‐60.

7‐ Cheung CKT. Acupuncture treatment and the preventive applications for cigarette smokers. in: Compilation of the abstracts of acupuncture and moxibustion papers. Proceedings of the 1st World Conference on Acupuncture‐Moxibustion. 1987 Nov 22‐26:Beijing,China. p.76‐7.

8‐ Steiner RP, Hay DI, Davis AW. Acupuncture therapy for the treatment of tobacco smoking addiction. Am J Chin Med 1982;10(1‐4):107‐21.

9‐ Labadie JC, Dones JP, Gachie JP, Freour P, Perchoc S, Huynh‐Van‐Thao JP. Désintoxication tabagique : acupuncture et traitement médical.Résultats comparés à 1 an sur 130 cas. Gaz Med Fr 1983;90(29):2741‐7.

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation or entity with a direct financial interest in the subject matter of my criticisms.

Reply

We are grateful to Dr Nguyen for his detailed comments.

1.Thank you for information about this trial of which we were unaware. We shall consider it for inclusion in the next review. 2.The question of appropriate and inappropriate controls runs through the whole of acupuncture research and will not be satisfactorily solved until 'Phase I & II' type studies are conducted. Without hard data, therefore, we took the pragmatic decision to accept each original author's view of what was an acceptable control. We feel it would be wrong to overturn the author's view of the sham, often very well considered and referenced, without strong reason to do so. We acknowledge that this might result in reducing the effect size for acupuncture. However, there are other biases affecting the same issue, such as the psychological equivalence of the sham control (e.g. do acupuncture studs placed in the knee have an equal psychological effect to those in the ear?). The question of whether 'acupuncture for relaxation' was an inactive control was problematic; however, there are many ways of producing 'relaxation' none of which is known to have any benefit in smoking cessation. On balance, then, we decided to keep this group in the analysis. 3.Thank you for pointing out the review omits some data reported in the Waite trial at 2 weeks. I have checked our extraction records and find that neither of the reviewers involved extracted these data, and I guess this is probably because they are only referred to very indirectly in the text, in comparison to the validated data. We therefore did not discuss whether these data are admissible. We note that they were obtained by telephone, and subsequently in the same trial, 2 out of 7 who claimed on the telephone to have stopped smoking actually were still smoking. It seems probably that all verbal reports of smoking are subject to error, but those made face‐to‐face may be more reliable than those made over the telephone; we shall discuss whether to include the latter in the next revision. 4.a) there is a clear discrepancy in group sizes in the report by Parker. We shall reconsider these extracted data at the next revision. b) In the report by He, although 8 subjects reported smoking cessation, only 7 were confirmed biochemically (see 'Tobacco consumption versus cotinine concentration'). 5.Thank you, we shall correct this in the next revision. 6.At the time of our 2nd revision conducted earlier this year, the Cochrane Group recommended including other stimulation techniques, on the basis that they should be reviewed and did not have any other natural home. We did not consider changing the review's title, but will consider this for the next revision. Thank you for the suggestion.

A R White, H Rampes, E Ernst

Contributors

Johan Nguyen (Marseilles France), Philippe Castera (Bordeaux, France), Jean‐Luc Gerlier (Annecy, France)

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 January 2014 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | No major change to conclusions |

| 26 November 2013 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. Five new studies included, none with long‐term data. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1997 Review first published: Issue 1, 1997

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 April 2011 | Amended | Graph labels corrected (reversed) for Figure 4/Analysis 3.1, Analysis 4.1, Analysis 6 & Analysis 10.2 |

| 24 November 2010 | New search has been performed |

|

| 23 November 2010 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | A Chinese author has joined the review team |

| 17 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 24 October 2005 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Title changed to include techniques related to acupuncture. Two newly discovered study included (Bier 2002; Vibes 1977). Outcome time‐points now limited to two: immediately after treatment, and last from 6 months up to one year. Studies in which acupuncture is used as an adjunct (to NRT or counselling) are now analysed separately. Comparisons modified: acupuncture now compared to other effective interventions (NRT, counselling) separately, and no longer compared with interventions of no known effect. The Mantel‐Haenzel method now used for primary method for combining studies. Subgroup analyses performed excluding studies in which the control intervention included points used as active in other studies. Analysis comparing the effectiveness of different styles of intervention is now limited to direct comparisons. |

| 18 February 2002 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Inclusion criteria for studies have been widened to cover acupressure, laser therapy, and cranial electrostimulation; which are stimulation therapies related to acupuncture and used for smoking cessation. The age limit for study participants has been removed to increase the relevance of the review. |

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ruth Ashenden and Chris Silagy for kindly giving us access to their own review of acupuncture in smoking cessation as the basis for much of the original version of this review.

We are grateful to Prof P Waite of the University of New South Wales, Australia, for providing further data for the Martin 1981a study; and to Dr F Clavel of the Unite de Recherche en Epidemiologie des Cancers, Villejuif France for providing data for the Clavel 1990 study.

We are grateful to Jie Shen, Yi‐Man Au, Jongbae Park and Sun Jin for translating and extracting data from the original Chinese reports.

We are grateful to Johan Nguyen for perceptive comments on this and an earlier version of this review, for providing one trial report of which we were not aware (Vibes 1977), and for contacting that author to obtain baseline group sizes.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Acupuncture vs waiting list/no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 3 | 393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.79 [0.98, 3.28] |

Comparison 2. Acupuncture vs sham acupuncture.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 19 | 2588 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [1.08, 1.38] |

| 2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 11 | 1892 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.10 [0.86, 1.40] |

Comparison 3. Acupuncture vs other intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 NRT | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 2 | 914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.59, 0.98] |

| 1.2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 2 | 914 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.42, 0.98] |

| 2 Counselling and psychological approaches | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 3 | 396 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.72, 1.26] |

| 2.2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 3 | 396 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.80, 2.24] |

| 3 Interventions of unknown effectiveness | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3.1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] | |

| 3.2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 3 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

Comparison 4. Acupressure vs waiting list/no intervention.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Long‐term smoking cessation | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Acupressure vs waiting list/no intervention, Outcome 2 Long‐term smoking cessation.

Comparison 5. Acupressure vs sham acupressure.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 3 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 2.54 [1.27, 5.08] |

Comparison 6. Continuous auricular stimulation vs sham stimulation.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Short‐term smoking cessation | 14 | 1155 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.69 [1.32, 2.16] |

| 1.1 Indwelling needles | 7 | 659 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.91, 1.69] |

| 1.2 Continuous acupressure | 7 | 496 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.73 [1.78, 4.18] |