Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this study was to evaluate surgical preparation methods of medical students, residents, and faculty, with special attention to video usage.

Design:

Following IRB approval, anonymous surveys were distributed participants. Information collected included demographics and surgical preparation methods, focusing on video usage. Participants were questioned regarding frequency and helpfulness of videos, video sources utilized, and preferred methods between videos, reading, and peer consultation. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS.

Setting:

Surveys were distributed to participants in the Department of Surgery at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, a tertiary care center in Iowa City, Iowa.

Participants:

Survey participants included fourth-year medical students pursuing general surgery, general surgery residents, and faculty surgeons in the UIHC Department of Surgery. Eighty-six surveys were distributed, and 78 surveys were completed. This included 42 learners (33 residents, 9 fourth-year medical students) and 36 faculty.

Results:

The overall response rate was 91%. Ninety percent of respondents reported using videos for surgical preparation (learners=95%, faculty =83%, p=NS). Regarding surgical preparation methods overall, most learners and faculty selected reading (90% versus 78%, p=NS), and fewer respondents reported preferring videos (64% versus 44%, p=NS). Faculty more often utilize peer consultation (31% versus 50%, p<0.02).

Among respondents that use videos (N=70), the most utilized source was YouTube (86%). Learners and faculty use different video sources. Learners used YouTube and SCORE Portal more than faculty (YouTube: 95% versus 73%, p<0.02; SCORE: 25% versus 7%, p<0.05). Faculty more often use society webpages and commercial videos (society: 67% versus 38%, p<0.03; commercial: 27% versus 5%, p<0.02).

Conclusions:

The majority of respondents reported using videos to prepare for surgery. YouTube was the preferred source. Posting surgical videos to YouTube may allow for maximal access to learners who are preparing for surgical cases.

Keywords: surgical education, surgical preparation, YouTube, video

INTRODUCTION

Medical professionals today have access to a multitude of training tools. As internet access is now commonplace and portable electronic devices are always within reach, the use of online resources is part of the educational armamentarium. Surgical education, in particular, has been drastically changed by the availability and vast capabilities of the internet.1 Videos are one such online tool utilized in the medical field for preparing for medical procedures, particularly by surgical residents.2

Videos are an example of multimedia learning—the incorporation of both pictures and words that may be presented in various forms to facilitate learning. Studies have shown the benefits of multimedia in the learning process, specifically in converting cognitive input into long-term memory, indicative of learning.3 Many surgical procedure videos are available, and benefits of using these videos in the surgical field have been shown, providing further support to multimedia in learning and understanding complex three-dimensional surgical procedures.4–6

Considering the benefits of videos and their convenience, it seems evident that surgeons would utilize videos while preparing for surgical procedures. However, it has yet to be explored what specific video sources surgeons are using. Additionally, it is unknown how commonly videos are used when compared to other preparation methods, such as reading text or consulting with others. The purpose of this study was to determine how surgical faculty, residents, and medical students prepare for surgical procedures, specifically focusing on video usage.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

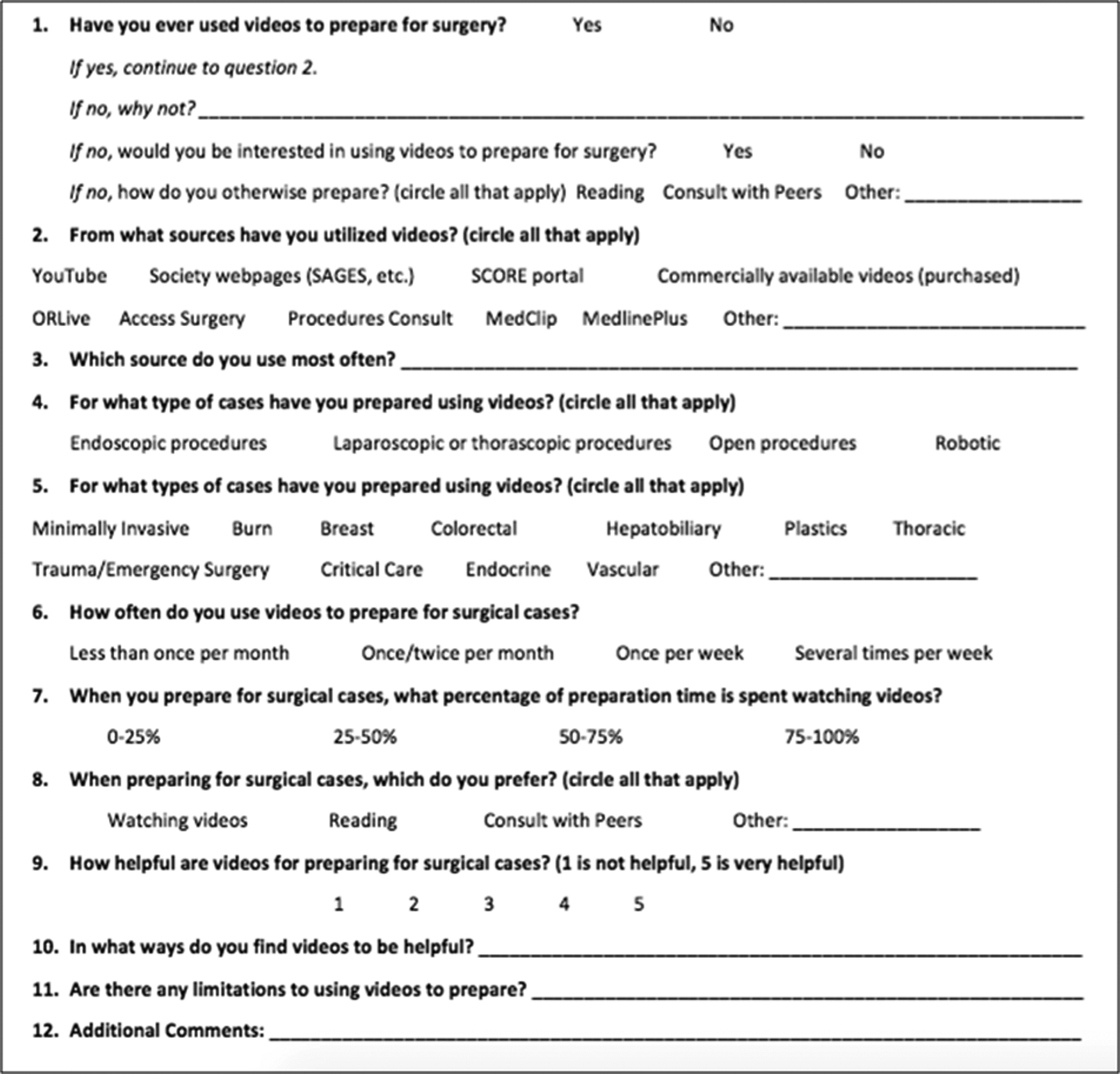

Surveys were created and distributed to general surgery faculty and residents, and fourth year medical students pursuing general surgery. The survey contained questions regarding demographics, frequency of video usage, sources of videos, procedure type prepared for using videos, helpfulness of videos, and preference in method(s) of surgical preparation. Question types included forced choice, scaled response, and open-ended. Each version contained the same 12 questions regarding surgical preparation, but demographic questions slightly differed for each group (Figure 1). The survey was pilot-tested with two of the authors and then revised prior to distribution.

Figure 1:

Survey content questions were identical for medical students, residents, and faculty. Demographic questions differed slightly for each group and are not shown.

This study received exempt status from the Institutional Review Board at the University of Iowa. Surveys were distributed to the three target groups at a single academic medical center during faculty meetings, resident meetings, and in person. Participation was voluntary and all responses were anonymous.

The SAS System (v9.3) was used to perform Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. Responses were compared between “learners” (residents and medical students) and faculty. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided p value <0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 78 surveys were completed. The overall response rate for the surveys was 91%. This included 42 learners (33 residents, 9 fourth-year medical students) and 36 faculty. Demographic information for the study participants is shown in Table 1. Learner ages ranged from 25 to 43 (mean=29 yrs). Faculty ages ranged from 32 to 70 (mean=45 yrs). Learners were comprised of residents from each clinical year (PGY 1–5) and fourth year medical students (PGY “0”). Experience among the faculty ranged from 1 to 36 years (mean=11 yrs). A wide-range of faculty sub-specialties was represented.

Table 1.

Demographic information for survey respondents

| Learners, n | Faculty, n | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | ||

| <30 | 20 | 0 |

| 30–34 | 15 | 3 |

| 35–44 | 6 | 17 |

| >44 | 0 | 16 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 25 | 25 |

| Female | 17 | 11 |

| Learner level (PGY) | ||

| 0 (students) | 9 | |

| 1 | 9 | |

| 2 | 5 | |

| 3 | 6 | |

| 4 | 5 | |

| 5 | 5 | |

| Faculty experience (yrs) | ||

| <3 | 9 | |

| 3–9 | 10 | |

| 10–20 | 8 | |

| >20 | 7 |

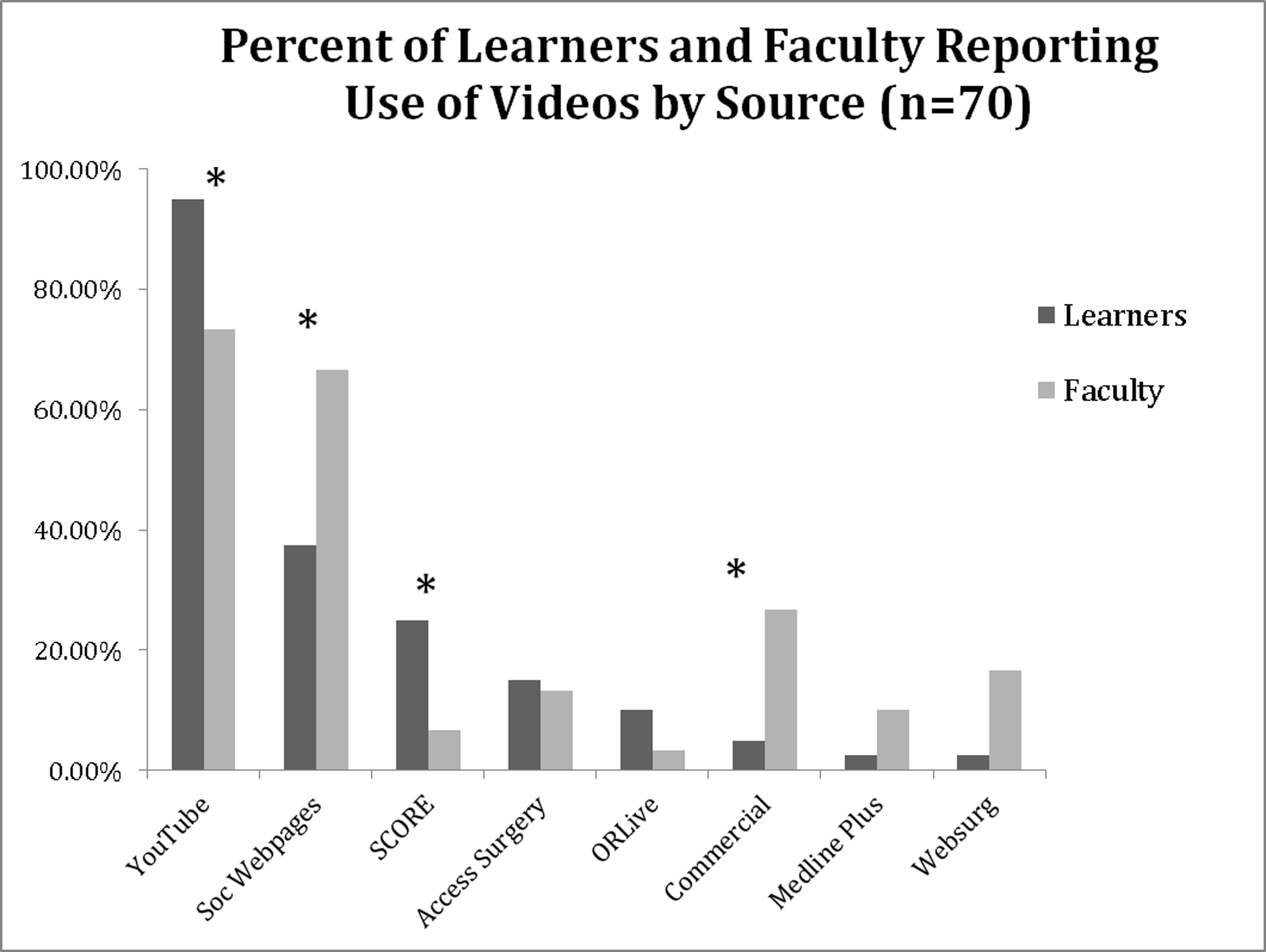

Among all survey respondents, 90% (N=70) reported using videos to prepare for surgical cases. 95% of learners and 83% of faculty reported using videos (p=NS). The reported video sources used for surgical preparation are shown in Figure 2. The most commonly reported source among all video user respondents was YouTube (86%). Learners and faculty were found to utilize different sources. Learners used YouTube (95% versus 73%, p<0.02) and the Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE) Portal (25% versus 7%, p<0.05) more than faculty. In contradistinction, faculty were more likely to use society webpages (67% versus 38%, p<0.03) and commercially available videos (27% versus 5%, p<0.02).

Figure 2:

Specific video sources used by each demographic group (learners and faculty). Stars denote statistically significant differences between the groups.

When asked to report case types for which respondents use videos, most respondents use videos when preparing for laparoscopic/thoracoscopic cases (Table 2). The next most common case type for which videos are used is open surgical procedures. This is followed by endoscopic and then robotic procedures. Learners reported using videos more so than faculty for all four case types; however, there was no significant difference between learners and faculty and case types for which videos are used.

Table 2.

Survey answers for learners versus faculty

| Learners, % | Faculty, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Types of surgical cases performed (amongst video users) | ||

| Laparoscopic/Thoracoscopic | 95 | 73 |

| Open | 58 | 53 |

| Endoscopic | 23 | 3 |

| Robotic | 13 | 10 |

| Frequency of watching videos to prepare | ||

| Less than 1 time per month* | 30 | 83 |

| 1–2 times per month* | 45 | 13 |

| 1 time per week* | 25 | 3 |

| More than 1 time per week | 0 | 0 |

| Percentage of preparation time spent using videos | ||

| 0 – 25% | 70 | 80 |

| 25 – 50% | 30 | 20 |

| 50 – 75% | 0 | 0 |

| 75 – 100% | 0 | 0 |

| Preferred methods of preparation (all survey respondents) | ||

| Reading | 90 | 78 |

| Videos | 64 | 44 |

| Peers* | 31 | 50 |

Statistically significant difference between learners and faculty

Regarding frequency of video use, most (53%) video users use videos less than once per month. Learners and faculty were found to utilize videos at different amounts of time per week or month (p<0.0001, Table 2). Learners use videos more frequently than faculty, with 70% of learners utilizing videos one to two times per month or once per week. The majority of faculty use videos less than one time per month. No respondents reported using videos more than one time per week. Additionally, all respondents who reported using videos utilize them for less than 50% of their total preparation time (p=NS, Table 2). Seventy-four percent of all respondents use videos for 0–25% of their preparation time, and 26% use videos for 25–50% of their preparation time. When asked to report the helpfulness of videos, learners and faculty, on average, reported a rating of 3.7 (range 1–5; 1=not helpful, 5=very helpful).

Regarding preferred methods of surgical preparation, most learners and faculty selected reading (learners=90%, faculty=78%, p=NS). Less respondents reported preferring videos (learners=64%, faculty=44%, p=NS), and even fewer selected peer consultation (learners=31%, faculty=50%, p<0.02) (Table 2).

Furthermore, while peer consultation is more common amongst faculty than with learners, it was found that with an increase in years of experience, use of peer consultation for surgical preparation diminishes (p<0.002). Seventy-eight percent of faculty with less than three years of experience in practice utilize peer consultation, compared to 25% of those with over twenty years of experience. Half of faculty with three to nine years and 38% of faculty with ten to twenty years of experience use peers consultation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to determine the most commonly used video sources amongst medical students, general surgery residents, and surgical faculty, with further information gathered on frequency of video use, percentage of preparation time spent using videos, and also the helpfulness of videos. It was found that the majority of respondents use videos to prepare for surgical procedures, with no statistically significant differences found between learners and faculty. However, learners and faculty utilize different video sources. Learners were found to utilize YouTube and SCORE portal more than faculty, while faculty utilize society webpage and commercially available videos more than learners. Overall, though, among all respondents, YouTube is the most reported source.

There are some clear, discernible benefits to using videos when preparing for surgical procedures. Videos can be a portable resource, available on most wireless electronic devices in a multitude of sites, allowing the user limitless control of his learning. They are also reusable resources that do not require constant maintenance. Additionally, videos do not require expert instruction nor designated times for learning. They can be accessed practically anywhere at any time. And, lastly, videos allow for the standardization of surgical education among differences in geography, time zones, experiences, and yearnings for learning. SCORE, is one such organization whose aim is standardization of surgical education.7 In addition to many others and these aforementioned benefits, the implementation of videos in surgical education curricula has already occurred.1,8

Medical students who used multimedia learning tools required less study time and had improved performance in the operating room when compared with students who prepared using text only.4 In a study where residents and medical students utilized multimedia materials to learn about a surgical procedure, it was demonstrated that multimedia-driven learning was beneficial for participant competency and motivation.9 Furthermore, videos improved resident performance when learning a surgical procedure, decreasing resident errors and staff takeovers.5 In another study, practical laparoscopic training on a simulator alone with or without the addition of video-based training was compared in a randomized controlled trial. There was a pre- and post-test design using an objective structured assessment of technical skills (OSATS). Trainees that went through both the practical and video-based training demonstrated superior technical skills compared to those that had only practical training or no training.6

Although the personal use of videos when studying and preparing for surgical cases is common, the quality of available videos is not assured. Additionally, as with print media, the issue still exists with videos in that content may not be current with today’s surgical standards. Thus, the most reliable sources may not be known or available to some surgeons. Since YouTube is one of the most highly-visited sites on the internet, the third highest in the United States, in fact, it is not surprising that our survey participants use this source frequently.10 An additional, and very paramount, limitation that must be mentioned is the issue of quality of YouTube videos. Several studies have addressed this issue and assessed the quality of YouTube videos available to view and related to specific medical procedures.11,12,13,14 These studies concluded that, although YouTube contains a wide variety of readily accessible videos, there exists enormous variability in video quality, which is highly dependent on the source of the posting. Also concluded was that some sort of ranking system should exist that clearly demarcates the reliable from the non-reliable videos. Without this ranking system, it is left to the viewers’ discretion whether or not to watch and learn from a video that may or may not be a reliable one.

There were several limitations in this study. Our study subjects were from one academic medical center; thus, the subject number in the faculty group and learner group was limited. Furthermore, faculty and learners inherently perform, or participate in, variable varieties of surgical procedures (i.e. laparoscopic/thoracoscopic, open, endoscopic and robotic). All faculty, regardless of scope of practice, were grouped together when analyzing this aspect of the study. Consequently, faculty reported a smaller variety of case types for which they utilize videos to prepare, and learners reported a larger variety of case types. Therefore, it was difficult to find correlations with various demographic groups or specialties, due to the small number of subjects within each subgroup. Finally, there was some redundancy in the survey tool, such that there was overlap with the answer choices.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we discovered that the most widely used video source used in preparation for surgical procedures is YouTube. The relatively recent increase in video availability and use presents an opportunity to create new training tools for students, residents, and faculty in the surgical field, not as a replacement, but as an addition to established teaching methods. A peer-review, or similar screening process, would need to be employed to ensure that videos recommended for learners’ education would be reliable and truly beneficial. Videos have the capability for standardization, currency, and ease-of-access for learners in the surgical field, and can serve as a widely-used and beneficial supplementation to traditional teaching methods, as an additional means of leaning surgical skills. Our findings indicate that future educational video tools should be capitalized, and posted specifically to YouTube, to result in a maximal audience for surgical case preparation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pugh CM, Watson A, Bell RH Jr., et al. Surgical education in the internet era. J Surg Res. 2009;156:177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass NE, Kulaylat AN, Zheng F, et al. A national survey of educational resources utilized by the Resident and Associate Society of the American College of Surgeons membership. Am J Surg. 2015;209:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer RE. Applying the science of learning: evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. Am Psychol. 2008;63:760–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedl R, Hoppler H, Ecard K, et al. Multimedia-driven teaching significantly improves students’ performance when compared with a print medium. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1760–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendez A, Seikaly H, Ansari K, Murphy R, Cote D. High definition video teaching module for learning neck dissection. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;43:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pape-Koehler C, Immenroth M, Sauerland S, et al. Multimedia-based training on Internet platforms improves surgical performance: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1737–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell RH. Surgical council on resident education: a new organization devoted to graduate surgical education. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:341–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moalem J, Edhayan E, DaRosa DA, et al. Incorporating the SCORE curriculum and web site into your residency. J Surg Educ. 2011;68:294–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedl R, Hoppler H, Ecard K, Scholz W, Hannekum A, Stracke S. Development and prospective evaluation of a multimedia teaching course on aortic valve replacement. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;54:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexa: The top 500 sites on the web. How popular is youtube.com? http://www.alexa.com/siteinfo/youtube.com; 2016. Accessed 15.04.08. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fischer J, Geurts J, Valderrabano V, Hugle T. Educational quality of YouTube videos on knee arthrocentesis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2013;19:373–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bezner SK, Hodgman EI, Diesen DL, et al. Pediatric surgery on YouTube: is the truth out there? J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:586–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossler B, Lahner D, Schebesta K, Chiari A, Plochl W. Medical information on the Internet: Quality assessment of lumbar puncture and neuroaxial block techniques on YouTube. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:655–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larouche M, Geoffrion R, Lazare D, et al. Mid-urethral slings on YouTube: quality information on the internet? Int Urogynecol J. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]