Abstract

Background:

Epidemiological research on effects of transportation noise on incident hypertension is inconsistent.

Objectives:

We aimed to investigate whether residential road traffic noise increases the risk for hypertension.

Methods:

In a population-based cohort of 57,053 individuals 50–64 years of age at enrollment, we identified 21,241 individuals who fulfilled our case definition of filling prescriptions and defined daily doses of antihypertensive drugs (AHTs) within a year, during a mean follow-up time of 14.0 y. Residential addresses from 1987 to 2016 were obtained from national registers, and road traffic noise at the most exposed façade as well as the least exposed façade was modeled for all addresses. Analyses were conducted using Cox proportional hazards models.

Results:

We found no associations between the 10-y mean exposure to road traffic noise and filled prescriptions for AHTs, with incidence rate ratios (IRRs) of 0.999 [95% confidence intervals (CI): 0.980, 1.019)] per 10-dB increase in road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and of 1.001 (95% CI: 0.977, 1.026) at the least exposed façade. Interaction analyses suggested an association with road traffic noise at the least exposed façade among subpopulations of current smokers and obese individuals.

Conclusion:

The present study does not support an association between road traffic noise and filled prescriptions for AHTs. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP6273

Introduction

Road, railway, and aircraft transportation all contribute to ubiquitous exposure to noise in urbanized areas, with road traffic being the most predominant source. Noise pollution is an ever increasing concern worldwide, and there is a growing body of literature purporting deleterious long-term health effects of transportation-related noise exposure (Babisch 2006; Münzel et al. 2018a; WHO Regional Office for Europe 2018). Exposure to transportation noise has consistently been linked with cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Babisch 2014; Dratva et al. 2012; van Kempen and Babisch 2012; Vienneau et al. 2015), which is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Lozano et al. 2012). Furthermore, occupational noise has been linked with hypertension in multiple studies (Chang et al. 2013; Stokholm et al. 2013; van Kempen et al. 2002), and contributes to the global burden of disease (GBD 2016 Risk Factor Collaborators 2017).

Exposure to traffic noise can induce stress, with activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal and sympathetic adrenal medullary axes, followed by the release of stress hormones (Babisch 2003; Schmidt et al. 2013; Selander et al. 2009). A suggested mechanism from noise exposure toward CVD, and more specifically hypertension, may be through autonomic reactions, including increased heart rate, arrhythmia, and increased blood pressure (Münzel et al. 2018a). Exposure to transportation noise can also impact sleep quality and duration, which may disrupt the circadian rhythm and promote oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, as well as inflammation (Basner and McGuire 2018; Miedema and Vos 2007). Nighttime noise exposure is suggested to be more relevant for the onset of CVD as compared with daytime exposure (Jarup et al. 2008), most likely owing to repeated autonomic arousals, which tend to habituate less than cortical arousals (Basner and McGuire 2018). A recent study also showed that simulated nocturnal train noise impaired endothelial function, providing a molecular explanation for increased CVD risk (Herzog et al. 2019). Current research has generally focused on noise exposure at the most exposed façade. However, many dwellings have a quiet side, which is likely where a bedroom would be located (Bodin et al. 2015). Because transportation noise impacts sleep, investigating effects of noise exposure at the least exposed façade is important.

Hypertension affects around 40% of adults globally and is responsible for over 9.4 million deaths annually (WHO 2013). A number of studies have reported on the associations between traffic noise exposure and hypertension (Dimakopoulou et al. 2017; Dzhambov and Dimitrova 2018; Fuks et al. 2017; Jarup et al. 2008; van Kempen et al. 2018; Pyko et al. 2018; Sørensen et al. 2011; Zeeb et al. 2017). A meta-analysis from 2012 including 24 studies found a statistically significant association between road traffic noise and hypertension (van Kempen and Babisch 2012). However, all the studies in the meta-analysis were of cross-sectional design (Dzhambov and Dimitrova 2018). In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) evaluated the literature on transportation noise and hypertension and concluded that the quality of evidence for an association was low to very low because the majority of the studies were of cross-sectional design or relied on self-reported data, and they also concluded that more studies of cohort or case–control design were necessary (van Kempen et al. 2018). Since the WHO evaluation, two prospective studies have been published: a Swedish cohort study that reported no significant association between road traffic noise and incident measured hypertension (Pyko et al. 2018), and a meta-analysis of seven European cohorts that found a weak association between road traffic noise and self-reported hypertension as well as self-reported intake of blood pressure–lowering medication but no association with measured hypertension (Fuks et al. 2017). The aim of the present study was to investigate, in a large Danish cohort study, the association between residential road traffic at the most and least exposed façades and register-based information on filled prescriptions for antihypertensives (AHT) as a proxy for incident hypertension.

Methods

Study Population

This study utilized data collected within the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health cohort study, which is described in detail elsewhere (Tjønneland et al. 2007). In short, from 1 December 1993 to 31 May 1997, 160,725 Danish-born citizens 50–64 years of age with no previous cancer diagnosis and living in the greater Copenhagen or Aarhus areas, were invited to participate. In total, 57,053 participants (7% of the Danish population in this age group) were recruited and completed a baseline questionnaire querying various sociodemographic and lifestyle factors, including smoking habits, physical activity, social factors, and health status. In addition, a detailed 192-item food frequency questionnaire was completed, which included fruit, vegetable, and alcohol intake (Tjønneland et al. 1991). Height, weight, waist circumference, and other anthropometric measurements were collected by trained staff, according to standardized protocols.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by local ethical committees.

Identification of Outcome

Information on filled prescriptions for AHT was collected from the Danish National Prescription Registry, which has recorded all filled prescriptions in Denmark since 1995 (Kildemoes et al. 2011). This registry contains information on the name and type of drug according to the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification system (ATC), date of dispensing, and number of defined daily doses dispensed (DDDs). The DDD is the WHO-defined maintenance dose per day for the drug’s primary indication in adults. The indication and prescribed daily dose are unavailable in the registry. Using ATC codes C02 ( agonists and others), C03 (diuretics), C07 (), C08 (calcium-channel blockers), and C09 (angiotensin-converting enzyme-inhibitors), we identified participants who filled prescriptions for orally administered AHT. To increase specificity, we counted participants as cases only if they had, within 1 y, filled two or more prescriptions and more than 180 DDDs. In sensitivity analyses, we excluded participants filling prescriptions for diuretics (ATC: C03) because these medications have various indications that could be unrelated to hypertension.

We excluded all participants who filled prescriptions for AHT based on our case definition before start of follow-up (1 July 1997) in order to include only incident cases. Using the national heath registers (Lynge et al. 2011), we also excluded participants who had been hospitalized with CVD categorized according to the International Classification of Disease, Eighth Revision (ICD 8; WHO 1966) or the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10; WHO 2016) (ICD-8, codes 390–458; ICD-10 codes I00–I99) and participants with diabetes [identified by linkage to the Danish National Diabetes Registry (NDR) (Carstensen et al. 2011)] before 1 July 1997 in order to exclude persons who were most likely prevalent cases because hypertension is often diagnosed concurrently with these diseases (Long and Dagogo-Jack 2011; Ventura and Lavie 2016).

Exposure Assessment

Complete address histories were collected for each participant from 1 July 1987 to 31 December 2016 from the Danish Civil Registration System (Pedersen 2011). Noise calculations were made in accordance with the Nordic prediction method for road traffic noise using SoundPLAN (version 8.0; SoundPLAN Nord ApS) (Bendtsen 1999). In Scandinavia, the Nordic prediction method has been the prevailing noise calculation method for more than a decade (Bendtsen 1999). We used the same noise calculation approach of road traffic noise as described previously (Thacher et al. 2020). The input variables for the noise model included three-dimensional building polygons (linked with address points and information on height), road attributes that consisted of yearly average daily traffic and traffic composition and speed, road type (motorways, rural highways, roads wider than , roads , and other roads), noise barriers, embankments, and terrain. Traffic information was gathered from a national road and traffic database that covered the years 1960–2005 (Jensen et al. 2009). Data from 1995 had the highest level of detail. Therefore, we extrapolated traffic data from the existing traffic database in 1995 to the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. To extrapolate the traffic data, information on traffic and road lengths were collected from the Danish Road Directorate (Andersen and Bendtsen 2002) and used to calculate a scaling factor for annual average daily traffic individually for motorways and other roads for the years 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 (Jensen et al. 2019). It was assumed that urban areas, roads, and bodies of water were hard surfaces (reflecting) and that other topographies were assumed to be acoustically porous (absorbent).

Noise levels were calculated at the center of all façades of each residence, and the most and least exposed façades of each residence were subsequently identified and extracted. For large apartment complexes and townhouses, there were often several address points present inside the same building polygon. Therefore, buildings with multiple address points were divided into separate building polygons for each address point. Road traffic noise exposure was estimated for each address annually as the equivalent continuous A-weighted sound pressure level () at the most and least exposed façades of each address for (0700–1900 hours), (1900–2200 hours), (2200–0700 hours), and expressed as (an indicator of overall noise levels during day, evening, and night, by applying a 5-dB penalty for the evening and 10-dB penalty for night).

Ambient concentrations of nitrogen dioxide () and particulate matter (PM) with an aerodynamic diameter of () were assessed using the validated Danish multiscale dispersion modeling system, Danish Eulerian Hemispheric Model (DEHM)/Urban Background Model (UBM)/AirGIS, for the same years as exposure to traffic noise for each participant’s residence. Details of the DEHM/UBM/AirGIS modeling system have been described in detail elsewhere (Jensen et al. 2017; Khan et al. 2019). In short, it is a high-resolution dispersion modeling system that combines contributions from local, urban, and regional sources of and (and their precursors), which are estimated using a combination of three models, the DEHM (Brandt et al. 2012), the UBM (Brandt et al. 2003), and the Operational Street Pollution Model (Ketzel et al. 2013). The DEHM/UBM/AirGIS modeling system has been successfully validated and applied in multiple studies (Hvidtfeldt et al. 2018; Ketzel et al. 2011; Khan et al. 2019).

Statistical Analysis

Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between residential road traffic noise exposure and redemption of AHT with age as the underlying timescale. We used left truncation at 1 July 1997 to ensure at least 10 y of exposure history, and end of follow-up (right censoring) at age of redemption of AHT, death, emigration or disappearance, or 31 December 2016, whichever came first.

Exposure to residential road traffic noise was modeled as time-weighted averages for the preceding 1, 5, and 10 y at a given age and accounted for all addresses in the respective periods. Time-weighted average noise levels below 35 dB(A) for road traffic noise were considered unexposed and were set at 35 dB(A) given that background noise from other sources is expected to be of around this magnitude.

IRRs were calculated for filled prescriptions for AHT in association with road traffic noise exposure. Covariates were selected a priori and adjustment was conducted in a stepwise process: 1a) age (by design), calendar year, and sex (crude model); 1b) additional adjustment for socioeconomic covariates (at baseline, July 1997) obtained from Statistics Denmark on an individual level: educational level (basic: y of education; vocational/medium: 8–12 y of education; higher: of education), disposable income (in tertiles) and cohabitation status (married/registered partnership, and other), as well as area level (parish): proportion of inhabitants with low disposable income (percentage, linear), proportion of inhabitants with only basic education (percentage, linear), and proportion of inhabitants being unemployed (percentage, linear); 1c) additional adjustment for baseline information on smoking status (never, former, current), smoking duration (years, linear), smoking intensity (grams/day, linear), alcohol intake (grams/day, linear), alcohol abstainers (yes/no), sport during leisure time (yes/no), duration of sport during leisure time (hours/week among active, linear), fruit intake (grams/day, linear), and vegetable intake (grams/day, linear); and 2) additional adjustment for time-weighted averages of and (, linear).

We explored exposure–response associations for residential road traffic noise and filled prescriptions for AHT by generating eight exposure categories with dB(A) and dB(A) as the reference categories for the most and least exposed façades, respectively, and 3-dB(A) increments (52–55, 55–58, 58–61, 61–64, 64–67, 67–70, and for most exposed façade and , 45–48, 48–51, 51–54, 54–57, 57–60, 60–63, and for the least exposed façade).

To assess potential effect modification of the association between traffic noise exposures and filled AHT prescriptions by sex, age (at event), smoking status, education level, body mass index (BMI), and calendar year, an interaction term was introduced into the model and was tested by the Wald test. Potential combined effects between road traffic noise at the most and least exposed façade were investigated by combining categories of the two exposures (10-y means) into nine categories, using the category of low noise at both façades as reference group.

The assumption of linearity of continuous variables ( at the most exposed façade, at the least exposed façade, smoking intensity, smoking duration, alcohol intake, vegetable intake, fruit intake, BMI, duration of physical activity, proportion of inhabitants with low disposable income, proportion of inhabitants with only basic education, proportion of inhabitants being unemployed, , and ) in relation to filled prescriptions for AHT was investigated by plotting the exposure–response function using smoothed splines with 4 degrees of freedom (Greenland 1995; Therneau 2017). We observed no deviation from linearity for the continuous variables (see Figure S1).

We also tested the proportional hazards assumption of the Cox models by a correlation test between the scaled Schoenfeld residuals and the rank order of event time. Sex and smoking status violated the proportional hazards assumption; therefore, the final models were conducted with these variables as strata.

The analyses were performed using the procedure PHREG in SAS® (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc.) and the pspline function of coxph for the smoothed spline predictions in the statistical software R (version 3.2.3; R Development Core Team).

Results

Of the 57,053 participants from the Diet, Cancer and Health cohort, we excluded 574 participants with a cancer diagnosis before baseline, 9,113 participants who filled prescriptions for AHT before the start of follow-up (1 July 1997), 683 participants with diabetes according to the NDR before 1 July 1997, 5,334 participants with any CVD before 1 July 1997, 48 participants with missing exposure information, 158 participants who died before 1 July 1997, 11 participants who emigrated before 1 July 1997, and 2,121 participants with missing information on covariates, leaving a total of 39,011 participants in the final study population (see Figure S2). Of the eligible 39,011 participants, 21,241 (54.4%) redeemed AHT according to our case definition during a median follow-up of 14.0 y, and 18,535 (47.5%) redeemed AHT excluding diuretics.

Participants exposed to high levels of road traffic noise at the most exposed façade [ dB(A)] at the start of the follow-up were more likely to have a basic education, to have a lower disposable income, to live alone, to be current smokers, and to report lower consumption of fruit and vegetables, and they were less likely to be male and participate in sports compared with those exposed to dB(A) (Table 1). The distribution of road traffic noise at the most and least exposed façades is presented in Figure S3. The distribution of road traffic noise at the most exposed façade was somewhat positively skewed, whereas road traffic noise at the least exposed façade was relatively normally distributed. A correlation matrix of road traffic noise and air pollution at baseline is presented in Table S1. The correlation () between road traffic noise at the most and least exposed façades was 0.45 at baseline. We observed stronger correlations of air pollution with road traffic noise at the most exposed façade than with road traffic noise at the least exposed façade.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to road traffic noise exposure at the most exposed façade at baseline.

| Variable | Total cohort () |

() | road 56–60 dB () | () |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males (%) | 47.4 | 48.7 | 46.5 | 45.8 |

| Age at baseline (y) | 57.6 (4.4) | 57.4 (4.3) | 57.7 (4.4) | 57.9 (4.6) |

| Follow-up time (y) | 13.1 (6.3) | 13.2 (6.3) | 13.0 (6.3) | 12.9 (6.3) |

| Education (%) | ||||

| Basic | 26.1 | 23.3 | 27.8 | 30.1 |

| Vocational/medium | 44.8 | 45.0 | 44.4 | 44.7 |

| Higher | 29.1 | 31.7 | 27.8 | 25.3 |

| Household income (%) | ||||

| First tertile | 18.4 | 14.5 | 20.1 | 24.5 |

| Second tertile | 30.0 | 28.6 | 30.8 | 32.2 |

| Third tertile | 51.6 | 56.9 | 49.1 | 43.3 |

| Cohabiting (%) | 72.0 | 76.7 | 70.0 | 65.5 |

| Area-level socioeconomic status | ||||

| Proportion of basic education | 23.9 (7.6) | 23.4 (7.4) | 24.9 (7.8) | 24.2 (7.9) |

| Proportion of low income | 11.2 (6.8) | 10.0 (6.1) | 11.8 (7.0) | 12.9 (7.3) |

| Proportion of unemployed | 6.1 (2.3) | 5.7 (1.9) | 6.3 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.6) |

| Smoking status (%) | ||||

| Never | 36.7 | 38.6 | 36.4 | 33.3 |

| Former | 27.5 | 28.7 | 27.1 | 25.7 |

| Current | 35.8 | 32.7 | 36.5 | 41.0 |

| Smoking duration (y)a | 28.9 (12.1) | 28.1 (12.3) | 29.2 (12.1) | 30.0 (11.7) |

| Smoking intensity (g/d)a | 17.4 (10.5) | 17.1 (10.3) | 17.5 (10.4) | 17.8 (10.8) |

| Alcohol intake (g/d) | 20.8 (21.2) | 20.5 (20.1) | 20.9 (21.3) | 21.3 (22.9) |

| Alcohol abstainers (%) | 1.9 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| Fruit intake (g/d) | 210 (162) | 211 (158) | 211 (166) | 208 (168) |

| Vegetables intake (g/d) | 180 (102) | 183 (100) | 177 (101) | 176 (106) |

| BMI () | 25.6 (3.8) | 25.6 (3.7) | 25.7 (3.8) | 25.8 (4.0) |

| Sports during leisure time | ||||

| Yes (%) | 56.6 | 59.1 | 56.1 | 52.1 |

| Hours among active/week | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.4 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Road traffic noise | ||||

| At most exposed façade [ (dB)] | 56.1 (7.5) | 50.2 (4.1) | 58.5 (1.4) | 65.7 (3.7) |

| At least exposed façade [ (dB)] | 47.9 (5.7) | 45.8 (4.6) | 50.1 (5.3) | 50.1 (6.4) |

| Air pollution | ||||

| () | 22.0 (2.1) | 21.2 (0.9) | 21.7 (1.1) | 23.8 (3.1) |

| () | 30.8 (8.0) | 27.1 (4.4) | 31.0 (5.3) | 37.8 (10.2) |

Note: Values are means (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; , indicator of overall noise levels during day, evening, and night; , nitrogen dioxide; , particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of .

Among current and former smokers.

Table 2 presents the associations between time-weighted average exposure (1, 5, and 10 y) to road traffic at the most and least exposed façades and filled prescriptions for AHT. We observed a 3.7% higher risk of filled prescriptions for AHT per 10-dB(A) higher road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and a 3.1% higher risk at the least exposed façade in the crude Model 1a [ (95% CI: 1.018, 1.057) and (95% CI: 1.007, 1.055), for 10-y mean exposure, respectively). However, following adjustment for socioeconomic status and lifestyle confounders (Model 1c), the association between road traffic noise at the most and least exposed façades and filled prescriptions for AHT were no longer apparent [ (95% CI: 0.980, 1.019) and (95% CI: 0.977, 1.026), for 10-y mean exposure, respectively]. Similar results were observed when using a case definition with higher specificity toward hypertensive indications (disregarding prescriptions for diuretics, ) (see Table S2).

Table 2.

Associations between residential exposure to traffic noise (per 10 dB) and filled prescriptions for antihypertensive medication.

| Exposure to road traffic noise (per 10 dB) | Cases (n) | Model 1aa Crude | Model 1bb | Model 1cc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [IRR (95% CI)] | [IRR (95% CI)] | [IRR (95% CI)] | ||

| Most exposed façade | ||||

| 1-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.028 (1.009, 1.047) | 1.005 (0.986, 1.023) | 0.998 (0.980, 1.017) |

| 5-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.031 (1.012, 1.050) | 1.006 (0.987, 1.025) | 0.998 (0.979, 1.017) |

| 10-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.037 (1.018, 1.057) | 1.008 (0.989, 1.028) | 0.999 (0.980, 1.019) |

| Least exposed façade | ||||

| 1-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.027 (1.004, 1.051) | 1.005 (0.982, 1.028) | 1.003 (0.980, 1.026) |

| 5-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.028 (1.004, 1.051) | 1.003 (0.980, 1.027) | 1.001 (0.977, 1.025) |

| 10-y preceding filled prescription | 21,241 | 1.031 (1.007, 1.055) | 1.004 (0.980, 1.029) | 1.001 (0.977, 1.026) |

Note: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Sex and calendar year.

As Model 1a and further adjusted for level of education, disposable income, cohabitation, area-level proportion of inhabitants with low income, basic education, and unemployment.

As Model 1b and further adjusted for smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, alcohol intake, abstainers, sport during leisure time (yes/no), sport (hours/week), vegetable intake, and fruit intake.

Inclusion of exposure to in the fully adjusted Model 1c resulted in risk estimates slightly for filled prescriptions for AHT in relation to 10-y mean road traffic noise at the most exposed façade [ (95% CI: 1.015, 1.060)], and at the least exposed façade [ (0.990, 1.039)], whereas inclusion of exposure to gave risk estimates around unity (see Table S3).

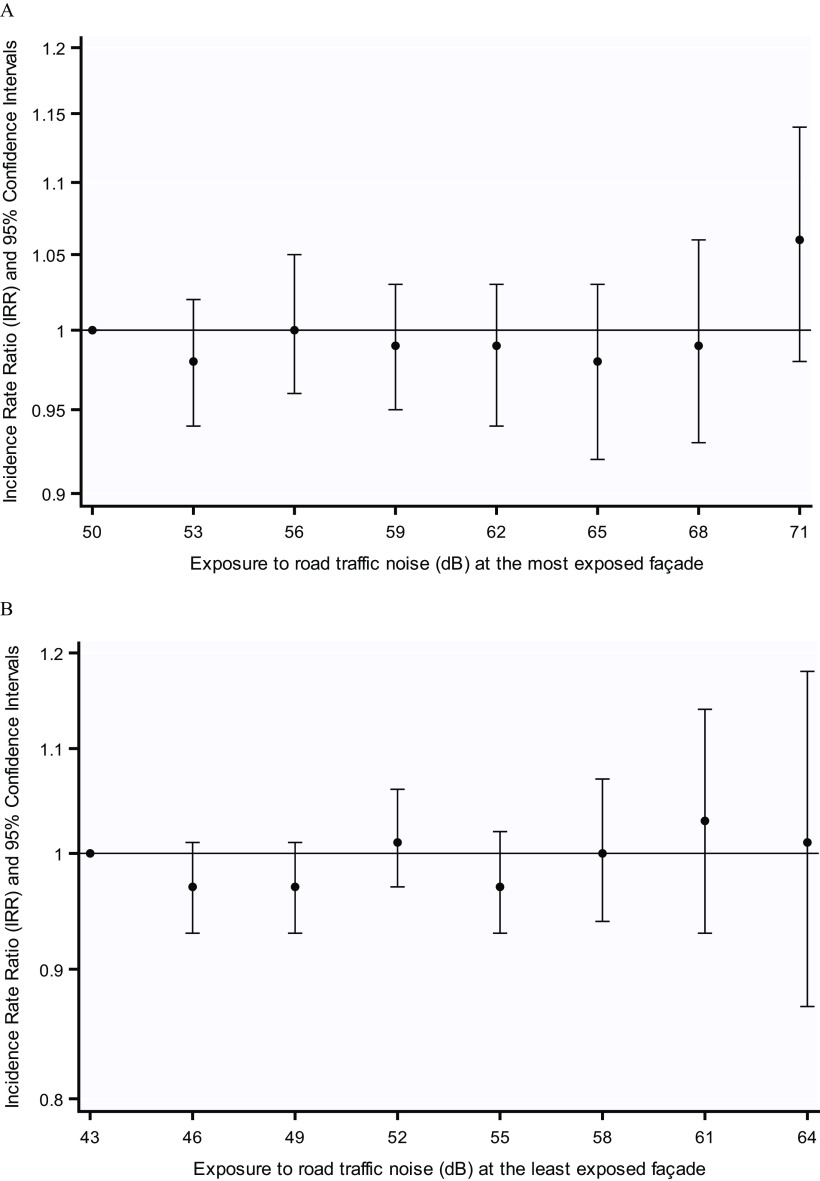

Figure 1 illustrates the IRRs for eight exposure categories at the most and least exposed façades in comparison with reference groups of dB(A) and dB(A), respectively. We observed no consistent exposure–response relationship between increasing exposure to road traffic noise at the most or least exposed façades and filled prescriptions for AHT (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Association between 10-y mean exposure to road traffic noise () at the (A) most exposed and (B) least exposed façades of the residence and filled prescriptions for antihypertensive medication. Adjusted for sex, calendar year, level of education, disposable income, cohabitation, area-level proportion of low income, basic education and unemployment, smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, alcohol intake, abstainers, sport during leisure time (yes/no), sport (hours/week), vegetable intake, and fruit intake. See Table S4 and S5 for corresponding numeric data.

Table 3 shows the association between combinations of exposure to road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and exposure at the least exposed façade in relation to risk of filled prescriptions for AHT. The results showed rather similar IRRs for any combination of noise levels at the most and least exposed façades. The association for the combination of the highest exposure to both façades was (95% CI: 0.976, 1.119).

Table 3.

Associations between categories of combined exposure to road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and the least exposed façade () at the residence (10-y mean) and risk of filled prescriptions for antihypertensive medication. {N cases [IRR (95% CI)].}

| Least exposed façade | Most exposed façade | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| dB(A) | 53–65 dB(A) | dB(A) | |

| dB(A) | 3,736 [1.000 (ref)] | 2,453 [0.971 (0.922, 1.023)] | 579 [0.989 (0.901, 1.085)] |

| 45–51 dB(A) | 2,891 [0.952 (0.906, 1.000)] | 4,452 [0.980 (0.939, 1.022)] | 880 [0.969 (0.901, 1.041)] |

| dB(A) | 54 [0.924 (0.684, 1.249)] | 4,566 [0.968 (0.927, 1.011)] | 1,043 [1.045 (0.976, 1.119)] |

Note: Model was adjusted for sex, calendar year, level of education, disposable income, cohabitation, area-level proportion of low income, low education and unemployment, smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, alcohol intake, abstainers, sport during leisure time (yes/no), sport (hours/week), vegetable intake, and fruit intake. CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio; , indicator of overall noise levels during day, evening, and night.

Associations between road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and filled prescriptions for AHT was not modified by sex, age, educational level, smoking status, BMI, or calendar year (Table 4). However, there were weak indications that the association between exposure at the least exposed façade and filled prescriptions for AHT was slightly stronger among current smokers [ (95% CI: 0.995, 1.073) vs. never smokers (95% CI: 0.958, 1.037) and former smokers (95% CI: 0.921, 1.006), ] and obese individuals [ (95% CI: 1.000, 1.122) vs. normal (95% CI: 0.948, 1.021) and overweight (95% CI: 0.955, 1.023), ] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect modification of the associations between 10-y mean road traffic noise [per 10 dB(a)] and filled prescriptions for antihypertensive medication.

| Covariates | Cases (n) | Most exposed façade | Least exposed façade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) | ||||

| Sex | 0.198 | 0.204 | |||

| Males | 10,425 | 1.012 (0.985, 1.040) | 1.017 (0.983, 1.051) | ||

| Females | 10,816 | 0.987 (0.961, 1.014) | 0.987 (0.955, 1.020) | ||

| Age (y) | 0.354 | 0.193 | |||

| 7,606 | 1.011 (0.980, 1.044) | 0.980 (0.941, 1.021) | |||

| 13,635 | 0.993 (0.969, 1.017) | 1.013 (0.983, 1.043) | |||

| Education | 0.465 | 0.163 | |||

| Basic | 6,001 | 1.008 (0.973, 1.045) | 1.032 (0.989, 1.078) | ||

| Vocational | 9,784 | 1.006 (0.978, 1.034) | 0.998 (0.964, 1.033) | ||

| Higher | 5,456 | 0.980 (0.944, 1.017) | 0.972 (0.928, 1.019) | ||

| Smoking status | 0.903 | 0.051 | |||

| Never | 7,325 | 1.000 (0.968, 1.033) | 0.997 (0.958, 1.037) | ||

| Former | 5,828 | 0.993 (0.958, 1.030) | 0.963 (0.921, 1.006) | ||

| Current | 8,088 | 1.004 (0.974, 1.036) | 1.033 (0.995, 1.073) | ||

| BMI () | 0.374 | 0.077 | |||

| Normal and underweight () | 8,346 | 1.002 (0.972, 1.033) | 0.984 (0.948, 1.021) | ||

| Overweight () | 9,525 | 0.976 (0.949, 1.004) | 0.988 (0.955, 1.023) | ||

| Obese () | 3,370 | 1.004 (0.957, 1.053) | 1.059 (1.000, 1.122) | ||

| Calendar year | 0.753 | 0.902 | |||

| Before 2005 | 8,168 | 0.996 (0.966, 1.027) | 1.003 (0.965, 1.043) | ||

| After 2005 | 13,073 | 1.002 (0.978, 1.027) | 1.000 (0.971, 1.030) | ||

Note: Model was adjusted for sex, calendar year, level of education, disposable income, cohabitation, area-level proportion of low income, basic education and unemployment, smoking status, smoking duration, smoking intensity, alcohol intake, abstainers, sport during leisure time (yes/no), sport (hours/week), vegetable intake, and fruit intake. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

We found no association between long-term exposure to road traffic noise at the most or least exposed façade and filled prescriptions for AHT in this large Danish cohort study. We observed no indication of an exposure–response relationship, nor was the association between road traffic noise at the most exposed façade and filled prescriptions for AHT modified by sex, education level, smoking status, BMI, or calendar year. There was slight indication of a stronger association between road traffic noise at the least exposed façade and filled prescriptions for AHT among current smokers and obese individuals.

The present study has several strengths: large study size, complete address histories, extensive follow-up time, detailed road traffic noise modeling, the ability to calculate noise exposure history from 1987 until end of follow-up for each participant, assessment of three exposure time windows, adjustment for various area-level socioeconomic indicators and lifestyle confounders, and the large number of cases identified through a nationwide register with high validity (Kildemoes et al. 2011). Another notable strength of the present study is inclusion of exposure at both the most and least exposed façades. Denmark has universal free health care and medication costs are heavily subsidized, limiting the potential for bias. In addition, the adjustment for air pollution, which is correlated with road traffic noise, is a strength. We adjusted for two indicators of ambient air pollution: , which has been consistently associated with CVD (Beelen et al. 2014), and , which is a well-recognized surrogate for a mix of traffic-related air pollutants (Sørensen et al. 2012).

Some limitations deserve mention. Using filled prescriptions for AHT as a proxy for hypertension results in a reduction of outcome sensitivity because we only capture diagnosed hypertension. In Denmark, around 30% of individuals with hypertension are unaware of this condition (Kronborg et al. 2009). However, as people age, this figure likely decreases as contact with the health care system becomes more frequent. In addition, physicians are cognizant of the risks hypertension poses to cardiovascular health and are vigilant in identifying and controlling hypertension. Filled prescriptions for AHT as a proxy for hypertension likely yields high specificity given that this represents the end point of multiple blood pressure measurements by medical staff and clinical examinations by physicians (Poulsen et al. 2018). Using filled prescriptions for AHT as a proxy is more accurate than single measurements of blood pressure (which can be biased by transient increases) or self-reported hypertension (which is prone to recall bias): both outcome measures have been frequently used in previous cross-sectional studies (Stokholm et al. 2013). In addition, although we tried to improve specificity by requiring more than 180 DDDs and more than two prescriptions within a year, some of the persons recorded as cases in the present study may have used AHT for other conditions. To further investigate the risk of such outcome misclassification, we excluded diuretics from our case definition in a sensitivity analysis because these drugs have a variety of indications unrelated to hypertension. We observed similar results for the more restrictive case definition as for the main case definition, suggesting that low specificity is unlikely to explain the lack of association between road traffic noise and redemption of AHT.

Some degree of exposure misclassification is unavoidable given that the modeled exposures, although of high quality, are only surrogates for the true individual exposures. In addition, we did not account for bedroom location, time spent at work (with potential occupational exposure) or holiday home, window-opening habits, individual noise insulation initiatives, hearing impairment, or other coping strategies. Furthermore, disentangling the effects of daytime and nighttime noise exposure remains challenging for most epidemiological studies given that the correlation between daytime and nighttime noise is close to one (Halonen et al. 2015; Héritier et al. 2018; Sørensen et al. 2014), which is also the case for the present study. However, road traffic noise at the least exposed façade is likely to represent the outdoor exposure at the bedroom given that people normally prefer to sleep in a quiet room and, thus, is closer to the actual nighttime exposure. Such exposure misclassification would likely be nondifferential with regard to case status and would hence drive the risk estimates toward the null, and we cannot rule out that this may have masked associations in our data.

Last, we cannot rule out residual confounding because we did not query participants on sleep quality nor did we assess variables such as mental stress, social isolation, or job strain. However, we adjusted for many important risk factors for hypertension and, therefore, residual confounding likely played a minor role in the present study.

Despite a growing body of literature regarding traffic noise and hypertension, it remains difficult to draw conclusions regarding causality because the majority of studies are of cross-sectional design (van Kempen et al. 2018). In general, cross-sectional studies have found associations for road traffic noise and prevalent hypertension (Babisch et al. 2014; Jarup et al. 2008; van Kempen et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2019; Bluhm et al. 2007; van Kempen and Babisch 2012), although not consistently (Klompmaker et al. 2019), whereas cohort studies investigating incident hypertension found no associations (Carey et al. 2016; Pyko et al. 2018; Sørensen et al. 2011). Our findings are in line with Swedish and British cohort studies that also reported no association between road traffic noise and incident hypertension, identified using combinations of measured blood pressure, self-reported hypertension or medication use, and hospital records (Carey et al. 2016; Pyko et al. 2018). In a meta-analysis of seven European cohorts, Fuks et al. (2017) found that road traffic noise was weakly associated with the incidence of self-reported hypertension as well as with self-reported intake of blood pressure–lowering medication and that this association seemed to be attenuated by adjustment for . Road traffic noise and air pollution are correlated, reflecting that road traffic is a source of both exposures, and such collinearity of predictors can result in unreliable and unstable estimates of regression coefficients (Vatcheva et al. 2016). For example, including 10-y mean exposure to resulted in a change in the risk estimate for 10-y exposure to road traffic noise at the most exposed façade from 0.999 to 1.037. It is difficult to biologically explain how adjustment for air pollution could unmask such an association; therefore, issues related to the noise–air pollution collinearity are more likely. Thus, it is important that similar studies calculate estimates both before and after mutual adjustment for noise–air pollution to limit misinterpretation of the results.

Our study provided weak indications that some subpopulations may be more susceptible to the effects of road traffic noise in relation to filled prescriptions for AHT. We found indications of associations between noise at the least exposed façade and risk of filled prescriptions for AHT among smokers and obese individuals. These are all risk factors for developing hypertension (Hall et al. 2015; Tedesco et al. 2001; Virdis et al. 2010), and it could suggest that these participants constitute a more susceptible population with regard to cardiovascular effects of exposure to road traffic noise. Effects of noise exposure on sleep duration and sleep fragmentation are believed to be important on the pathway from exposure to CVD (Münzel et al. 2014). Both sleep fragmentation and reduced sleep duration have been associated with endothelial dysfunction, decreased arterial compliance, atherosclerotic alterations, and hypertension (Münzel et al. 2018b; Recio et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2012). Because people often choose to have their bedroom away from a noisy road, exposure at the least exposed façade could potentially be more relevant in relation to risk of hypertension than exposure at the most exposed façade, through the disturbance of sleep.

The lack of association between road traffic noise and AHT in our study is in contrast to results from experimental studies with exposure to transportation noise in controlled settings, which rather consistently finds exposure to transportation noise to result in increased blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction (Foraster et al. 2017; Schmidt et al. 2013, 2015). One explanation for this discrepancy might be that participants exposed to noise during a longer time habituate; thus, it is possible that the physiological reactions observed in experimental studies are higher during the first nights compared with later ones (Basner et al. 2011). However, other studies have shown that habituation is not complete given that individuals continue to react after several years of noise exposure and that risk increases with exposure duration (Basner and McGuire 2018). In addition, epidemiological studies have consistently shown that road traffic noise results in a higher risk of myocardial infarction and potentially other CVDs for which hypertension is a principal risk factor (van Kempen et al. 2018). Therefore, we cannot rule out that filled prescriptions for AHT may be a relatively imprecise proxy for hypertension and that actual measurements of systolic and diastolic blood pressure are necessary to measure an effect of noise on hypertension.

With regard to generalizability, the Diet, Cancer and Health cohort response was 35%, and participants were more often older, female, and had higher socioeconomic status and a lower mortality rate compared with nonparticipants (Larsen et al. 2012; Tjønneland et al. 2007). Moreover, participants were recruited from two urban areas of Denmark, Copenhagen and Aarhus, where road traffic noise exposure is larger compared with other parts of Denmark. If nonparticipation was related to higher levels of road traffic noise and simultaneously to poorer health compared with participants, we may have underestimated the true effect in the source population. Although these differences may limit the generalizability of our findings to the entire Danish population, they are unlikely to have affected their internal validity.

In conclusion, we found no overall association between long-term exposure to road traffic noise and filled prescriptions for AHT. However, our results provided a weak indication that road traffic noise at the quiet side of the residence may increase risk among smokers and obese individuals.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Independent Research Fund Denmark (DFF; grant 7016-00036B).

References

- Andersen B, Bendtsen H. 2002. Beregning af vejtrafikstøj—en manual. [In Danish.] Rapport 240. Copenhagen, Denmark: Miljøstyrelsen og Vejdirektoratet; https://referencelaboratoriet.dk/metodeliste/2002_Vejdirektoratet_Beregning_af_vejstoej_en_manual_240.pdf [accessed 2 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Babisch W. 2003. Stress hormones in the research on cardiovascular effects of noise. Noise Health 5(18):1–11, PMID: 12631430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babisch W. 2006. Transportation noise and cardiovascular risk: updated review and synthesis of epidemiological studies indicate that the evidence has increased. Noise Health 8(30):1–29, PMID: 17513892, 10.4103/1463-1741.32464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babisch W. 2014. Updated exposure-response relationship between road traffic noise and coronary heart diseases: a meta-analysis. Noise Health 16(68):1–9, PMID: 24583674, 10.4103/1463-1741.127847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babisch W, Wölke G, Heinrich J, Straff W. 2014. Road traffic noise and hypertension—accounting for the location of rooms. Environ Res 133:380–387, PMID: 24952459, 10.1016/j.envres.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basner M, McGuire S. 2018. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: a systematic review on environmental noise and effects on sleep. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(3):519, PMID: 29538344, 10.3390/ijerph15030519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basner M, Müller U, Elmenhorst EM. 2011. Single and combined effects of air, road, and rail traffic noise on sleep and recuperation. Sleep 34(1):11–23, PMID: 21203365, 10.1093/sleep/34.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beelen R, Stafoggia M, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Andersen ZJ, Xun WW, Katsouyanni K, et al. 2014. Long-term exposure to air pollution and cardiovascular mortality: an analysis of 22 European cohorts. Epidemiology 25(3):368–378, PMID: 24589872, 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendtsen H. 1999. The Nordic prediction method for road traffic noise. Sci Total Environ 235(1–3):331–338, 10.1016/S0048-9697(99)00216-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bluhm GL, Berglind N, Nordling E, Rosenlund M. 2007. Road traffic noise and hypertension. Occup Environ Med 64(2):122–126, 10.1136/oem.2005.025866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodin T, Björk J, Ardö J, Albin M. 2015. Annoyance, sleep and concentration problems due to combined traffic noise and the benefit of quiet side. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(2):1612–1628, PMID: 25642690, 10.3390/ijerph120201612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Christensen JH, Frohn LM, Berkowicz R. 2003. Air pollution forecasting from regional to urban street scale––implementation and validation for two cities in Denmark. Phys Chem Earth 28(8):335–344, 10.1016/S1474-7065(03)00054-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Silver JD, Frohn LM, Geels C, Gross A, Hansen AB, et al. 2012. An integrated model study for Europe and North America using the Danish Eulerian Hemispheric Model with focus on intercontinental transport of air pollution. Atmos Environ 53:156–176, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2012.01.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey IM, Anderson HR, Atkinson RW, Beevers S, Cook DG, Dajnak D, et al. 2016. Traffic pollution and the incidence of cardiorespiratory outcomes in an adult cohort in London. Occup Environ Med 73(12):849–856, PMID: 27343184, 10.1136/oemed-2015-103531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen B, Kristensen JK, Marcussen MM, Borch-Johnsen K. 2011. The National Diabetes Register. Scand J Public Health 39(suppl 7):58–61, PMID: 21775353, 10.1177/1403494811404278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TY, Hwang BF, Liu CS, Chen RY, Wang VS, Bao BY, et al. 2013. Occupational noise exposure and incident hypertension in men: a prospective cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 177(8):818–825, PMID: 23470795, 10.1093/aje/kws300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimakopoulou K, Koutentakis K, Papageorgiou I, Kasdagli MI, Haralabidis AS, Sourtzi P, et al. 2017. Is aircraft noise exposure associated with cardiovascular disease and hypertension? Results from a cohort study in Athens, Greece. Occup Environ Med 74(11):830–837, PMID: 28611191, 10.1136/oemed-2016-104180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dratva J, Phuleria HC, Foraster M, Gaspoz JM, Keidel D, Künzli N, et al. 2012. Transportation noise and blood pressure in a population-based sample of adults. Environ Health Perspect 120(1):50–55, PMID: 21885382, 10.1289/ehp.1103448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzhambov AM, Dimitrova DD. 2018. Residential road traffic noise as a risk factor for hypertension in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of analytic studies published in the period 2011–2017. Environ Pollut 240:306–318, PMID: 29751327, 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.04.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foraster M, Eze IC, Schaffner E, Vienneau D, Héritier H, Endes S, et al. 2017. Exposure to road, railway, and aircraft noise and arterial stiffness in the SAPALDIA study: annual average noise levels and temporal noise characteristics. Environ Health Perspect 125(9):097004, PMID: 28934719, 10.1289/EHP1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuks KB, Weinmayr G, Basagaña X, Gruzieva O, Hampel R, Oftedal B, et al. 2017. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and traffic noise and incident hypertension in seven cohorts of the European Study of Cohorts for Air Pollution Effects (ESCAPE). Eur Heart J 38(13):983–990, PMID: 28417138, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Risk Factor Collaborators. 2017. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 390(10100):1345–1422, PMID: 28919119, 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenland S. 1995. Dose–response and trend analysis in epidemiology: alternatives to categorical analysis. Epidemiology 6(4):356–365, PMID: 7548341, 10.1097/00001648-199507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. 2015. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res 116(6):991–1006, PMID: 25767285, 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen JI, Hansell AL, Gulliver J, Morley D, Blangiardo M, Fecht D, et al. 2015. Road traffic noise is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and all-cause mortality in London. Eur Heart J 36(39):2653–2661, PMID: 26104392, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Héritier H, Vienneau D, Foraster M, Eze IC, Schaffner E, Thiesse L, et al. 2018. Diurnal variability of transportation noise exposure and cardiovascular mortality: a nationwide cohort study from Switzerland. Int J Hyg Environ Health 221(3):556–563, PMID: 29482991, 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog J, Schmidt FP, Hahad O, Mahmoudpour SH, Mangold AK, Garcia Andreo P, et al. 2019. Acute exposure to nocturnal train noise induces endothelial dysfunction and pro-thromboinflammatory changes of the plasma proteome in healthy subjects. Basic Res Cardiol 114(6):46, PMID: 31664594, 10.1007/s00395-019-0753-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hvidtfeldt UA, Ketzel M, Sørensen M, Hertel O, Khan J, Brandt J, et al. 2018. Evaluation of the Danish AirGIS air pollution modeling system against measured concentrations of PM2.5, PM10, and black carbon. Environ Epidemiol 2(2):e014, 10.1097/EE9.0000000000000014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarup L, Babisch W, Houthuijs D, Pershagen G, Katsouyanni K, Cadum E, et al. 2008. Hypertension and exposure to noise near airports: the HYENA study. Environ Health Perspect 116(3):329–333, PMID: 18335099, 10.1289/ehp.10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SS, Ketzel M, Becker T, Christensen J, Brandt J, Plejdrup M, et al. 2017. High resolution multi-scale air quality modelling for all streets in Denmark. Transp Res D Transp Environ 52(pt A):322–339, 10.1016/j.trd.2017.02.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SS, Hvidberg M, Pedersen J, Storm L, Stausgaard L, Becker L, et al. 2009. GIS-baseret national vej- og trafikdatabase 1960–2005. [In Danish.] Faglig rapport fra DMU nr. 678. Aarhus, Denmark: Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Aarhus Universitet; https://www2.dmu.dk/Pub/FR678.pdf [accessed 2 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen SS, Plejdrup MS, Hillig K. 2019. GIS-Based National Road and Traffic Database 1960–2020. Technical report no. 151. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University, Danish Centre for Environment and Energy (DCE) http://dce2.au.dk/pub/TR151.pdf [accessed 2 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Ketzel M, Berkowicz R, Hvidberg M, Jensen SS, Raaschou-Nielsen O. 2011. Evaluation of AirGIS: a GIS-based air pollution and human exposure modelling system. Int J Environ Pollut 47(1–4):226–238, 10.1504/IJEP.2011.047337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ketzel M, Jensen SS, Brandt J, Ellermann T, Olesen HR, Berkowicz R, et al. 2013. Evaluation of the street pollution model OSPM for measurements at 12 streets stations using a newly developed and freely available evaluation tool. J Civil Environ Eng 1(S1):004, 10.4172/2165-784X.S1-004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan J, Kakosimos K, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Brandt J, Jensen SS, Ellermann T, et al. 2019. Development and performance evaluation of new AirGIS–a GIS based air pollution and human exposure modelling system. Atmos Environ 198:102–121, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.10.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. 2011. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 39(suppl 7):38–41, PMID: 21775349, 10.1177/1403494810394717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klompmaker JO, Janssen NAH, Bloemsma LD, Gehring U, Wijga AH, van den Brink C, et al. 2019. Associations of combined exposures to surrounding green, air pollution, and road traffic noise with cardiometabolic diseases. Environ Health Perspect 127(8):87003, PMID: 31393793, 10.1289/EHP3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronborg CN, Hallas J, Jacobsen IA. 2009. Prevalence, awareness, and control of arterial hypertension in Denmark. J Am Soc Hypertension 3(1):19–24.e2, PMID: 20409941, 10.1016/j.jash.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SB, Dalton SO, Schüz J, Christensen J, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, et al. 2012. Mortality among participants and non-participants in a prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol 27(11):837–845, PMID: 23070658, 10.1007/s10654-012-9739-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PJ, Park SH, Jeong JH, Choung T, Kim KY. 2019. Association between transportation noise and blood pressure in adults living in multi-storey residential buildings. Environ Int 132:105101, PMID: 31434052, 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long AN, Dagogo-Jack S. 2011. Comorbidities of diabetes and hypertension: mechanisms and approach to target organ protection. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 13(4):244–251, PMID: 21466619, 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. 2012. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859):2095–2128, PMID: 23245604, 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. 2011. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 39(suppl 7):30–33, PMID: 21775347, 10.1177/1403494811401482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miedema HME, Vos H. 2007. Associations between self-reported sleep disturbance and environmental noise based on reanalyses of pooled data from 24 studies. Behav Sleep Med 5(1):1–20, PMID: 17313321, 10.1207/s15402010bsm0501_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Gori T, Babisch W, Basner M. 2014. Cardiovascular effects of environmental noise exposure. Eur Heart J 35(13):829–836, PMID: 24616334, 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Schmidt FP, Steven S, Herzog J, Daiber A, Sørensen M. 2018a. Environmental noise and the cardiovascular system. J Am Coll Cardiol 71(6):688–697, PMID: 29420965, 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel T, Sørensen M, Schmidt F, Schmidt E, Steven S, Kröller-Schön S, et al. 2018b. The adverse effects of environmental noise exposure on oxidative stress and cardiovascular risk. Antioxid Redox Signal 28(9):873–908, PMID: 29350061, 10.1089/ars.2017.7118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CB. 2011. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health 39(suppl 7):22–25, PMID: 21775345, 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulsen AH, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Peña A, Hahmann AN, Nordsborg RB, Ketzel M, et al. 2018. Long-term exposure to wind turbine noise and redemption of antihypertensive medication: a nationwide cohort study. Environ Int 121(pt 1):207–215, PMID: 30216773, 10.1016/j.envint.2018.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyko A, Lind T, Mitkovskaya N, Ögren M, Östenson CG, Wallas A, et al. 2018. Transportation noise and incidence of hypertension. Int J Hyg Environ Health 221(8):1133–1141, PMID: 30078646, 10.1016/j.ijheh.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recio A, Linares C, Banegas JR, Díaz J. 2016. Road traffic noise effects on cardiovascular, respiratory, and metabolic health: an integrative model of biological mechanisms. Environ Res 146:359–370, PMID: 26803214, 10.1016/j.envres.2015.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt FP, Basner M, Kröger G, Weck S, Schnorbus B, Muttray A, et al. 2013. Effect of nighttime aircraft noise exposure on endothelial function and stress hormone release in healthy adults. Eur Heart J 34(45):3508–3514, PMID: 23821397, 10.1093/eurheartj/eht269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt F, Kolle K, Kreuder K, Schnorbus B, Wild P, Hechtner M, et al. 2015. Nighttime aircraft noise impairs endothelial function and increases blood pressure in patients with or at high risk for coronary artery disease. Clin Res Cardiol 104(1):23–30, PMID: 25145323, 10.1007/s00392-014-0751-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selander J, Bluhm G, Theorell T, Pershagen G, Babisch W, Seiffert I, et al. 2009. Saliva cortisol and exposure to aircraft noise in six European countries. Environ Health Perspect 117(11):1713–1717, PMID: 20049122, 10.1289/ehp.0900933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen M, Hoffmann B, Hvidberg M, Ketzel M, Jensen SS, Andersen ZJ, et al. 2012. Long-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution associated with blood pressure and self-reported hypertension in a Danish cohort. Environ Health Perspect 120(3):418–424, PMID: 22214647, 10.1289/ehp.1103631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen M, Hvidberg M, Hoffmann B, Andersen ZJ, Nordsborg RB, Lillelund KG, et al. 2011. Exposure to road traffic and railway noise and associations with blood pressure and self-reported hypertension: a cohort study. Environ Health 10:92, PMID: 22034939, 10.1186/1476-069X-10-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen M, Ketzel M, Overvad K, Tjønneland A, Raaschou-Nielsen O. 2014. Exposure to road traffic and railway noise and postmenopausal breast cancer: a cohort study. Int J Cancer 134(11):2691–2698, PMID: 24338235, 10.1002/ijc.28592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokholm ZA, Bonde JP, Christensen KL, Hansen AM, Kolstad HA. 2013. Occupational noise exposure and the risk of hypertension. Epidemiology 24(1):135–142, PMID: 23191997, 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826b7f76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco MA, Di Salvo G, Caputo S, Natale F, Ratti G, Iarussi D, et al. 2001. Educational level and hypertension: how socioeconomic differences condition health care. J Hum Hypertens 15(10):727–731, PMID: 11607804, 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thacher JD, Poulsen AH, Raaschou-Nielsen O, Jensen A, Hillig K, Roswall N, et al. 2020. High-resolution assessment of road traffic noise exposure in Denmark. Environ Res 182:109051, PMID: 31896468, 10.1016/j.envres.2019.109051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Therneau T. 2017. Spline terms in a Cox model. https://web.mit.edu/-r/current/lib/R/library/survival/doc/splines.pdf [accessed 30 October 2018].

- Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Boll K, Stripp C, Christensen J, Engholm G, et al. 2007. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: a population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women in Denmark. Scand J Public Health 35(4):432–441, PMID: 17786808, 10.1080/14034940601047986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Haraldsdóttir J, Bang S, Ewertz M, Jensen OM. 1991. Validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire developed in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol 20(4):906–912, PMID: 1800429, 10.1093/ije/20.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen E, Babisch W. 2012. The quantitative relationship between road traffic noise and hypertension: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens 30(6):1075–1086, PMID: 22473017, 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328352ac54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen E, Casas M, Pershagen G, Foraster M. 2018. WHO environmental noise guidelines for the European region: a systematic review on environmental noise and cardiovascular and metabolic effects: a summary. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(2):379, PMID: 29470452, 10.3390/ijerph15020379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen EEMM, Kruize H, Boshuizen HC, Ameling CB, Staatsen BAM, de Hollander AEM. 2002. The association between noise exposure and blood pressure and ischemic heart disease: a meta-analysis. Environ Health Perspect 110(3):307–317, PMID: 11882483, 10.1289/ehp.02110307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vatcheva KP, Lee M, McCormick JB, Rahbar MH. 2016. Multicollinearity in regression analyses conducted in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology 6(2):227, PMID: 27274911, 10.4172/2161-1165.1000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura HO, Lavie CJ. 2016. Impact of comorbidities in hypertension. Curr Opin Cardiol 31(4):374–375, PMID: 27205884, 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vienneau D, Schindler C, Perez L, Probst-Hensch N, Röösli M. 2015. The relationship between transportation noise exposure and ischemic heart disease: a meta-analysis. Environ Res 138:372–380, PMID: 25769126, 10.1016/j.envres.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdis A, Giannarelli C, Neves MF, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L. 2010. Cigarette smoking and hypertension. Curr Pharm Des 16(23):2518–2525, PMID: 20550499, 10.2174/138161210792062920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Xi B, Liu M, Zhang Y, Fu M. 2012. Short sleep duration is associated with hypertension risk among adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res 35(10):1012–1018, PMID: 22763475, 10.1038/hr.2012.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 1966. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 8th Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2013. A Global Brief on Hypertension—Silent Killer, Global Public Health Crisis. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/79059/WHO_DCO_WHD_2013.2_eng.pdf;jsessionid=C1467B16219DD90F9411B4E0EFF30554?sequence=1 [accessed 2 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. 2016. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en [accessed 2 May 2020].

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. 2018. Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/383921/noise-guidelines-eng.pdf [accessed 2 May 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- Zeeb H, Hegewald J, Schubert M, Wagner M, Dröge P, Swart E, et al. 2017. Traffic noise and hypertension—results from a large case–control study. Environ Res 157:110–117, PMID: 28554004, 10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.