Abstract

Objectives:

Despite the interest in technology-enhanced prevention interventions for suicidality, there is minimal peer-reviewed research on conversations of text-message hotlines. This large-scale study explored distinct classes of suicidal Crisis Text Line users based on their presenting psychosocial issues across frequency of hotline use and conversation number.

Methods:

Data included 153,514 conversations from 122,909 individuals collected by Crisis Text Line from 2013 to 2017. Analyses were restricted to conversations from users who mentioned current or previous suicidality and excluded texters discussing a third party. Latent class analysis was used to identify distinct classes of texters based on crisis counselor-assigned tags of conversations, across conversation number of three frequency-of-use subgroups: one-time, two-time or >=three-time texters.

Results:

Three classes emerged in all subsamples. The largest class, “Lower Distress,” had the lowest prevalence of all issues. The second largest class, “Anxious Distress,” had the highest prevalence of anxiety or stress and elevated depression. The smallest group was the “Relational Distress” class. These texters had the highest prevalence of depression and self-harm, and higher probability of endorsing relational indicators.

Conclusions:

Psychological and relational issues mostly distinguished the three classes. The findings suggest that, despite differing frequency of hotline usage, most suicidal texters are endorsing similar issues, and these issues do not seem to vary across conversations. Yet, there appears to be distinct subgroups of texters based on presenting issues, which may inform how crisis counselors tailor strategies for both low- and high-volume texters.

Introduction

Suicide remains a leading cause of death in the United States (U.S.) and suicide rates have risen in nearly every state from 1999 to 2016 (1). Experiencing suicidal thoughts and attempting suicide is also pervasive across the U.S. population. In 2016, 9.8 million adults (ages 18 years and older) reported having serious thoughts of killing themselves, and 1.3 million adults reported attempting suicide during the past twelve months (2).

Regarding this public health crisis, it is important to link suicidal persons to accessible and immediate resources. Since the second half of the twentieth century, suicide hotlines have played an important role in U.S. suicide prevention efforts by de-escalating persons in crisis and referring them to community-based resources (3–5). In 1999, the National Hopeline Network became the first national suicide hotline (6). Subsequently, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL) was launched in 2005 and is currently the U.S.’s largest suicide hotline (7). Calls are redirected to local call centers, where volunteer crisis counselors provide crisis interventions and service referrals (8). The NSPL received 12 million calls from 2005 to 2017 and expects to receive the same number of calls within the next four years (7). This high call volume emphasizes the role of empirical research in understanding hotline users.

Research indicates that commonly mentioned problems by users of U.S.-based suicide hotlines include mental and physical health problems, financial instability, relationship problems, and housing problems (3,9). These psychosocial issues correspond with the contributing factors identified by the CDC for suicide among individuals with and without mental health diagnoses (10). Yet, studies often include samples from select call centers and do not report types of issues across the number of calls by users (3,9), even though repeated callers account for most hotline calls (11). This obscures potential differences and severity of caller issues by varying frequency of usage. Also, available research does not measure how the issues of repeat callers may change by conversation (11–13). Since repeat and suicidal callers require great amounts of hotline resources (7,12), it is important to identify these callers’ issues as a first step to inform crisis counselling interventions (13).

Hotlines utilize new technology in an effort to increase help-seeking among persons who wish to remain anonymous or want to use different modalities (14,15). Crisis Text Line is a text-based platform supporting a network of crisis support organizations in effort to increase help-seeking for distressed individuals. This free hotline can be accessed via text message, either by phone or Facebook messenger. “Texters” send a text message to the help number and are then connected to a crisis counselor based at one of the network’s crisis centers. The service was originally based in the U.S. and has now broadened its reach to Canada and the United Kingdom.

The demographics of the hotline’s texters are diverse. Approximately 75% of users are under 25 years old (16). Six percent of texters identify as Native American and 19% identify as Latinx/Hispanic (16) – two ethnic groups that have been traditionally less likely to seek help via phone hotlines (17,18). Additionally, 20% of the hotline’s user volume comes from the 10% lowest-income zip codes in the U.S. (16).

Texters can decide to have their anonymous conversations scrubbed from the hotline’s database. Texter data may inform literature on hotline services and advise training and interventions conducted by crisis counselors. As the hotline uses a machine learning algorithm to help high-risk texters first (i.e. suicidal texters) (19), it is imperative that the service and crisis counselors understand the needs and issues of these texters.

Considering the interest in technology-enhanced crisis hotlines (8) and the use of text messages in suicide attempt prevention (20), more peer-reviewed studies on large-scale conversations of text-message hotlines are needed (21–23). Since research suggests that suicidal individuals are often repeated users of text-based hotlines (22), this study aimed to increase knowledge by exploring distinct classes of suicidal texters by frequency of Crisis Text Line use and conversation number. Usage frequency highlights differences between individuals who have potentially acute versus ongoing issues, whereas conversation number among repeated texters allows insight into whether latent subgroups change by interaction with the hotline. Identifying subgroups of texters and their issues may inform text-message hotlines on how to communicate with suicidal texters and alleviate crises (11, 24, 25).

Methods

The original dataset included 211,258 Crisis Text Line conversations in which users mentioned current or previous suicidality from 2013 to 2017. Data scientists determined suicidality through a word search of all conversations approved for research purposes during the hotline’s initial years of service. Data scientists queried the message-level data using machine learning techniques to find all conversations that included associated terms and word combinations (i.e. phrases that expressed previous or current suicidality, such as “overdose”). The machine learning model was trained to predict suicide risk by reading variability in text messages and understanding context (19). The model can identify 86% of people at severe imminent risk for suicide in their first conversations. Additional queries ensured that all selected conversations mentioned phrases related to suicide and that the hotline users were engaged in actual conversations with crisis counselors rather than “dropped” or incomplete conversations.

Frequency/Conversation Subsamples

All conversations were from the U.S.-based branch of the hotline. For this analysis, subsamples were created based on the users’ frequency (i.e., total number of text conversations from the same phone number) of accessing the service and conversation number (for frequent texters). Cases with a third-party issue tag were removed from the sample (n=5,690), as this indicated that the hotline user was seeking advice for another person, rather than for themselves; therefore, the suicidal person was not participating in the conversation. Each texter received a unique number upon initial contact with the hotline and the frequency of the texter identification number within the dataset indicated if a texter had called once, twice, or three or more times. One-time users included 92,304 participants, comprising 44.9% of the full sample’s conversations. Two-time users (n=15,999) contributed 31,998 conversations (15.6%). Texters contacting the hotline three or more times (n=14,606) contributed 81,266 conversations (39.5%), but only first and last conversation was included in this analysis in order to evaluate whether texter issues were different between their initial contact with the hotline and their final conversation. The final analytic sample comprised of 153,514 conversations from 122,909 individuals.

This study was approved by the Internal Review Boards from the respected universities as exempt from human subject research. The dataset did not include any identifying information of the texters or crisis counselors (e.g. names or specific locations). Access to the aggregate-level texter data was granted by the hotline as part of their initial data enclave program (26).

Measures

Psychosocial issues.

Indicators of psychosocial issues related to four domains: psychological health, relational life, abuse, and environmental stressors. Crisis counselors “tagged” or reported psychosocial issues at the completion of each conversation based on its content. Crisis counselors are volunteers who have completed 34 hours of supervised training and have been vetted by the hotline to respond to and document calls. Crisis counselors selected from a list of 35 issue tags that had been established by the hotline. Seven tags were excluded from our analysis as they did not inform the latent construct of psychosocial issues, were redundant for our sample (i.e. suicidal ideation), and had been identified by the hotline’s research scientists as highly biased: suicidal ideation, third-party caller, medication issues, none, other, psychiatric hospitalization, problems with therapist/psychiatrist. Twenty-eight issues were selected to measure the psychosocial issue construct: seven psychological health (depression, self-harm, anxiety, mental health issues, stress, eating disorders, substance abuse); seven relational (family, friends, relationships, bereavement, isolation, bullying, LGBTQ); five abuse (physical, sexual, emotional, domestic violence, sexual assault); and nine environmental (medical, financial, work, educational testing, school, military, homelessness, homicide, election) tags. Tagging was based on the discretion of the crisis counselor. Demographic variables were excluded from the analysis due to high amount of missing data (approximately 92%). Missing or incomplete caller/texter demographic data is not uncommon to hotline research (11,27,28), as it is an anonymous crisis service. Yet, our amount of missing data does exceed that of other studies (with values ranging from approximately 1 to 64%).

Analysis

The five frequency/conversation subsamples were described according to the 28 issue tags informing the latent construct. To facilitate theoretical interpretation of the tags and our findings, we categorized tags into one of four broad issue domains: psychological, relational, abuse, and environmental. We then used latent class analysis (LCA) (29,30) with an expectation-maximum algorithm to classify texters into similar subpopulations or “classes” based on their psychosocial issues as tagged by the crisis counselors in their first and last conversation by frequency/conversation subsample. The categorization of psychosocial issue tags did not influence modeling of the latent classes, as all 28 issues were included in the analyses.

LCA is an appropriate statistical technique for our study, as it identifies two or more unobserved subgroups of participants based on covariation between multiple observed indicator variables (31,32). Class enumeration occurred within each frequency/conversation subsample, guided by fit indices and considerations of parsimony (32). Within each subsample, we implemented one- to five-class LCA models and evaluated the following fit statistics: Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample size adjusted BIC (aBIC), Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR) (33). Starting with a one-class model (the baseline comparison for all subsequent models) enumeration continued until empirical under-identification or convergence problems signaled that the inclusion of additional classes was not needed or feasible (see supplementary table for additional fit statistics). Entropy was also estimated to evaluate quality of class separation (34), with values approaching 1 indicating clearer distinction between classes based on the indicators (35). Following model selection, class-specific probabilities of having an item tagged were graphically displayed within each frequency/conversation subsample. Analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 8.1 (36).

Results

Table 1 displays the prevalence of the 28 psychosocial issue tags for each frequency/conversation subsample. Across the overall sample, depression (n=64,323; 41.9%), and family concerns (n=38,425; 25%) were the two most frequent issues. Among the one-time users, depression (n=38, 948; 42.2%) and family concerns (n=24,460; 26.5%) were also the two most frequent issues. Among the two-time users, 45 percent (n=7,198) described depression as an issue in their first conversation versus 37.7 percent (n=6,031) in the second conversation. Family concerns were again a frequent issue in their first (n=4,082; 25.5%) and second conversations (n=3,499; 21.9%). Among users who contacted CTL 3 or more times, depression (n=6,968, 47.7%) and self-harm (n=3,752, 25.7%) were the most frequent issues in the first conversation; depression (n=5,178, 35.5%) and family concerns (n=2,805, 19.2%) were the most frequent issues in the second conversation.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of psychosocial issue tags among suicidal texters, by frequency/conversation subsamplea

| Overall Sample | 1-Time Callers | 2-Time Callers | 2-Time Callers | 3+ Time Callers | 3+ Time Callers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=153,514 | N=92,304 | N=15,999 | N=15,999 | N=14,606 | N=14,606 | |||||||

| Single Conv. | 1st Conv. | 2nd Conv. | 1st Conv. | 2nd Conv. | ||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Psychological Concerns | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 64,323 | 41.9% | 38948 | 42.2% | 7198 | 45.0% | 6031 | 37.7% | 6968 | 47.7% | 5178 | 35.5% |

| Self-Harm | 25,367 | 16.5% | 13124 | 14.2% | 3244 | 20.3% | 2577 | 16.1% | 3752 | 25.7% | 2670 | 18.3% |

| Anxiety | 24,238 | 15.8% | 15016 | 16.3% | 2672 | 16.7% | 2134 | 13.3% | 2617 | 17.9% | 1799 | 12.3% |

| Mental | 10,080 | 6.6% | 5977 | 6.5% | 1113 | 7.0% | 1014 | 6.3% | 1031 | 7.1% | 945 | 6.5% |

| Stress | 24,970 | 16.3% | 15656 | 17.0% | 2740 | 17.1% | 2113 | 13.2% | 2783 | 19.1% | 1678 | 11.5% |

| Eating Disorder | 3,815 | 2.5% | 2078 | 2.3% | 447 | 2.8% | 369 | 2.3% | 533 | 3.6% | 388 | 2.7% |

| Substance Abuse | 4,458 | 2.9% | 2930 | 3.2% | 430 | 2.7% | 396 | 2.5% | 343 | 2.3% | 359 | 2.5% |

| Relational Concerns | ||||||||||||

| Family | 38,425 | 25.0% | 24460 | 26.5% | 4082 | 25.5% | 3499 | 21.9% | 3579 | 24.5% | 2805 | 19.2% |

| Friends | 15,949 | 10.4% | 9578 | 10.4% | 1798 | 11.2% | 1565 | 9.8% | 1694 | 11.6% | 1314 | 9.0% |

| Relationships | 25,097 | 16.3% | 16700 | 18.1% | 2532 | 15.8% | 2319 | 14.5% | 1901 | 13.0% | 1645 | 11.3% |

| Bereavement | 4,528 | 2.9% | 2968 | 3.2% | 450 | 2.8% | 371 | 2.3% | 449 | 3.1% | 290 | 2.0% |

| Isolated | 20,166 | 13.1% | 12222 | 13.2% | 2271 | 14.2% | 1901 | 11.9% | 2181 | 14.9% | 1591 | 10.9% |

| Bullying | 6,111 | 4.0% | 3401 | 3.7% | 844 | 5.3% | 613 | 3.8% | 804 | 5.5% | 449 | 3.1% |

| LGBTQ | 4,101 | 2.7% | 2247 | 2.4% | 536 | 3.4% | 379 | 2.4% | 587 | 4.0% | 352 | 2.4% |

| Abuse | ||||||||||||

| Physical | 2,109 | 1.4% | 1221 | 1.3% | 266 | 1.7% | 158 | 1.0% | 332 | 2.3% | 132 | 0.9% |

| Sexual | 4,188 | 2.7% | 2371 | 2.6% | 450 | 2.8% | 402 | 2.5% | 573 | 3.9% | 392 | 2.7% |

| Emotional | 2,733 | 1.8% | 1782 | 1.9% | 260 | 1.6% | 272 | 1.7% | 189 | 1.3% | 230 | 1.6% |

| Domestic | ||||||||||||

| Violence | 637 | 0.4% | 448 | 0.5% | 48 | 0.3% | 57 | 0.4% | 44 | 0.3% | 40 | 0.3% |

| Sexual Assault | 977 | 0.6% | 576 | 0.6% | 88 | 0.6% | 99 | 0.6% | 71 | 0.5% | 143 | 1.0% |

| Environmental Concerns | ||||||||||||

| Medical | 4,333 | 2.8% | 2787 | 3.0% | 426 | 2.7% | 371 | 2.3% | 424 | 2.9% | 325 | 2.2% |

| Financial | 4,317 | 2.8% | 3047 | 3.3% | 382 | 2.4% | 337 | 2.1% | 287 | 2.0% | 264 | 1.8% |

| Work | 4,027 | 2.6% | 2760 | 3.0% | 364 | 2.3% | 342 | 2.1% | 272 | 1.9% | 289 | 2.0% |

| Testing | 90 | 0.1% | 80 | 0.1% | 5 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.0% | 3 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.0% |

| School | 6,925 | 4.5% | 4123 | 4.5% | 827 | 5.2% | 685 | 4.3% | 687 | 4.7% | 603 | 4.1% |

| Military | 323 | 0.2% | 239 | 0.3% | 22 | 0.1% | 26 | 0.2% | 15 | 0.1% | 21 | 0.1% |

| Homeless | 1,165 | 0.8% | 827 | 0.9% | 79 | 0.5% | 114 | 0.7% | 67 | 0.5% | 78 | 0.5% |

| Homicide | 198 | 0.1% | 111 | 0.1% | 12 | 0.1% | 29 | 0.2% | 16 | 0.1% | 30 | 0.2% |

| Election | 390 | 0.3% | 282 | 0.3% | 32 | 0.2% | 38 | 0.2% | 22 | 0.2% | 16 | 0.1% |

Data were from n=153,514 messages to Crisis Text Line 2013–2017 (n=122,909 individuals); Conv.=conversation

Class enumeration results and fit statistics for the unconditional latent class models are presented in Table 2. Based on statistical and substantive results, a 3-class solution was chosen for each of the five frequency and conversation subgroups. Entropy (range: 0.732–0.816) indicated that the most probable class assignment was good (34).

TABLE 2.

Model fit indices for final latent class models for frequency/conversation subsamplesa

| Number of | Log Likelihood | Information Criteria | LMR Likelihood Ratio Test | Entropy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caller Type | Conversation | Classes | Free Parameters | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Statistic | p-value | ||

| One-Time | Single | 3 | 86 | −508313 | 1016798 | 1017609 | 1017336 | 6258.49 | <0.001 | 0.758 |

| Two-Time | First | 3 | 86 | −89028 | 178228 | 178888 | 178615 | 1340.22 | <0.001 | 0.776 |

| Second | 3 | 86 | −80983 | 162137 | 162798 | 162524 | 901.11 | <0.001 | 0.753 | |

| Three+ Time | First | 3 | 86 | −82756 | 165683 | 166336 | 166063 | 1436.56 | <0.001 | 0.816 |

| Last | 3 | 86 | −70912 | 141996 | 142649 | 142375 | 841.43 | 0.038 | 0.732 | |

Data were from n=153,514 messages to Crisis Text Line 2013–2017 (n=122,909 individuals); AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; aBIC, adjusted Bayesian information criterion; LMR, Lo-Mendell-Rubin

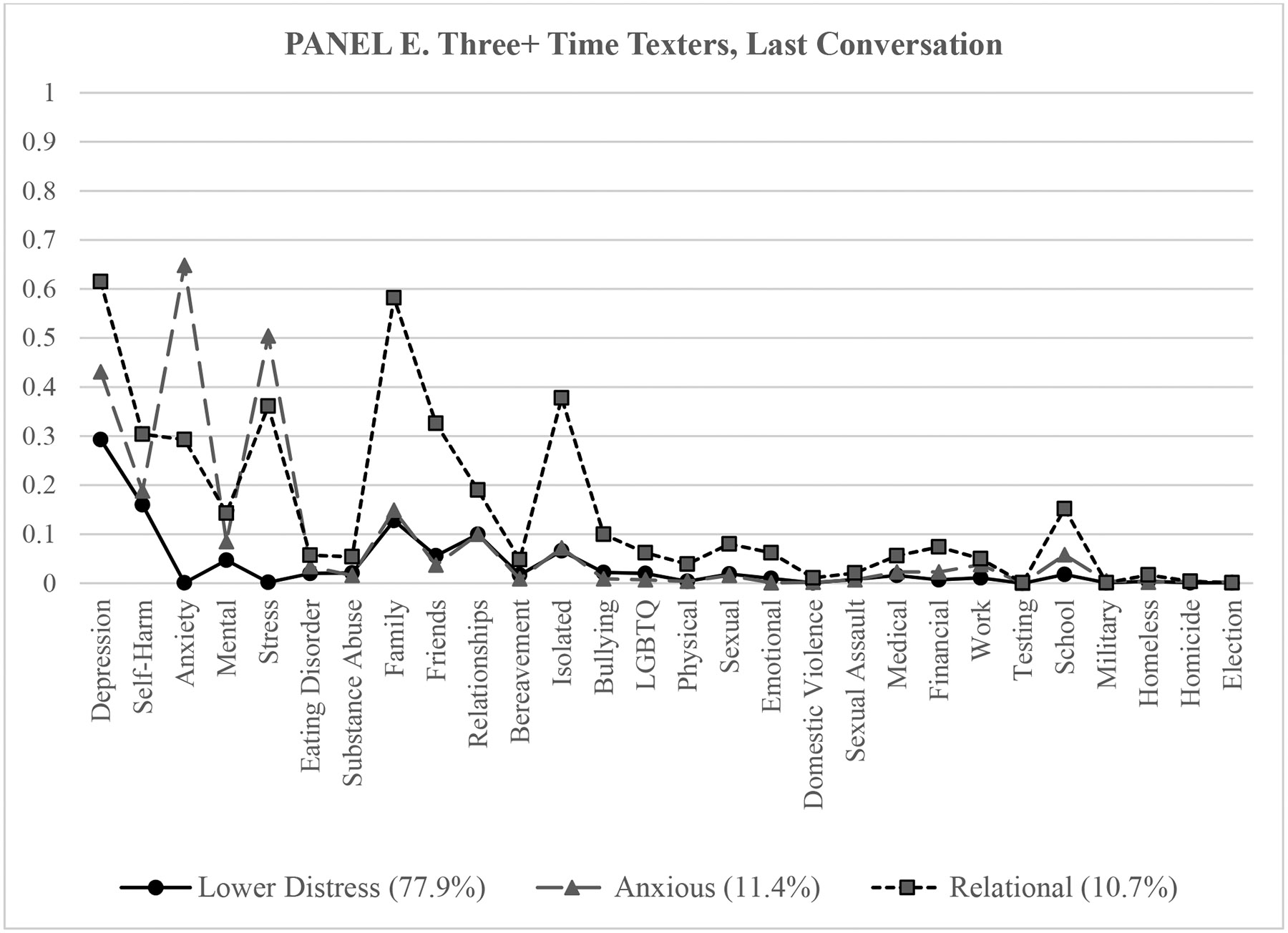

Similar classes of texters according to their psychosocial issue tags were found across all five frequency/conversation subgroups (Figure 1.A–1.E). The largest class (approximately 75% of each subsample) was named “Lower Distress”, as the prevalence of all issues, regardless of domain, were lower than the other classes. However, they still expressed non-negligible levels of depression and self-harm. Other salient issues among this class were relational in nature: pertaining to family, friends or relationships. The second largest class (11–15% of each subsample) were those with “Anxious Distress”, named due to having the highest prevalence of anxiety or stress. They also were more likely to report depression than the Lower Distress Class. Finally, the smallest group was the “Relational Distress” class (range: 7–11%). These texters were classified as having the highest prevalence of depression and self-harm. While they had elevated levels of the majority of indicators in the relational domain, the most salient were family, friends and isolation. In addition, school issues emerged as prominent concerns. These texters were classified as having medium levels of anxiety and stress as compared to the other two classes. These three classes (“lower distress”, “anxious distress”, and “relational distress”) were found in all five frequency/conversation subsamples.

FIGURE 1.

Probability of endorsing 28 psychosocial issue tags, by latent class within frequency/conversation subsamplesa

a Data were from n=153,514 messages to Crisis Text Line 2013–2017 (n=122,909 individuals).

Discussion

This large-scaled study explored distinct subgroups of psychosocial issues among suicidal texters across frequency of hotline use and conversation number subgroups in the U.S. We found three general classes of suicidal texters, which did not change greatly by frequency of hotline use or conversation number. Classes were distinguished mostly by prevalence of psychological and relational issues, as opposed to abuse and environmental issues, reported by crisis counselors during text-message interactions. While the most common subgroup across hotline use and conversation displayed fewer issues of depression and self-harm, two smaller subgroups demonstrated problems with stress, anxiety, friends, and school in addition to higher levels of depression and self-harm. Our results suggest that, despite differing frequency of hotline usage, most suicidal texters are endorsing similar issues, and these issues do not seem to vary by conversation. However, there seem to be distinct subgroups of texters based on their presenting issues, which can inform hotline strategies.

These findings support the emerging research on the psychosocial issues of suicidal users of text-message based hotlines. Sindahl et al. (22) reported that self-harm, bullying, and interpersonal problems were co-occurring issues for Danish suicidal texters. Mental health problems, issues with family or partners, and rumination were the most prominent co-occurring issues for users of the Dutch 113Online Suicide Prevent Crisis Chat Service (27). Among callers from eight local telephone hotlines in the U.S., Gould and colleagues (37) identified similar psychosocial issues, including exposure to interpersonal problems, mental health concerns, and difficulty meeting basic needs (e.g., shelter, food). More research is needed to better understand the subgroups of suicidal users of text-message hotlines across frequency of use and conversations, and how they may compare to telephone hotline users.

Our findings have implications for crisis counselor training. The results from the latent class analysis suggest that, in addition to depression, suicidal texters primarily struggle with stress and anxiety management and interpersonal relationships. Crisis counselors should be prepared to employ emotion regulation techniques to support texters until they receive community-based services. Specifically, crisis counselors should understand evidence-based coping skills suited for persons with urges to self-harm, anxiety, and interpersonal issues outside of abuse.

Crisis counselors may also tailor approaches to the three distinct classes of texters that were found in the overall sample of suicidal texters. Understanding that these subgroups exist may help crisis counselors address issues not initially presented by the texter. For example, a crisis counselor who engages a texter expressing school-related issues may also want to use open-ended questions to inquire about other issues known to be prevalent in the “Relational” class (i.e., the class with the highest probability of school issues): problems with family, friends, and feelings of isolation. As the classes present similarly across frequency/conversation subsamples, how the crisis counselor approaches the individual is not necessarily informed by a texter’s history with the hotline. In contrast to recent studies on frequent users (11–13), our findings suggest that knowing whether a texter is a repeat caller versus a one-time caller does not enhance the crisis counselor’s ability to address the psychosocial issues at hand.

To validate the tagging of texters’ psychosocial issues, the hotline may ask for texters to self-report report their most pressing issues. The storage of message-level data may provide also future opportunities to examine the validity and reliability of issues tags from conversations and to improve the accuracy of issue tagging. Such information may illuminate why suicidal texters who are tagged with similar issues display different frequencies of hotline usage and how to encourage community-based help seeking (22).

Limitations

Limitations of the study are noted. As described in the Methods section, data were collected during the hotline’s initial years of service and there is significant missing data on texter demographics (i.e., age, gender, and ethnicity). Therefore, we cannot apply the findings to specific populations. Recently, the hotline has employed strategies to reduce texter missing data regarding user demographics and user experience, such as imputing survey responses for non-respondents.

Additionally, the crisis counselors tagged texter conversations from a list of prevalent psychosocial issues, versus collecting texters’ self-reported problems. Tags were at the discretion of one crisis counselor per conversation, and inter-rater reliability could not be calculated. Research scientists regularly perform quality checks of the issue tags and have removed highly-biased tags from the list (see Methods section). As mentioned, the inclusion of message-level data in future studies is another strategy to further validate the issue tags labeled by the crisis counselors. Lastly, individuals who use the hotline are a self-selecting population who are seeking help. The findings do not speak to psychosocial issues that non-help seeking suicidal individuals endure.

Typically, hotline studies are naturalistic studies and do not include a control sample, as callers are impacted by various life circumstances and may engage in various help-seeking activities (38). While a comparison sample was not available to the authors, future studies may include a sample of non-suicidal texters to evaluate differences and similarities in presenting psychosocial issues of texters.

Conclusion

Text-message hotlines are one strategy to reach diverse groups of suicidal people nationwide. Yet, there is a disparity in peer-reviewed research that explores the meaningful subgroups of suicidal texters. Findings suggest that most suicidal texters struggle with psychological and relational issues. However, there are distinct subgroups of texters that are facing a unique constellation of issues. Crisis counselors may benefit from additional training on emotion regulation and interpersonal problem solving, and from understanding which issues tend to co-occur. This will allow crisis counselors to inquire about additional but unexpressed- issues. Findings also have implications for how the hotline may supplement collection of texter information through user identification of psychosocial issues and message-level data. This information may inform how the severity and types of issues differ among subgroups of suicidal texters and inform future implementation of hotline services.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

This is one of few studies to explore distinct classes of suicidal hotline users based on their presenting psychosocial issues across frequency of hotline use and conversation number

Conversations from Crisis Text Line provide an opportunity to examine how suicidal users’ psychosocial issues may vary by frequency of hotline usage and by users’ first and last conversations.

Latent class analysis identified three user classes: Lower Distress, Anxious Distress, and Relational Distress.

Across frequency of hotline usage and conversation subsamples, most suicidal texters are endorsing similar issues, yet there appears to be distinct subgroups of texters based on presenting psychosocial issues.

Acknowledgements:

Research is reflective of the first and third authors’ ongoing collaboration with Crisis Text Line.

Funding: The University of Texas at Austin Health Communications Scholars Program (HCSP) supported the early phase of the study.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32MH019960 (regarding the first and second authors). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: Authors have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]: Vital signs: Suicide rising across the U.S [Internet], 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/index.html

- 2.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans WP, Davidson L, Sicafuse L: Someone to Listen: Increasing Youth Help-Seeking Behavior Through a Text-Based Crisis Line for Youth. Journal of Community Psychology 41: 471–487, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Litman RE, Farberow NL, Shneidman ES, et al. : Suicide-Prevention Telephone Service. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 192: 107–111, 1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dew MA, Bromet EJ, Brent D: A Quantitative Literature Review of the Effectiveness of Suicide Prevention Centers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55: 239–244, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer-Thomas S, Jahn DR: Tracking a Movement: U.S. Milestones in Suicide Prevention: Suicide Prevention Movement. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 42: 78–85, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PBS News: As calls to the Suicide Prevention Lifeline surge, under-resourced centers struggle to keep up [Internet]. PBS NewsHour, 2018. Available from: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/suicide-prevention-lifeline-centers-calls [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crosby Budinger M, Cwik MF, Riddle MA: Awareness, attitudes, and use of crisis hotlines among youth at-risk for suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 45: 192–198, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramchand R, Jaycox L, Ebener P, et al. : Characteristics and Proximal Outcomes of Calls Made to Suicide Crisis Hotlines in California: Variability Across Centers. Crisis 38: 26–35, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Center for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]: National Violent Death Reporting System, data from 27 states participating in 2015 [Internet], 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/suicide/infographic.html#graphic3

- 11.Middleton A, Pirkis J, Chondros P, et al. : The Health Service Use of Frequent Users of Telephone Helplines in a Cohort of General Practice Attendees with Depressive Symptoms. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 43: 663–674, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirkis J, Middleton A, Bassilios B, et al. : Frequent callers to telephone helplines: new evidence and a new service model. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10: 43, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Middleton A, Woodward A, Gunn J, et al. : How do frequent users of crisis helplines differ from other users regarding their reasons for calling? Results from a survey with callers to Lifeline, Australia’s national crisis helpline service. Health & Social Care in the Community 25: 1041–1049, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gould MS, Lake AM, Galfalvy H, et al. : Follow-up with Callers to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: Evaluation of Callers’ Perceptions of Care. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 48: 75–86, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Predmore Z, Ramchand R, Ayer L, et al. : Expanding Suicide Crisis Services to Text and Chat. Crisis 38: 255–260, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crisis Textline: Crisis Trends [Internet]. Crisis Trends. 2018. Available from: https://crisistrends.org/#faq

- 17.Draper J, McCleery G, Schaedle R: Mental health services support in response to September 11: the central role of the Mental Health Association of New York City; in 9/11: Mental Health in the Wake of Terrorist Attacks. Edited by Neria Y, Gross R, Marshall RD, et al. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halpern P: An American Indian/Alaska Native Suicide Prevention Hotline: Literature Review and Discussion with Experts. 2009

- 19.Gupta A: Detecting Crisis: An AI Solution [Internet]. Crisis Text Line; 2018. Available from: https://www.crisistextline.org/blog/ava2 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berrouiguet S, Baca-García E, Brandt S, et al. : Fundamentals for Future Mobile-Health (mHealth): A Systematic Review of Mobile Phone and Web-Based Text Messaging in Mental Health. Journal of Medical Internet Research 18: e135, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Althoff T, Clark K, Leskovec J: Large-scale Analysis of Counseling Conversations: An Application of Natural Language Processing to Mental Health. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 4: 463–476, 2016. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sindahl TN, Côte L- P, Dargis L, et al. : Texting for Help: Processes and Impact of Text Counseling with Children and Youth with Suicide Ideation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dinakar K, Chen J, Lieberman H, et al. : Mixed-Initiative Real-Time Topic Modeling & Visualization for Crisis Counseling; in Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces Atlanta, Georgia, ACM Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grigorash A, O’Neill S, Bond R, et al. : Predicting Caller Type from a Mental Health and Well-Being Helpline: Analysis of Call Log Data. JMIR Mental Health 5: e47, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohtaki Y, Oi Y, Doki S, et al. : Characteristics of Telephone Crisis Hotline Callers with Suicidal Ideation in Japan. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 47: 54–66, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pisani AR, Kanuri N, Filbin B, et al. : Protecting User Privacy and Rights in Academic Data-Sharing Partnerships: Principles from a Pilot Program at Crisis Text Line. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21: e11507, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mokkenstorm JK, Eikelenboom M, Huisman A, et al. : Evaluation of the 113Online Suicide Prevention Crisis Chat Service: Outcomes, Helper Behaviors and Comparison to Telephone Hotlines. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 47: 282–296, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gould MS, Greenberg T, Munfakh JLH, et al. : Teenagers’ Attitudes about Seeking Help from Telephone Crisis Services (Hotlines). Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 36: 601–613, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman LA: Exploratory Latent Structure Analysis Using Both Identifiable and Unidentifiable Models. Biometrika 61: 215–231, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazarsfeld PF, Henry NW: Latent structure analysis. New York, Houghton, Mifflin, 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masyn KE: Latent Class Analysis and Finite Mixture Modeling; in The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods in Psychology: Vol. 2. New York, Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO: Deciding on the Number of Classes in Latent Class Analysis and Growth Mixture Modeling: A Monte Carlo Simulation Study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 14: 535–569, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB: Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika 88: 767–778, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Celeux G, Soromenho G: An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification 13: 195–212, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Asparouhov T, Muthen B: Variable-Specific Entropy Contribution. Los Angeles, Muthén & Muthén, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthén LK, Muthén BO: Mplus User’s Guide, Eighth Los Angeles, CA, Muthén & Muthén, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gould MS, Kalafat J, Harrismunfakh JL, et al. : An evaluation of crisis hotline outcomes. Part 2: Suicidal callers. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 37: 338–352, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mishara BL, Chagnon F, Daigle M, et al. : Which Helper Behaviors and Intervention Styles are Related to Better Short-Term Outcomes in Telephone Crisis Intervention? Results from a Silent Monitoring Study of Calls to the U.S. 1–800-SUICIDE Network. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 37: 308–321, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.