Dear Editor,

Currently there are few evidence based treatments for Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD), and those that are available have limited efficacy [1]. Cannabis craving is a commonly described behavioral construct in CUD [2], and may have clinical relevance. An expanding evidence base suggests that repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) applied to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) decreases craving across a variety of different substance use disorders and may have treatment efficacy [3]. We recently reported that it was both safe and feasible to deliver a single session of rTMS to non-treatment seeking participants with CUD [4]; however, to date, no trial has attempted to apply a multi-session course of rTMS to individuals with CUD interested in reducing use. We sought to determine the feasibility of delivering such a course in this population and to determine a preliminary effect size to inform future research. We did so by performing an open-label pilot safety and tolerability trial, applying 20-sessions of rTMS over two weeks to participants with CUD who were interested in reducing use. Participants were then followed for four-weeks to determine if there was a potential treatment effect. The protocol was approved by the Medical University of South Carolina’s institutional review board, and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03538288).

Participants were recruited from the community, and underwent a standardized evaluation [5–8]. Participants were included if they heavily used cannabis (>20 days/month), met DSM-5 criteria for ≥moderate CUD, had a desire to reduce use, and were aged 18−60. Participants were excluded if they were pregnant/breast-feeding; met ≥moderate use disorder of any other substance besides tobacco; required treatment for another psychiatric condition; were taking central nervous system active medications; or had any contraindications to receiving rTMS.

Enrolling participants who met inclusion/exclusion criteria were scheduled to have 10 treatment visits (each consecutive weekday for two weeks), where twenty sessions of rTMS were delivered. Stimulation was delivered at the EEG coordinate for F3 (closely approximating the Left DLPFC), using a Magventure Mag-pro x100 with a Cool-B65-coil. Each rTMS session consisted of 4000 pulses of 10Hz stimulation (5s-on,10s-off,120% of resting motor threshold). Physical and olfactory cannabis cues similar to Ref. [9] were presented throughout rTMS. Two rTMS sessions were delivered at each visit with a 30-min break between sessions. Participants also received two sessions of weekly motivational enhancement therapy. Following the ten-treatment visits, participants attended follow-up visits (two and four weeks) and were provided CUD referral information.

Of nine enrolled participants, two were lost to follow-up before attending any treatment visits, one dropped after their 3rd treatment visit due to headaches following treatments, and three dropped prior to the 1st, 3rd, and 6th treatment visits respectively due to conflicts with their work schedule. Three participants completed the protocol. Beyond the participant that described headaches and dropped out, no other adverse events were reported. The three completing participants included a 48yo Caucasian woman, a 26yo Native American man, and a 41yo Caucasian man.

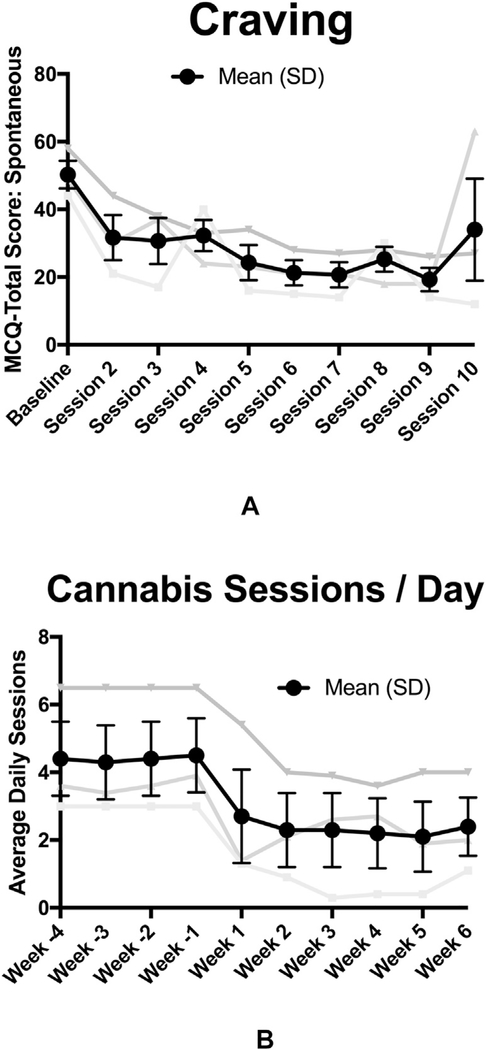

Spontaneous craving was measured at the beginning of each visit using the Marijuana Craving Questionnaire short form (MCQ-SF) [7]. Mean MCQ-SF scores dropped from 50.3 ± 7.1 prior to visit one to 34.0 ± 26.2 prior to the final visit (Fig. 1a; Cohen’s d = 1.3). The 48yo woman reported decreased craving up until the final visit when she had a severe social stressor that she reported increased her craving (MCQ: visit-1 =49, visit-9 = 18, and visit-10 = 63). Cannabis use was measured using the Time Line Follow-Back(8), with a primary outcome of average weekly usesessions. Cannabis use decreased from 31.7 ± 15.1 use-sessions per week at baseline, to 17.0 ± 13.5SD, 17.7 ± 12.3SD, 15.3 ± 12.1SD, and 15.3 ± 12.1SD use-sessions per week respectively in the four weeks following treatment (Fig. 1b; Cohen’s d = 1.2).

Fig. 1.

a) Marijuana Craving Questionnaire Short Form (MCQ-SF) Total Score, recorded prior to each of the denoted treatment visits; and 1b) Average number of cannabis use sessions per day as measured by the Time Line Follow-back (TLFB).

To our knowledge, this is the first report that demonstrates that a multi-session course of rTMS can feasibly be applied to CUD individuals who are attempting to reduce use. Given the small sample size, no conclusions can be made regarding craving or use. It is, however, noteworthy that all three completing participants reported less frequent cannabis use following treatment, and two of three participants reported stably lower spontaneous cannabis craving.

The other main finding of this case-series was that the retention rate was low. The low retention rate (33% of enrolled participants, 50% of participants receiving at least one session) compared poorly to trials applying multi-session courses of rTMS to other substance use disordered populations [3] (ranging from 56 to 100%), as well as other treatment trials in CUD [1] (ranging from 36 to 71%). To our knowledge there are no other treatment trials in CUD requiring daily visits for two consecutive weeks, so it is unclear if the low retention rate was related to the clinical population, rTMS itself, or the high level of time intensity. Two pieces of information support the notion that the low retention rate was the result of the time intensity of the protocol, rather than intolerance of rTMS. First, three out of four non-completers who were not lost to follow-up reported scheduling as the main barrier to trial completion. Second, based on the findings of this trial, we have begun a trial of rTMS in a nearly identical study population, however shifted to two treatment visits/week (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03144232), and have thus far had a higher retention rate (63%). The idea that individuals with CUD may have difficulty completing a time intensive intervention is also supported by data suggesting that those with CUD are more likely to be employed, and tend to be more ambivalent towards treatment than those with other substance use disorders [10].

There are several limitations of this study including a low retention rate, a small sample size, and an open label design. Strengths include rigorous screening, the delivery of twenty sessions of rTMS using standardized methods, and the use of validated outcome measures. The described weaknesses limit the ability to draw strong inferences and subsequently no statistics were run. This trial does however provide further support to the notion that rTMS can be used in CUD participants, and that rTMS may ultimately develop into a promising treatment strategy to investigate in this population, especially if participant retention is improved.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant numbers: K23DA043628 (PI: Sahlem, NIH/NIDA), K12DA031794-04 (Co-PI’s McRae-Clark and Gray, NIH/NIDA), K24DA038240-01 (PI: McRae-Clark, NIH/NIDA). We would like to thank all of the many contributors to this work including Dr. Lindsay Squeglia, Phillip Summers, Amanda Wagner, and Dr. Therese Killeen.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

Clinicaltrials.gov identifier

Contributor Information

Gregory L. Sahlem, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

Margaret A. Caruso, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

E. Baron Short, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA.

James B. Fox, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Brian J. Sherman, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Andrew J. Manett, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Robert J. Malcolm, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA

Mark S. George, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration Medical Center, Charleston, SC, USA.

Aimee L. McRae-Clark, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration Medical Center, Charleston, SC, USA.

References

- [1].Sherman BJ, McRae-Clark AL. Treatment of cannabis use disorder: current science and future outlook. Pharmacotherapy 2016;36(5):511e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Norberg MM, Kavanagh DJ, Olivier J, Lyras S. Craving cannabis: a meta-analysis of self-report and psychophysiological cue-reactivity studies. Addiction 2016;111(11):1923e34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Coles AS, Kozak K, George TP. A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. Am J Addict 2018;27(2):71e91 American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Sahlem GL, Baker NL, George MS, Malcolm RJ, McRae-Clark AL. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) administration to heavy cannabis users. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2018;44(1):47e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hamilton M A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960;23:56e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Heishman SJ, Evans RJ, Singleton EG, Levin KH, Copersino ML, Gorelick DA. Reliability and validity of a short form of the marijuana craving Questionnaire. Drug Alcohol Depend 2009;102(1e3):35e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sobell LC aSM. Timeline follow-back. Measuring alcohol consumption. 1992. p. 41e72.

- [9].McRae-Clark AL, Carter RE, Price KL, Baker NL, Thomas S, Saladin ME, et al. Stress- and cue-elicited craving and reactivity in marijuana-dependent individuals. Psychopharmacology 2011;218(1):49e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Budney AJ, Radonovich KJ, Higgins ST, Wong CJ. Adults seeking treatment for marijuana dependence: a comparison with cocaine-dependent treatment seekers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;6(4):419e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]