Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has created uncertainty in the management of patients with severe aortic stenosis. This population experiences high mortality from delays in treatment of valve disease but is largely overlapping with the population of highest mortality from COVID-19. The authors present strategies for managing patients with severe aortic stenosis in the COVID-19 era. The authors suggest transitions to virtual assessments and consultation, careful pruning and planning of necessary testing, and fewer and shorter hospital admissions. These strategies center on minimizing patient exposure to COVID-19 and expenditure of human and health care resources without significant sacrifice to patient outcomes during this public health emergency. Areas of innovation to improve care during this time include increased use of wearable and remote devices to assess patient performance and vital signs, devices for facile cardiac assessment, and widespread use of clinical protocols for expedient discharge with virtual physical therapy and cardiac rehabilitation options.

Key Words: aortic stenosis, COVID-19, SAVR, TAVR

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AS, aortic stenosis; AVR, aortic valve replacement; COVID-19, coronavirus disease-2019; CTA, computed tomographic angiography; PFT, pulmonary function test; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TTE, transthoracic echocardiographic

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) has altered the clinical landscape because of its infectivity rate and the severity of respiratory and hemodynamic distress caused by infection (1). Strategies to mitigate COVID-19 spread involve decreased interpersonal interaction, a significant disruption to our typical evaluation and management of patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS). Severe, symptomatic AS conveys high morbidity and mortality when left untreated (2). However, severe AS most commonly affects elderly patients and is frequently accompanied by comorbidities of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and type 2 diabetes, the same conditions that pose the greatest risk for poor outcomes from COVID-19 (3).

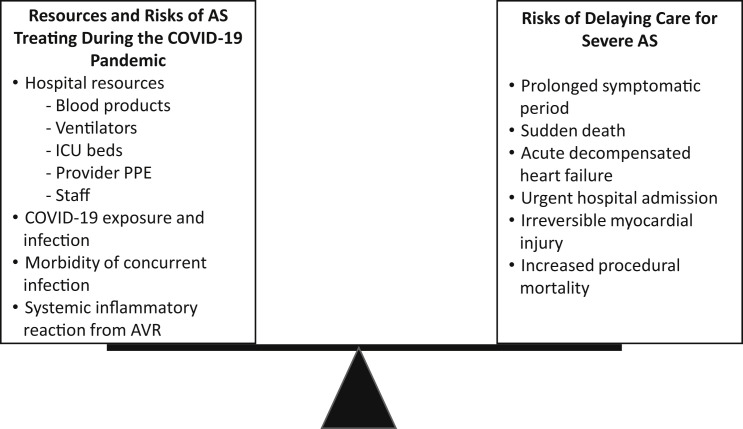

COVID-19 risk mitigation strategies focus on reduction of face-to-face clinical visits and unnecessary interventions that consume personal protective equipment and health care resources while exposing patients to risk for infection (4, 5, 6). The Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services suggested postponing elective procedures and limiting cardiac surgical procedures to only high-acuity and “highly symptomatic” patients (7). Thus, providers face the complex task of balancing the risks of delayed aortic valve replacement (AVR) in patients with severe symptomatic AS versus those of COVID-19 exposure and infection in an at-risk population (Figure 1 ). Here, we present clinical strategies for the management of patients with severe AS in the COVID-19 era. In this unprecedented time, a robust evidence base to inform best clinical practice does not exist. Therefore, the recommendations presented are based on our opinions and experience, in an attempt to best manage patients with AS in a resource-constrained health care system.

Figure 1.

Risks of Treating Severe AS Balanced With Risks of Delayed Treatment

AS = aortic stenosis; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019; ICU = intensive care unit; PPE = personal protective equipment.

Outpatient Surveillance and Risk Stratification

Prompt referral and evaluation for AVR is normally paramount for patients with symptomatic severe AS, leading to the adoption of “wait time” as a quality metric in the management of patients with AS (8) (Table 1 ). Even small delays in AVR are associated with increased morbidity and mortality, with the highest risk patients having up to 20% mortality at 3 months (2,9,10). In the COVID-19 era, however, risks of delayed AVR need to be balanced against resource constraints and risks of patient exposure to infection, which carries a 10% to 20% mortality rate in elderly patients (3) (Figure 1). Despite the urgency normally assigned to any form of symptomatic severe AS, we and others recommend stratifying patients on the basis of symptom severity as follows (11,12) (Table 2 ):

-

•

Mild, stable symptoms include generalized fatigue, stable exertional dyspnea (allowing for ≥1 flight of stairs), and New York Heart Association functional class II congestive heart failure symptoms. Virtual or telephone assessments every 1 to 3 months are prudent to screen for evidence of disease progression. Deferral of AVR referral until the COVID-19 pandemic abates is warranted if symptoms remain stable.

-

•

Moderate, stable symptoms include mild, stable angina, stable New York Heart Association functional class II or III congestive heart failure symptoms, reduced exertional capacity, exertional dyspnea permitting activities of daily living, and symptoms with chronic, stable left ventricular systolic dysfunction. These patients may be monitored virtually every 1 to 2 weeks or treated urgently on the basis of local resource availability during the COVID-19 pandemic (13).

-

•

Severe or unstable symptoms apply to patients with New York Heart Association functional class III or IV CHF symptoms, progressive weight gain, rapidly decreasing exertional capacity or with minimal exertion, progressive or severe angina, syncope, and new onset pre-syncope. In-person assessments and repeat transthoracic echocardiographic (TTE) imaging may be required to assess for new left ventricular dysfunction. Urgent AVR is prudent despite COVID-19-related risks.

Table 1.

Typical Versus COVID-19-Era Care of a Patient With Symptomatic Severe AS

| Typical Care | COVID-19-Era Care |

|---|---|

| Patient assessment by primary cardiologist | |

|

|

| Patient assessment by consulting providers | |

|

|

| Testing | |

|

|

| Post-procedurally | |

|

|

AS = aortic stenosis; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease-2019; CTA = computed tomographic angiography; PT = physical therapy; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TTE = transthoracic echocardiography.

Table 2.

Severe Aortic Stenosis Treatment Priorities During the COVID-19 Era

| Urgent AVR |

|

| Consider AVR on the basis of local resources |

|

| Defer AVR during COVID-19 pandemic |

|

AVR = aortic valve replacement; COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

Those with asymptomatic severe AS should be monitored every 6 months by virtual visit, with TTE examinations performed only in response to new-onset symptoms or other changes in clinical status (14). All patients should be counseled to maintain a consistent activity level and to promptly communicate changes in their functional capacity or new-onset symptoms, including dyspnea, decreased exertional capacity, lower extremity or abdominal edema, orthopnea, angina, progressive fatigue, and pre-syncope. Caregiver and family member involvement in virtual visits can facilitate home monitoring of potential symptoms and improved understanding of clinicians’ decision making during this unusual time.

Guidance: Risk stratification for patients with symptomatic severe AS during the COVID-19 pandemic should:

-

•

use virtual visits to remotely assess patient symptoms and progression;

-

•

classify symptom status as mild, moderate, or severe/unstable, as outlined in Table 2;

-

•

trigger prompt AVR evaluation for patients with severe or unstable symptoms; and

-

•

remotely surveil patients with mild, stable symptoms every 1 to 3 months.

Evaluation for AVR

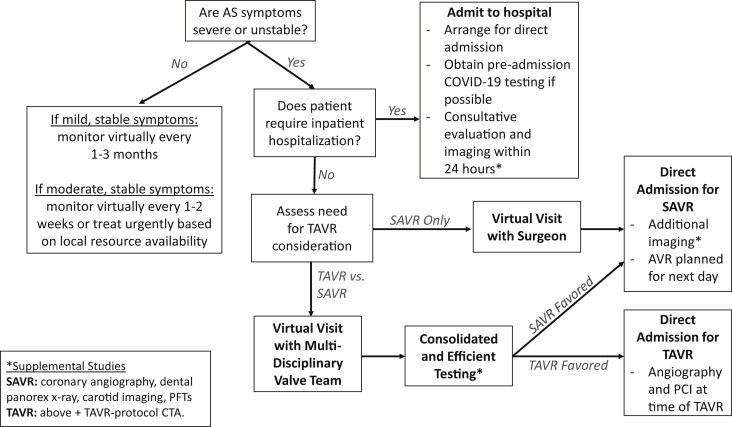

When symptom severity or progression mandates prompt AVR evaluation (Figure 2 ), medical urgency and institutional resources should guide whether an inpatient or outpatient evaluation strategy should be used.

Figure 2.

Suggested Treatment Strategies for Patients With Severe Symptomatic AS

CTA = computed tomographic angiography; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PFT = pulmonary function test; SAVR = surgical aortic valve replacement; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; other abbreviations as in Figure 1.

Echocardiographic evaluation

New or progressive heart failure symptoms may necessitate urgent TTE imaging with the appropriate precautions to minimize contamination of staff members, patients, and equipment (15). There is concern for prolonged coronavirus viability on plastics, making TTE equipment highly susceptible to acting as a fomite without thorough cleaning techniques (16). Sonographers may typically spend up to 1 h in close proximity to patients for full TTE studies, placing them at high risk for coronavirus exposure (15). Strategies to prevent equipment contamination and minimize exposure risk for patients and sonographers include deferring unnecessary tests; shortening studies to focus on AS severity, left ventricular systolic function, and exclusion of other severe valve lesions; using smaller machines (i.e., point-of-care ultrasound) that are easier to clean; and using disposable plastic covers for machines and probes (15). Transesophageal echocardiography, which can aerosolize viral particles, should be avoided.

Inpatient assessment strategy

Direct admission to a cardiac or telemetry inpatient bed should be favored over referral to the emergency department to minimize interaction with other patients and to reduce the burden on frontline providers and emergency department resources. Pre-admission COVID-19 testing should be obtained if possible. Inpatient services should be carefully orchestrated to facilitate consultative evaluation and necessary testing, imaging, and procedures expeditiously.

Outpatient AVR assessment strategy

Multidisciplinary visits with valve team members and the treatment coordinator can be performed virtually and should focus on the stratification of cardiac symptoms, risk assessment, counseling regarding the natural history of AS, and the comparative risks and benefits of available treatment strategies. A shared decision-making approach should be used to determine the selection of transcatheter AVR (TAVR) and surgical AVR (SAVR). Activities of daily living should be assessed, and if possible, a virtual frailty walk test (i.e., visualize the patient standing from a chair and timed while walking 15 feet) (17).

Guidance: AVR evaluation for patients with symptomatic severe AS during the COVID-19 pandemic should:

-

•

minimize interpersonal contacts and COVID-19 exposure risk;

-

•

invoke direct hospital admission and facilitated assessment for acute illness;

-

•

use virtual health platforms to predict operative risk, assess frailty, and counsel patients regarding AS and treatment options; and

-

•

incorporate focused TTE imaging for new or progressive heart failure symptoms at facilities using COVID-19 exposure risk mitigation.

Treatment Strategies (TAVR vs. SAVR)

The choice of TAVR versus SAVR should continue to be made by a heart team using evidence-based and individualized patient criteria in the COVID-19 era. SAVR should remain the favored approach in younger low-risk patients, especially those in whom mechanical AVR is being considered or with aortic dilatation, complex root anatomy, or additional indications for cardiac surgery. Because TAVR usually requires a shorter length of hospital stay and less resource utilization compared with SAVR, it should be preferred for patients who would receive bioprosthetic valves (18, 19, 20). TAVR may be performed in the cardiac catheterization laboratory with fewer staff members using monitored anesthesia or conscious sedation, eliminating the need for operating room resources (21). Furthermore, procedural recovery after TAVR often occurs in a standard telemetry bed, as opposed to an intensive care unit bed after SAVR. To the extent possible, patient and provider preference for TAVR or SAVR should be determined at the time of the virtual visit to inform further customization of subsequent testing.

Guidance: In considering SAVR versus TAVR for patients with symptomatic severe AS during the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

•

SAVR should remain the favored approach in younger patients in whom mechanical AVR is being considered, who have unfavorable anatomy for TAVR, or with additional indication for cardiac surgery;

-

•

TAVR should be preferred in elderly patients and those being considered for bioprosthetic valves;

-

•

patient and provider preference for TAVR or SAVR should be determined early in the evaluation to inform customization of subsequent testing; and

-

•

the Society for Thoracic Surgeons Resource Utilization Tool can be used to inform heart team decisions in locales where COVID-19 is limiting resource availability (22).

When SAVR is the preferred strategy, the initial surgical visit should be completed virtually. Cardiac catheterization should be performed either on an outpatient basis or via direct admission, with plans for SAVR on the following day. Prolonged inpatient wait times prior to SAVR should be avoided. Dental panorex radiography, carotid imaging, and pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are commonly performed prior to SAVR, but in the COVID-19 era, diagnostic testing should be minimized or eliminated. PFTs should be deferred in patients without smoking histories and performed only if severe pulmonary disease is suspected. Dental evaluation should similarly be triaged on the basis of the presence of gross dental symptoms or pathology. Rapid testing for COVID-19 prior to admission should be considered when available. If concomitant coronary revascularization is being considered, venous mapping should be obtained in the inpatient setting immediately prior to SAVR or forgone.

Guidance: In evaluation for SAVR for patients with symptomatic severe AS during the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

•

perform dental panorex radiography, carotid imaging, vein mapping, and PFTs only when results will change critical management decisions; and

-

•

cardiac catheterization should be obtained either on an outpatient basis or via direct admission with plans for SAVR on the following day.

A consolidated and prioritized diagnostic testing approach similar to that in the SAVR strategy may be adopted for TAVR. TAVR-protocol computed tomographic angiography (CTA) is a crucial component of determining TAVR eligibility and should be performed early in the AVR evaluation to inform management. TAVR protocols for CTA can be adapted to exclude assessment for proximal coronary artery disease and severe carotid artery disease in order to maximize the information obtained and reduce the need for additional testing. Hallmark features of COVID-19 infection on chest CTA should also be used to supplement COVID-19 testing given its variable sensitivity (23). PFTs can be deferred unless anticipated to change management. In a patient at high risk for heart block, a virtual visit with an electrophysiologist can be considered prior to the procedural admission for discussion of pacemaker placement. Following the TAVR evaluation, a virtual multidisciplinary heart team meeting should be convened, with review of the pertinent data to finalize the appropriate treatment strategy.

If a patient is accepted for TAVR, coronary angiography with percutaneous coronary intervention as needed may be performed at the time of TAVR. Using moderate sedation and TTE guidance rather than general anesthesia and transesophageal echocardiography avoids particle aerosolization with esophageal and tracheal intubation and should be the favored approach when appropriate. The adoption of monitored anesthesia and the “minimalist TAVR approach” may also contribute to reduced length of stay, decreased mortality, and more frequent discharge home compared with general anesthesia (21).

Guidance: In evaluation for TAVR in patients with symptomatic severe AS during the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

•

TAVR-protocol CTA should include coronary and carotid artery assessment;

-

•

TAVR-protocol CTA should be completed early in the evaluation process given its critical role in determining anatomic TAVR candidacy;

-

•

virtual heart team meetings should be conducted after completion of assessment to weigh treatment strategies;

-

•

in patients with suspected proximal obstructive coronary artery disease, invasive coronary angiography and revascularization may be performed at the time of TAVR; and

-

•

TAVR should be performed under monitored anesthesia care and TTE guidance when possible to avoid aerosol generation.

Post-procedural care

After SAVR, early extubation and mobilization can facilitate a shorter length of stay (24). Transfer out of the intensive care unit within 24 h should be routinely accomplished barring medical complexity or instability (18,25).

Hospital discharge within 24 to 48 h after TAVR is feasible without significant increases in mortality, poor outcomes, or readmission rates (25). Teams should strive to remove femoral and upper extremity lines at the completion of the case (25). In addition, assessments for pacemaker need should be expedited. Consideration should be given to immediate implantation of permanent pacemakers at the time of TAVR for patients with atrioventricular block and high-risk features such as slow or absent escape rhythms or hemodynamic instability (25). Mobile cardiac telemetry monitoring should be used for continued outpatient monitoring beyond 24 to 48 h for patients with new or increased bundle branch block or atrioventricular block (25,26).

For both TAVR and SAVR, expedited attention from services including physical, occupational, and speech-language therapy is critical in the COVID-19 era. Nursing and care coordinators can assist with rapid discharge planning prioritizing discharges to patients’ homes rather than to rehabilitation facilities where infection risk may be higher. Rapid COVID-19 screening for visitors may allow greater presence of family members at the bedside, which may in turn improve safety upon discharge.

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology TVT (Transcatheter Valve Therapy) Registry typically mandates 30-day clinical follow-up, including post-TAVR TTE imaging, but has recommended deferral of TTE imaging in the absence of clinical concerns (27). Virtual clinical assessment should be performed, and quality-of-life questionnaires and additional data requested by the TVT Registry should be collected.

Guidance: Post-procedural care after AVR during the COVID-19 pandemic should:

-

•

accelerate extubation and transfer out of the intensive care unit after SAVR;

-

•

focus attention on accelerated physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech-language therapy to support rapid mobilization and diet advancement;

-

•

target hospital discharge within 24 h after TAVR;

-

•

use mobile cardiac telemetry monitors over prolonged hospitalization for patients with conduction disturbances not meeting indications for permanent pacemaker implantation; and

-

•

defer routine follow-up echocardiographic assessment in the absence of clinical concerns.

Patients With Severe AS Who Contract COVID-19

We are likely to care for patients who have severe AS with concurrent COVID-19. In a critically ill patient, the immediate focus should be on the management of COVID-19 illness. However, the robust inflammatory response caused by COVID-19 may result in complicated hemodynamics for those with severe or critical AS. In the setting of severe COVID-19, balloon aortic valvuloplasty or emergent TAVR may be considered if cardiac decompensation hinders clinical recovery (28). SAVR should be undertaken only in extreme cases given the risk for the inflammatory response and pulmonary dysfunction commonly seen after cardiopulmonary bypass. Management and evaluation of severe AS should be deferred in patients with active COVID-19 in the absence of an emergent need for AVR. Similarly, persons under investigation for possible COVID-19 should be managed conservatively until cleared with negative COVID-19 test results, unless there is an emergent need for AVR; however, decisions in such situations must be guided by local infection control policies, personal protective equipment availability, and the population prevalence of COVID-19 and should evolve in conjunction with the state of the pandemic.

Areas for Innovation

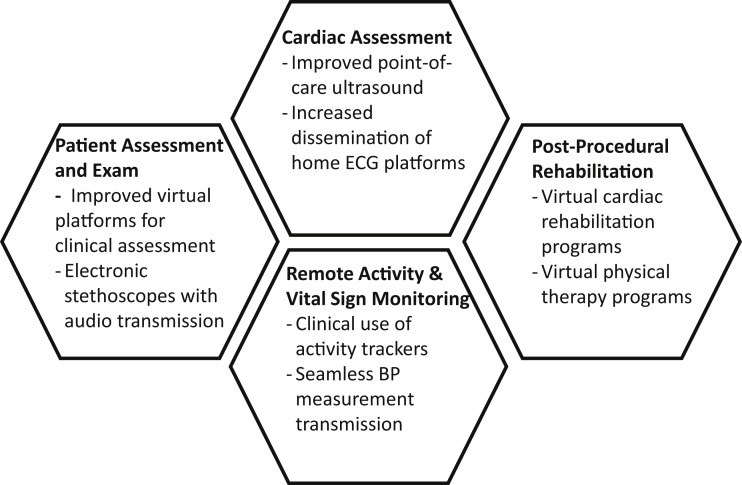

Although many novel technologies to facilitate continued medical care in the COVID-19 era exist, dissemination, operationalization, and incorporation into existing clinical platforms remain barriers. These barriers are not insurmountable for rapid uptake: states expanded telehealth early in the pandemic, which resulted in rapid uptake of telemedicine (29). The duration of this public health emergency remains uncertain, and thus investment in innovative health care technologies is critical. Improved virtual platforms that allow transmission of blood pressure readings, tracking of physical activity, and widespread use of home electrocardiographic platforms or digital stethoscopes with recordable audio would allow a more complete remote clinical assessment (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Areas of Innovation to Facilitate Care of Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis

BP = blood pressure; ECG = electrocardiographic.

Innovative protocols that expedite discharge without significant sacrifices in outcomes or that move virtual recovery services to patients’ homes would also facilitate care in the COVID-19 era. For example, a caregiver may be instructed in physical therapy techniques and engage in virtual physical therapy sessions (30). In addition, cardiac rehabilitation could be made virtual with wearable devices for transmission of hemodynamic parameters, electrocardiographic monitoring during structured exercise, and activity levels (31). Virtual post-operative visits may allow more timely follow-up after discharge, improve medication reconciliation, and ease patient anxiety about appropriate activity and expectations.

Conclusions

Patients with severe AS pose a challenge during the COVID-19 pandemic because of their high resource utilization and increased mortality from delays in care but substantial risk for poor outcomes from COVID-19 (2,4). Our proposed strategies for monitoring and treating patients with severe AS on the basis of current epidemiology and testing patterns strive to minimize the risk for coronavirus exposure and infection while also providing a high level of clinical care to patients with severe AS.

Footnotes

Dr. Passeri has received institutional research support from Edwards Lifesciences; has been a speaker at an educational symposium sponsored by Medtronic; and has received consulting fees from Medtronic. Dr. Mack served as co–primary investigator for the PARTNER trial for Edwards Lifesciences and the COAPT trial for Abbott; and served as study chair for the APOLLO trial for Medtronic. Dr. Inglessis has received institutional research support from Medtronic, St. Jude Medical, and W.L. Gore & Associates; and is a proctor for Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Hung has received support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 HL141917). Dr. Elmariah has received research grants from the American Heart Association (19TPA34910170), the NIH (R01 HL151838), Edwards Lifesciences, Svelte Medical, and Medtronic; and has received consulting fees from AstraZeneca. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Cardiovascular Interventionsauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malaisrie S.C., McDonald E., Kruse J. Mortality while waiting for aortic valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1564–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bialek S., Boundy E., Bowen V. Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emanuel E.J., Persad G., Upshur R. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2049–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb2005114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang D., Xu H., Rebaza A., Sharma L., Dela Cruz C.S. Protecting health-care workers from subclinical coronavirus infection. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e13. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siddiqui S. CMS adult elective surgery and procedures recommendations. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-elective-surgery-recommendations.pdf Available at:

- 8.Asgar A.W., Lauck S., Ko D. Quality of care for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: development of Canadian Cardiovascular Society Quality Indicators. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32 doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.11.008. 1038.e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leon M.B., Smith C.R., Mack M. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597–1607. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbaz-Greener G., Masih S., Fang J. Temporal trends and clinical consequences of wait times for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a population-based study. Circulation. 2018;138:483–493. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah P.B., Welt F.G.P., Mahmud E. Triage considerations for patients referred for structural heart disease intervention during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: an ACC /SCAI consensus statement. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2020;13:1484–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung C.J., Nazif T.M., Wolbinski M. Restructuring of structural heart disease practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2974–2983. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turina J., Hess O., Sepulcri F., Krayenbuehl H.P. Spontaneous course of aortic valve disease. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:471–483. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American College of Cardiology General guidance on deferring non-urgent CV testing and procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2020/03/24/09/42/general-guidance-on-deferring-non-urgent-cv-testing-and-procedures-during-the-covid-19-pandemic?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter_post&utm_campaign=covid-19 Available at:

- 15.Kirkpatrick J.N., Mitchell C., Taub C., Kort S., Hung J., Swaminathan M. ASE statement on protection of patients and echocardiography service providers during the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3078–3084. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Doremalen N., Bushmaker T., Morris D.H. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray L.C., Fatehi F., Martin-Khan M., Peel N.M., Smith A.C. Telemedicine for specialist geriatric care in small rural hospitals: preliminary data. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:1347–1351. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arora S., Strassle P.D., Kolte D. Length of stay and discharge disposition after transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.118.006929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leon M.B., Smith C.R., Mack M.J. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609–1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1514616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kolte D., Vlahakes G.J., Palacios I.F. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1532–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.06.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butala N., Chung M., Secemsky E. Conscious sedation versus general anesthesia for transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results of an instrumental variable analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Society of Thoracic Surgeons Resource Utilization Tool. https://www.sts.org/resources/resource-utilization-tool Available at:

- 23.Kucirka L.M., Lauer S.A., Laeyendecker O., Boon D., Lessler J. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction–based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med. 2020 May 13 doi: 10.7326/M20-1495. [E-pub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engelman D.T., Ben Ali W., Williams J.B. Guidelines for perioperative care in cardiac surgery: enhanced recovery after surgery society recommendations. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:755–766. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood D.A., Lauck S.B., Cairns J.A. The Vancouver 3M (Multidisciplinary, Multimodality, But Minimalist) clinical pathway facilitates safe next-day discharge home at low-, medium-, and high-volume transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement centers: the 3M TAVR study. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2019;12:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodés-Cabau J., Ellenbogen K.A., Krahn A.D. Management of conduction disturbances associated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement: JACC scientific expert panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1086–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carroll J.D., Edwards F.H., Marinac-Dabic D. The STS-ACC Transcatheter Valve Therapy national registry: a new partnership and infrastructure for the introduction and surveillance of medical devices and therapies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1026–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura R.A., Otto C.M., Bonow R.O. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:e521–e643. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baker-Polito administration announces changes to expedite health care licensing, increase support for local boards of health and small businesses. https://www.mass.gov/news/baker-polito-administration-announces-changes-to-expedite-health-care-licensing-increase Available at:

- 30.Prvu Bettger J., Green C.L., Holmes D.J.N. Effects of virtual exercise rehabilitation in-home therapy compared with traditional care after total knee arthroplasty: VERITAS, a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:101–109. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.19.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funahashi T., Borgo L., Joshi N. Saving lives with virtual cardiac rehabilitation. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.19.0624 Available at: