Abstract

Leiomyosarcoma usually arises in the uterus, abdominal and urologic viscera, and walls of large and small blood vessels. However, primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma is extremely rare with only 39 cases previously reported in English-language literature. We report a case of a 29-year-old previously healthy woman with an incidentally found right adrenal-occupying lesion. CT scan revealed a right adrenal mass measuring 3.3×3.4 cm in size. The tumor was successfully removed by laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Postoperative histopathologic examination showed spindle cells arranged in interlacing fascicles with pleomorphism and a high mitotic rate. An immunohistochemical examination showed positive staining for SMA, desmin, vimentin and H-caldesmon, and the diagnosis of a well-differentiated adrenal leiomyosarcoma was established. The patient received no other oncological treatment after surgery and currently has no evidence of residual disease or tumor recurrence according to imaging follow-up.

Keywords: adrenal gland, adrenal gland neoplasms, leiomyosarcoma, adrenalectomy

Introduction

Leiomyosarcoma is a malignant mesenchymal tumor composed of cells showing distinct features of the smooth muscle lineage.1 The most common anatomic sites are the uterus, abdominal and urologic viscera, and walls of large and small blood vessels. Occasionally, these tumors arise in bone, in somatic soft tissues and extremely rarely in the adrenal gland.2,3 In 1981, Choi SH et al reported the first case of primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma (PAL). There are only 39 cases reported in English-language literature so far. Definitive diagnosis of PAL is usually achieved only after pathologic examination of the surgical specimen. Due to the development and wide use of imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) and ultrasonography, unexpected and special incidentaloma lesions can be detected more easily. Herein, we describe a case of a young woman with PAL without any discomfort. In addition, we report on our analysis of pathological features and corresponding data extracted from the 39 reported cases. Our aim is to share our experiences with rare tumors and discuss the epidemiology, anatomical localization, and diagnosis and current treatment strategies.

Case Report

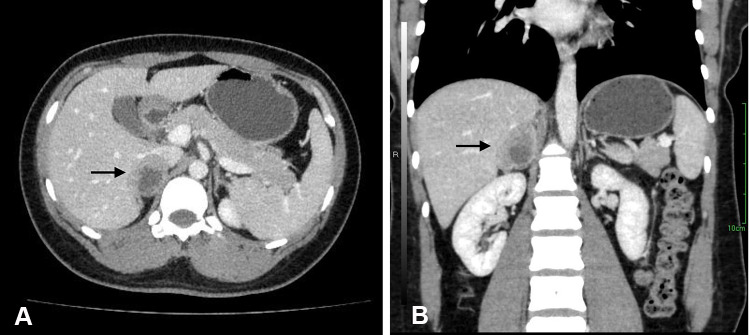

A 29-year-old previously healthy Chinese woman incidentally found a right suprarenal mass by abdominal ultrasound on a preemployment examination. The patient denied systemic symptoms, pain, fever, anorexia, and other notable medical history. Physical examination did not reveal any significant abdominal tenderness, lymphadenopathy or other findings. Routine laboratory examinations were normal, including complete blood count, renal function and electrolyte levels. All the hormonal data showed that 24-h urine cortisol and plasma aldosterone to renin ratio were within normal limits, as were catecholamines and ACTH levels. Cortisol post 1 mg dexamethasone was 0.5 μg/dl (normal < 1.8). HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibody tests were nonreactive. Abdominal ultrasound showed the presence of a diffusely hypoechoic, homogeneous mass in the region of the right suprarenal area measuring 4.2×2.5 cm. We proceeded with computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen, and it revealed a well-defined tumor originating from the right adrenal gland that was 3.3×3.4 cm in size; the tumor, exerted pressure on the hepatic vein without evidence of regional adenopathies or infiltration of surrounding tissues. Contrast-enhanced CT showed moderate enhancement with irregular non-enhanced areas within, suggesting malignancy (Figure 1). A positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan with 18F-FDG was performed, which revealed an exclusive and high uptake in the right adrenal tumor lesion.

Figure 1.

Preoperative abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan showed a well-circumscribed heterogeneously mass in the right suprarenal areal (arrow). (A) Axial sections and (B) coronal sections.

A right adrenalectomy was scheduled and performed uneventfully. Intraoperatively, we found a solid mass that almost completely replaced the right adrenal gland adherent to the posterior wall of the inferior vena cava (IVC). We explored the IVC and adjacent organs, and no tumor invasion was detected. Tissue margins were negative. Postoperatively her vital signs remained stable and as there were no complications. No adjuvant therapy and other medication was given, and the patient was discharged 2 days after surgery. Currently, she is alive and doing well, without evidence of recurrence or distant metastasis at the 12-month follow-up.

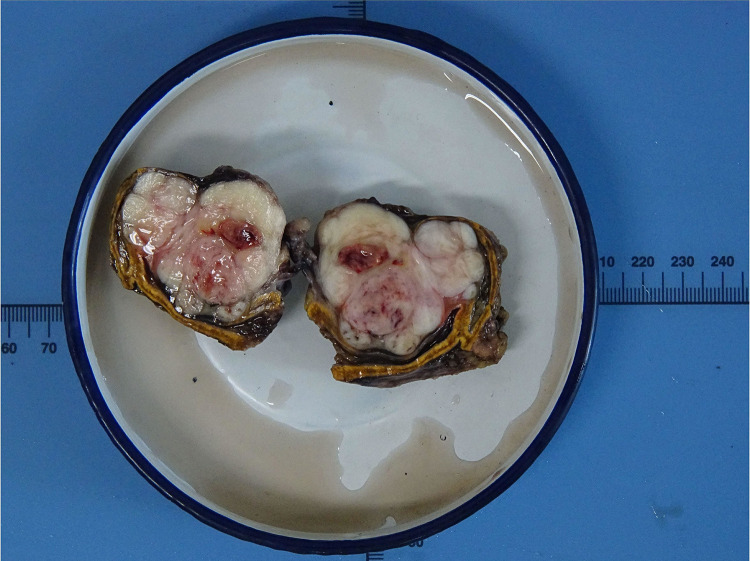

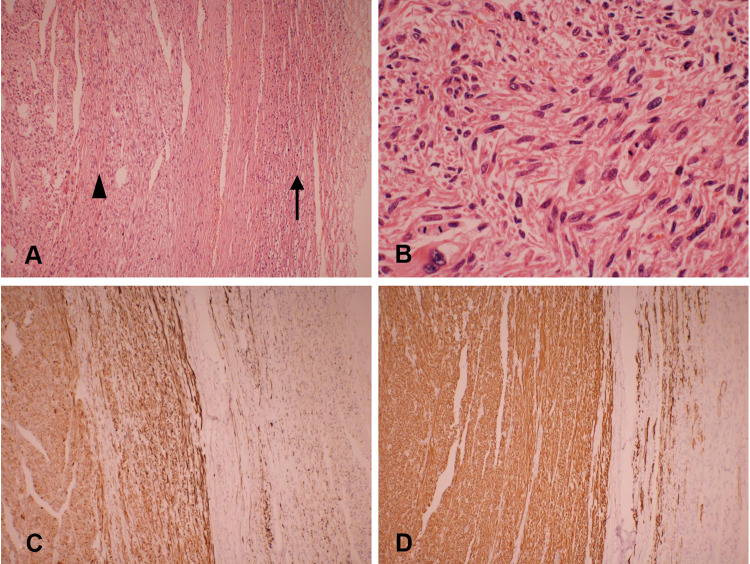

Gross pathological examination showed a well-circumscribed and partially encapsulated solid tumor weighing 37.5 g and measuring 5.5×5×3.2 cm in maximum dimension. The cut surface was nodular and grayish white in color with few mucoidal, hemorrhagic and necrotic areas. The normal adrenal gland was displaced by the tumor and presented at the edge of the tumor (Figure 2). Microscopically, the adrenal gland was compressed, but not invaded by the spindle cell tumor, which was arranged in interlacing fascicles (Figure 3A). Tumor cells were elongated with eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm with marked pleomorphism of the nuclei, with up to 8–10 mitoses/10 high power fields (Figure 3B). No infiltrated lymph nodes were found. An immunohistochemical examination showed positive staining for SMA, desmin (Figure 3C), vimentin, and H-caldesmon (Figure 3D), and negative staining for S-100, CD 117, Dog-1, ER and PR. The Ki-67 proliferation index was approximately 40% in the hot spot. Based on these data, the final diagnosis was confirmed as a primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic features of the tumor showed a well-circumscribed and partially encapsulated solid tumor measuring 5.5×5×3.2 cm in maximum dimension. The normal adrenal gland was displaced by the tumor and presented at the edge of the tumor.

Figure 3.

Microscopic details of the tumor. (A) The interlacing bundle and fascicles of the tumor (arrowhead) and compressed adrenal tissue (arrow). (H&E, × 100). (B) Leiomyosarcoma with nuclear pleomorphism and giant cell formation with mitotic activity in the range of 8–10 mitoses/10 high power fields (H&E, × 400). (C) Immunohistochemical staining for desmin is positive (× 100). (D) Immunohistochemical examinations showed strong immunoreactivity for H-caldesmon (× 100).

Discussion

PAL is an extremely rare nonfunctional mesenchymal tumor, and to the best of our knowledge, there have only been 39 previously published cases of PAL in English-language literature. The clinicopathologic characteristics of these cases are summarized in Table 1. PAL is mostly found in middle-aged adults. The age at first diagnosis ranges from 14 to 79 years, with a mean of 54.2 years. Of these patients, 77.5% have been ≥ 40 years of age. PAL is evenly distributed between the sexes with cases involving 21 women and 19 men. In addition, there does not appear to be any laterality preference, as right-sided and left-sided tumors occur with similar frequency. There have only been two cases of bilateral lesions,4,5 but it is not known whether the bilateral tumors were both primary or if one had metastasized to the other adrenal gland.

Table 1.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Primary Adrenal Leiomyosarcoma

| Author, Year | Age, y/Sex | Presentation | Side | Size (cm) | Treatment | Outcome (months) | Extension | Pathologic Characteristics of Known Cases of PAL in the Literature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our case | 29/F | Incidental finding | R | 5.5 | Adx | 12m AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin/H-caldesmon+ |

| Sakellariou M et al, 202026 | 62/M | Incidental finding | L | 13 | Adx; RT+CT | 31m, alive with bone, lung and liver metastasis | None (preoperative); bone metastasis (postoperative after 3 months) | SMA/desmin+ |

| Nerli RB et al, 201927 | 27/M | Back pain | L | 9 | Adx | N/D | None | Desmin/H-caldesmon+ |

| Doppalapudi SK et al, 20196 | 70/M | Abdominal varices+EBLE | R | 9 | Adx + Nx+ thrombectomy+ cavatomy | 14m, deceased | IVC (preoperative); lung metastasis (postoperative after 12 months) | SMA/desmin/vimentin/H-caldesmon+ |

| Mulani SR et al, 201828 | 50/M | Abdominal pain + weight loss | L | 8.1 | CT+RT | N/D | Liver and lung metastasis | Pleomorphic+ desmin + |

| Onishi T et al, 201629 | 34/M | Flank pain | R | 5.2 | Adx+ Nx+ Ldx+ partial hepatic lobectomy | 10m AWOD | IVC+AO | Pleomorphic+ SMA+ |

| Zhou Y et al, 201524 | 49/F | Abdominal pain+ back pain | L | 8 | Adx | 6m AWOD | None | SMA/desmin/vimentin+ |

| Quildrian S et al, 201530 | 44/F | Abdominal pain | R | 12 | Adx | 36m, AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin/H-caldesmon/HHF+ |

| Nagaraj V et al, 201531 | 61/M | Flank pain | L | 17 | Adx | N/D | None | Pleomorphic+ desmin/vimentin+ |

| Wei J et al, 201432 | 57/F | Incidental finding | L | 8 | Adx; tumor resection+CT | 29m, AWOD | None (preoperative); recurrence (postoperative after 17 months) | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin+ |

| Oztürk H et al, 201433 | 70/F | Flank pain | R | 7.8 | Adx+ cavatomy | 6m, metastasis | IVC | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin + |

| Lee S et al, 201434 | 28/M | Flank pain+weight loss | R | 15 | Adx | 18m, AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin + |

| Gulpinar MT et al, 201435 | 48/M | Frequent urination | R | 11 | Adx | 8m, AWOD | None | SMA/vimentin+ |

| Bhalla A et al, 201436 | 45/M | Back and groin pain+weight loss | R | 11 | CT | 9m, metastasis | Liver metastasis | SMA/desmin+ |

| Alam MM et al, 201437 | 35/F | Flank pain | L | 8.5 | Adx | N/D | None | ND |

| Deshmukh SD et al, 201317 | 60/F | Flank pain | L | 5.2 | Adx | 21m, AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin+ |

| Shao IH et al, 201238 | 66/M | Abdominal fullness + nausea | L | 9.5 | Adx + thrombectomy | 18m, AWOD | Renal vein | SMA/desmin + |

| Karaosmanoglu AD et al, 201039 | 63/M | Abdominal pain+EBLE | R | N/D | CT | 3m, deceased | IVC | Desmin/vimentin/actin+ |

| Kanthan R et al, 201240 | 28/F | Abdominal pain | L | 16.5 | Adx+Nx+partial diaphragmatic resection | N/D | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/vimentin+; desmin- |

| Liu SV et al, 20127 | 79/F | Subcostal pain | L | 6.3 | Adx | 12m, AWOD | N/D | N/D |

| Van Laarhoven HWM et al, 200941 | 78/M | Hemithorax pain | L | N/D | CT+RT | 11days, deceased | Multiple metastases | SMA/vimentin/actin+ |

| Hamada S et al, 20094 | 62/F | Flank pain | B | R(8) L(4) |

Bil Adx+CT+RFA+RT | 16m, deceased | None (preoperative); multiple metastasis (postoperative) | SMA+ |

| Mencoboni et al, 200822 | 75/F | Abdominal pain+ loin pain. | R | 8 | Adx | 12m, AWOD | N/D | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/actin+ |

| Goto J et al, 200820 | 73/F | Flank pain+progressive hypertension | R | 8 | Adx+Nx+cavotomy | 10m, AWOD | AO | SMA/NSE + |

| Wang TS et al, 20078 | 64/F | Non-productive cough+ EBLE | R | 14.2 | Adx+thrombectomy+cavotomy | 10m, AWOD | IVC, right atrium | SMA/desmin+ |

| Mohanty SK et al, 200718 | 47/F | Flank pain | L | 10 | Adx+Nx+RT | 9m, alive with lung and liver metastasis | None (preoperative); lung and liver metastasis (postoperative after 9 months) | Pleomorphic+SMA/desmin/H-calponin/actin+ |

| Lee CW et al, 200642 | 49/M | Flank pain | L | 3 | Adx | 10m, AWOD | None | Desmin+ |

| Wong C et al, 20059 | 57/M | Groin pain +cold feet | L | N/D | Adx+particial Nx+ thrombectomy | 6m, recurrence, deceased | IVC, iliac veins and right atrium | N/D |

| Candanedo-González FA, 200543 | 59/F | Flank pain+weight loss | L | 16 | Adx | 24m, AWOD | None (preoperative); recurrence and liver metastasis (postoperative after 12 months) | Pleomorphic+desmin/vimentin/actin+ |

| Linos D et al, 20045 | 14/F | Incidental finding | B | R(3.5) L(4) |

Bilateral Adx | 14m, AWOD | None | SMA/vimentin/actin/HHF35+ |

| Kato T et al, 200444 | 59/M | Flank pain+back pain. | L | 10 | Adx+Nx+thrombectomy+RT | 6m, deceased | IVC+renal vein (preoperative); bone and liver (postoperative after 1 month) | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin+ |

| Thamboo TP et al, 200321 | 68/F | Loin pain+fever | R | 12.5 | Adx+Nx | 12m, AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/desmin/vimentin/actin+ |

| Lujan MG et al, 200323 | 63/M | Enlarging RUQ mass | R | 25 | Preoperative CT+Adx+Nx+partial hepatic lobectomy+ cholecystectomy | Deceased shortly after surgery |

Invaded AO+lung metastasis | Pleomorphic+ desmin/vimentin/H-calponin +; SMA/actin - |

| Matsui Y et al, 200211 | 61/F | Flank pain+fever | R | N/D | Adx+Nx+thrombectomy | 1m, deceased | AO+IVC+right atrium | SMA+ |

| Etten B et al 200110 | 73/F | EBLE+abdominal pain | R | 27 | Palliative + supportive care | 3 weeks, deceased | IVC+AO | SMA+ |

| Boman F et al, 199745 | 29/M | Autopsy | L | 0.8 | None | N/D | None | SMA/HHF35+ |

| Zetler PJ et al, 199546 | 30/M | Abdominal pain | L | 11 | Adx | 20m, AWOD | None | Pleomorphic+ SMA/actin+ |

| Hayashi J et al, 199547 | 55/F | Abdominal pain+fever | R | N/D | Adx+Nx | 52m, AWOD | IVC+right atrium+hepatic vein | N/D |

| Lack EE et al, 199119 | 49/M | Flank pain | R | 11 | Adx+Nx; CT+RT |

9m, alive with bone metastases | None (preoperative); bone(postoperative after 3 months) | Pleomorphic+ SMA/vimentin/actin+ |

| Choi SH et al, 198148 | 50/F | Flank pain | L | 16 | Adx+partial Nx | 12m, AWOD | None | N/D |

Abbreviations: Adx, adrenalectomy; AO, adjacent organ; AWOD, alive without disease; CT, chemotherapy; EBLE, edema in both lower extremities; IVC, inferior vena cava; Lymx, lymphadenectomy; NSE, neuron-specific enolase; Nx, nephrectomy; N/D, not disclosed; PAL, primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; RT, radiation therapy; RUQ, right upper quadrant; SMA, smooth muscle actin.

Symptoms are mainly secondary to the mass effect of the tumor and local invasion. The most common presenting symptom is flank pain or abdominal pain in approximately 64% of patients. If the tumor extends into the IVC or the large tumor compresses the IVC, patients may present with IVC involvement, and experience obstructive symptoms such as lower extremity edema, spider angiomata, abdominal varices, and even altered sensation in the lower limbs.6–10 In a rarely case, the tumor ruptured suddenly, and the patient presented with severe and acute abdominal pain.11 Because tumors are located in the retroperitoneum, and are often nonfunctional, they often grow to large sizes prior to noticeable symptoms. The size of the PAL at presentation has ranged from 0.8 to 27 cm (mean, 10.2 cm), with 78.4% of tumors larger than 6 cm.

Adrenal masses detected incidentally during radiological investigations account for 4%.12 Although there are no definite features that can be used to diagnose PAL, imaging examination is useful for identifying the tumor size, location and metastasis, and evaluating its extent in relation to its surrounding structures, as well as distinguishing between potentially benign and malignant lesions. In a series of 705 patients with adrenal incidentalomas, it was demonstrated that unenhanced CT attenuation >10 and size greater than 7 cm had a high sensitivity for malignancy.13 There is a growing consensus, however, that the size should not be used to differentiate malignant from benign adrenal tumor. Modern imaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and 18F-FDG-PET represent the state of the art in adrenal imaging, which have greater sensitivity and specificity in establishing malignant versus benign diagnosis. MRI provides a more precise estimation than CT in the detection of the tumor origin and location to local structures due to its high-quality soft tissue resolution. Generally speaking, malignant masses are denser than benign masses, and often appear hyperintense on T2-weighted images on account of their higher fluid content.14 Multiplanar postcontrast imaging is also useful to evaluate the extent of vascular involvement and to distinguish tumor from bland thrombus.15 Evaluation using FDG-PET has a high sensitivity for detecting malignancy; increased FDG accumulation can be seen in all cases of PAL that performed FDG-PET. Hamada et al reported that the metastasis was detected by PET before it was found by CT.4 A core biopsy may be performed with radiological or ultrasound assistance prior to surgical resection. The current guidelines for the management of adrenal tumors recommend that the tumor should be confirmed to be hormonally inactive (in particular, a pheochromocytoma has been ruled out) prior to biopsy.16 In addition, nonfunctional primary adrenal cortical carcinoma should also be considered as a differential diagnosis prior to an adrenal biopsy because tumor seeding can take place.

There is currently no tumor marker or imaging that can aid to distinguish PAL nodules from other adrenal nodules nor is there an identified characteristic genetic rearrangement or specific endocrinological change associated with this neoplasm. The diagnosis of PAL is still completely dependent on histological and immunohistological evaluations after surgery. Histologically, retroperitoneal smooth muscle tumors containing 5 or more mitoses per 50 high power fields are classified as malignant. The presence of tumor cell necrosis is also strongly suggestive of malignancy.17 The typical histologic features of leiomyosarcomas include intersecting, sharply marginated fascicles of spindle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated and hyperchromatic nuclei. In many cases, coagulative necrosis and hemorrhage are common features. Varying degrees of nuclear hyperchromasia and pleomorphism usually manifest.15 Pleomorphic leiomyosarcomas that resemble any undifferentiated soft tissue sarcomas show moderate-to-high anaplasia as in the index cases and need a panel of immunohistochemical stains to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.18 Pleiomorphic subtypes are not uncommon with 18 known cases (45%). Some cases did not reveal pleiomorphism, but prominent atypical nuclei and bizarre giant cells were described. This implies that leiomyosarcoma should be considered in the cases of an adrenal mass with malignant spindle and pleomorphic cells; however, poor prognosis is not necessarily indicated with tumors with bizarre giant and pleomorphic cells.

Tumor cells are widely presumed to arise from the smooth muscle wall of the inferior vena cava, central adrenal vein, and its branches.19 Direct infiltration of leiomyosarcoma cells was not observed microscopically in adjacent adrenal tissue in five cases. Some findings revealed that the tumor was surrounded by a thin rim of fibrous tissue and bordered the grossly identifiable adrenal gland. Therefore, we can further confirm that leiomyosarcoma most likely arises from adrenal blood vessels but not the adrenal gland.8,20,21

Immunohistochemistry is an extremely useful tool not only for determining tumor type, but also for differentiating leiomyosarcomas from other tumors (including melanoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, mesotheliomas and other sarcomas). Conventional leiomyosarcomas show strong reactivity for smooth muscle markers such as smooth muscle actin and/or muscle specific actin in 90–95% of cases and desmin in 70–90% of cases.17 However, due to the lack of such detection in many cases of PAL, we cannot obtain reliable statistical data.

Surgical resection with wide negative margins constitutes the predominant mode of therapy,16 and has the greatest impact on survival. Since tumors are typically large at diagnosis and likely to invade the IVC, it is important to carefully resect any possibly involved tissue. It is worth noting that some patients develop pulmonary embolism after surgery, so we should strengthen this aspect of care for patients.8,22

The role of chemotherapy or radiation is not well defined. Although some reports suggested that radiation therapy could alleviate symptoms for patients with metastasis and ensure improved local control,2 the sensitivity was generally poor. Kato T et al21 performed palliative radiation therapy for the patient with cervical spine metastasis, but it showed almost no effect. Systemic chemotherapy may delay local recurrence if given as adjuvant/neoadjuvant treatment, but there are lack of randomized trial data indicating a survival benefit for patients.2 In one case reported by Lujan MG et al,23 the patient received preoperative chemotherapy, resulting in considerable reduction of the size of the lung mass; however, the adrenal mass continued to grow.

Given the rarity of the tumor, assessment of its prognosis remains difficult, but venous thrombosis, adjacent organ invasion and distant metastases were proposed to be predictors of an unfavorable outcome.7,24 A prospective study suggested that 55% of patients with leiomyosarcomas of somatic soft tissues developed metastasis or died within 3 years.25 We found that of the 40 patients, 7 died within six months. Because only limited clinical data are currently available on PAL, our data offer some important information on the clinical and therapeutic aspects of this rare disorder to increase clinician vigilance.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PAL is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm that most likely arises from the IVC, central adrenal vein and its branches. The tumors may grow to large sizes before incidental detection at imaging or palpation. Patients presenting with symptoms from these tumors might have large tumors that have invaded adjacent structures or extended into the IVC. Diagnosis in an advanced stage contributes to a poor prognosis. Surgical resection with clear margins remains the mainstay of treatment.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Yuanyuan Wang and Dr. Yongliang Teng are co-first authors for this study.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, People’s Republic of China), and was permitted to be published. Written informed consent to have the case details and accompanying images published was obtained from the patient. All clinical investigations were conducted in accordance with the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Serrano C, George S. Leiomyosarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013;27(5):957–974. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bathan AJ, Constantinidou A, Pollack SM, Jones RL. Diagnosis, prognosis, and management of leiomyosarcoma: recognition of anatomic variants. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25(4):384–389. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3283622c77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mankin HJ, Casas-Ganem J, Kim JI, Gebhardt MC, Hornicek FJ, Zeegen EN. Leiomyosarcoma of somatic soft tissues. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;421(421):225–231. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000119250.08614.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamada S, Ito K, Tobe M, et al. Bilateral adrenal leiomyosarcoma treated with multiple local therapies. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14(4):356–360. doi: 10.1007/s10147-008-0844-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linos D, Kiriakopoulos AC, Tsakayannis DE, Theodoridou M, Chrousos G. Laparoscopic excision of bilateral primary adrenal leiomyosarcomas in a 14-year-old girl with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Surgery. 2004;136(5):1098–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doppalapudi SK, Shah T, Fitzhugh VA, Bargman V. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma with inferior vena cava extension in a 70-year-old man. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(3):e227670. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-227670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karaosmanoglu AD, Gee MS. Sonographic findings of an adrenal leiomyosarcoma. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(9):1369–1373. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.9.1369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang TS, Ocal IT, Salem RR, Elefteriades J, Sosa JA. Leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal vein: a novel approach to surgical resection. World J Surg Oncol. 2007;5(1):109. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong C, Von Oppell UO, Scott-Coombes D. Cold feet from adrenal leiomyosarcoma. J R Soc Med. 2005;98(9):418–420. doi: 10.1177/014107680509800910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etten B, van Ijken MG, Mooi WJ, Oudkerk M, van Geel AN. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland. Sarcoma. 2001;5(2):95–99. doi: 10.1155/S1357714X01000184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui Y, Fujikawa K, Oka H, Fukuzawa S, Takeuchi H. Adrenal leiomyosarcoma extending into the right atrium. Int J Urol. 2002;9(1):54–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2002.00413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muscogiuri G, De Martino MC, Negri M, et al. Adrenal mass: insight into pathogenesis and a common link with insulin resistance. Endocrinology. 2017;158(6):1527–1532. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iñiguez-Ariza NM, Kohlenberg JD, Delivanis DA, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and radiological characteristics of a single-center retrospective cohort of 705 large adrenal tumors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;2(1):30–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mansmann G, Lau J, Balk E, Rothberg M, Miyachi Y, Bornstein SR. The clinically inapparent adrenal mass: update in diagnosis and management. Endocr Rev. 2004;25(2):309–340. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marko J, Wolfman DJ. Retroperitoneal leiomyosarcoma from the radiologic pathology archives. Radiographics. 2018;38(5):1403–1420. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018180006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European society of endocrinology clinical practice guideline in collaboration with the european network for the study of adrenal tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(2):G1–G34. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deshmukh SD, Babanagare SV, Anand M, Pande DP, Yavalkar P. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report with immunohistochemical study and review of literature. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013;9(1):114–116. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.110394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohanty SK, Balani JP, Parwani AV. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland: case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2007;70(3):591.e595. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lack EE, Graham CW, Azumi N, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of adrenal gland. Case report with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15(9):899–905. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199109000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto J, Otsuka F, Kodera R, et al. A rare tumor in the adrenal region: neuron-specific enolase (NSE)-producing leiomyosarcoma in an elderly hypertensive patient. Endocr J. 2008;55(1):175–181. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.K07E-020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thamboo TP, Liew LCH, Raju GC. Adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report and literature review. Pathology. 2003;35(1):47–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mencoboni M, Bergaglio M, Truini M, Varaldo M. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report and literature review. Clin Med Oncol. 2008;2(353–356):CMO–S627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lujan MG, Hoang MP. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127(1):e32–e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Tang Y, Tang J, Deng F, Gong G, Dai Y. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(4):4258–4263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farshid G, Pradhan M, Goldblum J, Weiss SW. Leiomyosarcoma of Somatic Soft Tissues. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26(1):14–24. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200201000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakellariou M, Dellaportas D, Grapsa E, et al. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2020. doi: 10.3892/mco.2020.1987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nerli RB, Ghagane S, Dixit NS, Hiremath MB, Deole S. Adrenal leiomyosarcoma in a young adult male. Int Cancer Conf J. 2020;9(1):14–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mulani SR, Stoner P, Schlachterman A, Ghayee HK, Lu L, Gupte A. First reported case of endoscopic ultrasound-guided core biopsy yielding diagnosis of primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2018;2018:8196051. doi: 10.1155/2018/8196051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Onishi T, Yanagihara Y, Kikugawa T, et al. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma with lymph node metastasis: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2016;14(1):176. doi: 10.1186/s12957-016-0936-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quildrian S, Califano I, Carrizo F, Daffinoti A, Calónico N. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma treated by laparoscopic adrenalectomy. Endocrinol Nutr. 2015;62(9):472–473. doi: 10.1016/j.endonu.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagaraj V, Mustafa M, Amin E, Ali W, Naji Sarsam S, Darwish A. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma in an arab male: a rare case report with immunohistochemistry study. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:702541. doi: 10.1155/2015/702541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei J, Sun A, Tao J, Wang C, Liu F. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Pathol. 2014;22(8):722–726. doi: 10.1177/1066896914526777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oztürk H. Vena cava invasion by adrenal leiomyosarcoma. Rare Tumors. 2014;6(2):5275. doi: 10.4081/rt.2014.5275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee S, Tanawit GDC, Lopez RA, Zamuco JT, Cheng BGG, Siozon MV. Primary leiomyosarcoma of adrenal gland with tissue eosinophilic infiltration. Korean J Pathol. 2014;48(6):423–425. doi: 10.4132/KoreanJPathol.2014.48.6.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gulpinar MT, Yildirim A, Gucluer B, et al. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland: a case report with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Case Rep Urol. 2014;2014:489630. doi: 10.1155/2014/489630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bhalla A, Sandhu F, Sieber S. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Conn Med. 2014;78(7):403–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alam MM, Naser MF, Islam MF, Rahman MA. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma in an adult female. Mymensingh Med J. 2014;23(2):380–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shao IH, Lee W-C, Chen T-D, Chiang Y-J. Leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal vein. Chang Gung Med J. 2012;35(5):428–431. doi: 10.4103/2319-4170.105475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu SV, Lenkiewicz E, Evers L, et al. Genomic analysis and selected molecular pathways in rare cancers. Phys Biol. 2012;9(6):065004. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/9/6/065004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanthan R, Senger J-L, Kanthan S. Three uncommon adrenal incidentalomas: a 13-year surgical pathology review. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Laarhoven HWM, Vinken M, Mus R, Flucke U, Oyen WJG, Van der Graaf WT. The diagnostic hurdle of an elderly male with bone pain: how 18F-FDG-PET led to diagnosis of a leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland. Anticancer Res. 2009;29(2):469–472. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee CW, Tsang YM, Liu KL. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31(1):123–124. doi: 10.1007/s00261-005-0343-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Candanedo-González FA, Vela Chávez T, Cérbulo-Vázquez A. Pleomorphic leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland with osteoclast-like giant cells. Endocr Pathol. 2005;16(1):75–81. doi: 10.1385/EP:16:1:075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kato T, Kato T, Sakamoto S, et al. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma with inferior vena cava thrombosis. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004;9(3):189–192. doi: 10.1007/s10147-004-0383-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boman F, Gultekin H, Dickman PS. Latent Epstein-Barr virus infection demonstrated in low-grade leiomyosarcomas of adults with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, but not in adjacent Kaposi’s lesion or smooth muscle tumors in immunocompetent patients. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121(8):834–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zetler PJ, Filipenko JD, Bilbey JH, Schmidt N. Primary adrenal leiomyosarcoma in a man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Further evidence for an increase in smooth muscle tumors related to Epstein-Barr infection in AIDS. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119(12):1164–1167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hayashi J, Ohzeki H, Tsuchida S, et al. Surgery for cavoatrial extension of malignant tumors. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;43(3):161–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi SH, Liu K. Leiomyosarcoma of the adrenal gland and its angiographic features: a case report. J Surg Oncol. 1981;16(2):145–148. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930160205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]