Abstract

Development of medications selective for dopamine D2 or D3 receptors is an active area of research in numerous neuropsychiatric disorders including addiction and Parkinson’s disease. The positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO, an agonist that binds with high affinity to both D2 and D3 receptors, has been used to estimate relative receptor subtype occupancy by drugs based on a priori knowledge of regional variation in the expression of D2 and D3 receptors. The objective of this work was to use a data-driven independent component analysis (ICA) of receptor blocking scans to separate D2- and D3-related signal in [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding data in order to improve the precision of subtype specific measurements of binding and occupancy. Eight healthy volunteers underwent [11C](+)-PHNO PET scans at baseline and at two time points following administration of the D3-preferring antagonist ABT-728 (150–1000 mg). Parametric binding potential (BPND) images were analyzed as four-dimensional image series using ICA to extract two independent sources of variation in [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND. Spatial source maps for each component were consistent with respective regional patterns of D2- and D3-related binding. ICA-derived occupancy estimates from each component were similar to D2- and D3-specific occupancy estimated from a region-based approach (intraclass correlation coefficients > 0.95). ICA-derived estimates of D3 receptor occupancy improved quality of fit to a single site binding model. Furthermore, ICA-derived estimates of the regional fraction of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding related to D3 receptors was generated for each subject and values showed good agreement with region-based model estimates and prior literature values. In summary, ICA successfully separated D2- and D3-related components of the [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding signal, establishing this approach as a powerful data-driven method to quantify distinct biological features from PET data composed of mixed data sources.

Keywords: dopamine, D3 receptors, positron emission tomography, independent component analysis, receptor occupancy

1. Introduction

Dopamine transmission is a critical component of neural circuits controlling motor function, motivation, and reward. Impaired dopamine function is linked to disorders including Parkinson’s disease, addiction, and schizophrenia, and altered expression or activity of dopamine D2- and D3-type receptors is a common feature in these disorders. D2 receptors are densely and widely expressed in the striatum. Expression of D3 receptors is lower and more spatially restricted, with concentrations highest in midbrain nuclei, moderate in ventral striatum and pallidum, and low in dorsal striatum (Gurevich and Joyce, 1999; Murray et al., 1994; Piggott et al., 1999). Along with differential expression, growing evidence indicates that D2 and D3 receptors play distinct roles in disease. In substance use disorders, pre-clinical and clinical studies suggest that D2 binding is typically reduced but D3 binding is increased (Boileau et al., 2015, 2012; Le Foll et al., 2005; Martinez et al., 2004; Matuskey et al., 2015; Neisewander et al., 2004; Payer et al., 2014; Staley and Mash, 1996; Volkow et al., 2007, 1997, 1990; Worhunsky et al., 2017). The opposite pattern has been observed in Parkinson’s disease (Boileau et al., 2009; Payer et al., 2016). In schizophrenia, where D2 antagonists have long been a mainstay for treatment of positive symptoms, D3 receptors are emerging as a potential target for treatment of the negative and cognitive symptoms (Girgis et al., 2016; Sokoloff and Le Foll, 2017). Research in these areas would be enhanced by the ability to measure D2 and D3 receptors separately in vivo.

The positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer [11C]-(+)-4-propyl-3,4,4a,5, 6, 10 b-hexahydro-2Hnaphtho[1,2-b][1,4]oxazine-9-ol ([11C]-(+)-PHNO) (Willeit et al., 2006) allows quantification of D2/D3 receptor binding availability in vivo. In contrast to the other commonly used PET tracers for dopamine receptors such as [11C]raclopride and [18F]fallypride, [11C]-(+)-PHNO binds with markedly higher affinity to D3 than D2 receptors (Gallezot et al., 2014; Narendran et al., 2006; Rabiner et al., 2009) and provides a strong signal in both D3- and D2-rich regions. In regions of mixed D2 and D3 expression such as ventral striatum (VS), [11C]-(+)-PHNO specific binding represents a sum of D2 and D3 receptor availability weighted by its relative affinity (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011). Given these properties, [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET has been a valuable tool to assess receptor occupancy and subtype selectivity of existing and emerging dopaminergic drugs (Di Ciano et al., 2019; Girgis et al., 2016, 2015; Graff-Guerrero et al., 2010, 2009; Le Foll et al., 2016; Mizrahi et al., 2011; Mugnaini et al., 2013; Searle et al., 2013; Tateno et al., 2018; Tziortzi et al., 2011). These estimates typically involve comparing displacement of tracer binding in D2- or D3-rich regions, with signals in the caudate or putamen commonly taken as representative of D2 binding while those in D3-expressing regions including substantia nigra (SN) or globus pallidus (GP) are generally interpreted as D3 binding. While this approach has been successful in assessing receptor selectivity broadly, regional variability can present a challenge for detailed interpretation of subtype-specific effects (Le Foll et al., 2016.; Mizrahi et al., 2011).

Independent component analysis (ICA) is a data-driven method used to identify multiple sources of variance in a dataset, ‘unmixing’ observed signals into maximally independent components. We recently performed a study using ICA to investigate [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding in individuals with cocaine use disorder and healthy controls (Worhunsky et al., 2017). Without a priori information, ICA identified components of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding with spatial sources that were similar to dopaminergic pathways and closely followed known patterns of D2 and D3 receptor distribution. This analysis concurrently replicated the opposing changes in D2- and D3-related binding previously observed only in separate regions in studies of substance use disorders. While this initial finding suggests that ICA-derived components represent distinct estimates of D2- and D3-related binding, [11C]-(+)-PHNO blocking studies with selective compounds would provide stronger evidence for subtype specificity of ICA components.

In brain imaging, ICA has been used to identify components of within-subjects spatiotemporal variance in functional magnetic resonance imaging (e.g., resting-state functional brain networks) (Calhoun et al 2001; Allen et al 2011) or components of between-subject spatial variance in cross-sectional PET study designs (Di et al., 2012; Pagani et al., 2016). The objective of the present study was to assess the utility of applying four-dimensional ICA to a competition binding PET study for the estimation of subtype-specific receptor occupancy. ICA results from a [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET study with the D3 antagonist ABT-728 were compared to traditional region-of-interest (ROI)-based estimates of local D2 and D3 binding concentrations, receptor occupancies, regional fractions of D3 receptor binding, and concentration-occupancy curves and EC50. We hypothesized that such an approach would improve the precision of these estimates by using data from the entire brain rather than a few selected regions.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

Eight healthy male volunteers (mean age 33±11 years) were scanned with [11C]-(+)-PHNO at baseline. Participants were then administered a single oral dose of the D3-specific antagonist ABT-728 (150 mg, n=1; 500 mg, n=3; 1000 mg, n=4), which has 134-fold greater affinity for D3 receptors over D2 and >600-fold higher affinity over D1 and D4 receptors in vitro. Post-drug scans were performed at approximately 2 hours post-dose (mean 2.2±0.14 h) and again at approximately 24 hours post-dose (mean 22.5 ± 2.2 h), for a total of three scans per subject. For one subject the second blocking scan was performed at 8.1 h post-dose. Plasma concentration of ABT-728 was measured in venous blood samples drawn at 60, 90, and 120 minutes after tracer injection and mean plasma drug concentration was determined for each scan.

2.2. [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET scans

[11C]-(+)-PHNO was prepared as previously described (Gallezot et al., 2014; Wilson et al., 2005). Dynamic PET data were acquired for 120 minutes on a Siemens high-resolution research tomograph (HRRT; Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN, USA). Head motion was tracked using an optical detector (Vicra, NDI Systems, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada). A T1-weighted anatomical MR image was collected for each participant using a Siemens 3T Trio system (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA) and standard magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) sequence (repeat time (TR)/echo time (TE)=2530/3.34, flip angle=7°, in-plane resolution=0.98x0.98 mm, matrix=256x256, slice thickness=1 mm, slices=176).

PET data were reconstructed with corrections for attenuation, normalization, scatter, randoms, deadtime and motion using the MOLAR algorithm (Carson et al., 2003), resulting in reconstructed image resolution of ~3 mm. Parametric whole-brain images of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND were computed using a simplified reference tissue model (SRTM2, Wu and Carson, 2002) with the cerebellum as reference (Gallezot et al., 2014). Spatial processing of parametric images was performed using SPM12 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK). A summed [11C]-(+)-PHNO uptake (0–10 min post-injection) image was created from the motion-corrected PET data for each scan session and rigidbody registered to the subject’s MR image. Nonlinear registration of the MR image to MNI152 space was determined using optimized unified segmentation (Ashburner and Friston, 2005). The combined linear and nonlinear registrations were applied to the parametric BPND images and smoothed with a 4 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel.

2.3. Independent Component Analysis

Four-dimensional ICA was performed on the parametric images of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND using the Group ICA of fMRI Toolbox (GIFT; http://trendscenter.orgsoftware/gift/) (Calhoun et al., 2001). The three parametric images for each subject were entered into ICA as the fourth dimension (usually the time dimension for fMRI analysis). The average BPND values across all 24 scans was used to define a mask at BPND > 0.3 to constrain the analysis to voxels of interest. The average BPND values across all 24 scans was used to define a mask at BPND > 0.3 to constrain the analysis to voxels of interest. The global mean within the mask was removed from each scan to facilitate component extraction while preserving original BPND scaled units in the identified solution.. The mean number of maximally independent components present in each subject’s time series was determined to be two using a minimum description length criterion (Li et al., 2007). Data from all subjects were concatenated into a single group and reduced to three components using principal component analysis prior to extracting the two independent components using the Infomax algorithm (Bell and Sejnowski, 1995). ICA was iterated 25 times using ICASSO to assess stability of extracted components and determine the most reliable extraction for the final output (Himberg et al., 2004).

ICA identifies components of coherent variance, consisting of loading values for each subject at each scan for each of the M components (; M = 1,2; i = 1, …,8; t =1,2,3), where A denotes the estimate of these loading values, the unknown mixing matrix (i.e. the inverse of ICA-derived un-mixing matrix). Note that the scan loadings also incorporate the PCA-reduction factor and are more accurately characterized as (R × A), but here we use to represent the final ICA-derived loading parameters. ICA also produces maps of the spatial source intensities of each component (yM). Scan loading values and spatial source maps are related to the original data in such a way that an approximation () of the original BPND data (x) can be reconstructed as the sum of their products (e.g., ) and the global mean value for each scan ():

| #(1) |

2.4. ROI analyses

Seven bilateral ROIs frequently used in [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET studies were examined: dorsal caudate (DCA), dorsal putamen (DPU), ventral pallidum (VP), GP, VS, hypothalamus (HY), and SN. ROIs were defined as in earlier work (Worhunsky et al., 2017) according to previously described guidelines (Mawlawi et al., 2001; Tziortzi et al., 2011): DCA, DPU and VS ROIs from FSL (Oxford Centre for Functional MRI of the Brain, Oxford, UK); GP, HY, and VP manually defined on the ICBM-MNI52 template (Montreal Neurological Institute, Montreal, Canada); and SN ROI manually drawn on a groupaverage parametric [11C] -(+)-PHNO BPND image from an independent sample (Gallezot et al., 2014).

ROI masks were applied to individual smoothed parametric BPND images in standard space to determine mean [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND in each region. To examine the contribution of each identified component to the total estimated in a given brain region, mean regional intensity of each spatial source map (yM) was extracted from each of the seven ROIs. These values were multiplied by scan loading values to generate component-specific partial values for each source, scan and ROI (i.e., regional ).

The regional partial values of each ICA component were compared with regional D2- and D3-related BPND calculated using literature proportions of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND as previously (Worhunsky et al., 2017). Briefly, regional BPND values were multiplied by the average published estimates of the fraction of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND reflecting D2- and D3-related specific binding respectively (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011) to produce and . Pearson correlations were assessed between and and the mean baseline partial values for each component.

2.5.1. Region-based model for receptor occupancy and fD3

For comparison with ICA results (see below), D2- and D3-specific occupancy (rD2 and rD3) were estimated using a model-based approach and ROI BPND values, assuming constant occupancy across the brain.

Apparent overall occupancy by a D3 antagonist will vary with the proportion of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding attributable to D3 receptors. To estimate receptor-specific occupancy, r, total apparent occupancy was computed from BPND in each region:

| #(2) |

Total BPND during blocking scans comprises available (unblocked) D2 and D3 receptors:

| #(3) |

where fD2 and fD3 are the fractions of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding attributable to D2 and D3 receptors in a given region (fD2 + fD3 = 1). D2 and D3 receptor occupancy during each blocking scan are therefore related to regional apparent occupancy according to:

| #(4) |

Based on prior [11C]-(+)-PHNO blocking studies (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011), it was assumed that fD3 = 1 in SN and fD3 = 0 in DPU. This model was fitted to the seven ROIs simultaneously to produce estimates of rD2, rD3, and fD3in the five remaining regions. Models were fitted separately for each subject using data from the early blocking scan and the constraints 0 ≤ r ≤ 0100% and 0 ≤ fD3 ≤ 1. In late scans, limited range of occupancies (<25% at D2 receptors) made the full model estimation unstable and so regional fD3 values were fixed to the value from each subject’s early scan and only rD2 and rD3 were estimated.

2.5.2. ICA-derived receptor occupancy and fD3

ICA loading values are estimates of the contribution from each component to the total in a given scan. Source maps provide voxel-wise spatial information that is constant across scans and subjects. Scan loading values can therefore be compared directly between baseline and blocking scans to determine how each independent source of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding is influenced by the blocking drug. Therefore, component-specific occupancy measures were calculated from the loading values as:

| #(5) |

Concordance between region-based and ICA-derived occupancy estimates was assessed by computing intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) using a two-way mixed effects model for absolute agreement of individual values (Koo and Li, 2016; Shrout and Fleiss, 1979).

From ICA results, the fraction of [11C]-(+)-PHNO signal attributable to D3 receptor binding in a given region or voxel can be calculated if the fraction of D3 binding in each component is known, i.e., for each subject, this is the sum of D3-related portion of information in each component and in the global mean BPND value (i.e., ), relative to overall ICA-reconstructed :

| #(6) |

Based on results from the blocking studies (see below), it was determined that one component (IC1) represented only D2-related binding and the other (IC2) only D3-related binding: and . To estimate , the fraction of global mean BPND representing D3 receptor binding, occupancy estimates for each component were taken to represent respective D2- and D3-receptor occupancy. As with region-based analyses described above (eq. 4), global mean BPND comprises a mixture of D2 and D3 receptor binding, and so percent change during blocking represents a weighted sum of D2 and D3 receptor occupancy. Therefore, was estimated by fitting the following equation to ICA occupancy estimates from the early blocking scan and percent difference in global mean during blocking ():

| #(7) |

Regional fD3 was then calculated for each subject as outlined above (eq. 6) using mean regional spatial intensity of each source, baseline scan loading values, global mean BPND, and , estimated from equation 7. ICA-derived regional fD3 values were compared to values estimated simultaneously with receptor occupancy in region-based analyses.

2.5.3. Concentration-occupancy curves and EC50

Across subjects, concentration-occupancy curves were constructed using measured plasma drug concentrations for region-based D2- and D3-specific occupancy estimates and for each ICA component. Each curve was fitted to a single-site binding model to produce estimates of EC50, the plasma drug concentration at which 50% of each binding site is occupied. For D2 receptors, due to the limited range of measured occupancy values, models were fitted assuming maximum occupancy of 100% and estimating only EC50. For D3 receptors, EC50 and maximum percent occupancy (≤100%) were estimated. Root mean square error (RMSE) of each curve fit was used to assess goodness of fit. Data from early and late blocking scans were analyzed together assuming a direct relationship between measured plasma drug concentration and brain occupancy.

3. Results

3.1. PET scan parameters

There were no differences between scans in [11C]-(+)-PHNO molar activity (438 ± 111 MBq at baseline, 498 ± 132 MBq at early blocking scan, 492 ± 137 MBq at late blocking scan; F2,20=0.54, p=0.59) or injected mass (0.028 ± 0.0042 μg/kg at scan 1, 0.029 ± 0.00067 μg/kg at early blocking scan, 0.027 ± 0.0056 μg/kg at late blocking scan; F2,14=1.2, p=0.32; within-subjects comparisons between scans p’s>0.14, uncorrected).

3.2. ICA-identified components of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding

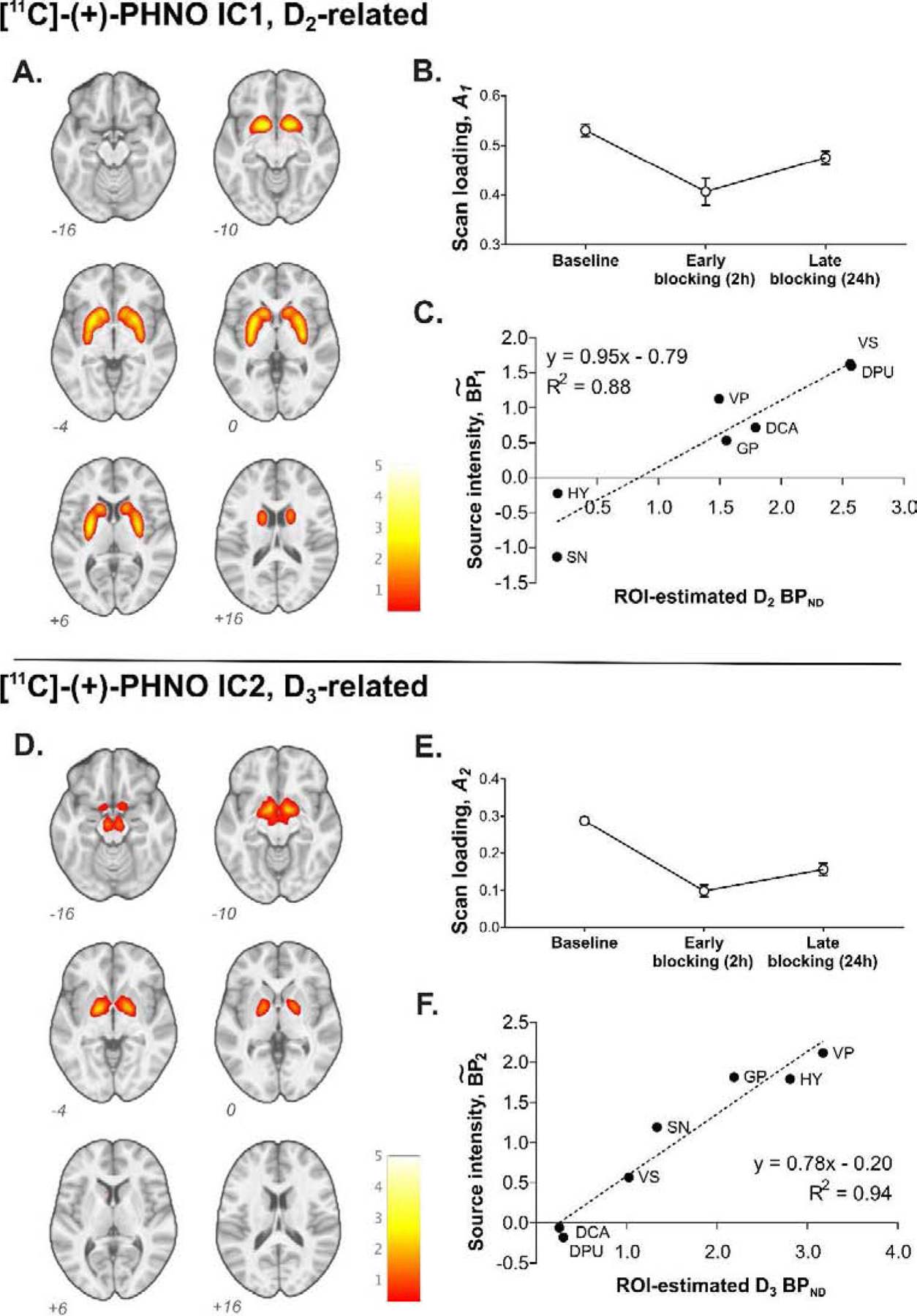

Two independent components of coherent variation in [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding across the three time points were identified (Figure 1). The source of component 1 (IC1) comprised binding in the DCA, DPU, VS, and GP, while the source of component 2 (IC2) included binding in GP, VP, SN, and HY. The source intensity patterns and partial values were consistent with the expected distribution pattern of D2- and D3-related [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011), with mean regional contributions for IC1 () correlating with estimated (r = 0.94, p=0.0018) and contributions for IC2 () correlating with (r = 0.97, p=0.00035) across the seven ROIs. No such relationship was observed in the converse pairs, i.e. with or with .

Figure 1.

ICA-identified components of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND. A and D, Source maps of IC1 (A) and IC2 (D) thresholded at ICA-estimated ; B and E, mean (± S.E.M.) scan loading values for each source in baseline, early blocking, and late blocking scans; C and F, correlation between literature-based estimates (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011; see text) of D2-related BPND and IC1 (C) and D3-related BPND and IC2 (F) across regions.

3.3. ABT-728 occupancy

3.3.1. Region-based estimates.

Using an occupancy model and change in ROI BPND values, overall occupancy of D3 receptors at two hours post-drug was 26% with a dose of 150 mg (n=1), 63 ± 7.4% with 500 mg, and 69 ± 3.3% with 1000 mg. Corresponding occupancy at D2 receptors was 0%, 20 ± 3.4%, and 31 ± 8.6%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Estimated occupancy in [11C]-(+)-PHNO blocking scans using ICA and regional analyses.

| Subject | Dose (mg) | Blocking scan | Plasma concentration ABT-728 (μg/mL) | Occupancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional BPND | ICA | ||||||

| D2 | D3 | IC1 | IC2 | ||||

| 1 | 150 | 1 | 3.4 | 0.0% | 26% | −1.6% | 32% |

| 2 | 1.0 | 0.0% | 2.7% | −3.8% | 6.9% | ||

| 2 | 500 | 1 | 11.0 | 17% | 64% | 15% | 60% |

| 2 | 8.1 | 23% | 66% | 21% | 59% | ||

| 3 | 500 | 1 | 12.0 | 22% | 69% | 21% | 66% |

| 2 | 4.5 | 3.8% | 39% | 3% | 36% | ||

| 4 | 500 | 1 | 11.8 | 23% | 55% | 21% | 57% |

| 2 | 3.7 | 9.7% | 38% | 8% | 34% | ||

| 5 | 1000 | 1 | 19.7 | 28% | 65% | 30% | 79% |

| 2 | 7.4 | 15% | 49% | 14% | 56% | ||

| 6 | 1000 | 1 | 25.2 | 25% | 68% | 25% | 71% |

| 2 | 8.2 | 12% | 54% | 9% | 55% | ||

| 7 | 1000 | 1 | 25.2 | 44% | 73% | 45% | 85% |

| 2 | 8.5 | 15% | 50% | 16% | 57% | ||

| 8 | 1000 | 1 | 20.1 | 29% | 70% | 31% | 76% |

| 2 | 8.7 | 12% | 56% | 13% | 58% | ||

Region-based occupancy values were estimated by fitting a model (eq. 4) to regional BPND values in baseline and blocking scans. ICA-based occupancy values are percent difference from baseline to blocking scans in loading value for each component, IC1 and IC2. See text for details.

3.3.2. ICA-based estimates.

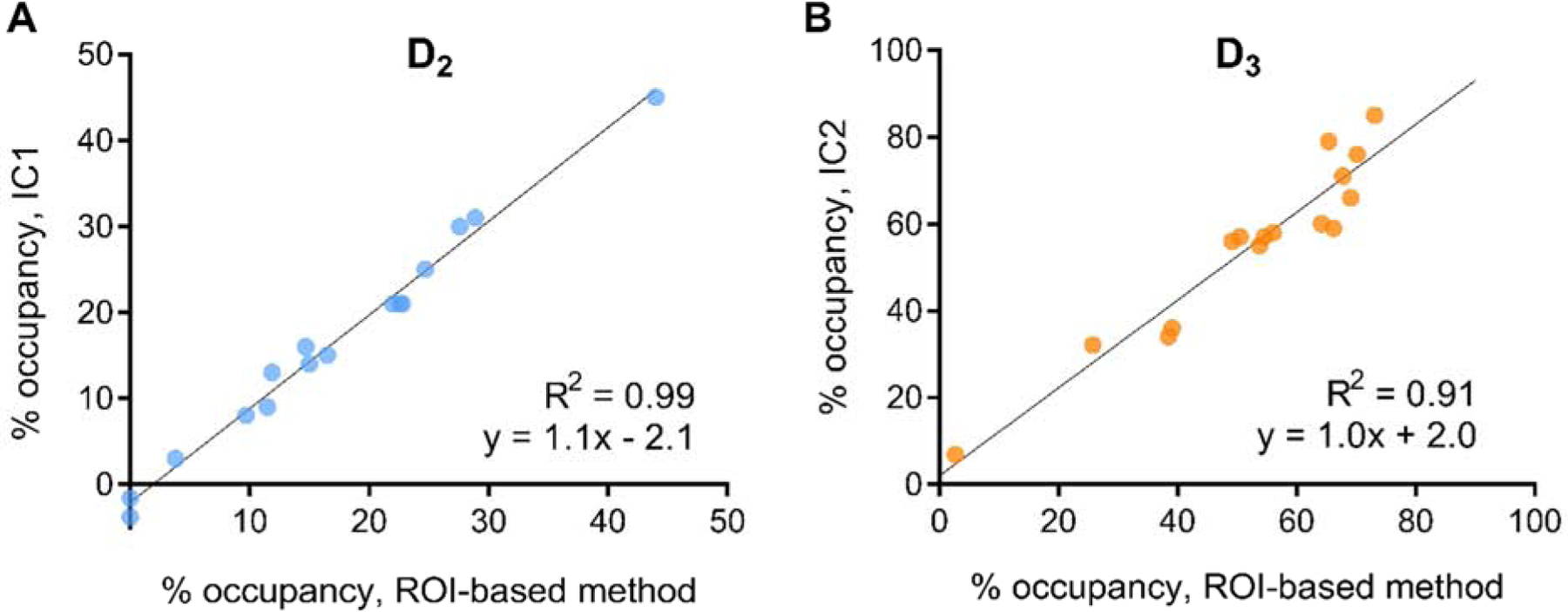

Scan loading values for IC2 were markedly reduced during blocking, with a smaller magnitude of change in IC1. At two hours post-dose, occupancy in IC2 was 32% with 150 mg, 61 ± 4.5% with 500 mg, and 78 ± 5.8% with 1000 mg; corresponding values for IC1 were −2%, 19 ± 3.7%, and 33 ± 5.3% (Table 1). Across subjects, IC1 occupancy values were closely matched to region-based estimates of occupancy at D2 receptors (ICC=0.98) and IC2 occupancy to occupancy at D3 receptors to (ICC=0.95) (Figure 2). Altogether, spatial source patterns of each component and occupancy analyses strongly support the interpretation that IC1 corresponds to D2-related binding in overall [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND and IC2 to D3-related binding. Note that ICA extracted this pattern with no a priori information.

Figure 2.

Relationship between ROI-based estimates of D2 receptor occupancy and IC1 occupancy from ICA (A) and between ROI-based D3 receptor occupancy and IC2 occupancy (B).

3.4. Regional proportion of D3 binding

3.4.1. Region-based estimates.

Regional fD3 values estimated simultaneously with receptor occupancy in region-based analyses are shown in Table 2. From this method, mean fD3 was 0.74 ± 0.17 in HY, 0.59 ± 0.087 in GP, 0.56 ± 0.14 in VP, 0.24 ± 0.057 in VS, and 0.068 ± 0.073 in DCA.

Table 2.

Regional fD3 estimated from ROI BPND values and from ICA.

| SN | HY | VP | GP | VS | DCA | DPU | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| subj | region | ICA | region | ICA | region | ICA | region | ICA | region | ICA | region | ICA | region | ICA |

| 1 | Fixed to 1 | 0.91 | 1.00 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.51 | 0.23 | 0.19 | <10−8 | 0.04 | Fixed to 0 | −0.010 |

| 2 | 0.89 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.59 | 0.24 | 0.26 | <10−8 | 0.13 | 0.047 | ||

| 3 | 0.96 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.57 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.012 | ||

| 4 | 0.92 | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.022 | ||

| 5 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.61 | 0.80 | 0.47 | 0.70 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.10 | 0.02 | −0.028 | ||

| 6 | 0.87 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.54 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.02 | −0.024 | ||

| 7 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 0.72 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.49 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.0089 | ||

| 8 | 0.91 | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.03 | −0.022 | ||

| mean | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.66 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.068 | 0.056 | -0.0018 | ||

| S.D. | 0.044 | 0.17 | 0.043 | 0.14 | 0.033 | 0.087 | 0.037 | 0.057 | 0.031 | 0.073 | 0.039 | 0.026 | ||

SN, substantia nigra; HY, hypothalamus; VP, ventral pallidum; GP, globus pallidus; VS, ventral striatum; DCA, dorsal caudate; DPU, dorsal putamen.

3.4.2. ICA-based estimates.

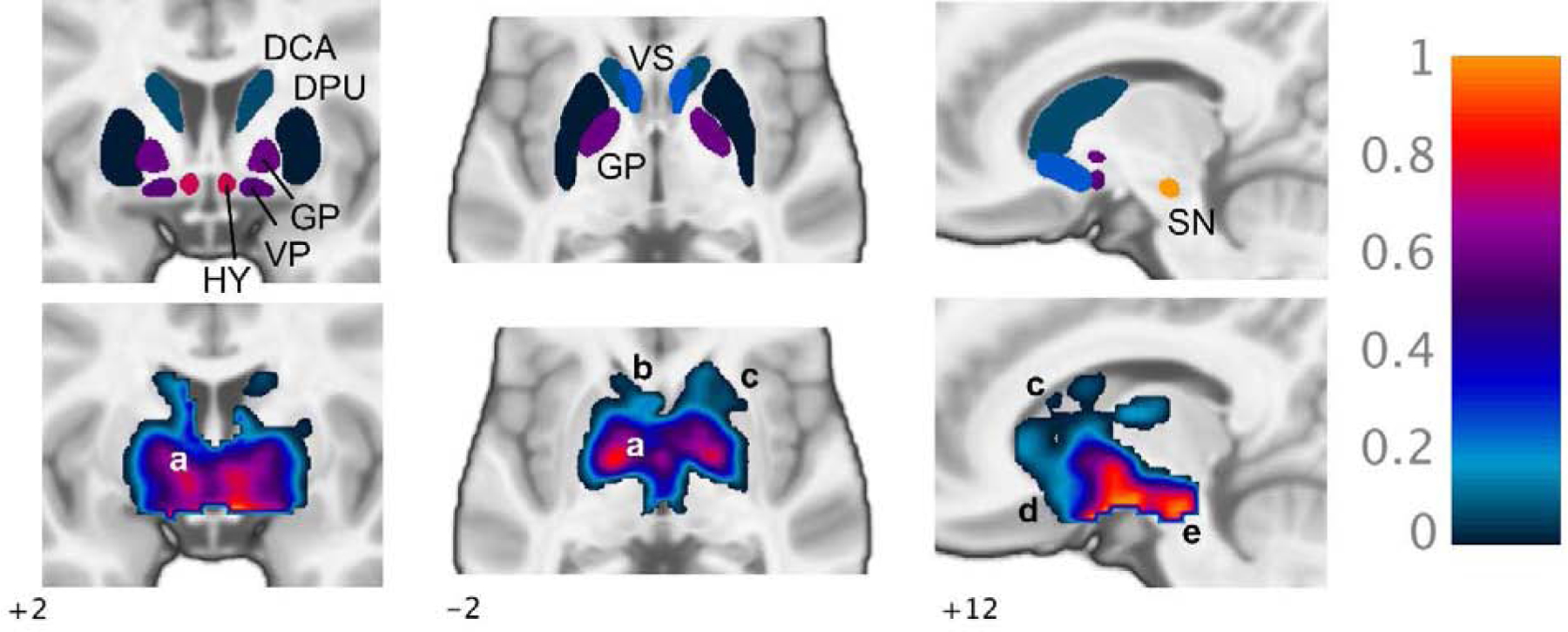

Regional fD3 was also computed from ICA results using the apparent evidence that IC1 and IC2 represent [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding to D2 and D3 receptors, respectively (i.e., and ). Thus, D3-related binding was calculated as the sum of regional (i.e., from IC2) and D3-specific binding in the global mean. Regional fD3 values for each subject are presented in Table 2. Mean fD3 was 0.92 ± 0.079 in SN, 0.66 ± 0.043 in HY, 0.53 ± 0.037 in GP, 0.49 ± 0.033 in VP, 0.21 ± 0.031 in VS, 0.56 ± 0.039 in DCA, and −0.002 ± 0.026 in DPU (Figure 3, top row). In all regions, ICA-derived fD3 values were in good agreement with region-based estimates, with a tendency to be slightly lower (Table 2). ICA estimates were markedly less variable across subjects compared to region-based fD3, with a coefficient of variation ranging from 3.5% in HY to 8.4% in DCA for ICA and from 13.7% in GP to 108% in DCA for region-based values. Mean values from both methods were consistent with group-level regional fD3 estimates from previous studies (Searle et al., 2013; Tziortzi et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

ICA-derived fraction of [11C]-(+)-PHNO signal representing D3 binding (fD3), mean of eight subjects. Top row, fD3 estimates displayed uniformly in each ROI (see Table 2). Bottom row, voxel-wise fD3 maps showing voxel-level variation in D3 binding proportion within masked region of mean BPND>0.3: a, varying fD3 within GP following a decreasing internal-external gradient; b, low fD3 in DCA and DPU increasing into VS; c, overall decreasing rostral-caudal gradient within DCA and DPU; d, increasing rostral-caudal gradient within VS; e, high fD3 within SN. DCA, dorsal caudate; DPU, dorsal putamen; GP, globus pallidus; VP, ventral pallidum; HY, hypothalamus; VS, ventral striatum; SN, substantia nigra.

A voxel-wise map of mean fD3 across subjects is shown in Figure 3 (bottom row), demonstrating varied proportion of D3-related binding within GP, low fD3 in DCA and DPU with values increasing into the VS, and high D3 binding proportion in SN. Variation within regions followed patterns similar to those identified in prior [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET and post-mortem studies (Gurevich and Joyce, 1999; Murray et al., 1994; Tziortzi et al., 2011). For example, the proportion of D3 binding appeared to be higher in the internal compared to external segment of the GP (bottom left and center panels, a) and followed an increasing rostral to caudal gradient in GP and VS but an overall decreasing rostral-caudal gradient in dorsal striatum (bottom center and right, b-d).

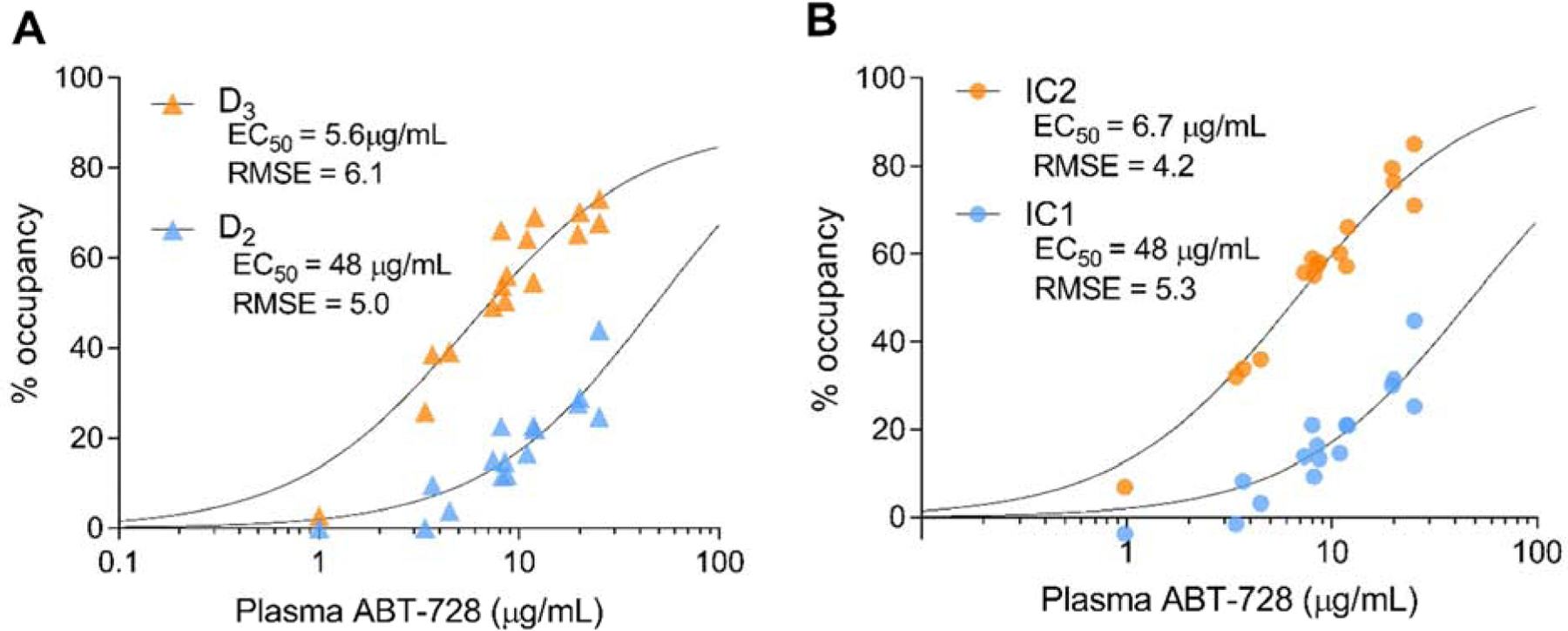

3.5. Concentration-occupancy relationships

Concentration-occupancy curves were produced for both region-based D2 and D3 estimates (Figure 4A) and ICA-identified components of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding (Figure 4B). ABT-728 EC50 estimates (Table 3) were similar between region-based D2 occupancy and IC1 (D2, 48 μg/mL SE 8.5; IC1, 48 μg/mL SE 9.0) and between D3 occupancy and IC2 (D3, 5.6 μg/mL SE 2.6; IC2, 6.7 μg/mL SE 2.0). Thus, EC50 was approximately 7-fold lower for D3 compared to D2 receptors. This is in line with in vitro studies showing higher affinity at D3 receptors, though markedly smaller than the 140-fold difference in Ki values observed in those experiments (Investigator’s Brochure, Abbott Laboratories). The phenomenon of lower selectivity in vivo has previously been noted for other D3-targeting drugs (Searle et al., 2013). For D3 receptors, estimated maximum occupancy was 89% from region-based values and 100% from IC2 (Table 3). Concentration-occupancy curve fits were qualitatively better for IC2 occupancy values than for region-based D3 occupancy estimates (RMSE 4.2 compared to 6.1; Figure 4). For D2-like binding, quality of fit was comparable for IC1 and region-based estimates (RMSE 5.3 and 5.0, respectively).

Figure 4.

ABT-728 concentration-occupancy curves. Percent occupancy from [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET scans at each plasma drug concentration for region-based D2- and D3-specific occupancy estimates (A) and for ICA-derived IC1 and IC2 occupancy (B).

Table 3.

[11C]-(+)-PHNO dose-occupancy results.

| Region-based | ICA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D2 | D3 | IC1 | IC2 | |

| EC50 (S.E.), μg/mL | 48 (8.5) | 5.6 (2.6) | 48 (9.0) | 6.7 (2.0) |

| Maximum occupancy, % | fixed to 100 | 89 (S.E. 9.0) | fixed to 100 | ~100 |

| RMSE | 5.0 | 6.1 | 5.3 | 4.2 |

RMSE, root mean square error.

4. Discussion

This study presents a novel data-driven method for assessing D2- and D3-specific binding and occupancy using four-dimensional ICA of [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET data. ICA identified two distinct components of change in binding on the basis of spatiotemporally coherent variance across subjects and time points. The respective spatial sources of these components were highly consistent with D2- and D3-related [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding distributions in the brain (Figure 1), suggesting that this analysis successfully separated binding signal specific to each receptor subtype without a priori assumptions. This interpretation is supported by relative changes in intensity of each source during blockade with the D3-selective antagonist ABT-728, which were closely matched to region-based occupancy estimates. Component loading was used to determine the proportion of D3-specific binding in the [11C]-(+)-PHNO signal across the brain, producing values consistent with those from prior literature but allowing for individual variation in D3 receptor binding contribution and visualization of this measure at the voxel level. ICA-based values of D3 occupancy improved quality of fit to a single-site concentration-occupancy model compared to region-based values, suggesting that ICA may improve precision in D3 BPND estimates by using information from a greater number of voxels.

4.1. Sources of [11C]-(+)-PHNO BPND

In a previous analysis of a separate sample of healthy volunteers and individuals with cocaine use disorder, cross-sectional spatial ICA was used to estimate three independent sources of [11C]-(+)PHNO, two of which were associated with estimated D2- or D3-specific binding (Worhunsky et al., 2017). IC1 in the present results follows a similar spatial pattern to the striatopallidal source in the earlier analysis. In both cases, regional source-specific (here, ) was correlated with estimated D2-related BPND. Similarly, IC2 here resembles the pallidonigral source in the previous study, and source-specific contributions for both were associated with D3-related BPND. Thus, qualitatively similar sources linked to the same biological features were extracted in two independent samples composed of different data types (previously, patients and healthy controls; here, baseline and blocking scans in healthy volunteers) and using different ICA approaches (previously spatial ICA; here, spatiotemporal ICA). These data strongly support the utility of ICA to identify distinct D2- and D3-related binding in [11C]-(+)-PHNO data.

4.2. Determination of D2- and D3-specific occupancy and fD3

ICA produced similar estimates of D2- and D3-specific occupancy compared to region-based analyses. Previous studies have estimated the relative D2 and D3 occupancy of new or existing medications using [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET by either comparing occupancy in regions presumed to represent D2 or D3 binding only or by fitting occupancy models as here (Di Ciano et al., 2019; Girgis et al., 2016; Graff-Guerrero et al., 2010; Mizrahi et al., 2011; Tateno et al., 2018). While these studies have produced valuable results, data-driven ICA of [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET results may improve precision by avoiding some of the challenges and confounds associated with ROI- and model-based analysis. For example, the relatively greater difficulty of delineating D3-rich regions such as the SN compared to D2-rich dorsal striatum regions may introduce bias in comparing occupancy between receptor subtypes (Le Foll et al., 2016). Indeed, concentration-occupancy curves for D3 receptors constructed with ICA-estimated values yielded qualitatively superior fits compared to region-based estimates. Thus, we propose that ICA offers a data-driven approach to estimating D3-specific binding that provides improved quantification compared to current model-based methods.

Possible limitations associated with using literature estimates of regional D3 receptor distribution were evident in the present work. For region-based analyses, it was assumed that DPU BPND reflects only D2-related binding and SN BPND only D3-related binding, as in previous [11C]-(+)-PHNO studies. However, while ICA-derived estimates of fD3 were not significantly different from zero (t=0.19, p=0.85), in SN fD3 was only approximately 0.9, i.e., not 1.0. This is remarkably similar to the estimated maximum D3 occupancy of 89% in the region-based concentration-occupancy curve, compared to 100% in the ICA-derived curve. While other biological factors may contribute to sub-maximal D3 occupancy, this observation suggests that assuming complete D3 binding in SN may introduce bias into the region-based estimates. This would account for the tendency towards slightly higher fD3 estimates across regions with the region-based approach (Table 2).

To determine if region-based results could be improved by avoiding assumptions of pure subtype binding in SN and DPU, we also fitted the occupancy model (eq. 4) to the seven ROIs estimating fD3 for all ROIs (as well as rD2 and rD3), rather than fixing fD3 in SN and DPU and estimating this parameter in only the remaining five regions. This produced fD3 estimates in mixed regions that were frequently inconsistent with literature estimates, particularly in GP (lower than expected) and in DCA and VS (higher than expected) (Supplemental Table 1), and worse fits to a concentration-occupancy model for D2 receptors. We therefore conclude that results from the unconstrained model are less likely to be accurate, despite possible bias in the primary analysis. By comparison, ICA occupancy estimates, in addition to providing greater precision, do not rely on prior knowledge or assumptions about receptor distribution patterns and so avoid this issue. Notably, this potential source of bias may be exaggerated in disease populations with altered D2 or D3 receptor expression.

4.3. Heterogeneity in fD3

Beyond occupancy, independent assessment of D2- and D3-related binding may have applications in studies aiming to understand disease and treatment mechanisms. Recent work has identified patterns of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding in Parkinson’s disease and schizophrenia that suggest differential D2/D3 changes, spatially restricted disease/treatment effects, or both (Mizrahi et al., 2011; Payer et al., 2016). Such overlapping effects are difficult to characterize conclusively with ROI-based analyses but could be determined by examining independent sources of binding. Further research is necessary to explore these possibilities and assess the sensitivity of ICA-derived measures to differences in the relative levels and spatial patterns of D2 and D3 receptor binding in patient populations, though our previous work is encouraging in this respect (Worhunsky et al., 2017).

At the voxel level, a previous study (Tziortzi et al., 2011) generated images of D2- and D3-related specific binding by [11C]-(+)-PHNO using two-stage estimation of an ROI-based occupancy model to produce group-level fD3 maps used to scale BPND images. The resulting and images are very similar to the respective -scaled source maps for IC1 and IC2 (Figure 1) in spatial pattern and magnitude (accounting for global mean correction). Here, maps of fD3 (Figure 3, bottom row) were also produced from ICA results to visualize heterogeneity in receptor binding proportion within regions. This illustrates the variation in relative D2/D3 binding within structures, unobscured by variation in total BPND. These images reproduce some of the patterns previously observed in post-mortem studies, including opposing rostral-caudal gradients in DCA/DPU compared to VS and the appearance of higher relative D3 content in the internal compared to external segment of GP (Gurevitch and Joyce, 1999; Murray et al., 1994). These patterns of relative receptor binding in vivo can inform the interpretation of future [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET studies.

4.4. Use of ICA in multi-target PET

In principle, similar methods could be applied to other systems and PET tracers. It is not uncommon for PET signals to comprise binding to two closely related target sites, as with [11C]-(+)-PHNO, or to a primary target and one or more off-target sites, such as tau-binding radiotracers like [18F]AV-1451 that also have affinity for monoamine oxidase B (Murugan et al., 2019). While this seems an appealing and intuitive application of ICA, several important factors may limit the generalizability of this method. [11C](+)-PHNO is particularly well-suited to this approach since its signal represents a linear sum of binding at two sites. Radiotracers with low specific binding or target sites with highly correlated expression may not be successfully or reliably separated. The present approach using blocking studies with selective drugs, and thus different levels of occupancy at each site, might be particularly powerful in such cases. However, the maximum number of independent components that can be extracted from this method is dimensionally limited to the number of scans performed on each subject. Future studies could explore the utility of spatial (i.e., 3-dimensional) ICA in occupancy studies where more binding targets might be anticipated, fewer time points are available, or the number of time points varies across subjects. Under favorable conditions ICA could be a useful method for more precise quantification of biological features in mixed-target PET data across systems.

4.5. Limitations

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, a gold standard comparator for ICA-based occupancy estimates was not available for these analyses. Accuracy of ICA results was assessed based on agreement with region-based occupancy estimates, which have limitations as discussed above, and with literature estimates of fD3. We therefore conclude that ICA performs similarly to or better than existing methods for estimating D2 and D3 receptor occupancy. Both sets of analyses used SRTM estimates of BPND with cerebellum as reference region rather than arterial sampling with full quantification. This may not be optimal since reductions in VT in cerebellum during blocking experiments has been observed in previous studies (Rabiner et al., 2009; Searle et al., 2013), consistent with some specific binding in the reference region which would bias BPND estimates. However, SRTM-derived BPND using cerebellum reference is by far the most commonly used outcome measure in [11C]-(+)-PHNO studies, and any bias associated with this method would not be expected to affect our primary conclusion about the utility of ICA for this application. Concentration-occupancy analyses pooled scans from early and late time points post-drug, which assumes a linear relationship between drug concentration in brain and blood over time. To assess the validity of this, binding models were fit to occupancies from early and late scans separately. In each case, EC50 estimates were very similar to those from the pooled analysis in Table 3. Injected mass of PHNO could also influence occupancy estimates due to binding competition by unlabeled PHNO, particularly at higher-affinity D3 receptors (Searle et al., 2013). Applying a correction for injected mass (Gallezot et al., 2017; see Supplemental Information) did not improve variability or goodness of fits to the single-site binding model (Supplemental Table 2 and Supplemental Figure). Notably, PHNO mass influences both ROI-based and ICA-based methods, and so this does not affect our main conclusions. Given that injected mass did not differ between scans, this correction was not pursued further, but may represent a source of bias in occupancy estimates using either analysis method. Finally, as in previous analyses of D3-specific binding with [11C]-(+)-PHNO, only male subjects were included in this study. The present methods, and in vivo estimates of D3 occupancy and regional binding patterns more generally, require validation in women.

5. Conclusions.

This analysis presents successful separation of D2 and D3 receptor specific binding using ICA in a [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET study with a D3-selective drug. As development continues for drugs specifically targeting D3 receptors in neuropsychiatric disease, precise quantification of D3 receptor availability and occupancy will become increasingly important. Given the structural similarities between the two receptors, achieving high specificity for D3 over D2 receptors is a challenge in drug design and precise estimates of subtype-specific occupancy in vivo are crucial. The approach presented here may offer a powerful tool to dissect the role of D2 and D3 receptors in human brain function, disease, and treatment. More broadly, this work demonstrates the potential for ICA methods to disentangle PET signals from tracers that have mixed binding, which would facilitate a truly quantitative understanding of in vivo neurochemistry in a range of systems and clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research was funded by AbbVie Inc. and by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (K01 DA042998) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (K01 AA024788).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none.

References

- Allen EA, Erhardt EB, Damaraju E, Gruner W, Segall JM, Silva RF, Havlicek M, Rachakonda S, Fries J, Kalyanam R, Michael AM, Caprihan A, Turner JA, Eichele T, Adelsheim S, Bryan AD, Bustillo J, Clark VP, Feldstein Ewing SW, Filbey F, Ford CC, Hutchison K, Jung RE, Kiehl KA, Kodituwakku P, Komesu YM, Mayer AR, Pearlson GD, Phillips JP, Sadek JR, Stevens M, Teuscher U, Thoma RJ, Calhoun VD, 2011. A baseline for the multivariate comparison of resting-state networks. Front Syst Neurosci 5, 2 10.3389/fnsys.2011.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburner J, Friston KJ, 2005. Unified segmentation. NeuroImage 26, 839–851. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Guttman M, Rusjan P, Adams JR, Houle S, Tong J, Hornykiewicz O, Furukawa Y, Wilson AA, Kapur S, Kish SJ, 2009. Decreased binding of the D3 dopamine receptor-preferring ligand [11C]-(+)-PHNO in drug-naïve Parkinson’s disease. Brain 132, 1366–1375. 10.1093/brain/awn337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Nakajima S, Payer D, 2015. Imaging the D3 dopamine receptor across behavioral and drug addictions: Positron emission tomography studies with [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 25, 1410–1420. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Payer D, Houle S, Behzadi A, Rusjan PM, Tong J, Wilkins D, Selby P, George TP, Zack M, Furukawa Y, McCluskey T, Wilson AA, Kish SJ, 2012. Higher binding of the dopamine D3 receptor-preferring ligand [11C]-(+)-propyl-hexahydro-naphtho-oxazin in methamphetamine polydrug users: a positron emission tomography study. J. Neurosci 32, 1353–1359. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4371-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, Pekar JJ, 2001. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping 14, 140–151. 10.1002/hbm.1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson RE, Barker WC, Jeih-San Liow, Johnson CA, 2003. Design of a motion-compensation OSEM listmode algorithm for resolution-recovery reconstruction for the HRRT. IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium. Conference Record (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37515) 3281–3285. 10.1109/NSSMIC.2003.1352597 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di X, Biswal, and A.D NI, Bharat B, 2012. Metabolic Brain Covariant Networks as Revealed by FDG-PET with Reference to Resting-State fMRI Networks. Brain Connectivity 2, 275–283. 10.1089/brain.2012.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Mansouri E, Tong J, Wilson AA, Houle S, Boileau I, Duvauchelle T, Robert P, Schwartz JC, Le Foll B, 2019. Occupancy of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors by a novel D3 partial agonist BP1.4979: a [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET study in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 44, 1284–1290. 10.1038/s41386-018-0285-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallezot J-D, Planeta B, Nabulsi N, Palumbo D, Li X, Liu J, Rowinski C, Chidsey K, Labaree D, Ropchan J, Lin SF, Sawant-Basak A, McCarthy TJ, Schmidt AW, Huang Y, Carson RE, 2017. Determination of receptor occupancy in the presence of mass dose: [11C]GSK189254 PET imaging of histamine H3 receptor occupancy by PF-03654746. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 37, 1095–1107. 10.1177/0271678X16650697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallezot J-D, Zheng M-Q, Lim K, Lin S, Labaree D, Matuskey D, Huang Y, Ding Y-S, Carson RE, Malison RT, 2014. Parametric Imaging and Test–Retest Variability of 11C-(+)-PHNO Binding to D2/D3 Dopamine Receptors in Humans on the High-Resolution Research Tomograph PET Scanner. J Nucl Med 55, 960–966. 10.2967/jnumed.113.132928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis RR, Slifstein M, D’Souza D, Lee Y, Periclou A, Ghahramani P, Laszlovszky I, Durgam S, Adham N, Nabulsi N, Huang Y, Carson RE, Kiss B, Kapás M, Abi-Dargham A, Rakhit A, 2016. Preferential binding to dopamine D3 over D2 receptors by cariprazine in patients with schizophrenia using PET with the D3/D2 receptor ligand [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 233, 3503–3512. 10.1007/s00213-016-4382-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis RR, Xu X, Gil RB, Hackett E, Ojeil N, Lieberman JA, Slifstein M, Abi-Dargham A, 2015. Antipsychotic binding to the dopamine-3 receptor in humans: A PET study with [(11)C]-(+)-PHNO. Schizophr. Res 168, 373–376. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.06.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Guerrero A, Mamo D, Shammi CM, Mizrahi R, Marcon H, Barsoum P, Rusjan P, Houle S, Wilson AA, Kapur S, 2009. The effect of antipsychotics on the high-affinity state of D2 and D3 receptors: a positron emission tomography study With [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66, 606–615. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff-Guerrero A, Redden L, Abi-Saab W, Katz DA, Houle S, Barsoum P, Bhathena A, Palaparthy R, Saltarelli MD, Kapur S, 2010. Blockade of [11C](+)-PHNO binding in human subjects by the dopamine D3 receptor antagonist ABT-925. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 13, 273–287. 10.1017/S1461145709990642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich EV, Joyce JN, 1999. Distribution of Dopamine D 3 Receptor Expressing Neurons in the Human Forebrain: Comparison with D 2 Receptor Expressing Neurons. Neuropsychopharmacology 20, 60 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00066-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himberg J, Hyvärinen A, Esposito F, 2004. Validating the independent components of neuroimaging time series via clustering and visualization. NeuroImage 22, 1214–1222. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo TK, Li MY, 2016. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 15, 155–163. 10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Diaz J, Sokoloff P, 2005. A single cocaine exposure increases BDNF and D3 receptor expression: implications for drug-conditioning. Neuroreport 16, 175–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Payer D, Di Ciano P, Guranda M, Nakajima S, Tong J, Mansouri E, Wilson AA, Houle S, Meyer JH, Graff-Guerrero A, Boileau I, 2016. Occupancy of Dopamine D3 and D2 Receptors by Buspirone: A [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET Study in Humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 529–537. 10.1038/npp.2015.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-O, Adali T, Calhoun VD, 2007. Estimating the number of independent components for functional magnetic resonance imaging data. Hum Brain Mapp 28, 1251–1266. 10.1002/hbm.20359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez D, Broft A, Foltin RW, Slifstein M, Hwang D-R, Huang Y, Perez A, Frankle WG, Cooper T, Kleber HD, Fischman MW, Laruelle M, Frankel WG, 2004. Cocaine dependence and d2 receptor availability in the functional subdivisions of the striatum: relationship with cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1190–1202. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuskey D, Gaiser EC, Gallezot J-D, Angarita GA, Pittman B, Nabulsi N, Ropchan J, MaCleod P, Cosgrove KP, Ding Y-S, Potenza MN, Carson RE, Malison RT, 2015. A preliminary study of dopamine D2/3 receptor availability and social status in healthy and cocaine dependent humans imaged with [(11)C](+)PHNO. Drug Alcohol Depend 154, 167–173. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawlawi O, Martinez D, Slifstein M, Broft A, Chatterjee R, Hwang D-R, Huang Y, Simpson N, Ngo K, Van Heertum R, Laruelle M, 2001. Imaging Human Mesolimbic Dopamine Transmission with Positron Emission Tomography: I. Accuracy and Precision of D2 Receptor Parameter Measurements in Ventral Striatum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 21, 1034–1057. 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizrahi R, Agid O, Borlido C, Suridjan I, Rusjan P, Houle S, Remington G, Wilson AA, Kapur S, 2011. Effects of antipsychotics on D3 receptors: a clinical PET study in first episode antipsychotic naive patients with schizophrenia using [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Schizophr. Res 131, 63–68. 10.1016/j.schres.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugnaini M, Iavarone L, Cavallini P, Griffante C, Oliosi B, Savoia C, Beaver J, Rabiner EA, Micheli F, Heidbreder C, Andorn A, Merlo Pich E, Bani M, 2013. Occupancy of Brain Dopamine D3 Receptors and Drug Craving: A Translational Approach. Neuropsychopharmacology 38, 302–312. 10.1038/npp.2012.171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AM, Ryoo HL, Gurevich E, Joyce JN, 1994. Localization of dopamine D3 receptors to mesolimbic and D2 receptors to mesostriatal regions of human forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 91, 11271–11275. 10.1073/pnas.91.23.11271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan NA, Chiotis K, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, Lemoine L, Ågren H, Nordberg A, 2019. Cross-interaction of tau PET tracers with monoamine oxidase B: evidence from in silico modelling and in vivo imaging. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 46, 1369–1382. 10.1007/s00259-019-04305-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendran R, Slifstein M, Guillin O, Hwang Y, Hwang D-R, Scher E, Reeder S, Rabiner E, Laruelle M, 2006. Dopamine (D2/3) receptor agonist positron emission tomography radiotracer [11C]-(+)-PHNO is a D3 receptor preferring agonist in vivo. Synapse 60, 485–495. 10.1002/syn.20325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LTL, Weber SM, Coffey GP, Joyce JN, 2004. Increases in dopamine D3 receptor binding in rats receiving a cocaine challenge at various time points after cocaine self-administration: implications for cocaine-seeking behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1479–1487. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M, Öberg J, De Carli F, Calvo A, Moglia C, Canosa A, Nobili F, Morbelli S, Fania P, Cistaro A, Chiò A, 2016. Metabolic spatial connectivity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as revealed by independent component analysis. Hum Brain Mapp 37, 942–953. 10.1002/hbm.23078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer DE, Behzadi A, Kish SJ, Houle S, Wilson AA, Rusjan PM, Tong J, Selby P, George TP, McCluskey T, Boileau I, 2014. Heightened D3 dopamine receptor levels in cocaine dependence and contributions to the addiction behavioral phenotype: a positron emission tomography study with [11C]-+-PHNO. Neuropsychopharmacology 39, 311–318. 10.1038/npp.2013.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payer DE, Guttman M, Kish SJ, Tong J, Adams JR, Rusjan P, Houle S, Furukawa Y, Wilson AA, Boileau I, 2016. D3 dopamine receptor-preferring [11C]PHNO PET imaging in Parkinson patients with dyskinesia. Neurology 86, 224–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piggott MA, Marshall EF, Thomas N, Lloyd S, Court JA, Jaros E, Costa D, Perry RH, Perry EK, 1999. Dopaminergic activities in the human striatum: rostrocaudal gradients of uptake sites and of D1 and D2 but not of D3 receptor binding or dopamine. Neuroscience 90, 433–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner EA, Slifstein M, Nobrega J, Plisson C, Huiban M, Raymond R, Diwan M, Wilson AA, McCormick P, Gentile G, Gunn RN, Laruelle MA, 2009. In vivo quantification of regional dopamineD3 receptor binding potential of (+)-PHNO: Studies in non-human primates and transgenic mice. Synapse 63, 782–793. 10.1002/syn.20658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searle GE, Beaver JD, Tziortzi A, Comley RA, Bani M, Ghibellini G, Merlo-Pich E, Rabiner EA, Laruelle M, Gunn RN, 2013. Mathematical modelling of [11C]-(+)-PHNO human competition studies. NeuroImage 68, 119–132. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.11.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL, 1979. Intraclass Correlations : Uses in Assessing Rater Reliability. Psychol Bull 86, 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff P, Le Foll B, 2017. The dopamine D3 receptor, a quarter century later. Eur. J. Neurosci 45, 2–19. 10.1111/ejn.13390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Mash DC, 1996. Adaptive increase in D3 dopamine receptors in the brain reward circuits of human cocaine fatalities. J. Neurosci 16, 6100–6106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateno A, Sakayori T, Kim W-C, Honjo K, Nakayama H, Arakawa R, Okubo Y, 2018. Comparison of Dopamine D3 and D2 Receptor Occupancies by a Single Dose of Blonanserin in Healthy Subjects: A Positron Emission Tomography Study With [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol 21, 522–527. 10.1093/ijnp/pyy004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tziortzi AC, Searle GE, Tzimopoulou S, Salinas C, Beaver JD, Jenkinson M, Laruelle M, Rabiner EA, Gunn RN, 2011. Imaging dopamine receptors in humans with [11C]-(+)-PHNO: Dissection of D3 signal and anatomy. NeuroImage 54, 264–277. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J, Swanson JM, Telang F, 2007. Dopamine in Drug Abuse and Addiction: Results of Imaging Studies and Treatment Implications. Arch Neurol 64, 1575–1579. 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wolf AP, Schlyer D, Shiue C-Y, Alpert R, Dewey SL, Logan J, Bendriem B, Christman D, Hitzemann R, Henn F, 1990. Effects of chronic cocaine abuse on postsynaptic dopamine receptors. American Journal of Psychiatry 147, 719–724. 10.1176/ajp.147.6.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Gatley SJ, Hitzemann R, Chen AD, Dewey SL, Pappas N, 1997. Decreased striatal dopaminergic responsiveness in detoxified cocaine-dependent subjects. Nature 386, 830–833. 10.1038/386830a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willeit M, Ginovart N, Kapur S, Houle S, Hussey D, Seeman P, Wilson AA, 2006. High-Affinity States of Human Brain Dopamine D2/3 Receptors Imaged by the Agonist [11C]-(+)-PHNO. Biological Psychiatry 59, 389–394. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AA, McCormick P, Kapur S, Willeit M, Garcia A, Hussey D, Houle S, Seeman P, Ginovart N, 2005. Radiosynthesis and Evaluation of [11C]-(+)-4-Propyl-3,4,4a,5,6,10b-hexahydro-2H-naphtho[1,2b][1,4]oxazin-9-ol as a Potential Radiotracer for in Vivo Imaging of the Dopamine D2 High-Affinity State with Positron Emission Tomography. J. Med. Chem 48, 4153–4160. 10.1021/jm050155n [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worhunsky PD, Matuskey D, Gallezot J-D, Gaiser EC, Nabulsi N, Angarita GA, Calhoun VD, Malison RT, Potenza MN, Carson RE, 2017. Regional and source-based patterns of [11C]-(+)-PHNO binding potential reveal concurrent alterations in dopamine D2 and D3 receptor availability in cocaine-use disorder. NeuroImage 148, 343–351. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.01.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Carson RE, 2002. Noise Reduction in the Simplified Reference Tissue Model for Neuroreceptor Functional Imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 22, 1440–1452. 10.1097/01.WCB.0000033967.83623.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.