Abstract

Purpose

Most existing non-contrast-enhanced methods for abdominal MR arteriography rely on a spatially selective inversion (SSI) pulse with a delay to null both static tissue and venous blood, and are limited to small spatial coverage due to the sensitivity to slow arterial inflow. Velocity-selective inversion (VSI) based approach has been shown to preserve the arterial blood inside the imaging volume at 1.5 T. Recently, velocity-selective saturation (VSS) pulse trains were applied to suppress the static tissue and have been combined with SSI pulses for cerebral MR arteriography at 3 T. The aim of this study is to construct an abdominal MRA protocol with large spatial coverage at 3 T using advanced velocity-selective pulse trains.

Methods

Multiple velocity-selective MRA protocols with different sequence modules and 3D acquisition methods were evaluated. Sequences using VSS only as well as SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS preparations were then compared among a group of healthy young and middle-aged volunteers. Using MRA without any preparations as reference, relative signal ratios and relative contrast ratios of different vascular segments were quantitatively analyzed.

Results

Both SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriograms achieved high artery-to-tissue and artery-to-vein relative contrast ratios above aortic bifurcation. The SSI+VSS sequence yielded lower signal at the bilateral iliac arteries than VSI+VSS, reflecting the benefit of the VSI preparation for imaging the distal branches.

Conclusion

The feasibility of noncontrast 3D MR abdominal arteriography was demonstrated on healthy volunteers using a combination of VSS pulse trains and SSI or VSI pulse.

Keywords: abdominal MRA, arteriography, non-contrast-enhanced MRA, velocity-selective pulse train

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Abdominal MRA, as an ionizing radiation-free imaging modality, plays a significant clinical role in the setting of aortoiliac and visceral vascular pathology, including steno-occlusion, aneurysm, and dissection.1 It provides both contrast-enhanced and non-contrast-enhanced (NCE) approaches.2

Allowing large spatial coverage and rapid acquisition, gadolinium-based contrast-enhanced MRA has been established for examining abdominal aorta and its major branches for various applications.3–5 However, the use of traditional gadolinium-based contrast agents is restricted for patients with severe renal impairment, due to the risk of developing life-threatening nephrogenic systemic fibrosis.6,7 There is also growing concern for gadolinium deposition within the body and deep brain even when no kidney disease is present.8 This is particularly significant for patients with vascular pathology, as they often undergo serial surveillance exams, resulting in larger cumulative doses of gadolinium contrast.9 Although the clinical implications of gadolinium deposition remain largely unknown, current Food and Drug Administration guidelines recommend that health care professionals “minimize repeated GBCA imaging studies when possible, particularly closely spaced MRI studies.”10 Given these concerns, alternative blood-pool contrast agents such as ferumoxytol have been used for cardiovascular MRI.11,12 Nonetheless, other disadvantages of contrast-enhanced MRA persist, including the need for intravenous injection and potential anaphylactic reaction to contrast materials,13 as well as the additional cost.

Non-contrast-enhanced MRA does not require exogenous contrast agents, and therefore is ideal for first-line screening or frequent monitoring in follow-up exams, especially for patients with renal impairment.14 Several NCE-MRA techniques have been applied for depicting vasculatures of the abdomen.15 Three-dimensional half-Fourier fast spin-echo acquisition with electrocardiographic (ECG) gating provides arteriography by subtracting two images acquired at systolic and diastolic phases based on the dephasing of fast arterial flow during systole.16,17 Three-dimensional balanced SSFP (bSSFP) acquisition has been combined with ECG triggering and respiratory gating, with and without aortic labeling pulses, to image renal arteries through subtraction.18

Because bSSFP offers high blood signal due to both its intrinsic T2/T1 contrast and its inherent flow compensation in all three spatial coordinates,19 it is a popular choice for NCE-MRA,14,15,20 especially at low field. Renal arteriography with bSSFP under breath-holding has been demonstrated by applying three spatially selective saturation pulses before the acquisition module for venous suppression: one slab covering each kidney for saturating signal from renal veins, and the third one positioned below the two kidneys for mitigating signal from inferior vena cava.21–24 This method was applied to detect renal artery stenosis at the main renal arteries before branching to segmental and intrarenal arteries. However, its maximum-intensity projection (MIP) images often have insufficient quality, as the blood signal gets overlapped with hyperintensity of fluid and fat in the surrounding tissue with high T2/T1 ratios also.21 Nevertheless, this technique does not need paired acquisitions for subtraction, thus reducing both the time required and the sensitivity to motion- induced misregistration.

To suppress both the renal parenchyma and veins, non-subtraction-based ECG-triggered and respiratory-gated 3D bSSFP sequence for renal arteriography was further developed using an SSI pulse followed by a delay, during which fresh upstream arterial blood above the inversion volume flows into the imaging slab.25 Variants of this technique were applied for depicting renal arteries,26–28 hepatic arteries,29 hepatic veins,30 and portal veins,31 with the respiratory triggering. For this method, better visibility of distal arterial blood with longer inflow time is restricted by the suboptimal background suppression due to partial recovery of the static tissue signal. Thus, in practice, an inflow time of 0.8–1.4 seconds was often used for a 100–120 mm slab coverage in the axial plane. To extend the superior–inferior FOV to the entire abdominal and pelvic arteries, a method performed coronal imaging and applied a sagittally prescribed SSI pulse immediately following a nonselective inversion pulse to reinvert the spins within the abdominal aorta above the aortic bifurcation.32 However, this demanded careful manual placement of the SSI pulse, which also adversely caused a bright background sagittal band.

Alternatively, a velocity-selective inversion (VSI) pulse triggered by respiratory bellows and ECG signals sequentially was proposed for imaging abdominopelvic arteries with 3D bSSFP in coronal orientation at 1.5 T.33 The VSI pulse was aimed to invert the stationary tissue and venous blood and null these signals at the end of the inversion delay, while preserving arterial blood in the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries within the FOV. The original scheme of the velocity-selective pulse train,34 which did not include any refocusing pulses in the velocity-encoding segments, is known to be sensitive to off-resonance-induced phase modulation.

The emerging velocity-selective (VS)-MRA method has also been developed for other parts of the body,35,37 in which velocity-selective saturation (VSS) pulse trains were applied right before the acquisition module to suppress the static tissue and the slow venous flow with properly designed saturation band and passband. The susceptibility to B0 field inhomogeneity was alleviated moderately, by incorporating a single refocusing pulse within each velocity-encoding step, to around ±80 Hz for peripheral MRA at 1.5 T.35 Through paired and phase-cycled refocusing pulses, the immunity to off-resonance was further improved to around ±200 Hz for cerebral MRA36 and peripheral MRA37 at 3 T. A combination of SSI pulse with a preset delay and a VSS pulse train has been successfully demonstrated for cerebral MRA at 3 T with superior background tissue suppression and good separation of intracranial arterial and venous blood.38

In this study, we aimed to construct NCE abdominal MRA protocols at 3 T with large spatial coverage and without special planning, which are ideally suited for clinical applications. Abdominal arteriography applying various acquisition modules with VSS pulse trains and SSI or VSI preparation pulses were compared with quantitative evaluations among a group of healthy young to middle-aged volunteers.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Pulse sequences

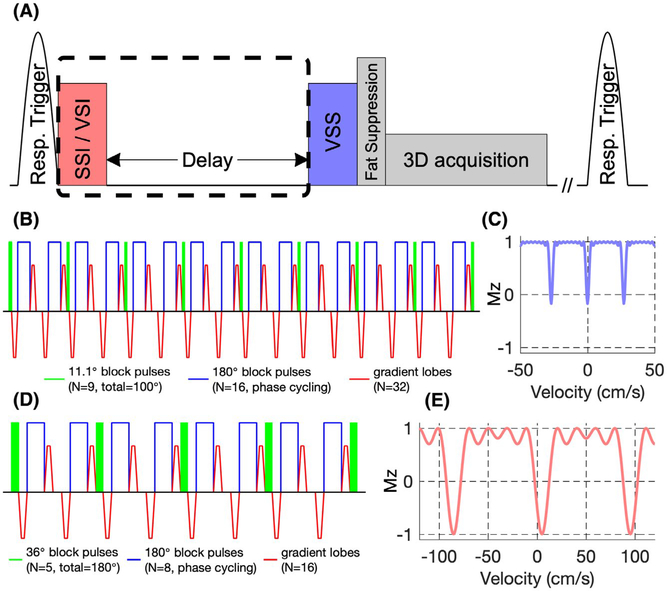

Variations of the VS-MRA protocols were performed with the pulse-sequence diagrams shown in Figure 1A. Velocity-selective MRA sequences were triggered by respiratory bellows to minimize motion artifacts.

FIGURE 1.

A, Diagram of the abdominal velocity-selective (VS)-MRA sequences. A Fourier transform–based velocity-selective saturation (VSS) pulse train was placed right before fat suppression and 3D acquisition modules to suppress static tissue. Spatially selective inversion (SSI) or velocity-selective inversion (VSI) pulse with an inversion delay (dashed box) was applied to null venous blood signal for arteriography. Respiratory triggering was used before preparations. Diagram of the VSS pulse train (B) and its corresponding VS profile (C). Note that the longitudinal magnetization (Mz) for tissue (v = 0 cm/s) should be close to 0 when taking into account the T2 effect. Diagram of the VSI pulse train (D) and its corresponding VS profile (E)

A Fourier transform–based VSS pulse train was placed right before fat suppression and 3D bSSFP acquisition modules to suppress static tissues. The VSS pulse train, as detailed in Qin et al,36 consists of nine excitation pulses (11.1° block pulses) with eight velocity-encoding steps (11 ms each) interleaved with paired and phase-cycled block-refocusing pulses and gradient lobes with alternating polarity (29.0 mT/m, 0.5-ms duration, 0.2-ms ramp time). This 88-ms VSS pulse train is illustrated in Figure 1B. The paired and phase-cycled (MLEV-16 scheme39) refocusing through the velocity-encoding steps enabled robustness within ±200 Hz B0 off-resonance and ±0.2 B+1 scales. Its velocity-selective profile (Figure 1C) was generated through numerical simulations of the Bloch equations using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). The targeted saturation band was within ±3.0 cm/s with periodical aliasing sidebands every 27 cm/s due to limited-velocity FOV. Velocity-encoding gradients were applied along 45° between left–right (LR) and foot–head (FH) directions. Note that the accumulation of nine 11.1° pulses yields an effective flip angle of 100° for static tissue, to compensate for the T2 relaxation during the VSS pulse train.

As described in Li et al,38 for obtaining arteriography, an adiabatic SSI pulse (HSn,40,41 n = 4, β = 4, 20 ms, bandwidth = 2500 Hz) was applied with an inversion delay to null the venous signal. During the inversion delay, fresh blood signal from the proximal aorta washes into the imaging volume and fills the major abdominal and iliac arteries, depending on the flowing velocity.

Alternatively, instead of the SSI pulse, a VSI pulse train was used to reduce the sensitivity to transit time in the large arteries.33 The VSI pulse train (Figure 1D) contains five excitation pulses (36° block pulses) with four velocity-encoding steps (11 ms each) and eight gradient lobes (8.8 mT/m, 0.5-ms duration, 0.2-ms ramp time). The inversion band was designed to be between −11.0 cm/s and 21.0 cm/s along the diagonal line in the coronal plane, where positive values were in the head and right directions. The purpose was to invert magnetization from large venous vessels and static tissue (contributing to small veins after delay) and not to perturb the spins of large arterial vessels (contributing to small or distal arteries after delay). Due to the periodic property of the VS profile, the inversion band repeated every 90 cm/s (Figure 1E).

2.2 |. Imaging protocol

Experiments were performed on a 3T scanner (Ingenia; Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) using the body coil for RF transmission (maximum B+1 amplitude = 13.5 μT) and a 32-channel chest-array coil for signal reception. The maximum strength of the gradient coil was 40 mT/m and the maximum slew rate was 200 mT/m/ms. A total of 14 healthy volunteers (age range: 24–60 years, 6 males and 8 females) were enrolled after providing informed consent in accordance with the institutional review board guidelines. Volunteer consent forms for publishing their images with their age and gender information were also obtained.

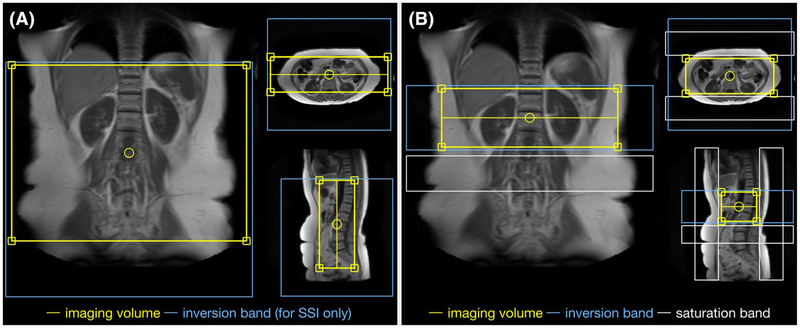

For each VS-MRA protocol, a spectral presaturation with inversion recovery module was applied right before the acquisition train for fat suppression. A 120-mm-thick coronal imaging slab with a FOV of 300 (FH) × 400 (LR) mm2 (Figure 2A, the yellow box) was acquired with LR as the phase-encoding direction and a resolution of 1.4 (FH) × 1.4 (LR) × 2.0 (anterior–posterior [AP]) mm3, and was reconstructed to 0.78 (FH) × 0.78 (LR) × 1.00 (AP) mm3 through zero padding. The SSI pulse covered the imaging volume with 100-mm extension in the foot direction (Figure 2A, blue box) to mitigate contamination of venous signal stemmed from within the imaging volume as well as inflowing from the inferior vena cava (IVC). Multishot 3D bSSFP acquisition module was used with radial low-high profile ordering.42 The bSSFP acquisition started with an α/2 excitation pulse with a TR/2 period to quickly stabilize the signal on the transient phase after magnetization preparation,43 and was followed by alternating ±α excitation pulses separated by TR. The parameters were TR/TE = 4.7/2.2 ms, flip angle α = 80°, and readout bandwidth = 1330 Hz/pixel. 70 k-lines were acquired for each shot with an acquisition window of 330 ms. Compressed-sensing technique44–46 was adopted with an acceleration factor of 8. A minimal shot interval was set as 3.5 seconds, and a total scan duration was about 3–4 minutes, depending on the individual breathing cycle.

FIGURE 2.

Positioning of the MRA sequences used in this study. The yellow boxes indicate the imaging volumes for the different abdominal VS-MRA protocols with VSS, SSI+VSS, or VSI+VSS preparations, all with a 300-mm spatial coverage in the foot–head (FH) direction (A), and the vendor-provided SSI-based renal MRA protocol (B-TRANCE), with a 100-mm coverage in the FH direction (B). The blue boxes indicate the inversion bands applied in the SSI-VSS-prepared abdominal MRA scans (A) and the SSI-prepared renal MRA scans (B), both with default inversion delays of 1200 ms. The white boxes in (B) indicate the saturation bands applied for venous or fat suppression right before the acquisition

Velocity-selective MRA with different sequence modules and acquisition methods was first evaluated among 3 volunteers (1 male, 45 years old; 2 females, 25 and 54 years old). To inspect the effect of tissue suppression at 3 T using the combination of inversion and VSS together, we performed scans with SSI+VSS, VSI+VSS, SSI only,25 and VSI only33 arteriography. To compare with bSSFP, turbo field-echo (TFE) acquisition, which has been used previously for cerebral MRA at 3 T,38 was also tested in this abdominal MRA study. With matched FOV and resolution, the parameters for TFE were TR/TE = 10.0/2.6 ms, flip angle α = 10°, readout bandwidth = 266 Hz/pixel, and TFE factor = 70 k-lines. The second-order B0 shim (Pencil-Beam method), along with the patient-adaptive RF shim using two parallel transmission channels, both provided by the vendor, were applied to mitigate the effect of the inhomogeneous B0/B1 field of the large abdomen volume at 3 T.

Velocity-selective MRA with VSS pulse train only, as well as with additional SSI or VSI preparations, was obtained from 9 healthy volunteers (45 ± 15 years old, 4 females) for comparison. These scans were all acquired with bSSFP acquisition. The default inversion delay times were 1200 ms for SSI and 700 ms for VSI preparations, as used in Shin et al.33 In a subgroup of 8 subjects, the data were acquired with delay times of 1100, 1200, and 1300 ms for SSI+VSS arteriography, and 600, 700, and 800 ms for VSI+VSS arteriography, respectively, to evaluate the inversion delays following the SSI and VSI modules. Given that the T1 of in vivo venous blood at 3 T is about 1.8 seconds,47,48 the nulling time of venous blood should be approximately 1250 ms with perfect inversion and a shot interval of 3.5 seconds. Respirational triggering would cause shot intervals to vary, depending on the breathing cycle. The nulling time after VSI pulse would be shorter, considering that the inversion degree of the VSI pulse train was sensitive to B1 inhomogeneity.38,49 Among a subgroup of 7 subjects, a reference scan without applying any of the VSS, SSI, or VSI preparation pulses was also acquired with the same acquisition parameters, to compare the signal of arteries, veins, and the static tissue.

A conventional respiratory-triggered SSI-based renal MRA protocol (B-TRANCE; Philips Medical Systems) was also acquired for these 9 subjects, for comparison. The imaging volume was placed in axial plane with FOV = 300 (LR) × 120 (AP) × 100 (FH) mm3 (Figure 2B, yellow box), AP as phase-encoding direction, resolution = 1.5 (LR) × 1.5 (AP) × 2.0 (FH) mm3, and was reconstructed to 0.75 (FH) × 0.75 (LR) × 1.00 (AP) mm3. The SSI pulse inverted the 100-mm imaging slab with an inversion delay of 1200 ms (Figure 2B, blue box). Before acquisition, three saturation pulses were applied with one 80-mm-thick axial slab below the imaging volume, to reduce the downstream signal of IVC, and two coronal slabs with 60-mm thickness or more to suppress anterior and posterior subcutaneous fat, respectively (Figure 2B, three white boxes). A pair of 1–3-3–1 fat-suppression binomial pulses (ProSet; Philips Medical Systems) were applied for water-only acquisition. Multishot 3D bSSFP acquisition module was in linear profile ordering. The acquisition parameters were TR/TE = 6.7/3.4 ms, flip angle α = 27°, readout bandwidth = 1330 Hz/pixel, TFE factor = 73 k-lines (with 9 dummy echo included), and SENSE acceleration factor = 2.2. A minimal shot interval was set as 1.4 seconds, and total scan duration was about 6 minutes.

Finally, a 2D phase-contrast velocity mapping (QFlow; Philips Medical Systems) was acquired for each subject to measure aortic and IVC flow velocities at 20 phases through a cardiac cycle. Q-flow was obtained within one breath-hold, and cardiac beats were triggered by a peripheral pulse unit. A slice with 8-mm thickness was placed axially and about 5 mm distally to the lower renal branch of the aorta with FOV = 350 (LR) × 300 (AP) mm2 and resolution = 2.0 (LR) × 2.0 (AP) mm2.

2.3 |. Quantitative assessment

Experimental data were analyzed using MATLAB. Twelve circular regions of interest (ROIs) were manually drawn on the coronal MIP images at the hepatic level, renal level, aortic bifurcation and iliac bifurcation, including four ROIs on the descending abdominal aorta and iliac arteries, four on the IVC and iliac veins, and the remaining four on background static tissue at each level.

Relative signal ratios between signal intensities of MRA images with VSS, SSI+VSS, and VSI+VSS preparation pulses and the corresponding reference scans without using any preparation pulses were quantified for each ROI. Relative contrast ratios between signal intensities of artery blood and static tissue were calculated as (arterial signal – static tissue signal)/arterial signal on VSS full angiogram, SSI+VSS, and VSI+VSS arteriograms, respectively. Relative contrast ratios between signal intensities of arterial and venous blood were also computed as (arterial signal – venous signal)/arterial signal for SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriograms.

3 |. RESULTS

Figure 3 shows the arteriograms of a 25-year-old female with different sequence modules using SSI (top row) and VSI (bottom row) preparations. When not applying the VSS pulse trains right before the acquisitions, residual background tissue from imperfect nulling obscured the vessel signal in the coronal MIP for the sequences using SSI or VSI alone (left column). The combination of inversion and VSS pulses revealed arterial structures with much improved tissue suppression (middle column). Replacing bSSFP acquisitions with TFE yielded lower arterial signal (right column). In this example, compared with the SSI-based arteriograms (top row), the VSI-based ones (bottom row) depicted more signal in proximal aorta, distal iliac arteries, and their small branches.

FIGURE 3.

Coronal maximum intensity projection (MIP) arteriography from a 25-year-old female using SSI (top row) and VSI (bottom row) preparations. Comparisons were made among sequences applying SSI or VSI only with balanced SSFP (bSSFP) acquisition (left column), a combination of SSI or VSI with VSS using bSSFP (middle column), and turbo field-echo (TFE) (right column) acquisitions, respectively

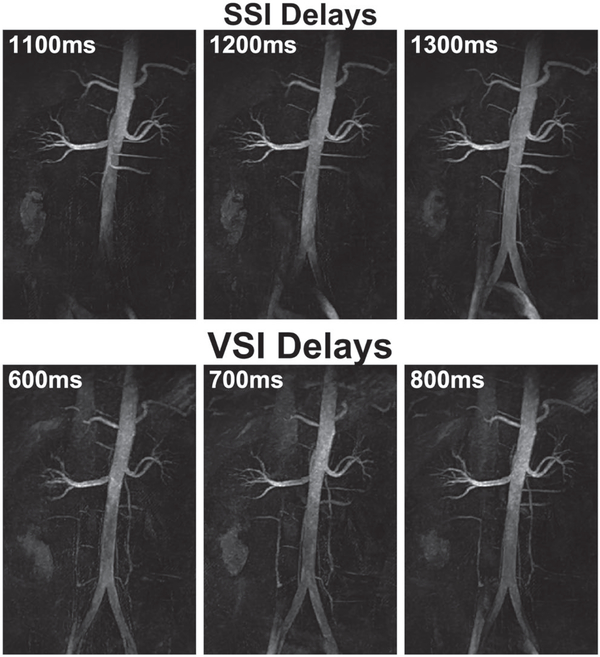

Results of a 24-year-old male using SSI+VSS with 1100, 1200, and 1300 ms delay times (top row) and VSI+VSS with 600, 700, and 800 ms delay times (bottom row) are displayed in Figure 4. Because SSI+VSS arteriography is totally inflow-based, longer delay times led to better depiction of distal iliac arteries and small arterial branches. For VSI+VSS, the signal in distal branches was much less dependent on the delay times. Both methods displayed increasing contamination from iliac veins and IVC with longer delays, most likely due to the inflow of upstream venous spins that were inadequately inverted by SSI or VSI pulses. The adiabatic SSI pulse produced more uniform background tissue suppression than the VSI pulse train. Tissue recovery with the longer delay times was not apparent because of applying the VSS pulse train right before the data acquisition.

FIGURE 4.

Coronal MIP arteriography from a 24-year-old male using SSI+VSS (top row) and VSI+VSS (bottom row) preparations with various inversion delays

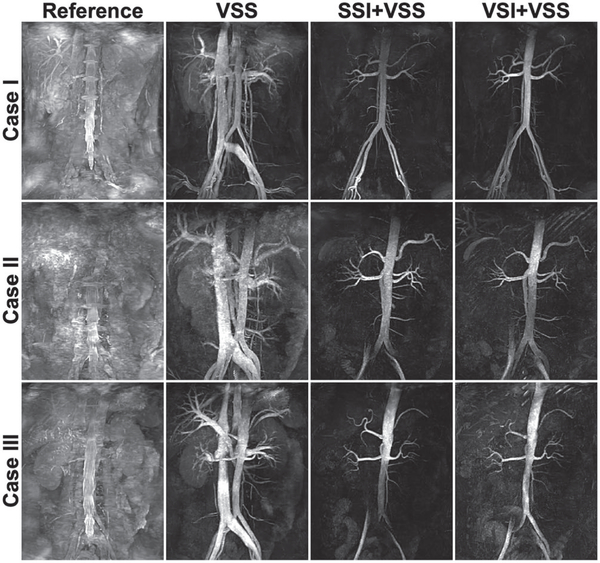

Figure 5 exhibits the coronal MIPs of the reference scans (first column), VSS-based angiograms (second column), and SSI/VSI+VSS-based arteriograms (third/fourth columns) of three cases: (1) a 25-year-old female (top row), (2) a 33-year-old male (middle row), and (3) a 55-year-old female (bottom row). One representative axial slice of the corresponding source images of each of the three cases is displayed in Supporting Information Figure S1. For all three cases, the VSS-only sequences greatly enhanced blood contrast with visualization of the major abdominal vasculature, including the descending aorta and distal iliac arteries, ascending IVC, portal venous system, hepatic, renal and splenic vessels, and many small, secondary branches. The SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS scans largely nulled venous signal except some residuals in iliac veins, with visualization of the aorta and its major branches, including the celiac trunk, common hepatic and splenic arteries, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, renal arteries, and the more diminutive spinal arteries. The VSI-based method produced better signal than SSI in the distal iliac arteries of cases 2 and 3, as the inflow-based SSI approach is susceptible to the slower refreshing of downstream arterial blood of middle-aged subjects.

FIGURE 5.

Coronal MIP images of the reference scans without applying any of the VSS, SSI, or VSI preparation pulses (first column), full angiograms of both arteries and veins using the VSS pulse train for static tissue suppression (second column), and arteriograms using the SSI+VSS sequence (third column) and VSI+VSS sequence (fourth column), from a 25-year-old female (case 1, top row), a 33-year-old male (case 2, middle row), and a 55-year-old healthy female (case 3, bottom row), respectively

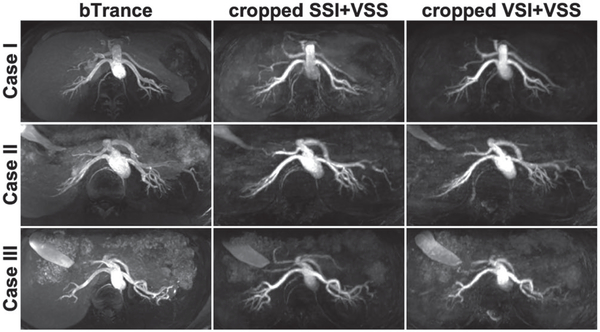

For the same three cases, Figure 6 displayed their axial MIP images of SSI-based renal MRA (B-TRANCE, left column) and the SSI/VSI+VSS-based MRA cropped from the renal portion (middle/right columns) with the matched spatial coverage in the FH dimension (100 mm). Detailed renal artery branches were visualized in all three methods, with better tissue suppression achieved using the VS-MRA approaches.

FIGURE 6.

Axial MIP images from cases 1, 2 and 3, showing renal arteriograms using B-TRANCE (left column), SSI+VSS (middle column), and VSI+VSS (right column), respectively. The VS-MRA results were cropped from 300 mm to 100 mm in the FH direction to match the spatial coverage of B-TRANCE. Comparing to B-TRANCE, our VS-MRA methods delineated detailed renal artery branches with better tissue suppression, while achieving 3 times the spatial coverage (300 mm vs. 100 mm) in almost half of the acquisition time (3–4 minutes vs. 6 minutes)

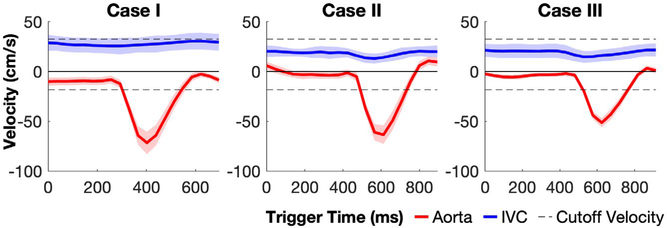

The averaged blood velocities of the aorta and IVC lumen through different cardiac phases of an R-R interval measured from these three cases are shown in Figure 7. The descending aorta blood reached the peak velocities at the systole (case 1: −75 ± 4 cm/s; case 2: −65 ± 4 cm/s; case 3: −55 ± 4 cm/s.), but maintained at low velocities (below 10 cm/s) during diastole. The ascending IVC remained at relatively constant velocities (case 1: 27 ± 4 cm/s; case 2: 24 ± 4 cm/s; case 3: 20 ± 4 cm/s) without much pulsation effects. The inversion band for the applied VSI pulse train ([−15.7, 30.0] cm/s along the FH direction, dashed lines) falls mostly between the velocities of aorta and IVC.

FIGURE 7.

Averaged blood velocities of the descending aorta (red) and ascending inferior vena cava (IVC; blue) lumen through different cardiac phases during an R-R interval measured from cases 1, 2, and 3. The inversion band for the applied VSI pulse train ([−15.7, 30.0] cm/s along the FH direction) is indicated as the range between the dashed lines

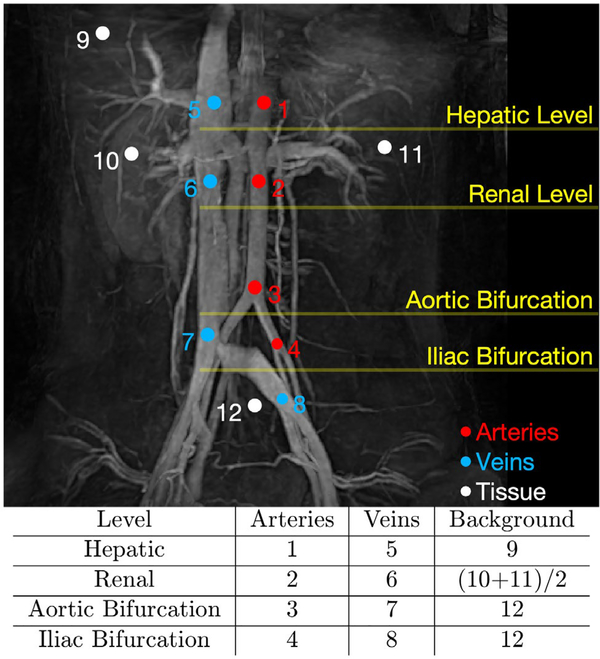

The ROIs of arteries (1, 2, 3, and 4), veins (5, 6, 7, and 8) and tissues (9, 10, 11, and 12), placed at hepatic level, renal level, aortic and iliac bifurcations, are exhibited on a coronal MIP image of the VSS-prepared MRA (Figure 8). The diameters of all circular ROIs were 7.8 mm, except the ones on iliac arteries (4) and veins (8), which were 6.3 mm due to the smaller size of iliac vessels. The tissue ROI 9 for the hepatic level was drawn at the right liver lobe, avoiding the portal veins. Left and right kidney ROIs (10 and 11) were averaged for the tissue at the renal level. Region of interest 12 represented the tissue at both levels of aortic and iliac bifurcations.

FIGURE 8.

Regions of interest (ROIs) drawn for the quantitative assessment of both relative signal ratios and relative contrast ratios in major abdominal vascular segments are schematically shown on a coronal MIP image obtained using the VSS-prepared full angiogram

The measured relative signal ratios of different ROIs between the scans with VSS, SSI+VSS, and VSI+VSS preparations and without any preparations (the reference scans) averaged across seven subjects are listed in Table 1. When VSS pulse trains were applied, 49%−55% of signal intensity in different segments of descending aorta and iliac arteries and 60%−68% of signal in ascending IVC and iliac veins was preserved. About 16%−30% of signal at static tissue background were left. Note that the signal intensity at the right kidney tissue was higher than the left side (0.30 ± 0.08 vs. 0.23 ± 0.08). When SSI or VSI pulse trains were applied, only 11%−13% (SSI) or 12%−16% (VSI) of signal in major veins and 8%−11% of signal in static tissue were left; preserved arterial signal from proximal to distal levels was reduced from 38% to 15% (SSI) or from 38% to 22% (VSI), following a decreasing pattern (Table 1).

Table 1.

Averaged relative signal ratios from different ROIs for different VS-MRA protocols

| Tissue | Location | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteries | Hepatic Level | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.38 ± 0.17 | 0.38 ± 0.12 |

| Renal Level | 0.55 ± 0.12 | 0.37 ± 0.14 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | |

| Aortic Bifurcation | 0.55 ± 0.18 | 0.27 ± 0.12 | 0.31 ± 0.17 | |

| Iliac Bifurcation | 0.53 ± 0.13 | 0.15 ± 0.11 | 0.22 ± 0.10 | |

| Veins | Hepatic Level | 0.60 ± 0.18 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.05 |

| Renal Level | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | |

| Aortic Bifurcation | 0.68 ± 0.16 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | |

| Iliac Bifurcation | 0.66 ± 0.19 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.05 | |

| Static Tissue | Liver | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.03 | 0.11 ± 0.03 |

| Right Kidney | 0.30 ± 0.08 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | |

| Left Kidney | 0.23 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | |

| Below Iliac Branch | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.03 | 0.10 ± 0.04 |

Note: The ROIs are labeled in arteries, veins, and static tissue at various locations, as shown in Figure 8. The reference scans were acquired without applying any preparation pulses.

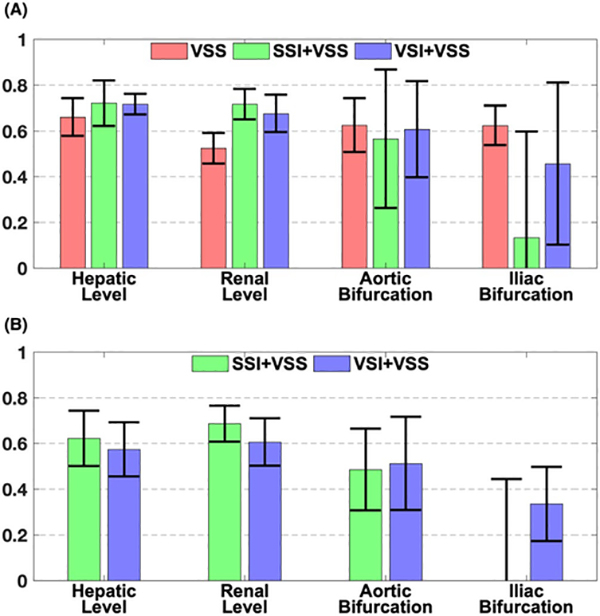

The averaged relative contrast ratios of artery-to-tissue and artery-to-vein at four different levels on VSS angiogram, SSI+VSS, and VSI+VSS arteriograms are shown in Figure 9A,B, respectively. For VSS angiography, the artery-to-tissue relative contrast ratios were mostly above 0.60 except at the renal level (0.52). For SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriography, these ratios increased to about 0.70 at the hepatic and renal levels due to the better tissue suppression (Figure 9A). The contrast ratios were slightly lower than VSS at the aortic bifurcation level. At the iliac bifurcation level, the artery-to-tissue relative contrast ratio of SSI+VSS was lower than 0.20, whereas the VSI+VSS approach was around 0.46, with an improvement of 130% (Figure 9A). Artery-to-vein relative contrast ratios follow the same decreasing pattern from proximal to distal levels (Figure 9B). For both SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS, artery-to-vein relative contrast ratios were about 0.60 at the hepatic and renal levels and about 0.50 at the aortic bifurcation level. At the iliac bifurcation level, this ratio of SSI+VSS was lower than zero, but VSI+VSS still yields a contrast of around 0.34 (Figure 9B).

FIGURE 9.

Averaged relative contrast ratios of artery-to-tissue at different vascular locations on VSS angiogram, SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriograms (A), and artery-to-vein on SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriograms, respectively (B)

4 |. DISCUSSION

The feasibility of 3D abdominal VS-MRA at 3 T with a large FOV was evaluated among a group of healthy young and middle-aged volunteers. The protocols under investigation used advanced VSS pulse trains immediately before image acquisition for suppression of static tissue. The SSI or VSI module with an inversion delay time was placed to null the venous signal for arteriography.

Both SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriography achieved high artery-to-tissue and artery-to-vein relative contrast at levels from liver to aortic bifurcation (Figure 9). The SSI-prepared method is inflow-based; thus, the extent of the arterial segments being displayed, such as the bilateral iliac arteries, could be hampered by the slow velocity of arterial blood in some subjects (Figures 4 and 5). In contrast, the arterial signal in distal branches was less dependent on the arterial inflowing speed for the VSI-based approach, as reflected in both representative cases (Figures 4 and 5) and the quantitative evaluation of the artery-to-tissue relative contrast ratios within the group (Figure 9). Velocities of aorta with normal cardiovascular functions were reported to be correlated with, for example, heart rate, age, gender, and body size.50 Older subjects tend to have slower flow velocity (Figure 7) and thus might benefit more from the VSI-based method.

When compared with reference scans, applying only VSS pulse trains was found to reduce the signal in half of the segments of the descending aorta and iliac arteries (Table 1). Signal drop was attributed primarily to T2 relaxation and pulsation during the 88-ms VSS pulse train.36 To alleviate the signal loss in the arterial blood, shortening the pulse duration with better performance of gradient is required.

The velocity-selective gradients were applied along a 45° angle in both the LR and FH directions, as the aorta, IVC, iliac arteries, and veins are largely in the FH direction, and the common hepatic artery, splenic artery and vein, renal arteries, and veins are primarily in the LR direction. All of these vessels have velocity components projected on the velocity-encoded direction. In addition, the portal system, which primarily supplies the liver, is approximately parallel to the chosen direction. A notable limitation of this implementation is that vessels flowing in the AP direction, such as the celiac trunk, might be poorly delineated. This could be avoided by choosing a velocity-selective direction slightly off the coronal plane and will be evaluated in future work. The saturation band for the VSS pulse train, [−3.0, 3.0] cm/s, and the inversion band for VSI, [−11.0, 21.0] cm/s, along the diagonal direction were projected to be [−4.3, 4.3] cm/s and [−15.7, 30.0] cm/s along the LR and FH directions, respectively.

Note that velocities of the aorta during diastole recorded in representative cases were within the inversion band of VSI (Figure 7). This might explain the lower signal in the aortic lumen and some distal arterial branches compared with SSI-based results as observed in cases 2 and 3 (Figure 5). Electrocardiographic triggering of VSI at the systolic phase would avoid inverting the fast-moving arterial magnetization, as done in Shin et al.33 However, the ECG signal may be unreliable due to improper contact between the skin and electrodes or magnetohydrodynamic interference.

One challenge of the VSI pulse train used in this study is that its inversion degree was sensitive to B+1 scales, due to the use of hard pulses of low flip angles played at the beginning of each velocity-encoding step for weighting of the excitation k-space. In contrast, SSI-based arteriography using an adiabatic inversion pulse ensured robust suppression of static tissue and venous signal (Figures 4 and 5). The relatively inhomogeneous background suppression and the shorter delay times for the VSI-based method (700 ms vs. 1200 ms) were both the result of the inadequate inversion caused by this B1 dependence. Note that the severity of B1 field inhomogeneity within the abdomen at 3 T is associated with both body geometry and tissue composition.51,52 Larger body size with less fat fraction might induce more severe B+1 inhomogeneity due to the proximity between the high dielectric constant and the RF wavelength in water-containing tissue.51,52 In a recent cerebral VS-MRA study, nine 10° optimal composite pulses for the VSS pulse train were designed to achieve uniform suppression of stationary tissue.38 For the VSI pulse train used in this study, five 36° optimal composite pulses could be applied for robust inversion, by tailoring to the B+1 inhomogeneities in the abdomen at 3 T.

Another technical issue is that the blood within the heart should not be inverted by SSI or VSI pulses, as the affected blood flowing into the proximal abdominal aorta could display low signal (Figure 5). For SSI, when carefully choosing the inversion slab to avoid overlapping with the heart apex, the venous blood from the cranial part of the liver, which is often in the same axial plane of the base of the heart, may not be adequately suppressed. For VSI, the contraction of the myocardium may fall into the inversion band of the velocity-selective yet spatially nonselective pulse train and result in unintended perturbation.

Results in Figure 4 indicated better SNR of bSSFP over TFE acquisition for our VS-MRA methods at 3 T. Similar to previous implementations for cerebral or peripheral MRA,37,38,53 the bSSFP readout in this work used low-high profile ordering to acquire the center of k-space right after the VSS pulse train. This was to capture the maximal contrast between the flowing signal in the passband and the static tissue signal in the saturation band. Note that the signal evolution of the bSSFP readout follows an exponential decay or recovery, depending on the initial magnetization, from the first excitation pulse toward the stead state, and is characterized as the transient phase.43,54 Rather different from the well-known T2/T1 contrast expected at the steady state,19 the contrast of bSSFP readout during the transient state is governed by the contrast prepared before the acquisition module in addition to the imaging sequence parameters as well as the T1, T2 values of the tissues.43,54

A disadvantage of bSSFP is that it can be poorly affected by B0 field inhomogeneity,19 especially near the lung–liver interface. In this study, using second-order B0 shim and patient-adaptive B1 shim robustly achieved high-quality bSSFP-based abdominal MRA on our 3T system. The B0 shimming volume applied was the same as the imaging volume in the AP and FH directions, but only wide enough to cover both kidneys in the LR direction.

It is worth mentioning that the compressed-sensing technique was well-suited for VS-MRA due to its sparsity nature, and the acceleration factor of 8 enabled the acquisition duration for the large FH FOV (300 mm) within a time window of 3–4 minutes. In contrast, the SSI-based B-TRANCE renal MRA with only one third of the spatial coverage in the FH direction (100 mm) only applied the SENSE factor of 2.2 in the AP direction and took almost twice the acquisition time (6 minutes).

Respirational triggering at the exhale state ensured insensitivity to respiratory movement as well as variations of the B0 or B1 field inhomogeneities, but at the cost of lengthened acquisition time that are related to the breathing cycle. Advanced imaging and reconstruction methods, such as using radial or spiral trajectories, could potentially allow continuous acquisition during free breathing and thus further improve the imaging efficiency.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

Three-dimensional NCE abdominal MRA sequences using a combination of VSS pulse trains and SSI or VSI pulses were demonstrated for large spatial coverage at 3 T. Both SSI+VSS and VSI+VSS arteriography delineated the arterial segments above the aortic bifurcation. Compared with the SSI-prepared method, the VSI-based approach was less sensitive to slow arterial inflow and demonstrated better performance on bilateral iliac arteries. The clinical impact of these techniques needs to be evaluated among a large group of patients with various abdominal vascular disorders.

Supplementary Material

FIGURE S1 One representative axial slice from the source images of the three cases of Figure 5, displaying the reference scans (first column), full angiograms using the VSS pulse train for static tissue suppression (second column), and arteriograms using the SSI+VSS sequence (third column) and VSI+VSS sequence (fourth column), respectively

Acknowledgments

Funding information

National Institutes of Health; Grant/Award Numbers R01 HL138182 (Q.Q.) and NIH R01 HL135500 (T.S.)

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Laissy JP, Trillaud H, Douek P. MR angiography: noninvasive vascular imaging of the abdomen. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:488–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartung MP, Grist TM, François CJ. Magnetic resonance angiography: current status and future directions. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2011;13:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prince MR. Gadolinium-enhanced MR aortography. Radiology. 1994;191:155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prince MR, Narasimham DL, Stanley JC, et al. Breath-hold gadolinium-enhanced MR angiography of the abdominal aorta and its major branches. Radiology. 1995;197:785–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hany TF, Debatin JF, Leung DA, Pfammatter T. Evaluation of the aortoiliac and renal arteries: comparison of breath-hold, contrast-enhanced, three-dimensional MR angiography with conventional catheter angiography. Radiology. 1997;204:357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuo PH, Kanal E, Abu-Alfa AK, Cowper SE. Gadolinium-based MR contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis. Radiology. 2007;242:647–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadowski EA, Bennett LK, Chan MR, et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: risk factors and incidence estimation. Radiology. 2007;243:148–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald RJ, McDonald JS, Kallmes DF, et al. Intracranial gadolinium deposition after contrast-enhanced MR imaging. Radiology. 2015;275:772–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gulani V, Calamante F, Shellock FG, Kanal E, Reeder SB; ISMRM. Gadolinium deposition in the brain: summary of evidence and recommendations. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns that gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) are retained in the body; requires new class warnings. https ://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-andavailability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-warns-gadolinium-based-contrast-agents-gbcas-are-retai ned-body . Accessed May 16, 2018.

- 11.Hope MD, Hope TA, Zhu C, et al. Vascular imaging with ferumoxytol as a contrast agent. Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:W366–W373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finn JP, Nguyen K- L, Han F, et al. Cardiovascular MRI with ferumoxytol. Clin Radiol. 2016;71:796–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granata V, Cascella M, Fusco R, et al. Immediate adverse reactions to gadolinium-based MR contrast media: a retrospective analysis on 10,608 examinations. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:3918292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyazaki M, Lee VS. Nonenhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2008;248:20–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki M, Isoda H. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography of the abdomen. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:9–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyazaki M, Sugiura S, Tateishi F, Wada H, Kassai Y, Abe H. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography using 3D ECGsynchronized half-Fourier fast spin echo. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2000;12:776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyazaki M, Takai H, Sugiura S, Wada H, Kuwahara R, Urata J. Peripheral MR angiography: separation of arteries from veins with flow-spoiled gradient pulses in electrocardiography-triggered three-dimensional half-Fourier fast spin-echo imaging. Radiology. 2003;227:890–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spuentrup E, Manning WJ, Börnert P, Kissinger KV, Botnar RM, Stuber M Renal arteries: navigator-gated balanced fast field-echo projection MR angiography with aortic spin labeling: initial experience. Radiology. 2002;225:589–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheffler K, Lehnhardt S. Principles and applications of balanced SSFP techniques. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2409–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyazaki M, Akahane M. Non-contrast enhanced MR angiography: established techniques. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coenegrachts KL, Hoogeveen RM, Vaninbroukx JA, et al. High-spatial-resolution 3D balanced turbo field-echo technique for MR angiography of the renal arteries: initial experience. Radiology. 2004;231:237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herborn CU, Watkins DM, Runge VM, Gendron JM, Montgomery ML, Naul LG. Renal arteries: comparison of steady-state free precession MR angiography and contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Radiology. 2006;239:263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maki JH, Wilson GJ, Eubank WB, Glickerman DJ, Millan JA, Hoogeveen RM. Navigator-gated MR angiography of the renal arteries: a potential screening tool for renal artery stenosis. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:W540–W546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maki JH, Wilson GJ, Eubank WB, Glickerman DJ, Pipavath S, Hoogeveen RM. Steady-state free precession MRA of the renal arteries: breath-hold and navigator-gated techniques vs. CE-MRA. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26:966–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katoh M, Buecker A, Stuber M, Gunther RW, Spuentrup E. Freebreathing renal MR angiography with steady-state free-precession (SSFP) and slab-selective spin inversion: initial results. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1272–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shonai T, Takahashi T, Ikeguchi H, Miyazaki M, Amano K, Yui M. Improved arterial visibility using short-tau inversion-recovery (STIR) fat suppression in non-contrast-enhanced time-spatial labeling inversion pulse (Time-SLIP) renal MR angiography (MRA). J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:1471–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pei Y, Shen H, Li J, et al. Evaluation of renal artery in hypertensive patients by unenhanced MR angiography using spatial labeling with multiple inversion pulses sequence and by CT angiography. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:1142–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pei Y, Li F, Shen H, et al. Optimal blood suppression inversion time based on breathing rates and heart rates to improve renal artery visibility in spatial labeling with multiple inversion pulses: a preliminary study. Korean J Radiol. 2016;17:69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimada K, Isoda H, Okada T, et al. Non-contrast-enhanced hepatic MR angiography with true steady-state free-precession and time spatial labeling inversion pulse: optimization of the technique and preliminary results. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada K, Isoda H, Okada T, et al. Non-contrast-enhanced MR angiography for selective visualization of the hepatic vein and inferior vena cava with true steady-state free-precession sequence and time-spatial labeling inversion pulses: preliminary results. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shimada K, Isoda H, Okada T, et al. Non-contrast-enhanced MR portography with time-spatial labeling inversion pulses: comparison of imaging with three-dimensional half-fourier fast spin-echo and true steady-state free-precession sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;29:1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Atanasova IP, Kim D, Lim RP, et al. Noncontrast MR angiography for comprehensive assessment of abdominopelvic arteries using quadruple inversion-recovery preconditioning and 3D balanced steady-state free precession imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;33:1430–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin T, Worters PW, Hu BS, Nishimura DG. Non-contrast-enhanced renal and abdominal MR angiography using velocity-selective inversion preparation. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69:1268–1275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Rochefort L, Maitre X, Bittoun J, Durand E. Velocity-selective RF pulses in MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin T, Hu BS, Nishimura DG. Off-resonance-robust velocity-selective magnetization preparation for non-contrast-enhanced peripheral MR angiography. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70:1229–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Qin Q, Shin T, Schär M, Guo H, Chen H, Qiao Y. Velocity-selective magnetization-prepared non-contrast-enhanced cerebral MR angiography at 3 Tesla: improved immunity to B0/B1 inhomogeneity. Magn Reson Med. 2016;75:1232–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shin T, Qin Q, Park JY, Crawford RS, Rajagopalan S. Identification and reduction of image artifacts in non-contrast-enhanced velocity-selective peripheral angiography at 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76: 466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li W, Xu F, Schär M, et al. Whole-brain arteriography and venography: using improved velocity-selective saturation pulse trains. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:2014–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levitt MH, Freeman R, Frenkiel T. Broadband heteronuclear decoupling. J Magn Reson. 1982;47:328–330. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tannüs A, Garwood M. Improved performance of frequency‐swept pulses using offset‐independent adiabaticity. J Magn Reson Series A. 1996;120:133–137. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang TL, van Zijl PC, Garwood M. Fast broadband inversion by adiabatic pulses. J Magn Reson. 1998;133:200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holsinger AE, Riederer SJ. The importance of phase-encoding order in ultra-short TR snapshot MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1990;16:481–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheffler K On the transient phase of balanced SSFP sequences. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:781–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: the application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:1182–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lustig M, Donoho D, Santos JM, Pauly JM. Compressed sensing MRI. IEEE Signal Process Mag. 2008;25:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang D, Liu B, Wang J, Ying L. Accelerating SENSE using compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:1574–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qin Q, Strouse JJ, van Zijl PC. Fast measurement of blood T(1) in the human jugular vein at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:1297–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li W, Liu P, Lu H, Strouse JJ, van Zijl PCM, Qin Q. Fast measurement of blood T1 in the human carotid artery at 3T: accuracy, precision, and reproducibility. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77:2296–2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qin Q, van Zijl PC. Velocity-selective-inversion prepared arterial spin labeling. Magn Reson Med. 2016;76:1136–1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia J, van der Palen RLF, Bollache E, et al. Distribution of blood flow velocity in the normal aorta: effect of age and gender. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2018;47:487–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernstein MA, Huston J, Ward HA. Imaging artifacts at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:735–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merkle EM, Dale BM. Abdominal MRI at 3.0 T: the basics revisited. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:1524–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin T, Qin Q. Characterization and suppression of stripe artifact in velocity-selective magnetization-prepared unenhanced MR angiography. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80:1997–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmitt P, Griswold MA, Gulani V, Haase A, Flentje M, Jakob PM. A simple geometrical description of the TrueFISP ideal transient and steady-state signal. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FIGURE S1 One representative axial slice from the source images of the three cases of Figure 5, displaying the reference scans (first column), full angiograms using the VSS pulse train for static tissue suppression (second column), and arteriograms using the SSI+VSS sequence (third column) and VSI+VSS sequence (fourth column), respectively