Abstract

Aim

Our goal was to compare conformal 3D (C3D) radiotherapy (RT), modulated intensity RT (IMRT), and volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT) planning techniques in treating pituitary adenomas.

Background

RT is important for managing pituitary adenomas. Treatment planning advances allow for higher radiation dosing with less risk of affecting organs at risk (OAR).

Materials and methods

We conducted a 5-year retrospective review of patients with pituitary adenoma treated with external beam radiation therapy (C3D with flattening filter, flattening filter-free [FFF], IMRT, and VMAT). We compared dose-volume histogram data. For OARs, we recorded D2%, maximum, and mean doses. For planning target volume (PTV), we registered V95%, V107%, D95%, D98%, D50%, D2%, minimum dose, conformity index (CI), and homogeneity index (HI).

Results

Fifty-eight patients with pituitary adenoma were included. Target-volume coverage was acceptable for all techniques. The HI values were 0.06, IMRT; 0.07, VMAT; 0.08, C3D; and 0.09, C3D FFF (p < 0.0001). VMAT and IMRT provided the best target volume conformity (CI, 0.64 and 0.74, respectively; p < 0.0001). VMAT yielded the lowest doses to the optic pathway, lens, and cochlea. The position of the neck in extreme flexion showed that it helps in planning mainly with VMAT by allowing only one arc to be used and achieving the desired conformity, decreasing the treatment time, while allowing greater protection to the organs of risk using C3D, C3DFFF.

Conclusions

Our results confirmed that EBRT in pituitary adenomas using IMRT, VMAT, C3D, C3FFF provide adequate coverage to the target. VMAT with a single arc or incomplete arc had a better compliance with desired dosimetric goals, such as target coverage and normal structures dose constraints, as well as shorter treatment time. Neck extreme flexion may have benefits in treatment planning for better preservation of organs at risk. C3D with extreme neck flexion is an appropriate treatment option when other treatment techniques are not available.

Keywords: Pituitary adenomas, Conformal radiotherapy, IMRT, VMAT

Abbreviations: C3D, conformal three-dimensional radiotherapy; CI, conformity index; CT, computed tomography; CTV, clinical target volume; DVH, dose-volume histogram; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; ESAPI, Eclipse Scripting Application Programming Interface; FF, flattening filter; FFF, flattening filter free; CFRT, conventional fractionated radiotherapy; GTV, gross tumor volume; HI, homogeneity index; IMRT, modulated intensity radiotherapy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OAR, organs at risk; PTV, planning target volume; RION, radiation-induced neuropathy; RT, radiotherapy; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy

1. Introduction

Pituitary adenomas are benign tumors that arise from the adenohypophysis. They are the second most frequent intracranial tumor after meningiomas and represent 16.2% of all primary intracranial neoplasms in adults.1,2 Therapies for pituitary adenomas include transphenoidal surgery, medical treatment, and/or external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Radiotherapy (RT) is crucial in the management of pituitary adenomas with incomplete resection, biochemical or radiographic recurrence or persistence, and those with high risk of recurrence despite surgical resection.2, 3, 4 In previous reports, RT achieved a 10-year local control of up to 90%.5 Less commonly, RT has also been used in medically inoperable patients or irresectable adenoma.2, 3, 4

Despite the efficacy of RT, the high risk of long-term radiation-induced pituitary deficit and risks of neurological deficit have limited its use in the past. More recently, advances in radiological imaging, software systems applied to treatment planning, and radiation dose delivery have led to more precise planning treatments. Radiation techniques have evolved from conformal three-dimensional RT (C3D) through modulated intensity RT (IMRT), volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS). Techniques such as C3D with flattening filter (FF) and flattening filter-free (FFF) are used in small fields to achieve high compliance and, on the other hand, allow us to reduce the treatment time.5 Currently, VMAT and modulated intensity RT (IMRT) are used to decrease higher radiation doses to the target and reduce doses to the surrounding healthy brain structures while maintaining effective therapeutic dose for the tumor, and reducing long-term toxicity.5,6

2. Objective

The primary objective of this review was to perform a dosimetric comparison of 3 planning techniques for EBRT (C3D, IMRT, and VMAT) in patients with pituitary adenomas with incomplete resection, with biochemical or radiographic recurrence or persistence and in inoperable patients.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study population

We conducted a retrospective review of 58 patients diagnosed with pituitary adenoma treated with EBRT at our institution between December 2013 and June 2018. We evaluated clinical, pathological, and biochemical data and treatment and follow-up characteristics. For magnetic resonance image (MRI) response Peer-review of all magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) available in our PACS (Carestream Vue PACS) before EBRT, 3–6 months after EBRT, and final follow-up were conducted by brain MRI radiologists. The formula used for residual volume calculation [transverse * anteroposterior * craniocaudal diameters * (π/6)] is suggested mainly for measurements of ellipsoid targets. Despite its limitations for measurement of residuals, it was used instead of accurate GTV volume in cubic centimeters since initial evaluation and further follow-up measurements were done with the radiology department system.

3.2. Simulation and volume delineation

Computed tomography (CT) simulation was done with a thermoplastic mask with the patient’s neck in neutral position or extreme flexion. Extreme flexion was achieved by directing the base of jaw toward the sternal manubrium using a neck support. This position helped to avoid healthy structures, such as the optic pathway, retina and brain tissue, through the beam path. CT planning with 1.25 mm slice thickness was previously acquired and co-registered with the MRI sequences of interest using rigid fusion in the Eclipse Treatment Planning System (Version 11; Varian Medical Systems, Inc., Palo Alto, CA). All treatment volumes and organs at risk (OAR) contouring were reviewed. The gross tumor volume (GTV) was defined using MRI and CT. The clinical target volume (CTV) for non-operated patients was generated by a 3-mm to 5-mm isotropic margin (planning target volume [PTV] was the same as CTV). For operated patients, the CTV included the GTV with or without the tumor bed, and it was then expanded symmetrically by 3–5 mm to create the PTV to account for setup errors.7,8 The following OARs were included: lenses, cochlea, eyeballs, optic nerves, chiasm, brainstem, and spinal cord.9,10

3.3. Treatment planning technique

Four treatment plans were created for each case: C3D with flattening filter and flattening filter-free (C3D FFF), VMAT, and IMRT. The plans were optimized with the different treatment techniques using the Varian Millenium 120-leaf multileaf collimators, with a spatial resolution of 0.5 cm in the isocenter for the central 20 cm and 1 cm in the outer region. In the first step of the planning process, the objective was to achieve at least 95% of the PTV receiving 100% of the prescribed dose (54 Gy in 27 fractions). Next, we needed to optimize OAR sparing without compromising PTV coverage. Therefore, the following dose constraints were used: for optic pathway (chiasm and optic nerves) and brainstem, maximum dose lower than 54 Gy; for lenses, Dmax <2 Gy; for cochlea, mean dose <30 Gy and Dmax <40 Gy; and, for spinal cord, Dmax <45 Gy.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

All conformal plans were created with the four-field technique positioned at 0°, 90°, 180° and 270°, using 10-MV photons and with collimator set to 0° for all plans. Using the same beam arrangement and field size, the C3D FFF was calculated with 10 MV FFF and a dose rate of 2400 MU/min.

For the IMRT technique, 5 fields were created with 6 MV FFF photons positioned to 0°, 72°, 144°, 216°, and 288° for patient’s CT with neck flexion; for those with neutral neck position, in CT the fields were arranged at 180°, 230°, 280°, 80°, and 130°. For both scenarios, the collimator was placed at 0°, 20°, 40°, 60°, and 80°. The maximum dose rate was set at 1400 MU/min.

All VMAT plans were created with a full arc for 6 MV FFF photons; this arc was planned in a clockwise direction and with the collimator at 30°. In patients simulated with extreme neck flexion, a single complete arc was sufficient to achieve compliance with desired dosimetric goals, such as target coverage and normal structures dose constraints. For patient’s CT with no neck flexion, a restriction of 315°–45° was placed and the arc was incomplete to sparing OAR. The maximum dose rate was set at 1400 MU/min. Final calculations were performed using the AAA algorithm in Eclipse Version 11.

3.4. Plan analysis

With a previously generated structure template that included treatment volumes (GTV, CTV, PTV) and OARs and using the Eclipse Scripting Application Programming Interface (ESAPI), our medical physicists have developed a script (c# code program) enabling easier, faster, and more precise dose-volume histogram (DVH) evaluation of each of the 4 plans of the 58 patients. This script enables automatic export of the analyzed information to a database (Table 1).

Table 1.

Median size of residual tissue and pituitary gland on MRI.

| Residual size on MRI |

Pituitary size on MRI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T (W) | AP (H) | CC (L) | Va | T (W) | AP (H) | CC (L) | Va | |

| MRI before RT | 11.6 (0−46.6) | 5 (0−3.7) | 8.16 (0−4.6) | 0.272 (0−37.43) | 16.0 (0−46.6) | 6.2 (0−37) | 10.7 (0−46) | 0.63 (0−37.43) |

| MRI 3−6 months after EBRT | 7.5 (0−30) | 3 (0−20) | 5 (0−28) | 0.0591 (0−8.356) | 13 (0−30) | 5 (0−50) | 9 (0−28) | 0.3391 (0−8.35) |

| Last MRI | 10.39 (0−30.7) | 4 (0−22) | 7.43 (0−28.4) | 0.1088 (0−7.64) | 13 (0−30.7) | 4.55 (0−22) | 8.78 (0−28.4) | 0.2707 (0−7.64) |

| P-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

All diameters are in millimeters.

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RT, radiotherapy; AP, anteroposterior diameter; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; T, transverse diameter; W, width; H, height; L, length; CC, craniocaudal diameter; V, volume.

Volume was calculated by multiplying T × AP × CC × (π/6), expressed in centimeters.

The plans analyses were based on DVH data reported and exported through ESAPI code. For OARs, we recorded D2%, maximum (Dmax), and mean (Dmean) dose. And for PTV we additionally registered V95% and V107% (represent the volume receiving 95% and 107% or more of the prescribe dose, respectively), D95%, D98%, D50% and D2% (represent the dose received by 95%, 98%, 50%, and 2% of the structure, respectively), and minimum dose (Dmin). We also calculated the conformity index (CI) and the homogeneity index (HI) for the PTV (Table 2) using the following formulas:

-

-

HI (formula 1): calculated as maximum dose divided by prescribed dose

-

-

HI (formula 2): calculated as (D2%–D98%)/prescribed dose

-

-

CI (formula 1): calculated as treatment volume divided by PTV volume (VPTV)

-

-

CI (formula 2): calculated as (V95% ∩ VPTV)2/(V95% * VPTV)

Table 2.

Median dose in cGy (range) to PTV for C3D, C3D FFF, IMRT, and VMAT plans.

| PTV | C3D | C3D FFF | IMRT | VMAT | Friedman | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximuma | 5784 (5602−5952) | 5842 (5633−6046) | 5725 (5613−5841) | 5835 (5765−5946) | <0.0001 | |

| Minimuma | 5145 (4312−5302) | 5134 (4575−5293) | 5111 (4282−5252) | 5033 (4420−5227) | <0.0001 | |

| Meana | 5612 (5502−5729) | 5633 (5512−5755) | 5556 (5513−5629) | 5565 (5456−5633) | <0.001 | |

| D95% | cGy | 5400 (5318−5494) | 5400 (5319−5488) | 5400 (5381−5430) | 5400 (5121−5429) | 0.958 |

| % | 100 (98.5−101.7) | 100 (98.5−101.6) | 100 (99.7−100.6) | 100 (94.8−100.5) | 0.985 | |

| D98% | cGy | 5340 (5213−5414) | 5338 (5203−5410) | 5346 (5302−5380) | 5341 (5038−5359) | <0.0001 |

| % | 98.9 (96.5−100.3) | 98.9 (96.4–100.2) | 99 (98.2−99.6) | 98.9 (93.3−99.2) | 0.001 | |

| D50% | cGy | 5633 (5507−5777) | 5653 (5517–5786) | 5576 (5519−5667) | 5577 (5492−5673) | <0.0001 |

| % | 104.3 (102−107) | 104.7 (102.2–107.1) | 103.3 (102.2−105) | 103.3 (101.7−105.1) | <0.0001 | |

| D2% | cGy | 5765 (5591−5963) | 5813 (5616–6012) | 5666 (5593–5747) | 5728 (5646–5863) | <0.0001 |

| % | 106.8 (103.5−109.9) | 107.6 (104−111.3) | 104.9 (103.6−106.4) | 106.1 (104.6–108.6) | <0.0001 | |

| V95% | 99.91 (99.46−100) | 100 (99.38−100) | 100 (99.5−100) | 99.98 (94.64−100) | 0.011 | |

| V107% | 0.27 (0−49.66) | 10.07 (0−51.81) | 0 (0−0.35) | 0.23 (0−14.56) | <0.0001 | |

| HI1 | 1.07 (1.04−1.10) | 1.08 (1.04−1.12) | 1.06 (1.04−1.08) | 1.08 (1.07−1.10) | <0.0001 | |

| HI2 | 0.08 (0.04−0.12) | 0.09 (0.05−0.13) | 0.06 (0.04−0.08) | 0.07 (0.05−0.14) | <0.0001 | |

| CI1 | 1.56 (1.13−2.15) | 1.52 (1.14−2.1) | 1.06 (0.95−1.34) | 1.01 (0.25−1.12) | <0.0001 | |

| CI2 | 0.41 (0.29−0.53) | 0.42 (0−0.56) | 0.64 (0−0.77) | 0.74 (0.59−0.82) | <0.0001 | |

D95%, D98%, D50% and D2%: dose received by 95%, 98%, 50% and 2% of PTV in cGy or percentage. V95% and V107%: volume of PTV receiving or within the 95% and 107% isodose.

HI1: homogeneity index calculated as maximum dose divided by prescribed dose.

HI2: homogeneity index calculated as (D2%–D98%)/prescribed dose.

CI1: conformity index calculated as treatment volume divided by PTV volume (VPTV).

CI2: conformity index calculated as (V95% ∩ VPTV)2/(V95% * VPTV).

Abbreviations: PTV, planning target volume; C3D, conformal 3D radiotherapy; C3D FFF, conformal 3D radiotherapy flattening filter-free; IMRT, modulated intensity radiotherapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; HI homogeneity index; CI, conformity index.

Median dose (range) in cGy.

The higher values of CI indicated better PTV conformity. The closer to 1 of HI with formula 1 and the lower values of HI with formula 2 indicate more homogeneous irradiation of PTV.15,16

3.5. Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test was used to test for normality. Non-parametric statistical tests were used since data from PTV coverage and constraints to OARs had no normal distribution. To compare the PTV coverage and dose to OARs within the 4 different modalities (C3D, C3D FFF, IMRT and VMAT), non-parametric Friedman rank test for paired samples were used. Statistically significant difference was considered with p-value less than the significance level (α = 0.05). To specifically identify which RT technique differ from which other, in each value measured and statistically significant after Friedman test, we further used pairwise comparisons using the Nemenyi multiple comparison test (Friedman post-hoc test using RStudio version 1.2.5033).

4. Results

4.1. Patient characteristics

A total of 58 patients with pituitary adenoma diagnosis were treated with conventional fractionated RT (CFRT): 41 women (70.7%), and 17 men (29.3%). The mean age at recurrence and the radiation therapy beginning was 46 years (range, 22–90 years). The majority (39 patients) had macroadenomas (67.2%), and 19 patients had microadenomas (32.8%). With regard to the endocrine status, 15 patients (25.9%) had nonfunctioning adenomas, and 43 patients (74.1%) had hormone-secreting functioning adenomas; 23 (39.7%) had corticotrophin/adrenocorticotropic hormone-secreting tumors, 15 (25.9%) had growth hormone-secreting tumors, and 8 (13.8%) had prolactin-secreting tumors.

Among all, 51 patients (87.9%) received adjuvant radiation after surgical resection (47 transsphenoidal surgery, 3 hypophysectomies, 1 right subfrontal approach) with a median number of surgeries of 1 (range, 1–3); 4 patients (6.9%) received medical treatment before definitive RT (1 bromocriptine and 3 cabergoline); and, in 3 patients (5.2%), surgery was not feasible for medical reasons, and they received definitive RT. In 24 patients (41.4%), RT was indicated for recurrence (as the most frequent cause, biochemical recurrence in 15 patients [25.8%]), and in 32 patients (55.2%) due to persistence (the most common cause being residual identified by imaging in 22 patients [37.9%]).

4.2. Radiation therapy

RT was mainly administered to treat pituitary adenoma if surgical and medical treatments failed to remove the tumor or normalize hormone secretion. All patients received CFRT with a median overall treatment time of 39 days (range, 32–68 days), it was delivered with 3D-CRT in 45 patients (77.6%), VMAT in 10 patients (17.2%) with a median number of 5 fields (range, 5–7) and IMRT in 3 patients (5.2%) with a median number of 1 arc (range, 1–3). Median PTV volume was 5.32 cm3 (range, 1.04–34.74 cm3), with 45 patients with volume ≤10 cm3.

All patients were treated with once-daily megavoltage RT, 5 fractions per week. The median total dose delivered by TrueBeam linear accelerator (Varian Medial Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was 54 Gy (range, 46–54 Gy) with a median daily dose of 2 Gy (1.8–2.16 Gy). Nearly equal doses were applied regardless of the functional type of adenoma. With a median number of 27 sessions (range, 23–30), 1 patient received 46 Gy and suspended the treatment.

4.3. Biochemical, clinical and image control

With a median follow-up of 43 months (range, 6–103 months) since recurrence or persistence treated with radiation therapy, 54 patients were alive (96.4%), 2 died for other medical causes. At last follow-up, 51 patients (87.9%) had no signs or symptoms of clinical activity, and 39 patients (67.2%) had normal biochemical hormone evaluation. Median residual and pituitary diameter size (width, height, and length) and volume on MRI at 3–6 months, and last follow-up MRI was significantly smaller than MRI before RT. Tumor control at 5 years was 91.1%.

4.4. PTV: variations in dosimetric distribution with 4 plans

In Table 2 and Fig. 1, Fig. 2, we show differences between the 4 plans (C3D, C3D FFF, IMRT, and VMAT) and PTV dose distribution. Since a comparison was made with Friedman test ranks, rows with p value <0.05 identified values of PTV coverage (Table 2) or OAR constraint (Table 3) in which at least one of the planning techniques differs from the others. To further identify which RT technique differs from which other, pairwise comparisons using the Nemenyi multiple comparison test was used. The following results were obtained from these comparisons.

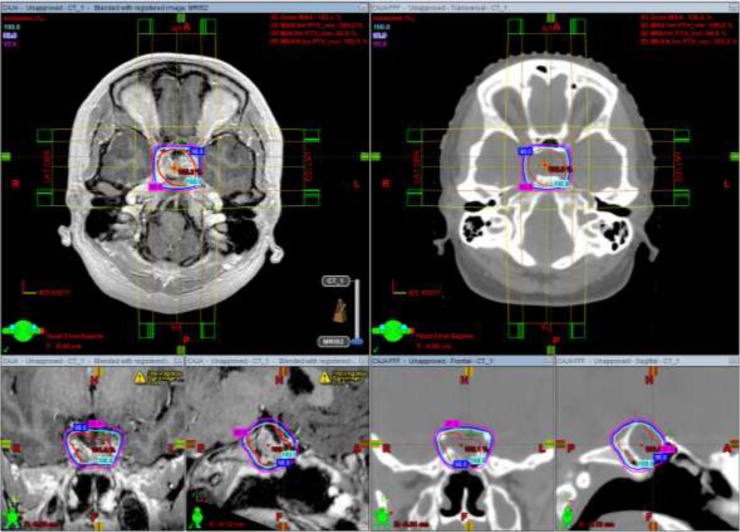

Fig. 1.

Isodose curves of D100% (cyan), D98% (blue) and D95% (magenta) with C3D (left) and C3D FFF (right) with axial, coronal, and sagittal views of MRI and CT, respectively. Abbreviations: C3D, conformal 3D radiotherapy; C3D FFF, conformal 3D radiotherapy flattening filter-free; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

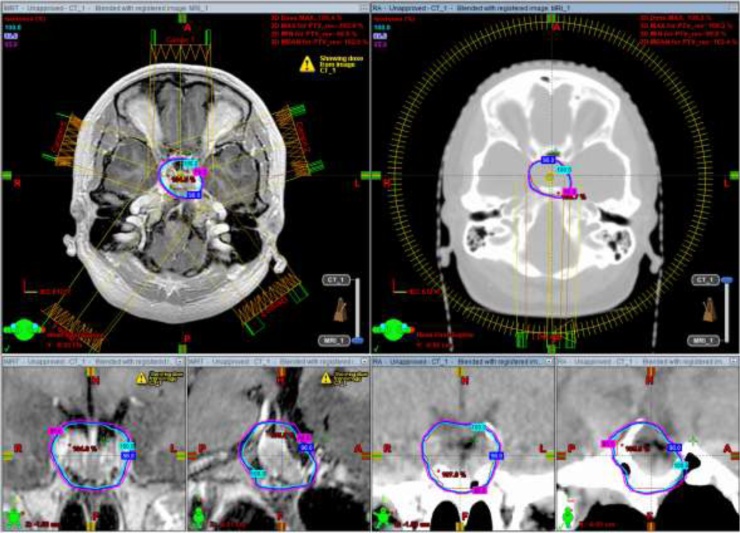

Fig. 2.

Isodose curves of D100% (cyan), D98% (blue) and D95% (magenta) with IMRT (left) and VMAT (right) with axial, coronal and sagittal views of MRI and CT, respectively. Abbreviations: IMRT, modulated intensity radiotherapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article).

Table 3.

Median maximum and mean dose (in cGy) and median D2% to each organ at risk.

| PTV | C3D | C3D FFF | IMRT | VMAT | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left optic nerve | Max | 2938 233–5603 |

2883 204–5576 |

2604 399–5595 |

2309 423–5399 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 455 99–3495 |

398 90k3383 |

992 173–3366 |

1023 190−3095 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 1788 194–5540 |

1674 171–5483 |

2031 335–5489 |

1934 369–5184 |

<0.0001 | |

| Right optic nerve | Max | 3130 258–5652 |

3037 227–5805 |

2766 459–5582 |

2372 342–5457 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 706 92–5074 |

648 84–5143 |

1033 214–4124 |

1037 163–4248 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 2570 182–5624 |

2455 162k5770 |

2271 389–5509 |

1974 291–5333 |

<0.0001 | |

| Chiasm | Max | 5384 2982–5785 |

5381 2923−6008 |

5325 2994–5640 |

5338 2633–5471 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 3712 1488–5733 |

3622 1374k5982 |

3233 1105–5504 |

2975 953–5400 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 5279 2740–55,756 |

5264 2646–6006 |

5210 2786–5520 |

5131 2275–5407 |

<0.0001 | |

| Left lens |

Max | 73 28–1262 |

63 25–675 |

145 39–209 |

156 28–340 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 55.6 25.9–325.7 |

48 22–262 |

88 37–169 |

96 26–215 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 70.5 27.5–954.1 |

58 24–479 |

126 39–197 |

140 27–289 |

<0.0001 | |

| Right lens | Max | 77.0 27.2–1400.2 |

62 25–1393 |

133 38–241 |

165 27–282 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 55.2 24.3–556.5 |

47 21–494 |

82 32–199 |

99 26–225 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 72.6 26.5–1187.2 |

59 24–1155 |

117 37–222 |

153 27–264 |

<0.0001 | |

| Brainstem | Max | 4942 3072–5606 |

4891 49–5661 |

4504 1799–5452 |

3851 1586–5604 |

<0.0001 |

| Mean | 1772 978–2893 |

1758 44–2908 |

1158 514–2411 |

906 412–2255 |

<0.0001 | |

| D2% | 3425 2894–5357 |

3311 47–5321 |

3271 1265–4910 |

2632 1309–4783 |

<0.0001 | |

| Left cochlea | Max | 498 73–5065 |

533 68–4866 |

1896 151–3614 |

1559 129–4697 |

<0.001 |

| Mean | 227 54–3764 |

212 51–3551 |

1248 101–2897 |

1559 129–4697 |

<0.001 | |

| D2% | 424 70–4952 |

427 65–4743 |

1809 134–3531 |

1513 119–4426 |

<0.001 | |

| Right cochlea | Max | 631 85–4957 |

608 101–4805 |

1944 156–4800 |

1678 145–4505 |

<0.001 |

| Mean | 230 58–3206 |

201 55–3164 |

1383 100–3363 |

1219 97–3216 |

<0.001 | |

| D2% | 484 78–4712 |

447 95–4564 |

1831 140–4552 |

1574 134–4027 |

<0.001 | |

| Left eye | Max | 353 68–2809 |

303 63–2744 |

832 119–2354 |

882 91–1879 |

<0.001 |

| Mean | 82 31–835 |

72.4 29–843 |

261 54–486 |

265 39–705 |

<0.001 | |

| D2% | 224 51–2653 |

193 48–2604 |

724 95–1442 |

686 71–1624 |

<0.001 | |

| Right eye | Max | 345 70–3321 |

293 62–3273 |

841 137–1934 |

893 95–2356 |

<0.001 |

| Mean | 73 25–1198 |

62 23k1170 |

248 53k531 |

281 39–794 |

<0.001 | |

| D2% | 212 49–2848 |

178 43–2879 |

731 95–1377 |

745 74k1918 |

<0.001 | |

Abbreviations: C3D, conformal 3D radiotherapy; C3D FFF, conformal 3D radiotherapy flattening filter-free; IMRT, modulated intensity radiotherapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy.

PTV maximum dose was significantly higher in conformal 3D FFF and VMAT. PTV minimum dose was significantly lower with VMAT. Median PTV dose was lower with IMRT and VMAT. PTV D98% (in cGy and %) was significantly higher with IMRT compared to C3D FFF and VMAT. Median PTV D50% (in cGy and %) is significantly lower for VMAT and IMRT versus C3D and C3D FFF. Median PTV D2% (in cGy and %) was significantly lower with IMRT than C3D and VMAT, and all were lower than C3D FFF. Median V95% was lower with VMAT versus IMRT. Median PTV V107% was significantly lower with IMRT and higher with C3D FFF. However, these differences, although significant, are subtle differences limited to 1–2 Gy. A significantly better HI was achieved with IMRT considering both formulas, and a better CI was achieved with IMRT than VMAT, and both showed a better conformity than C3D and C3D FFF.

4.5. OARs: variations in dose and constraint compliance with 4 plans

Table 3 shows significantly lower maximum doses and D2% (within constraints) to optic nerves achieved with VMAT, with higher mean doses with VMAT and IMRT compared to C3D FFF and C3D plans. Chiasm received significantly lower maximum, mean dose and D2% with VMAT compared to IMRT, and higher dose with C3D and C3D FFF. Significantly lower maximum and median doses and D2% (within constraints) were delivered to the lens with IMRT and VMAT, and to the brainstem with VMAT. The dose was significantly lower (within constraints) to the cochlea with IMRT in those in which PTV extended to involve it and lower with VMAT when PTV did not extend to the temporal bone. The maximum, mean, and D2% to the eyes was significantly lower with IMRT and VMAT.

In the analysis of patients according to neck position, significantly (p < 0.0001) median lower doses were achieved with neck extreme flexion to the optic nerves with C3D (mean 496 vs. 1158 cGy) and C3D FFF (mean, 455 vs. 1058 cGy); to the lens, the mean, maximum, and D2% with C3D (D2% 64 vs. 133 cGy), C3D FFF (D2% 54 vs. 109 cGy), and VMAT (D2% 121 vs. 190 cGy, p < 0.0001); to the brainstem mean and D2% with C3D (D2% 3332 vs. 4320 cGy), and C3D FFF (D2% 3272 vs. 4259 cGy); and to the eye maximum, mean, and D2% with C3D (D2% 143 vs. 472 cGy) and C3D FFF (D2% 129 vs. 403 cGy). There were no differences in the OAR doses received with IMRT independently of neck position.

When the analysis was limited to patients with PTV ≤ 10 cm3, neck extreme flexion showed significantly reduced dose to the lenses with C3D (D2% 83 vs. 53 cGy; p = 0.047) and C3D FFF (D2% 46 vs. 69 cGy; p = 0.035); and, to the eyes with C3D (D2% 139 vs. 339 cGy; p = 0.019) and C3D FFF (D2% 120 vs. 294 cGy; p = 0.017). For VMAT with neck extreme flexion, significantly lower mean dose to the chiasm (2882 vs. 3698 cGy; p = 0.023), D2% to the lens (118 vs. 181 cGy; p = 0.001) but significantly higher mean dose to the cochlea (1149 vs. 803 cGy; p = 0.022). For IMRT, a treatment plan with CT simulation with neck extreme flexion was associated with lower D2% (5171 vs. 5306 cGy; p = 0.032)

The position of the neck in extreme flexion showed that it helps in planning mainly with VMAT by allowing the use of only one arc while achieving the desired conformity, decreasing the treatment time, while allowing greater protection to the organs of risk using C3D, C3DFFF.

5. Discussion

CFRT has traditionally been used in patients with residual or recurrent secreting and nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas that did not respond to prior medical management and/or surgery, resulting in variable long-term tumor control. Recurrence rates are 80%–90% at 10 years and 75%–90% at 20 years.17, 18, 19, 20 The RT may reduce recurrence rates to 6% after 10 years and 12% after 20 years.19,21,23 Despite notably improved tumor growth control, there are concerns about potential late RT-induced toxicity and a delay to achieve adequate hormone control in secreting adenomas.20,21 Our patients’ clinical outcomes showed that the median residual and pituitary diameter (width, height, and length) and volume on MRI at 3–6 months and last follow-up MRI were significantly smaller than those visible on MRI before RT (p < 0.0001), with a tumor control at 5 years of 91.1%.

Delivering highly conformal doses to target volumes and reducing dose to surrounding healthy tissues could potentially increase tumor control and reduce adverse effects. These can be achieved with newer RT techniques such as SRS, VMAT, and IMRT; however, limited evidence has been published regarding different RT treatment modalities.22 In our study, 4 treatment techniques for pituitary adenoma were compared, and all provided acceptable dosimetric results with adequate coverage to PTV. In FF and FFF C3D plans, using the same field setup, we confirmed no relevant differences in target coverage and OAR dose constraints. FF offer uniform and homogeneous dose distribution which has justified its use in C3D planning, however, it has also been demonstrated that the use of FFF mode is feasible in C3D and that it could even reduce peripheral doses.24 The advantages of using FFF for modern planning techniques (such as IMRT and VMAT) are the inhomogeneous dose distribution, the MLC leakage reduction and the increased dose rate. This increase in dose rate is especially beneficial in IMRT due to the decrease in treatment time.

Significantly (albeit slight) better homogeneity index was achieved with IMRT, and better conformity was gained with VMAT compared with IMRT. Overall, VMAT was more conformal and offered better sparing of OARs. VMAT also had a faster treatment time. PTV maximum dose was higher in C3D FFF and VMAT. PTV minimum dose was lower with VMAT. Target-volume coverage was acceptable for all the techniques, with the 98% isodose covering a higher volume for IMRT with 99% (range, 98.2%–99.6%; p < 0.001). We found that VMAT and IMRT provided the best target volume conformity (CI of 1.01 and 1.06, respectively; p < 0.0001). As a result of this better conformity, a smaller volume of healthy brain tissue received high-dose radiation.

The quality of planning relies heavily on dose homogeneity, especially when treating pituitary adenomas where OARs are partially inside the PTV. Intra- and interfraction uncertainties can cause serious adverse events when dosing near these OARs. In our study, the IMRT and C3D plans, regardless of FFF, gave the best homogeneity (HI of 0.06 with IMRT vs. 0.07 with VMAT vs. 0.08 with 3D vs. 0.09 with 3D FFF; p < 0.0001). However, these differences, although significant, are subtle.

Another important aspect for RT for pituitary adenoma is to spare critical OARs.14 Dosimetric constraints were maintained for all OARs using IMRT and VMAT. The dose was significantly lower (within constraints) to the cochlea with IMRT in those in whom PTV extended to areas near it, and lower with VMAT when PTV did not extend to the temporal bone. In our study, although the average dose received by the cochlea was lower with C3D and C3D FFF, the restriction dose was respected only in patients treated with VMAT. Several studies have attempted to correlate mean cochlear dose to hearing loss, reporting a significant increase in hearing loss when the cochlear dose exceeds 45–50 Gy.22,23

VMAT allows for the administration of significantly lower doses to the optical pathway, which carries a lower risk of radiation-induced neuropathy (RION). In CFRT, the incidence of RION primarily depends on the total radiation dose.25,26 Certain baseline factors, such as diabetes mellitus, gender, tumor compression, or previous chemotherapy, have been reported to be associated with an increased risk. Typically, a maximum point dose (Dmax) of up to 54–55 Gy in 1.8- to 2-Gy fractions is recommended based on the observation that the incidence of RION increases markedly at doses >60 Gy, although instances of presumed RION have also been reported at lower doses.27 In a review of optic pathway radiation induced toxicity by Mayo et al.,28 complications were reported with maximum doses as low as 46 Gy with conventional fractionation according to previously reported studies.29, 30, 31 In our study, significantly lower maximum dose fulfilling constraints were achieved with VMAT and IMRT.

Lower doses with IMRT or VMAT techniques (to normal tissue surrounding PTV) are associated with an increase in the incidence of solid cancers in long-term survivors.32,33 We did not compare low dose volumes between the four treatment plans. However, low dose effects should still be considered. In a retrospective case series, the cumulative incidence of gliomas and meningiomas following RT for pituitary adenomas is 2% at 20 years.34,35 Wiggenraad et al.36 found similar results; however, they noted that more monitor units were needed with IMRT, even though they found no statistically significant difference between IMRT and VMAT with respect to the volume of irradiated brain tissue.

Neck extreme flexion during CT simulation significantly reduced the RT dose to the lens when planning with C3D, C3D FFF, and VMAT. Also, the doses to the optic nerves, brainstem, and eyes were significantly reduced when planning with C3D and C3D FFF. Therefore, when using conventional planning techniques (C3D and C3D FFF), it is desirable to do a simulation with neck extreme flexion. However, for IMRT planning, there were no dose differences between neck position in extreme or neutral flexion. Therefore, with IMRT a neutral neck position would be ideal as the neutral position carries a lower risk for set-up errors.

6. Conclusions

Our results confirmed that EBRT in pituitary adenomas using IMRT, VMAT, C3D, C3FFF provide adequate coverage to the target. VMAT with a single arc (in patients with neck flexion at CT simulation) or in complete arc (in those without neck flexion) had a better compliance with desired dosimetric goals, such as target coverage and normal structures dose constraints, as well as shorter treatment time. Neck extreme flexion may have benefits in treatment planning for better preservation of organs at risk. C3D with extreme neck flexion is an appropriate treatment option when other treatment techniques are not available.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

Contributor Information

Rubi Ramos-Prudencio, Email: rub18_ramos@hotmail.com.

Christian Haydée Flores-Balcazar, Email: chrishaydee@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Ostrom Q.T., Gittleman H., Liao P. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2010–2014. Neuro Oncol. 2017;19(Suppl. 5):v1–v88. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varlamov E.V., McCartney S., Fleseriu M. Functioning pituitary adenomas — current treatment options and emerging medical therapies. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2019;15(1):30–40. doi: 10.17925/EE.2019.15.1.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheick S., Amdur R.J., Kirwan J.M. Long-term outcome after fractionated radiotherapy for pituitary adenoma: the curse of the secretory tumor. Am J Clin Oncol. 2016;39:49–54. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nieman L.K., Biller B.M., Findling J.W. Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100:2807–2831. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Minniti G., Flickinger J., Tolu B., Paolini S. Management of nonfunctioning pituitary tumors: radiotherapy. Pituitary. 2018;21(2):154–161. doi: 10.1007/s11102-018-0868-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pashtan I., Oh K., Loeffler J.S. Radiation therapy in the management of pituitary adenomas. In: Fliers E., Korbonits M., Rominj J.A., editors. Handbook of clinical neurology, vol. 124 (3rd series) clinical neuroendocrinology. Elsevier; London: 2014. pp. 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morana G., Maghnie M., Rossi A. Pituitary tumors: advances in neuroimaging. Endocr Dev. 2010;17:160–174. doi: 10.1159/000262537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guckenberger M., Baier K., Guenther I. Reliability of the bony anatomy in image-guided stereotactic radiotherapy of brain metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scoccianti S., Detti B., Gadda D. Organs at risk in the brain and their dose-constraints in adults and in children: a radiation oncologist’s guide for delineation in everyday practice. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minniti G., Osti M.F., Niyazi M. Target delineation and optimal radiosurgical dose for pituitary tumors. Radiat Oncol. 2016;11(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s13014-016-0710-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H., Potrebko P., Rivera A. Tumor volume threshold for achieving improved conformity in VMAT and gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for vestibular schwannoma. Radiother Oncol. 2015;115(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emami B., Lyman J., Brown A. Tolerance of normal tissue to therapeutic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:109–122. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentzen S.M., Constine L.S., Deasy J.O. Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC): an introduction to the scientific issues. Int J Radiat Oncol Boil Phys. 2010;76:S3–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gondi V., Pugh S.L., Tome W.A. Preservation of memory with conformal avoidance of the hippocampal neural stem-cell compartment during whole-brain radiotherapy for brain metastases (RTOG 0933): a phase II multi-institutional trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3810–3816. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prescribing, recording, and reporting photon-beam intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT): contents. J ICRU. 2010;10(1) doi: 10.1093/jicru/ndq002. NP. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feuvret L., Noël G., Mazeron J.-J., Bey P. Conformity index: a review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(2):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCollough W.M., Marcus R.B., Jr., Rhoton A.L., Jr., Ballinger W.E., Million R.R. Long-term follow-up of radiotherapy for pituitary adenoma: the absence of late recurrence after greater than or equal to 4500 cGy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21:607–614. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90677-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brada M., Rajan B., Traish D. The long-term efficacy of conservative surgery and radiotherapy in the control of pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1993;38:571–578. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1993.tb02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsang R.W., Brierly J.D., Panzarella T., Gospodarowicz M.K., Sutcliffe S.B., Simpson W.J. Radiation therapy for pituitary adenoma: treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30:557–565. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90941-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zierhut D., Flentje M., Adolph J., Erdmann J., Raue F., Wannenmacher M. External radiotherapy of pituitary adenomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minniti G., Traish D., Ashley S., Gonsalves A., Brada M. Fractionated stereotactic conformal radiotherapy for secreting and nonsecreting pituitary adenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:542–548. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong D.S., Lee J.I., Lim D.H. The efficacy of fractionated radiotherapy and stereotactic radiosurgery for pituitary adenomas (long-term results of 125 consecutive patients treated in a single institution) Cancer. 2007;110(4):854–860. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan C.C., Eisbruch A., Lee J.S. Prospective study of inner ear radiation dose and hearing loss in head and neck cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:1393–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kretschmer M., Sabatino M., Blechschmidt A. The impact of flattening-filter-free beam technology on 3D conformal RT. Radiat Oncol. 2013;8(133) doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-8-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng X., Yang Z., Liu R. The maximum tolerated dose of gamma radiation to the optic nerve during gamma knife radiosurgery in an animal study. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2013;91:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000343212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brecht S., Boda-Heggemann J., Budjan J. Radiation-induced optic neuropathy after stereotactic and image guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) Radiother Oncol. 2019;134:166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doroslovacki P., Tamhankar M.A., Liu G.T. Factors associated with occurrence of radiation-induced optic neuropathy at ‘‘safe” radiation dosage. Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33(4):581–588. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2017.1346133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayo C., Martel M.K., Marks L.B., Flickinger J., Nam J., Kirkpatrick J. Radiation dose–volume effects of optic nerves and chiasm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76(3):S28–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Bergh A.C., Dullaart R.P., Hoving M.A. Radiation optic neuropathy after external beam radiation therapy for acromegaly. Radiother Oncol. 2003;68:95–100. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8140(03)00202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackley H.B., Reddy C.A., Lee S.Y. Intensity-modulated radiotherapy for pituitary adenomas: the preliminary report of the Cleveland Clinic experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;67:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aristizabal S., Caldwell W.L., Avila J. The relationship of time-dose fractionation factors to complications in the treatment of pituitary tumors by irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1977;2:667–673. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(77)90046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gondi V., Tomé W.A., Mehta M.P. Why avoid the hippocampus? A comprehensive review. Radiother Oncol. 2010;97:370–376. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall E.J. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy, protons, and the risk of second cancers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brada M., Ford D., Ashley S. Risk of second brain tumour after conservative surgery and radiotherapy for pituitary adenoma. BMJ. 1992;304(6838):1343–1346. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6838.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loeffler J.S., Niemierko A., Chapman P.H. Second tumor after radiosurgery: tip of the iceberg or a bump in the road? Neurosurgery. 2003;52(6):1436–1440. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000064809.59806.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiggenraad R.G.J., Petoukhova A.L., Versluis L., van Santvoort J.P.C. Stereotactic radiotherapy of intracranial tumors: a comparison of intensity-modulated radiotherapy and dynamic conformal arc. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1018–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]