Abstract

Background

People with cancer experience a variety of symptoms as a result of their disease and the therapies involved in its management. Inadequate symptom management has implications for patient outcomes including functioning, psychological well‐being, and quality of life (QoL). Attempts to reduce the incidence and severity of cancer symptoms have involved the development and testing of psycho‐educational interventions to enhance patients' symptom self‐management. With the trend for care to be provided nearer patients' homes, telephone‐delivered psycho‐educational interventions have evolved to provide support for the management of a range of cancer symptoms. Early indications suggest that these can reduce symptom severity and distress through enhanced symptom self‐management.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of telephone‐delivered interventions for reducing symptoms associated with cancer and its treatment. To determine which symptoms are most responsive to telephone interventions. To determine whether certain configurations (e.g. with/without additional support such as face‐to‐face, printed or electronic resources) and duration/frequency of intervention calls mediate observed cancer symptom outcome effects.

Search methods

We searched the following databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 1); MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to January 2019); Embase via OVID (1980 to January 2019); (CINAHL) via Athens (1982 to January 2019); British Nursing Index (1984 to January 2019); and PsycINFO (1989 to January 2019). We searched conference proceedings to identify published abstracts, as well as SIGLE and trial registers for unpublished studies. We searched the reference lists of all included articles for additional relevant studies. Finally, we handsearched the following journals: Cancer, Journal of Clinical Oncology, Psycho‐oncology, Cancer Practice, Cancer Nursing, Oncology Nursing Forum, Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, and Palliative Medicine. We restricted our search to publications published in English.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared one or more telephone interventions with one other, or with other types of interventions (e.g. a face‐to‐face intervention) and/or usual care, with the stated aim of addressing any physical or psychological symptoms of cancer and its treatment, which recruited adults (over 18 years) with a clinical diagnosis of cancer, regardless of tumour type, stage of cancer, type of treatment, and time of recruitment (e.g. before, during, or after treatment).

Data collection and analysis

We used Cochrane methods for trial selection, data extraction and analysis. When possible, anxiety, depressive symptoms, fatigue, emotional distress, pain, uncertainty, sexually‐related and lung cancer symptoms as well as secondary outcomes are reported as standardised mean differences (SMDs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and we presented a descriptive synthesis of study findings. We reported on findings according to symptoms addressed and intervention types (e.g. telephone only, telephone combined with other elements). As many studies included small samples, and because baseline scores for study outcomes often varied for intervention and control groups, we used change scores and associated standard deviations. The certainty of the evidence for each outcome was interpreted using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

Thirty‐two studies were eligible for inclusion; most had moderate risk of bias,often related to blinding. Collectively, researchers recruited 6250 people and studied interventions in people with a variety of cancer types and across the disease trajectory, although many participants had breast cancer or early‐stage cancer and/or were starting treatment. Studies measured symptoms of anxiety, depression, emotional distress, uncertainty, fatigue, and pain, as well as sexually‐related symptoms and general symptom intensity and/or distress.

Interventions were primarily delivered by nurses (n = 24), most of whom (n = 16) had a background in oncology, research, or psychiatry. Ten interventions were delivered solely by telephone; the rest combined telephone with additional elements (i.e. face‐to‐face consultations and digital/online/printed resources). The number of calls delivered ranged from 1 to 18; most interventions provided three or four calls.

Twenty‐one studies provided evidence on effectiveness of telephone‐delivered interventions and the majority appeared to reduce symptoms of depression compared to control. Nine studies contributed quantitative change scores (CSs) and associated standard deviation results (or these could be calculated). Likewise, many telephone interventions appeared effective when compared to control in reducing anxiety (16 studies; 5 contributed quantitative CS results); fatigue (9 studies; 6 contributed to quantitative CS results); and emotional distress (7 studies; 5 contributed quantitative CS results). Due to significant clinical heterogeneity with regards to interventions introduced, study participants recruited, and outcomes measured, meta‐analysis was not conducted.

For other symptoms (uncertainty, pain, sexually‐related symptoms, dyspnoea, and general symptom experience), evidence was limited; similarly meta‐analysis was not possible, and results from individual studies were largely conflicting, making conclusions about their management through telephone‐delivered interventions difficult to draw. Heterogeneity was considerable across all trials for all outcomes.

Overall, the certainty of evidence was very low for all outcomes in the review. Outcomes were all downgraded due to concerns about overall risk of bias profiles being frequently unclear, uncertainty in effect estimates and due to some inconsistencies in results and general heterogeneity.

Unsubstantiated evidence suggests that telephone interventions in some capacity may have a place in symptom management for adults with cancer. However, in the absence of reliable and homogeneous evidence, caution is needed in interpreting the narrative synthesis. Further, there were no clear patterns across studies regarding which forms of interventions (telephone alone versus augmented with other elements) are most effective. It is impossible to conclude with any certainty which forms of telephone intervention are most effective in managing the range of cancer‐related symptoms that people with cancer experience.

Authors' conclusions

Telephone interventions provide a convenient way of supporting self‐management of cancer‐related symptoms for adults with cancer. These interventions are becoming more important with the shift of care closer to patients' homes, the need for resource/cost containment, and the potential for voluntary sector providers to deliver healthcare interventions. Some evidence supports the use of telephone‐delivered interventions for symptom management for adults with cancer; most evidence relates to four commonly experienced symptoms ‐ depression, anxiety, emotional distress, and fatigue. Some telephone‐delivered interventions were augmented by combining them with face‐to‐face meetings and provision of printed or digital materials. Review authors were unable to determine whether telephone alone or in combination with other elements provides optimal reduction in symptoms; it appears most likely that this will vary by symptom. It is noteworthy that, despite the potential for telephone interventions to deliver cost savings, none of the studies reviewed included any form of health economic evaluation.

Further robust and adequately reported trials are needed across all cancer‐related symptoms, as the certainty of evidence generated in studies within this review was very low, and reporting was of variable quality. Researchers must strive to reduce variability between studies in the future. Studies in this review are characterised by clinical and methodological diversity; the level of this diversity hindered comparison across studies. At the very least, efforts should be made to standardise outcome measures. Finally, studies were compromised by inclusion of small samples, inadequate concealment of group allocation, lack of observer blinding, and short length of follow‐up. Consequently, conclusions related to symptoms most amenable to management by telephone‐delivered interventions are tentative.

Plain language summary

Telephone interventions for managing symptoms in adults with cancer

Background People with cancer experience a variety of symptoms caused by their disease and its treatment. Symptoms can include depression, anxiety, fatigue and pain. These are often managed, day‐to‐day, by patients or their family members. If symptoms are not well managed, this can lead to other problems, such as difficulties in carrying out everyday tasks, poor sleep and poor quality of life.

Cancer professionals have developed psychological and educational treatments to help people to manage cancer symptoms. These treatments (or interventions) can be delivered by telephone (telephone interventions) in the patients’ homes instead of face‐to‐face in hospital.

What questions does this review aim to answer? This Cochrane Review aimed to answer the following questions.

1. Are telephone interventions for adults with cancer effective in relieving symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment?

2. Which symptoms are most reduced when telephone interventions are used?

3. What parts of telephone interventions have the most impact in reducing cancer symptoms?

In this review, telephone interventions were interventions given only, or mainly, by telephone. They were given by health professionals. As well as telephone contact, they could include face‐to‐face contact, or printed, digital or online information, such as, leaflets, computer programs and websites.

How did we answer these questions? We searched medical databases and journals to find all randomised controlled trials that used a telephone intervention to reduce any cancer symptoms. Randomised controlled trials allocate people randomly to one treatment or another; they provide the most reliable evidence. Studies could compare telephone interventions with another telephone intervention, with another type of intervention (e.g. face‐to‐face), or with usual care. Participants in these studies were adults with any kind of cancer at any stage.

Results We included 32 studies with a total of 6250 participants. Most studies (21) were from the USA. Nine studies recruited women with breast cancer, 11 included people with breast, colorectal, lung, or prostate cancer. Fourteen studies included people with early‐stage cancer. Nurses provided interventions in 24 studies. Only 10 studies delivered interventions solely by telephone, and 16 studies combined telephone calls with other materials (printed or digital). Studies measured symptoms of depression, anxiety, emotional distress, uncertainty, fatigue, pain, sexual symptoms, and breathlessness. They also measured the effect of all the symptoms together (the general symptom experience).

Most studies compared a telephone intervention with usual care alone or usual care with additional support. Eight studies compared two telephone interventions against each other; some also compared these with usual care.

Because the studies were so different from each other, we could not combine the results into one analysis for each symptom. However, some studies measured changes in symptoms using standardised or similar scales. They recorded participants’ scale scores at the beginning of the intervention, during the intervention, and at the end, resulting in a ‘change score’. We analysed the results from studies that recorded change scores.

What does evidence from the review tell us? Twenty‐one studies provided evidence on depression compared to usual care or other interventions, but only nine provided change scores. These found that telephone interventions appeared to reduce symptoms of depression. Likewise, telephone interventions appeared effective compared to usual care or other interventions in reducing anxiety (16 studies; 5 contributed change scores); fatigue (9 studies; 6 contributed change scores); and emotional distress (7 studies; 5 contributed change scores).

Evidence for other symptoms was limited, making it difficult to draw conclusions.

Certainty of the evidence Telephone interventions appear to relieve some symptoms of cancer and cancer treatment, however, the studies were small and very different from each other, so our confidence (certainty) in the evidence is very low. It is unclear whether telephone interventions alone, or combined with face‐to‐face meetings, or printed or audio materials, are most effective in reducing the many symptoms that people with cancer experience.

Conclusions Telephone interventions are convenient for patients, their families and healthcare workers but the results of our review were not conclusive. Further, rigorous research on this topic would help to answer our review questions.

Search date This review includes evidence published up to January 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Telephone interventions compared with control interventions for symptom management in adults with cancer | ||||

|

Patient or population: individuals with any cancer at any stage Settings: randomised controlled trials Intervention: telephone interventions with or without additional support Comparison: control intervention | ||||

| Outcomes | Risks | Effects of interventions | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

| Anxiety | We could not present illustrative absolute effects because a representative control group risk could not be ascertained from the studies nor from any external source. Furthermore, results were reported in narrative form and varied considerably |

Effect measures (using change score (CS)) ranged from: SMD ‐5.1 (95% CI ‐6.1 to ‐4.1) for breast cancer to SMD ‐0.3 (95% CI ‐0.3 to 0.9) for prostate cancer Other cancer sites including colorectal and lung and trials including participants with mixed cancers The 5 trials reporting data where change scores could be calculated were generally very heterogeneous in terms of demographics, including age and gender (gender specific or mixed cancers), FIGO stage (early or advanced disease), and delivery of interventions and controls. This may have differed in the number of telephone calls and whether additional management components were used in intervention arms, and in controls being sufficiently different to consider any data synthesis methods |

277 participants

(5 studies) Sample sizes were often small, and baseline outcome values for intervention and control groups largely differed widely in 11 further studies. Therefore displaying only studies that used change scores seemed appropriate, and in future updates of the review, meta‐analytical approaches will be attempted |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c |

| Depression |

Effect measures (CS) ranged from: SMD ‐2.2 (95% CI ‐2.7 to ‐1.7) for colorectal cancer to SMD 0.3 (95% CI 0.04 to 0.5) for mixed cancers Other cancer sites including breast, lung, and prostate cancer. There was scope in the breast and mixed cancer subgroups to potentially pool results, but even within these more restrictive analyses, there was considerable heterogeneity, imprecision, and inconsistency across trials. Therefore results were reported by single trials, and results were presented narratively The 9 trials reporting data where change scores could be calculated were generally very heterogeneous in terms of demographics, including age and gender (gender specific or mixed cancers), FIGO stage (early or advanced disease), and delivery of interventions and controls. This may have differed in the number of telephone calls and whether additional management components were used in intervention arms, and in controls being sufficiently different to consider any data synthesis methods |

1059 participants

(9 studies) Sample sizes were often small, and baseline outcome values for intervention and control groups largely differed widely in 12 further studies. Therefore displaying only studies that used change scores seemed appropriate, and in future updates of the review, attempts at meta‐analysis will be made |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |

| Fatigue |

Effect measures (CS) ranged from: SMD ‐0.9 (95% CI ‐1.5 to ‐0.3) for breast cancer to SMD 0.0 (95% CI ‐0.2 to 0.2) for mixed cancers Another cancer site, including prostate cancer. There was scope in the mixed cancer subgroup to potentially pool results, but even within these more restrictive analyses, there were sufficient clinical differences between trials to justify not using this approach. Therefore results were reported by single trials and are presented narratively The 6 trials reporting data where change scores could be calculated were generally very heterogeneous in terms of demographics, including age and gender (gender specific or mixed cancers), FIGO stage (early or advanced disease), and delivery of interventions and controls |

895 participants

(6 studies) Sample sizes were often small, and baseline outcome values for intervention and control groups largely differed widely in 3 further studies. Therefore displaying only studies that used change scores seemed appropriate, and in future updates of the review, attempts at meta‐analysis will be made |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |

| Emotional distress |

SMDs (CS) in each individual trial all indicated uncertainty as to whether telephone interventions or control interventions were best for minimising emotional distress (all estimates were imprecise) Cancer sites included breast, prostate, and mixed cancers. There was scope in the breast cancer subgroup to potentially pool results, but there were sufficient clinical differences between the 2 trials in terms of including participants at different stages and ages to justify not using this approach. Therefore results were reported by single trials and are presented narratively The 5 trials reporting data where change scores could be calculated were generally very heterogeneous in terms of demographics, including age and gender (gender specific or mixed cancers), FIGO stage (early or advanced disease), and delivery of interventions and controls. This may have differed in the number of telephone calls and whether additional management components were used in intervention arms, and in controls being sufficiently different to consider any data synthesis methods |

968 participants

(5 studies) Sample sizes were often small, and baseline outcome values for intervention and control groups largely differed widely in 2 further studies. Therefore displaying only studies that used change scores seemed appropriate, and in future updates of the review, attempts at meta‐analysis will be made |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |

| Other outcomes included uncertainty, pain, sexually related symptoms, dyspnoea, and general symptoms. Data for any of these outcomes were not pooled due to considerable heterogeneity across all aspects. Magnitudes of effect were not reported | Studies for each outcome ranged from 2 to 6 (10 were included in the wider 'general symptoms' outcome) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; CS: change score; FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High certainty: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate certainty: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low certainty: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low certainty: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

aDowndraded by one level due to concerns about overall risk of bias being unclear or high.

bDowndraded by one level due to concerns about precision.

cDowndraded by one level due to inconsistencies in results and general heterogeneity.

Background

Description of the condition

People with cancer often experience a variety of symptoms as a result of their disease and its treatment (Harrington 2010;Kim 2012;Van Lancker 2014). As much cancer treatment is delivered on an ambulatory basis, patients and family members are largely responsible for their day‐to‐day management (Dodd 2000;McPherson 2014). Inadequate symptom management can result in early discontinuation of, or delays in, treatment (Cleeland 2009), and it has considerable implications for patient outcomes including functioning, psychological well‐being, and quality of life (Dodd 2001;Glover 1995;Laugsand 2011).

Symptoms often manifest concurrently and appear related to one another. Symptom clusters ‐ where three or more related symptoms manifest concurrently (Dodd 2001) ‐ have become the subject of much contemporary research, with some evidence suggesting that they may have prognostic capabilities or may influence cancer outcomes (Cheville 2010). It is estimated that 40% of oncology patients experience more than one symptom at any one time (Kim 2009), and that as disease progresses, symptom burden rises. One study of 1000 people with cancer admitted to a palliative care unit determined that people experienced differing numbers of symptoms on admission, ranging between 1 and 29. However, the median number of symptoms that people presented with was 11 (Walsh 2000).

Attempts to reduce the incidence and severity of cancer symptoms have involved the development and testing of psycho‐educational interventions to enhance patients' symptom self‐management. These interventions may include therapeutic elements such as information exchange, problem‐solving, coping skills training, and facilitating expression of emotions and concerns (Barsevick 2002). Although traditionally delivered face‐to‐face, interventions are increasingly being delivered by telephone (e.g. Freeman 2015), online (e.g. Steel 2016), or by mobile phone (e.g. Kearney 2009). These alternative modes of delivery are convenient for health professionals and patients alike. Integral to these is the delivery of supportive, interactive care provided by health professionals that provides patients with information about symptom management and support and encouragement in adopting effective self‐care.

Description of the intervention

This review evaluates the effectiveness of telephone interventions delivered to people with cancer, with the aim of improving symptoms of the disease and/or its treatment. These interventions are typically educational or psychologically based in nature and may entail cognitive‐behavioural, motivational, or supportive elements to facilitate patient management of symptoms. They can be delivered to patients alone or in conjunction with informal carers (family or friends). Further, they can be supplemented with face‐to‐face contact with health professionals and digital/online/printed educational materials.

Such interventions are gaining in popularity as health systems worldwide are challenged fiscally from having to care for increasingly ageing populations with limited available resources and soaring pharmacological and other healthcare costs. Interventions delivered by telephone are feasible and acceptable to patients and offer health services a cheaper alternative to interventions delivered face‐to‐face.

How the intervention might work

Telephone interventions for symptom management may vary in terms of the symptom(s) they address, the theoretical frameworks underpinning them, the length of time over which they are delivered, and the training/qualifications of persons providing the telephone contact. However, whatever their make‐up, telephone interventions are united in their potential for providing timely information and support to promote behaviour change and/or adherence with prescribed medications and/or recommended self‐care, thereby enhancing patient outcomes and quality of life.

Why it is important to do this review

Although historically, information and support in managing symptoms were delivered face‐to‐face, increasingly this is not the case. The trend is for care to be provided nearer patients' homes, meaning that people with cancer are typically seeing hospital‐based staff less often. Thus, there is a greater requirement for information and support in symptom management to be provided by other means, such as by telephone. Telephone interventions have been developed for a range of cancer symptoms (Scura 2004). Early indications suggest that these interventions have benefit, as they:

reduce symptom severity;

reduce symptom distress;

enhance self‐management of symptoms; and

facilitate adaptation to symptoms.

However, evidence published to date has not been subject to rigorous systematic review. Four previous literature reviews have explored allied topics. Cox 2003 and Dickinson 2014 appraised and synthesised literature related to cancer follow‐up (by telephone and through use of technology, respectively). Gotay 1998 reviewed outcomes of psychosocial support provided by telephone, and Galway 2012 reviewed psychosocial interventions (but did not focus on their delivery by telephone). Thus, none of these reviews explicitly analysed literature specifically evaluating telephone‐delivered interventions for cancer symptoms. Further, the Gotay 1998 and Cox 2003 reviews are very much out‐of‐date. Thus, there is good justification to undertake a Cochrane systematic review to explore the effectiveness of telephone‐delivered interventions for cancer symptoms.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of telephone‐delivered interventions for reducing symptoms associated with cancer and its treatment. To determine which symptoms are most responsive to telephone interventions. To determine whether certain configurations (e.g. with/without additional support such as face‐to‐face, printed or electronic resources) and duration/frequency of intervention calls mediate observed cancer symptom outcome effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised control trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that:

compared a telephone intervention with other types of interventions (e.g. a face‐to‐face intervention) and/or usual care; or

compared different models of telephone interventions (i.e. with different content) against each other and/or a third arm comprising usual care.

Types of participants

We included studies evaluating telephone interventions for adult men and women (over 18 years of age) with a clinical diagnosis of cancer, regardless of tumour type, stage of disease, type of treatment, and time of recruitment (e.g. before, during, or after anticancer treatment).

We excluded studies that did not focus on cancer patients, or in which only a portion of the sample consisted of cancer patients.

Types of interventions

We included telephone interventions comprising any number of telephone calls delivered by any health or social care professional to cancer patients, with the stated aim of addressing any physical or psychological symptoms of cancer and its treatment. The interventions were referred to by study author(s) as psychological, psychosocial, psycho‐educational, non‐pharmacological, or supportive.

We excluded interventions that:

were not primarily delivered by telephone (e.g. the main form of contact was face‐to‐face and the patient received a single telephone call to monitor progress), although we did include telephone interventions supported with printed/digital/online materials;

aimed to improve patients' general well‐being or adaptation to cancer including managing fear of recurrence (a common concern following cancer) (i.e. interventions that were not aimed primarily at improving cancer symptoms);

evaluated triaging or monitoring care or treatment compliance; or

were not delivered by a health or social care professional, or if details of the background of the person delivering the intervention could not be obtained.

Some interventions within the review incorporated elements other than telephone support. Thus, we categorised them according to whether they comprised solely telephone intervention or included additional supportive elements (e.g. face‐to‐face consultation, printed materials).

Types of outcome measures

We included data related to symptoms associated with cancer and its treatment, measured by standardised instruments that measured symptoms related to cancer with some evidence of validity and reliability.

Primary outcomes

Anxiety (measured by validated instruments such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) or the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI))

Depressive symptoms (measured by validated instruments such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); or the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D))

Emotional distress (measured by validated instruments such as the Profile of Mood States (POMS))

Uncertainty from being diagnosed with, and treated for, cancer (as measured by validated instruments such as the Mischel Uncertainty in Illness Scale)

Fatigue (measured by validated instruments such as the Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI); the Multi‐dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI); or the Piper Fatigue Scale)

Pain (measured by validated instruments such as the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI))

Nausea/ vomiting (measured by validated instruments such as the Index of Nausea, Vomiting and Retching (INVR))

Sexually‐related symptoms (measured by validated instruments such as the Index of Sexual Satisfaction; the Female Sexual Function Index; or the International Index of Erectile Function)

Lung cancer symptoms (measured by validated instruments such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy ‐ Lung Cancer (FACT‐L) or the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) for dyspnoea items)

Secondary outcomes

Symptom experience

Symptom distress (as measured by validated instruments such as the General Symptom Distress Scale)

Search methods for identification of studies

We applied no language restriction for this review, so non‐English publications were to be translated if necessary. This was not needed.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2019, Issue 1), in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 1).

MEDLINE via OVID (1946 to January 2019) (Appendix 2).

Embase via OVID (1980 to January 2019) (Appendix 3).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via Athens (1982 to January 2019).

British Nursing Index (1984 to January 2019).

PsycINFO (1989 to January 2019).

The search strategies are provided in the appendices.

Searching other resources

We searched conference proceedings to identify published abstracts, along with SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) and trial registers for unpublished studies. We searched the reference lists of all included articles to identify additional relevant studies. Finally, we handsearched the following journals from 2007 to 2019.

Cancer.

Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Psycho‐oncology.

Cancer Practice.

Cancer Nursing.

Oncology Nursing Forum.

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management.

Palliative Medicine.

We found no additional studies, We found the studies identified for this review from the databases listed above.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (from the pool of AEH, VHP, AC, KC, and ER) independently assessed the potential relevance of all titles and abstracts identified through the literature searches. We retrieved in full text studies identified by either review author as potentially relevant. Two review authors (of AEH, VHP, AC, and ER) independently assessed each of these studies against the review inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third review author resolved disagreements. Studies that appeared eligible for inclusion but were subsequently judged to not meet the selection criteria were detailed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table, including the specific reason(s) for exclusion (e.g. intervention not delivered by health or social care professionals).

Data extraction and management

We used standardised data extraction forms to extract all available data. Two independent review authors extracted data from each included study. We checked the forms against each other, and when we noted discrepancies, we referred to the original papers. We addressed unresolved discrepancies through discussion and consensus, involving the entire review team when necessary. We contacted study authors to obtain missing data. We extracted and reported on the following data.

Geographic location.

Sample demography (age, gender, tumour type, disease stage, treatment).

Number of participants (including those lost to follow‐up).

Details of randomisation and allocation concealment.

Aim of the intervention.

Details of the intervention (number and frequency of telephone calls; duration of calls; health or social care professional(s) delivering intervention; incorporation of additional elements (face‐to‐face contacts, printed/digital/online materials, email contact)).

Details of control/usual care.

Primary and secondary outcome measures.

Time points at which outcomes were collected and reported (frequency, length of follow‐up).

Reported statistics used to assess validity of results.

Quality assurance processes used to ensure uniformity of intervention delivery (e.g. if intervention providers were trained and/or supervised; if a protocol was used; if an integrity check was described).

When possible, all data extracted were those relevant to an intention‐to‐treat analysis in which participants were analysed in the groups to which they were assigned. When study authors reported on the same piece of research in a series of publications, we considered the main study as the one that depicted the study design in detail and reported on primary outcomes of the study.

We managed data using Review Manager 5.3 (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All review authors independently assessed and reported potential bias for each trial using the data extraction form. A third review author (ER) resolved any conflicts. We used the following criteria from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as a guide for assessment.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participant, providers, outcome assessors, data analysts.

Completeness of outcome data; adequate if less than 20% of patients were lost to follow‐up and reasons for loss to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms.

Selective reporting/intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Other potential sources of bias.

We incorporated results of the assessment into the review through systematic narrative description and commentary about each of these domains. Further, we constructed a risk of bias graph (Figure 1) and a risk of bias summary (Figure 2).

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

We processed data in accordance with guidance provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We analysed all outcomes in the review (anxiety, depressive symptoms, emotional distress, fatigue, pain, uncertainty, sexually‐related issues) as continuous variables, reflecting how they were presented by study authors. As some studies had small samples, and because baseline scores for study outcomes tended to vary between intervention and control, we determined to input change scores and their associated standard deviations into the analyses. We extracted these statistics (when reported) and analysed them alongside (1) baseline, endpoint, and follow‐up mean scores and associated standard deviations of outcomes of interest; (2) P values; and (3) numbers of patients who provided data at each assessment point to estimate the standardised mean difference (SMD) of change scores between treatment arms and its standard error.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for any of the outcomes other than to calculate missing standard deviations of change scores, as few authors reported these. We imputed these values using the approach of Follmann 1992 and Abrams 2005, as detailed in Section 16.1.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. This entailed calculating the correlation coefficient from one study in the symptom group that reported study outcomes in detail ‐ including the standard deviation of the change score ‐ and then using the summary statistics to determine standard deviation of change from baseline across other studies. Two study authors provided sufficient detail to enable calculation of standard deviations of change scores for symptoms of anxiety, depression, emotional distress, and fatigue (Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Ream 2015).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed and found considerable heterogeneity in included studies in terms of (1) interventions introduced; (2) types of participants; and (3) outcomes measured. All interventions were delivered primarily by telephone, but some also incorporated face‐to‐face elements and/or printed, digital, or online materials. Interventions varied in length and frequency and were provided at different times in the cancer journey from treatment to survivorship. There was some standardisation with regards to outcomes measured.

We did not assess methodological and statistical heterogeneity due to considerable clinical heterogeneity across trials. Most studies compared a telephone intervention with usual care, five compared two different interventions with usual care (Badger 2007; Dong 2018; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Thomas 2012), and six compared two interventions without a usual care arm (Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Chambers 2014; Reese 2018; Sikorskii 2007; Watson 2017).

For future updates, we plan to assess statistical heterogeneity between study outcomes by visually inspecting forest plots and by calculating the I² statistic (estimation of the percentage of heterogeneity between trials that cannot be ascribed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003)), and when possible, by conducting subgroup analyses (see later). If we find evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we will investigate and report the possible reasons for this.

Data synthesis

We did not perform meta‐analyses due to considerable heterogeneity.

For future updates of the review, we will do the following.

We will use random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting for all meta‐analyses (DerSimonian 1986).

We will calculate SMDs in outcomes between telephone and control groups (rather than mean differences, if appropriate) to take account of the different scales used across studies to measure different symptom outcomes.

When we are unable to obtain required data to incorporate studies into meta‐analyses, or when we identify insufficient studies related to management of a particular symptom, we will continue to report study findings in a narrative fashion.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For future updates, we will present subgroups on forest plots and will aim to determine whether there is a difference in outcomes according to whether telephone interventions are provided on their own or in conjunction with other elements (e.g. printed materials, face‐to‐face meetings).

Sensitivity analysis

We found an insufficient number of studies (and no meta‐analyses were conducted) to allow review authors to undertake sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of including/excluding studies with high risk of bias (e.g. as a result of inadequate concealment of allocation).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

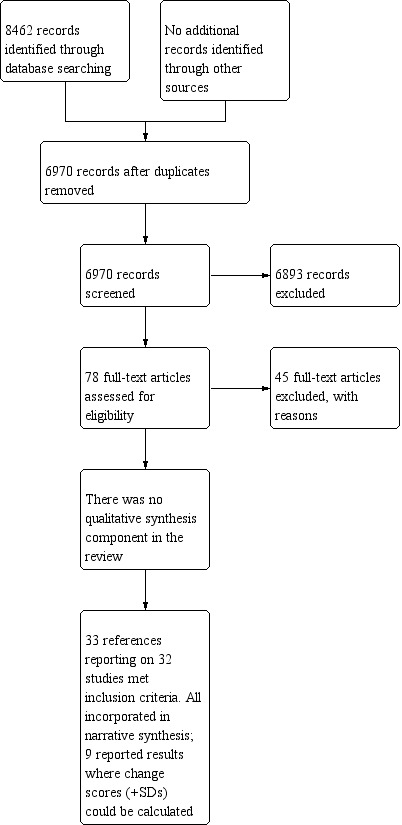

After duplicates and clearly irrelevant articles were eliminated, the electronic and manual search (to January 2019) yielded 78 studies that were potentially eligible for inclusion. After assessing the full text of studies against the inclusion criteria, we excluded 45 studies, leaving 33 studies for inclusion in the review. Gil 2006 was nested in the Mishel 2005 study because it reported on long‐term outcomes of this study. The PRISMA flow chart is presented in Figure 3.

3.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Study design

We included 31 randomised controlled trials (RCTs); the final study employed a repeated‐measures experimental design but did not use random principles for assignment to intervention and control groups (Badger 2005). Ten studies appeared adequately powered (i.e. study authors had determined the sample size required to show effect and had managed to recruit to this target) (Allard 2007; Chambers 2014; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005). Three further studies calculated sample sizes required, but due to under‐recruitment (Livingston 2010; Watson 2017), or higher than predicted attrition (Thomas 2012), these studies were underpowered. Most studies did not specify required sample size to attain adequate power. Five were pilot studies with small sample sizes (Badger 2005; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Reese 2014; Reese 2018).

Most studies compared a telephone‐delivered intervention with usual care. However, of the included studies, five compared an intervention delivered via telephone with an attentional, rather than usual care, control (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Mosher 2016). A further study provided a wait‐list control whereby participants in the control group received the intervention on completion of study assessments (Reese 2014). Four studies compared a telephone‐delivered intervention against augmented usual care, which incorporated additional elements including passive referral to a help line; education/support; nutrition information; or extra information about symptoms reported by patients given to the treating oncologist (Barsevick 2004; Kroenke 2010; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011). Six studies compared two/three interventions but incorporated no control group (Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Chambers 2014; Reese 2018; Sikorskii 2007; Watson 2017). One was an equivalence trial (Watson 2017). Eight studies included three study arms that incorporated telephone‐delivered intervention(s) with alternative intervention with/without a control group (usual care or attentional control) (Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2002; Thomas 2012).

Contact with study authors

We contacted five study authors to clarify issues around provision of the intervention; we subsequently excluded two articles from the review, as data obtained from the study author made it clear that these studies were ineligible. We included three studies once the nature of the interventions and who delivered them were clarified (Badger 2013a; Reese 2014; Reese 2018). Further, we contacted one study author with regards to the Mishel 2002 study, to query numbers of participants in each study arm.

Sample size

Sample sizes ranged from 23 in Reese 2014 to 575 in Mishel 2005, with a total of 6250 cancer patients recruited across the 32 studies.

Setting

Twenty‐one studies were conducted in the USA (Allen 2002; Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Kroenke 2010; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015). Four were conducted in Australia (Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Girgis 2009; Yates 2005), two in Canada (Allard 2007; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007), three in the UK (Molassiotis 2009; Ream 2015; Watson 2017), and one in China (Dong 2018), and one recruited across two countries ‐ Australia and Canada (Livingston 2010).

Participants

Nine studies addressed breast cancer exclusively (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Mishel 2005; Reese 2018; Yates 2005), three solely recruited men with prostate cancer (Bailey 2004; Chambers 2015; Mishel 2002), three recruited only lung cancer patients (Badr 2015; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011), and two recruited only people diagnosed with colorectal cancer (Dong 2018; Reese 2014).

Eleven studies included heterogeneous samples of cancer patients, most commonly with a combination of breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer (Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017); four studies did not specify the type of cancer diagnosis patients had received (Barsevick 2004; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012).

In addition to including people with cancer, 11 studies addressed partners or carers of cancer patients; five included partners of women with breast cancer (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Reese 2018), one included partners of men with prostate cancer (Chambers 2015), one included partners of patients treated for colorectal cancer (Reese 2014), one included partners of people diagnosed with lung cancer (Badr 2015), two included carers of people diagnosed with lung cancer (Mosher 2016; Porter 2011), and one included carers of people with a range of cancers (Chambers 2014). Outcomes for the partners/carers reported in these studies are not included in this review.

Most studies (n = 14) recruited patients with early‐stage cancer. Remaining studies recruited patients with early/locally advanced cancer (n = 2) (Badger 2005; Reese 2018), or people with advanced cancer (n = 4) (Badr 2015; Girgis 2009; Molassiotis 2009; Sherwood 2005), or they did not (n = 11) specify the disease stage for eligible patients (Badger 2005; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Dong 2018; Kroenke 2010; Mosher 2016; Sikorskii 2007; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Thomas 2012; Watson 2017). One study specifically targeted cancer survivors who were between five and nine years post treatment (Mishel 2005).

Most studies recruited consecutive patients irrespective of symptom intensity; few (n = 6) recruited people whose symptoms had attained a threshold level (Chambers 2014; Dong 2018; Kroenke 2010; Mosher 2016; Ream 2015; Reese 2018 ).

Symptoms

Interventions introduced across studies aimed to reduce a variety of symptoms caused by cancer and its treatment; psychological and emotional symptoms were frequently assessed. Sixteen studies measured effects of telephone‐delivered interventions on anxiety (Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Dong 2018; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011: Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005). Depressive symptoms was an outcome measured in 21 studies (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011: Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005). Seven studies focused more broadly on emotional distress (Allard 2007; Allen 2002;Bailey 2004; Chambers 2014; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2005). Finally, three interventions aimed to alleviate uncertainty resulting from diagnosis of, and treatment for, cancer (Bailey 2004; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005).

With regards to symptoms with a physical element, nine studies measured the impact of interventions on fatigue (Badger 2005; Badger 2013b; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Ream 2015; Yates 2005), six on cancer‐related pain (Barsevick 2010; Kroenke 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011: Thomas 2012), three on sexuallly‐related symptoms (Chambers 2015; Reese 2014; Reese 2018), and two on dyspnoea (Mosher 2016; Porter 2011).

Ten studies measured general symptom experience and reported overall symptom intensity and/or symptom distress (Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Barsevick 2010; Kroenke 2010; Mishel 2002; Molassiotis 2009; Porter 2011Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Traeger 2015).

Many symptoms were incorporated as secondary outcomes across studies. For example, a study evaluating a telephone‐delivered intervention for fatigue may also have incorporated anxiety and/or depressive symptoms as secondary outcomes.

Intervention format

A summary of intervention characteristics is provided in the table titled Characteristics of included studies. All interventions were delivered primarily by telephone to participants in their homes. However, only ten were delivered solely by telephone (Allard 2007; Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Bailey 2004; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Livingston 2010; Reese 2014; Traeger 2015).

Sixteen of the remaining study interventions were delivered by telephone in combination with printed materials and/or online/digital materials (Badger 2013a; Badr 2015; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Girgis 2009; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Watson 2017).

Two studies combined telephone calls with face‐to‐face sessions (Molassiotis 2009; Sherwood 2005), and three combined telephone calls with both face‐to‐face sessions and digital/printed materials (Allen 2002; Rawl 2002; Yates 2005). One final study evaluated an intervention that incorporated automated symptom monitoring and prescribing recommendations (regarding depressive symptoms and fatigue) made to participants by oncologists, in addition to telephone calls (Kroenke 2010).

Health professionals delivering interventions

Most interventions (n = 24) were delivered by nurses (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005; Molassiotis 2009; Porter 2011, Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005), including:

oncology nurses (Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005);

research nurses (Allen 2002; Barsevick 2004); and

psychiatric nurses (Badger 2005; Badger 2007).

Eight studies did not specify the specialty or training of nurses who delivered the interventions (Allard 2007; Bailey 2004; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Kroenke 2010; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005; Molassiotis 2009; Porter 2011). In nine studies, the nurses had received training in other skills necessary for intervention delivery, including counselling (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Barsevick 2004; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Ream 2015), communication (Chambers 2015), and education (Kroenke 2010).

In nine studies, interventions were delivered by professionals other than nurses. These included psychologists (Chambers 2014; Dong 2018; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Watson 2017), social workers (Badger 2013a; Mosher 2016), a mental health counsellor (Badr 2015), and master's prepared social workers and para‐professionals/psychologists/counsellors (Badger 2013b).

Theoretical basis of interventions

Twenty‐one studies used theoretical models to inform the telephone intervention: Self‐Regulation Theory (Allard 2007; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015), Interpersonal Therapy (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a), the Stress Process Model (Badger 2013b), the Common Sense Model of Illness (Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010), the Transtheoretical Model (Thomas 2012), Self‐Determination Theory (Badr 2015), Cognitive‐Behavioural Theory/Coping Skills Training (Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Porter 2011; Sherwood 2005), the PRECEDE Model of Health Behaviour (Yates 2005), Social Cognitive Theory (Mosher 2016), the Theory of Uncertainty in Illness (Bailey 2004; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005), and the Cognitive‐Behavioural and Sex Therapy Theory (Reese 2014; Reese 2018).

The theoretical basis informing the design of the interventions was unclear ‐ or unreported ‐ in 11 studies (Allen 2002; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Sikorskii 2007; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017). Although Allen 2002 did not specify the theoretical basis for the intervention provided, the intervention model for this study was based around problem‐solving and made use of motivational techniques in its delivery. Finally, Sikorskii 2007 employed a multi‐dimensional interactive approach, which drew on various strategies around coping, re‐framing, providing education, and eliciting support for adapting to, or overcoming, cancer‐related symptoms.

Number of calls/duration/timing

Most (n = 29) of the interventions provided a standardised number of telephone calls to participants; these ranged from one call in Chambers 2014 to 18 calls delivered weekly over 18 weeks in Molassiotis 2009. In the remaining three studies, the number of calls provided varied by need (Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Watson 2017), or the numbers of calls and the intervals between them were unclear (Girgis 2009).

Although most (n = 17) intervention calls were delivered weekly, three interventions were delivered every other week (Allen 2002; Rawl 2002; Thomas 2012). One intervention delivered three calls over three successive cycles of chemotherapy (Ream 2015), one provided four calls over two successive cycles of chemotherapy (Traeger 2015), and seven others provided a series of calls with increasing time intervals between them (Chambers 2015; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Porter 2011; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007). In one study, calls were made over a three‐month period at participants' convenience (Downe‐Wamboldt 2007), and in another, up to eight calls were again scheduled over an approximate 12‐week period (Watson 2017). Finally, Chambers 2014 made five calls but did not specify the timing of these calls.

Most frequently, the intervention comprised three or four calls (Allen 2002; Badger 2013a; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2005; Mosher 2016; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Sherwood 2005; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017). In three studies, participants received more than 10 calls: Porter 2011 delivered 14; Molassiotis 2009 provided 18; and although Kroenke 2010 planned to deliver four calls, automated symptom reports with high symptom scores triggered extra calls ‐ participants received on average 11 calls.

Twenty‐two studies reported the duration of calls provided (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005); duration ranged on average from 10 minutes in Yates 2005 to 70 minutes in Reese 2018.

Recording and documentation of calls

Only 15 studies recorded telephone calls in some way for quality assurance (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Livingston 2010; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011, Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Sherwood 2005; Traeger 2015). Downe‐Wamboldt 2007 assessed fidelity by reviewing the interventionist's notes to determine goals recorded and degree of problem‐solving achieved. Watson 2017 addressed fidelity by observing some of the intervention sessions.

Telephone calls were additionally documented in some way as part of the intervention (not explicitly for quality purposes): two used patient‐completed worksheets completed after calls (Allen 2002; Badger 2007); four obtained feedback surveys/documentation completed on a computer or via a touchpad telephone (Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Sikorskii 2007); one reviewed and assigned homework during intervention calls (Badr 2015); another required the nurse delivering the intervention to keep a diary recording participants' engagement with calls (Ream 2015); and two used patient diaries completed between telephone calls to help tailor the intervention (Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010).

Excluded studies

In the Characteristics of excluded studies table, we list the 45 studies excluded after assessment of full text (according to the criteria specified at Types of interventions) and specify the reasons for exclusion.

We excluded studies primarily because:

they did not address management of symptoms (n = 21); or

interventions were not delivered primarily by telephone (n = 12).

Risk of bias in included studies

Assessments of risk of bias and methodological certainty are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table and the Risk of bias graph (Figure 1).

Here we summarise risk of bias.

Adequate sequence generation: fulfilled in 22 studies (Allard 2007; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2005; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011 Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005).

Allocation concealment: fulfilled in 10 studies (Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Molassiotis 2009; Porter 2011; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005).

Blinding: fulfilled in six studies (Kroenke 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Sherwood 2005).

Incomplete outcome data assessed: fulfilled in 17 studies (Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2005; Molassiotis 2009; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005).

Free of selective reporting: fulfilled in 30 studies (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Chambers 2014; Chambers 2015; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Reese 2018; Sherwood 2005; Sikorskii 2007; Thomas 2012; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005).

Other bias: detected in 12 studies (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Chambers 2014; Dong 2018; Mishel 2005; Porter 2011; Ream 2015; Reese 2014; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Findings by symptom

1.1 Anxiety; telephone intervention versus control

Sixteen studies measured effects of their interventions on anxiety (Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Dong 2018; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005). These studies used several different validated scales.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Ream 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005).

State version of the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (Badger 2013b; Rawl 2002).

Trait Anxiety version of the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) ( Porter 2011).

Anxiety subscale of the Profile of Mood States ‐ Short Form (Bailey 2004).

Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA) (Chinese version) (Dong 2018).

Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) (Chinese version) (Dong 2018).

Investigator‐designed instrument composed of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), the Short Form‐12 (SF‐12) Scale, and the Index of Clinical Stress (ICS) (Badger 2007).

6‐item Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System short form anxiety measure (Badr 2015).

2‐item Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD‐2) Scale (Traeger 2015); 7‐item Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD‐7) Scale (Mosher 2016; Reese 2018).

In nine studies, anxiety was a primary outcome (Badger 2007; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Watson 2017). Two of these (Badger 2007; Badr 2015), plus three studies in which anxiety was a secondary outcome (Bailey 2004; Dong 2018; Ream 2015), provided data from 277 participants that reported change scores and associated standard deviations ‐ or these could be calculated. Dong 2018 measured anxiety outcomes with two measures (HAMA and SAS); only those related to SAS are displayed on the forest plot. This decision was based on the allied Self‐Rating Depression Scale, which was used to power the study. Three individual studies appeared to suggest that use of a telephone had a significant impact on symptom management of anxiety in participants with various types of cancer (Badger 2007; Badr 2015; Dong 2018), but another two trials found no evidence of a difference (Bailey 2004; Ream 2015). We did not pool the overall effect estimates due to considerable heterogeneity, but we have depicted results of individual trials in the forest plot in Analysis 1.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Symptoms, Outcome 1: Anxiety

It is interesting to note that Dong 2018, a three‐arm trial incorporating a telephone support arm in addition to telephone‐delivered reminiscence therapy and usual care control, determined that generic telephone support generated similar improvements in anxiety as telephone‐based reminiscence therapy.

Of the trials that did not report a magnitude of effect explicitly nor address baseline imbalance using change scores (or these and their associated standard deviations could not be calculated) ‐ and in which anxiety was a primary outcome ‐ three reported some effect on anxiety. Badger 2013b tested two different forms of telephone‐delivered intervention without usual care control. Although the study determined that interventions were associated with statistically significant decreases in anxiety, without a control group for comparison it is difficult to conclude that these improvements were generated by the intervention rather than by an alternative factor (including passage of time). Watson 2017 also had no control group, but this was an equivalence trial ‐ researchers were seeking to determine equivalence between standard and telephone‐delivered cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) in people with high psychological needs; conventional CBT has established efficacy. Watson 2017 determined that with regards to anxiety, telephone‐delivered and face‐to‐face CBT approaches were equally effective. Finally, Rawl 2002, in the trial report, noted improvements in anxiety nearing statistical significance (P = 0.09). The other four studies did not detect any significant intervention effect (Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011).

1.2 Depressive symptoms; telephone intervention versus control

Twenty‐one studies measured effects of interventions on symptoms of depression (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Girgis 2009; Kroenke 2010; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Rawl 2002; Ream 2015; Reese 2018; Traeger 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005).

The following validated measurement scales were used to measure depressive symptoms.

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badger 2013a; Badger 2013b; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Rawl 2002).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Ream 2015; Watson 2017; Yates 2005).

Profile of Mood States ‐ Short Form (POMS‐SF) (Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010).

Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) (Chinese version) (Dong 2018).

Self‐Rating Depression Scale (SDS) (Chinese version) (Dong 2018).

Depression severity subscale of the 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) (Kroenke 2010).

Short Form‐12 (SF‐12) (Barsevick 2010).

Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL‐20) (Kroenke 2010).

Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐9) (Kroenke 2010; Mosher 2016; Reese 2018).

2‐item Patient Health Health Questionnaire (PHQ‐2) (Traeger 2015).

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Porter 2011).

6‐item Patient‐Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System short‐form depression measure (Badr 2015).

In all but six studies (Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Ream 2015; Traeger 2015; Yates 2005), depressive symptoms was the primary outcome. Nine studies, including 1059 participants, reported quantitative results such as change scores ‐ or data enabling these and their associated standard deviations to be calculated (Badger 2005; Badger 2007; Badr 2015; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Dong 2018; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Kroenke 2010; Ream 2015) (Analysis 1.2). Dong 2018 measured depressive symptom outcomes with two measures (HAMD and SDS); only those related to SDS were included in the forest plot. This decision was based on use of the SDS to power the study. Three of these studies had measured depression as a secondary outcome (Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010; Ream 2015). Four individual studies appeared to suggest that use of a telephone had significant impact on symptom management of depression among participants with various types of cancer (Badger 2007; Badr 2015; Dong 2018; Kroenke 2010); Downe‐Wamboldt 2007 was of borderline significance. Many trials were small and underpowered and did not report magnitude of effect. We did not pool the overall effect estimates due to considerable heterogeneity, but we have depicted the results of individual trials in the forest plot in Analysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Symptoms, Outcome 2: Depression

Of trials that did not report a magnitude of effect explicitly nor address baseline imbalance using change scores (or these and their associated standard deviations could not be calculated) ‐ and that had symptoms of depression as a primary outcome ‐ four reported some improvement in the intervention arm. Rawl 2002 measured the impact of a telephone‐delivered intervention on depressive symptoms in patients with newly diagnosed cancer. Researchers found that patients who received the intervention had significantly fewer depressive symptoms (P = 0.05) midway through the intervention when compared to those in the usual care group, although this was not maintained. One month post intervention, the difference was no longer statistically significant (P = 0.07). Porter 2011 detected reduced symptoms of depression in lung cancer patients following provision of both of their two telephone‐delivered interventions (coping skills training (CST) versus education/support) (B = ‐5.55, standard error = 0.28, P = 0.05). As with the intervention's effects on anxiety, levels of depressive symptoms dropped more for patients with stage I cancer given the education/support intervention, and more for patients with stage II‐III cancer given the CST intervention (B = ‐2.38, standard error = 2.86, P = 0.006). Badger 2013a and Badger 2013b reported statistically significant decreases in depressive symptoms over time associated with delivery of two forms of telephone‐delivered intervention. However, neither study incorporated a usual care control for comparison. Finally, Watson 2017, an equivalence trial comparing face‐to‐face and telephone‐delivered CBT, determined that the telephone‐delivered version generated a statistically significant reduction in depressive symptoms equivalent to that seen with CBT delivered in‐person.

Three studies whose primary outcome was reduced depressive symptoms found no significant reductions in these generated by the interventions (Girgis 2009; Livingston 2010; Mosher 2016).

1.3 Fatigue; telephone intervention versus control

Nine studies reported on effects of interventions on fatigue. Six evaluated interventions delivered specifically to reduce fatigue (Badger 2005; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Mosher 2016; Ream 2015; Yates 2005). Another three studies measured fatigue as a secondary outcome arising from the interventions (Badger 2013b; Bailey 2004; Molassiotis 2009).

Fatigue was measured using the following measurement tools.

Multi‐Dimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) (Badger 2005; Badger 2013b).

Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) (Ream 2015).

Fatigue Distress Scale (Ream 2015).

Schwartz Cancer Fatigue Scale (Barsevick 2004).

General Fatigue Scale (GFS) (Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010).

Profile of Mood States (POMS), fatigue subscale (Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010).

National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI‐CTC) ‐ single item (Molassiotis 2009).

Fatigue Symptom Inventory (Mosher 2016).

Six studies reported quantitative results including change scores ‐ or data enabling these and their associated standard deviations to be calculated (Badger 2005; Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2004; Barsevick 2010; Ream 2015; Yates 2005). All but Bailey 2004 incorporated fatigue as a primary outcome. Collectively, trial authors had attained data on 895 participants. Three of the individual studies appeared to suggest that use of the telephone had a significant impact on symptom management of fatigue for participants with various types of cancer (Badger 2005; Barsevick 2004; Yates 2005). Although the intervention evaluated by Ream 2015 in a feasibility trial did not significantly reduce overall (global) fatigue, study authors reported that it did generate significant reductions in distress caused by the symptom (P < 0.05). Other studies found no evidence of any differences between arms (Bailey 2004; Barsevick 2010). We did not pool the overall effect estimates due to considerable heterogeneity, but we have depicted the results of individual trials in the forest plot in Analysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Symptoms, Outcome 3: Fatigue

Molassiotis 2009 reported significant reductions in fatigue generated by a telephone‐delivered home care intervention delivered weekly over 18 weeks to people given a course of oral capecitabine. However, differences in comparison with the usual care control declined over time. Greatest improvement in fatigue was found from cycle 0 to 2 (P = 0.005); by the end of treatment, these benefits were no longer statistically significant (P = 0.93). Badger 2013a, which evaluated two forms of telephone‐delivered health education and counselling (without usual care control), reported statistically significant reductions in fatigue (P < 0.05) through telephone‐delivered interventions. However, the pilot study Mosher 2016 did not detect any statistically significant benefit of a telephone‐delivered intervention aimed at reducing a broad range of symptoms associated with lung cancer (one of which was fatigue).

1.4 Emotional distress; telephone intervention versus control

Seven studies investigated effects of interventions on emotional distress (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Bailey 2004; Chambers 2014; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Livingston 2010; Mishel 2005).

Definitions of emotional distress and tools used to measure it varied across studies. The following measurement tools were used.

Profile of Mood States (POMS) (Allard 2007; Bailey 2004; Mishel 2005).

Brief Symptom Inventory‐18 (BSI‐18) (Chambers 2014).

Medical Outcomes Study 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36), Mental Health Index subscale (Allen 2002).

Derogatis Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale ‐ Self‐Report (PAIS‐SR) (Downe‐Wamboldt 2007).

Rosebaum's Self‐Control Schedule (SCS) (Bailey 2004).

Investigator‐developed scale originally developed for breast cancer patients (Livingston 2010).

Five studies including 968 participants reported quantitative results including change scores ‐ or data enabling these and their associated standard deviations to be calculated (Allard 2007; Allen 2002; Bailey 2004; Downe‐Wamboldt 2007; Mishel 2005) (Analysis 1.4). None of these studies reached significance. We did not pool the overall effect estimates due to considerable heterogeneity, but we have depicted the results of individual trials in the forest plot in Analysis 1.4.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Symptoms, Outcome 4: Emotional distress

Livingston 2010 evaluated effects of two telephone interventions on emotional distress but provided insufficient data to enable calculation of change scores (and standard deviations). Study authors report that although both interventions appeared to reduce cancer‐specific distress, neither generated statistically significant improvements when compared with the control. Chambers 2014 determined that both study arms (single‐session oncology nurse‐delivered telephone intervention and five‐session psychologist‐delivered telephone intervention) were associated with decreased emotional distress. However, once again, lack of a 'no treatment' control group renders it impossible to conclude whether this resulted from the interventions over other factors such as passage of time.

1.5 Uncertainty; telephone intervention versus control

Three papers reported the impact of interventions on feelings of uncertainty in relation to a patient's illness (Bailey 2004; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005). All three based their interventions on the same theoretical framework ‐ Mishel's Uncertainty Theory ‐ and focused on reducing uncertainty through strategies such as cognitive re‐framing of threatening events and problem‐solving strategies. These papers did not report change scores, or it was impossible to calculate these alongside the standard deviation of the change score, and meta‐analysis was not possible.

Uncertainty was measured using the following instruments.

Mishel's Uncertainty in Illness Scale (Mishel 2002).

Self‐Control Scale ‐ Problem‐Solving and Cognitive Re‐framing subscales (Bailey 2004; Mishel 2002; Mishel 2005).

Growth Through Uncertainty Scale (GTUS) (Bailey 2004).

Confusion subscale of the Profile of Mood States ‐ Short Form (POMS‐SF) (Bailey 2004).

Bailey 2004 delivered a watchful waiting intervention by telephone to men with prostate cancer. Researchers detected no statistically significant differences between group overall scores for uncertainty management. However, the intervention group displayed a significant improvement on the 'New view of life' subscale compared to the usual care group (P = 0.02). Mishel 2002 also addressed uncertainty in men with prostate cancer; these investigators delivered two telephone‐delivered interventions to men following surgery for their disease. The interventions differed only in that one group had supplementary delivery of it to a close family member. Study authors reported significant improvements in uncertainty management (F[16,438] = 1.96; P = 0.01), cognitive re‐framing (F[4456] = 3.81; P = 0.005), and problem‐solving (F[4456] 2.40; P = 0.049) in both intervention groups when compared with the control group immediately following intervention delivery, but these differences were not maintained over time.

Later, Mishel 2005 evaluated an uncertainty intervention in long‐term breast cancer survivors and found a statistically significant difference for cognitive re‐framing (proxy for uncertainty management) (P = 0.01). Outcomes were more pronounced in African American women (P = 0.03) than in White women. Late outcomes (20 months) of the intervention were reported in the subsequent publication of Mishel 2005 by Gil 2006; these results confirmed that benefits generated by the intervention were maintained over time (F[1479] = 3.94; P < 0.05, d = 0.06, n2 = 0.008). Further, women in the intervention group reported decreased illness uncertainty, whereas there was no change for women in the control group from baseline to 20 months (Wilk's lambda F(1479) = 4.85; P < 0.03, d = 0.09, n2 = 0.010).

1.6 Pain; telephone intervention versus control

Six studies examined interventions to relieve cancer‐related pain (Barsevick 2010; Kroenke 2010; Molassiotis 2009; Mosher 2016Porter 2011; Thomas 2012). These trials did not report change scores, or it was impossible to calculate these alongside the standard deviation of the change score, and meta‐analysis was not possible. Researchers measured outcomes using the following tools.

Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Barsevick 2010; Kroenke 2010; Mosher 2016; Porter 2011; Thomas 2012).

Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI‐CTC) pain item (Molassiotis 2009).

Bodily Pain Scale from the Medical Outcomes Study 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) (Kroenke 2010).

Barriers Questionnaire (BQ) (Thomas 2012).