Abstract

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is experienced by one-third of women globally, yet few programs attempt to shift men’s IPV perpetration. Community mobilization is a potential strategy for reducing men’s IPV perpetration, but this has rarely been examined globally. We conducted a mixed-methods process evaluation alongside a trial testing community mobilization in peri-urban South Africa. We used in-depth interviews (n=114), participant observation (160 hours), and monitoring and evaluation data to assess program delivery. Qualitative data (verbatim transcripts and observation notes) were managed in Dedoose using thematic coding and quantitative data were descriptively analyzed using Stata13. We learned that outreach elements of community mobilization were implemented with high fidelity, but that critical reflection and local advocacy were difficult to achieve. The context of a peri-urban settlement (characterized by poor infrastructure, migrancy, low education, social marginalization, and high levels of violence) severely limited intervention delivery, as did lack of institutional support for staff and activist volunteers. That community mobilization was poorly implemented may explain null trial findings; in the larger trial, the intervention failed to measurably reduce men’s IPV perpetration. Designing community mobilization for resource-constrained settings may require additional financial, infrastructural, organizational, or political support to effectively engage community members and reduce IPV.

Keywords: process evaluation, community mobilization, intimate partner violence, sub-Saharan Africa, informal settlements

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for women across the globe, with recent evidence from low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) suggesting disproportionately higher costs to health and human development compared to resource-rich settings (Devries et al., 2013). While IPV prevalence in South Africa is similar to other LMIC settings (Devries et al., 2013), rates of intimate partner homicide are six times the global average (Abrahams, Mathews, Martin, Lombard, & Jewkes, 2013).

The IPV field has increasingly begun to recognize that violence is a preventable behavior, with new interventions showing promise in reducing women’s experience of IPV (Ellsberg et al., 2015). However, men’s perpetration of IPV has lagged behind in the empirical evidence, both in terms of a lack of studies testing prevention interventions among men and disappointing results from existing men’s prevention trials. On the one hand, there are promising signals that group-based training among young men can decrease men’s reported IPV perpetration (Jewkes et al., 2008; Verma et al., 2008), particularly if combined with economic livelihoods strengthening as in the Stepping Stones Creating Futures program (Gibbs, 2018). However, the SHARE trial found reduced victimization reported by women was not accompanied by similar declines in men’s reports of IPV perpetration (Wagman et al., 2015). The SASA! intervention in Uganda and Partnership Initiative in Cote d’Ivoire both found null intervention effects on men’s reported IPV perpetration (Abramsky et al., 2014; Hossain et al., 2014). Troublingly, there are virtually no proven programs that effectively reduce reported IPV perpetration among known male abusers (Arango, Morton, Gennari, Kiplesund, & Ellsberg, 2014).

To prevent IPV, programs must effectively target men who use violent behaviors or prevent other men from starting those behaviors in the first place. One promising method for reducing men’s perpetration of IPV is community mobilization, which often involves programmers working alongside local community members to raise awareness and collectively address health challenges. Community mobilization is one of several related threads of participatory health methods that draw on theories of critical pedagogy and social justice (Freire, 1970, 1973). Community mobilization interventions have addressed sexual violence (L. Glenn et al., 2018) and youth violence (Kim-Ju, Mark, Cohen, Garcia-Santiago, & Nguyen, 2008) in United States settings. However, in LMIC settings past community mobilization trials have tended to focus on outcomes such as maternal health (Muzyamba, Groot, Tomini, & Pavlova, 2017; Prost et al., 2013), sanitation (Waterkeyn & Cairncross, 2005), or HIV outcomes (Cornish, Priego-Hernandez, Campbell, Mburu, & McLean, 2014; Lippman et al., 2013).

In recent years, however, work around community mobilization for IPV prevention has begun to emerge. In India, a mobilization intervention for shifting gender norms and reducing violence against women experienced notable challenges to active engagement from community members (Jejeebhoy & Santhya, 2018). In South Africa, community mobilization in the form of the One Man Can program implemented by Sonke Gender Justice shown to improve HIV-related outcomes (Lippman et al., 2018), but the same approach was not effective in reducing men’s IPV perpetration in a rural setting (Pettifor et al., 2018). Few community mobilization models have been deployed in informal settlements in urban areas, a notable gap given that slums are among the fastest growing human dwellings globally (Lilford et al., 2017). One exception is an ongoing trial in informal settlements in India, where community mobilization was theorized as a way to reduce violence against women (Daruwalla et al., 2019).

In addition to testing interventions in robust trials, it is important to unpack how these programs are conceptualized, delivered and why they may succeed or fail to demonstrate effect on men’s IPV perpetration. Process evaluations, undertaken prospectively alongside a trial, can detail how complex interventions are implemented, potential mechanisms for impact, and how context shapes delivery (Moore et al., 2015). The aim of this paper is to explore the process of implementing an intervention developed by Sonke Gender Justice through longitudinal qualitative and ethnographic data.

Methods

Conceptual framework

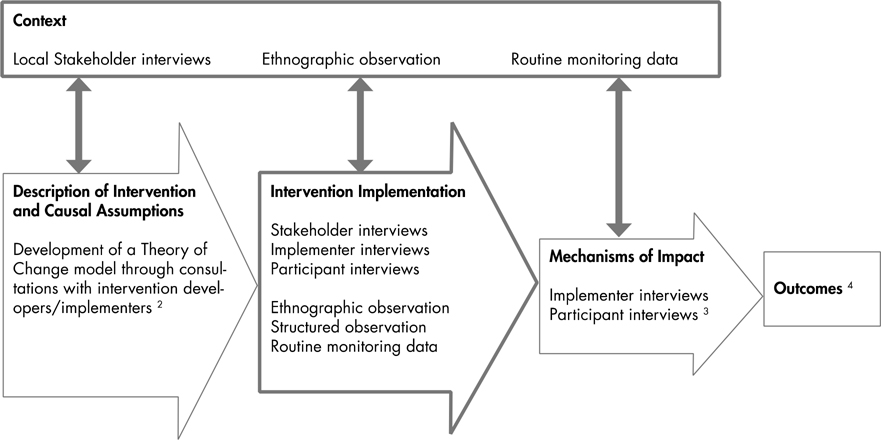

We used Moore et al.’s approach to process evaluations, which posits that intervention theory, context, delivery, and mechanism are essential components to understanding how a complex program works (Figure 1). In this paper, we prioritize intervention theory, program delivery, and trial context in order to explore questions around implementation: (1) to what extent was the intervention delivered as planned?, (2) how did local context influence its delivery?, and, (3) how strong a fit did intervention theory demonstrate in this setting? Figure 1 details our process evaluation approach and the methods of data collection used to answer these research questions.

Fig 1.

Process evaluation data collection 1

Notes

1 Adapted from Moore, et al. (2015) BMJ

2 Presented in Christofides, et al (2016) BMJ Open.

3 Developed in a separate manuscript

4 Presented in main trial findings paper, this journal (forthcoming)

Typically, process evaluations examine the extent to which an intervention was feasible to deliver and accessible to intended program recipients (Bonell, Oakley, Hargreaves, Strange, & Rees, 2006). They also tend to distinguish between inadequacy of the intervention plans (i.e. failure of theory) vs. challenges with delivering components as planned (i.e. implementation failure). In addition to intervention delivery, there is an increasing recognition of the role that context plays in trial outcomes (Pawson, Tilley, & Tilley, 1997). Descriptions of context help improve understanding of an intervention’s effectiveness, the findings of a study and data generalizability (Craig et al., 2008). Process evaluators should examine how context interacts with intervention mechanisms to produce intended outcomes (Bonell, Fletcher, Morton, Lorenc, & Moore, 2012). Context can also inform mid-level theory about how the intervention operates (Jamal et al., 2015).

Setting

The study was conducted in a semi-formal settlement, colloquially referred to as a ‘township,’ near Johannesburg, South Africa. We collected data in the township, which we have given the pseudonym Sweetriver, during the period of January 2016-August 2018. Sweetriver took form in the mid-1990s, when the fall of apartheid pass laws allowed non-whites to move closer to cities. The area is home to roughly half a million people (exact estimates are unknown as the most recent census, conducted in 2010, stated that there were 140,000 residents). There is a high numbers of migrants from other African countries, and internal migration – or people moving from other South African regions to this community – is among the highest in South Africa (Peberdy, Harrison, & Dinath, 2017). The setting is unequal compared to neighboring suburbs in terms of worse living conditions, higher degree of multi-dimensional poverty and lower levels of safety (Mushongera, Zikhali, & Ngwenya, 2017). Some live in multistory brick buildings that are electrified with running water, while others live in ‘shacks’ made of sheet metal and wood and use community taps and toilets located along dirt roads littered with garbage and open sewage. Throughout the neighborhood, even in more formal areas with paved roads and access to electricity, physical infrastructure is severely constrained. There are rarely open fields or recreational spaces outside of taverns. There is one community park and many neighborhoods lack buildings that can be used for group gatherings.

Intervention

The CHANGE intervention was designed by Sonke Gender Justice, a non-governmental organization that has worked in South Africa for the past 15 years. The CHANGE intervention was delivered by community mobilisers employed Sonke as well as volunteer activists who were recruited from participants in the intervention activities. There were a number activities planned, including: door-to-door discussion to raise issues of gender equality and human rights; providing workshops; painting murals and using these as a trigger for discussions; holding community dialogues; and, local advocacy efforts to demand service delivery from local government actors. A key element of the intervention was the workshops, which were held over two consecutive days during the week (two days of six hours) with lunch provided, chiefly facilitated by community mobilisers. There were six themes for the workshops, but they were not organized as a formal curriculum with an expectation that participants would attend all sessions, The six workshop themes were gender, gender socialization and gender roles; gender, power and violence (including an activity on communication skills and one on negotiation); gender, sexuality and sexual and reproductive health and rights, power and anger management; gender, violence and alcohol; gender, IPV and sexual violence; gender, the law, wellbeing and healthy relationships.

Data collection

We collected prospective process evaluation data alongside a cluster randomized control trial during the period of January 2016 through December 2018. The Sonke CHANGE Trial, described in full elsewhere (Christofides et al., 2018), was one of multiple rigorous evaluations in the What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Children consortium. We conducted a mixed-methods process evaluation in order to deepen our understanding of how the Sonke CHANGE intervention was implemented in practice and to help contextualize trial findings.

Qualitative data

Participant-observation was used to assess implementation ‘in real time’ and track changes in implementation over time. Structured participant-observation notes were collected by a member of the research team not involved in delivering the intervention. Structured observations sought to capture qualitative information about the quality of implementation, and to what extent the intervention activities were delivered according to the logic and hypothesis underpinning their design. In total, participant-observation was carried out during 160 observation hours over a period of 18 months, and included attendance at trainings, staff meetings, delivery of intervention components (workshops, dialogues, murals), and events with wider community stakeholders. Observation sheets completed by hand were transcribed into electronic form using Excel.

In-depth interviews using semi-structured interview guides were carried out with various stakeholders who had a unique perspective on the intervention, its delivery and effects (Figure 2). Interviewees were sampled based on their role in the project or intervention community, and interviews were conducted at baseline (early 2016), midline (during the course of 2017), and endline (early 2018). Purposive sampling aimed to reach a variety of participants according to age and gender. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with intervention managers, implementers, community stakeholders, and participants. One sub-set of participants of great importance to this particular intervention is that of volunteer activists. We over-sampled this group since they both participate in sessions and receive extra training to deliver some intervention components.

Fig 2.

Qualitative data collection

A topic guide was used that addressed issues of program plans, implementation, and community reception. Topic guides were developed using an iterative approach by the research team, with midline interview guides crafted after all baseline interviews were completed and preliminarily coded. A similar technique was used for endline interview guides, ensuring that input of participants guided additional interview topics. Interviewees were required to provide informed consent prior to the interview. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Quantitative data

We collected quantitative monitoring data using tablets and Open Data Kit software. At the time of completion of each intervention activity, staff or volunteers filled paper forms relating to the activity description, number of participants, and topics covered. For each two-day workshop and each four-hour mini-workshop, participants filled paper registers with their age and gender. To obtain a denominator of eligible men in each cluster, we conducted mapping walks of select clusters (n=2) and estimated household numbers based on aerial photos of other clusters. While this method is less precise than a household survey of all clusters, it was deemed appropriate given the lack of census data in this fast-growing township setting.

Data analysis

Qualitative data

Observational and interview data were imported into Dedoose, an online qualitative management tool. Thematic coding was conducted in phases by three researchers. The first phase consisted of the research team conducting open coding on three transcripts to generate a ‘start list’ of inductive codes. This list was reviewed by the research team and led to the creation of a codebook, which was applied to a sample of ten transcripts by two members of the coding team. Once consensus was reached on the meaning and intent of the coding framework, two researchers applied the codebook to chunks of text using a thematic approach. A process of iterative analysis enabled cross-checking of data sources to determine points of convergence and contradiction. We held a series of analytical meetings with the entire research team to assess saturation of data and identify emerging findings.

Quantitative data

Monitoring data were imported into Stata13 and analyzed using basic descriptive statistics (count, proportion, means). We calculated cluster saturation by calculating simple proportions of total number of men reached divided by total number of estimate men aged 18–49 years.

Results

Contextual factors

Several contextual factors framed the implementation of the intervention within the peri-urban township setting. These structural realities were observed across multiple forms of data collection, including in-depth interviews and participant observation. Here, we introduce salient contextual factors, several of which we return to in later sections of the Results in an effort to unpack how they altered program delivery.

Migrancy and sense of place

Most participants in interviews described how Sweetriver was made up of residents who had arrived from elsewhere, either as international or national migrants. Even among those who had lived in the area for a long time, the area seemed to lack a sense of belonging – instead it was described as a township where people “pass by” with “no investment”. Multiple respondents from participant and staff groups expressed a view that they would exit the township as soon as they had the means to do so:

“If I had money I would actually move out of this place. This place is not for human beings honestly. It is not a place to live in. I have had a very, very bad experience since I have moved in here.”

– Activist volunteer, baseline

There was an overall stigma around the community itself, causing residents to distance themselves from the neighborhood and make plans to leave:

“People don’t associate themselves as the community of Sweetriver. Immediately, if a person gets employment somewhere else, they will leave. They don’t want to see themselves staying here in Sweetriver because when you say to people you are from Sweetriver, it’s like you are from a horrible, horrible place.”

– Staff, endline

Multiple participants (staff and volunteer activists) explained that when a place does not feel like home, residents are less likely to care about making it better or about protecting their neighbors from harm. As one staff illustrated, it feels like residents think “it is not my home, I don’t care what is happening to whoever or to the police or the clinic.” This sensation is underscored by the fact that nearly all adults in Sweetriver arrived from somewhere else, given the township only started in 1995.

Social and structural marginalization

The township setting was defined by social marginalization in a number of ways. Most participants and staff spoke about poverty and crime being defining features of daily life, and several expressed distress by the lack of employment opportunities in the area. The lack of employment led to uncertainty about meeting basic needs, as well as a feeling of not achieving socially prescribed roles. For example, one staff recounted the types of families for whom unemployment and food insecurity caused major arguments about “providing”:

“If you are not working and there’s a stress that I’ve got - where will the next meal come from? - then maybe that is where the fight will start. Or maybe that [other] husband down the street, he’s doing good for his family and you, you are just sitting, you’re doing nothing. You are not a man enough because you are not working, you are not providing, you are not doing as other men are doing, then that’s where the fight will start.”

– Staff at endline

In many informal parts of Sweetriver people live in house shacks and closely aligned single rooms where space is severely limited. One community activist illustrated how her “home” was occupied by 14 different families:

“I live in a brick house, where there are 14 families. There are no bathrooms, we use our own houses, our own rooms to bath, to cook, do everything inside the room. We share the toilet, it is a pit hole outside. The house came with some bathrooms, but others occupy those bathrooms.”

– Activist volunteer at endline

Even amidst the physical closeness, respondents from management, staff, and participant groups reported a lack of social cohesion and a sense of separation in terms of psychic space:

“People say that back in the day people used to be these close-knit communities and if something happen to one household, the community would support them. And we don’t have that today cause you don’t know your neighbors. That’s why we see higher rates of crime and drug abuse and violence against women and violence in general.”

– Manager at baseline

Entrenched gender norms

Managers, staff, and participants aligned in describing the patriarchal gender norms underpinning relationships in this setting. In participant observation notes, workshop attendees would often describe the man as the “head of the household” and a woman’s place as being “in the home”. Women volunteers articulated the constraints placed on them by men who demand “respect” through homemaking and a lack of sexual autonomy:

Culture plays a role, you have to respect a man, whatever he is doing, you have to respect him and you must remain a woman under the man, so I think it is affecting a lot here in Sweetriver. You have to respect him, the man can have an affair but you are not allowed to have an affair. But you have to respect that. You have to take care of your home. Cooking, taking care of kids, you have to give back, when a man says I want a baby, you have to agree to that.

– Activist volunteer, endline

Another woman volunteer described her difficulties convincing her partner that working outside the home was appropriate for a woman: “He thought that if I go to work I will leave him and disrespect him, and he will be nothing to me.” In workshops, there were often homogenous views among participants about the roles of men and women in the household, with alternative views being expressed only in marginal ways:

One older man said that there should not be gender equality in the home, women must ask men for permission. A younger man agreed and said it was good to have multiple wives. Participants also felt that men should earn more because they do more. However, one participant suggested that it is okay for men to bring in the washing.

– Participant observation notes

Normative violence

Many participants living or working in the community described witnessing and being victims of crime. One staff explained that “violence in Sweetriver it’s like a norm now –you can be mugged, you can be robbed, and people just pass as if like they don’t see what is happening.” Indeed, of the 20 men interviewed at baseline, 5 had been held up at knife or gunpoint since moving to the township. One man reflects on the exasperation he felt coming upon a dead body on his early morning walk to work:

“You would see one dead body, then two or three. You sometimes see someone you know. It is tough when that happens. There was a man who worked as a traffic officer down there… when I woke up at 4am he would be going to work. He was an old man but he was also shot. I do not know what they wanted. They did not take his phone, they did not take his money. He had R1500 in his pocket.”

– Participant at baseline

In a context of high petty crime and persistent regularity of murder, community members often enacted mob justice. This, in itself, raised the normative levels of violence:

“Here in the informal settlement, the poverty is extremely high, so that’s where people tend to start looting. And when you’re looting they’ll give you a mob justice, that’s violence in itself you see, but people just hear you saying “vimba”, you see a person running, like running and then a person will be attacked without people asking what happened.”

– Staff at endline

One of the staff remembered a volunteer activist in the project explaining that he found out about robbers during the intervention door-to-door activities and later “went to that guy’s house, we beat him good…I have blood all over my clothes.”

With violence weaved into normal daily life, the project itself engaged with death on a regular basis, causing significant emotional trauma:

It’s actually really shocking that we’ve had study participants who have died, been murdered, we’ve had an activist volunteer who was killed. You know, it’s like life is really much more precarious, much more at risk.

– Manager at endline

Persistent hopelessness

The potent blend of poverty, marginalization, and lack of opportunity, when combined with frequent and persistent trauma, seemed to create a neighborhood that was on-edge and hopeless. There was certainly a sense of being left behind by services, and having no hope in society or their own opportunities:

With regards to crime, there’s a lot of hopelessness. You find a person, you’d be asking “why didn’t you call the police or report that?”, [and he would say] “no those guys will [only] be here after 4 hours, we’d have solved our problem by then.” A lot of people become resigned, especially those who are semi-skilled or unskilled, they become resigned to their situation. People often say, “people like us” as in “poor people like us can’t benefit.” A lot of people have actually lost all hope.”

– Staff at endline

As one manager described at endline, there is a strong sense that residents in the community “are no longer excited and looking forward to life; people have abandoned their dreams.”

Intervention delivery in light of contextual factors

We learned that while the total quantity of activities reached program goals, the quality of activities in terms of critical reflection and breadth sometimes fell short of expectations. In particular, the element of local advocacy was not implemented fully, and thus the level of community mobilization was muted. There were a number of contextual constraints that hampered implementation of the intervention. First, space constraints due to working in a peri-urban setting made it challenging to find adequate, safe locations for conducting the work. Material constraints around economic, food, and transportation needs of participants and staff framed implementation. Lastly gender attitudes made this particular community mobilization intervention challenging to deliver.

Physical space in a dense, impoverished context informed outreach strategies

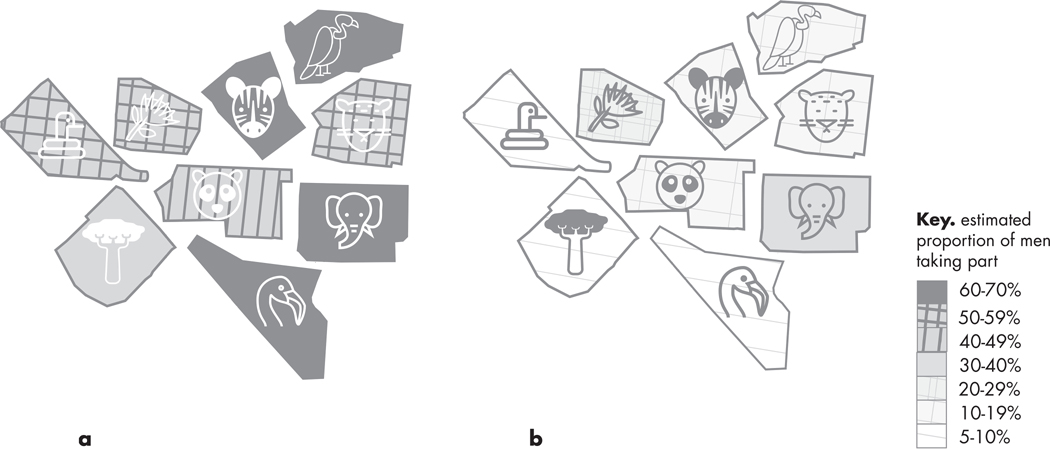

Outreach activities included information-giving sessions and door-to-door discussions with men and women in the community. Participant observation notes and monitoring data suggests these elements were delivered as planned, with high overall numbers: a total of 14, 878 people were reached with 1,103 hours of activity (of whom 8, 825 were men). In terms of saturation, the goal for intervention delivery was to reach at least 60% of men in each of the nine intervention clusters with at least one activity. This goal was met for four of nine clusters (Figure 3a), indicating that a majority of men in some clusters did receive at least one contact by program staff or volunteers.

Fig 3.

a. Saturation of all activities

b. Saturation of two-day workshops

Some outreach activities, however, were not delivered due to contextual constraints. Through participant observation, we learned there were no ‘digital stories’ delivered because these required a television to screen. The use of expensive equipment generated security concerns that precluded staff and volunteers to transport televisions to new areas of the neighborhood. Street soccer, previously a successful mode of bringing community members together in other settings, was not feasible due to the limited recreational space available in the township. Participant observation notes from staff meetings confirmed that the interest in these activities was curbed due to local constraints.

A similar safety challenge was experienced when trying to deliver activities called ‘open house’. In this activity friends, neighbors and family members were to invite one another to their homes to discuss any of the available project themes. People were reluctant to allow unknown local residents into their yards or homes. Participant observation notes showed this activity was tried for a week and then discontinued due to safety concerns around burglary or physical assault that open house hosts voiced to staff.

Challenges were also encountered in the delivery of workshops due to contextual factors. Several neighborhoods in the township lacked formal structures in which to hold workshops. At first, workshops were held primarily in taverns (as well as a small number of workshops in churches), but there were community members who felt unsafe or unwelcome in both. According to participant observation notes, women felt stigmatized if they were inside taverns during the daytime, and participants and other people in the taverns would drink during workshops. Participant observation notes from one tavern workshop illustrated:

The tavern very small and run-down. It was dark with no natural light. The room consisted of one pool table and seating around it. Men appeared more talkative than in the church workshop, but some younger men were drunk upon arrival.

– Participant observation

This excerpt highlights that young men, in particular, felt uncomfortable speaking up as they viewed churches as religious, female spaces.

These space challenges led to the adaptation of purchasing gazebos that could be constructed on short notice and hold up to 40 participants:

We’re using taverns to do the workshop, where it’s a challenge because some will tell you that they can’t feel safe to stay in tavern. And why we were looking at the taverns was that we were targeting men, so we thought to find women, this time let’s use a church. But some don’t feel comfortable to stay in the church. So now, we are using our gazebos.

– Volunteer activist at baseline

Another upside of the gazebos was their visibility for people walking by, and with the project name displayed prominently they served as a form of advertising intervention activities. Participant observation suggested this innovation was a successful way the project adapted to the local environment.

During workshops the ability of participants to engage deeply with issues of intimate partner violence was inhibited by the high level of neighborhood deprivation. One manager explained how the quality of discussions was limited by the fact that many participants were hungry and arrived only for the period of the workshop that provided food:

You can’t work in this community and be mechanical in how you do things and ignore what the situation is. Obviously then the workshops, the quality, the order and all of this, is compromised when people are poor, people are hungry, and the workshop is offering this opportunity for people to have food. And so people came to the workshop for food.

– Manager, endline

Several other contextual constraints impacted participation levels in outreach activities. Being employed or seeking employment precluded many from taking part in intervention activities that were typically conducted Thursdays and Fridays, during working hours. Participant observation notes suggested domestic responsibilities prevented full and meaningful participation in activities that lasted a full day, such as workshops and community dialogues. Some community members had limited capacity to engage due to language issues, particularly common in intervention clusters located in informal areas where migrants from outside of South Africa were more likely to reside.

Critical reflection amidst entrenched gender norms was a challenge

Beyond the outreach activities, program planners intended to reach participants with activities that stimulated critical reflection. An example of this was a two-day workshop with men and women that was framed by deep discussions around gender and power, lending the opportunity to reflect on social norms and reconsider new beliefs and actions. The saturation of workshops in most clusters was low, suggesting that only 8–33% (average 15%) of men in any given cluster had the opportunity to participate in an activity designed for critical reflection (Figure 3b). In total, 982 men (8%) took part in two-day workshops out of a total of an estimated 12,500 men of eligible age in the intervention areas. Most of the 982 men who took part in workshops only took part in one or two times. This means they were not exposed to full range of curriculum content and would therefore missed out of the cumulative insights of taking part in the whole range of workshops.

Critical reflection and “consciousness raising” (also called “conscientization”) seemed to be limited among participants due to the relative lack of deeper reflection during the two-day workshops. One manager explained that activities which occurred frequently, such as door-to-door visits to local homes, did not provide the type of opportunity required for true conscientization:

“I think that there is awareness raising, but I don’t really know whether conscientization has happened. Because conscientization is actually a much deeper process than simply having awareness raised … enormously deeper than door-to-door conversations are lasting maybe 20 minutes. I don’t think anyone’s reaching a level of conscientization in that period of time. I mean the workshop is the only space where I think there’s enough time for conscientization to truly happen.”

– Manager at endline

Critical reflection was further hindered by deeply entrenched gender norms that made many unemployed male participants feel resentful about women leading activities. Indeed, program delivery intended to model equitable gender roles by assigning one female and one male staff to each team of mobiliser (three teams in total). However, female staff described how “as soon as I stand in front of them, there will be nasty comments, chaos, they won’t listen.” A male staff member empathized and recounted how the tone of the workshop would shift as soon as he handed over to female colleagues:

I’d get a good response and the energy in that space would be good because I’m the one who’s leading and then my female co-facilitator will come and do the next activity, and the mood would start to change. You’ll see men going outside, smoking, starting to talk, do a little bit of chat…When my female colleague asks the very same question [as me] the men say, “No but I can’t respond to you because in my culture, I cannot listen to anything that comes from a woman.”

– Staff, endline

To avoid these awkward and unproductive circumstances, some female staff would allow the male to “take the lead” in order to align with neighborhood expectations about the appropriate roles for men and women in a public setting. However, participant observation notes confirmed that the disruptive comments served to divert focus away from the project messages and sometimes negatively influenced attitudes of other participants.

An important exception was the relatively impactful outcomes of critical consciousness among volunteer activists. Volunteers narrated experiences of how repeated exposure to intervention components, in particular workshops, facilitated a process of critical self-reflection regarding their own gendered behaviors and attitudes. This included some volunteers desisting from using violence against their intimate partners. Over time, a majority of activist volunteers began to take on new forms of social identities as ‘gender activists’ and to be passionate about the intervention’s success. Several female volunteer activists described a sense of empowerment and willingness to “stand up” rather than feel controlled by men:

[Sonke] has influenced me a lot. I used to think that I have to hide behind my fiance, and I had to hide behind men I had to be controlled by men. Since being here I know that I can do anything I put my mind to. Whatever I want to do, I can do it. I could just stand up and do whatever I want to do.

– Activist volunteer at endline

Volunteer activists began to engage in peer-education and activism of their own accord, outside of intervention activities. Participant observation notes suggest hhis included speaking with family members, friends, acquaintances and community members as well as encouraging peers to change. In this way, the reach of the intervention messages may have been diffused through interpersonal relations in everyday settings. One volunteer activist spoke about convincing his violent brother-in-law to drink less, which helped his sister’s relationship. Another described helping his mom process the abuse she used to experience at the hands of his father:

I realised that my mum was violated [and she needs to tell] somebody. I saw some men beating someone, my mum answered, “ja, all mens are dogs.” It is only the words that she could say. And she started crying and explaining she was beaten by my dad. That is why my mum and dad divorced, you see that it was violence, something like that.

– Activist volunteer at endline

The volunteer activist accompanied his mother to counseling and supported her to access help for her distress.

Material constraints framed mobilization potential

Volunteer activists were seen as a key element for diffusing the themes of the intervention to the broader community. The notion that community-embedded volunteers would take up the intervention approach was central to the theory of the project. Volunteer activists were recruited successfully from intervention clusters, with the inclusion criteria being: living in the neighborhood, and having an interest in the project. They attended brief training to orient them to the expectations of the role. Volunteer activists in in-depth interviews recounted various reasons for starting the role, including a desire to reduce gender inequality and personal experiences of IPV (common among female volunteers), a desire to uplift the community more generally (common among older male volunteers), and a desire for gainful employment (common among younger male volunteers).

The reach of mobilization by volunteer activists was constrained by the low number of activists recruited and the challenge of keeping them retained. There was a total of 56 volunteer activists recruited over the 2 years of intervention delivery, but a maximum of 18 were active at any one time point (Figure 4). Participant observation notes confirmed the relatively high turnover of volunteer activists and the struggles to keep a consistent group engaged in the outreach work.

Fig. 4.

Total number of ‘active’ volunteer activists per month of intervention delivery.Note: ‘active’ denotes the volunteer took part in one or more activities that were reported in routine monitoring data

There were multiple reasons reported for the high turnover of volunteer activists. One reason was the movement of activists in and out of the community and a low sense of community cohesion:

Retention rates for volunteer activists are very low, and I think that’s really directly related to the kind of places that we’re talking about and the kind of environment. People are mobile, they’re transients, it’s not a stable community. And it brings up questions around what is community exactly and what binds people together in different settings.

– Manager at midline

Another reason was that volunteer activists were unpaid. As volunteers they did received nominal reimbursement for transportation costs (roughly US $4 weekly). However, in a context of immense deprivation, this small token reimbursement was an enticement for some to take part and for some was more important than the intervention message:

You had volunteer activists who stayed because they knew they could get R60 (US $4). Now that’s a lot of money for somebody that doesn’t have anything. It means they can buy paraffin, they can buy candles, they can buy food to eat for a day or two. But also it also meant you’re not retaining volunteer activists for the right reasons. You are not retaining volunteer activists who had internalized these messages, who would champion these messages.

– Manager at endline

In addition to managers highlighting material deprivation, participants themselves spoke about their ingenuity in using the small transportation stipend strategically. One female participant carefully detailed how she could extend the small allowance to buy food for her family. In participant observation notes, volunteer activists stopped attending the activities the moment they obtained short-term work.

Although the strategy of using volunteer activists was strong theoretically, it proved practically difficult within this peri-urban setting. A manager expressed frustration when emphasizing that “volunteerism is much easier when people are not actually struggling with basic survival.” Another manager noted that to take ownership over the project, communities likely needed more concrete provision of basic services, including paying people for their time commitments:

I think any community mobilization model that does not address issues of deprivation in any way, will have serious challenges. If you go to design a community mobilization model that encourages some kind of ownership of the program by the communities, then you’d better think about what else are you going to offer them other than them just coming. Especially when you still have a legacy of the past where people are extremely caught up in inequalities, people are unemployed, people don’t have access to basic human right needs, like water, sanitation, proper shelter.

– Manager at endline

The high turnover of volunteers and the financial motivations that led some people to volunteer raised concerns among managers about the quality of delivery of intervention activities by volunteers:

I don’t know what happens in the conversation that a volunteer activists has with a community member - the extent to which that actually really resembles what was in the intervention manual, I don’t know how much it gets watered down, how much different pieces get picked up and focused on rather than others, whether links are made or not made. It’s such a great idea but I think it’s really, really challenging in reality to actually deliver the model, as it’s proposed.

– Manager at endline

The management questions around quality were contrasted by volunteer activists themselves, who felt that their efforts had visibly improved the community. One female activist volunteer explained how people would approach her in the street for advice about help-seeking after experiencing violence:

Ever since I joined Sonke I can see I can say Sonke is improving people’s lives. When we are going down the street you will meet so many people with many problems and then when we refer them some will help some will refer them to the office, some will refer to the social workers

– Activist volunteer, endline

A male volunteer described how he would warn neighbors that they would be arrested for violent behavior:

Since I joined Sonke, I have got a full experience, each and every thing. I even go and give pamphlets. I tell everyone, “I am going to report you because that thing you are doing is not good for me - someone is going to arrest you.”

– Activist volunteer, endline

Both quotes, however, highlights a punitive and reactive approach to violence prevention. Rather than working with family members and friends to curb the use of IPV in the first instance, several volunteer activists emphasized their ability to respond to violence after its use.

Institutional skills for local advocacy were limited

The local advocacy strategy was to engage in a high-profile media campaign that would highlight the issue of violence against women and hold local government actors to account regarding the ineffective tackling of IPV. Unlike the community outreach arm of the intervention, there was no manual to instruct staff and volunteer activists on how to undertake local advocacy activities. As a result, the project workplan did not include advocacy activities, but rather waited for an external ‘trigger event’. The lack of strategic focus on local advocacy was noted in participant observation notes during staff meetings, where goals were set for outreach but not for advocacy efforts. As one manager explained “mobilization is inherently ad-hoc, as it needs to be kind of organic to see what works.”

The ad-hoc approach to local advocacy led intervention staff to build coalitions with NGOs working in Sweetriver, which were either involved directly in responding to the needs of survivors of GBV or organizations indirectly involved in IPV prevention, e.g. mental health and drug dependency organizations. Coalition building was seen as essential for strengthening the legitimacy of intervention messaging, establishing IPV as a political priority in Sweetriver and amplifying the collective voice of partnering organizations.

The ad-hoc emphasis placed on coalition building inadvertently served as a constraint on the local advocacy strategy of government protest. During the course of the intervention an opportunity arose to engage in a high-profile media campaign, which would have highlighted the ineffectiveness of the justice system and other state bodies to prevent IPV. Undertaking such a campaign would have led intervention staff publicly criticizing the police and government officials. However, participant observation and in-depth interviews highlighted a potential risk that public criticism of the police may have hindered coalition partner work in the neighborhood. Ultimately, the high-profile media campaign was considered too risky for institutional partners and forgone.

Instead a more ‘insider approach’ was developed of establishing a community body called the “Gender Based Violence Forum”. Participant observation notes showed that the forum drew together coalition partners to jointly advance IPV as a political priority through regular meetings and a collective presence in the neighborhood. However, this entity was established during the closing phases of the intervention and did not influence community structures during the intervention’s timeline.

Ultimately, intervention staff were not in a strong position to undertake this form of local advocacy, as reflected by a manager:

To be truthful, focus at local government level, I haven’t seen it a lot. At Sonke, we are very good at, upstream, like government policies. So when it came to, “what are the by-laws in that particular area that we can use to do advocacy?”, we didn’t analyse this type of things. I think it was because of the lack of knowledge. So we were supposed to build a local government manual but we didn’t realize we need to have a plan for this particular thing. So local government level advocacy didn’t happen.

– Manager at endline

Intervention staff and volunteers only received specific training on engaging in local advocacy in the last phase of the project. The lack of local advocacy training was highlighted by one ground-level staff, who recalled the inability to give guidance to his staff around police engagement: “they ask how to access the police and we have been trying to go to the police, we’ve been trying to do this but we are not winning.” Another staff member yearned for more training around activism and legal frameworks for understanding gender and violence:

I would like to know about gender activism more. This is a start for me so if there’s more training to do that, then that would be very good. And maybe some training for the whole team on different laws and legislations and stuff because sometimes a person would actually ask you about a law or a legislation and then I would be able to answer or give a clue.

– Staff at midline

Other local advocacy was undertaken in relation to disseminating the results of the baseline study findings in local and national media. For example, the baseline findings of high rates of IPV were shared with two local newspapers and led to multiple instances of radio coverage. However, this local advocacy had the unintended consequence of leading to backlash among community members. There were threats made to staff and several neighbors visited the intervention office to formally complain. The threat of violence led to intervention activities to be suspended for a short period of time. Among intervention and research staff who have been working in the field of IPV this was an unprecedented response. It highlighted how the attempts to reduce IPV in peri-urban communities can provoke violent reprisals for intervention staff.

Training of staff laid groundwork for workshops, but volunteer activists needed more support Staff received intensive training around the workshop curriculum and facilitation skills, many sessions of which were accompanied by participant observation notes. This seemed to lay the groundwork for their ability to engage with groups and deliver intervention messages:

The training that I’ve received is how to facilitate, how to mobilize, how to engage, how to interact with people, your attitude towards the participants because those people, they’re not going to be knowing what is that that we’re doing so should have time for them, be patient with them. I’ve learnt a lot, I’ve been exposed to things like I wasn’t aware of them.

– Staff at baseline

However, there was limited supervision capacity around some of the more sophisticated skills required for managing groups, such as leading difficult conversations, or inviting people to dive into “hot topics” that are emotionally charged. This dynamic was compounded by the contextual reality that a high proportion of participants at any given workshop were likely to have current anxiety symptoms, a history of abuse, food insecurity, or similar traumatic experience. In one particularly potent example of this in a group setting, participant observation notes detailed a fraught discussion by a small number of men that positioned males as also being victims and receiving insufficient attention. A statement of “what about us men?” was used at multiple workshops as a defensive, hijacking technique – positing that since people other than women and children had hardships, violence against women was not the correct topic to discuss.

The skills developed among activist volunteers seemed insufficient to support their own leading of activities. Throughout the entire intervention, a paid staff member would typically lead each activity, rather than handing off responsibility to an activist volunteer as was intended:

Some people feel really passionately about issues and about wanting to make a difference to the community. And those [volunteer activists] may be more inclined to stay. Others may not feel the same depth of passion and engagement and so, once their immediate needs were met, they lost interest…My understanding was that volunteer activists would run workshops, like shorter workshops, but that never happened. They do door to door, so they talk to people one-on-one or small group but they don’t ever run a formal workshop which was surprising to me because that wasn’t how I understood the intervention to be designed.

– Manager at endline

The skills among activist volunteers were unequal, since the only prerequisite for starting the role was interest in the project. The pool of available “applicants” for a volunteer activist role was somewhat limited by the fact that they needed to reside in the intervention community itself and be able to volunteer between Monday to Friday, from 9am to 5pm. Participant observation notes showed that the people interested were unemployed and some lacked formal education. As a manager described, this lack of basic skills made the training environment challenging since, “if all I have here is people who have high school education, it takes longer to train them.”

Discussion

We found that a community mobilization approach to reducing men’s IPV perpetration in a South African township setting was feasible to deliver, but was constrained by contextual challenges. The Sonke CHANGE intervention had a number of programmatic successes, including marked personal change among staff and activist volunteers, high visibility of the intervention in the township setting, and good delivery of outreach activities to a large number of local participants. There were also a number of implementation challenges. The element of local advocacy did not receive institutional support and staff training required to implement it. Aspects of mobilization were weak, inhibited in part by insufficient skills and numbers of staff and volunteers.

Contextual challenges

The social context of a peri-urban settlement framed intervention delivery. Engaging communities in discussions around masculinity, partnership dynamics, alcohol use, mental health, and violence against women is difficult work in most settings. This was further compounded by the precarious and unsafe living conditions of this particular project, which led to feelings of mistrust and suspicion of “others” from different national and ethnic backgrounds. Even the definition of “community” in a setting where people do not consider themselves to be “home”, and where they view themselves as separate and distinct from others living close by, poses a challenge for mobilization (Minkler, 2004). Indeed, the criminology field has long embraced the notion that social cohesion and collective efficacy are important pre-conditions for reducing levels of neighborhood violence (Sampson, 2006). In this particular instance, social cohesion seemed limited, and was markedly lower than the rural areas where the intervention had had greater success previously (Pettifor et al., 2018). It is plausible that community mobilization within spaces that lack social cohesion may need to be theorized in a new manner, perhaps with greater emphasis on community building and a longer time-frame to develop trust and skills (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998).

There were notable constraints around infrastructure and poverty, many of which project staff navigated in creative ways. Yet, it may not be feasible to ask local participants to mobilize around “higher-order” topics like gender and violence when basic necessities of food and shelter are unaddressed. These crucial aspects of working in a peri-urban settlement were not considered adequately prior to adapting the intervention to the study setting, even though community assessment is seen as a critical step for community mobilization work (Lily Glenn et al., 2018). This adaptation oversite may be partly explained by the history of the intervention, which had been implemented successfully for a number of years in an impoverished rural setting (Pettifor et al., 2018). There was a reasonable expectation that learnings from the rural setting could be transferred to the peri-urban setting. In reality, many of the community dynamics were different, especially related to trust and cohesion. Moreover, the feedback loop between staff “on the ground” in the peri-urban setting and management at the organisation was not sufficiently developed to enable substantial modifications or adaptations to be made rapidly during the implementation period.

Insight on trial results

These process evaluation findings add texture to the main trial results suggesting that the intervention had no effect on men’s perpetration of IPV (Christofides et al., in press). Even still, exposure to the intervention did lead to personal transformation and critical consciousness among staff and volunteer activists. This group was consistently working with the intervention material and reflecting on their own lives, resulting in individual behavior change and small, but important, acts of community activism. Nevertheless, this was a relatively small group (61 men and women in total), and changes in these community members would be unlikely to influence levels of IPV use across entire neighborhoods. Indeed, the total number of participants reached (n=14,000) was considerably lower than similar IPV prevention and gender norms trials in Uganda and Rwanda (Abramsky et al., 2016; Stern & Nyiratunga, 2017). Additionally, volunteers had passion and commitment for the project but often lacked the skills and self-confidence required for transforming entrenched community norms – a challenge recognized in programs elsewhere (Jejeebhoy & Santhya, 2018).

This finding underscores the ambitious nature of our trial design. We measured the changes in intervention neighborhoods after 18 months of exposure to the intervention. We anticipated that “normal” community members would change their violence behaviors, whether they actually took part or not in intervention activities. While this aligns on paper with how Sonke positions their community mobilization work, it may be challenging to implement in practice. Indeed, many scholars cite that community programs lack adequate time to develop deep relationships within community (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Further compounding the interpretive challenges of these data is the fact that some scholars would consider the use of randomized control trials inappropriate to measure social change over time (Victora, Habicht, & Bryce, 2004).

We learned that although IPV awareness and knowledge can increase through an intervention such as this, deeper critical reflection and diffusion of messages may be challenging. Critical reflection among participants may have been hindered by an oversight in the design of the intervention manual, which was predominately written from the perspective of men and put limited emphasis on a woman’s perspectives. For example, the intervention manual provides no activities focusing on the emotions or needs of violence survivors.

Lessons for program and theory

The lessons from the process evaluation, coupled with findings from the trial, suggest that brief outreach as a form of community mobilization may not be sufficient to change deeply entrenched gender norms and behaviors. Not only were implementation aspects problematic, but key theoretical assumptions of this community mobilization project deserve additional attention. The Sonke work was theorized in advance of starting work in Sweetriver. Yet, as Lily Glenn et al. note, mobilization projects should “critically consider whether to even attempt to “mobilize” a community that was not involved in the conceptualization of the initiative,” (2018). It is also challenging to work only with a small, marginalized group and expect this will ultimately shift power relations between disadvantaged groups and the larger society (Sorensen, Emmons, Hunt, & Johnston, 1998).

Another theoretical mismatch is that Sonke conceptualized mobilization to be led by community members themselves – as a way to ensure strong local buy-in throughout – yet these staff and volunteers sometimes lacked the skills to deliver sophisticated sessions on gender. Our team and others have noted that brief trainings often fail to provide the sustained intellectual, strategic, or material resources required for successful mobilization efforts (Hatcher et al., 2011; Visser & Schoeman, 2004). Organizations hoping to do this work going forward will need to provide training, supervision, and an ongoing reflective space for local volunteer activists (Gram, Daruwalla, & Osrin, 2019; Jejeebhoy & Santhya, 2018; Stern & Nyiratunga, 2017).

Community mobilization often asks volunteers to raise the consciousness of fellow neighbors and friends, yet critical questions must be raised as to whether this is ethical, safe, or appropriate in a setting where there are high rates of violence. A major constraint to active participation in the mobilization efforts of this intervention was the material needs of participants. For example, those attending workshops while hungry were more interested in obtaining the free lunch than, perhaps, engaging in workshop topic. Similarly, the composition of activist volunteers turned over rapidly as these residents left the group to seek employment opportunities. As Gram et al. advise, “we cannot expect individuals taking volunteer time from their overburdened lives to have all the answers to the manifold problems of mobilizing, organizing and delivering effective action.”

Designing community mobilization for resource-constrained settings may require new strategies. For example, the addition of financial services for participants may improve their ability to take part in programming, as was the case for the Indashyikirwa mobilization project in Rwanda that incorporated village savings groups into IPV prevention (Stern & Nyiratunga, 2017). For activist volunteers in situations of extreme poverty, it may be helpful to offer material incentives to encourage sustained participation (Gram et al., 2018), though this has been seen by some scholars as resulting in tokenistic action (Cornwall, 2008).

Longer-term investments in community infrastructure, in the form of buildings and soccer fields, could help create the space and goodwill for this type of intervention. If, for example, local government were targeted with strategic advocacy efforts, larger community-level change may have become a possibility. Certainly, Sonke aims to employ political advocacy for IPV prevention (Peacock & Barker, 2014), yet despite this institutional knowledge, local advocacy did not materialize during our trial in the peri-urban setting. There is a notable tension for civil society organizations to both deliver essential services and to hold the state to account through protest. It is possible that local advocacy may need to take new forms, such as coalition building with other organizations (which was done successfully) and working alongside government to obtain new resources.

Limitations

The data presented here has been analyzed in light of the main trial findings, which allows for a post-hoc interpretation of trial results through the qualitative data (Moore et al., 2015). While this precluded our ability to prospectively assess the intervention, we documented process evaluations at various time points alongside intervention delivery. This structured step helped the team generate hypotheses about how the intervention was delivered and how variability in trial outcomes might emerge. Monitoring data may double-count participants, since it was based on total numbers attending each activity rather than by asking for participant names or identification numbers. Qualitative data analysis harnessed the views of multiple coders, but we did not conduct formal tests of inter-rater reliability. Instead, we aimed to achieve interpretative consensus through analytical meetings throughout the coding and write-up. Including authors from the implementing agency has limitations, in that organizational views may take priority over critiquing program delivery. However, we developed a strong academic-organizational partnership over several years that helped both researchers and programmers critically reflect on the findings and program approach in a constructive manner. Engaging together in the writing process strengthened the contextualization of results and the ability of Sonke as an organization to learn from the research findings.

Conclusions

In peri-urban South Africa, we learned that community mobilization could be implemented with high fidelity with regards to outreach activities, but was more challenging to deliver in terms of critical reflection and local advocacy. While community mobilization is a laudable intervention goal in theory, its application in practice has notable challenges, particularly in an under-resourced urban setting. New empirical work can help identify which elements of community mobilization hold promise in varied contexts, and programs should prioritize local community voices in preparation and adaptation phases. The goal of reducing men’s IPV perpetration through community mobilization may be achievable, but it will require longer timeframes and more context-specific strategies than were achievable during this trial.

Highlights.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is experienced by one-third of women globally, yet few programs attempt to shift men’s IPV perpetration.

We assessed community mobilization for IPV prevention through 114 interviews, participant observation of 160 hours, and monitoring and evaluation data.

In an under-resourced setting where many residents felt afraid, overwhelmed by poverty, and disconnected from fellow neighbors, community mobilization was difficult to achieve.

Outreach and increasing knowledge around IPV is an attainable program goal, but extra financial, infrastructure, and mentorship support is required for community mobilization.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the fieldwork team and facilitators involved in the study, as well as the participants for sharing their data.

Funding: This trial is funded through the What Works To Prevent Violence? A Global Programme on Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) funded by the UK Government’s Department for International Development (DFID). However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the department’s official policies and the funders had no role in study design, collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

References

- Abrahams N, Mathews S, Martin LJ, Lombard C, & Jewkes R (2013). Intimate partner femicide in South Africa in 1999 and 2009. PLoS Medicine, 10(4), e1001412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramsky T, Devries K, Kiss L, Nakuti J, Kyegombe N, Starmann E, … Watts C (2014). Findings from the SASA! Study: a cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Med, 12(1), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abramsky T, Devries KM, Michau L, Nakuti J, Musuya T, Kyegombe N, & Watts C (2016). The impact of SASA!, a community mobilisation intervention, on women’s experiences of intimate partner violence: secondary findings from a cluster randomised trial in Kampala, Uganda. J Epidemiol Community Health, 70(8), 818–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, & Ellsberg M (2014). Interventions to prevent or reduce violence against women and girls: A systematic review of reviews. [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Fletcher A, Morton M, Lorenc T, & Moore L (2012). Realist randomised controlled trials: a new approach to evaluating complex public health interventions. Soc Sci Med, 75(12), 2299–2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell C, Oakley A, Hargreaves J, Strange V, & Rees R (2006). Assessment of generalisability in trials of health interventions: suggested framework and systematic review. British Medical Journal, 333(7563), 346–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofides N, Hatcher AM, Pino A, Rebombo D, McBride RS, Anderson A, & Peacock D (2018). A cluster randomized controlled trial to determine the effect of community mobilization and advocacy on men’s use of violence in peri-urban South Africa: Study protocol. BMJ Open, 8, e017579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish F, Priego-Hernandez J, Campbell C, Mburu G, & McLean S (2014). The impact of community mobilisation on HIV prevention in middle and low income countries: a systematic review and critique. AIDS Behav, 18(11), 2110–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall A (2008). Unpacking ‘Participation’: models, meanings and practices. Community development journal, 43(3), 269–283. [Google Scholar]

- Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, & Medical Research Council G (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daruwalla N, Jaswal S, Fernandes P, Pinto P, Hate K, Ambavkar G, … Osrin D (2019). A theory of change for community interventions to prevent domestic violence against women and girls in Mumbai, India. Wellcome Open Research, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries KM, Mak JY, Garcia-Moreno C, Petzold M, Child JC, Falder G, … Watts CH (2013). The global prevalence of intimate partner violence against women. Science, 340(6140), 1527–1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsberg M, Arango DJ, Morton M, Gennari F, Kiplesund S, Contreras M, & Watts C (2015). Prevention of violence against women and girls: what does the evidence say? Lancet, 385(9977), 1555–1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn L, Fidler L, O’Connor M, Haviland M, Fry D, Pollak T, & Frye V (2018). Retrospective evaluation of Project Envision: A community mobilization pilot program to prevent sexual violence in New York City. Eval Program Plann, 66, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn L, Fidler L, O’Connor M, Haviland M, Fry D, Pollak T, & Frye V (2018). Retrospective evaluation of Project Envision: A community mobilization pilot program to prevent sexual violence in New York City. Evaluation and program planning, 66, 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Daruwalla N, & Osrin D (2019). Understanding participation dilemmas in community mobilisation: can collective action theory help? J Epidemiol Community Health, 73(1), 90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Morrison J, Saville N, Yadav SS, Shrestha B, Manandhar D, … Skordis-Worrall J (2018). Do Participatory Learning and Action Women’s Groups Alone or Combined with Cash or Food Transfers Expand Women’s Agency in Rural Nepal? The journal of development studies, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher A, de Wet J, Bonell CP, Strange V, Phetla G, Proynk PM, … Hargreaves JR (2011). Promoting critical consciousness and social mobilization in HIV/AIDS programmes: lessons and curricular tools from a South African intervention. Health Education Research, 26(3), 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Abramsky T, Kone D, Bakayoko-Topolska M, … Watts C (2014). Working with men to prevent intimate partner violence in a conflict-affected setting: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial in rural Cote d’Ivoire. BMC public health, 14, 339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health, 19(1), 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal F, Fletcher A, Shackleton N, Elbourne D, Viner R, & Bonell C (2015). The three stages of building and testing mid-level theories in a realist RCT: a theoretical and methodological case-example. Trials, 16(1), 466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jejeebhoy SJ, & Santhya KG (2018). Preventing violence against women and girls in Bihar: challenges for implementation and evaluation. Reprod Health Matters, 26(52), 1470430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, Jama N, Dunkle K, Puren A, & Duvvury N (2008). Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 337, a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Ju G, Mark GY, Cohen R, Garcia-Santiago O, & Nguyen P (2008). Community mobilization and its application to youth violence prevention. Am J Prev Med, 34(3 Suppl), S5–S12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilford RJ, Oyebode O, Satterthwaite D, Melendez-Torres GJ, Chen YF, Mberu B, … Ezeh A (2017). Improving the health and welfare of people who live in slums. Lancet, 389(10068), 559–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman SA, Leddy AM, Neilands TB, Ahern J, MacPhail C, Wagner RG, … Pettifor A (2018). Village community mobilization is associated with reduced HIV incidence in young South African women participating in the HPTN 068 study cohort. J Int AIDS Soc, 21 Suppl 7, e25182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman SA, Maman S, MacPhail C, Twine R, Peacock D, Kahn K, & Pettifor A (2013). Conceptualizing community mobilization for HIV prevention: implications for HIV prevention programming in the African context. PLoS One, 8(10), e78208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M (2004). Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 31(6), 684–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, … Baird J (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 350, h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushongera D, Zikhali P, & Ngwenya P (2017). A multidimensional poverty index for Gauteng province, South Africa: evidence from Quality of Life Survey data. Social Indicators Research, 130(1), 277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Muzyamba C, Groot W, Tomini SM, & Pavlova M (2017). The role of Community Mobilization in maternal care provision for women in sub-Saharan Africa- A systematic review of studies using an experimental design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 17(1), 274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson R, Tilley N, & Tilley N (1997). Realistic evaluation: sage. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock D, & Barker G (2014). Working with men and boys to prevent gender-based violence: Principles, lessons learned, and ways forward. Men and Masculinities, 17(5), 578–599. [Google Scholar]

- Peberdy S, Harrison P, & Dinath Y (2017). Uneven spaces: core and periphery in the Gauteng City-Region (0639911412). Retrieved from Johannesburg: [Google Scholar]

- Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Gottert A, Suchindran CM, Selin A, Peacock D, … MacPhail C (2018). Community mobilization to modify harmful gender norms and reduce HIV risk: results from a community cluster randomized trial in South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc, 21(7), e25134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prost A, Colbourn T, Seward N, Azad K, Coomarasamy A, Copas A, … Lewycka S (2013). Women’s groups practising participatory learning and action to improve maternal and newborn health in low-resource settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 381(9879), 1736–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ (2006). Collective efficacy theory: Lessons learned and directions for future inquiry. Taking stock: The status of criminological theory, 15, 149–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen G, Emmons K, Hunt MK, & Johnston D (1998). Implications of the results of community intervention trials. Annual review of public health, 19(1), 379–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern E, & Nyiratunga R (2017). A process review of the Indashyikirwa couples curriculum to prevent intimate partner violence and support healthy, equitable relationships in Rwanda. Social sciences, 6(2), 63. [Google Scholar]

- Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra VS, Khandekar S, Singh AK, Das SS, … Barker G (2008). Promoting gender equity as a strategy to reduce HIV risk and gender-based violence among young men in India. [Google Scholar]

- Victora CG, Habicht J-P, & Bryce J (2004). Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized trials. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 400–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser MJ, & Schoeman JB (2004). Implementing a community intervention to reduce young people’s risks for getting HIV: Unraveling the complexities. Journal of Community Psychology, 32(2), 145–165. [Google Scholar]

- Wagman JA, Gray RH, Campbell JC, Thoma M, Ndyanabo A, Ssekasanvu J, … Brahmbhatt H (2015). Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: analysis of an intervention in an existing cluster randomised cohort. Lancet Glob Health, 3(1), e23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterkeyn J, & Cairncross S (2005). Creating demand for sanitation and hygiene through Community Health Clubs: a cost-effective intervention in two districts in Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med, 61(9), 1958–1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]