To the Editor,

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19), caused by a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has spread rapidly around the world. Currently, the identification of this disease is mainly conducted by using nasopharyngeal swabs, 1 but the presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in feces of COVID‐19 patients indicates the possibility of transmission via fecal‐oral route. 2 , 3 , 4

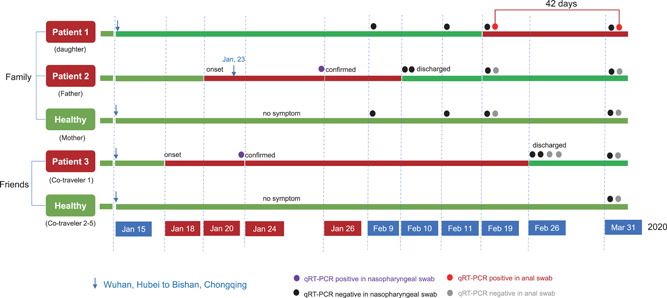

Herein, we report the distinctive clinical characteristics of an asymptomatic case in which SARS‐CoV‐2 viral nucleotide detection was positive in anal swabs but negative in nasopharyngeal swabs for such a long period (42 days). In this case, an 8‐year‐old girl (patient 1) did not show any clinical symptoms, abnormal chest computed tomography (CT) image findings, or a decreased lymphocyte count. Moreover, she was identified as an asymptomatic case on February 19 and until now she did not become a confirmed patient with either respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Patient 1 lived with her family in the Hanjiang District of Wuhan (Hubei, China) for a long time. Because of the coming Spring Festival in China, on 15 January 2020, patient 1 traveled from Wuhan to Bishan District of Chongqing city with her mother and five other persons by high‐speed rail. Excluding patient 1's mother, one of the other five travelers (patient 3, 39‐year‐old female, with apparent clinical manifestations) was a COVID‐19 patient with onset on January 18 and confirmation on January 24. This group of people stayed in the house of patient 3 for a night in the Bishan District. On the morning of the next day, patient 1 was brought back to her home by her mother. On January 23, patient 1's father returned from Wuhan alone by vehicle (patient 2, 31 years old), but he showed clinical symptoms on January 20; symptoms included low‐grade fever, dry cough with occasional white mucus, muscle ache, and loose stools, all of which lasted for 5 days. On January 25, the patient 2 was admitted to the Bishan People's Hospital with a body temperature of 37.5°C, respiratory symptoms, a sharply reduced lymphocyte count, abnormal CT image findings and positive quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) results of nasopharyngeal swabs. The patient 1 and her mother were, therefore, quarantined for medical observation in their own house. Two sets of nasopharyngeal swab samples from the patient 1 and her mother were collected and tested on February 9 and 11. Both qRT‐PCR tests reported negative results for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection, and they had no apparent clinical symptoms during the observation period. On February 10, after patient 2 recovered in the hospital for 16 days, he was allowed to return home for an additional 14 days of quarantine. On February 19, nasopharyngeal and anal swabs samples from all family members were collected by staff of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. In the observed results, the patient 1 was identified as an asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infected case, as the anal swab was positive but the nasopharyngeal swab was negative according to the qRT‐PCR results, and the anal swab of the patient 1 remained unchanged until March 31. In contrast, both her father and mother did not show any clinical signs or positive viral nucleotides in the nasopharyngeal and anal swabs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Chronology of symptom onset and identification of positive SARS‐CoV‐2 findings on quantitative RT‐PCR. SARS‐CoV‐2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

In this family cluster, the patient 1 had contact with a confirmed COVID‐19 patient on January 15 (patient 3) and January 23 to 25 and February 10 to 19 (patient 2). To date, no clinical symptoms have been observed (Figure S1 and Table S1), and no positive results were detected in nasopharyngeal swabs from the patient 1 in nucleic acid tests, but evidence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection was detected in an anal swab on February 19. It is worth alerting the observed positive results in the anal swabs could last up to 42 days but the nasopharyngeal swabs did not show any positive results. The presence of immunoglobulin G antibodies in patient 1's serum only is indicative of past exposure (Table S2). If patient 1 was infected by patient 3 or by her father on January 23 to 25, she was asymptomatic with positive viral nucleotides in anal swabs. However, if patient 1 was infected by her father after leaving the hospital on February 10 to 19, it suggests that a patient with a negative nasopharyngeal swab after several days of illness may still be capable of transmitting the virus to others. The nasopharyngeal and anal swabs of the patient 2 did not show any positive qRT‐PCR results, and whether asymptomatic patient 1 was capable of transmitting the virus to others remains unknown, although her mother never became infected even though she was in contact with confirmed COVID‐19 and asymptomatic patients.

Recent evidence demonstrates that SARS‐CoV‐2 viral RNA is detectable in feces during the recovery period of COVID‐19 pneumonia. 5 , 6 Intriguingly, studies have also illustrated that both adult and children patients of COVID‐19 persistently tested positive on anal swabs even after nasopharyngeal testing was negative. 7 , 8 This case will further provide the new information that, besides confirmed COVID‐19 patients, the asymptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infected case can be persistently tested positive in the stool samples but negative in nasopharyngeal swabs for a long time.

The number of asymptomatic infections is rapidly increasing all around the world. 9 Asymptomatic patients may be unaware of their SARS‐CoV‐2 infection status and, therefore, transmit the virus to others unknowingly if they are not isolated for medical observation. To control the quick and widespread transmission of COVID‐19 as early as possible, family members of confirmed cases should be closely monitored. More importantly, to rule out asymptomatic infection by SARS‐CoV‐2, not only nasopharyngeal swabs but also anal swabs are extremely important for detection.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

CC: writing—original draft, conceptualization. ZZ: writing—original draft, validation. XJ: writing—original draft, formal analysis. JQ: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. XW: investigation, resources. ML: resources, supervision.

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the New Coronavirus Infection Pneumonia Prevention and Control Project of Bishan Science and Technology Bureau (bskj2020008) and Emerging Project for New Coronavirus Infection and Treatment of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (KYYJ202005).

Funding Information New Coronavirus Infection Pneumonia Prevention and Control Project of Bishan Science and Technology Bureau, Grant/Award Number: bskj2020008; Emerging Project for New Coronavirus Infection and Treatment of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission, Grant/Award Number: KYYJ202005

Xuejun Jiang, Mei Luo, and Zhen Zou contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Xu Wang, Email: 875777340@qq.com.

Chengzhi Chen, Email: chengzhichen@cqmu.edu.cn.

Jingfu Qiu, Email: jfqiu@126.com.

REFERENCES

- 1. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumoniain China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727‐733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen Y, Chen L, Deng Q, et al. The presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 RNA in feces of COVID‐19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang J, Wang S, Xue Y. Fecal specimen diagnosis 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020;92:680‐682. 10.1002/jmv.25742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nouri‐Vaskeh M, Alizadeh L. Fecal transmission in COVID‐19: a potential shedding route. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu J, Xiao Y, Shen Y, et al. Detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 by RT‐PCR in anal from patients who have recovered from coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang T, Cui X, Zhao X, et al. Detectable SARS‐CoV‐2 viral RNA in feces of three children during recovery period of COVID‐19 pneumonia. J Med Virol. 2020. 10.1002/jmv.25795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wu Y, Guo C, Tang L, et al. Prolonged presence of SARS‐CoV‐2 viral RNA in faecal samples. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:434‐435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, et al. Characteristics of pediatric SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med. 2020;26:502‐505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li R, Pei S, Chen B, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV2). Science. 2020;368(6490):489‐493. 10.1126/science.abb3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information

Supporting information

Supporting information