Abstract

A 66‐year‐old woman diagnosed clinical manifestation of extensive hard palate hyperpigmentation is presented. Due to historic of rheumatoid arthritis and use of chloroquine phosphate for 3 years, exogenous hyperpigmentation associated with the drug was included among the possible diagnoses. Incisional biopsy was performed and the histopathological exam confirmed exogenous hyperpigmentation compatible with chloroquine use. The patient was referred to the rheumatologist and the ophthalmologist for evaluation of the continuity of the chloroquine use. After one year of follow‐up, no changes were seen in the hyperpigmentation nor other clinical changes. Hyperpigmentation of the hard palate by the use of chloroquine is one of the adverse effects of the chronic use of this drug and does not require specific treatment. The adequate anamnesis and the knowledge about the adverse effects of the drug allowed an adequate therapeutic approach in the case.

1. INTRODUCTION

Pigmentary changes in the oral mucosa may be caused by many medications, including antimalarial drugs (chloroquine phosphate, hydroxychloroquine, quinidine and quinacrine), tranquilizers (chlorpromazine), chemotherapeutic drugs (doxorubicin, busulfan and cyclophosphamide), antiretroviral agents (AZT and ketoconazole), antibiotics (minocycline) and laxatives (phenolphthalein). 1 The pathogenesis underlying drug pigmentation can be categorized as arising from the deposition of metabolites or drugs in the dermis and epidermis, melanin deposition with or without melanocyte augmentation and drug‐induced post‐inflammatory mucosal changes. 2

Chloroquine phosphate, classified as an antimalarial agent due to its immunosuppressive potential and anti‐inflammatory action, is also used for the treatment systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis, in addition to other dermatological conditions. 1 Recent studies have brought attention to its possible benefit also in the treatment of patients infected by the novel emerged Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), 3 , 4 , 5 a pandemic that first broke out in China and spread rapidly worldwide. 4 , 5 , 6 In so doing, the use of chloroquine phosphate is expected to increase considerably, therefore, it is important to recognize its possible side effects.

In this paper, the case of a 66‐year‐old woman diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and using chloroquine phosphate for 3 years, with clinical manifestation of extensive hard palate hyperpigmentation is presented.

2. CASE REPORT

A 66‐year‐old female patient attended the Outpatient Clinic of the Mato Grosso Cancer Hospital presenting as main complaint the presence of extensive palate stain that initially had a light purple hue that evolved to bluish‐black in about one year. The patient reported rheumatoid arthritis, cataract, gastroesophageal reflux, hiatal hernia, thyroidectomy and use of levothyroxine sodium, chondroitin, chloroquine, glucosamine, prednisolone and alendronate.

Clinical examination showed a painless, poorly delimited bluish‐black spot on hard palate with approximately 3 cm in diameter, and teeth with different restorative materials (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Clinical aspect of the color alteration present in the hard palate with a diameter of approximately 3 cm and evolution of 1 year

In view of the clinical characteristics, incisional biopsy was scheduled, with diagnostic hypotheses for tattooing by amalgam, melanoma and melanocytic nevus. The report of rheumatoid arthritis under continuous chloroquine therapy 250 mg (1 tablet, once daily) included exogenous hyperpigmentation associated with the drug among as the main possible diagnoses. The patient was unable to associate the duration of medication use and the appearance of pigmentation.

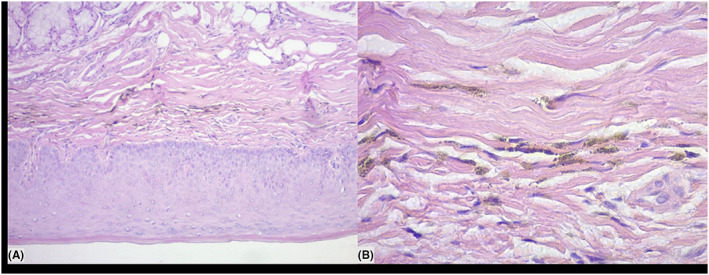

The intervention was uneventful. The collected material was sent for histopathological examination along with the patient's clinical history. The diagnosis was exogenous hyperpigmentation compatible with chloroquine use. The histological sections revealed a fragment of oral mucosa covered by parakeratinized stratified paved epithelium. On the lamina propria, in the subepithelial region and arranged in bands, exogenous black‐colored pigments were noted, which sometimes were phagocytosed by macrophages (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

A, Histological sections showing fragment of oral mucosa coated with parakeratinized stratified paved epithelium. B, Exogenous pigmentation of blackish color arranged in bands

The patient was referred to her rheumatologist, informing about the diagnosis. He maintained the medication. She was also referred to the ophthalmologist for evaluation due to the chloroquine retinotoxicity potential.

The patient has been under follow‐up for one year, with no other clinical changes suggestive of chloroquine adverse effect, and the bluish black palate shows no change in presentation.

3. DISCUSSION

This paper presents the clinical case of a 66‐year‐old female patient with extensive 1‐year hard palate pigmentation and 1‐year follow‐up. Pigmentations of the oral mucosa can be classified as exogenous when they result from traumatic implantation of materials such as silver amalgam and graphite and endogenous as a result of red blood cell destruction or increased melanin production. Oral pigment changes of endogenous origin are mainly related to the use of tetracycline, minocycline, antimalarial agents, oral contraceptives, chemotherapeutic agents and some drugs used in AIDS therapy. 7

Chloroquine and other quinine derivatives are drugs used to treat malaria, cardiac arrhythmia, lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis 7 , 8 and possibly in the treatment of patients infected by the novel emerged coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2). 3 , 4 , 9 Oral pigmentations associated with chronic use of chloroquine are characteristically bluish in color. Most of the time, only the hard palate is involved, with a remarkable demarcation between it and the soft palate. 7 , 8 Chronic use of such medication may also develop pathological pigmentation of the face, upper and lower limbs, as well as irreversible retinal damage. 10 Adverse effects of chronic chloroquine use include xerostomia, skin hyperpigmentation and pruritus. Less commonly, there is mucosal hyperpigmentation, nail dystrophy, and hair hypopigmentation. At the stomatological level, areas of bluish‐black‐blue pigmentation of varying size and well‐circumscribed may appear, usually in the oral mucosa and hard palate, not affecting the soft palate. 11 In the present case, the patient was on therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, using chloroquine for 3 years and presented the oral manifestation an extensive bluish‐black hyperpigmentation limited to the hard palate as the only adverse effect of the chronic use of the medication.

The diagnosis of chloroquine pigmentation is basically guided by the history of drug use and the clinical manifestations of the patient. In typical cases or with incomplete history, a biopsy is performed to aid the diagnosis. In atypical cases, biopsy is crucial to rule out melanoma. 12 Given the long‐term history of chloroquine, the main diagnostic hypothesis was drug‐induced endogenous oral hyperpigmentation. Differential diagnoses are cited as melanocytic nevus, amalgam tattooing, Addison's disease, vitamin B12 deficiency and melanoma. 8

Microscopically, hyperpigmentation of the oral mucosa of medicinal origin is characterized by an abnormal number of melanocytes in the epithelium and the presence of pigment granules within the lamina propria, between collagen fibers and within macrophages. When there are granules in the reticular lamina propria and lack of melanin deposition in the basal cell layer, it is pointed to the hyperpigmentation due to the use of hydroxychloroquine. 13

An incisional biopsy was performed and submitted to histopathological examination, whose report described the presence of blackened exogenous pigments in the lamina propria and subepithelial region, sometimes phagocytized by macrophages, as well as overlying epithelium with normal appearance. These characteristics are found in other cases described previously, confirm the diagnosis of drug‐induced oral pigmentation and rule out the hypothesis of neoplastic development. 1 , 14

There is no need for treatment in these cases, and the possibility of reducing or stopping medication can be evaluated by the rheumatologist. It is also important to refer the patient for ophthalmologist evaluation due to the potential for chloroquine retinotoxicity. 15 The therapeutic approach adopted in this case report was to refer the patient to the ophthalmologist, as well as to keep her in periodic dental and rheumatological clinical follow‐up.

Professionals shall jointly assess the risks and benefits of maintaining or stopping medication. As the use of chloroquine phosphate is probable to increase, it is important that clinicians know this uncommon side effect.

4. CONCLUSION

Hyperpigmentation of the hard palate by the use of chloroquine is one of the adverse effects of the chronic use of this drug and does not require specific treatment. The adequate anamnesis, the dentist's knowledge about the adverse effects of the drug and the establishment of differential diagnoses allowed an adequate therapeutic approach in the case presented and the referral to other medical areas for multidisciplinary approach.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

Géssica Vasconcelos Godinho and Ana Luiza Lima Medeiros Paz have made substantial contributions to the conduction of the clinical case, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data;

Elâine Patrícia Alves de Araújo Gomes and Cristiane Loreda Garcia were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content;

Luiz Evaristo Ricci Volpato have made substantial contributions to conception and design of the manuscript; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. Each author participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

REFERENCES

- 1. Melo‐Filho MR, Silva CA, Dourado MR, Pires MB, Pêgo SP, Freitas EM. Palate hyperpigmentation caused by prolonged use of the anti‐malarial chloroquine. Head Neck Pathol. 2012;6:48‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sreeja C, Ramakrishnan K, Vijayalakshmi D, Devi M, Aesha I, Vijayabanu B. Oral pigmentation: a review. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2015;7(Suppl 2):S403‐S408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Touret F, de Lamballerie X. Of chloroquine and COVID‐19. Antiviral Res. 2020;177:104762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dong L, Hu S, Gao J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14(1):58‐60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gao J, Tian Z, Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID‐19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci Trends. 2020;14(1):72‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yao X, Ye F, Zhang M, et al. In vitro antiviral activity and projection of optimized dosing Design of Hydroxychloroquine for the treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). Clin Infect Dis. 2020. pii: ciaa237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kauzman A, Pavone M, Blanas N, Bradley G. Pigmented lesions of the oral cavity: review, differential diagnosis, and case presentations. J Can Dent Assoc. 2004;70(10):682‐683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andrade BA, Padron‐Alvarado NA, Muñoz‐Campos EM, Morais TL, Martinez‐Pedraza R. Hyperpigmentation of hard palate induced by chloroquine therapy. J Clin Exp Dent. 2017;9(12):e1487‐e1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colson P, Rolain JM, Raoult D. Chloroquine for the 2019 novel coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;55(3):105923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ferrazzo KL, Payeras MR, Surkamp P, Danesi CC. Pathological pigmentation of the skin and palate caused by continuous use of chloroquine: case report. J Oral Diag. 2017;2(1):1‐5. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Horta‐Bass G. Hiperpigmentación de la mucosa oral y discromia ungueal inducida por cloroquina. Reumatol Clin. 2017;14(3):177‐178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klenegger CL, Hammond HL, Finkelstein MW. Oral mucosal hyperpigmentation secondary to antimalarial drug therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;90(2):189‐194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tosios KI, Kalogirou EM, Sklavounou A. Drug‐associated hyperpigmentation of the oral mucosa: report of four cases. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 2018;125(3):e54‐e66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andrade BA, Fonseca FP, Pires FR, et al. Hard palate hyperpigmentation secondary to chronic chloroquine therapy: report of five cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40(9):833‐838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lerman MA, Nadeem K, Guze KA, Woo SB. Pigmentation of the hard palate. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;107:8‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]