Abstract

Objective

Patients with rheumatic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and lupus have increased risk of infection and are treated with medications that may increase this risk yet are also hypothesized to help treat COVID‐19. We set out to understand how the COVID‐19 pandemic has impacted the lives of these patients in the United States.

Methods

Participants in a US‐wide longitudinal observational registry responded to a supplemental COVID‐19 questionnaire by e‐mail on March 25, 2020, about their symptoms, COVID‐19 testing, health care changes, and related experiences during the prior 2 weeks. Analysis compared responses by diagnosis, disease activity, and new onset of symptoms. Qualitative analysis was conducted on optional free‐text comment fields.

Results

Of the 7061 participants invited to participate, 530 responded, with RA as the most frequent diagnosis (61%). Eleven participants met COVID‐19 screening criteria, of whom two sought testing unsuccessfully. Six others sought testing, three of whom were successful, and all test results were negative. Not quite half of participants (42%) reported a change to their care in the prior 2 weeks. Qualitative analysis revealed four key themes: emotions in response to the pandemic, perceptions of risks from immunosuppressive medications, protective measures to reduce risk of COVID‐19 infection, and disruptions in accessing rheumatic disease medications, including hydroxychloroquine.

Conclusion

After 2 weeks, many participants with rheumatic diseases already had important changes to their health care, with many altering medications without professional consultation or because of hydroxychloroquine shortage. As evidence accumulates on the effectiveness of potential COVID‐19 treatments, effort is needed to safeguard access to established treatments for rheumatic diseases.

Introduction

As the novel COVID‐19 became a pandemic, there were early signs that people who were older, had a greater number of health conditions, or had immunodeficiencies would be at greater risk of contracting it and/or having more severe disease 1, 2. Patients with rheumatic diseases are known to be at higher risk of infection because of immune dysregulation, comorbidities, and immune‐modulating treatments 3, 4, 5. Many of these diseases (eg, rheumatoid arthritis [RA]) affect patients of an older age on average 6. Beyond the typical challenges of self‐managing a chronic disease, disease management has become significantly more complex with the implementation of social distancing, including limiting nonessential health care visits. This has led to confusion about how patients with rheumatic diseases should balance managing their disease and reducing their risk of infection 7, 8.

In addition, there were early reports that treatments typically used for rheumatic diseases might be effective against COVID‐19 9. Most notably, in vitro studies and a small cohort study reported that hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) showed some benefits in treating COVID‐19 10, 11, 12. HCQ is a commonly used conventional disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) that reduces flares and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus and is a common treatment for RA and other rheumatic diseases, In a small case‐series, the interleukin‐6 (IL‐6) inhibitor tocilizumab, a biologic DMARD, also showed promise for treating respiratory manifestations related to COVID‐19 13. There are several ongoing clinical trials examining the use of tocilizumab or sarilumab as treatment for COVID‐19 14. These early reports and the emergency authorization by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of HCQ as a treatment for COVID‐19 have led to critical shortages in medication availability during a time when regular access to medication is inherently more difficult 15.

The objective of this study was to understand how patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in the United States have been impacted by the COVID‐19 pandemic through a one‐time COVID‐19 questionnaire querying their experiences during the last 2 weeks of March 2020.

Patients and Methods

The study population consisted of participants in FORWARD, The National Databank for Rheumatic Diseases, a longitudinal open‐enrollment observational patient registry 16. Participants are volunteers recruited primarily by US rheumatologists to complete comprehensive, semiannual questionnaires online, by mail, or by telephone interview. Participants included in this analysis responded to an online supplemental COVID‐19 questionnaire focused on their experiences around COVID‐19 symptoms, testing, and medication access in the 2 weeks prior to questionnaire completion. The supplemental COVID‐19 questionnaire was sent via an e‐mail link on March 25, 2020, to all FORWARD participants who had been invited to complete the current semiannual questionnaire. Responses to the supplemental questionnaire were collected between March 25 and April 1, 2020. In order to be included in this study, participants must have previously completed a semiannual questionnaire within the last 2 years. This study was approved by the Via Christi Hospitals Wichita, Inc., Institutional Review Board (IRB00001674), and all participants consented to participate.

Study variables

COVID‐19 questionnaire

Participants were asked about their rheumatic disease activity, development of any new symptoms (fever, cough, sore throat, shortness of breath, fatigue, muscle pain, headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, chest pain, abdominal pain, loss/change in taste or smell, and anxiety), testing for COVID‐19, and any changes in their rheumatology treatment plan in the previous 2 weeks (See Appendix for full list of items). Participants were given the opportunity to share free‐response comments about their experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic.

Semiannual questionnaire

The most recently completed semiannual questionnaire was linked to each participant's COVID‐19 questionnaire. The following were assessed: demographics, including age, sex, race, education level, marital status, urban/rural area, history of smoking, body mass index, and health insurance status; primary rheumatic disease diagnosis; patient‐reported outcome measures, including pain, global severity, fatigue, Health Assessment Questionnaire II (HAQ‐II) score (a validated measure of physical function) 17, and Patient Activity Scale II [PAS‐II] score (a validated measure of disease activity) 18, 19; comorbid conditions, including heart disease, pulmonary disease, diabetes, renal disease, and liver disease; and medication use, including DMARDs, corticosteroids, and nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs.

Screening criteria

Screening criteria were applied to supplemental COVID‐19 questionnaire respondents based on March 20, 2020, CDC recommendations for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing priority 20 and included 1) fever, 2) at least one symptom of acute respiratory illness (new cough, dyspnea, sore throat, chest pain, or loss of taste/smell within the prior 2 weeks), and 3) at least one of the following: is 65 or more years old, is in a long‐term care facility, has an autoimmune diagnosis, has a Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index (RDCI) 21 of at least 2, or is a health care worker/first responder.

Quantitative analysis

Differences between COVID‐19 questionnaire respondents and nonrespondents were assessed with Student's t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Responses to all COVID‐19 items were tabulated, and significance was assessed with χ2 tests. All tests were two‐tailed, and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Logistic regression modeled the association between disease activity and reported cancelation or postponement of appointments, with all sociodemographic information, RDCI, diagnosis, and number of rheumatology and general practitioner visits as covariables. Data were analyzed using Stata version 14.2 22.

Qualitative analysis

Two of the authors (YS and TAS) independently read and open coded the free‐text comments using a grounded theory approach 23, 24, 25. They met to discuss their coding and notes and organized them into themes.

Figure creation

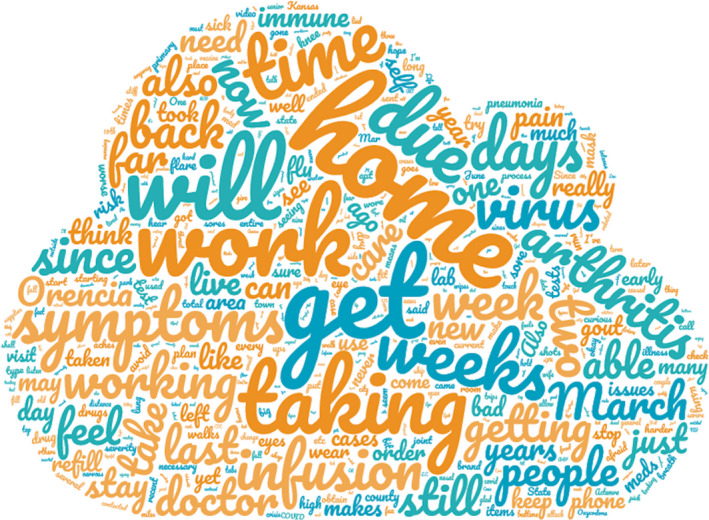

UpSetR version 1.4 was used to generate the UpSet plot 26. Wordclouds.com was used to generate the word cloud, using the cloud graphic from Font Awesome version 5.13 as a template. The relative size of each word represents the frequency with which it appeared in the free‐response comments.

Results

A total of 7061 active FORWARD participants were sent the supplemental COVID‐19 questionnaire. Of those, 530 participants responded during the first 7 days used for this report. RA was the most frequent diagnosis (61%). Geographic distribution was diverse, with respondents representing 49 of 50 states (15% of respondents were from the Northeast, 31% were from the Midwest, 27% were from the South, and 25% were from the West). Compared with nonrespondents, respondents were more likely to be white, to have more education, to have completed their semiannual questionnaire online rather than on paper or by interview, and to have lower disease activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants with rheumatic diseases who were sent the COVID‐19 supplemental questionnaire by response status

| Characteristics | Respondents (n = 530) | Nonrespondents (n = 6531) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 65.0 (10.9) | 64.2 (12.5) | 0.14 |

| Female, % | 84.4 | 84.2 | 0.92 |

| White, % | 93.5 | 90.2 | 0.02 |

| Education, mean (SD), y | 15.3 (1.9) | 14.9 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Married, % | 71.1 | 67.1 | 0.06 |

| Rural, % | 19.8 | 22.5 | 0.15 |

| History of smoking, % | 36.8 | 41.0 | 0.06 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 28.1 (7.5) | 29.0 (7.9) | 0.01 |

| Health insurance, % | 98.9 | 99.0 | 0.79 |

| US geographic distribution, % | |||

| Northeast | 14.9 | 18.2 | <0.01 |

| Midwest | 30.8 | 32.3 | <0.01 |

| South | 27.0 | 27.3 | <0.01 |

| West | 24.7 | 17.8 | <0.01 |

| Semiannual questionnaire | |||

| Online, % | 85.8 | 55.5 | <0.001 |

| Paper, % | 14.2 | 39.6 | <0.001 |

| Interview, % | 0 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Time since completion, d | 211 (92) | 312 (195) | <0.001 |

| Patient‐Reported Outcome Measures | |||

| Pain (0‐10), mean (SD) | 3.1 (2.6) | 3.9 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Global severity (0‐10), mean (SD) | 3.0 (2.3) | 3.7 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Fatigue (0‐10), mean (SD) | 3.5 (2.9) | 4.3 (3.0) | <0.001 |

| HAQ‐II (0‐3), mean (SD) | 0.75 (0.61) | 0.91 (0.67) | <0.001 |

| PAS‐II (0‐3), mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.1) | 3.5 (2.2) | <0.001 |

| Primary diagnosis, % | |||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 60.6 | 62.1 | 0.34 |

| Osteoarthritis | 11.1 | 12.8 | 0.34 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 5.7 | 5.1 | … |

| Other | 22.6 | 20.0 | 0.34 |

| Comorbid conditions, % | 0.34 | ||

| Heart disease | 22.1 | 22.9 | 0.65 |

| Pulmonary disease | 32.3 | 31.3 | 0.63 |

| Diabetes | 11.7 | 14.4 | 0.09 |

| Renal disease | 14.3 | 14.3 | 0.96 |

| Liver disease | 9.4 | 8.1 | 0.28 |

| Medications, % | |||

| Conventional DMARD | 52.6 | 46.9 | 0.01 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 17.7 | 19.5 | 0.31 |

| Biologic DMARD | 39.0 | 37.1 | 0.37 |

| IL‐6 inhibitor | 3.2 | 3.8 | 0.49 |

| JAK inhibitor | 7.0 | 5.1 | 0.07 |

| Corticosteroid | 18.1 | 18.6 | 0.79 |

| NSAID | 38.8 | 35.3 | 0.10 |

Bold value indicates P < 0.05.

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; DMARD, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug; HAQ‐II, Health Assessment Questionnaire II; IL‐6, interleukin 6; JAK, Janus kinase; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug; PAS‐II, Patient Activity Scale II.

Symptoms, screening criteria, and SARS‐CoV‐2 testing

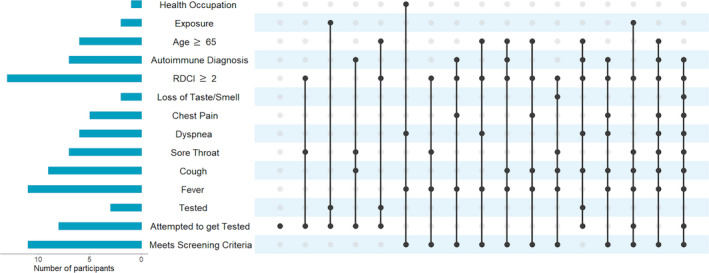

Approximately half of respondents reported experiencing new symptoms potentially associated with COVID‐19 in the 2 weeks prior to questionnaire completion. The most frequently reported new symptoms were fatigue (18%), anxiety (16%), headache (13%), muscle pain (12%), and cough (10%) (Table 2). Of the 530 respondents, 11 (2%) met COVID‐19 screening criteria. Of those 11, two respondents had sought testing and, despite one of them reporting exposure to a confirmed case, neither received it. In addition, six others who did not meet the screening criteria reported an attempt to get tested for COVID‐19, and three received testing. None tested positive for SARS‐CoV‐2 (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Frequency of new symptoms a

| Symptom | Participants Reporting, % |

|---|---|

| Fever | 2.8 |

| Cough | 9.9 |

| Sore throat | 8.5 |

| Shortness of breath | 4.1 |

| Tiredness (fatigue) | 17.9 |

| Muscle pain | 11.6 |

| Headache | 13.0 |

| Diarrhea, vomiting, or nausea | 5.7 |

| Chest pain | 2.4 |

| Pain or discomfort in upper abdomen | 2.6 |

| Pain or discomfort in lower abdomen | 3.7 |

| Loss/change in taste or smell | 1.6 |

| Nervousness (anxiety) | 16.2 |

| None of these | 58.4 |

Participants were asked if they had experienced any new symptoms in the 2 weeks prior to questionnaire completion; they selected from a provided list of symptoms related to COVID‐19.

Figure 1.

UpSet plot summarizing risk factors, symptoms, and testing experiences for each participant who met screening criteria and/or attempted to get tested for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Each vertical line represents an individual participant, and each solid circle indicates that the participant reported that new symptom or testing experience or has the specified risk factor. All participants who received a test tested negative. No respondents were in a long‐term care facility. Exposure indicates that the participant reported known exposure to a COVID‐19–positive patient. Nonautoimmune diagnoses in this cohort are osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia. RDCI, Rheumatic Disease Comorbidity Index.

Changes in rheumatology care

Of the 530 COVID‐19 questionnaire respondents, 471 answered questions about changes in their rheumatology care. Of these, 197 respondents (42%) reported some change to their care in the previous 2 weeks. Of the 197, 48% reported canceled or postponed appointments, 24% switched to teleconference appointments, 14% reported self‐imposed changes to their medication list or dose, 11% reported physician‐directed changes to their medication list or dose, 10% were unable to obtain their medication, and 4% were unable to reach their rheumatology office. Respondents with higher disease activity were more likely to report canceled or postponed appointments, even after controlling for demographics, comorbidities, and frequency of rheumatology/general practitioner appointments in the past (odds ratio 2.4 [95% confidence interval 1.3‐4.6]; P < 0.01). Respondents who reported experiencing new symptoms associated with COVID‐19 in the last 2 weeks were more likely to have had medications added or removed by their physician (Table 3).

Table 3.

Reported changes in rheumatology care caused by COVID‐19 in the previous 2 weeks by prior disease activity and new symptoms a

| Change in Care | All (N = 471), % | Disease Activity b | New Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 290), % | High (n = 128), % | No (n = 257), % | Yes (n = 214), % | ||

| Canceled or postponed appointments | 20.8 | 16.6 | 31.3 | 18.3 | 23.8 |

| Switched to teleconference appointments | 10.6 | 7.9 | 14.8 | 10.9 | 10.3 |

| Could not reach the rheumatology office | 1.5 | 0.3 | 2.3 | 0 | 3.3 |

| Could not obtain my medications | 4.2 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

| Physician changed the dose of patient's medication(s) | 2.5 | 2.1 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 3.7 |

| Physician added or removed medication(s) | 2.5 | 1.4 | 4.7 | 0.4 | 5.1 |

| Patient changed the dose of my medication(s) | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| Patient added or removed medication(s) | 4.7 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 3.9 | 5.6 |

| Other | 7.4 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 6.6 | 8.4 |

| No change | 58.2 | 62.8 | 50.2 | 63.0 | 52.3 |

Statistically significant differences are shown in bold.

Disease activity was defined by Patient Activity Scale II (PAS‐II), with a PAS‐II score of 3.7 or less as low disease activity and a PAS‐II score of more than 3.7 as high disease activity 27.

Patient experiences

The qualitative analysis identified the following four major themes from 211 respondents’ free‐response comments: emotions in response to COVID‐19‐related experiences, perceptions of risk, protective measures to reduce risk of COVID‐19 infection, and impacts on rheumatic disease treatment and access to care, including medications and rheumatology consultations (Table 4 and Figure 2).

Table 4.

Illustrative quotes for each major theme identified in respondents’ free‐response comments

| Theme | Example Quote |

|---|---|

| Emotions in response to COVID‐19–related experiences | |

| Anxiety/nervousness/worry/fear | “I am not normally a nervous person but thinking of contracting this virus really scares me. I lived, barely, through a H1N1 virus attack of my system 5 years ago but this is a brand new virus and it really makes me nervous.” |

| Desire to reduce risk of COVID‐19 | “I am taking the threat of the virus seriously. I am self isolating and having my groceries and medications delivered.” |

| Not worried about COVID‐19 | “I am not worried about COVID19 and think the entire thing is overblown.” |

| Uncertainty | “I started with dry cough, nasal drip with no congestion at all. Then shortness of breath two days later, low grade fever. Headache, severe fatigue, muscle aches in arms and legs, sore throat that comes and goes. Developed pneumonia around 10 days in. While I tested negative for COVID‐19 this is suspect because I never get sick and I haven't had pneumonia since childhood (once). I work from home and have no reason to have acquired pneumonia.” |

| Frustration | “Unable to get name brand plaquenil due to covid 19 virus usage. They don't seem to care about people that need the drug for immune diseases.” |

| Sadness | “I miss my grandbabies. I watched one 3 days a week. I cried myself to sleep missing them except for the last 3 days finally. My daughter sends pics. Working on video chat situations.” |

| Gratefulness | “I am so grateful that my family understands my health issues and is staying away.” |

| Hope | “I am hopeful we will escape this pestilence! and I hope you will, too.” |

| Wanting to help | “I flew back home from [State A] via [City 1] to [City 2], [State B] on March 19th. I was exhausted for two days after traveling during which time I had a lowgrade fever and a headache. On the third day, I developed a bad cough with a tightness in my chest that last for about a week. About the sixth day, I called my primary doctor who recommended the hot tea and normal things of comfort. I had started to feel a bit better by then. I really didn't want to use testing supplies when I was keeping myself in quarantine since I arrived home from [State A] anyway.” |

| Managing negative emotions/stress | “The stress of the pandemic has affected my immune system. It's like a domino effect. I started with sores in my mouth, then in my ear, which triggered the polychondritis, which causes pain and pressure on the left side of my head, which makes me fatigued more than usual, which frustrates me and makes me depressed and triggers the fibromyalgia and colitis. During isolation I must focus harder to find those things I can do, instead of focusing on those I can't. There is still joy to be found.” |

| Perceptions of risk | |

| Increased risk due to age, chronic conditions, or potential exposure to infected people | “I have put my [biologic] on hold, with the concurrence of my rheumatologist. This is because my husband is a clinician who has likely exposure at his hospital; we live in [city], where COVID‐19 is present.” |

| Increased risk due to taking immunosuppressive medications | “I think my RA is more active over past 3‐4 months since I decreased dose of Methotrexate from 7 to 6 tabs 2.5mg/week in Dec2019. I am afraid to increase it due to Covid 19.” |

| Personal limit for acceptable/unacceptable risk | “I work in healthcare and I plan to go off my immuno‐suppressants if I am exposed. I plan to stay home if we get a case of COVID‐19 where I work. I go to work; I come home. Don't go to the stores. We have 21 cases in my county.” |

| Protective measures to reduce COVID‐19 infection | |

| Self‐isolation/social distancing | “Because [State] has not placed a quarantine or shelter‐in‐place directive asking only for social distancing, I am still taking my walks and trying to avoid all the people who never came and now use the area for a touch of nature. Some of the trails are narrow and it's difficult to get the entire 6’ off to the side. However in general, people are respecting the 6’ whenever possible. I continue to grocery shop taking advantage of senior hours whenever possible, wearing gloves, making my own alcohol wipes when picking up items and cleaning the gloves before removing them etc.” |

| Canceling medical appointments that can be postponed | “I cancelled my cardiologist appointment because of covid‐19 fears. I'm debating on whether to keep my doctors appoints I have for next month.” |

| Working from home | “I had to strongly advocate for myself at work to protect myself. I have completely switched all work activities to telemedicine and am working 100% from home with the support of my division.” |

| Canceling travel plans | “I had plans to return to my home in [State] within the next two weeks. I am not sure if I will as [State] has the highest incidences of Covid‐19. I live Upstate but there have been many cases present there and testing is restricted.” |

| Wearing masks or gloves when in close contact with others | “Shopping in the grocery store is very dangerous right now. I wear a mask but people do not social distance. There are no available wipes for carriages, very unhealthy using payment devices when hand sanitizer is not available after touching buttons for pin #…” |

| Impacts on treatment and access to care | |

| Stopping DMARDs to lessen risk of COVID‐19 | “Stopped taking Leflunomide ‐ concerned about immunosuppressive effect” |

| Medical appointments canceled or switched to telephone or video consultations | “I do have an appointment with my primary care doctor for a regular checkup next Monday and that has been switched from an in‐person visit to a telephone appointment at their request. An online video appointment was also available but we decided a phone call would be best.” |

| Unavailability of medications (especially hydroxychloroquine) | “I tried to get one extra refill on my hydroxychloroquine, after Trump lied about it being useful for cv‐19, because I could see that would cause a run on the drug. I was denied the refill by my pharmacy provider, [pharmacy name], because it was not yet due for refill. After reading that the AHIP was urging companies to allow an extra refill for necessary maintenance medications, I wrote an enote to [pharmacy name] asking them to reconsider their denial and send me the medication now so that I have it to assure continuity of my treatment plan in the future. I have yet to hear back from them.” |

| Loss of health care coverage | “I may lose health care coverage within the next 30 days due to economic changes during this crisis. This may severely affect my rheumatology care.” |

Abbreviation: DMARD, disease‐modifying antirheumatic drug.

Figure 2.

Word cloud demonstrating the top themes and most frequently seen words in respondents’ free‐response comments.

Emotions in response to COVID‐19‐related experiences

The most commonly reported emotions were anxiety, nervousness, worry, and fear. Respondents worried about being infected and developing COVID‐19, whether they would survive an infection, how their medications would affect their risk, and the impact of the pandemic on access to medications and health care. Some noted that the anxiety/stress seemed to worsen their arthritis symptoms. In response to the threat of COVID‐19, most respondents reported a desire to reduce their risk and take actions to protect themselves. Only a small minority of participants expressed a lack of worry toward COVID‐19.

Respondents also reported feeling uncertain about whether to stop taking their medications as well as whether their symptoms were due to COVID‐19 or another condition, such as allergies. They felt frustrated when confronted with difficulties in accessing medication or obtaining permission to work from home. Practicing social distancing caused feelings of sadness and loneliness in respondents who could no longer see family and friends in person.

A few commenters expressed positive emotions such as feeling grateful (eg, for the support of family or colleagues), hopeful, or wanting to help. One person did not want to get tested for COVID‐19 despite having symptoms consistent with COVID‐19 because they had quarantined at home since getting sick and did not want to waste scarce testing supplies. Some acknowledged the need to manage negative emotions and stress.

Perceptions of risk

Many participants expressed beliefs about their increased risk of infection/severe outcomes due to COVID‐19 related to older age, chronic conditions, or exposure through the workplace or contact with family members. Many thought that use of immunosuppressive medications increased their risk/potential severity of COVID‐19 and that stopping such medications could reduce their risk. This belief seemed to stem from previous experiences of being instructed to stop immunosuppressive medications during infections or before surgeries. A minority thought that taking HCQ might lower their risk of developing COVID‐19. Some commenters described setting personal limits for acceptable/unacceptable risk, such as planning to stop going to work once COVID‐19 cases emerged at their workplace.

Protective measures to reduce risk

The majority of respondents described adoption of self‐isolation and social distancing measures, often in response to state shelter‐in‐place orders. They reported actions such as stopping in‐person contact with family and friends, staying at home except to buy groceries and go to medical appointments, having groceries and meals delivered, canceling all but the most critical medical appointments, and canceling travel plans. Some participants were able to arrange working from home, but others (mostly health care workers) could not. Several also discussed wearing masks or using gloves when they needed to go to a grocery store or pharmacy, but that other shoppers did not always respect the recommended distance of 6 feet. Adapting physical activity routines to adhere to social distancing could be challenging because some participants were accustomed to exercising in an indoor public space or with friends. Walking or running outside, sometimes with a pet, was reported as a common alternative activity.

Impacts on treatment and access to care

As discussed above, some participants reported stopping their DMARD use to lessen their risk of infection, sometimes with the approval of their rheumatologist. Others continued to take their medications as usual. Many reported having medical appointments canceled or switched to telephone or video consultations. Infusions were still received as scheduled by most respondents. Availability of medications, particularly HCQ, was a frequent concern, and some people reported being unable to obtain refills from their pharmacy. Some attributed the shortage of HCQ to widespread misinformation that this medication was proven to be an effective treatment for COVID‐19. One person reported concern over losing health care coverage (and as a result, access to rheumatology care) because of the economic impact of COVID‐19.

Discussion

In this study, we report how patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases throughout the United States were impacted by the COVID‐19 pandemic during the latter half of March 2020, the relatively early days of government‐imposed isolation decrees. Although none of the respondents tested positive for COVID‐19, many were already affected by it. One‐fifth of respondents reported postponed or canceled medical appointments, and half reported new symptoms associated with COVID‐19. Our qualitative analysis of participant comments found four themes that highlighted the impact of COVID‐19 on mental health, perceptions that immunosuppressive medications increase the risk of COVID‐19 infection, uncertainty about whether arthritis medications should be continued during the COVID‐19 outbreak, and challenges in accessing HCQ, which has drawn attention as a potential treatment for COVID‐19.

Many respondents were not sure if they should stop their medications—additional evidence‐based guidance is needed in this area for patients and rheumatologists. Recent editorials are recommending not modifying treatment unless symptoms of COVID‐19 manifest 7, 28. It is important for clinicians to be aware that some patients have stopped taking their medications without a recommendation from a health professional.

Respondents with higher disease activity were more likely to have canceled/postponed appointments even after adjustment for several important confounders such as comorbidities and frequency of clinical appointments; it is unclear if this decision was made by the participant or physician because less controlled disease often comes with greater infection risk. Further study is needed to understand how lack of appointments for those likely more in need of health care follow‐up may impact patients’ health. Similarly, patients reporting new symptoms were less likely to have been able to reach their rheumatology clinic and were more likely to have had their physician change their medications; new symptoms likely led patients to contact their physicians, leading to these findings.

Initial reports suggesting HCQ as an effective COVID‐19 treatment 11, 29 have come under increased scrutiny because of questionable methodologies and conclusions 30, 31. The unconfirmed reports of HCQ as a viable treatment option for COVID‐19, along with FDA emergency authorization for use in cases of hospitalization and the resulting shortage/refusal by pharmacies to refill prescriptions, is a major issue for patients and the rheumatology community 32, 33. Although additional studies launch to examine this in greater detail, there is a need to raise awareness that HCQ is not yet a proven treatment or prophylactic for COVID‐19 and is a critical medication for many patients with rheumatic diseases and reduces mortality and flares in patients with lupus 34. As one participant wrote, “I have taken Plaquenil for over 20 years and cannot get any now as it's being used as a possible treatment for Covid19. […] I feel close to hopeless.”

Our study has some important limitations. With a single e‐mail as the basis of our initial questionnaire, there was possible bias toward participants with greater socioeconomic status, fewer symptoms, and lower disease activity. We accounted for this difference by comparing respondents with nonrespondents who had completed their semiannual questionnaire. Future work should also examine the impact on more vulnerable populations, ie, those with lower socioeconomic status or lower education and/or those from racial/ethnic minorities. It is also likely that study participants who were diagnosed with COVID‐19 or hospitalized were not able to respond during this short time period. It is important to note that because this cohort is composed entirely of patients with rheumatic diseases, our ability to differentiate between results that are specific to the rheumatology community and those that are likely to be the case throughout the population is limited. Lastly, comments were not required of participants, and our qualitative analysis was inherently biased toward those who found the need to add additional detail on their experiences beyond our questionnaire.

In summary, we found that after 2 weeks, many participants in the United States with rheumatic diseases already had important changes to their health care, including canceling appointments, which was independently linked to increased disease activity, and altering medications without professional consultation or because of hydroxychloroquine shortage. There were important impacts on mental health and continued uncertainty on how best to treat these diseases and stay protected from COVID‐19. Participants who met priority screening criteria for SARS‐CoV‐2 testing were not tested, those who were tested did not meet screening criteria, and none tested positive. We have planned follow‐up questionnaires with similar questions and the ability to modify them as guidelines change and as participants report testing positive for COVID‐19. As evidence accumulates on the effectiveness of potential COVID‐19 treatments, many of which are used in treating rheumatic diseases, effort is needed to ensure continued access to treatments that have already been proven effective for rheumatic diseases.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be published. Dr. Michaud had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design

Michaud, Wipfler, Shaw, Cornish, Ogdie, Katz.

Acquisition of data

Michaud, Wipfler, Shaw, Simon, Cornish.

Analysis and interpretation of data

Michaud, Wipfler, Shaw, Simon, Cornish, England, Ogdie, Katz.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the additional contributions by Rebecca Schumacher and Dr. Jacob Clarke in the creation and implementation of the supplemental survey. None of this work could be done without the contributions of our participants. In addition, we thank several of our partners who took extra time with home childcare so that we could finish this study in a timely manner.

Dr. Michaud's work is supported by a research grant from the Rheumatology Research Foundation. Dr. England's work is supported by research grants from the Rheumatology Research Foundation and National Institute of General Medical Sciences–supported Great Plains Institutional Development Award for Clinical and Translational Research. Dr. Ogdie has received grants to the University of Pennsylvania from Pfizer and Novartis and to FORWARD Databank from Amgen. FORWARD receives research funding from Novartis, which is one of the manufacturers of hydroxychloroquine.

Drs. Michaud and Wipfler contributed equally to this work.

Ms. Simon has been a consultant and a prior employee for Bristol Meyers Squibb. Dr. Ogdie has served as a consultant for Abbvie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Corrona, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, and Pfizer, and her husband has received royalties from Novartis. No other disclosures relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N England J Med 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China. JAMA 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Atzeni F, Masala IF, di Franco M, Sarzi‐Puttini P. Infections in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017;29:323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hsu CY, Ko CH, Wang JL, Hsu TC, Lin CY. Comparing the burdens of opportunistic infections among patients with systemic rheumatic diseases: a nationally representative cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2019;21:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta B, Pedro S, Ozen G, Kalil A, Wolfe F, Mikuls T, et al. Serious infection risk in rheumatoid arthritis compared with non‐inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: a US national cohort study. RMD Open 2019;5:e000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yazdany J, Bansback N, Clowse M, Collier D, Law K, Liao KP, et al. The Rheumatology Informatics System for Effectiveness (RISE): a national informatics‐enabled registry for quality improvement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1866–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ferro F, Elefante E, Baldini C, Bartoloni E, Puxeddu I, Talarico R, et al. COVID‐19: the new challenge for rheumatologists. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38:175–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pires da Rosa G, Ferreira E. Therapies used in rheumatology with relevance to coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38:370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sarzi‐Puttini P, Giorgi V, Sirotti S, Marotto D, Ardizzone S, Rizzardini G, et al. COVID‐19, cytokines and immunosuppression: what can we learn from severe acute respiratory syndrome? [XXX]. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2020;38:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu J, Cao R, Xu M, Wang X, Zhang H, Hu H, et al. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov 2020;6:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, Hoang VT, Meddeb L, Mailhe M, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12. Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res 2020;30:269–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu X, Han M, Li T, Sun W, Wang D, Fu B, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID‐19 patients with tocilizumab. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14. Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mehta B, Salmon J, Ibrahim S. Potential shortages of hydroxychloroquine for patients with lupus during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. URL: https://jamanetwork.com/channels/health‐forum/fullarticle/2764607. JAMA Health Forum; 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolfe F, Michaud K. The National Data Bank for rheumatic diseases: a multi‐registry rheumatic disease data bank. Rheumatology 2011;50:16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. Development and validation of the health assessment questionnaire II: a revised version of the health assessment questionnaire. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3296–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wolfe F, Michaud K, Pincus T. A composite disease activity scale for clinical practice, observational studies, and clinical trials: the patient activity scale (PAS/PAS‐II). J Rheumatol 2005;32:2410–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parekh K, Taylor WJ. The patient activity scale‐II is a generic indicator of active disease in patients with rheumatic disorders. J Rheumatol 2010;37:1932–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Evaluating and testing persons for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). 2020. URL: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/hcp/clinical‐criteria.html.

- 21. England BR, Sayles H, Mikuls TR, Johnson DS, Michaud K. Validation of the rheumatic disease comorbidity index. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station (TX): StataCorp; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sbaraini A, Carter SM, Evans RW, Blinkhorn A. How to do a grounded theory study: a worked example of a study of dental practices. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 2017;33:2938–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shaver TS, Anderson JD, Weidensaul DN, Shahouri SS, Busch RE, Mikuls TR, et al. The problem of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity and remission in clinical practice. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1015–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cron RQ, Chatham WW. The rheumatologist's role in COVID‐19. J Rheumatol 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kapoor KM, Kapoor A. Role of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID‐19 infection: a systematic literature review. URL: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.24.20042366v1. medRxiv; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dahly D, Gates S, Morris T. Statistical review of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial: version 1.1. URL: https://zenodo.org/record/3725560#.Xp83O8hKg2w. Zenodo; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Touret F, de Lamballerie X. Of chloroquine and COVID‐19. Antiviral Res 2020;177:104762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yazdany J, Kim AHJ. Use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine during the COVID‐19 pandemic: what every clinician should know. Ann Intern Med 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Owens B. Excitement around hydroxychloroquine for treating COVID‐19 causes challenges for rheumatology. Lancet Rheumatol 2020. E‐pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ruiz‐Irastorza G, Egurbide MV, Pijoan JI, Garmendia M, Villar I, Martinez‐Berriotxoa A, et al. Effect of antimalarials on thrombosis and survival in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2006;15:577–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials