Abstract

We illustrate the progression of Cardiobacterium hominis infective endocarditis in a patient with a bioprosthetic mitral valve and decompensated heart failure secondary to an obstructive septic vegetation.

Keywords: Cardiobacterium hominis, Infective endocarditis, Septic vegetation, Heart failure

Introduction

Cardiobacterium hominis is a fastidious pleomorphic gram-negative bacillus belonging to the HACEK group of microorganisms (Haemophilus species, Aggregatibacter species, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, and Kingella species), accounting for approximately 1–2% of community acquired cases of native valve endocarditis [1]. C. hominis mainly exists as normal oral flora, with a low virulence in causing infective endocarditis (IE), with the exception in patients with a history of valvular disease [2]. The onset of disease is indolent often following dental and endoscopic procedures [2,3].

Case report

A 73-year-old male presented to the emergency department with worsening generalized weakness and unintentional weight loss of 20 pounds for three months. Review of systems was positive for chills, night sweats, and dyspnea on exertion. He was found to be in atrial fibrillation with moderate respiratory distress and hypotension requiring vasopressors. Physical examination was notable for cachexia, poor dentition, bilateral lower extremity edema, and a 4/6 systolic murmur was auscultated over the left sternal border.

Past medical history was notable for hypertension, non-ischemic cardiomyopathy with reduced ejection fraction NYHA II, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation on no anticoagulation due to history of Osler Weber Rendu syndrome, hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (with prior intracranial hemorrhage due to cerebral arteriovenous malformation), and severe mitral regurgitation due to Barlow’s myxomatous degeneration status post failed mitral valve repair in 2006 with complicating ring dehiscence and subsequent bioprosthetic mitral valve replacement in 2013 (33 mm Hancock II). Three months prior to presentation he underwent endoscopic removal of a gastric carcinoid tumor. Additionally, the patient underwent deep dental cleaning six months prior to presentation with antibacterial prophylaxis with oral amoxicillin 2 g.

Initial laboratory workup was notable for a neutrophil predominant leukocytosis (WBC 15,000/μL). Chest radiograph revealed small bilateral pleural effusions and pulmonary edema (Fig. 1). Electrocardiogram demonstrated atrial fibrillation with a heart rate of 100 bpm with nonspecific ST and T wave changes. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed an ejection fraction between 30–35% with severe tricuspid regurgitation and bioprosthetic mitral valve thickening and hemodynamic profile consistent with obstructed valve (Fig. 2, Fig. 3), warranting transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE). The TEE showed infective vegetative material encasing the bioprosthetic leaflets, resulting in mitral valve obstruction (Fig. 4). Blood cultures drawn at admission grew Cardiobacterium hominis after 4 days and speciation after 6 days (Fig. 5).

Fig. 1.

Anteroposterior chest x-ray revealing an enlarged cardiac silhouette, pulmonary edema, small bilateral pleural effusions, and prosthetic mitral valve.

Fig. 2.

Panel A: Transthoracic apical 4 chamber view demonstrating biatrial enlargement, right ventricular dilation, and bioprosthetic mitral valve thickness. Panel B: Magnified imaging of the bioprosthetic mitral valve encased by infective vegetative material. Panel C: Color doppler interrogation of the bioprosthetic mitral valve with turbulent and restrictive flow across the valve.

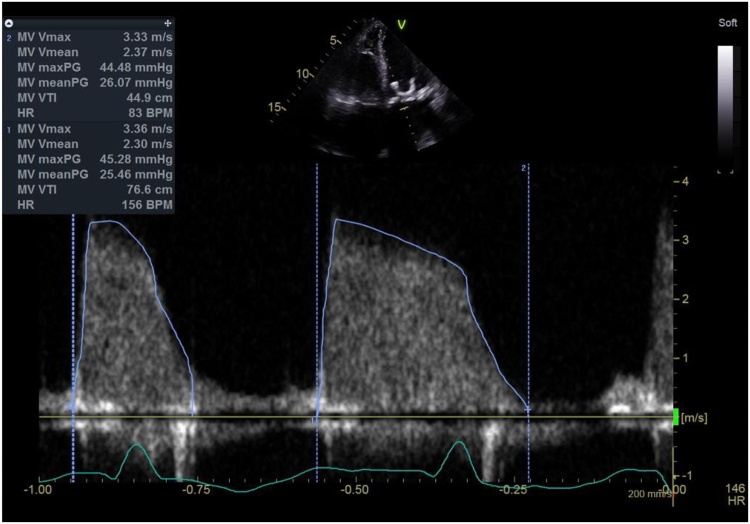

Fig. 3.

Transthoracic apical 4 chamber view with spectral doppler interrogation demonstrating elevated transmittal gradients.

Fig. 4.

Panel A: Transesophageal echocardiogram, mid esophageal 4 chamber view at 60° with magnified view of the left atrium demonstrating significant spontaneous echo contrast. Panel B: 3D-reconstruction demonstrating thickened valve prosthesis and decreased orifice area.

Fig. 5.

Microbiology: Panel A and B revealed no growth on blood and chocolate agar at day 3. Panel C revealed pleomorphic, gram negative bacillus consistent with Cardiobacterium hominis.

The patient was started on empiric antimicrobial therapy with vancomycin and cefepime for presumed prosthetic valve infective endocarditis. The TEE showed infective vegetative material encasing the bioprosthetic leaflets, resulting in mitral valve obstruction. However, the patient was deemed a high-risk candidate for surgery due to his poor functional status and comorbidities. Blood cultures were positive for Cardiobacterium hominis on day four of hospital stay and antimicrobial therapy was deescalated to ceftriaxone.

Discussion

C. hominis, a relatively low virulence organism, has been known to cause infective endocarditis in up to 95% of cases of bacteremia. C. hominis is known to cause large friable vegetations, which are often complicated by heart failure and central nervous system embolism [2]. A previous study reported the most common pre-existing risk factor of C. hominis is cardiac disease (61%), with 28% having a prosthetic valve [4].

Although some guidelines and systematic review do not recommend antibacterial prophylaxis after all dental procedures, it is standard for patients with risk factors for IE and at risk for complications. These risk factors include underlying cardiovascular disease, apparent poor dental hygiene, previous and manipulation of the gingival tissue [5]. Although causing transient bacteremia, guidelines recommend against the use of prophylactic antibacterials during endoscopic procedures, although cases of C. hominis endocarditis after endoscopic procedure have been described [[5], [6], [7]]. Bacterial translocation of microbial flora is postulated to occur secondary to mucosal trauma, related to instrumentation [8]. Procedures that result in dilation of esophageal strictures may have higher predisposition to produce bacteremia [9]. Evidence indicates that rates of bacteremia may be elevated in esophageal and endoscopic procedures involving manipulation of malignant tissue [10]. As demonstrated in this case, our patient received antibacterial prophylaxis with amoxicillin prior to deep cleaning given his medical history. Given the time course between the procedure, it is uncertain if there is a causative relationship between dental procedure and onset of symptoms.

Currently, there exists a paucity of research linking C. hominis infection to endoscopic procedures. Given that patients with esophageal and gastric cancers often possess co-morbidities that place them at higher risks for infective endocarditis and complications associated with IE, it is reasonable to further explore the association between these procedures and IE or offer prophylactic antibacterials to individuals with risk factors for IE such as mitral valve repairs.

Conclusions

Clinicians should be aware of the risk factors for C. hominis especially in patients with bioprosthetic valves. It is reasonable to explore the association between endoscopic procedures and infective endocarditis and consider prophylactic antibiotics.

Funding

None.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Anita Singh- Writing/data collections.

Angel Porras- Writing/data collections.

Francisco Ujueta- Imaging, Saberio Lo Presti- Imaging, Nicholas Camps- Writing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgment

None.

References

- 1.Chambers S.T., Murdoch D., Morris A. HACEK infective endocarditis: characteristics and outcomes from a large, multi-national cohort. PLoS One. 2013;8(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wormser G.P., Bottone E.J. Cardiobacterium hominis: review of microbiologic and clinical features. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5(4):680–691. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.4.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walkty A. Cardiobacterium hominis endocarditis: a case report and review of the literature. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2005;16(5):293–297. doi: 10.1155/2005/716873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malani A.N., Aronoff D.M., Bradley S.F. Cardiobacterium hominis endocarditis: two cases and a review of the literature. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2006;25(9):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s10096-006-0189-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson W., Taubert K.A., Gewitz M. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008:253. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khashab M.A., Chithadi K.V., Acosta R.D. Antibiotic prophylaxis for GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(1):81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pritchard T.M., Foust R.T., Cantely J.R. Prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Cardiobacterium hominis occurring after upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Med. 1991;90(4):516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stephenson P.M., Dorrington L., Harris O.D. Bacteraemia following oesophageal dilatation and oesophago-gastroscopy. Aust N Z J Med. 1977;7(1):32–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1977.tb03353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuccaro G., Jr, Richter J.E., Rice T.W. Viridans streptococcal bacteremia after esophageal stricture dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):568–573. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nelson D.B., Sanderson S.J., Azar M.M. Bacteremia with esophageal dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48(6):563–567. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]