Abstract

Calcium ions bind to lipid membranes containing anionic lipids; however, characterizing the specific ion-lipid interactions in multicomponent membranes has remained challenging because it requires nonperturbative lipid-specific probes. Here, using a combination of isotope-edited infrared spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations, we characterize the effects of a physiologically relevant (2 mM) Ca2+ concentration on zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine and anionic phosphatidylserine lipids in mixed lipid membranes. We show that Ca2+ alters hydrogen bonding between water and lipid headgroups by forming a coordination complex involving the lipid headgroups and water. These interactions distort interfacial water orientations and prevent hydrogen bonding with lipid ester carbonyls. We demonstrate, experimentally, that these effects are more pronounced for the anionic phosphatidylserine lipids than for zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine lipids in the same membrane.

Significance

Phosphatidylserines (PS) play an active role in signaling processes. In some of these roles, proteins recognize and bind PS through bridging calcium ions, but the specific role of the lipid headgroups in mediating these interactions is not understood. Studies using a variety of biophysical techniques have also indicated that interactions between PS and calcium can reshape the structural and mechanical properties of lipid membranes. However, these interactions are not as well characterized in more complex membranes containing multiple lipid components. Here, we have used isotope-edited infrared spectroscopy to nonperturbatively characterize the effect of physiological concentrations of calcium on membranes containing a mixture of PS and the more abundant phosphatidylcholines.

Introduction

Lipid membranes play a central role in a range of physiological processes, including signaling, metabolism, apoptosis, and endocytosis (1, 2, 3). Such diversity of functions is accompanied by structural diversity, and biological membranes are composed of thousands of distinct lipid species, including an array of anionic phospholipids (4,5). Anionic lipids are not just structural components but have been found to actively participate in cell signaling processes (2,6). The ubiquity and importance of anionic lipids have raised interest in characterizing lipid-cation interactions because their binding to certain cations modulates membrane properties (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12) and alters lipid-protein (6,13,14) and lipid-water interactions (15, 16, 17, 18).

Calcium ions preferentially associate with membranes containing phosphatidylserine (PS) lipids, which have a net negative charge from their phosphate, amine, and carboxylate groups (Fig. 1; (19)). Extracellular exposure of PS signals processes such as apoptosis and blood coagulation (20). In PS-containing membranes, Ca2+ binding can alter the spatial organization (10,21, 22, 23, 24) and local curvature (25,26), as well as modulate interactions between lipids and proteins (6,13,14,27). Although PS binds a variety of cations (19,28, 29, 30, 31, 32), we focus on calcium because of its signaling roles and ability to mediate interactions between membranes and proteins (6,13,27). These include proteins such as annexin V that bind to PS directly through a bridging calcium ion (6,27,33). Ca2+ has been shown to alter lipid-water interactions in PS-containing membranes (8,18,34) via fluorescence and infrared spectroscopy, create domains enriched in anionic lipids (24), and high Ca2+ concentrations even induce cigar-shaped “cochleate” structures composed of dehydrated lipids (12,35). The effects of Ca2+ are highly concentration dependent (8), but the impact of physiological Ca2+ concentrations (≤2 mM) (11,36) on PS lipids, particularly when the PS lipids are not the primary membrane component, remains underexplored. Biological membranes are composed of a variety of lipid species, and because zwitterionic phosphatidylcholine (PC) headgroups are the most abundant in eukaryotes (1,37), it becomes essential to understand the effect of ions on individual membrane components.

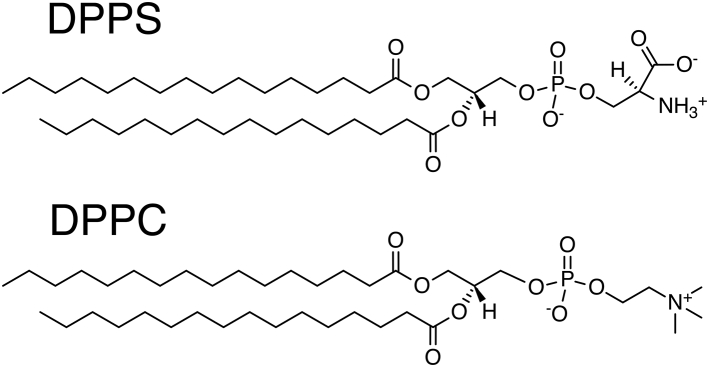

Figure 1.

Structures of DPPS (upper) and DPPC (lower).

In this study, we probe the effects of Ca2+ on hydrogen bonding and hydration around both the zwitterionic and anionic components of a bilayer using infrared spectroscopy of the ester carbonyl stretching modes in combination with atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. We have incorporated [13C] isotope-labels into the carbonyls to isolate the vibrational modes of individual species in the mixtures. Experimental results are in good agreement with MD simulations, enabling us to extract an atomistic picture of the binding configurations.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and sample preparation

Isotope-labeled dipalmitoyl phosphatidylcholine (DPPC (13C)) was synthesized via Steglich esterification following a procedure developed by Ichihara et al. (38). Briefly, 0.1 mmol sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine was dissolved in methanol and adsorbed onto Celite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The solvent was evaporated from the Celite in a vacuum desiccator for 12 h and then combined with two equivalents 1-[13C] palmitic acid and 2.5 equivalents 4-dimethylaminopyridine in a 10-mL round-bottom flask. The solids were suspended in dry chloroform, and five equivalents of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide were added. The suspension was stirred under nitrogen in the dark for 48 h. To remove 4-dimethylaminopyridine and any other cationic impurities, ion exchange resin (DOWEX 50W X8; Sigma-Aldrich) was added and stirred with the reaction mixture for 30 min. The suspension was then filtered to remove dicyclohexylurea, Celite, and the ion exchange resin. Finally, DPPC (13C) was purified via a silica flash column with 65:25:4 CHCl3/MeOH/H2O v/v as the eluent.

Dipalmitoyl phosphatidylserine (DPPS) with Na+ as a counterion and unlabeled DPPC were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL) and used without further purification. The samples were prepared by combining lipids dissolved in chloroform and methanol in appropriate mole ratios. The solvent was removed under a dry stream of nitrogen, followed by mild vacuum for 12 h. Deuterated water (D2O) was then added to suspend the lipids to a concentration of 70 mM. For the Ca2+-containing samples, the contained 2 mM CaCl2 (35 lipids per Ca2+ ion), and for the Ca2+-free samples, the deuterated water contained 1 mM EDTA to complex any traces of divalent cations. To avoid overlap between absorption bands of lipids and water, D2O was used for all infrared spectra. To improve sample homogeneity and reduce scatter, six freeze-thaw cycles were performed followed by ultrasonication for 20 min immediately before infrared (IR) measurements.

Infrared spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy spectra were recorded on a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer. Aqueous suspensions of phospholipid membranes were held between two calcium fluoride windows separated by a 50-μm-thick Teflon spacer. The spectrometer was purged with ultradry air to minimize water vapor absorption. Samples were held at 58 ± 1°C using a temperature-controlled water recirculator to ensure that the bilayers were in the fluid phase. Phase transition temperatures were measured by measuring spectra between 38 and 56°C in 1°C increments, with 3 min of equilibration at each temperature.

Molecular dynamics simulations

Starting conformations of the 1:1 mixture of DPPS and DPPC were generated using the Membrane Builder module (39,40) of CHARMM-GUI (41,42). Each leaflet was composed of 50 DPPC and 50 DPPS lipids. A total of 34.3 water molecules per lipid were placed in the box. Each system was prepared to contain 150 mM NaCl, with an additional 100 Na+ counterions to balance the anionic DPPS lipid charges. Similarly, a system with Ca2+ ions was prepared by the same procedure followed by the removal of 20 random Na+ ions, 10 of which were replaced by Ca2+.

GROMACS (43) (version 2016.3) was used to perform the MD simulations with the CHARMM36 parameters (44,45) with NBFix (46, 47, 48) for the lipids and ions and the CHARMM-modified TIP3P parameters (49) for water. The two bilayer systems were energy minimized using the steepest descent method. After energy minimization, equilibration was performed for 375 ps following the CHARMM Membrane Builder protocol (40,42) in which restraints were gradually relaxed. After equilibration, production simulations were carried out with a timestep of 2 fs using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat (50,51) at 330 K and a semi-isotropic Parrinello-Rahman barostat (52) at 1 bar. Equilibrium was confirmed by the convergence of the area per lipid over time during the 500-ns production run (See Fig. S4). The Parallel Linear Constraint Solver algorithm (53) was used to constrain bond lengths involving hydrogen atoms. The Verlet method (54,55), with a minimal cutoff of 1.2 nm, was used to update the neighbor list for all nonbonded interactions. Electrostatics were calculated using the smooth particle mesh Ewald method (56,57) using cubic interpolation with a grid spacing of 0.12 nm, and real-space cutoff of 1.2 nm. Van der Waals forces were smoothly switched to zero from 1.0 to 1.2 nm (58). The final 300 ns of each NPT 500-ns trajectory were analyzed using the built-in suite of tools in GROMACS.

Results and Discussion

Ester carbonyl spectroscopy

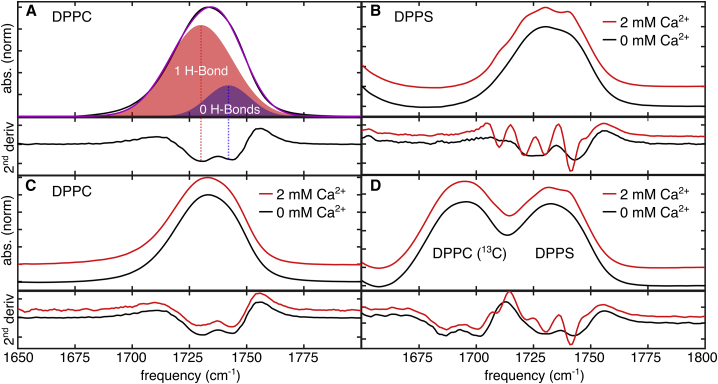

Changes in the packing and hydration of phospholipids are observable through shifts in infrared absorption spectra. Here, we focus primarily on the ester absorption band. Lipid ester carbonyls are located precisely at the ∼1-nm interface between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic regions of the bilayer and are sensitive to lipid packing and interfacial interactions. Additionally, the lipid ester band is composed of multiple peaks, which can be analyzed with second derivative plots and curve fitting, and isotope-edited spectroscopy makes it possible to observe the individual lipids in a mixture. The lipid ester absorption band occurs near 1730 cm−1, as shown in Fig. 2 A. This band is generally composed of two separate peaks, which are split by the presence of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) (29,59). It is well established that in the absence of an H-bond, the carbonyl peak is centered near 1745 cm−1, shifting to 1730 cm−1 upon H-bond formation. Although the two peaks overlap, they can be clearly resolved through their second derivative spectra, as shown in Fig. 2, A–D. Both peaks are well fit to Gaussian functions, and the relative areas of the two peaks, as visualized in Fig. 2 A, are directly proportional to the ratio of hydrogen bonded esters to free esters. PC lipids lack hydrogen bond donors, and water is necessary to mediate H-bonding in these membranes. On the other hand, in PS, the ammonium group can donate H-bonds. However, direct H-bonding between the −NH3+ and ester C = O groups is unlikely given the distance between these two groups. Indeed, no such interactions are observed in our simulations. Therefore, in this study, changes in the ester C = O lineshapes result from changes in the density or orientation of water molecules at the interface.

Figure 2.

Infrared spectra of the ester-stretching band of the lipids studied. In each upper panel is the absorption spectrum, and in each of the lower panel is the second derivative of the absence with respect to the frequency to show peak splitting. (A) Ester-stretching band of DPPC with the corresponding H-bonding component peaks by second derivative analysis and curve fitting is shown. The shaded Gaussians represent the best-fit to these two peaks that make up the band. (B) shows DPPS ester absorption band with and without Ca2+. In the presence of Ca2+, the band splits into four peaks as observed in the second derivative. (C) shows DPPC ester absorption band with and without Ca2+. (D) shows DPPC (13C) and DPPS ester absorption bands from a mixture of the two lipids in which DPPC has been isotope labeled to exhibit an absorption band that does not overlap with the absorption band from DPPS. The −40-cm−1 shift is a result of the change in C = O mass and does not perturb its environment. To see this figure in color, go online.

The splitting of the ester absorption band of anionic lipid membranes has been observed to increase in the presence of metal cations (16,29). Instead of two broad peaks, several narrow peaks are observed. These peaks may be the result of multiple narrow distributions of lipid conformations, which is supported by observations of dynamics near the headgroup (9,60) as well as simulations (10). Both trapped water (61) and dehydration (29) have been proposed as sources for these peaks.

Addition of 2 mM Ca2+ did not affect the lineshape of zwitterionic DPPC alone (Fig. 2 C) as observed by the band lineshape retaining its overall two-peak structure; however, 2 mM Ca2+ significantly altered the splitting for DPPS-only membranes (Fig. 2 B). Instead of two peaks, Ca2+ splits the band into four narrow, distinct peaks, as observed in the second-derivate lineshapes. Previous measurements showed that the presence of Ca2+ induces splitting in PS/PC mixtures but were not able to resolve whether this change was specific to DPPS or if it occurred for both lipids (60), as the negative phosphate and polar ester groups present on DPPC could potentially bind to Ca2+ ions. Here, we investigated the specificity of the cation-lipid interactions in a 1:1 DPPC/DPPS binary mixture using DPPC that has been isotope labeled with [13C] at the ester positions (DPPC (13C)). The 40-cm−1 red shift that results from isotope incorporation separates the DPPC (13C) and DPPS absorption bands, allowing for mapping their environments individually without perturbing the membrane. Spectra (Fig. 2 D) of the mixture only showed changes in splitting for the DPPS lipids as the lineshapes for DPPC (13C) are similar with and without the Ca2+. Therefore, the data show that the effects of Ca2+ were localized to PS and that the environment remained unchanged for PC.

The interpretation of our experimental results is complicated by the fact that the local concentration at the lipid-water interface is significantly higher than the bulk concentration, as the negative charge of DPPS creates a surface potential leading to a greatly increased concentration of cations at the interface when compared with the bulk (62). Previous studies (17,18), have demonstrated that calcium ions dehydrate DPPC membranes at high concentrations. A simple Gouy-Chapman model predicts an ∼−100 mV potential near the interface and indicates that the local Ca2+ at the interface is 1.3 M, and similar potentials are predicted by numerically solving the Poisson-Boltzmann equation using lipid configurations sampled from MD (see Fig. S2), as well as the potential predicted directly from the MD trajectory. These three models have increasing level of detail, with Gouy-Chapman only accounting for the charge density, Poisson-Boltzmann accounting for the roughness of the interface, and, finally, MD including all contributions from ions and water molecules. However, potential alone is not sufficient to accurately predict interfacial concentrations because ions are not point charges. In MD simulations, the predicted interfacial Ca2+ concentration is only ∼0.12 M (Fig. S5), approximately an order of magnitude smaller compared to continuum models. Regardless of the model employed, these simulations predict a higher Ca2+ concentration near the membrane compared to bulk, and therefore, it is important to assess the effect of these ion concentrations on DPPC, as a control, to ensure that the changes observed in DPPS are not due to the increased interfacial concentration alone.

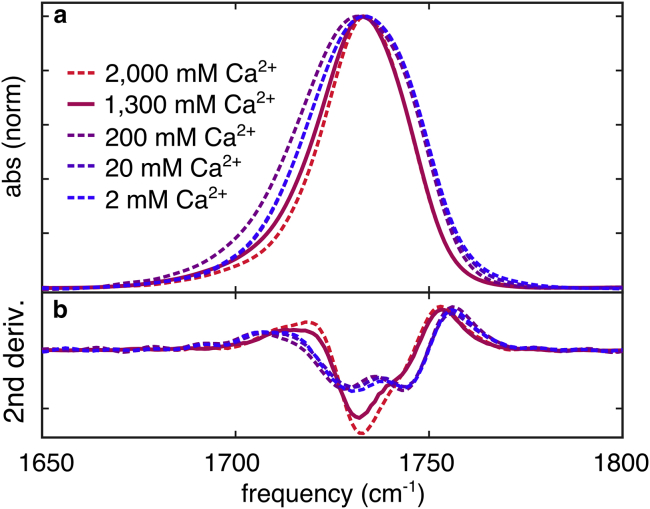

We tested these high calcium concentration effects on DPPC by increasing the bulk concentration by several orders of magnitude. Within highest Ca2+ concentrations (Fig. 3), we observed a transition to a narrowed ester absorption band. Second derivative spectra reveal that this narrow band is primarily composed of a single peak instead of the two peaks observed without high Ca2+. Intermediate calcium concentrations (∼200 mM), shift the ester absorption band to lower frequencies without changing the underlying peak structure, as evidenced by the second derivative lineshape. No change to the DPPC peak was observed in the spectra of the lipid mixture shown in Fig. 2 D. These results suggest that DPPC is not subject a high local Ca2+ concentration, indicating that lateral segregation creates membrane regions with high potential (enriched in PS), and regions with low potential (enriched in PC).

Figure 3.

Infrared spectra of the ester-stretching band of DPPC in the presence of several concentrations of CaCl2 (A) absorption spectra and (B) second derivative spectra. The value of 1.3 M was chosen because this represents the calculated interfacial Ca2+ concentration in the PC/PS mixed membranes (Fig. S6). To see this figure in color, go online.

Molecular dynamics simulations provide an atomistic interpretation of the effect of ions on interfacial hydration. Analysis of MD trajectories showed a binding preference for DPPS in the mixed bilayers. Specifically, radial distribution functions (RDFs) revealed that Ca2+ was more likely to bind phosphate or ester oxygens on DPPS lipids compared to DPPC (see Fig. 4). As a control, MD simulations of DPPC-only membranes were carried out using the same protocol described above. In the 1:1 DPPC/DPPS simulation, Ca2+ density in the bulk water region was essentially zero because of lipid/Ca2+ binding. This was not observed in the pure DPPC simulation (see Fig. S5).

Figure 4.

RDFS of Ca2+ to (A) lipid ester oxygens and (B) lipid phosphate oxygens from a simulation of 1:1 DPPC/DPPS in the presence of Ca2+. To see this figure in color, go online.

The DPPS phosphate RDF (Fig. 4 B) showed significantly higher intensity than the DPPC RDF for all peaks indicating that the local density of Ca2+ ions was higher near PS lipid phosphates, showing preferential binding. Furthermore, an additional peak around 0.65 nm was present in the RDF for PS. Indeed, Table S1 includes an analysis of local contacts around Ca2+ ions, showing strong binding to the carboxylates within PS. These results suggest that Ca2+ interactions with carboxylates indirectly affect the ester carbonyls, which are located ∼0.6 nm further into the hydrophobic region of the bilayer. Because experimental lineshapes report on the local electrostatics, in the next section, we examine how binding affects the H-bonding environment at the ester carbonyl positions.

Simulated effects of Ca2+ on hydrogen bonding

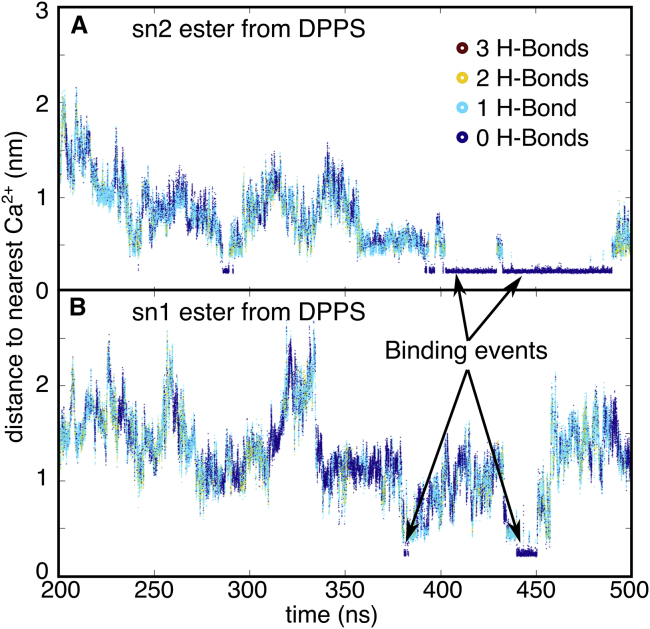

Changes in ester carbonyl IR lineshapes were assigned to altered H-bonding environments at the lipid-water interface near the ester carbonyls. In contrast, global properties such as the gel-to-liquid phase transition temperatures remained unchanged with the addition of Ca2+ (see Figs. S9–S11), suggesting that hydrocarbon tail ordering and packing remain unaffected. Therefore, we focus on H-bonding to the ester carbonyls. To illustrate the effects of Ca2+ on H-bond populations, Fig. 5 shows two example trajectories for sn1 and sn2 DPPS carbonyls. The figure shows that once an ion binds to a lipid (within 0.3 nm), the number of hydrogen bonds is reduced to essentially zero, as evidenced by the regions of the trajectory where the Ca2+-to-C = O distance remains constant. Tables S1 and S2 show that this was observed for all lipid esters that were within one hydration shell of a calcium ion during the simulation. Because an H-bond is a directional interaction, the loss of H-bonds could be the result of either 1) fewer water molecules (i.e., lower density) near the carbonyls or 2) water molecules lacking the proper orientation to form H-bonds. Next, we examine these two contributions independently.

Figure 5.

Hydrogen bond and Ca2+ proximity over time of (A) the sn2 carbonyl from a DPPS molecule in the simulation and (B) the sn1 carbonyl from another DPPS in the simulation. The color of the line reports the number of hydrogen bonds to the lipids, and the vertical axis reports on the distance to the nearest Ca2+ ion. The arrows shows the reduction in H-bond populations when Ca2+ is within 0.3 nm of the lipid. To see this figure in color, go online.

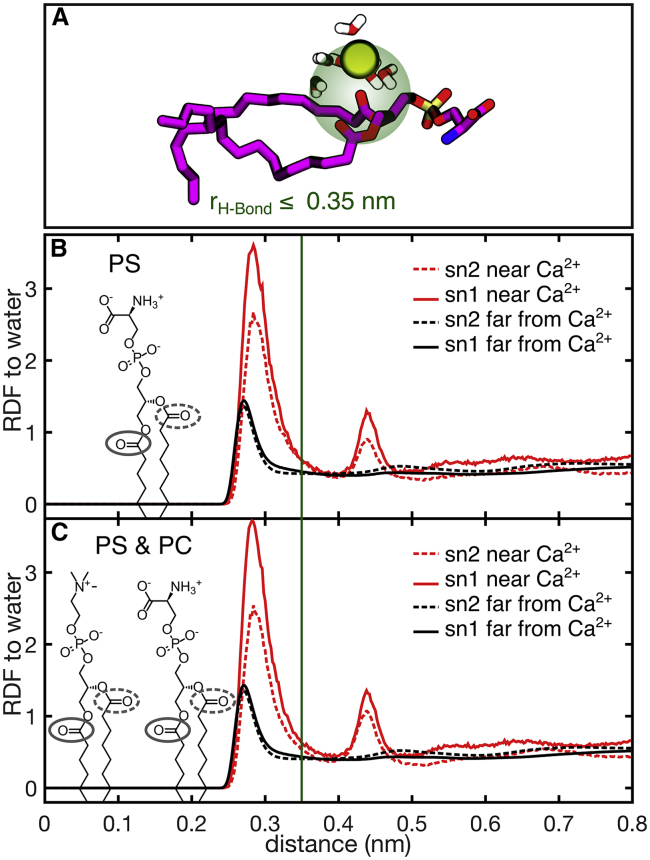

Local water density

To characterize the local density of water molecules around the carbonyls, we examined the RDFs from lipid ester oxygens to water oxygens both for lipid esters that were within one hydration shell (0.3 nm) of Ca2+ and those that were not (Fig. 6, B and C). Surprisingly, the analysis shows that the presence of a nearby Ca2+ ion increases the density of water molecules within the hydrogen bond cutoff radius (0.35 nm), despite the sharp decrease in hydrogen bonds to the lipid esters as shown in Fig. 5. Additionally, we found that the carbonyl-to-water RDFs calculated near Ca2+ (red plots) were characterized by two narrow peaks: the first centered below 0.3 nm and the second around 0.45 nm, whereas carbonyls without nearby Ca2+ (black plots) lack the second peak. Qualitatively, the presence of a second peak indicates that Ca2+ induced ordering of water molecules at the interface. The increased density of water, as well as the increased order of water near Ca2+, can both be understood as consequences of calcium’s hydration shell, which we were able to observe visually from snapshots of the MD trajectory such as in Fig. 6 A. In other words, the ion retains some of its hydration shell when binding PS. This results in an enrichment of ordered water molecules at the interface.

Figure 6.

(A) Example MD snapshot showing the orientations of water near the lipid and Ca2+. (B) shows RDFs from DPPS lipid ester oxygen atoms to water for esters within 0.3 nm of Ca2+, compared to the bulk of the membrane. (C) shows RDFs from DPPS and DPPC lipid ester oxygen atoms to water for esters within 0.3 nm of Ca2+ and in the bulk of the membrane. To see this figure in color, go online.

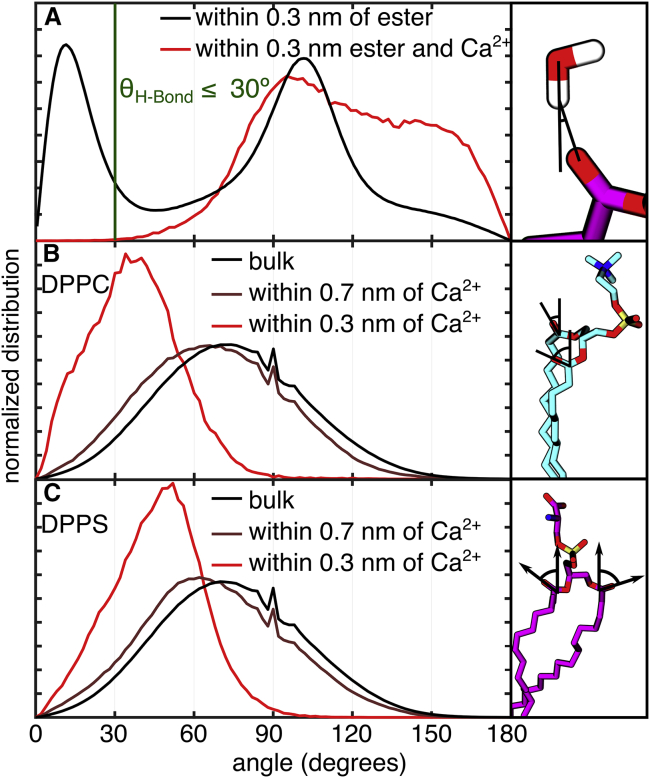

Orientations of local waters

Given that the local water density increases in the presence of Ca2+, the loss of H-bonds must then result from changes in the relative orientations. Namely, the local water molecules must lack favorable orientations to H-bond with the carbonyls. Here, we examine the distributions of donor-hydrogen-acceptor (DHA) angles in which the donor is the oxygen atom in water, and the acceptor is the carbonyl oxygen as shown in Fig. 7 A. Previous studies established a DHA angle and distance cutoffs of <30° and <0.35 nm, respectively, as the geometric criteria for H-bonds, which are now widely used in the literature (43,63). Fig. 7 A shows a large peak in the histogram centered around 11.5°, and water molecules within this ensemble, which contains ∼30% of the total waters, are counted toward the H-bond populations. With a Ca2+ within one hydration shell (0.3 nm), however, the distribution is shifted to wider angles, and as a consequence, the probability of waters with an orientation between 0 and 30° is less than 1%. Therefore, this analysis reveals that less than 1% of water molecules near both an ester group and a Ca2+ form H-bonds with the ester. This is consistent with the existence of an ordered complex around the Ca2+ composed of both lipids and water molecules, as shown in Fig. 6 A.

Figure 7.

(A) Orientations of water molecules near lipid esters relative to the ester locations with and without nearby Ca2+. The cutoff angle for hydrogen bonds is shown as a vertical green line. Orientations of (B) DPPC and (C) DPPS ester carbonyls relative to the membrane normal in the bulk membrane (black), within the intermediate distance of 0.7 nm of Ca2+ (brown), and within the binding cutoff of 0.3 nm (red) are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

The lack of proper DHA orientations in the presence of Ca2+ examined above could result from a combination of 1) water reorganization near the carbonyls and 2) changes in carbonyl orientations. To uncover the primary contribution, we analyzed the orientation of the lipid esters with respect to the bilayer normal. Similar to the previous analyses, we separated lipid esters near Ca2+ from the remaining esters. Further, to obtain more insights into the origin of the observed lineshapes, we analyzed the DPPC and DPPS lipids separately. The results of these analyses are shown in Fig. 7, B and C. We found that Ca2+ results in narrower orientational distributions shifted toward smaller angles (∼50°) between the lipid esters and the bilayer normal. Therefore, the analysis shows that interactions with Ca2+ induce a reorientation of both the carbonyls and water molecules around the calcium ions. Together, the MD results are consistent with our measured spectra, which indicate a disruption of lipid-water hydrogen bonds and a set of narrowly distributed environments around the DPPS ester carbonyls in the presence of Ca2+. Specifically, the highly distorted carbonyl and water angles may explain the presence of blue-shifted peaks in the spectrum where the carbonyls may experience strong electric fields as a result of interactions with the nearby water oxygen atoms. Furthermore, the narrow peaks in the experimental spectrum (Fig. 2, B and D) may be a result of narrowly distributed carbonyl orientations (Fig. 7 C) induced by the presence of a nearby ion. Finally, although simulations show the ions affect both PC and PS, with a binding preference for PS, experimental results indicate that, under the experimental conditions probed, the effects are localized to PS. This does not necessarily indicate that Ca2+ binding to PC does not occur; however, the spectra of DPPC in the presence of high Ca2+ concentrations shown in Fig. 3 indicate that the effects of Ca2+ on the local hydration at the membrane interface are different depending on the presence or absence of DPPS. Previous studies have shown that the miscibility of DPPC and DPPS is reduced in the presence of Ca2+ (21,24,64), and phase separation may explain why the PC spectrum remains unaffected. It is also possible that Ca2+ binds the lipid mixture relatively nonspecifically under the experimental conditions probed but then once bound, it has a larger effect on the interfacial hydration of DPPS than on DPPC. These effects are not mutually exclusive, and more work is required to elucidate local interactions between complicated lipid systems and aqueous ions.

Conclusions

Using isotope-edited infrared spectroscopy, we characterized the effects of Ca2+ at millimolar concentrations on the zwitterionic and anionic components of a mixed lipid membrane. In a 50:50 mixture of DPPC/DPPS, the calcium ions strongly impacted the hydrogen bonding environment near the lipid-water interface, as observed via Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. In contrast, no measurable changes were observed for the zwitterionic lipids in the mixture. We investigated these changes in atomistic detail using MD simulations and found that Ca2+ decreased H-bonding between water and lipids by reorienting lipid and water molecules. The changes in orientation are consistent with the narrow, well-defined peaks observed in the absorption spectra, which may result from specific configurations. Simulations indicate that Ca2+ affects the environment around C = O for both PC and PS, however, because the experiment indicated changes primarily to the DPPS environment. It should be noted that difficulties in simulating lipid-ion interactions have been reported (48,65), and the MD results may be distorted by the difficulties in accurately modeling lipid-ion interactions despite recent improvements such as the NBFix parameters, which were used here (46,47).

The spectroscopic results presented here should provide a benchmark for future simulations, particularly because IR absorption spectra can be directly simulated from MD, using electrostatic frequency maps (66, 67, 68), provided that the MD ensemble is realistic. Furthermore, phase separation, if present, remains challenging to simulate because of the long timescales associated with these processes. As such, we expect isotope-edited IR spectroscopy, as well as ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy (59,69), to serve as a useful benchmark for future MD models.

The findings presented here may be applicable to changes experienced by biological membranes after extracellular exposure of PS, which is a marker for apoptosis and blood coagulation (70,71), as well as a feature of several types of abnormal cells, including sickle cells and some tumor cells (20,72). The interactions characterized in this study will help better understand the biophysical role of anionic lipids in such complex cellular processes.

Author Contributions

M.L.V., A.E.C., R.E., and C.R.B. designed the research. M.L.V. carried out lipid synthesis and experimental measurements. A.E.C. carried out the simulations and analyzed trajectories. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding from the National Science Foundation (BIO-1815354), the National Institutes of Health (GM111364), and the Welch Foundation (F-1891 and F-1896). Molecular dynamics simulations were carried out using the resources of the Texas Advanced Computing Center.

Editor: Sarah Veatch.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.04.013.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Ingólfsson H.I., Melo M.N., Marrink S.J. Lipid organization of the plasma membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lizardo D.Y., Parisi L.R., Atilla-Gokcumen G.E. Noncanonical roles of lipids in different cellular fates. Biochemistry. 2018;57:22–29. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasson P.M., Pande V.S. Control of membrane fusion mechanism by lipid composition: predictions from ensemble molecular dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2007;3:e220. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corradi V., Sejdiu B.I., Tieleman D.P. Emerging diversity in lipid-protein interactions. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:5775–5848. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian H., Sparvero L.J., Winograd N. Secondary-ion mass spectrometry images cardiolipins and phosphatidylethanolamines at the subcellular level. Angew. Chem. Int.Engl. 2019;58:3156–3161. doi: 10.1002/anie.201814256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Swairjo M.A., Concha N.O., Seaton B.A. Ca(2+)-bridging mechanism and phospholipid head group recognition in the membrane-binding protein annexin V. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:968–974. doi: 10.1038/nsb1195-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poyton M.F., Sendecki A.M., Cremer P.S. Cu(2+) binds to phosphatidylethanolamine and increases oxidation in lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1584–1590. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b11561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melcrová A., Pokorna S., Cwiklik L. The complex nature of calcium cation interactions with phospholipid bilayers. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:38035. doi: 10.1038/srep38035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boettcher J.M., Davis-Harrison R.L., Rienstra C.M. Atomic view of calcium-induced clustering of phosphatidylserine in mixed lipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2264–2273. doi: 10.1021/bi1013694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallock M.J., Greenwood A.I., Pogorelov T.V. Calcium-induced lipid nanocluster structures: sculpturing of the plasma membrane. Biochemistry. 2018;57:6897–6905. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mokkila S., Postila P.A., Róg T. Calcium assists dopamine release by preventing aggregation on the inner leaflet of presynaptic vesicles. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:1242–1250. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.6b00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilschut J., Düzgüneş N., Papahadjopoulos D. Modulation of membrane fusion by membrane fluidity: temperature dependence of divalent cation induced fusion of phosphatidylserine vesicles. Biochemistry. 1985;24:8–14. doi: 10.1021/bi00322a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lakomek N.-A., Yavuz H., Pérez-Lara Á. Structural dynamics and transient lipid binding of synaptobrevin-2 tune SNARE assembly and membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:8699–8708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813194116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Z., Jiang X., Li C. Calcium accelerates SNARE-mediated lipid mixing through modulating α-synuclein membrane interaction. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:1848–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Binder H., Arnold K., Zschörnig O. Interaction of Zn2+ with phospholipid membranes. Biophys. Chem. 2001;90:57–74. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bornemann S., Herzog M., Winter R. Impact of Y3+-ions on the structure and phase behavior of phospholipid model membranes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019;21:5730–5743. doi: 10.1039/c8cp07413e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanti De S., Kanwa N., Chakraborty A. Spectroscopic evidence for hydration and dehydration of lipid bilayers upon interaction with metal ions: a new physical insight. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:14796–14807. doi: 10.1039/c8cp01774c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binder H., Zschörnig O. The effect of metal cations on the phase behavior and hydration characteristics of phospholipid membranes. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2002;115:39–61. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monson C.F., Cong X., Cremer P.S. Phosphatidylserine reversibly binds Cu2+ with extremely high affinity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7773–7779. doi: 10.1021/ja212138e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zwaal R.F.A., Comfurius P., Bevers E.M. Surface exposure of phosphatidylserine in pathological cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:971–988. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4527-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kouaouci R., Silvius J.R., Pézolet M. Calcium-induced lateral phase separations in phosphatidylcholine-phosphatidic acid mixtures. A Raman spectroscopic study. Biochemistry. 1985;24:7132–7140. doi: 10.1021/bi00346a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schultz Z.D., Pazos I.M., Levin I.W. Magnesium-induced lipid bilayer microdomain reorganizations: implications for membrane fusion. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:9932–9941. doi: 10.1021/jp9011944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ross M., Steinem C., Janshoff A. Visualization of chemical and physical properties of calcium-induced domains in DPPC/DPPS Langmuir−Blodgett layers. Langmuir. 2001;17:2437–2445. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui S.W., Boni L.T., Isac T. Identification of phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylcholine in calcium-induced phase separated domains. Biochemistry. 1983;22:3511–3516. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali Doosti B., Pezeshkian W., Lobovkina T. Membrane tubulation in lipid vesicles triggered by the local application of calcium ions. Langmuir. 2017;33:11010–11017. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magarkar A., Jurkiewicz P., Jungwirth P. Increased binding of calcium ions at positively curved phospholipid membranes. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2017;8:518–523. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang M., Rigby A.C., Furie B.C. Structural basis of membrane binding by Gla domains of vitamin K-dependent proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003;10:751–756. doi: 10.1038/nsb971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martín-Molina A., Rodríguez-Beas C., Faraudo J. Effect of calcium and magnesium on phosphatidylserine membranes: experiments and all-atomic simulations. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2095–2103. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hübner W., Blume A. Interactions at the lipid–water interface. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 1998;96:99–123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roux M., Bloom M. Ca2+, Mg2+, Li+, Na+, and K+ distributions in the headgroup region of binary membranes of phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylserine as seen by deuterium NMR. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7077–7089. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ermakov Y.A., Kamaraju K., Sukharev S. High-affinity interactions of beryllium(2+) with phosphatidylserine result in a cross-linking effect reducing surface recognition of the lipid. Biochemistry. 2017;56:5457–5470. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassanin M., Kerek E., Prenner E.J. Binding affinity of inorganic mercury and cadmium to biomimetic erythrocyte membranes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2016;120:12872–12882. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b10366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodríguez Y., Mezei M., Osman R. The PT1-Ca2+ Gla domain binds to a membrane through two dipalmitoylphosphatidylserines. A computational study. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13267–13278. doi: 10.1021/bi801199v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roux M., Bloom M. Calcium binding by phosphatidylserine headgroups. Deuterium NMR study. Biophys. J. 1991;60:38–44. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82028-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawar A., Bothiraja C., Mali A. An insight into cochleates, a potential drug delivery system. RSC Adv. 2015;5:81188–81202. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu N., Francis M., Stevens T. Studies on the resolution of subcellular free calcium concentrations: a technological advance. Focus on “detection of differentially regulated subsarcolemmal calcium signals activated by vasoactive agonists in rat pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells”. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2014;306:C636–C638. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00046.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marsh D. Second Edition. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL: 2013. Handbook of Lipid Bilayers. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ichihara K., Iwasaki H., Tomosugi M. Synthesis of phosphatidylcholine: an improved method without using the cadmium chloride complex of sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2005;137:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jo S., Lim J.B., Im W. CHARMM-GUI membrane builder for mixed bilayers and its application to yeast membranes. Biophys. J. 2009;97:50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu E.L., Cheng X., Im W. CHARMM-GUI membrane builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2014;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jo S., Kim T., Im W. CHARMM-GUI: a web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee J., Cheng X., Im W. CHARMM-GUI input generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, openMM, and CHARMM/openMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klauda J.B., Venable R.M., Pastor R.W. Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beglov D., Roux B. Finite representation of an infinite bulk system: solvent boundary potential for computer simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 1994;100:9050–9063. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venable R.M., Luo Y., Pastor R.W. Simulations of anionic lipid membranes: development of interaction-specific ion parameters and validation using NMR data. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2013;117:10183–10192. doi: 10.1021/jp401512z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S., Patel D.S., Im W. Bilayer properties of lipid A from various gram-negative bacteria. Biophys. J. 2016;111:1750–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Antila H., Buslaev P., Piggot T.J. Headgroup structure and cation binding in phosphatidylserine lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2019;123:9066–9079. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b06091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Durell S.R., Brooks B.R., Ben-Naim A. Solvent-induced forces between two hydrophilic groups. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:2198–2202. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoover W.G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A Gen. Phys. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nosé S., Klein M.L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics for molecular systems. Mol. Phys. 2006;50:1055–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hess B. P-LINCS: a parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:116–122. doi: 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verlet L. Computer “experiments” on classical fluids. I. Thermodynamical properties of Lennard-Jones molecules. Phys. Rev. 1967;159:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Páll S., Hess B. A flexible algorithm for calculating pair interactions on SIMD architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013;184:2641–2650. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an N⋅log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steinbach P.J., Brooks B.R. New spherical-cutoff methods for long-range forces in macromolecular simulation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994;15:667–683. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stevenson P., Tokmakoff A. Ultrafast fluctuations of high amplitude electric fields in lipid membranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:4743–4752. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valentine M.L., Cardenas A.E., Baiz C.R. Physiological calcium concentrations slow dynamics at the lipid-water interface. Biophys. J. 2018;115:1541–1551. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.08.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Casal H.L., Mantsch H.H., Hauser H. Infrared and 31P-NMR studies of the interaction of Mg2+ with phosphatidylserines: effect of hydrocarbon chain unsaturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;982:228–236. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sinn C.G., Antonietti M., Dimova R. Binding of calcium to phosphatidylcholine–phosphatidylserine membranes. Colloids Surf. Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2006;282–283:410–419. [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Spoel D., van Maaren P.J., Tîmneanu N. Thermodynamics of hydrogen bonding in hydrophilic and hydrophobic media. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:4393–4398. doi: 10.1021/jp0572535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Onishi S., Ito T. Calcium-induced phase separations in phosphatidylserine--phosphatidylcholine membranes. Biochemistry. 1974;13:881–887. doi: 10.1021/bi00702a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Melcr J., Martinez-Seara H., Ollila O.H.S. Accurate binding of sodium and calcium to a POPC bilayer by effective inclusion of electronic polarization. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2018;122:4546–4557. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b12510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi J.-H., Lee H., Cho M. Computational spectroscopy of ubiquitin: comparison between theory and experiments. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:045102. doi: 10.1063/1.2424711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edington S.C., Flanagan J.C., Baiz C.R. An empirical IR frequency map for ester C=O stretching vibrations. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2016;120:3888–3896. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b02887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fried S.D., Bagchi S., Boxer S.G. Measuring electrostatic fields in both hydrogen-bonding and non-hydrogen-bonding environments using carbonyl vibrational probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11181–11192. doi: 10.1021/ja403917z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Volkov V.V., Nuti F., Righini R. Hydration and hydrogen bonding of carbonyls in dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine bilayer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9466–9471. doi: 10.1021/ja0614621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Leventis P.A., Grinstein S. The distribution and function of phosphatidylserine in cellular membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2010;39:407–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fadok V.A., Voelker D.R., Henson P.M. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J. Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sapar M.L., Ji H., Han C. Phosphatidylserine externalization results from and causes neurite degeneration in Drosophila. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2273–2286. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.07.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.