Summary

Steroid hormones modulate development, reproduction and communication in eukaryotes. The widespread occurrence and persistence of steroid hormones have attracted public attention due to their endocrine‐disrupting effects on both wildlife and human beings. Bacteria are responsible for mineralizing steroids from the biosphere. Aerobic degradation of steroid hormones relies on O2 as a co‐substrate of oxygenases to activate and to cleave the recalcitrant steroidal core ring. To date, two oxygen‐dependent degradation pathways – the 9,10‐seco pathway for androgens and the 4,5‐seco pathways for oestrogens – have been characterized. Under anaerobic conditions, denitrifying bacteria adopt the 2,3‐seco pathway to degrade different steroid structures. Recent meta‐omics revealed that microorganisms able to degrade steroids are highly diverse and ubiquitous in different ecosystems. This review also summarizes culture‐independent approaches using the characteristic metabolites and catabolic genes to monitor steroid biodegradation in various ecosystems.

Aerobic degradation of steroid hormones relies on O2 as a co‐substrate of oxygenases to activate and to cleave the recalcitrant steroidal core ring. To date, two oxygen‐dependent degradation pathways—the 9,10‐seco pathway for androgens and the 4,5‐seco pathways for estrogens—have been characterized. Under anaerobic conditions, denitrifying bacteria adopt the 2,3‐seco pathway to degrade different steroid structures.

Introduction

Thus far, more than 1000 different steroids are found to naturally occur (Haubrick and Assmann, 2006; Hannich et al., 2011; Valitova et al., 2016; Zubair et al., 2016; Staley et al., 2017; Stonik and Stonik, 2018), including commonly distributed sterols (e.g. cholesterol, phytosterols and ergosterol), steroid hormones (e.g. 17β‐oestradiol, progesterone and testosterone) and bile acids (e.g. cholic acid) (see Fig. 1 for the common steroid structures). A remarkable characteristic of steroids is their extremely low aqueous solubility; that is, cholesterol has a maximum solubility of 4.7 μM (= 1.8 mg l−1) in aqueous solutions (Haberland and Reynolds, 1973). The aqueous solubility of steroid hormones is also extremely low; for example, in neutral aqueous solutions, the solubility of natural oestrogens [e.g. oestrone (E1) and 17β‐oestradiol (E2)] is approximately 1.5 mg l−1 at room temperature (Shareef et al., 2006), whereas the experimental aqueous solubility of testosterone can reach 23 mg l−1 at 25°C (Barry and El Eini, 1976). Similarly, the synthetic 17α‐ethynyloestradiol (EE2) also has a low solubility in water (4.8 mg l−1 at 20°C) (Aris et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

The chemical structures of prevalent natural and synthetic steroid hormones. The ring identification (A‐D) and carbon numbering (1‐27) systems for steroids are shown on cholesterol. Underlined compounds are synthetic steroids.

In animals, cholesterol is the precursor of all classes of steroid hormones, namely glucocorticoids, mineralocorticoids and sex hormones (androgens, oestrogens and progestogens). The biosynthesis of steroid hormones involves the elimination of the cholesterol side chain and hydroxylation of the steroid nucleus (Ghayee and Auchus, 2007). All these hydroxylation reactions require NADPH and molecular oxygen; thus, steroid biosynthesis only occurs in the aerobic biosphere. Among sex steroids, progestogens (such as protesterone) function in preparing the lining of the uterus for implantation of an ovum and are also essential for maintaining pregnancy. The biotransformation of progesterone into androgens includes a hydroxylation at C‐17 and the subsequent cleavage of the side chain. Androgens regulate the development and maintenance of male characteristics in vertebrates, and the major androgens naturally produced in males are testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and androstenedione (also named androst‐4‐en‐3,17‐dione, AD) (see Fig. 1 for structures) (O’Connor et al., 2011). Oestrogens are responsible for developing and regulating the reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics of female vertebrates. Major endogenous oestrogens in females include E1, E2 and estriol (E3) (see Fig. 1 for structures). Oestrogens are synthesized from androgens by the loss of the C‐19 angular methyl group and the formation of an aromatic A‐ring. The aromatization proceeds with three consecutive oxidative steps (Miyairi and Fishman, 1985). Aromatase (namely P450arom or CYP19) catalyses the sequential hydroxylations of a C19 substrate using three molecules of NADPH and three molecules of molecular oxygen to produce one molecule of oestrogen (Praporski et al., 2009).

Numerous steroids are used for medical purposes, such as in treatments for cancer, arthritis and allergies, as well as birth control (Woutersz, 1991; Peter et al., 1994; Merz et al., 2010; Dokras, 2016). A variety of synthetic hormones are commonly used as medications for humans as well as livestock and aquaculture. Synthetic androgens (anabolic steroids) are ester derivatives of androgens known as 19‐nortestosterone or nandrolone (see Fig. 1 for structures) are often used to treat anemias, cachexia, osteoporosis and breast cancer. EE2 is a synthetic oestrogen widely used in oral contraceptives in combination with progestin, a synthetic progestogen (Wise et al., 2011). EE2 is also used to improve productivity by promoting growth and preventing and treating reproductive disorders in livestock (Liu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018). In aquaculture, EE2 is often used to develop single‐sex populations of fishes to optimize growth (Aris et al., 2014).

The impact, occurrence and fates of steroid sex hormones in environments

Steroid sex hormones are pheromones and endocrine disruptors

Some steroid hormones are noted as pheromones in animals, including fish, amphibians and mammals (Doyle and Meeks, 2018). Studies on fish olfactory systems indicated that most fishes use steroids for chemical communication (Moore and Scott, 1991; Baza´es and Schmachtenberg, 2012). Sulphated steroids (e.g. 17β‐oestradiol disulphate) are potent olfactory chemosignals in larval amphibians (Houck, 2009). Androstenone, 17β‐oestradiol disulphate, estratetraenol and testosterone sulphate are considered sex pheromones in some mammals, such as mice and pigs (Doyle and Meeks, 2018). As pheromones, steroids can affect fish behaviour in a variety of ways, even at extremely low concentrations (Adams et al., 1987; Kolodziej et al., 2003; Kolodziej et al., 2004; Serrano et al., 2008).

The potential for sex hormones to disrupt endocrine functions in various organisms via direct or indirect exposure has been extensively investigated (Aris et al., 2014). Several studies showed that oestrogens cause endocrine disruption in fishes (Jobling et al., 2006; Morthorst et al., 2014), frogs (Lambert et al., 2015; Regnault et al., 2018) and invertebrates (Oetken et al., 2004). Notably, both natural and synthetic oestrogens displayed endocrine‐disrupting activities at concentrations as low as nanograms per litre (Robinson and Hellou, 2009). The potencies of these oestrogens are measured in relation to E2 (set at 100) – EE2: 246; E1: 2.54; and E3: 17.6 (Pillon et al., 2005). On the other hand, some studies have reported that exposure to androgens in polluted rivers leads to the masculinization of freshwater wildlife (Howell et al., 1980; Bortone et al., 1989; Parks et al., 2001; Orlando et al., 2004). In addition, the endocrine‐disrupting effects of synthetic progestogens on aquatic species have been documented (Zeilinger et al., 2009; Cardoso et al., 2017).

Potential sources of steroid hormones in environments

Steroid sex hormones may originate from agriculture, industry, humans, household products and other pharmaceuticals (Wise et al., 2011). Human excreta have been considered a major source of steroid hormones in aquatic environments (Johnson et al., 2000; Chang et al., 2011). Livestock also excrete large amounts of sex steroids into the environment (Maier et al., 2000; Lange et al., 2002). Manure used as fertilizers has also been a major source of steroid hormones released into the environment (Hanselman et al., 2003; Kjaer et al., 2007). Steroid hormones can also end up in aquatic ecosystems via rainfalls and leaching from livestock wastes (Hanselman et al., 2003; Kolodziej et al., 2004). In addition, steroid hormones can be discharged into environments through agricultural applications of municipal sewage biosolids as fertilizers (Lorenzen et al., 2004; Hamid and Eskicioglu, 2012). Moreover, steroid hormones in the environment may partially be the result of microbial activities (Mendelski et al., 2019). For example, phytosterols in pulp and paper mill effluents can be transformed into androgens by microorganisms in river sediments (Jenkins et al., 2003; Orrego et al., 2009).

Environmental levels of steroid sex hormones

Global urbanization has led to the widespread occurrence of steroid hormones becoming a concern worldwide. Both biogenic (natural) and anthropogenic steroid hormones are frequently detected in soils and aquatic environments in the United Kingdom, United States, Japan, Korea, Denmark, Spain, Taiwan, France, China, Swaziland, Czech Republic and Slovak Republic (Belfroid et al., 1999; Ternes et al., 1999; Baronti et al., 2000; Hashimoto et al., 2000; Huang and Sedlak, 2001; Kolodziej et al., 2003; Shore and Shemesh, 2003; Labadie and Budzinski, 2005; Bjerregaard et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007; , 2007; Fan et al., 2011; Vajda et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Wise et al., 2011; Orlando and Ellestad, 2014; Gorga et al., 2015; Shih et al., 2017; Šauer et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhang and Fent, 2018). In surface water, the concentration of steroid hormones ranges from nanograms to micrograms per litre (Ternes et al., 1999; Baronti et al., 2000; Kolodziej et al., 2003; Labadie and Budzinski, 2005; Yamamoto et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2010; Chang et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2011; Šauer et al., 2018; Shen et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhang and Fent, 2018). For example, oestrogens, androgens, progestogens, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids were detected in the surface water of urban rivers in Beijing (China), with androgens (0.48–1.9 µg l−1) being the most abundant (Chang et al., 2009). In addition, concentrations of natural oestrogens (E1, E2 and E3) in the Wulo Creek of southern Taiwan were as high as 1.3 µg l−1 due to the livestock feedlot nearby (Chen et al., 2010). The content of steroid hormones in river and marine sediments is often detected at ng g−1 levels (Huang et al., 2013; Gorga et al., 2015; Praveena et al., 2016; Tiwari et al., 2016).

Fate of steroid sex hormones in engineered and natural ecosystems

Sex hormones can be removed or transformed by engineered ecosystems such as activated sludge in wastewater treatment plants (Andersen et al., 2003; Chang et al., 2009; Yu and Chu, 2009; Chang et al., 2011; Fan et al., 2011), constructed wetlands (Song et al., 2009), microalgae systems (Lai et al., 2002; Solé and Matamoros, 2016), sludge‐amended soils (Albero et al., 2013), swine manure, poultry litter, dairy waste disposal systems and compost (Hutchins et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2015). Wastewater treatment plants are crucial for removing steroid hormones via physical adsorption and biodegradation, although the latter is considered the major mechanism (Joss et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2013). Chang et al. (2011) investigated the removal of androgens, oestrogens and progestogens in seven wastewater treatment plants. Their study indicated a high removal efficiency (91–100%) for androgens and progestogens; however, the removal efficiency for oestrogens was relatively lower (67–80%).

The removal of steroid hormones through microbial activities is also observed in natural ecosystems such as soils (Fan et al., 2007; Mashtare et al., 2013), river water (Jürgens et al., 2002), sandy aquifers (Ying et al., 2003), as well as seawater and marine sediments (Homklin et al., 2011; Gorga et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2015a). In general, microorganisms degrade steroids slowly under oxygen‐limited or oxygen‐fluctuating conditions. Thus, anaerobic environments such as river and marine sediments are reservoirs for steroids (Mackenzie et al., 1982; Hanselman et al., 2003; Czajka and Londry, 2006).

Microorganisms involved in the degradation of steroid sex hormones

Steroids are carbon‐rich and highly reduced compounds that are abundant and ubiquitous in the environment; thus, they are attractive carbon and energy sources for microorganisms. Certain microorganisms, including bacteria (Fernandes et al., 2003; Donova and Egorova, 2012), yeasts (Liu et al., 2017), fungi (Kristan and Rižner, 2012) and microalgae (Pollio et al., 1994), are able to transform steroids, but the ability to mineralize steroids (complete degradation of steroids to CO2) has only been identified in certain bacteria (Bergstrand et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016; Holert et al., 2018). The major focus of recent research has been elucidating the diversity of steroid degraders and their degradation mechanisms. Several studies have used culture‐dependent approaches to isolate steroid hormone‐degrading bacteria from different engineered and natural ecosystems, and diverse degraders classified as actinobacteria and proteobacteria have been reported (Bergstrand et al., 2016). The significance of investigating steroid‐microorganism interactions has increased for four main reasons. First, microbial degradation is crucial for removing steroid sex hormones from polluted ecosystems. Second, microbial transformation of steroids has been exploited in the pharmaceutical industry to produce high‐value steroid drugs through biotechnology processes. Third, steroid degradation is important for the virulence of some bacterial pathogens. Fourth, recent studies suggest that steroid hormones mediate bidirectional interactions between bacteria and their eukaryotic hosts (vom Steeg and Klein, 2017). In this review, we summarize the important steroid hormone‐degrading bacteria.

Aerobic steroid hormone‐degrading bacteria

Talalay et al. (1952) were the first to isolate an unidentified Gram‐negative bacterium from soils capable of growing on an agar plate containing testosterone as the sole carbon source. This bacterium – reclassified as Comamonas testosteroni DSM 50244 (Betaproteobacteria) (Tamaoka et al., 1987) – was able to degrade testosterone completely, according to a stoichiometry ratio of testosterone, O2 and CO2. Later, another betaproteobacterium isolated from soils, Alcaligenes sp. strain M21, was shown to be capable of growing on testosterone or E2 as its sole carbon source (Payne and Talalay, 1985). Thus far, C. testosteroni strains ATCC 11996 and TA441 have been the model microorganism for studying the testosterone catabolic pathway (Zhang et al., 2011; Horinouchi et al., 2012). Interestingly, some testosterone‐degrading proteobacterial isolates originated from marine environments (Zhang et al., 2011; Sang et al., 2012); for example, Endozoicomonas montiporae BCRC 17933, a gammaproteobacterium isolated from the encrusting pore coral Montipora aequituberculata (Yang et al., 2010), is capable of using testosterone as sole carbon source (Ding et al., 2016). In addition to the proteobacteria (Horinouchi et al., 2012), most other testosterone‐degrading bacteria belong to the phylum Actinobacteria (Bergstrand et al., 2016). Among them, R. ruber DSM 43338, R. aetherivorans DSM 44752 and R. rhodochrous DSM 43269 can only grow on a single type of steroid hormone (testosterone), whereas R. ruber strain Chol‐4 (= DSM 45280) displayed a broad range of catabolic capacities for cholesterol, testosterone and progesterone (Fernández de las Heras et al., 2009). This strain and R. rhodochrous DSM 43269 have been used to identify degradation genes responsible for different steroid substrates in actinobacteria (Petrusma et al., 2009, 2011, 2014; Fernández de las Heras et al., 2012; Fernández de Las Heras et al., 2013; Guevara et al., 2017). On the other hand, information on progesterone degraders is relatively scant. Apart from the above‐mentioned R. ruber strain Chol‐4, only a few studies have reported transformation of progesterone via certain kinds of bacteria (Donova, 2007; Donova and Egorova, 2012).

The complete microbial degradation of oestrogens was first described by Coombe et al. (1966) in the actinobacterium Nocardia sp. E 110, isolated from soil. Some Rhodococcus isolates from soil or activated sludge (e.g. R. equi and R. zopfii) were capable of degrading oestrogens completely (Yoshimoto et al., 2004; Kurisu et al., 2010). On the other hand, the oestrogen‐degrading alphaproteobacterial Novosphingobium tardaugens NBRC 16725 (Fujii et al., 2003) and Sphingomonas spp. (Ke et al., 2007; Yu et al., 2007) were isolated and characterized, and the mechanisms involved in the oestrogen catabolism have been identified recently (Chen et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019). A list of the bacterial strains capable of aerobic steroid degradation is given in Table 1. To our knowledge, no microorganisms are able to utilize the synthetic oestrogen EE2 as sole carbon and energy source. However, strains R. equi ATCC 13557 and R. erythropolis ATCC 4277 displayed partial EE2 degradation activity when co‐incubated with glucose and adipic acid, respectively (O’Grady et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Selection of the bacterial strains capable of aerobic degradation of steroid hormones.

| Phylum/class | Strain | Origin | Genome information | Steroid substrates | Growth on agar plate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G + C content (mol%) | Accession number | |||||

| Actinobacteria | Rhodococcus ruber M1,N361 (DSM 43338) | Activated sludge | 70.5 | GCF_001646835.1 | AD, cholesterol, testosterone | Yes |

| Rhodococcus aetherivorans 10BC‐312 (DSM 44752) | Activated sludge | NA | NA | AD, ADD, testosterone | Yes | |

| Rhodococcus ruber Chol‐4 | Activated sludge | 70.6 | GCF_000347955.2 | AD, ADD, cholesterol, 17β‐Oestradiol, testosterone, progesterone | Yes | |

| Amycolatopsis sp. 75iv2 (ATCC 39116) | Soil | 69.1 | AFWY00000000 | Cholesterol, testosterone | Yes | |

| Rhodococcus equi ATCC 13557 | NA | NA | NA | 17α‐Ethinyloestradiol (partial degradation) | Yes | |

| Rhodococcus erythropolis ATCC 4277 | Soil | 67.0 | NA | 17α‐Ethinyloestradiol (partial degradation) | Yes | |

| Alphaproteobacteria | Novosphingobium tardaugens ARI‐1 (NBRC 16725) | Activated sludge | 61.2 | CP034719 | 17β‐Oestradiol, oestrone, estriol | Yes |

| Sphingomonas sp. KC8 | Activated sludge | 63.7 | CP016306 | 17β‐Oestradiol, oestrone, testosterone | Yes | |

| Sphingomonas wittchii RW1 | River | 68.4 | CP000699 | Testosterone | Yes | |

| Betaproteobacteria | Comamonas testosterone (ATCC 11996, DSM 50244) | Soil | 61.5 | AHIL00000000.1 | Testosterone | Yes |

| Cupriavidus necator H16 (ATCC17699) | Activated sludge | 66.5 | NC_008313 | Testosterone | No | |

| 66.7 | NC_008314 | |||||

| Gammaproteobacteria | Endozoicomona montiporae CL‐33 (BCRC 17933) | Coral | 48.4 | CP013251 | Testosterone | Yes |

| Pseudomonas resinovorans CA10 (NBRC 106553) | Activated sludge | 65.6 | AP013068 | Testosterone | NA | |

AD, androst‐4‐en‐3,17‐dione; ADD, androsta‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione; NA, not available.

Anaerobic steroid hormone‐degrading bacteria

The aerobic steroid degraders have been extensively isolated; by contrast, the number of anaerobic steroid‐degrading bacterial isolates is relatively limited. The complete degradation (mineralization) of steroids in sediments under denitrifying conditions was first reported by Taylor et al (1981). To date, only a few anaerobic steroid‐degrading bacteria have been isolated and characterized (Harder and Probian, 1997; Fahrbach et al., 2008). Sterolibacterium denitrificans strain Chol‐1S (= DSM 13999), isolated from denitrifying sludge in a wastewater treatment plant (Tarlera and Denner, 2003), is able to grow with various sterols (Warnke et al., 2017) and androgens (Wang et al., 2014), with nitrate as the terminal electron acceptor. A denitrifying betaproteobacterium, Denitratisoma oestradiolicum strain AcBE2‐1 (= DSM 16959), is able to degrade natural oestrogens (E1 and E2) but not cholesterol or androgens (Fahrbach et al., 2006). However, a closely related strain, Denitratisoma sp. DHT3, isolated from denitrifying sludge in a wastewater treatment plant, had the capacity to degrade E1, E2 and testosterone (Wang et al., 2019). Based on the stoichiometric analysis, the above‐mentioned bacterial isolates were shown to completely degrade specific steroids. Interestingly, these steroid hormone‐degrading anaerobes share common physiological traits. First, colony growth on an agar plate was very marginal or not observed; thus, their isolation and purification were conducted via repeating serial dilution. Second, all strains utilized an extremely narrow spectrum of substrates. Third, they are able to use either oxygen or nitrate as the electron acceptor, but D. oestradiolicum AcBE2‐1 cannot degrade E2 with oxygen as the electron acceptor (Fahrbach et al., 2006). The betaproteobacterium Thauera terpenica strain 58Eu (= DSM 12139), isolated from a ditch (Foss and Harder, 1998), is able to degrade testosterone, but the presence of the co‐substrate (acetate) in denitrifying medium is essential (Yang et al., 2016). Recently, Azoarcus sp. strain Aa7 capable of degrading ADD under denitrifying conditions has been isolated from soil (Yücel et al., 2019). The bacterial strains capable of anaerobic steroid degradation are shown in Table 2. Notably, all these denitrifiers are facultative anaerobes and can be handled easily under aerobic conditions. Moreover, the genomes of most of these strains are available.

Table 2.

Characterized bacterial strains that are capable of degrading steroid hormones under anaerobic conditions.

| Class | Strain | Origin | Genome information | Steroid substrates | Electron acceptors (growth with steroids) | Growth on agar plate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G + C content (mol%) | Accession number | ||||||

| Betaproteobacteria | Azoarcus sp. Aa7 (DSM 16959) | Soil | 66.1 | QVLR00000000 | ADD, cholate, deoxycholate | Nitrate | Yes |

| Denitratisoma oestradiolicum AcBE2‐1 (DSM 16959) | Activated sludge | 61.4 | NCXS00000000 | E1, E2 | Nitrate | Marginal | |

| Denitratisoma sp. DHT3 | Activated sludge | 64.9 | CP020914 | E1, E2, testosterone | Nitrate | No | |

| Sterolibacterium denitrificans Chol‐1S (DSM 13999) | Activated sludge | 65.3 | LT837804 | AD, cholesterol, testosterone | Nitrate, oxygen | No | |

| Sterolibacterium sp. 72Chol (DSM 12783) | Ditch | NA | NA | Cholesterol | Nitrate, oxygen | Nob | |

| Thauera terpenica 58Eu (DSM 12139) | Ditch | 64.2 | ATJV01000070 | Testosteronea | Nitrate | Yes | |

|

Thauera terpenica GDN1 |

Estuarine sediment | NA | NA | Testosteronea | Nitrate | Yes | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | Steroidobacter denitrificans FS (DSM 18526) | Activated sludge | 61.7 | CP011971 | AD, E1, E2, testosterone | Nitrate, oxygen | No |

Bacterial degradation pathways of steroid sex hormones

Aerobic biodegradation of androgens through the 9,10‐seco pathway

The aerobic catabolic pathways for major classes of steroids – including sterols, androgens, oestrogens, progestogens and bile acids – have been elucidated in various bacteria. The cholesterol degradation pathway in actinobacteria has been studied in some details, partially resulting from the biotechnological applications of actinobacteria in steroid drug production (Fernandes et al., 2003; Donova and Egorova, 2012). Moreover, cholesterol catabolism plays a critical role in mycobacterial pathogenicity (Pandey and Sassetti, 2008; VanderVen et al., 2015; Crowe et al., 2017; 2018). Kieslich (1985) was the first to propose a general scheme of aerobic cholesterol degradation, with some common androgens – including AD and androsta‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione (ADD) – as key intermediates in this pathway. The degradation involved a series of enzymes that have been mainly investigated by Dr. Lindsay D. Eltis’ team. The genomic analysis revealed that, in Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, a gene cluster with over 80 catabolic genes is responsible for the cholesterol catabolic pathway (van der Geize et al., 2007; Crowe et al., 2015). Moreover, the key enzymes involved in this pathway, including the oxygenases for the degradation of cholesterol side chain (Rosłoniec et al., 2009; Ouellet et al., 2010) and oxygenolytic cleavage of the A/B‐rings (Yam et al., 2009; Capyk et al., 2011), as well as the hydrolases for the C/D‐rings degradation (Crowe et al., 2017), have been characterized. This aerobic pathway is widely distributed in actinobacteria (Bergstrand et al., 2016), suggesting that aerobic steroid degradation is crucial for their survival in environments. Some actinobacteria can also utilize androgens; one may thus envisage that actinobacteria use homologous enzymes to aerobically degrade androgens through a highly similar pathway (Donova, 2007; Bergstrand et al., 2016).

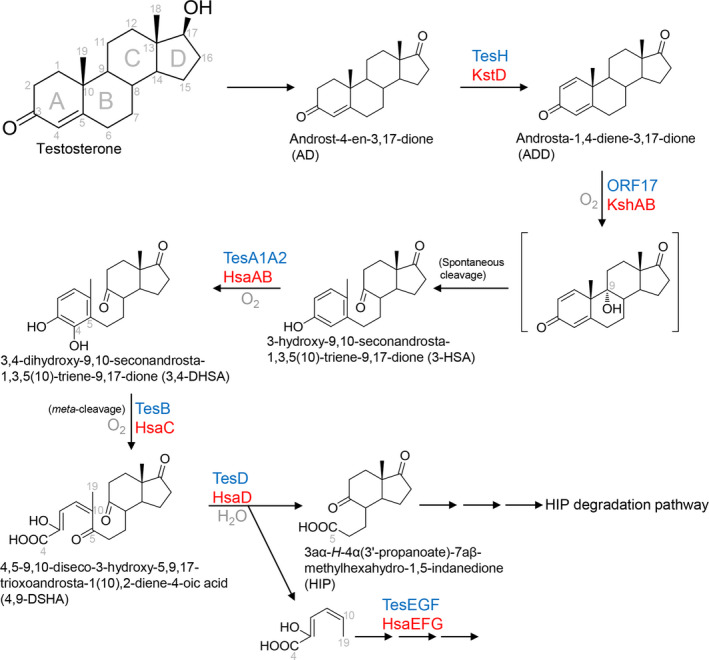

Aerobic androgen degradation has been mainly studied using Comamonas testosteroni (a betaproteobacterium) as the model organism. The studies on aerobic testosterone catabolism were initiated in the 1960s by Sih et al. (1966), and 30 years later, Horinouchi et al. (2001, 2003 Horinouchi et al., 2004) used a gene disruption technique to identify the degradation genes as well as catabolic intermediates accumulated in C. testosteroni mutants. The aerobic degradation pathway of androgens was established based on these molecular studies (Horinouchi et al., 2012; Horinouchi et al., 2018). Under aerobic conditions, C. testosteroni tends to oxidize the 17‐hydroxyl group of testosterone into a carbonyl group. However, this dehydrogenation reaction is not a prerequisite for core ring cleavage. In contrast, oxidation of the A‐ring is thought to initiate the core ring degradation. The process includes two reactions: oxidation of the 3‐hydroxyl moiety and oxidation of C‐1/C‐2 of androgens (Fig. 2). 3α‐ or 3β‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases, members of short‐chain dehydrogenase/reductase family, are involved in the oxidation of 3‐hydroxyandrogens such as epiandrosterone, whereas 3‐ketosteroid‐∆1‐dehydrogenase (TesH) is responsible for the introduction of a double bond between C‐1 and C‐2 of AD. The formation of the 3‐oxo‐1,4‐diene structure at an early stage is critical since it enables cleavage of the core ring. The subsequent step is the hydroxylation at C‐9 in the B‐ring by a monooxygenase, 3‐ketosteroid 9α‐hydroxylase (encoding by orf17). The resulting structure, 9α‐hydroxy‐androsta‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione, is very unstable and undergoes an abiotic cleavage between C‐9 and C‐10 in the B‐ring and the simultaneous aromatization of the A‐ring, producing a secosteroid, 3‐hydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione (3‐HSA). This 9,10‐secosteroid is the key intermediate in this aerobic pathway, named the 9,10‐seco pathway by Philipp (2011). After the production of 3,4‐dihydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrost‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione (3,4‐DHSA) through the 4‐hydroxylation reaction by another monooxygenase – TesA1/A2 – the catecholic A‐ring is subject to meta‐cleavage by an extradiol dioxygenase, TesB. Subsequently, the hydrolase TesD mediates the hydrolytic cleavage between the C‐5 and C‐10 of 4,5‐9,10‐diseco‐3‐hydroxy‐5,9,17‐trioxoandrosta‐1(10),2‐diene‐4‐oic acid (4,9‐DSHA), producing 3aα‐H‐4α(3'‐propanoate)‐7aβ‐methylhexahydro‐1,5‐indanedione (HIP). Overall, the aerobic degradation of the A/B‐rings of androgens requires at least two monooxygenases and an extradiol dioxygenase, with molecular oxygen as a co‐substrate (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The aerobic 9,10‐seco pathway for bacterial degradation of androgens. Characterized or annotated enzymes from proteobacteria are marked in blue, and those from actinobacteria are marked in red. Protein nomenclature is based on that of Comamonas testosteroni strain TA441, Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv, and Rhodococcus jostii strain RHA1. The structure in the bracket (9α‐hydroxy‐androsta‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione) is very unstable and has never been detected. Highly similar pathways were proposed for the aerobic degradation of cholic acid (Holert et al., 2014) and cholesterol (Bergstrand et al., 2016).

One the other hand, the regulation of the androgen degradation genes has been reported. In C. testosteroni, the gene product of teiR (a testosterone‐inducible regulator) positively regulates the transcription of genes involved in the initial steps of steroid degradation (Horinouchi et al., 2004). Pruneda‐Paz et al (2004) further demonstrated that the teiR‐disrupted mutant strain lost the ability to use testosterone as its sole carbon source. By contrast, the repressor protein TetR may be specifically responsible for the expression of the 3β,17β‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase gene (Pan et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2015).

Thus far, bacterial steroid uptake is poorly understood. Actinobacteria transport cholesterol via the ATP‐dependent MCE4 protein, a member of the Mammalian Cell Entry (MCE) superfamily that locates in cytoplasmic membrane (Casali and Riley, 2007; Mohn et al., 2008). In Gram‐negative proteobacteria, the outer membrane and periplasmic space complicate steroid uptake and catabolism. Furthermore, the lipopolysaccharide leaflet on the outer surface of the outer membrane impedes steroids from passive diffusion through the membrane bilayer (Plésiat and Nikaido, 1992). The ATP‐dependent MCE proteins are ubiquitous among proteobacteria (Casali and Riley, 2007). These proteins form a conserved hexameric ring module spanning the periplasmic space to transport phospholipids and other hydrophobic molecules (Malinverni and Silhavy, 2009; Ekiert et al., 2017). Thus, the possibility that MCE‐like transporter might play a role in steroid uptake in proteobacteria cannot be excluded.

Literature on aerobic biodegradation of progestogen is relatively limited. Liu et al. (2013) identified some androgens (e.g. AD and ADD) as intermediates of aerobic progesterone degradation. Moreover, Horinouchi et al. (2012) suggested that C. testosteroni degrades progesterone through the 9,10‐seco pathway. The 9,10‐seco pathway is also responsible for the bile acid degradation in Pseudomonas sp. strain Chol1 (Philipp, 2011). Interestingly, the strain Chol1 accumulated extracellular androgenic intermediates such as ADD during the degradation of bile acids (Holert et al., 2014). The unusual release of the androgens by the bile acid‐degrading bacteria into the environment may have hormonal effects on the coexisting fauna (Mendelski et al., 2019). In summary, the aerobic catabolic pathways of sterols, bile acid, androgens and progestogens proceed through the oxygen‐dependent 9,10‐seco pathway, with 9,10‐secosteroids (e.g. 3‐HSA and its 17‐hydroxyl structure) as characteristic intermediates.

Aerobic degradation of oestrogens through the 4,5‐seco pathway

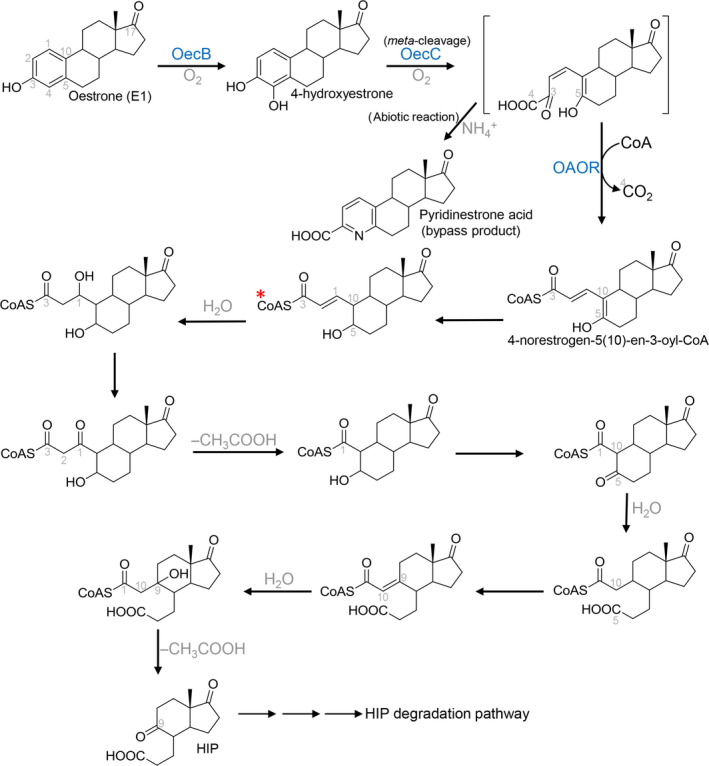

Oestrogens are the most concerning endocrine disruptors (Ghayee and Auchus, 2007) and are also potential carcinogens (Yager and Davidson, 2006). A complete aerobic pathway of oestrogen degradation was recently proposed in the alphaproteobacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain KC8 (Wu et al., 2019), and several gene clusters involved in this aerobic pathway have also been identified (Chen et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2019). Compared to the aerobic 9,10‐seco degradation pathway, the oestrogen degradation pathway is different in several aspects: (i) the core ring cleavage occurs between C‐4 and C‐5 in the A‐ring; thus, the pathway is named the 4,5‐seco pathway; (ii) the A/B‐rings degradation contains a series of coenzyme A (CoA)‐esters; and (iii) this pathway produces oestrogen‐derived dead‐end‐products: pyridinestrone acid (PEA) and 4‐norestrogenic acid (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The aerobic 4,5‐seco pathway for bacterial degradation of natural oestrogens. Characterized or annotated enzymes from proteobacteria are marked in blue. Protein nomenclature is based on that of Sphingomonas sp. strain KC8. *, the deconjugated structure, 4‐norestrogenic acid, is often detected in extracellular environments.

Under aerobic conditions, E2 is first oxidized to E1 by 17β‐oestradiol dehydrogenase (OecA). The C‐4 of E1 is then hydroxylated by a monooxygenase oestrone 4‐hydroxylase (OecB), and the resulting catecholic A‐ring is opened through meta‐cleavage by an extradiol dioxygenase, 4‐hydroxyestrone 4,5‐dioxygenase (OecC) (Fig. 3). The meta‐cleavage product of 4‐hydroxyestrone is unstable, and in the presence of ammonium may undergo an abiotic recyclization to produce a nitrogen‐containing compound pyridinestrone acid. It is known that meta‐ cleavage metabolites produced in bacterial cultures are often abiotically recyclized with ammonium to generate picolinic acid (pyridine 2‐carboxylic acid) products (Dagley et al., 1960; Mycroft et al., 2015). The production of steroid metabolites through non‐enzymatic reactions has also been demonstrated in the 9,10‐seco pathway (Kieslich, 1985). The addition of a hydroxyl group at C‐9 of ADD results in the formation of an unstable 9α‐hydroxylated intermediate, which undergoes a spontaneous split of the B‐ring and then generates the 3‐HSA for further A‐ring degradation. By contrast, once pyridinestrone acid is produced in bacterial cells, it is not able to be further degraded and is excreted into the extracellular environment. Pyridinestrone acid is thus a dead‐end‐product of the 4,5‐seco pathway.

Only a minor part (approximately 2% in the oestrogen‐grown strain KC8 cultures) of the meta‐cleavage product is abiotically transformed into pyridinestrone acid, and the majority (> 95%) of the meta‐cleavage molecules is further degraded by the strain KC8. A member of the indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase family, 2‐oxoacid oxidoreductase (OAOR), removes the C‐4 and adds a CoA to the carboxylic C‐3 of the meta‐cleavage product, producing 4‐norestrogen‐5(10)‐en‐3‐oyl‐CoA through oxidative decarboxylation (Fig. 3). This CoA‐ester has been identified using mass spectrometry and its non‐CoA moiety – 4‐norestrogenic acid – has been structurally determined through NMR spectroscopic analyses (Wu et al., 2019). The deconjugated structure, 4‐norestrogenic acid, is often detected in the extracellular environment. Subsequently, the C‐2 and C‐3 are removed through a cycle of thiolytic β‐oxidation, and the B‐ring is opened through hydrolysis (Fig. 3). A similar hydrolytic ring cleavage mechanism has been demonstrated in the degradation of cyclohexanecarboxylic acid by the alphaproteobacterium Rhodopseudomonas palustris (Pelletier and Harwood, 1998; 2000). Subsequently, the removal of C‐1 and C‐10 through aldolytic cleavage results in the production of HIP. Except for 4‐norestrogen‐5(10)‐en‐3‐oyl‐CoA, no other CoA esters proposed in this aerobic pathway have been detected; however, at least five deconjugated (non‐CoA) metabolites corresponding to these hypothetical CoA esters have been detected in the bacterial cultures (Wu et al., 2019). The dead‐end‐products pyridinestrone acid and 4‐norestrogenic acid are less biodegradable and tend to accumulate in bacterial cultures (Wu et al., 2019) or environmental samples (Chen et al., 2017, 2018); thus, these compounds may serve as biomarkers for investigating environmental aerobic oestrogen biodegradation.

In addition to strain KC8, most metabolites involved in the 4,5‐seco pathway were also identified in another oestrogen degrader, Novosphingobium sp. strain SLCC (Chen et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2019). Initial metabolites, such as 4‐hydroxyestrone and the meta‐cleavage product, were also identified in Sphingomonas sp. strain ED8 (Kurisu et al., 2010) and an actinobacterium Nocardia sp. strain E110 (Coombe et al., 1966). Accordingly, it is speculated that these aerobes may adopt the 4,5‐seco pathway for oestrogen degradation. Although the gene cluster for the oestrogen A/B‐rings degradation has been identified, only three catabolic genes – oecA, oecB and oecC – have been functionally characterized (Chen et al., 2017). The actual role of other genes, 2‐oxoacid oxidoreductase (OAOR), for example, remains to be validated.

Anaerobic degradation of steroids through the 2,3‐seco pathway

Compared to the extensive study (more than 50 years) of the aerobic 9,10‐seco pathway, investigations of anaerobic androgen degradation are relatively recent and limited. The anaerobic 2,3‐seco pathway was first proposed in the testosterone‐degrading gammaproteobacterium S. denitrificans DSM 18526 after the discovery of the ring‐cleavage product 17‐hydroxy‐1‐oxo‐2,3‐secoandrostan‐3‐oic acid (2,3‐SAOA) (Wang et al., 2013), although some metabolites (1‐dehydrotestosterone, 1‐testosterone, AD, ADD and 1‐hydroxysteroids) involved in the initial steps of testosterone transformation were identified prior to this study (Chiang et al., 2010; Leu et al., 2011). This 2,3‐secosteroid, along with other initial metabolites, was also identified in the denitrifying betaproteobacterium S. denitrificans DSM 13999 cultivated with testosterone (Wang et al., 2014).

Thus far, only a few enzymes involved in the 2,3‐seco pathway have been characterized from the strains DSM 13999 and DSM 18526. Some redox enzymes, such as 17β‐hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and 3‐ketosteroid Δ1‐dehydrogenase (AcmB), catalyse the transformation of testosterone into 1‐dehydrotestosterone, AD and ADD (Chiang et al., 2008a; Chiang et al., 2008b; Lin et al., 2015). The same sets of enzymes are also responsible for the redox reactions of androgens under aerobic conditions (Yang et al., 2016). The molybdoenzyme 1‐testosterone hydratase/dehydrogenase (AtcABC) mediates the hydration reaction at the C‐1 of 3‐oxo‐1‐en structures – which includes 1‐testosterone – as well as the subsequent oxidation of the 1‐hydroxyl group (Yang et al., 2016). A phylogenetic analysis of AtcABC sequences suggested that this heterotrimeric protein belongs to the xanthine oxidase family containing molybdopterin, FAD and iron–sulphur clusters. The formation of the 1,3‐dioxo structure in the A‐ring is critical since it enables cleavage of the steroidal core ring (Fig. 4). The hydrolase responsible for the A‐ring cleavage has not been characterized, partially due to the lack of a commercially available substrate (17β‐hydroxy‐androstan‐1,3‐dione or androstan‐1,3,17‐trione). Subsequently, the C‐3 and C‐4 of the cleaved A‐ring are then removed from the secosteroids through a putative aldolytic cleavage (Wang et al., 2014), producing 17β‐hydroxy‐2,5‐seco‐3,4‐dinorandrost‐1,5‐dione (2,5‐SDAD) (Fig. 4). The following B‐ring degradation remains completely unclear; however, the downstream metabolites HIP and HIP‐CoA have been identified as intermediates in the anaerobic androgen degradation pathway (Warnke et al., 2017).

Figure 4.

The anaerobic pathways for bacterial degradation of androgens and oestrogens. Protein nomenclature is based on that of Sterolibacterium denitrficans DSM 13999, Steroidobacter denitrificans DSM 18526 and Denitratisoma sp. strain DHT3. AdoHcy, S‐adenosylhomocysteine; SAM, S‐Adenosylmethionine.

The mechanisms and enzymes involved in anaerobic oestrogen degradation remain poorly studied, although some anaerobic proteobacterial degraders have been isolated. It is very likely that anaerobic bacteria must adopt an oxygen‐independent pathway different from the 4,5‐seco pathway to degrade phenolic A‐ring of oestrogen. Recently, a comparative genomic analysis indicated that certain gene homologues shared in the genomes of S. denitrificans DSM 18526 and two Denitratisoma strains might play a role in anaerobic oestrogen degradation (Chen et al., 2019). Wang et al. (2019) used the Denitratisoma sp. DHT3 as a model organism to identify initial steps of the anaerobic degradation pathway for E2. Their study suggested that denitrifying degraders utilize a convergent catabolic pathway – the 2,3‐seco pathway – to catabolize different steroid structures.

The HIP degradation pathway, a common central pathway for bacterial degradation of the steroid C,D‐rings

It is interesting that HIP – a C13 metabolite with the remaining steroid C/D‐rings – is a common intermediate identified in all bacterial steroid catabolic pathways (the aerobic 9,10‐seco and the 4,5‐seco pathways, as well as the anaerobic 2,3‐seco pathway). The HIP degradation pathway has been mainly established in aerobic actinobacteria, activated by a specific acyl‐CoA synthetase FadD3 (Casabon et al., 2013), although this activation enzyme was also characterized in anaerobic S. denitrificans DSM 13999 (Warnke et al., 2018). The remaining carbons of the steroid B‐ring are then removed through a cycle of thiolytic β‐oxidation. Subsequently, the hydrolytic cleavage of the steroid D‐ring is mediated by an enoyl‐CoA hydratase (EchA20), whereas the C‐ring cleavage is mediated by another hydrolase IpdAB (Crowe et al., 2017; 2018) (Fig. 5A). Surprisingly, the homologues of these ring‐cleavage enzymes were identified in the genomes of aerobic C. testosteroni (Horinouchi et al., 2012; Crowe et al., 2017) and Sphingomonas sp. KC8 (Chen et al., 2017), as well as anaerobic S. denitrificans DSM 13999 (Warnke et al., 2017), Sdo denitficians, and T. terpenica (Yang et al., 2016) (Table 3). Further gene mining showed that most experimentally verified steroid‐degrading bacteria contain gene clusters involved in the HIP degradation pathway (Fig. 5B). These data thus indicate that bacteria adopt divergent pathways to degrade the steroidal A/B‐rings, depending on oxygen conditions and steroid structures. However, all these steroid catabolic pathways then converge at the HIP, and bacteria use the same set of enzymes to degrade the remaining steroid C/D‐rings.

Figure 5.

The HIP degradation pathway shared by all of the studied steroid‐degrading bacteria. (A) The proposed HIP degradation pathway. Characterized or annotated enzymes from proteobacteria are marked in blue, and those from actinobacteria are marked in red. (B) The gene cluster for HIP degradation is widely present in steroid‐degrading actinobacteria and proteobacteria. The evolutionary history was inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequences using the maximum‐likelihood method in MEGA 7 (Kumar et al., 2016). Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 re‐samplings. Bacterial strains marked in black indicate that the aerobic steroid degradation capabilities were physiologically confirmed. Bacterial strains in red are steroid‐degrading denitrifiers. The steroid degradation capabilities of bacteria marked in grey remain to be experimentally confirmed. Gene nomenclature is based on that of Comamonas testosteroni strain TA441 (ORF1 ~ 33) and Mycobacterium tuberculosis strain H37Rv. Orthologous genes are marked with the same colours.

Table 3.

Homologues involved in HIP degradation in steroid‐degrading bacteria.

| Steroid hormone degraders | Enoyl‐CoA hydratase (Ech A20) |

Hydrolase α subunit (IdpA) |

Hydrolase β subunit (IdpB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic actinobacteria | |||

| R. jostii RHA1 | WP_007300903.1 | WP_011597005.1 | WP_011597004.1 |

| M. tuberculosis H37Rv | NP_218067.1 | NP_218068.1 | NP_218069.1 |

| M. smegmatis Mc2‐155 | YP_890227.1 | YP_890228.1 | YP_890229.1 |

| Aerobic alphaproteobacteria | |||

| Sphingomonas sp. KC8 | ARS25885.1 | ARS25890.1 | ARS25889.1 |

| N. tardaugens NBRC 16725 | WP_021688816.1 | WP_021688820.1 | WP_021688819.1 |

| Altererythrobacter sp. MH‐B5 | WP_067540119.1 | WP_067540155.1 | WP_067540130.1 |

| Aerobic betaproteobacteria | |||

| C. testosterone ATCC 11996 | WP_003078394.1 | WP_003078407.1 | WP_003078404.1 |

| C. testosteroni CNB‐2 | ACY32026.1 | ACY32022.1 | ACY32023.1 |

| Denitrifying betaproteobacteria | |||

| S. denitrificans DSM 13999 | SMB21421.1 | SMB21413.1 | SMB21414.1 |

| D. oestradiolicum DSM 16959 | TWO82302.1 | TWO81338.1 | TWO80907.1 |

| Denitratisoma sp. DHT3 | QDX80568.1 | QDX82838.1 | QDX80569.1 |

| T. trepenica 58Eu | WP_021250107.1 | WP_021250110.1 | WP_021250109.1 |

| Denitrifying gammaproteobacteria | |||

| S. denitrificans DSM18526 | WP_066917844.1 | WP_016491273.1 | WP_066917840.1 |

Culture‐independent approaches expand insight into the diversity of sex hormone degraders and ecological significance

Early microcosm and mesocosm studies suggested that oestrogens and testosterone can be biodegraded to CO2 in river sediments (Jürgens et al., 2002), marine sediments (Ying et al., 2003), agricultural soils (Fan et al., 2007) and activated sludges (Andersen et al., 2003) under aerobic or anaerobic conditions. Czajka and Londry (2006) investigated the anaerobic degradation of natural and synthetic oestrogens in lake sediments under methanogenic as well as sulphate‐, iron‐ and nitrate‐reducing conditions, showing that natural oestrogens were degraded under all tested conditions, whereas synthetic EE2 was not apparently degraded by microorganisms. In addition, anaerobic biotransformation of testosterone into oestrogens, including E1 and E2, in testosterone‐spiked estuarine sediment samples under fermentative condition was observed (Shih et al., 2017). These reports suggested that various anaerobes might play a role in steroid hormone degradation in oxygen‐limited environments. However, microbial profiles and functional genes involved in these bioprocesses were lacking. Due to the certain extent of genes and metabolites involved in microbial catabolism of testosterone and oestrogens (Tables 3, 4, 5), recent culture‐independent studies have focused on using this information to discover the signatures of microbial degraders and their degradation activities regarding these sex hormones in different environments.

Table 4.

Selected catabolic genes as biomarkers for identification of the three major steroid degradation pathways.

| Enzyme | Substrate | Product | Gene name & protein ID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 9,10‐seco pathway | C. testosteroni DSM 50244 | C. testosteroni CNB‐2 |

R. ruber Chol‐4 |

R. rhodochrous DSM 43269 |

R. jostii RHA1 |

M. tuberculosis H37Rv | ||

|

3‐Ketosteroid 9α‐hydoxylase (reductase subunit) |

ADD | 3‐HSA |

ORF17 |

ORF17 |

KshA2 |

KshA2 |

KshA WP_050787406.1 |

KshA |

| 3,4‐Dihydroxy‐9,10‐secoandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione‐4,5‐dioxygenase | 3,4‐DHSA | 4,9‐DSHA |

TesB |

TesB |

HsaC |

NA |

HsaC |

HsaC |

| 4,5‐9,10‐Deseco‐3‐hydroxy‐5,9,17‐trioxoandrosta‐1(10),2‐diene‐4‐oate hydrolase | 4,9‐DSHA | HIP |

TesD |

TesD |

HsaD |

NA |

HsaD |

HsaD |

| The 2,3‐seco pathway |

S. denitrificans DSM 13999 |

D. oestradiolicum DSM 16959 |

Denitratisoma sp. DHT3 |

T. terpenica 58Eu |

S. denitrificans DSM 18526 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1‐Testosterone hydratase/dehydrogenase (subunit A) | 1‐Testosterone | 17‐Hydroxy‐and‐rostan‐1,3‐dione |

AtcA |

AtcA |

AtcA |

AtcA |

AtcA |

| The 4,5‐seco pathway |

Sphingomonas sp. KC8 |

N. tardaugens NBRC 16725 |

Altererythrobacter sp. MH‐B5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4‐Hydroxyestrone 4,5‐Dioxygenase | 4‐Hydroxyesterone | Meta‐cleavage producta |

OecC |

OecC |

OecC |

| 2‐Oxoacid oxidoreductase | Meta‐cleavage producta | 4‐Norestrogen‐5(10)‐en‐3‐oyl‐CoA |

OAOR |

OAOR |

OAOR |

ADD, androsra‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione; 3‐HSA, 3‐hydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrost‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione; 4,9‐DSHA: 4,5‐9, 10‐diseco‐3‐hydroxy‐5,9,17‐trioxoandrosta‐1(10),2‐diene‐4‐oic acid; HIP: 3aα‐H‐4α (3’‐propanoate)‐7αβ‐methylhexhydro‐1,5‐indanedione.

See Figure 3 for the chemical structure of the meta‐cleavage product.

Table 5.

UPLC‐HRMS information of characteristic metabolites involved in bacterial degradation of steroid hormones.

| Compound ID | Chemical structure |

UPLC behaviour (RT, min) |

Molecular formula/(predicted molecular mass)c | Dominant ion peaks | Identification of product ions | Mode observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic 9,10‐seco pathway | ||||||

| 3,17‐Dihydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9‐one (3,17‐DHSA) |

|

5.53a |

C19H26O3 302.1881 |

267.1740 285.1844 303.1946 325.1766 |

[M‐2H2O + H]+ [M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

| 3‐Hydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione (3‐HSA) |

|

5.35a |

C19H24O3 300.1725 |

283.1667 301.1801 323.1625 |

[M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

| Aerobic 4,5‐seco pathway | ||||||

| Pyridinestrone acid (PEA) |

|

4.02b |

C18H21O3N 299.1521 |

282.17 300.16 322.15 |

[M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI ESI and APCI ESI |

| 4‐Norestrogenic acid |

|

5.92b |

C17H24O4 292.1675 |

257.15 275.16 293.17 315.16 |

[M‐2H2O + H]+ [M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

| Anaerobic 2,3‐seco pathway | ||||||

| 17‐Hydroxy‐1‐oxo‐2,3‐secoandrostan‐3‐oic acid (2,3‐SAOA) |

|

5.08a |

C19H30O4 322.2144 |

305.21 323.22 345.20 |

[M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

| 1,17‐Dioxo‐2,3‐secoandrostan‐3‐oic acid (DSAO) |

|

5.00a |

C19H28O4 320.1988 |

303.20 321.21 343.19 |

[M‐H2O + H]+ [M + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

| The central HIP degradation pathway | ||||||

| 3aα‐H‐4α(3'‐propanoate)‐7aβ‐methylhexahydro‐1,5‐indanedione (HIP) |

|

2.39a 3.78b |

C17H26O4 294.1831 |

259.17 277.18 317.17 |

[M‐2H2O + H]+ [M‐H2O + H]+ [M + Na]+ |

ESI and APCI ESI and APCI ESI |

RT, retention time.

The UPLC separation was achieved on a reversed‐phase C18 column (Acquity UPLC® BEH C18; 1.7 μm; 100 × 2.1 mm; Waters) with a flow rate of 0.4 ml min−1 at 35°C (column oven temperature). The mobile phase comprised a mixture of two solvents: solvent A [2% (vol/vol) acetonitrile containing 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid] and solvent B [methanol containing 0.1% (vol/vol) formic acid]. Condition 1: separation was achieved using a linear gradient of solvent B from 10% to 99% across 8 min. Condition 2: separation was achieved using a linear gradient of solvent B from 5% to 99% across 12 min.

Condition 1 for the UPLC separation.

Condition 2 for the UPLC separation.

The predicated molecular mass was calculated using the atom mass of 12C (12.0000), 16O (15.9949) and 1H (1.0078).

The microautoradiography–fluorescence in situ hybridization (MAR‐FISH) technique was applied to identify active oestrone‐assimilating bacteria in activated sludge using [2,4,6,7‐3H(N)]oestrone as a tracer. Some studies have revealed that several active proteobacterial taxa incorporated trace oestrone (submicrogram per litter concentrations) in activated sludges, indicating that the main degraders of oestrogen in wastewater treatment plants are different from those reported in culture‐dependent studies (Zang et al., 2008; Thayanukul et al., 2010; Kurisu et al., 2015). However, this technique has several disadvantages. First, oestrogens are highly hydrophobic; thus, these steroid compounds may easily attach to cell membranes (Lin et al., 2015) or passively transport into cell via the outer membrane transporter (Wiener and Horanyi, 2011; Lin et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2018). Therefore, distinguishing between types of metabolic activities – passive diffusion or active uptake, and redox transformation or complete degradation – of radiolabelled bacterial cells is difficult. Taxonomic identification of labelled cells also relies on oligo probes targeting specific bacterial taxa used in each study, resulting in an incomplete profile of oestrogen‐incorporated bacteria.

Integrated multi‐omics approaches, including (meta)genomic analysis and metabolite profiling, have been applied to identify steroid hormone degraders and their catabolic pathways in environments. Chen et al. (2016) revealed that C. testosteroni spp. play a major role in aerobic androgen degradation in activated sludge based on the detection of the signature metabolite and key gene in the 9,10‐seco pathway, 3‐HSA and tesB. A similar strategy was used to interrogate anaerobic androgen degraders in denitrifying sludge and anoxic estuary sediments. In both ecosystems, the signature metabolite 2,3‐SAOA and degradation key gene atcA were identified, indicating that these microbial communities degrade androgen through the 2,3‐seco pathway. However, the main degraders were Thauera spp. (phylogenetically close to T. terpenica 58Eu) instead of the model organism S. denitrificans DSM 18526 (Yang et al., 2016; Shih et al., 2017). Another example of interrogating environmental hormone degradation is using the 13C‐metabolomic approach to identify major oestrogen degradation pathways in river waters. The occurrence of 13C‐labelled pyridinestrone acid – the dead‐end‐product of the 4,5‐seco pathway – in [3,4C‐13C]oestrone‐treated water samples indicated that river microorganisms degrade natural oestrogens via the 4,5‐seco pathway. These characteristic metabolites or dead‐end‐products were identified using ultra‐performance liquid chromatography–high‐resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC─HRMS). The characteristic metabolites and dead‐end‐products of each pathway and their UPLC─HRMS behaviours are shown in Fig. 6 and Table 5 respectively.

Figure 6.

Characteristic metabolites involved in bacterial steroid degradation pathways. 4‐Norestrogenic acid is the deconjugated structure of a critical CoA‐ester intermediate in the aerobic 4,5‐seco pathway. R at the C17 position represents a keto or hydroxyl or group. *, the corresponding 17‐hydroxyl structures. Abbreviations: ADD, androsta‐1,4‐diene‐3,17‐dione; DSAO, 1,17‐dioxo‐2,3‐secoandrostan‐3‐oic acid; DT, 1‐dehydrotestosterone; HIP, 3aα‐H‐4α(3'‐propanoate)‐7aβ‐methylhexahydro‐1,5‐indanedione; 3‐HSA, 3‐hydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9,17‐dione; 3,17‐DHSA, 3,17‐dihydroxy‐9,10‐seconandrosta‐1,3,5(10)‐triene‐9‐one; PEA, pyridinestrone acid; 2,3‐SAOA, 17‐hydroxy‐1‐oxo‐2,3‐secoandrostan‐3‐oic acid.

Some genome‐based studies have also broadened the diversity of aerobic androgen degraders. Horinouchi et al. (2012) used homology to search for gene clusters related to testosterone degradation in bacterial genomes. The result showed that C. testosteroni KF1, Cupriavidu necator JMP134, Cup. taiwanensis LMG 19424, Ralstonia eutropha H16, Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315l, Burkholderia sp. 383, Shewanella pealeana ATCC700345, S. halifaxensis HAW‐EB4 and Pseudoalteromonas haloplanktis TAC125 are putative androgen degraders due to the high amino acid sequence identity of enzymes involved in the degradation of the testosterone core ring. Recently, a large scale of genomic study using a hidden Markov models (HMMs) search revealed that of the over 8,000 published bacterial genomes, only 256 actinobacterial and proteobacterial genomes harbour the genes involved in the 9,10‐seco pathway. For further validation, nine predicted steroid‐degrading strains were selected for growth experiments and metabolite identification. Among them, only three proteobacterial strains – Pseudomonas resinovorans NBRC106553, Cupriavidus necator ATCC17699 and Sphingomonas wittchii RW1 – and one actinobacterial strain – Amycolatopsis sp. ATCC39166 – are able to degrade testosterone completely (Bergstrand et al., 2016).

Although most steroid hormone degraders were isolated from sludge communities in wastewater treatment plants, it is interesting that some degraders and catabolic activities were identified in soils, coral, or river and marine sediments, as mentioned above. A metagenome analysis further revealed that the genes involved in the aerobic 9,10‐seco pathway (degradation pathway for androgens, bile acids and sterols) are ubiquitous in different natural ecosystems – soils, deep sea, eukaryotic hosts, and even in the Antarctica Dry Valleys – indicating the ecological significance of steroid degraders (Holert et al., 2018). For example, the fact that steroid‐degrading gammaproteobacteria isolated from sponges and corals suggests that microbial steroid metabolism plays a role in symbiosis relationships (mutualism) with their animal hosts (Ding et al., 2016; Holert et al., 2018). Despite this, the actual roles of these degraders in nature ecosystems remain elusive because the hormone degradation activities are mostly identified in chemically defined media or mesocosms supplied with large amount of hormones (micro‐ to milli‐molar), which is much higher (1000‐ to 10 000‐fold) than those detected in environments (Yang et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2016; Shih et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018). It has been speculated that steroid hormone degraders in environments might be members of rare biosphere due to the low content of hormone substrates (Wei et al., 2018). Under a substrate concentration (3.7 nM of oestrone as the sole carbon source) close to environmental levels, pyridinestrone acid – the dead‐end‐product of the 4,5‐seco pathway – was detected in bacterial cultures, indicating that the oestrogen degradation ability of Novosphingobium sp. SLCC remained active (Chen et al., 2018). Moreover, the FISH‐MAR study (Thayanukul et al., 2010) indicated that bacteria are able to assimilate trace oestrogens (submicrogram per litter concentrations). Accordingly, in situ studies of mesocosms periodically amended with a low concentration (nM) of steroid substrate may be essential to elucidate the ecological roles of these rare biospheres in their habitats.

Challenges and future perspectives

Steroid hormone contamination appears to be widespread in various ecosystems, and its long‐term impact on wildlife has been studied in some detail. Elucidating the physiology of microbial degraders and biochemical mechanisms involved in steroid hormone degradation may offer a solution to improve biodegradation efficiency in engineered ecosystems. Although conventional culture‐dependent and molecular approaches have provided insights into each biodegradation step, investigation of steroid hormone biodegradation remains challenging. For example, the fact that most steroid‐degrading anaerobes cannot grow on solid media (e.g. agar plate) makes many molecular biological approaches difficult. Although the oestrogen‐degrading alphaproteobacteria (e.g. Sphingomonas spp. and Novosphingobium spp.) are able to form colonies on agar plates, the presence of glycosphingolipids on their cell wall and the lack of suitable gene transfer vectors increase the difficulties in genetic manipulation (Saito et al., 2006). Fortunately, the combination of transcriptomic analysis and metabolite profiling provides an alternative to determining the steps in the 2,3‐seco and 4,5‐seco pathways. Nevertheless, the information regarding the steroid B‐ring degradation in anaerobic proteobacterial degraders, steroid hormone chemosensory and steroid transport systems remains unclear. Thus, the isolation of suitable bacterial strains for molecular biological approaches is crucial for future studies on steroid biodegradation.

The ecological role of steroid hormone degraders in environments remains uncertain. Metagenomics is a conventional approach to address ecological relevance of microbial hormone degradation, but challenges remain because sequences of degradation genes usually comprise low coverage within metagenome data set (Holert et al., 2018). This might be due to the low abundance of microbial degraders in ecosystems where the hormone input is low (Wei et al., 2018). As a result, interrogation on ecosystems with long‐term hormone contamination may expand new insights into diversity of hormone degraders and catabolic genes. Moreover, recent discoveries of steroid degraders in eukaryotic hosts (Ding et al., 2016; Holert et al., 2018) suggest a bidirectional interaction between steroid degraders and their eukaryotic hosts. The discovery of cobalamin auxotrophy in many steroid‐degrading anaerobes (Wei et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019) indicates cobalamin cross‐feedings within microbial communities. These findings may also offer another avenue for future studies.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the generous financial support by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 107‐2311‐B‐001 ‐021 ‐MY3).

Microbial Biotechnology (2020) 13(4), 926–949

Funding Information

No funding information provided.

References

- Adams, M.A. , Teeter, J.H. , Katz, Y. , and Johnson, P.B. (1987) Sex‐pheromones of the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) ‐ steroid studies. J Chem Ecol 13: 387–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albero, B. , Sánchez‐Brunete, C. , Miguel, E. , Pérez, R.A. , and Tadeo, J.L. (2013) Analysis of natural‐occurring and synthetic sexual hormones in sludge‐amended soils by matrix solid‐phase dispersion and isotope dilution gas chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A 1283: 39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, H. , Siegrist, H. , Halling‐Sorensen, B. , and Ternes, T.A. (2003) Fate of estrogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant. Environ Sci Technol 37: 4021–4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris, A.Z. , Shamsuddin, A.S. , and Praveena, S.M. (2014) Occurrence of 17α‐ethynylestradiol (EE2) in the environment and effect on exposed biota: a review. Environ Int 69: 104–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baronti, C. , Curini, R. , D’Ascenzo, G. , Di Corcia, A. , Gentili, A. , and Samperi, R. (2000) Monitoring natural and synthetic estrogens at activated sludge sewage treatment plants and in a receiving river water. Environ Sci Technol 34: 5059–5066. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, B.W. , and El Eini, D.I. (1976) Solubilization of hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, testosterone and progesterone by long‐chain polyoxyethylene surfactants. J Pharm Pharmacol 28: 210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baza´es, A. , and Schmachtenberg, O. (2012) Odorant tuning of olfactory crypt cells from juvenile and adult rainbow trout. J Exp Biol 215: 1740–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfroid, A.C. , Van der Horst, A. , Vethaak, A.D. , Schäfer, A.J. , Rijs, G.B. , Wegener, J. , and Cofino, W.P. (1999) Analysis and occurrence of estrogenic hormones and their glucuronides in surface water and waste water in the Netherlands. Sci Total Environ 225: 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrand, L.H. , Cardenas, E. , Holert, J. , Van Hamme, J.D. , and Mohn, W.W. (2016) Delineation of steroid‐degrading microorganisms through comparative genomic analysis. MBio 7: e00166‐16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerregaard, L. , Madsen, A. , Korsgaard, B. , and Bjerregaard, P. (2006) Gonad histology and vitellogenin concentrations in brown trout (Salmo trutta) from Danish streams impacted by sewage effluent. Ecotoxicology 15: 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortone, S.A. , Davis, W.P. , and Bundrick, C. M. (1989) Morphological and behavioral characters in mosquitofish as potential bioindication of exposure to kraft mill effluent. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 43: 370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capyk, J.K. , Casabon, I. , Gruninger, R. , Strynadka, N.C. , and Eltis, L.D. (2011) Activity of 3‐ketosteroid 9α‐hydroxylase (KshAB) indicates cholesterol side chain and ring degradation occur simultaneously in Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Biol Chem 286: 40717–40724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, P.G. , Rodrigues, D. , Madureira, T.V. , Oliveira, N. , Rocha, M.J. , and Rocha, E. (2017) Warming modulates the effects of the endocrine disruptor progestin levonorgestrel on the zebrafish fitness, ovary maturation kinetics and reproduction success. Environ Pollut 229: 300–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casabon, I. , Crowe, A.M. , Liu, J. , and Eltis, L.D. (2013) FadD3 is an acyl‐CoA synthetase that initiates catabolism of cholesterol rings C and D in actinobacteria. Mol Microbiol 87: 269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali, N. , and Riley, L.W. (2007) A phylogenetic analysis of the actinomycetales mce operons. BMC Genom 8: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. , Wan, Y. , and Hu, J. (2009) Determination and source apportionment of five classes of steroid hormones in urban rivers. Environ Sci Technol 43: 7691–7698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, H. , Wan, Y. , Wu, S. , Fan, Z. , and Hu, J. (2011) Occurrence of androgens and progestogens in wastewater treatment plants and receiving river waters: comparison to estrogens. Water Res 45: 732–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.Y. , Wen, T.Y. , Wang, G.S. , Cheng, H.W. , Lin, Y.H. , and Lien, G.W. (2007) Determining estrogenic steroids in Taipei waters and removal in drinking water treatment using high‐flow solid phase extraction and liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Sci Total Environ 378: 352–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.S. , Chen, T.C. , Yeh, K.J.C. , Chao, H.R. , Liaw, E.T. , Hsieh, C.Y. , et al. (2010) High estrogen concentrations in receiving river discharge from a concentrated livestock feedlot. Sci Total Environ 408: 3223–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L. , Wang, C.H. , Yang, F.C. , Ismail, W. , Wang, P.H. , Wu, Y.C. , and Chiang, Y.R. (2016) Identification of Comamonas testosteroni as an androgen degrader in sewage. Sci Rep 6: 35386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L. , Yu, C.P. , Lee, T.H. , Goh, K.S. , Chu, K.H. , Wang, P.H. , et al. (2017) Biochemical mechanisms and catabolic enzymes involved in bacterial estrogen degradation pathways. Cell Chem Biol 24: 712.e7–724.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L. , Fu, H.Y. , Lee, T.H. , Shih, C.J. , Huang, L. , Wang, Y.S. , et al. (2018) Estrogen degraders and estrogen degradation pathway identified in an activated sludge. Appl Environ Microbiol 84: e00001‐18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.L. , Wei, S. , and Chiang, Y.R. (2019) Genome analysis of the steroid‐degrading denitrifying Denitratisoma oestradiolicum DSM 16959 and Denitratisoma sp. strain DHT3. bioRxiv 10.1101/710707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.R. , Ismail, W. , Gallien, S. , Heintz, D. , Van Dorsselaer, A. , and Fuchs, G. (2008a) Cholest‐4‐en‐3‐one‐Δ1‐dehydrogenase: a flavoprotein catalyzing the second step in anoxic cholesterol metabolism. Appl Environ Microbiol 74: 107–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.R. , Ismail, W. , Heintz, D. , Schaeffer, C. , Van Dorsselaer, A. , and Fuchs, G. (2008b) Study of anoxic and oxic cholesterol metabolism by Sterolibacterium denitrificans . J Bacteriol 190: 905–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, Y.R. , Fang, J.Y. , Ismail, W. , and Wang, P.H. (2010) Initial steps in anoxic testosterone degradation by Steroidobacter denitrificans . Microbiology 156: 2253–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombe, R.G. , Tsong, Y.Y. , Hamilton, P.B. , and Sih, C.J. (1966) Mechanisms of steroid oxidation by microorganisms. X. Oxidative cleavage of estrone. J Biol Chem 241: 1587–1595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, A.M. , Stogios, P.J. , Casabon, I. , Evdokimova, E. , Savchenko, A. , and Eltis, L.D. (2015) Structural and functional characterization of a ketosteroid transcriptional regulator of Mycobacterium tuberculosis . J Biol Chem 290: 872–882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, A.M. , Casabon, I. , Brown, K.L. , Liu, J. , Lian, J. , Rogalski, J.C. , et al. (2017) Catabolism of the last two steroid rings in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other bacteria. MBio 8: e00321‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, A.M. , Workman, S.D. , Watanabe, N. , Worrall, L.J. , Strynadka, N.C.J. , and Eltis, L.D. (2018) IpdAB, a virulence factor in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is a cholesterol ring‐cleaving hydrolase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: E3378–E3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czajka, C.P. , and Londry, K.L. (2006) Anaerobic biotransformation of estrogens. Sci Total Environ 367: 932–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagley, S. , Evans, W.C. , and Ribbons, D.W. (1960) New pathways in the oxidative metabolism of aromatic compounds by micro‐organisms. Nature 188: 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, J.Y. , Shiu, J.H. , Chen, W.M. , Chiang, Y.R. , and Tang, S.L. (2016) Genomic insight into the host‐endosymbiont relationship of Endozoicomonas montiporae CL‐33(T) with its coral host. Front Microbiol 7: 251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokras, A. (2016) Noncontraceptive use of oral combined hormonal contraceptives in polycystic ovary syndrome‐risks versus benefits. Fertil Steril 106: 1572–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donova, M.V. (2007) Transformation of steroids by actinobacteria: a review. Appl Biochem Microbiol 43: 1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donova, M.V. , and Egorova, O.V. (2012) Microbial steroid transformations: current state and prospects. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 94: 1423–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, W.I. , and Meeks, J.P. (2018) Excreted steroids in vertebrate social communication. J Neurosci 38: 3377–3387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekiert, D.C. , Bhabha, G. , Isom, G.L. , Greenan, G. , Ovchinnikov, S. , Henderson, I.R. , et al. (2017) Architectures of lipid transport systems for the bacterial outer membrane. Cell 169: 273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrbach, M. , Kuever, J. , Meinke, R. , Kämpfer, P. , and Hollender, J. (2006) Denitratisoma oestradiolicum gen. nov., sp. nov., a 17β‐oestradiol‐degrading, denitrifying betaproteobacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56: 1547–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrbach, M. , Kuever, J. , Remesch, M. , Huber, B.E. , Kämpfer, P. , Dott, W. , and Hollender, J. (2008) Steroidobacter denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a steroidal hormone‐degrading gammaproteobacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58: 2215–2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z. , Casey, F.X. , Hakk, H. , and Larsen, G.L. (2007) Persistence and fate of 17beta‐estradiol and testosterone in agricultural soils. Chemosphere 67: 886–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Z. , Wu, S. , Chang, H. , and Hu, J. (2011) Behaviors of glucocorticoids, androgens and progestogens in a municipal sewage treatment plant: comparison to estrogens. Environ Sci Technol 45: 2725–2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, P. , Cruz, A. , Angelova, B. , Pinheiro, H.M. , and Cabral, J.M.S. (2003) Microbial conversion of steroid compounds: recent developments. Enzyme Microb Tec 32: 688–705. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de las Heras, L. , García Fernández, E. , María Navarro Llorens, J. , Perera, J. , and Drzyzga, O. (2009) Morphological, physiological, and molecular characterization of a newly isolated steroid‐degrading actinomycete, identified as Rhodococcus ruber strain Chol‐4. Curr Microbiol 59: 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández de las Heras, L. , van der Geize, R. , Drzyzga, O. , Perera, J. , and María Navarro Llorens, J. (2012) Molecular characterization of three 3‐ketosteroid‐Δ(1)‐dehydrogenase isoenzymes of Rhodococcus ruber strain Chol‐4. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 132: 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez de las Heras, L. , Alonso, S. , de la Vega de Leon, A. , Xavier, D. , Perera, J. , and Navarro Llorens, J.M. (2013) Draft genome sequence of the steroid degrader Rhodococcus ruber strain Chol‐4. Genome Announc 1: e00215‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foss, S. , and Harder, J. (1998) Thauera linaloolentis sp. nov. and Thauera terpenica sp. nov., isolated on oxygen‐containing monoterpenes (linalool, menthol, and eucalyptol) nitrate. Syst Appl Microbiol 21: 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, K. , Satomi, M. , Morita, N. , Motomura, T. , Tanaka, T. , and Kikuchi, S. (2003) Novosphingobium tardaugens sp. nov., an oestradiol‐degrading bacterium isolated from activated sludge of a sewage treatment plant in Tokyo. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 53: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghayee, H.K. , and Auchus, R.J. (2007) Basic concepts and recent developments in human steroid hormone biosynthesis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 8: 289–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorga, M. , Insa, S. , Petrovic, M. , and Barcelo, D. (2015) Occurrence and spatial distribution of EDCs and related compounds in waters and sediments of Iberian rivers. Sci Total Environ 503–504: 69–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara, G. , Heras, L.F.L. , Perera, J. , and Llorens, J.M. N. (2017) Functional characterization of 3‐ketosteroid 9α‐hydroxylases in Rhodococcus ruber strain chol‐4. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 172: 176–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland, M.E. , and Reynolds, J.A. (1973) Self‐association of cholesterol in aqueous solution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 70: 2313–2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, H. , and Eskicioglu, C. (2012) Fate of estrogenic hormones in wastewater and sludge treatment: a review of properties and analytical detection techniques in sludge matrix. Water Res 46: 5813–5833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannich, J.T. , Umebayashi, K. , and Riezman, H. (2011) Distribution and functions of sterols and sphingolipids. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a004762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanselman, T.A. , Graetz, D.A. , and Wilkie, A.C. (2003) Manure‐borne estrogens as potential environmental contaminants: a review. Environ Sci Technol 37: 5471–5478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder, J. , and Probian, C. (1997) Anaerobic mineralization of cholesterol by a novel type of denitrifying bacterium. Arch Microbiol 167: 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, S. , Bessho, H. , Hara, A. , Nakamura, M. , Iguchi, T. , and Fujita, K. (2000) Elevated serum vitellogenin levels and gonadal abnormalities in wild male flounder (Pleuronectes yokohamae) from Tokyo Bay. Japan Mar Environ Res 49: 37–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haubrick, L.L. , and Assmann, S.M. (2006) Brassinosteroids and plant function: some clues, more puzzles. Plant Cell Environ 29: 446–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holert, J. , Yücel, O. , Suvekbala, V. , Kulić, Ž. , Möller, H. , and Philipp, B. (2014) Evidence of distinct pathways for bacterial degradation of the steroid compound cholate suggests the potential for metabolic interactions by interspecies cross‐feeding. Environ Microbiol 16: 1424–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holert, J. , Cardenas, E. , Bergstrand, L.H. , Zaikova, E. , Hahn, A.S. , Hallam, S.J. , and Mohn, W.W. (2018) Metagenomes reveal global distribution of bacterial steroid catabolism in natural, engineered, and host Environments. MBio 9: e02345‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homklin, S. , Ong, S. K. , and Limpiyakorn, T. (2011) Biotransformation of 17alpha‐methyltestosterone in sediment under different electron acceptor conditions. Chemosphere 82: 1401–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi, M. , Yamamoto, T. , Taguchi, K. , Arai, H. , and Kudo, T. (2001) Meta‐cleavage enzyme gene tesB is necessary for testosterone degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441. Microbiology 147: 3367–3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi, M. , Hayashi, T. , Koshino, H. , Yamamoto, T. , and Kudo, T. (2003) Gene encoding the hydrolase for the product of the metacleavage reaction in testosterone degradation by Comamonas testosteroni . Appl Environ Microbiol 69: 2139–2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi, M. , Kurita, T. , Yamamoto, T. , Hatori, E. , Hayashi, T. , and Kudo, T. (2004) Steroid degradation gene cluster of Comamonas testosteroni consisting of 18 putative genes from meta‐cleavage enzyme gene tesB to regulator gene tesR . Biochem Biophys Res Commun 324: 597–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi, M. , Hayashi, T. , and Kudo, T. (2012) Steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni . J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 129: 4–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horinouchi, M. , Koshino, H. , Malon, M. , Hirota, H. , and Hayashi, T. (2018) Steroid degradation in Comamonas testosteroni TA441: identification of metabolites and the genes involved in the reactions necessary before D‐ring cleavage. Appl Environ Microbiol 84: e01324–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck, L.D. (2009) Pheromone communication in amphibians and reptiles. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, W.M. , Black, D.A. , and Bortone, S.A. (1980) Abnormal expression of secondary sex characters in a population of mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis holbrooki: evidence for environmentally‐induced masculinization. Copeia 4: 676–681. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C.H. , and Sedlak, D.L. (2001) Analysis of estrogenic hormones in municipal wastewater effluent and surface water using enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay and gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Environ Toxicol Chem 20: 133–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, B. , Wang, B. , Ren, D. , Jin, W. , Liu, J. , Peng, J. , and Pan, X. (2013) Occurrence, removal and bioaccumulation of steroid estrogens in Dianchi Lake catchment, China. Environ Int 59: 262–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins, S.R. , White, M.V. , Hudson, F.M. , and Fine, D.D. (2007) Analysis of lagoon samples from different concentrated animal feeding operations for estrogens and estrogen conjugates. Environ Sci Technol 41: 738–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R. , Wilson, E. , Angus, R. , Howell, W. , and Kirk, M. (2003) Androstenedione and progesterone in the sediment of a river receiving paper mill effluent. Toxicol Sci 73: 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobling, S. , Williams, R. , Johnson, A. , Taylor, A. , Gross‐Sorokin, M. , Nolan, M. , et al. (2006) Predicted exposures to steroid estrogens in U.K. rivers correlate with widespread sexual disruption in wild fish populations. Environ Health Perspect 114: 32–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]