Highlights

-

•

A healthcare facility-based investigation of an outbreak would have been limited.

-

•

Clinic-based case identification in this chikungunya outbreak would only have identified a quarter of all cases.

-

•

Community-based household investigation involving only case households revealed that cases were more likely to be female and had lower educational attainment.

-

•

Community-based investigation involving all households additionally identified clothing that exposed both limbs and traveling outside the district as risk factors.

-

•

Outbreak investigations that identify cases in community and enroll controls from across the community should be used for better understanding of the risk factors as well as community transmission estimates.

Keywords: Chikungunya, Community Controls, Community-Based Investigation, Hospital-Based Investigation, Incidence of Chikungunya, Outbreak Investigation, Risk Factors of Chikungunya

Abstract

Background

Outbreak investigations typically focus their efforts on identifying cases that present at healthcare facilities. However, these cases rarely represent all cases in the wider community. In this context, community-based investigations may provide additional insight into key risk factors for infection, however, the benefits of these more laborious data collection strategies remains unclear.

Methods

We used different subsets of the data from a comprehensive outbreak investigation to compare the inferences we make in alternative investigation strategies.

Results

The outbreak investigation team interviewed 1,933 individuals from 460 homes. 364 (18%) of individuals had symptoms consistent with chikungunya. A theoretical clinic-based study would have identified 26% of the cases. Adding in community-based cases provided an overall estimate of the attack rate in the community. Comparison with controls from the same household revealed that those with at least secondary education had a reduced risk. Finally, enrolling residents from households across the community allowed us to characterize spatial heterogeneity of risk and identify the type of clothing usually worn and travel history as risk factors. This also revealed that household-level use of mosquito control was not associated with infection.

Conclusions

These findings highlight that while clinic-based studies may be easier to conduct, they only provide limited insight into the burden and risk factors for disease. Enrolling people who escaped from infection, both in the household and in the community allows a step change in our understanding of the spread of a pathogen and maximizes opportunities for control.

Introduction

Infectious disease outbreaks have the potential to place a significant burden on public health resources. Understanding who is at risk of becoming infected is critical for the focused targeting of interventions. Due to relative ease of access and limited cost requirements, outbreak investigations typically focus on cases that present at formal healthcare centers such as hospitals or community clinics. For example, data collection performed as part of epidemiological investigations during the recent epidemics of Ebola, Zika and MERS focused on quantifying the number of cases and their characteristics (Al-Abdallat et al., 2014; Lu et al., 2015; Teixeira et al., 2016). These case-counting exercises provided key insights into fundamental epidemiological parameters such as the basic reproductive number and case fatality rates, and allowed the projection of the future course of the epidemic (Aylward et al., 2014; Lessler et al., 2014; Lewnard et al., 2014; Yamin et al., 2015). However, without information on the underlying population, and especially characteristics of individuals who avoid infection, these approaches limit our ability to make mechanistic insights, quantify burden of disease, and identify risk factors for infection, hampering efforts to develop targeted control strategies.

Cases that present at healthcare centers may only represent a small minority of all cases. In addition, some individuals are more likely to visit formal healthcare providers than others, including those with more severe illness, and differences in healthcare seeking can vary by age, gender and socioeconomic status (Chowdhury et al., 2007; Nikolay et al., 2017; Pandey et al., 2002). Household-based outbreak investigations, where investigation teams visit affected communities, permit a more comprehensive understanding of pathogen spread that limits the impact of healthcare seeking patterns (France et al., 2010). However, these investigations are usually still focused on identifying individuals that got sick (Boore et al., 2013; France et al., 2010) Without also understanding who is avoiding infection in a community, it is difficult to identify the key risk factors for infection, limiting potential inferences. The possible insights from alternative investigation strategies have not previously been systematically compared. Here, we use the results of a detailed chikungunya outbreak investigation from Bangladesh as an example to consider the inferences made under different investigation scenarios.

Chikungunya virus is a mosquito-borne alphavirus transmitted to humans by Aedes mosquitoes causing acute fever, joint pain, and skin rash.(Aubry et al., 2015) Chikungunya fever was first recognized in 1952 in Tanzania.(Lumsden, 1955) Since then, outbreaks of chikungunya have been regularly identified across the tropics and sub-tropics. The first chikungunya outbreak in Bangladesh was identified in 2008 in two northwestern districts bordering India (icddr,b, 2008). Since then regular outbreaks have been detected.(Khatun et al., 2015; Salje et al., 2016) Here we use the results from a detailed investigation of an outbreak of chikungunya virus in a village in Tangail, Bangladesh where the outbreak team visited every household in the community and interviewed all members in each household. The comprehensive household investigation captured both those who did get infected and those that escaped from infection. The objective of this study was to compare our approach, in terms of the inferences about the outbreak, to more limited investigation strategies.

Methods

Case finding

In late November 2012, a local health official of Gopalpur sub-district in Tangail district reported an outbreak of fever and severe joint pain to Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) of the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Bangladesh. At the end of November 2012, a collaborative team of the IEDCR and International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b) began an investigation in the reported village to determine the etiology of the outbreak, describe the demographics and clinical presentation of cases, and to identify the potential risk factors associated with the outbreak. The investigation team visited the village and approached every member of all households in the village; all households in the village consented to being enrolled in the study. Questionnaires were administered in all households to identify suspected cases, identify demographic characteristics, and travel histories of individuals within households. Suspect cases were defined as residents with acute onset of fever with rash or joint pain within 6 months prior to beginning the investigation.

Data collection

Study staff administered questionnaires to household heads about household members' demographic data and history of illness, water source, construction materials, and mosquito control measures in the household. Potential mosquito breeding containers in and around the participating households with stored water were inspected for presence of larvae. Suspected cases were asked about their symptoms with onset date and specifics about their treatment seeking behavior. The GPS location of all homes was also recorded.

Determining the etiology of the outbreak

All household members, irrespective of their suspected case status, were asked to provide a single 5 ml blood specimen for laboratory testing. Blood specimens were spun in the field to separate serum, which were then stored on ice and transported to the virology laboratory of IEDCR. The serum samples were tested for IgM antibodies against chikungunya by enzyme linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) (Standard Diagnostics, Inc., South Korea). Suspected case-patients who had IgM antibodies against chikungunya in their serum were termed laboratory confirmed cases.

Datasets

We created four different datasets that allowed us to consider different outbreak investigation strategies:

(A) Clinic-based case identification

This dataset consisted of all suspect cases that reported that they visited a formal healthcare setting (defined as government or non-government primary healthcare center/clinic/hospital) following the onset of symptoms.

(B) Community-based case identification

This dataset consisted of all suspect cases, irrespective of their healthcare seeking behaviors.

(C) Community-based household investigation (case households only)

This dataset consisted of all suspect cases plus controls consisting of household members of these cases.

(D) Community-based household investigation (all households)

This dataset consisted of all members of all households in the community, regardless of symptoms.

Data analysis

The epidemic curve was constructed using symptom onset date of chikungunya cases. GPS locations of households with and without chikungunya cases were used to prepare spatial distribution maps. For the case-only datasets (datasets A and B), we compared the age and sex distribution of the cases with that for the district from the 2011 census (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, 2011). For the datasets with information on individuals who escaped from infection (datasets C and D), we initially used simple logistic regression to compare the demographics, typical apparel worn, travel history within the last six months, and household characteristics of cases with non-cases. We then built multivariable logistic regression models to identify adjusted risk factors for chikungunya fever. We initially placed all variables with a p-value of <0.05 in the unadjusted analysis into a multivariable model. We then used backward stepwise selection using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Sauerbrei et al., 2007) to identify the best model.

Sensitivity analyses

Not all individuals who get infected will present with symptoms. We attempted to capture these individuals by asking for blood samples from all community members. To assess the impact of misclassifying asymptomatically infected individuals as controls in datasets C and D, we conducted sensitivity analyses where these individuals were reclassified as cases.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided written informed consent prior to interviews and blood specimen collection and the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of Bangladesh reviewed and approved the outbreak investigation plan.

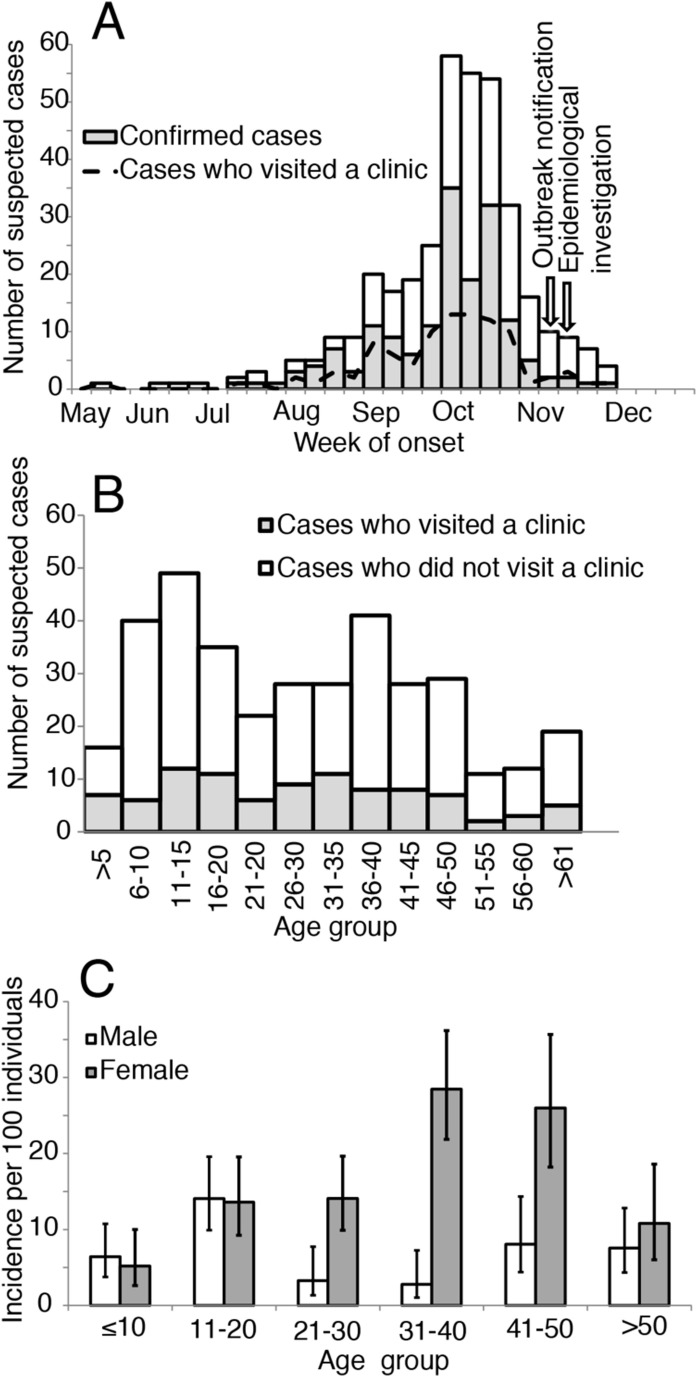

Results

The outbreak investigation team visited every household and interviewed all 1,933 individuals from all 460 households of the village. A total of 364 (18%) individuals reported having suffered from fever with rash or joint pain between May 29 and December 1, 2012, of them 242 (66%) individuals consented to provide serum samples. In addition, 171 (11%) of 1,569 individuals without any symptoms agreed to provide serum samples. IgM antibodies against chikungunya virus were detected in 166 (69%) of 242 symptomatic individuals and 48 (28%) of 171 individuals without symptoms consistent with chikungunya infection. From the beginning of August, the number of chikungunya fever cases started to rise quickly, peaking during October 2012 (Fig. 1 : Panel A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Suspected chikungunya cases who presented to the clinic, confirmed cases, and all suspected cases by week of illness onset, Tangail, Bangladesh, May 29-December 01, 2012 (B) Age group distribution of suspected chikungunya cases, by healthcare seeking status (C) Incidence of chikungunya infection per 100 population according to age group and sex

Inferences from clinic-based case detection

Ninety-five suspect cases reported visiting a formal healthcare facility for symptoms consistent with chikungunya between July and November, with the peak number of cases occurring in October (Fig. 1: Panel A). Cases sought care in three different centers: 25 sought care in a government run community clinic, 8 in a government run sub-district health complex and 62 in a private clinic. The median age was 28 years (interquartile range (IQR) = 14-45 years) and the majority (60%) were female (Table 1 ). If we used the age and sex distribution of the district from the 2011 national census, we find that there is an increased risk of disease in those between the ages of 30-49 compared to those aged below 10 years (OR 2.51, 95% 1.24-5.51) and that females were at increased risk of infection compared to males (OR of 1.43, 95% CI: 0.94-2.23) (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Comparison of age, sex, and clinical characteristics of suspected cases who sought care in a clinic with all suspected chikungunya cases in Tangail, Bangladesh, 2012.

| Characteristics | Cases who sought care in a clinic (N = 95) | All cases (N = 364) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (IQR) | 28 (14-45) | 30 (14-43) | 0.372 |

| Age group (in years) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| 0-9 | 11 (12) | 47 (13) | 0.870 |

| 10-19 | 23 (24) | 85 (23) | |

| 20-29 | 15 (16) | 48 (13) | |

| 30-49 | 33 (35) | 123 (34) | |

| 50-59 | 5 (5) | 29 (8) | |

| 60-64 | 4 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| 65 and above | 4 (4) | 19 (5) | |

| Female | 57 (60) | 208 (57) | |

| Educational status | |||

| No formal education | 19 (20) | 90 (24) | 0.086 |

| Up to primary school | 27 (28) | 112 (31) | |

| Up to secondary school | 35 (37) | 130 (36) | |

| Higher secondary and above | 14 (15) | 32 (9) | |

| Signs and symptoms | |||

| Fever | 95 (100) | 364 (100) | |

| Joint pain | 77 (81) | 293 (80) | |

| Rash | 65 (68) | 227 (62) | |

| Itching | 20 (21) | 75 (21) | |

| Myalgia | 8 (8) | 30 (8) | |

| Headache | 6 (6) | 26 (7) | |

| Provided blood sample | 65 (68) | 236 (65) | 0.221 |

| IgM against chikungunya | 51 (78) | 166 (70) | |

| Bed ridden for at least 3 days | 89 (94) | 318 (87) | |

| Reported daily use of anti-mosquito coil | 60 (63) | 222 (61) | 0.614 |

| Typical apparel exposes | |||

| Upper limbs only | 65 (69) | 235 (64) | 0.502 |

| Lower limbs only | 5 (5) | 28 (8) | |

| Both upper and lower limbs | 25 (26) | 101 (28) | |

| Travelled outside Tangail district in last six months | 39 (41) | 102 (28) | 0.001 |

| Mosquito larvae observed in the household premise | 19 (20) | 75 (21) | 0.865 |

IgM = Immunoglobulin M.

IQR = Interquartile range.

Table 2.

Factors associated with chikungunya fever using different strategies, Tangail, Bangladesh, 2012.

| Characteristics | A. Clinic-based cases | B. All cases | C. Household controls | D. Community controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: | ||||

| 0-9 | 0.40 (0.18-0.81) | 0.46 (0.32-0.64) | 0.60 (0.38-0.95) | 0.52 (0.34-0.78) |

| 10-19 | 0.97 (0.54-1.70) | 0.96 (0.72-1.28) | 0.76 (0.49-1.18) | 0.84 (0.60-1.17) |

| 20-29 | 0.67 (0.34-1.27) | 0.57 (0.40-0.81) | 0.57 (0.37-0.89) | 0.58 (0.41-0.83) |

| 30-49 | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| 50-59 | 0.55 (0.17-1.40) | 0.85 (0.55-1.28) | 0.63 (0.36-1.10) | 0.82 (0.52-1.30) |

| 60-64 | 1.01 (0.26-2.85) | 0.88 (0.46-1.57) | 0.59 (0.26-1.36) | 0.82 (0.43-1.58) |

| 65 and above | 0.52 (0.13-1.47) | 0.67 (0.39-1.09) | 0.45 (0.23-0.88) | 0.65 (0.37-1.15) |

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Female | 1.43 (0.94-2.23) | 1.28 (1.03-1.58) | 1.75 (1.31-2.36) | 1.62 (1.29-2.03) |

| Typical apparel exposure: | ||||

| Upper limbs only | Not possible | Not possible | Ref | Ref |

| Lower limbs only | Not possible | Not possible | 1.11 (0.65-1.93) | 1.34 (0.79-2.28) |

| Both upper and lower limbs | Not possible | Not possible | 1.02 (0.74-1.40) | 1.80 (1.30-2.50) |

| Travelled in <6 months | Not possible | Not possible | 1.27 (0.91-1.76) | 1.47 (1.06-2.03) |

| Education: | ||||

| No formal education | Not possible | Not possible | Ref | Ref |

| Up to primary school | Not possible | Not possible | 0.77 (0.49-1.21) | 1.24 (0.86-1.80) |

| Up to secondary school | Not possible | Not possible | 0.64 (0.42-0.98) | 1.06 (0.74-1.53) |

| Higher secondary and above | Not possible | Not possible | 0.28 (0.17-0.47) | 0.38 (0.24-0.62) |

| Number of household members | ||||

| 1-4 | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | Ref |

| 5 and above | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | 1.00 (0.79-1.26) |

| Number of rooms in the household | ||||

| 1-3 | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | Ref |

| 4 and above | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | 1.11 (0.82-1.51) |

| Mosquito larvae observed in the household premise | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | 0.87 (0.66-1.16) |

| Reported daily use of anti-mosquito coil | Not possible | Not possible | Not possible | 1.03 (0.82-1.31) |

Inferences from community-based case detection

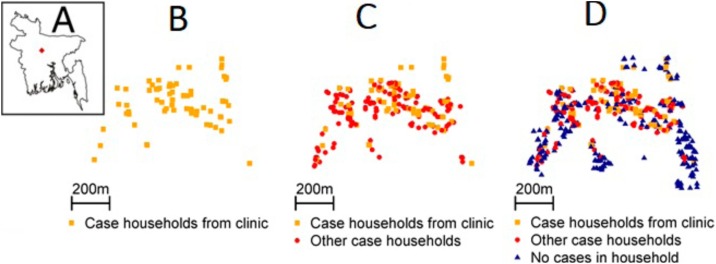

An additional 269 suspect cases were identified in the community who did not seek care in formal healthcare facilities. Of these, 246 individuals visited a local pharmacy and 21 individuals visited the informal sector (unlicensed medical practitioner, traditional healer, and homeopath). The distribution of dates of symptom onset for all cases was nearly identical to the distribution for those that visited clinics (Spearman correlation of 0.95) (Fig. 1A). The proportion of suspect cases visiting a clinic varied between 18% in 51-55 years age group and 44% in ≤5 years age group (Fig. 1B). The conclusions about age, sex, educational levels, use of mosquito controls and clinical presentation of suspect cases were similar when using datasets of all cases or only those that sought care in clinics (Table 1), however, those who presented to clinics were more likely to travel outside the district (41% vs 28%, p-value 0.001). Cases who attended formal healthcare settings also appeared to come from similar parts of the community as cases who did not (Fig. 2 A-B). Similar to the analysis using clinical cases only, using data from the national census identified increasing risk among females for being a case (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Location of cases in the outbreak affected community. (A) Location of outbreak affected village within Bangladesh (B) Case households who appeared in a clinic. (C) All case households. (D) All case and control households.

Inference from community cases plus controls from same household

Incorporating controls from the households where cases reside allowed us to assess additional potential risk factors for being a case. Consistent with inferences using census data, logistic regression models that used household controls also identified increased risk among females (aOR 1.75, 95% CI 1.31-2.36) (Table 2). In addition, this analysis showed that cases were significantly less likely to have secondary (aOR 0.64, 95% CI 0.42-0.98) or more formal (higher secondary) education (aOR 0.28, 95% CI 0.17-0.47) compared to the household controls.

Inference from community cases plus controls from all community households

Incorporating data from the entire community showed that the chikungunya outbreak was largely constrained to the center of the village, with few households affected on the east and west borders but virtually all households affected in the center (Fig. 2C). This is despite the entire community only being a few hundred meters wide. The expanded dataset also allowed us to understand the risk factors for infection in the wider community. As with the previous analyses, females had an increased risk of being a case (OR: 1.62, 95% CI 1.29-2.03) (Table 2), although the difference by sex was concentrated in adults with no difference among children (Fig. 1C). Further individuals who reported usually wearing clothing that exposed both limbs had 1.80 the odds of being a case compared to individuals wearing clothing that exposed upper limbs only (95% CI 1.30-2.50). Those who had travelled outside Tangail district within the last six months also had increased odds of being a case (aOR 1.47, 95% CI 1.06-2.03). Individuals who had higher secondary or more formal education (aOR 0.38, 95% CI 0.24-0.62) were less likely to be a case than individuals without formal education. We did not identify any household characteristics that were associated with being a case, including presence of mosquito larvae (aOR 0.87, 95% CI: 0.66-1.16), daily use of anti-mosquito coil (aOR 1.03, 95% CI: 0.82-1.31), number of household members (aOR 1.00, 95% CI: 0.79-1.26), and number of rooms in the household (aOR 1.11, 95% CI: 0.82-1.51).

Implication of asymptomatic transmission

Fifty-two individuals without symptoms tested positive for CHIKV. We found no significant demographic differences between symptomatic suspected cases and IgM-confirmed asymptomatic cases in those who gave blood (Table S1). In sensitivity analysis, we removed these individuals from the ‘control’ population and included them in the ‘case’ populations. Risk factors for being a case identified in the previous analysis remained similar in both scenarios where we considered household contacts as controls and individuals from all community households as controls (supplementary information, Table S4). However, we found important differences in the probability of providing blood. Those with symptoms were 6.1 times more likely to provide blood than those without symptoms. Further, among asymptomatic individuals, only 2% of children 0-9 years provided a sample compared to 15% among those 30-49 (Table S2). There were also significant differences by sex (14% of asymptomatic males gave blood compared to 8% of females, p-value <0.001) and educational level with more educated people less likely to provide samples (Table S2).

Discussion

Outbreak investigations are central to informed responses to public health emergencies caused by the emergence of an infectious pathogen. However, outbreak investigations currently largely revolve around case-counting exercises that limit our ability to identify who is at risk for infection and who is not. Here, by using the results of a comprehensive outbreak investigation, we have been able to explicitly explore the impact of different investigation strategies in the same outbreak. We found that a clinic-based study that used data from all the formal healthcare settings would have identified a quarter of all cases and, using census data, have correctly identified female sex as an important risk factor for disease. However, it is only through the recruitment of people who did not get sick that we could identify the importance of travel history, educational level and apparel usage in determining who gets sick. Controls from the wider community were also required to demonstrate which household-level characteristics were important for risk, showing that the use of mosquito coils was not protective, and to map spatial heterogeneity in risk, key to intervention development and deployment.

This study highlights the significant heterogeneity in healthcare seeking. Even in a small community such as this, cases visited nine different sources of healthcare, three of which could be considered formal healthcare settings. Infectious disease surveillance activities are unlikely to be able to collate datasets from this diverse range of healthcare sources, even among only those within formal sector, suggesting that outbreak investigations that rely on cases that seek healthcare likely substantially underestimate the magnitude of outbreaks.

Using the results of our study, we provide our assessment of the ability of different investigation strategies to capture key characteristics of an outbreak (Table 3 ). In practice, the decision to expand outbreak investigations beyond information available from healthcare systems will depend on the resources available. Where outbreak teams are already performing community-based case-investigations, the additional time and effort to also collect data on those without symptoms – both from case-households as well as neighboring households – may be marginal. This comprehensive outbreak investigation employed ten field-based investigators and took seven days to complete. An investigation strategy only focused on cases in the community would have taken only marginally less person-time as finding cases in the community anyway typically requires comprehensive door-to-door surveys. Our findings highlight how this additional data collection effort can help reveal the drivers of transmission, allowing mechanistic insight into pathogen spread and maximizing opportunities to control, many of which would not be possible from case-based investigations (Table 3)..Where it is collected, an additional major benefit of the comprehensive dataset is that it can inform mathematical models that reconstruct entire outbreaks, allowing us to estimate the mean transmission distance (previously estimated here at 95 meters) (Salje et al., 2016b).

Table 3.

Comparison of outbreak investigation approaches. ‘x’ represents a weak ability to measure the outcome of interest, ‘xx’ represents a medium ability to measure the outcome of interest and ‘xxx’ a robust ability to measure the outcome of interest.

| Outcome of each approach | Approaches |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal healthcare cases | Community cases | Community cases plus controls from same household | Community cases plus controls from other community households | |

| Case counts | x | xxx | xxx | xxx |

| Incidence | x | xx | xxx | xxx |

| Case characteristics | x | xxx | xxx | xxx |

| Case fatality proportion | xx | xxx | xxx | xxx |

| Risk factors for being a case (age/sex) | x | x | xx | xxx |

| Risk factors for being a case (other) | - | - | xx | xxx |

| Household transmission estimates | - | - | xxx | xxx |

| Spatial variability in risk | - | - | - | xxx |

Travelling outside Tangail district within the six months before the outbreak was associated with increased chikungunya fever risk. Human movement can introduce CHIKV into new areas, causing epidemics (Chretien and Linthicum, 2007). No other areas of Bangladesh were reporting outbreaks of CHIKV at this time, though outbreaks may have been missed due to poor surveillance. Although individuals of all ages were affected by chikungunya in this outbreak, incidence increased with age among females, potentially linked to increased time women spend at home compared to males, increasing their risk of being bitten by the largely home-dwelling Aedes mosquito (Salje et al., 2016b). In this outbreak, household use of mosquito coils was not protective against chikungunya, which is consistent with the findings from a recent meta-analysis on household level risk factors for dengue, which is also spread through Aedes mosquitoes (Bowman et al., 2016).

Serum samples have the potential to provide important information about the level of asymptomatic infection during an outbreak, as has previously been shown during previous CHIKV outbreaks (Salje et al., 2016a; Sissoko et al., 2008). In addition, this outbreak investigation was carried out six months after the outbreak began and community members may have been unable to reliably recall their symptoms or the date their symptoms started, particularly for milder illnesses, which may have led to an underestimation of suspected cases. Serological confirmation could help detect any missing infections. However, our study highlights how some caution needs to be taken when interpreting serological data. Firstly, while we sought to obtain blood samples from all participants, only one in five individuals agreed. We found that the probability of agreeing to provide blood depended strongly on having had chikungunya symptoms (individuals who had symptoms were more likely to provide samples). Children, women and those with a high educational level were less likely to give blood. Secondly, the sensitivity of the commercial assay we used has been estimated to be <40% in individuals where IgM is still circulating (Johnson et al., 2016) and is likely to be even lower here, as the blood draw occurred after IgM antibodies would have waned to undetectable levels for many infected individuals (Kam et al., 2012). Future studies should consider underlying biases in who is providing blood as well as considering the use of complementary IgG assays to help improve the interpretability of serological findings.

This investigation suggests that chikungunya virus has become an emerging public health problem in Bangladesh, and outbreak investigations of emerging infections often have the objective of estimating attack rates of diseases and identifying the risk factors that lead to infection. Our analysis suggests that the optimal strategy for attaining these objectives during an outbreak is to conduct case finding, testing, and data collection in communities. Many recent outbreaks of emerging infections have suffered due to a lack of detailed information about attack rates and risk for infection, due to their limited investigation strategies (Ahmed et al., 2015; Ballera et al., 2015; Khatun et al., 2015). Future investigations of emerging infection outbreaks should consider using these more intensive strategies, at least in a subset of investigations, to improve our understanding of these infections and our public health response.

Data statement

According to institutional data policy of the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (icddr,b), summary of data can be publicly displayed or can be made publicly accessible. To protect intellectual property rights of primary data, icddr,b cannot make primary data publicly available. However, upon request, Institutional Data Access Committee of icddr,b can provide access to primary data to any individual, upon reviewing the nature and potential use of the data. Requests for data can be forwarded to: Ms. Armana Ahmed,Head, Research Administration, icddr,b, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Email: aahmed@icddrb.org.

Funding

This work was supported by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, USA [cooperative agreement no: 5U01CI000628]. In addition, the Government of Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK provided core/unrestricted funding support for this work. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.111.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Ahmed S., Francis L., Ricketts R.P., Christian T., Polson-Edwards K., Olowokure B. Chikungunya Virus Outbreak, Dominica, 2014. Emerging infectious diseases. 2015;21(5):909–911. doi: 10.3201/eid2105.141813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Abdallat M.M., Payne D.C., Alqasrawi S., Rha B., Tohme R.A., Abedi G.R. Hospital-associated outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: a serologic, epidemiologic, and clinical description. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014;59(9):1225–1233. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry M., Teissier A., Roche C., Richard V., Yan A.S., Zisou K. Chikungunya outbreak, French Polynesia, 2014. Emerging infectious diseases. 2015;21(4):724–726. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward B., Barboza P., Bawo L., Bertherat E., Bilivogui P., Blake I. Ebola virus disease in West Africa--the first 9 months of the epidemic and forward projections. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(16):1481–1495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballera J.E., Zapanta M.J., de los Reyes V.C., Sucaldito M.N., Tayag E. Investigation of chikungunya fever outbreak in Laguna, Philippines, 2012. Western Pacific surveillance and response journal : WPSAR. 2015;6(3):8–11. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2015.6.1.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics . 2011. Bangladesh population and housing census 2011. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics Dhaka. Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Boore A.L., Jungk J., Russo E.T., Redd J.T., Angulo F.J., Williams I.T. Added value of a household-level study during an outbreak investigation of Salmonella serotype Saintpaul infections, New Mexico 2008. Epidemiology and infection. 2013;141(10):2068–2073. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman L.R., Donegan S., McCall P.J. Is dengue vector control deficient in effectiveness or evidence?: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury R.I., Islam M.A., Gulshan J., Chakraborty N. Delivery complications and healthcare-seeking behaviour: the Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey, 1999-2000. Health & social care in the community. 2007;15(3):254–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chretien J.P., Linthicum K.J. Chikungunya in Europe: what’s next? Lancet (London, England) 2007;370(9602):1805–1806. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61752-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- France A.M., Jackson M., Schrag S., Lynch M., Zimmerman C., Biggerstaff M. Household transmission of 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus after a school-based outbreak in New York City, April-May 2009. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010;201(7):984–992. doi: 10.1086/651145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- icddr,b First identified outbreak of chikungunya in Bangladesh. Health and Science Bulletin. 2008;7(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B.W., Russell B.J., Goodman C.H. Laboratory Diagnosis of Chikungunya Virus Infections and Commercial Sources for Diagnostic Assays. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;214(suppl 5):S471–s4. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam Y.W., Simarmata D., Chow A., Her Z., Teng T.S., Ong E.K. Early appearance of neutralizing immunoglobulin G3 antibodies is associated with chikungunya virus clearance and long-term clinical protection. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012;205(7):1147–1154. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatun S., Chakraborty A., Rahman M., Nasreen Banu N., Rahman M., Hasan S.M. An Outbreak of Chikungunya in Rural Bangladesh, 2011. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessler J., Rodriguez-Barraquer I., Cummings D.A., Garske T., Van Kerkhove M., Mills H. Estimating Potential Incidence of MERS-CoV Associated with Hajj Pilgrims to Saudi Arabia, 2014. PLoS currents. 2014;6 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.c5c9c9abd636164a9b6fd4dbda974369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewnard J.A., Ndeffo Mbah M.L., Alfaro-Murillo J.A., Altice F.L., Bawo L., Nyenswah T.G. Dynamics and control of Ebola virus transmission in Montserrado, Liberia: a mathematical modelling analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(12):1189–1195. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70995-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H.J., Qian J., Kargbo D., Zhang X.G., Yang F., Hu Y. Ebola Virus Outbreak Investigation, Sierra Leone, September 28-November 11, 2014. Emerging infectious diseases. 2015;21(11):1921–1927. doi: 10.3201/eid2111.150582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden W.H. An epidemic of virus disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952-53. II. General description and epidemiology. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1955;49(1):33–57. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(55)90081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolay B., Salje H., Sturm-Ramirez K., Azziz-Baumgartner E., Homaira N., Ahmed M. Evaluating Hospital-Based Surveillance for Outbreak Detection in Bangladesh: Analysis of Healthcare Utilization Data. PLoS medicine. 2017;14(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A., Sengupta P.G., Mondal S.K., Gupta D.N., Manna B., Ghosh S. Gender differences in healthcare-seeking during common illnesses in a rural community of West Bengal, India. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 2002;20(4):306–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salje H., Cauchemez S., Alera M.T., Rodriguez-Barraquer I., Thaisomboonsuk B., Srikiatkhachorn A. Reconstruction of 60 Years of Chikungunya Epidemiology in the Philippines Demonstrates Episodic and Focal Transmission. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2016;213(4):604–610. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salje H., Lessler J., Paul K.K., Azman A.S., Rahman M.W., Rahman M.W. How social structures, space, and behaviors shape the spread of infectious diseases using chikungunya as a case study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611391113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauerbrei W., Royston P., Binder H. Selection of important variables and determination of functional form for continuous predictors in multivariable model building. Statistics in medicine. 2007;26(30):5512–5528. doi: 10.1002/sim.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissoko D., Moendandze A., Malvy D., Giry C., Ezzedine K., Solet J.L. Seroprevalence and risk factors of chikungunya virus infection in Mayotte, Indian Ocean, 2005-2006: a population-based survey. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3066. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M.G., Costa Mda C., de Oliveira W.K., Nunes M.L., Rodrigues L.C. The Epidemic of Zika Virus-Related Microcephaly in Brazil: Detection, Control, Etiology, and Future Scenarios. American journal of public health. 2016;106(4):601–605. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamin D., Gertler S., Ndeffo-Mbah M.L. EFfect of ebola progression on transmission and control in liberia. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2015;162(1):11–17. doi: 10.7326/M14-2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.