Abstract

Introduction

The sustainability of healthcare delivery systems is challenged by ageing populations, complex systems, increasing rates of chronic disease, increasing costs associated with new medical technologies and growing expectations by healthcare consumers. Healthcare programmes, innovations and interventions are increasingly implemented at the front lines of care to increase effectiveness and efficiency; however, little is known about how sustainability is conceptualised and measured in programme evaluations.

Objectives

We aimed to describe theoretical frameworks, definitions and measures of sustainability, as applied in published evaluations of healthcare improvement programmes and interventions.

Design

Systematic integrative review.

Methods

We searched six academic databases, CINAHL, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, Emerald Management, Scopus and Web of Science, for peer-reviewed English journal articles (July 2011–March 2018). Articles were included if they assessed programme sustainability or sustained outcomes of a programme at the healthcare system level. Six reviewers conducted the abstract and full-text review. Data were extracted on study characteristics, definitions, terminology, theoretical frameworks, methods and tools. Hawker’s Quality Assessment Tool was applied to included studies.

Results

Of the 92 included studies, 75.0% were classified as high quality. Twenty-seven (29.3%) studies provided 32 different definitions of sustainability. Terms used interchangeably for sustainability included continuation, maintenance, follow-up or long term. Eighty studies (87.0%) clearly reported the timepoints at which sustainability was evaluated: 43.0% at 1–2 years and 11.3% at <12 months. Eighteen studies (19.6%) used a theoretical framework to conceptualise or assess programme sustainability, including frameworks that were not specifically designed to assess sustainability.

Conclusions

The body of literature is limited by the use of inconsistent definitions and measures of programme sustainability. Evaluations of service improvement programmes and interventions seldom used theoretical frameworks. Embedding implementation science and healthcare service researchers into the healthcare system is a promising strategy to improve the rigour of programme sustainability evaluations.

Keywords: organisation of health services, health policy, change management, quality in health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a clinical librarian to capture the diversity of healthcare programmes, study methodologies and study settings.

Regular team meetings, verification of data extraction accuracy and quality assessment of included publications enhanced the rigour of the review.

The review was limited to peer-reviewed articles and excluded programme evaluations published in the grey literature.

The focus on outcomes at the healthcare systems level meant that programmes that assessed patient and/or community outcomes only, were excluded from this review.

Introduction

Background

Healthcare systems across the world strive to provide safe, high-quality care and deliver the best possible health outcomes for the populations they serve. At the same time, fiscal constraints necessitate the delivery of healthcare in an efficient and cost-effective way.1 This creates a challenge to the sustainability of healthcare systems globally.2 3 Lead international agencies, including the World Health Organization, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and the World Economic Forum, have recently highlighted significant threats to the sustainability of healthcare system performance.1 3 4 Ageing populations and the rapidly increasing burden of chronic conditions also pose challenges to healthcare system sustainability.5–7 The introduction of new medical technologies, including new diagnostic tests, new drugs, medical equipment and digital healthcare services,8 as well as a growing ‘consumer culture’, have led to demands for higher standards of patient safety and quality of care and lower costs.9 At the same time, the level of wasteful spending on low-value care has remained static, at approximately 30%, while high-value care which aligns with level I evidence or best-practice consensus guidelines accounts for approximately 60% of delivered care and has done for two decades.10–15

Sweeping policy and healthcare system ‘big bang’ reforms are relatively rare, mainly because they require enormous efforts to mobilise multiple stakeholders who work within entrenched cultures, structures and approaches that make up complex healthcare systems.16–19 Much of the change implementation to improve healthcare system sustainability occurs closer to the front lines of care, through innovative projects, improvement programmes and interventions, referred to as ‘programmes’ from this point forward.

To maximise the benefits of programme innovation in healthcare, we need the ability to rigorously assess whether programmes are adaptable to real-world settings, and sustainable beyond the programme trial period.20 Stirman et al’s 2012 systematic review of the sustainability of implemented healthcare programmes reported that few of the included studies that were published before June 2011 provided a definition of sustainability.21 The authors considered articles in which studies assessed the continuation of programmes after initial implementation efforts, staff training periods or funding had ended.21 They found that when defining sustainability, the majority of included studies referred to Scheirer’s definition22 which is based on the work of Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone.23 Scheirer proposed three levels of analysis for programme sustainability: (1) Individual level: continuing to deliver beneficial services (outcomes) to consumers; (2) Organisational level: maintaining the programme and/or its activities, even if modified and (3) Community level: maintaining the capacity of a community to deliver programme activities.22 In a subsequent paper, Scheirer and Dearing defined sustainability as ‘the continued use of program components and activities for the continued achievement of desirable program and population outcomes.’(p2060)24

More recently, Moore et al25 proposed five constructs for the assessment of programme sustainability: (1) following a defined period of time, (2) a continuation of a programme and/or (3) the maintenance of individual behavioural change, (4) evolution or adaption of the programme, and individual behavioural change may occur while (5) continuing to produce benefits for individuals/systems. In a review published the following year, Lennox et al26 found continuation of programme activities and continued health benefits as the most commonly reported sustainability constructs.26 Guided by Stirman et al21 and previously established definitions, for this current review, sustainability was conceptualised as the continuation of programme or programme components, or the continuation of outcomes, after initial implementation efforts, staff training or funding has ended. In terms of outcomes, our review was concerned with healthcare system outcomes (Scheirer’s organisation level of analysis), rather than patient or community outcomes.22

In addition to the limited use of operationalised definitions, Stirman et al21 also found that included studies often lacked methodological rigour and seldom used theoretical frameworks or defined measures to evaluate programme sustainability.21 Although theories and frameworks abound, with new ones continually proposed,26 there is limited recent information about the application of theories and frameworks in the healthcare system to underpin the assessment of system-level sustainability of implemented programmes.

Objectives

With an increasing emphasis on the potential threats to healthcare system sustainability as an impetus, we aimed to describe to what extent studies of healthcare improvement programmes, as implemented in the healthcare delivery system, report on programme sustainability. We also aimed to determine which theoretical frameworks have been applied, and how sustainability is defined, conceptualised and measured.

The current systematic integrative review builds on the work of Stirman et al21 and is part of a larger project investigating healthcare system sustainability.27 A detailed account of barriers and facilitators to the sustainability of implemented healthcare programmes will be reported separately.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The published protocol for this review27 can be found at the following web address: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/7/11/e018568. Since publishing the protocol, we realigned our focus with Schreirer’s organisational level analysis as we were interested in system and organisational level outcomes for implemented programmes in the healthcare delivery system. Modifications to our protocol are explained and justified in the corresponding sections.

Search strategy

This review was carried out in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses statement (PRISMA).28 The search strategy was developed by KL, JH, LT, EM and a clinical librarian (Mary Simons). Six academic databases were searched: CINAHL, Embase, Ovid MEDLINE, Emerald Management, Scopus and Web of Science (see box 1 for search strategy example). Emerald Management was added after the publication of the study protocol to find publications related to management or operations. To capture relevant articles not discovered by database searches, we used a snowballing approach to manually search reference lists of systematic reviews.

Box 1. Search strategy example: Embase.

(Sustainab* OR continuation OR continual OR institutionali* OR resilien* or durab* OR viab* OR stability OR stable OR persist* OR maintenance OR routin*).ti, ab.

exp programme sustainability/.

(Improve* OR innovation OR reform* OR intervention OR programme* OR strateg* OR project OR plan OR change management).ti, ab.

health programme/ or health promotion/ or organisation/.

healthcare delivery/ or integrated healthcare system/.

1 OR 2.

3 OR 4.

5 AND 6 AND 7.

-

limit eight to (human and English language and yr=

“2011 -Current” AND (article or article in press OR “review”) AND journal).

-

remove duplicates from 9.

* Indicates truncation.

Study selection

Data were downloaded into EndNote V8 and duplicates removed. Table 1 outlines the selection criteria applied when reviewing abstracts and full-text publications. To establish inter-rater reliability, six reviewers (KL, LT, HA, JH, GL and EM) completed a blinded review of a random 5% sample of abstracts. Any discrepancies between reviewers’ decisions were discussed by the author group, with JB and YZ acting as arbitrators. The remaining publications were randomly allocated between the reviewers who reviewed study abstracts. Rayyan, a web and mobile app for systematic reviews,29 was used for the blinded and full abstract review. Publications that met the inclusion criteria were subject to a full-text review using the selection criteria.

Table 1.

Selection criteria

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| 1. Language | English language | Languages other than English |

| 2. Types of publications | Peer-reviewed journal articles | Posters, conference proceedings, thesis dissertations |

| 3. Types of research | Primary empirical research including secondary analyses of data | Systematic reviews, protocols, grey literature, and ‘lessons learned’ documents (unless presenting empirical data analysis) |

| 4. Publication data | Published July 2011–March 2018 | Published before July 2011 or after March 2018 |

| 5. Setting | Healthcare settings including hospitals, primary care, residential aged care, mental health and community health | Settings other than healthcare, such as environmental sustainability and primary/high school education |

| 6. Evaluation | Evaluated programmes, interventions or change strategies, including studies of multiple projects | Models of care, evaluations of new centres, and government reforms or policies, for example, health insurance |

| 7. Sustainability | Assesses sustainability of a programme from a systems or organisational view point: | Studies that reported on outcomes for patients or clients only, broad public health programmes or community initiatives that did not report on system-based or organisational outcomes or impacts, pilots and studies of early implementation |

| (A) Evaluation of a programme after funding has ended or after the initial training or implementation phase | ||

| (B) Explicitly assesses sustainability, for example, stakeholders’ views of sustainability even if a programme is in its implementation phase | ||

| (C) Longitudinal studies consisting of follow-up assessments or evaluations conducted over multiple timepoints | ||

| 8. Systems outcomes | Focus is on changes or improvements to the healthcare system | Public health or prevention programmes, for example, physical activity, immunisation, smoking, contraceptive use, screening; patient-based outcomes only; community-based outcomes only; and studies of cost-effectiveness if only projected or hypothetical savings—not actual cost-savings |

Data collection processes and data items

Data were extracted by reviewers into a purpose-designed Microsoft Excel Spreadsheet. Data items are summarised in box 2. These categories were derived from an initial review of key papers on the topic of healthcare sustainability. During regular team meetings, the categories were further refined, and descriptions were amended as the team progressed with the full-text review and data extraction. Data were extracted on study characteristics; definitions and terminology; programme evaluations, funding and evolution; theoretical frameworks; and methods and tools used to assess programme sustainability (box 2).

Box 2. Data items extracted from included publications.

Study characteristics

Study design

Method

Setting type

Country

Description of the programme

Defining sustainability

Definitions

Terminology

Conceptualising sustainability

Evaluation of sustainability: whether the focus of the evaluation was (A) the sustainability of the programme, (B) the continuation of systems-based outcomes or (C) both A and B

Funding of the programme

Evaluation of timepoints

Evolution of the programme

Theoretical frameworks

Name of framework

Framework details

How the framework was used

Stage of framework use (programme design, implementation or evaluation)

Assessing sustainability

Methods used

Tools used

We recorded the timepoints at which the continuation of the programme or systems outcomes were assessed. We included evaluations of programmes which were deemed to have continued and reported system or organisational outcomes after the initial implementation phase, staff training or programme funding had ended. The reporting of multiple evaluation timepoints in many of the publications was ambiguous and therefore not reported in our review. For articles reporting on more than one programme, the longest time frame was recorded. ‘Evolution of programmes’ referred to whether the programme had been changed, modified or adapted from its initial design.

Data analysis and synthesis

Our analysis and synthesis was guided by Miles and Huberman30 and Whittemore and Knafl.31 The data reduction stage involved extracting data using the purpose-designed Excel spreadsheet and frequency counting techniques. Data were displayed using matrices to aid comparisons and synthesis across studies. Data were compared and synthesised to summarise study characteristics, definitions of sustainability and terminology, healthcare programme features (eg, funding), the use of theoretical frameworks and assessments of sustainability. Verification of the accuracy and meanings of the extracted data was undertaken by KL and LT, with YZ and JB arbitrating when questions arose.

Quality assessment

The quality of individual studies was assessed by KL, LT, HA, JH and GL using Hawker’s Quality Assessment Tool.32 This tool comprises the following domains: abstract and title; introduction and aims; method and data; sampling; data analysis; ethics and bias; results; transferability (generalisable); and implications and usefulness. An overall quality rating of low, medium or high was assigned to each study based on Lorenc et al.33 The reviewers first completed a blinded quality assessment of 6% of studies before each assessing a proportion of the remainder. Although in our protocol we planned to use the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool to assess risk of bias, Hawker’s Quality Assessment Tool was deemed more appropriate as it is specifically designed for assessing quality across different study methodologies.

Patient and public involvement

The NHMRC Partnership Centre in Health System Sustainability (PCHSS) includes among its members the Consumers Health Forum of Australia (CHF). Members of the CHF were present at meetings of the PCHSS and had opportunity to comment on this study.

Results

Study selection

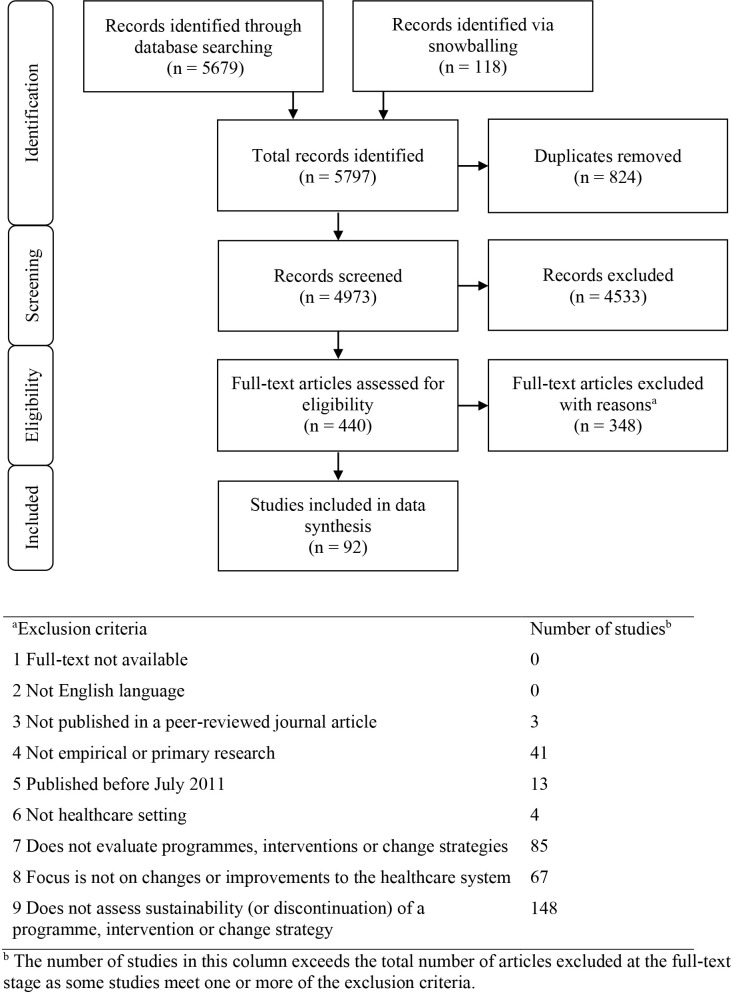

The search of academic databases identified 5679 records, with an additional 118 records obtained through snowballing. The agreement rate between the six reviewers of the blinded 5% abstract review was 92%. This high rate, along with a high proportion of exclusion decisions, had the potential to reduce the value of Fleiss’ kappa, resulting in a misrepresentative kappa score.34 To account for this, Brenann-Prediger’s kappa was calculated at 0.84 (95% CI: 0.78 to 0.90).35 The results of the review strategy are detailed in figure 1. After removal of duplicates, the abstracts and titles of 4973 records were screened using the selection criteria. Four hundred and forty records were retained for full-text review, yielding 92 articles for inclusion in data synthesis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram28 summarising the review process and reasons for article exclusion.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Most included studies used quantitative methods and had longitudinal study designs (table 2). Sixty-nine studies (75.0%) were classified as high quality, 20 (21.7%) were medium quality and 3 (3.3%) were rated as low quality (online supplementary file 1). Studies came from 33 countries. The studies covered high-income (n=10, 30.3%), upper-middle-income (n=5, 15.1%), lower-middle-income (n=8, 24.2%) and low-income (n=10, 30.3%) countries as classified by the World Bank36 (table 2). Almost half of the studies (n=44, 47.8%) originated from North America, and of these, 36 (81.8%) were conducted in the USA. The second-most common setting was the UK (n=9, 9.8%), followed by the Netherlands (n=8, 8.7%) and Canada (n=7, 7.6%).

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| No of studies | % | |

| Method | ||

| Quantitative | 47 | 51.1 |

| Qualitative | 24 | 26.1 |

| Mixed-methods/qualitative and quantitative components | 21 | 22.8 |

| Study design | ||

| Longitudinal | 39 | 42.4 |

| Case study | 25 | 27.2 |

| Cross-sectional | 12 | 13.0 |

| Randomised controlled trial | 9 | 9.8 |

| Quasi-experimental | 6 | 6.5 |

| Natural experiment | 1 | 1.1 |

| Geographical region* | ||

| North America | 44 | 47.8 |

| Europe | 25 | 27.2 |

| Africa | 18 | 19.6 |

| Asia | 8 | 8.7 |

| South America | 3 | 3.3 |

| Oceania | 3 | 3.3 |

| No of countries | % | |

| World Bank income group classification | ||

| Low income | 10 | 30.3 |

| Lower-middle income | 8 | 24.2 |

| Upper-middle income | 5 | 15.1 |

| High income | 10 | 30.3 |

*Four studies were conducted in more than one country and the percentage was adjusted accordingly.

bmjopen-2019-036453supp001.pdf (126.7KB, pdf)

Defining sustainability

Definitions

Over half of studies (n=53, 57.6%) explicitly referred to sustainability as part of the study aim. Only 27 studies (29.3%) defined sustainability, whether this was in reference to an established definition, a composite of established definitions or authors’ own definition (see table 3). Thirty-two definitions were identified across the included studies. Nine pre-existing definitions were cited by multiple studies. In four of the studies, the authors provided their own definitions (table 3). Collectively, the two most frequently cited definitions from Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone’s23 and Scheirer and Dearing’s24 work were cited by 15 of the 27 studies (55.6%) that defined sustainability. There were 19 additional previously published definitions identified, each cited by single studies.

Table 3.

Definitions of sustainability and terminology use

| No of studies | %* | |

| Defined sustainability | ||

| Yes | 27 | 29.3 |

| No | 65 | 70.7 |

| No of studies† | %†‡ | |

| Definition | ||

| Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone23 | 10 | 37.0 |

| Scheirer and Dearing24 | 5 | 18.5 |

| Pluye et al77 | 4 | 14.8 |

| Scheirer22 | 3 | 11.1 |

| Buchanen et al78 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Stirman et al21 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Slaghuis et al64 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Procter et al79 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Gruen et al52 | 2 | 7.4 |

| Other pre-existing definitions§ | 19 | 70.4 |

| Authors’ own definition | 4 | 14.8 |

| Terminology | ||

| Sustainability/sustainable/sustainably | 70 | 76.1 |

| Sustain/sustained/sustaining/sustainment/sustainers | 69 | 75.0 |

| Continuation/continues/continued/continuance/continue | 47 | 51.1 |

| Maintenance/maintained | 46 | 50.0 |

| Follow-up/followed up | 43 | 46.7 |

| Long erm/longer term | 42 | 45.7 |

| Adoption/adopted/adopt/adopters | 36 | 39.1 |

| Post/after/following: trial/intervention/phase/programme/training/design/inception/project/initiation/establishment/competition/assessment/test/funding/enrolment |

31 | 33.7 |

| Post-implementation/after implementation/following implementation | 25 | 27.2 |

| Routine/routinisation/routinely | 22 | 23.9 |

| Institutionalised/institutional/ institutionalisation/institutionalising | 13 | 14.1 |

| Discontinuation/discontinued/discontinuity/not continued | 13 | 14.1 |

| Durability/durable | 3 | 3.3 |

| Scalability/scale-up | 2 | 2.2 |

| Other | 3 | 3.3 |

*As a proportion of total studies.

†The number of studies and associated percentage exceeds the total number of included studies and 100%, respectively, as some studies referred to more than one definition or term.

‡As a proportion of studies defining sustainability.

§Definitions each cited by single studies.

Terminology

The terminology used to describe sustainability varied greatly (table 3). The most commonly used terms were a variation of ‘sustainability’ or ‘sustained’, followed by ‘continuation’, ‘maintenance’, ‘follow-up’ and ‘long term’.

Conceptualising sustainability

Evaluation of sustainability

Over a third of studies (n=33, 35.9%) focused on the sustainability of a programme or its components. Thirty-seven studies (40.2%) looked at the continuation or improvement of healthcare systems outcomes, such as length of stay, hospital costs, quality of care and hand hygiene compliance. Twenty-two studies (23.9%) examined both the sustainability of programmes and systems outcomes.

Funding of programmes

A quarter of studies (n=22, 23.9%) specified whether funding had ended (n=12, 13.0%) or was ongoing (n=10, 100.9%), and two studies (2.2%) indicated that funding was not applicable. Sixteen studies (17.4%) did not report funding. The remaining 52 studies (56.5%) referred to funding or specified funding organisation(s); however, it was not clear what the length of funding was or whether funding had ended or was ongoing.

Timepoints at which sustainability was assessed

The majority of studies (n=80, 87.0%) provided a clear time frame between the end of initial implementation, staff training or funding and the final evaluation timepoint. An additional 10 studies (10.9%) specified that evaluations occurred post-implementation; however, a final clear evaluation timepoint was not provided. Two programmes (2.2%) were still in their implementation phase but were included in this review as stakeholders were interviewed about the future sustainability of the programme. The evaluation periods from the 80 studies providing clear final evaluation timepoints ranged from several months to years, with the longest evaluations reported at 10,37 1238 and 16 years.39 The mean evaluation period was 40.7 months. For most studies (n=34, 42.5%), the final evaluation timepoint was between 1 and 2 years post-implementation, post-training or post-funding. Nine studies (11.3%) used an evaluation time of less than a year.

Only 11 of the 92 studies (12.0%) reported that evaluation occurred after initial programme funding had ended. Of these 11, 9 studies (81.8%) evaluated programme sustainability, 1 (9.1%) evaluated the continuation of systems-level outcomes and 1 (9.1%) evaluated the sustainability of both programme and outcomes. Eight of the 11 studies (72.7%) clearly specified the evaluation period after funding had ended, ranging from 8 months to 6 years (mean=35 months). For the other three studies (27.3%), it was not clear when the funding ended in relation to the evaluation.40–42

Evolution of programme

Thirty-four studies (34.0%) described evolution, adaptation or modification of programmes, which included for example, flexibility of the programme,43 adjustments to suit local context,44–46 incorporating feedback from front line staff,47 48 evolution of the programme over time49 50 and establishing a dedicated team responsible for continuous monitoring and making adaptations to programmes.51

Theoretical frameworks

Eighteen of the 92 included studies (19.6%) used a sustainability-related theoretical framework (online supplementary file 2). Fourteen of the 18 studies using a framework (77.8%) made explicit reference to sustainability in the study aims (online supplementary file 2). The other four studies (22.2%) reported on sustainability, despite not referring to the concept in the aims. Some frameworks were purpose-designed to evaluate sustainability (eg, Gruen et al’s dynamic model of health programme sustainability).52 Other frameworks were originally designed for other purposes and not for the assessment of sustainability, for example, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research53; Atun et al’s conceptual framework for analysing integration of targeted health interventions into health systems54; or Greenhalgh et al’s Conceptual Model for Considering the Determinants of Diffusion, Dissemination, and Implementation of Innovations in Health Service Delivery and Organization.55 The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance framework56 was designed to examine success across the life-cycle of a programme, including its sustainability (maintenance), and was used by two studies (online supplementary file 2).

bmjopen-2019-036453supp002.pdf (82.3KB, pdf)

Reasons for using frameworks

Seventeen of the 18 studies reported using a framework (94.4%) to underpin programme evaluation, with three key purposes: (1) to assess quantitative data related to outcomes; (2) to frame interview guides and (3) to inform, structure, map or verify qualitative findings. Six studies (33.3%) used frameworks for multiple purposes (online supplementary file 2).

Only 1 of the 18 studies (5.6%) used a framework to support implementation. Licskai et al used the Canadian Institutes of Health Research ‘knowledge-to-action’ framework to implement an asthma guidelines programme.57 As part of this cycle, a key action phase was ‘sustained knowledge use’. No studies reported using frameworks to support the design of programmes.

Assessing sustainability

Methods used

The most common research method used (n=46, 50.0%) to measure sustainability was the analysis of routinely collected data by healthcare organisations (eg, patient length of stay, admissions/readmission, financial data). Interviews were used in 41 studies (44.6%) and surveys in 28 (30.4%) studies. Other methods included checklists, observations, cost-effectiveness evaluations and focus group discussions. Forty-six of the studies (50.0%) used more than one method, including mixed-methods approaches.

Tools used

A small proportion of studies (n=6, 6.5%) used purpose-designed tools to evaluate sustainability. Three studies58–60 used the National Health Service (NHS) Sustainability Model and associated index.61 Despite using the same tool, the three studies reported different names: the British NHS Sustainability Index, the NHS Sustainability Survey and the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Sustainability Model self-assessment tool. Two studies62 63 used the Routinisation Instrument developed by Slaghuis et al64 and one study65 used Goodman’s Level of Institutionalisation Scales.66

Discussion

We need health systems and programmes that are built to last, but studies purporting to assess such systems and programmes lack definitional consistency and rigour. Our study provides a unique summary of the current application of theoretical concepts and frameworks to assess the sustainability of implemented healthcare programmes. Surprisingly, over 40% of studies describing programmes that referred to sustainability or related concepts in the title, abstract or keywords had to be excluded at full-text review because they did not assess or report on programme sustainability. Just over 57% of studies explicitly referred to sustainability in their aims, while only 29% of studies provided an operational definition of programme sustainability. This is even lower than the 35% of studies included in Stirman’s review published in 2012,21 but higher than Moore et al’s 2017 review on definitions of sustainability, where only 11.5% of included articles provided a definition.25 Unlike Stirman and colleagues,21 the majority of the studies in our review that provided a definition of sustainability cited a pre-existing definition in the literature suggesting that evaluators are increasingly looking to the literature for definitions of programme sustainability.

The lack of a unified definition of sustainability across the literature manifested in our review through a 16-year variation in timepoints at which the authors assessed the sustainability of their programmes or programme outcomes. Of the 80 studies reporting a clear final evaluation timepoint, the majority (n=34, 42.5%) measured sustainability of a programme or continuation of outcomes 1–2 years after initial implementation, staff training or funding ended. This was similar to the 64% reported by Stirman et al.21 Just over 11% (n=9) of the 80 studies used an evaluation time of less than a year which is higher than the 6% reported by Stirman et al.21 Furthermore, some studies assessed programme sustainability only a few months after the end of initial implementation or programme funding.43 67 68 While programmes and approaches to implementation may differ, time is an important construct of sustainability, and it must be clearly articulated and justified as part of an operational definition of sustainability before undertaking an evaluation.25 The timing of a sustainability evaluation is dependent on the individual programme, outcomes of interest and whether sustainability is viewed as an outcome or as a process.25 26 Lennox et al’s systematic review, investigating approaches to healthcare sustainability evaluation, found that the measurement over time approach was used in the majority of studies.26 Although we attempted to identify studies that assessed sustainability at multiple timepoints, this was methodologically impossible as the timepoints reported were varied and often ambiguous. Formative evaluation feedback loops are thought to be essential to support successful programme implementation processes,69 however, only about a third of our included studies reported on some aspects of programme evolution, adaptation or modification, with ongoing monitoring and evaluation running alongside the implementation.

Stirman et al argued that researchers should be guided by appropriate theoretical frameworks to advance healthcare programme sustainability research.21 Many theoretical frameworks have been published to support the implementation, monitoring and assessment of healthcare programme sustainability.26 Our review suggests that in recent years, there has been little improvement in the use of theoretical frameworks to underpin assessment of the sustainability of healthcare programmes implemented in the healthcare delivery system. Stirman et al reported that 16% of studies included in their review used a theoretical framework21 and approximately 20% of our included studies did so.21 Furthermore, studies that applied frameworks mostly reported doing so at the evaluation stage rather than at the inception of programme design or implementation. This post hoc approach limits the rigour and validity of evaluation results for these programmes.70 Robust comparisons across studies were difficult because only 6.5% of studies used published tools to assess sustainability. Although three studies used the same tool (The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement Sustainability Model), they published different names for this tool, further challenging the ability to compare across studies.

Study implications

Our review revealed a lack of consistency in the way sustainability is defined, conceptualised, assessed and reported on. Furthermore, we found little improvement since Stirman et al’s review in 2012, with ongoing limited use of sustainability-related theoretical frameworks and assessment tools. We recommend that future evaluations of programmes mobilise operational definitions of sustainability, theoretically rigorous frameworks, clear and appropriate timepoints and validated assessment tools such as the Routinisation Instrument64 to evaluate sustainability of healthcare programmes. This will build a needed evidence base to support policy and investment decisions about scaling up and spreading healthcare programmes, and for them ultimately to be longer lasting.

A concerted effort is needed to move theory into practice and to support ongoing engagement between the healthcare sector and implementation science and healthcare services researchers.71 Embedding healthcare services researchers with skills in implementation science and systems science expertise in the healthcare system is one potential solution.72 Closer links at organisational level between academic and research institutes and organisations at the front lines of the healthcare system may also be helpful.

Healthcare delivery improvement programmes are considered among the essential building blocks of sustainable healthcare systems.73 The current lack of evidence consistency about the sustainability of implemented improvement programmes will inevitably limit the understanding of broader concepts such as social, economic and environmental benefits, increasingly expected from sustainable healthcare systems.74 Although artificial intelligence (AI) is also increasingly proposed as one of the solutions to support healthcare system sustainability, our review did not pick up publications in AI, possibly because this is an emerging field. We expect that future reviews will build on currently emerging work in AI75 76 to incorporate evaluations of implemented AI solutions and their contribution to health system sustainability.

Strengths and limitations

The search strategy was designed in collaboration with a medical librarian to enable us to capture the diversity of healthcare programmes and the disparate nature of the study methodologies and settings. We ensured our methods were rigorous through team discussions and a double-blinded sample review to ensure consistency of study inclusion and interpretation. Regular team meetings were necessary to resolve queries and divergence of opinions about which healthcare programmes to include and what constitutes sustainability. Our review is limited to English-language studies published in the peer-reviewed literature; however, we know that many healthcare programme evaluations are not published in the public domain or are published in the grey literature. The literature search was conducted in March 2018, and therefore, this review does not include articles published in the last 2 years. We intend to review this topic again in 2 years’ time to assess the progression of research on health systems sustainability. We used a systems sustainability lens for our review and programmes that assessed patient and community outcomes only were excluded; we acknowledge that positive system outcomes do not necessarily translate to positive patient or community outcomes. Additional analyses are needed to describe the complex inter-relationships among patient, community and system aspects of healthcare programme sustainability.

Conclusions

Our review uncovered lack of conceptual clarity, poor consistency of purpose and inconsistencies in defining and assessing the sustainability of programmes implemented in healthcare systems. Many studies discussed the sustainability of healthcare programmes but failed to adequately define or measure programme sustainability. Furthermore, few studies reported using sustainability-related frameworks to support programme evaluations. There is a need therefore to upskill and build capacity in teams that design, implement and evaluate healthcare programmes to ensure conceptual clarity and rigorous methodology. Consistent and unified definitions of programme sustainability are needed to enable comparisons among evaluation studies and to generate a systematic evidence base on which to make decisions about programme sustainability. The effectiveness of embedding implementation science and healthcare services researchers into the healthcare system to form collaborative teams with decision-makers and clinicians should be trialled.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Simons, clinical librarian, Macquarie University, who assisted with the development of the search strategy, and Johanna Holt for helping to refine the selection criteria. The authors also thank Hsuen P Ting, biostatistician at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University, for calculating the kappa coefficient for the blinded 5% sample abstract review and Dr Margie Campbell, Research Fellow, Centre for Health Economics Research and Evaluation, University of Technology Sydney, for identifying additional articles to include in the review via snowballing techniques.

Footnotes

Twitter: @YvonneZurynski

Contributors: JB conceptualised the study and led the team’s work. KL, LT, JH and EM developed the search strategy. KL, LT, JH, HA, GL and EM conducted the abstract review, full-text review and data extraction, with JB and YZ acting as arbitrators. The quality assessment of included articles was conducted by KL, LT, JH, HA and GL. KL and LT undertook the synthesis of data. KL, LT and YZ wrote the draft manuscript, with all authors providing feedback and approving the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the NHMRC Partnership Centre in Health System Sustainability (Grant ID 9100002) and NHMRC Investigator Grant APP1176620.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not directly involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study.

References

- 1.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Tackling wasteful spending on health. Paris, France: OECD, 2017. https://www.oecd.org/health/tackling-wasteful-spending-on-health-9789264266414-en.htm [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braithwaite J, Mannion R, Matsuyama Y, Healthcare systems: future predictions for global care. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Economic Forum Sustainable health systems. Visions, strategies, critical uncertainties and scenarios. Geneva, Switzerland: WEF, 2013. https://www.weforum.org/reports/sustainable-health-systems-visions-strategies-critical-uncertainties-and-scenarios [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Everybody’s business. Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHO’s framework for action. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2007. https://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braithwaite J, Vincent C, Nicklin W, et al. Coping with more people with more illness. Part 2: new generation of standards for enabling healthcare system transformation and sustainability. Int J Qual Health Care 2019;31:159–63. 10.1093/intqhc/mzy236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization World report on ageing and health 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2015. https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare Australia’s health 2018: In brief. Canberra, Australia: AIHW, 2018. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-health/australias-health-2018-in-brief/contents/about [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saini V, Brownlee S, Elshaug AG, et al. Addressing overuse and underuse around the world. Lancet 2017;390:105–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32573-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Evidence-Based Medicine, Yong PL, Saunders RS, Olsen LA . Consumers-directed policies : The healthcare imperative: lowering costs and improving outcomes: workshop series summary. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine (US), 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, et al. CareTrack: assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Med J Aust 2012;197:100–5. 10.5694/mja12.10510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braithwaite J. Changing how we think about healthcare improvement. BMJ 2018;361:k2014. 10.1136/bmj.k2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2635–45. 10.1056/NEJMsa022615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangione-Smith R, DeCristofaro AH, Setodji CM, et al. The quality of ambulatory care delivered to children in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007;357:1515–23. 10.1056/NEJMsa064637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braithwaite J, Hibbert PD, Jaffe A, et al. Quality of health care for children in Australia, 2012-2013. JAMA 2018;319:1113–24. 10.1001/jama.2018.0162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferlie E, Montgomery K, Reff A, et al. Patient safety and quality : The Oxford handbook of health care management. Oxford. UK: Oxford University Press, 2016: 325–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lipsitz LA. Understanding health care as a complex system: the foundation for unintended consequences. JAMA 2012;308:243–4. 10.1001/jama.2012.7551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Economic Forum Misaligned stakeholders and health system underperformance. Cologny, Switzerland: WEF, 2016. https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/misaligned-stakeholders-and-health-system-underperformance [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toth F. Integration vs separation in the provision of health care: 24 OECD countries compared. Health Econ Policy Law 2020;15:160–72. 10.1017/S1744133118000476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Caring for quality in health: lessons learnt from 15 reviews of health care quality. Paris, France: OECD, 2017. https://www.oecd.org/health/caring-for-quality-in-health-9789264267787-en.htm [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The sustainability of evidence-based interventions and practices in public health and health care. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:55–76. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stirman SW, Kimberly J, Cook N, et al. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: a review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement Sci 2012;7:17. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheirer MA. Is sustainability possible? A review and commentary on empirical studies of program sustainability. Am J Eval 2005;26:320–47. 10.1177/1098214005278752 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shediac-Rizkallah MC, Bone LR. Planning for the sustainability of community-based health programs: conceptual frameworks and future directions for research, practice and policy. Health Educ Res 1998;13:87–108. 10.1093/her/13.1.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheirer MA, Dearing JW. An agenda for research on the sustainability of public health programs. Am J Public Health 2011;101:2059–67. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore JE, Mascarenhas A, Bain J, et al. Developing a comprehensive definition of sustainability. Implement Sci 2017;12:110. 10.1186/s13012-017-0637-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lennox L, Maher L, Reed J. Navigating the sustainability landscape: a systematic review of sustainability approaches in healthcare. Implement Sci 2018;13:27. 10.1186/s13012-017-0707-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braithwaite J, Testa L, Lamprell G, et al. Built to last? the sustainability of health system improvements, interventions and change strategies: a study protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018568. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile APP for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles MB, Huberman AM, et al. Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs 2005;52:546–53. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hawker S, Payne S, Kerr C, et al. Appraising the evidence: reviewing disparate data systematically. Qual Health Res 2002;12:1284–99. 10.1177/1049732302238251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Whitehead M, et al. Crime, fear of crime and mental health: synthesis of theory and systematic reviews of interventions and qualitative evidence. Public Health Res 2014;2:1–398. 10.3310/phr02020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:543–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90158-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gwet KL. Handbook of inter-rater reliability: the definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among Raters. 4th edn Gaithersburg, MD: Advanced Analytics, LLC, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Bank World bank country and lending groups. Washington, DC: world bank, 2019. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul DL, McDaniel RR. Facilitating telemedicine project sustainability in medically underserved areas: a healthcare provider participant perspective. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:148. 10.1186/s12913-016-1401-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oliveira SRA, Medina MG, Figueiró AC, et al. Strategic factors for the sustainability of a health intervention at municipal level of Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 2017;33:e00063516. 10.1590/0102-311X00063516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorensen TD, Pestka D, Sorge LA, et al. A qualitative evaluation of medication management services in six Minnesota health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016;73:307–14. 10.2146/ajhp150212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Compton MT, et al. Budget impact and sustainability of medical care management for persons with serious mental illnesses. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1171–8. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11010071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.MacLean S, Berends L, Mugavin J. Factors contributing to the sustainability of alcohol and other drug interventions in Australian community health settings. Aust J Prim Health 2013;19:53–8. 10.1071/PY11136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seppey M, Ridde V, Touré L, et al. Donor-funded project's sustainability assessment: a qualitative case study of a results-based financing pilot in Koulikoro region, Mali. Global Health 2017;13:86–100. 10.1186/s12992-017-0307-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bridges J, May C, Fuller A, et al. Optimising impact and sustainability: a qualitative process evaluation of a complex intervention targeted at compassionate care. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:970–7. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rubin FH, Neal K, Fenlon K, et al. Sustainability and scalability of the hospital elder life program at a community hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:359–65. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03243.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brewster AL, Curry LA, Cherlin EJ, et al. Integrating new practices: a qualitative study of how hospital innovations become routine. Implement Sci 2015;10:168. 10.1186/s13012-015-0357-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh M, Gmyrek A, Hernandez A, et al. Sustaining screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment (SBIRT) services in health-care settings. Addiction 2017;112 Suppl 2:92–100. 10.1111/add.13654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hovlid E, Bukve O, Haug K, et al. Sustainability of healthcare improvement: what can we learn from learning theory? BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:235. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rask KJ, Gitomer RS, Spell NO, et al. A two-pronged quality improvement training program for leaders and frontline staff. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:147–153. 10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Regagnin DA, da Silva Alves DS, Maria Cavalheiro A, et al. Sustainability of a program for continuous reduction of catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Am J Infect Control 2016;44:642–6. 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.11.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King K, Christo J, Fletcher J, et al. The sustainability of an Australian initiative designed to improve interdisciplinary collaboration in mental health care. Int J Ment Health Syst 2013;7:10. 10.1186/1752-4458-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agarwal HS, Saville BR, Slayton JM, et al. Standardized postoperative handover process improves outcomes in the intensive care unit: a model for operational sustainability and improved team performance*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2109–15. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182514bab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gruen RL, Elliott JH, Nolan ML, et al. Sustainability science: an integrated approach for health-programme planning. Lancet 2008;372:1579–89. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61659-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ament SMC, Gillissen F, Maessen JMC, et al. Sustainability of short stay after breast cancer surgery in early adopter hospitals. Breast 2014;23:429–34. 10.1016/j.breast.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atun R, de Jongh T, Secci F, et al. Integration of targeted health interventions into health systems: a conceptual framework for analysis. Health Policy Plan 2010;25:104–11. 10.1093/heapol/czp055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, et al. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q 2004;82:581–629. 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, et al. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns 2001;44:119–27. 10.1016/S0738-3991(00)00186-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Licskai C, Sands T, Ong M, et al. Using a knowledge translation framework to implement asthma clinical practice guidelines in primary care. Int J Qual Health Care 2012;24:538–46. 10.1093/intqhc/mzs043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ford JH, Krahn D, Wise M, et al. Measuring sustainability within the Veterans administration mental health system redesign initiative. Qual Manag Health Care 2011;20:263–79. 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3182314b20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kastner M, Sayal R, Oliver D, et al. Sustainability and scalability of a volunteer-based primary care intervention (health TAPESTRY): a mixed-methods analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:514–34. 10.1186/s12913-017-2468-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mahomed OH, Asmall S, Voce A. Sustainability of the integrated chronic disease management model at primary care clinics in South Africa. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2016;8:e1–7. 10.4102/phcfm.v8i1.1248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maher L, Gustafson D, Evans A. Nhs sustainability model and guide London, UK: NHS improvement, 2017. Available: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/Sustainability-model-and-guide/

- 62.Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. Short and long term improvements in quality of chronic care delivery predict program sustainability. Soc Sci Med 2014;101:148–54. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Makai P, Cramm JM, van Grotel M, et al. Labor productivity, perceived effectiveness, and sustainability of innovative projects. J Healthc Qual 2014;36:14–24. 10.1111/j.1945-1474.2012.00209.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Slaghuis SS, Strating MMH, Bal RA, et al. A framework and a measurement instrument for sustainability of work practices in long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:314. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zakumumpa H, Bennett S, Ssengooba F. Accounting for variations in art program sustainability outcomes in health facilities in Uganda: a comparative case study analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:584. 10.1186/s12913-016-1833-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodman RM, McLeroy KR, Steckler AB, et al. Development of level of institutionalization scales for health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1993;20:2993:161–78. 10.1177/109019819302000208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Khanal S, Ibrahim MIBM, Shankar PR, et al. Evaluation of academic detailing programme on childhood diarrhoea management by primary healthcare providers in Banke district of Nepal. J Health Popul Nutr 2013;31:231–42. 10.3329/jhpn.v31i2.16388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lean M, Leavey G, Killaspy H, et al. Barriers to the sustainability of an intervention designed to improve patient engagement within NHS mental health rehabilitation units: a qualitative study nested within a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:209. 10.1186/s12888-015-0592-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Braithwaite J, Westbrook M, Nugus P, et al. A four-year, systems-wide intervention promoting interprofessional collaboration. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:99. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dixon-Woods M. How to improve healthcare improvement-an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods. BMJ 2019;367:l5514. 10.1136/bmj.l5514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health – translating science to practice. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Churruca K, Ludlow K, Taylor N, et al. The time has come: embedded implementation research for health care improvement. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25:373–80. 10.1111/jep.13100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Manyazewal T. Using the World Health Organization health system building blocks through survey of healthcare professionals to determine the performance of public healthcare facilities. Arch Public Health 2017;75:50–7. 10.1186/s13690-017-0221-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pencheon D. Developing a sustainable health care system: the United Kingdom experience. Med J Aust 2018;208:284–5. 10.5694/mja17.01134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tran BX, Nghiem S, Sahin O, et al. Modeling research topics for artificial intelligence applications in medicine: latent Dirichlet allocation application study. J Med Internet Res 2019;21:e15511. 10.2196/15511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tran BX, Vu GT, Ha GH, et al. Global evolution of research in artificial intelligence in health and medicine: a bibliometric study. J Clin Med 2019;8:E360. 10.3390/jcm8030360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pluye P, Potvin L, Denis J-L. Making public health programs last: conceptualizing sustainability. Eval Program Plann 2004;27:121–33. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2004.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buchanan D, Fitzgerald L, Ketley D, et al. No going back: a review of the literature on sustaining organizational change. Int J Management Reviews 2005;7:189–205. 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00111.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Proctor E, Luke D, Calhoun A, et al. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement Sci 2015;10:88. 10.1186/s13012-015-0274-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-036453supp001.pdf (126.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-036453supp002.pdf (82.3KB, pdf)