Abstract

Introduction

Case management (CM) in a primary care setting is a promising approach to integrating and improving healthcare services and outcomes for patients with chronic conditions and complex care needs who frequently use healthcare services. Despite evidence supporting CM and interest in implementing it in Canada, little is known about how to do this. This research aims to identify the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a CM intervention in different primary care contexts (objective 1) and to explain the influence of the clinical context on the degree of implementation (objective 2) and on the outcomes of the intervention (objective 3).

Methods and analysis

A multiple-case embedded mixed-methods study will be conducted on CM implemented in ten primary care clinics across five Canadian provinces. Each clinic will represent a subunit of analysis, detailed through a case history. Cases will be compared and contrasted using multiple analytical approaches. Qualitative data (objectives 1 and 2) from individual semistructured interviews (n=130), focus group discussions (n=20) and participant observation of each clinic (36 hours) will be compared and integrated with quantitative (objective 3) clinical data on services use (n=300) and patient questionnaires (n=300). An evaluation of intervention fidelity will be integrated into the data analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

This project received approval from the CIUSSS de l'Estrie – CHUS Research Ethic Board (project number MP-31-2019-2830). Results will provide the opportunity to refine the CM intervention and to facilitate effective evaluation, replication and scale-up. This research provides knowledge on how to resp ond to the needs of individuals with chronic conditions and complex care needs in a cost-effective way that improves patient-reported outcomes and healthcare use, while ensuring care team well-being. Dissemination of results is planned and executed based on the needs of various stakeholders involved in the research.

Keywords: primary care, qualitative research, organisation of health services, protocols and guidelines

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This protocol details the steps for the implementation of a case management (CM) intervention for frequent users of health services with chronic conditions and complex care needs.

A novel conceptual model for CM implementation is proposed based on the integrative functions of primary care and the effective implementation of healthcare interventions.

The barriers and facilitators to implementing CM will be detailed and the influence of the clinical context on the degree of implementation and on the outcomes of the intervention will be evaluated.

While the proposed conceptual model does not cover every possible construct for effective implementation, an inductive approach to data analysis will be used to allow for emergent themes and all stakeholders will participate in data analysis in order to ensure validity.

Introduction

A priority for primary care research and the Canadian healthcare system is to address the complex needs of patients who frequently use healthcare services.1 2 These patients may suffer from a combination of chronic illnesses, mental illness and/or socioeconomic vulnerabilities.3–5 Patients with chronic illnesses typically have a wide range of needs that require them to adopt new behaviours, such as meeting with care providers on a regular basis, adhering to treatment plans, monitoring their symptoms and making important decisions while also changing aspects of their lifestyle to preserve their physical, psychological and social well-being.6–8 Far from ‘misusing’ the healthcare system, studies show that frequent users do so in an attempt to address unmet needs for healthcare and social services.3 9 Studies suggest that these attempts are often unsuccessful and result in repetitive use of services in an uncoordinated way through frequent hospitalisations or visits to the emergency department.10 11 This leads to negative experiences for both the care providers and for the patients, poor health indicators and high mortality rates for the patients and considerable costs to the healthcare system.11–13 Several countries have, therefore, experimented with new models of healthcare delivery that can achieve better coordination and integration of services, some of which have been found to reduce fragmentation and improve care continuity.14 Early examples of such models include the chronic care model (CCM)15 and the innovative care for chronic conditions framework.16 These models emphasise the importance of providing support to patients for self-management and decision making, seeking innovative approaches within available clinical information systems and proposing ways to redesign the delivery of healthcare.14

Individuals with chronic illnesses require organised care and close follow-up delivered over an extended period of time.17 The primary care setting is the most suitable for supporting individuals with chronic illnesses due to its defining features of patient-centred first contact, continuous, comprehensive and coordinated care.17 18 Health systems built on the principles of primary care achieve better health outcomes and greater equity, at a lower cost19 than systems with a specialty care orientation.18 Integrated care may be achieved in a primary care setting through the creation of intersectorial linkages between health and social policies, that is, the linking of healthcare to other human service systems (eg, long-term care, education, vocational and housing services) in order to improve clinical outcomes, patient and provider satisfaction and efficiency.14 18 20

Case management

Case management (CM) in a primary care setting is one approach that has been shown to increase the integration of health services21 22 and to improve care and outcomes for patients with chronic conditions and complex needs who frequently use healthcare services.23 24 Defined as ‘a collaborative, client-driven process for the provision of quality health and support services through the effective and efficient use of resources’,25 CM is among the best models available to mitigate the high utilisation of the healthcare system and associated costs.23 26 An adaptive randomised trial of CM interventions targeting frequent users of health services demonstrated that appropriate patient identification, staff training and centralised intervention delivery are components of CM that can be successfully implemented on a large scale and lead to a decrease in health consumption.27 A recent systematic review10 identified the most common components of CM interventions for chronically ill patients including the integration of services between hospitals and home or other facilities, regular home visits, regular telephone calls, individual assessment and care planning, education and self-management support, psychosocial support, and ongoing supervision and assessment. The same study found that a reduction in hospital admission rates was reported after implementation of CM interventions.10 A systematic review of literature on the characteristics of CM interventions in primary care reporting positive outcomes for frequent users of healthcare revealed three essential requisites for success. First, the intervention must identify and target patients with the greatest needs, and who are therefore most likely to benefit from the intervention. Second, the intervention must be delivered with sufficient intensity (ie, frequently enough or with a high enough dose) to produce the desired effect. Third, an interdisciplinary approach to care planning is preferred, where a variety of professionals from both care and cure sectors actively participate in the intervention.28

Despite the evidence base supporting CM as an intervention for frequent users, little evidence exists about the facilitators and barriers to CM implementation.29 Although there is a strong interest in implementing CM in the Canadian primary care setting, little information is available on how to do this. CM has rarely been implemented and documented systematically in order to identify and replicate best practices. This protocol is part of a larger research programme on CM in primary care for frequent users of healthcare services with chronic diseases and complex care needs2 and details the steps for the implementation analysis that was not described in the original protocol of the whole programme.

Objectives

To identify the barriers and the facilitators to implementation of the CM intervention in different primary care contexts.

To explain the influence of the clinical context on the degree of implementation.

To evaluate the influence of the context of implementation on the outcomes of the intervention.

Methods/design

Conceptual model

The conceptual model developed to guide this research protocol was informed by two multilevel conceptual frameworks in order to analyse the effective implementation of an integrative primary care intervention. Multilevel frameworks represent the interacting layers of phenomena inherent to organisations and are commonly used to develop theories, measure and analyse phenomena while accounting for the complexity inherent to these systems.30 31 Multilevel interventions mobilise resources and facilitate linkages across organisations ‘to solve coordination problems and adapt to change’.31

The first framework used to guide this research protocol is the Valentijn et al framework for integrated care based on the integrative functions of primary care.18 The concept of integration originates from organisational theory and refers to ‘the quality of the state of collaboration’ that may exist among the multiple levels of service delivery with the purpose of achieving a required mutual effort and agreement.14 Integrated healthcare interventions are a means to improve access, quality and continuity of services in a more efficient way, especially for people with complex needs.18 This framework describes the central role of primary care in integrating the multiple levels of healthcare: system integration at the macrolevel; organisational and professional integration at the mesolevel; clinical integration at the microlevel; and functional and normative integration to link the macro, meso and microlevels.18 Valentijn et al’s framework is intended for analysing and testing the causal relationships within and between the integration levels, which interact to varying degrees depending on the specific context of healthcare delivery.18 This framework is therefore suitable for studying the different primary care contexts of the CM intervention from the perspective of integrated care and is the unifying thread to the implementation and evaluation of the CM intervention.

The second framework used to guide this research protocol is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), intended to promote effective implementation and formative evaluation of complex, multilevel interventions in healthcare.32 The CFIR provides a taxonomy of constructs that can be used to understand, measure and assess implementation across a variety of contexts. The constructs are categorised into five major domains that similar to the Valentijn et al18 framework, reflect a multilevel perspective. The outer setting refers to the economic, political and social context in which the implementing organisation is situated and corresponds to the macrolevel. The inner setting corresponds to the mesolevel of the organisational context and includes constructs such as the structure and culture of the implementing organisation. At the microlevel, the individuals involved in the intervention are described. The CFIR includes two additional domains: the characteristics of the intervention, a description of its core components and the implementation process, considered a dynamic, non-sequential and non-linear domain that can stem from any level, macro, meso or micro.32 When understood, process provides insight that links the various levels of analysis and shed light on the causal or generative mechanisms underlying the intervention being studied.32 33 Barriers and facilitators may arise at multiple levels of intervention delivery, as external influencers, organisational or professional components or during the process by which an intervention is adopted within an organisation.32

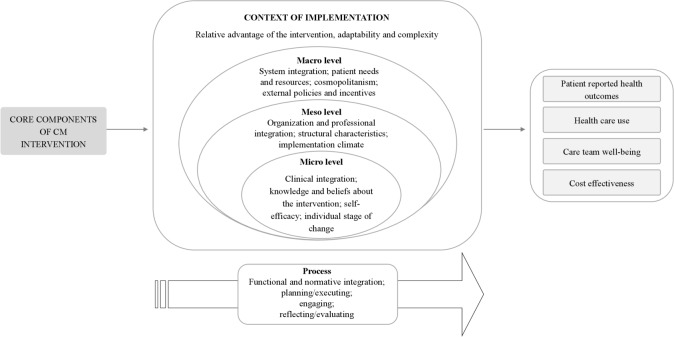

The conceptual model developed to guide this research protocol is presented in figure 1. On the left side of the figure are the core components of the CM intervention, described in the proceeding section. During implementation, the intervention takes on unique properties and characteristics related to the local context in which it is introduced (referred to in figure 1 as the context of implementation).32 The context of implementation includes macro, meso and microlevel determinants, depicted by the concentric circles in the middle of the figure. The process of implementation is represented by the arrow at the bottom of the figure, which represents the dynamic and continuous nature of intervention implementation. Finally, to the right, are the final expected outcomes of the intervention, based on the quadruple aims to optimise health system performance: improved patient outcomes, healthcare use, care team well-being and cost-effectiveness.34

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for the implementation analysis of a case management (CM) intervention.

Constructs were selected from both Valentijn et al18 and Damschroder et al32 to reflect the objectives of this research. The characteristics of the intervention after implementation in a particular local context will be analysed based on the intervention’s adaptability to meet local needs, its relative advantage to the context, and its complexity or difficulty of implementation. At the macrolevel, how the intervention contributes to system integration will be examined, including vertical integration and collaboration across care sectors and horizontal integration through a holistic view of the patient.18 This construct reflects the implementing organisation’s knowledge of the needs of its patient population and its ability to respond with appropriate structures, techniques and resources (patient needs and resources).32 The organisation’s degree of networking with external services and structures (cosmopolitanism) will be examined, as well as its formal strategies and policies supporting external linkages (external policies and incentives).

At the mesolevel, organisational and professional integration will be examined, which refer to the partnerships between services and professionals within the implementing organisation. The structural characteristics of the organisation and the implementation climate will be described. At the microlevel, interest will shift to clinical integration, which reflects the level of coordination and coherence of the primary care delivery process.18 The knowledge and beliefs of the various professionals involved in the intervention will be examined, as well as their perceived self-efficacy to implement CM, and their individual stage of change, which refers to their progress towards full adoption and sustained use of the intervention.32

Finally, the process of implementation will be analysed by examining how the CM intervention was planned and executed at the local level, how professionals were mobilised and engaged for participation in the intervention, and by examining the mechanisms put in place to discuss and provide feedback about the experience, progress and quality of implementation (planning/executing; engaging; reflecting/evaluating). These constructs reflect the level of functional and normative integration resulting from the implementation of the intervention: how the implementing organisation mobilised management functions in support of the intervention, as well as the degree of development of a shared goal or mission among participating individuals and partner organisations for the implementation of the intervention.18

The intervention

An intervention was designed to reflect the standards of practice of the National Case Management of Canada as well as the Case management society of America.25 35 The activities of the intervention follow the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Strategy for Patient-Oriented research and incorporate the integration characteristics of the National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support.36 37 Patients with chronic conditions most often seek and receive comprehensive care in a primary care setting38 and the leadership of a case manager who is experienced in primary care has been shown to facilitate the successful implementation of CCMs.39 The CM intervention is therefore designed to be delivered by a primary care health professional in a primary care clinical setting over a period of 12 months.

In consideration of these guidelines and of the results of previously cited studies,10 11 23 27 28 an intervention was designed comprised four main components: (1) evaluation of patient needs and preferences; (2) codevelopment and maintenance of a patient-centred individualised services plan (ISP); (3) coordination of services among all partners and (4) education and self-management support for patients and families.

Evaluation of patient needs and preferences

The identification of patients who are in need of intervention and who stand to benefit the most from CM is an essential first step,27 28 ideally executed by an interdisciplinary team.5 40 Patients are identified by searching administrative data or clinical records in addition to their referral for the CM intervention by primary care professionals. This approach combines clinician judgement with objective data from electronic medical record or administrative databases.2 41 The CM intervention targets patients who present with at least one chronic illness, including mental illness, who frequently use health services as determined by four or more emergency department visits or hospitalisations in the previous 12 months, and who have complex needs as determined by the care team. Once a patient has been identified for inclusion in the CM intervention, the case manager examines the patient’s medical records going back 12 months in order to understand the reasons for the frequent use of services. The case manager identifies the patient’s physical and/or mental illnesses as well as social challenges such as insecure housing or employment, poverty, violence, substance use disorders, etc. The case manager also documents the health and social services previously provided to the patient, as well as the names, roles and contact information of professionals currently involved with the patient or who may eventually be called on to participate in the care of the patient.

The case manager validates with the patient the information collected from the medical records and determines the patient’s personal needs and preferences for future services and resources. This step constitutes the first in-depth interaction between the case manager and the patient, and is essential for building mutual trust and respect,21 for establishing a patient-centred care process, and for encouraging the commitment of the patient as a partner in the care process.42 43 The patient may prefer to be accompanied by a caregiver or advocate with lived experience of the patient’s health situation who can assist in navigating the health and social services system.44 When referring to ‘the patient’ in this article, we also refer to an individual who may stand in for the patient at any point during the intervention. Finally, the case manager seeks the patient’s consent to communicate with potential care professionals throughout the intervention and ensures that the patient understands and agrees to the next step of the intervention: the creation of an ISP. The ISP is a tool for planning and coordinating tailored services intended to give meaning and direction to the patient in consideration of his or her life goals,45 personal environment, resources and culture, in collaboration with a multidisciplinary team of professionals46 and health and social services organisations.

Codevelopment and maintenance of a patient-centred ISP

The ISP for patients with chronic conditions may lead to improvements in physical and psychological health, as well as in their ability to self-manage their condition.46–48 It is among the most commonly used strategies in CM interventions.10 11 The case manager identifies resources available in the local health and social services network and within the community that may be appropriate for the patient. This involves a holistic analysis of the patient’s situation and the identification of clinical administrative issues and a final list of care professionals that will be invited to examine the patient’s situation. These may be healthcare and social services professionals, managers or representatives of community organisations. The case manager communicates directly with targeted care professionals to request their involvement, to ensure that the reason for the intervention is understood and to agree on a mutually convenient date, time and place for an ISP meeting with the patient. The case manager prepares the agenda for the ISP meeting and communicates with the patient to reconfirm consent regarding the professionals who will participate in the meeting and to maintain a relationship of trust and transparency with the patient. The ISP meeting is ideally held in-person, but may be done by phone or online.

At the beginning of the ISP meeting, the care team reviews the potential resources and services that may be proposed to the patient prior to the patient’s arrival. This allows the care team to collaboratively examine the patient’s situation, needs and preferences and to mobilise their multidisciplinary perspectives.46 The ISP is then developed with the patient and their advocate on their arrival. The ISP includes a maximum of three or four objectives in line with the patient’s overall expectations and life project.49 The group proposes preferred methods of communication and strategies for exchanging information for the duration of the intervention. The case manager writes up the ISP in plain language and validates that the patient understands and agrees to it.

Coordination of services among all partners

Patients with chronic illnesses and complex care needs are often cared for by multiple providers in various locations and experience difficulty navigating the health system and other ressources resulting in unmet needs, a lower quality of life and higher mortality rates.48 A coordinated response by care providers that promotes patient empowerment over an extended period of time is recommended.14 In this intervention, the case manager transmits a copy of the written ISP to the patient and the care team and follows up regularly with the patient’s primary care providers in the clinical setting, ensuring active engagement and direct communication. As the principal contact person and advocate for the patient, the case manager establishes contact with the services or resources identified in the ISP, providing a personalised reference for the patient, explaining the case and informing care professionals of past and potential challenges facing the patient.

Regular communication and follow-up encourages the patient’s active engagement in the intervention, a strategy that has been shown to reduce future use of emergency services.26 50 51 The case manager talks to the patient about their preferred method for reaching the case manager and other relevant services. Adherence to the ISP throughout the intervention is ensured by maintaining contact with the care professionals involved with each patient, and by verifying if the patient’s goals have been attained. The ISP should be reviewed at least once every 3 months. If the patient desires a change in their ISP, or if a care professional identifies any issues throughout the intervention, the case manager reassesses the situation with the patient and adjusts the ISP as necessary.

Education and self-management support for patients and families

Self-management support was found to be the strategy most frequently associated with health improvements in patients with chronic diseases in a primary care setting.17 Education and self-management support activities aim to increase the patient’s skills, confidence and motivation to control and manage their symptoms and to follow their ISP with structured support for problem solving and continuous assessment of the patient’s objectives and progress.52 This component of the intervention is considered an ongoing and transversal process to be performed as needed throughout the intervention.

Case managers aim to develop the patient’s ability to monitor their condition, take appropriate action and identify when and how to ask for professional help by assessing the patient’s knowledge and learning needs and suggesting beneficial activities, such as journaling symptoms and vitals, and informational resources based on the patient’s unique situation. Case managers are trained in motivational interviewing, a ‘client-centred, directive communication method aimed at changing behaviour’.53 The case manager supports the patient to set realistic goals through a ‘smart’ action plan that includes specific behavioural goals that are measurable and attractive to the patient, which may be accomplished in a realistic time frame and that build on previous positive experiences. The case manager helps the patient prepare for meetings with the various care professionals to ensure that the patient is empowered to communicate his or her goals and to receive the desired care. Patients are coached on how to effectively communicate with their relatives, to establish expectations and to ensure a successful care partnership.

Study setting

The CM intervention will be implemented in 10 primary care clinics, each representing a unique case. Two clinics were selected from each of the five participating Canadian provinces of Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Québec and Saskatchewan using a purposeful sampling strategy.54 Clinics were selected that had not previously implemented CM and that were interested in implementing the CM intervention and participating in the research project. The interest of a healthcare professional, a nurse or a social worker, to develop the role of the case manager and to be available to dedicate approximately 1 day per week to the study was essential. The case manager was required to have primary care experience and was offered training in the intervention and continuous support and follow-up through the establishment of a community of practice.

Patient and public involvement

Patient partners were involved in this research since its inception, including the design of the research questions and the development of this protocol of which they are coauthors (VS and MW). They continue to provide their expertise regarding study feasibility and acceptability. They will be involved in the interpretation of data and in the dissemination of results.

Timeline

The implementation of the CM intervention will take place over a period of 1 year. A cohort of patients will be recruited at each clinic and will be administered the intervention over the course of 12 months.

Patient recruitment

Each clinic will identify 30 patients for enrolment in the CM intervention, for a total of 300 patients across the five participating provinces. Patients are selected who are most likely to benefit from CM, based on the clinical judgement of the case manager and the family physician. Criteria for inclusion in the study are as follows: (1) living with at least one chronic physical or mental illness; (2) frequent user of healthcare services that is, having four or more hospitalisations or visits to the emergency department in the previous year; (3) having complex care needs as determined by the care team. Patients who are ineligible for participation in the study include individuals whose prognosis is less than 1 year or who are exhibiting a loss of autonomy.

Study design

The implementation analysis is designed as a multiple-case embedded study, where each of the ten clinics will represent one subunit of analysis. This design is best suited to analysing complex interventions implemented in variable and dynamic settings, and where the underlying context is difficult to isolate from the intervention itself.55 This design allows several levels of analysis, the observation of various organisational processes or behaviours, the examination of the context and process of implementation, and the interaction among involved stakeholders.56 It also favours the use of mixed methods of data collection and analysis.57

Data collection

To accomplish the objectives of this research, a mixed-methods data collection is planned. Multiple sources of information will be used to collect both qualitative and quantitative data.

Individual semistructured interviews will be administered to all case managers (1–2 per clinic) and clinic managers (one per clinic) at each study site at the start of the intervention (T0), and at the end of the intervention (T12 months). At the end of the intervention (T12 months), 10 patients and/or their representative will also be interviewed. Patients will be purposefully selected to achieve maximum variation.54 A total of 130 individual semistructured interviews will be administered across the 10 participating clinical sites. An interview guide was developed composed of 18 open-ended questions based on the constructs of the conceptual model (figure 1). The first part of the interview will address the clinical context of the CM intervention, the services offered at each clinical site to patients with chronic conditions and complex care needs, and the way in which the clinic works with other health and social services organisations. In the second part of the interview, questions will be asked about the implementation of the four components CM intervention, the context of implementation, the barriers and facilitators to intervention and about individual perceptions and attitudes towards the intervention.

Focus groups

A focus group discussion will be held at each participating clinic, once at the beginning of the intervention (T0) and once at T9-12 months, for a total of 20 focus groups throughout the CM intervention. Primary care providers including physicians, nurses, social workers, pharmacists and any health and social services professionals involved in the intervention will be invited to take part in a discussion facilitated by a member of the PriCare research team. The interview guide described above for the semistructured interviews will be adapted and used to guide the focus group discussion.

Non-participant observation

The activities of the intervention at each of the 10 clinical sites will be observed for 36 hours during the implementation year. A member of the PriCare research team will observe the CM activities including the meetings between the patient and the case manager, the development of the ISP, meetings between the primary care professionals, and any other activities adopted by the clinic under observation. Data collection will be guided by means of an observation grid developed to reflect the four components of the CM intervention and the constructs of the conceptual framework.

Clinical data on services use

Quantitative data from patient medical records will be collected at the beginning (T0) of the intervention for a period of 12 months, before the patient’s first visit with the case manager, and at the end of the intervention 12 months) (n=300). The purpose of this data collection is to compare the utilisation of services in the year before the intervention with utilisation during the intervention. Data will include the number of emergency department visits, overnight stays in the hospital and primary care professional visits. Patient expenditures from these activities will be calculated using an established fee schedule from the Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) patient cost estimator.58 The cost of the intervention will be measured by tracking expenditures related to the CM activities.

Patient self-administered questionnaires

Participating patients (n=300) will be asked to complete a 30 min questionnaire at baseline (T0), at the halfway point (T6 months) and at the end of the intervention (T12 months) under the guidance of a member of the PriCare research team. Questionnaires are available in both English and French and have been validated. Data collected will include age, gender, marital status, education, occupation, economic status with family income and patient perception of his or her economic situation, health literacy, multimorbidity, care integration, self-management and quality of life. Health literacy will be measured using Chew’s three questions for screening patients with inadequate or marginal health literacy,59 60 multimorbidity with the Disease Burden Morbidity Assessment (21 items),61 62 care integration with the Picker Institute Questionnaire (13 items),63 self-management with the Partners in Health Scale (12 items),64 65 quality of life with the short form survey, version 2 (SF-12 V.2) (12 items),66 quality-adjusted life years (QALY) derived from the SF-12 V.267 and psychological distress with Kessler’s six questions regarding a person’s emotional state.68

Intervention fidelity evaluation

The degree to which an intervention is delivered as intended is critical to the attainment of expected outcomes.69 70 Referred to as intervention fidelity, the delivery and the degree of adherence to the four main components of the intervention will be assessed based on the qualitative and quantitative data collected by a member of the PriCare research team during the intervention year. A fidelity grid was developed using the Carroll et al71 conceptual framework for implementation fidelity.71 In addition to identifying the essential components of the intervention as described previously, adherence to the content, frequency, duration and coverage of the intervention as described in this protocol, as well as the moderating factors that may influence implementation such as intervention complexity, the facilitation strategies used, the quality of intervention delivery, and the responsiveness of participants will be documented.71 The fidelity grid guides the data collection via a series of general questions referring to each element of71 conceptual framework, identifies primary and secondary sources of data and specifies the data collection method for each element of the conceptual framework.

Outcome variables

As described in the conceptual model (figure 1), the main outcomes of the intervention that will be examined are based on the quadruple aims to optimise health system performance: improved patient-reported outcomes, healthcare use, cost-effectiveness and care team well-being.34 Self-management and quality of life are the main patient-reported outcomes collected from the patient-administered questionnaire at baseline and at the end of the intervention (T12 months). Healthcare use will be based on the clinical data collected on services use including the number of emergency department visits, overnight hospital stays and primary care professional visits. It will also be based on health services integration, assessed within the patient-administered questionnaire. Care team well-being will be evaluated from the data collected from the individual semistructured interviews and focus group discussions with healthcare professionals. Finally, cost-effectiveness will be based on the CIHI cost estimator, as previously described.

Analysis

A combination of analytical strategies will be used to reflect the variability and dynamic nature of context analysis and the mixed methods approach as used in this research.55 57 72 First, qualitative and quantitative data collected will be integrated through a comparison of results for similarities and differences throughout the analysis phase.72 Second, qualitative and quantitative data will be compared for variables measured in several ways such as health services utilisation, self-management, quality of life and care integration.73 Third, qualitative and quantitative data will be merged for each of the 10 cases (the participating clinical sites). A case history will be reported for each clinical site that will constitute the synthesis of the merged data. Fourth, a comparison of the cases will be completed using a mixed methods matrix.54 All categories of stakeholders involved in this research including the principal investigators, research assistants, patient partners, clinical experts, technical and scientific experts and policy-makers, will be called on to participate in the data analysis to ensure valid and meaningful interpretations. Additional analytical techniques for case study research55 will be used as detailed below.

Objective 1

To identify the barriers and the facilitators to implementation of the CM intervention in different primary care contexts, the qualitative data collected using individual semistructured interviews, focus groups and non-participant observation will be analysed. Responses to questions regarding the perceived barriers and facilitators to responding to the needs of patients with chronic conditions and complex care needs, to working with internal clinic partners and external health and social services partners to care for this patient population, and to the process of implementing the four main components of the CM intervention will be extracted and analysed. Information regarding the perceived complexity of the intervention, ease of implementation, care professional engagement and satisfaction with the intervention and available support strategies to facilitate implementation will be extracted from the data collection grid used for the non-participant observation and for the fidelity evaluation.

Objective 2

A similar approach will be taken to explain the influence of the context of implementation on the degree of implementation. Interviewees and participants in the focus group discussions will be asked specific questions regarding the local clinical context, the workplace environment, relationships with external health and social services partners, individual attitudes and perceptions to the intervention and the overall process of implementation of the CM intervention. This information will be extracted and compared with the results of the fidelity evaluation to assess the degree of implementation of the intervention.

A mixed thematic analysis approach will be used.54 Each of the 10 clinical sites will be analysed separately as an individual case study using a deductive approach based on the conceptual model (figure 1), as well as an inductive approach based on emergent constructs. A case history will be reported, guided by the constructs of the conceptual model (figure 1). Subsequent to individual analysis of the 10 cases, a comparison between the cases will be performed using a descriptive and interpretative matrix.54 This approach allows systematic comparison among cases and among units of analysis. Analytical techniques specific to case study research will be used as described in55 including pattern comparison, research of competing explanations and construction of explanations. Qualitative data will be managed using multisite NVivo V.12 server software (QSR International).

Objective 3

To evaluate the influence of the context of implementation on the outcomes of the intervention, clinical data on services use and quantitative data extracted from the patient self-administered questionnaires will be analysed using descriptive statistics. Quantitative data will be analysed first and then interpreted in integration with qualitative data and the intervention fidelity evaluation described above, rather than trying to calculate non-biased quantitative effects.73 Regression models will be developed to evaluate the relationships between intervention fidelity, patient characteristics, the constructs of the conceptual model reflecting the contextual elements of the intervention and the outcomes of the intervention. This will be done using SPSS V.26. An incremental cost-effectiveness/utility ratio74 will be calculated using data collected on costs and QALY before and after implementation of the CM intervention. Multivariate parametric analyses with bootstrap replications will be conducted together with cost-effectiveness acceptability curves.75

Discussion

CM is a promising approach to delivering care to patients with chronic illnesses and complex care needs, but little is known about its implementation in a primary care setting.21 As an intervention composed of multiple components and steps that will be implemented in multiple sites, CM is an example of a complex, context-dependent intervention.76 Identifying and analysing the contextual determinants across a variety of sites is necessary to understand how the intervention can produce its intended outcomes.77 An implementation analysis achieves a deeper understanding of the conditions that are most likely to lead to the successful implementation of the core components of the intervention.56 It serves to identify variation in outcomes associated with different contexts and to identify implementation problems.73 An implementation analysis can reveal how an intervention causes change in a particular context and highlights an intervention’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to intended outcomes.56

This research will detail the steps involved in implementing the four main components of the CM intervention at different clinical sites and will identify barriers and facilitators to implementation, providing the opportunity to address potential problems and to refine the intervention. This context of implementation which will be further understood through a detailed, theoretically based approach to the identification and analysis of the macro, meso and microlevel determinants of implementation.18 32 The implementation process will be studied, highlighting the development and change across time of the steps required to implement the intervention in various contexts. This research will respond to some of the most important issues raised in recent publications on CM for frequent users of healthcare services with chronic illnesses and complex care needs,21 23 24 26 by contributing to the understanding of how to implement this intervention in different primary care contexts in a cost-effective way that improves patient reported outcomes and healthcare use, while ensuring the well-being of the care team.

The multilevel conceptual framework proposed in this study may be helpful for future research because it combines the approach to analysing the effective implementation of healthcare interventions, with the principles of the integrative functions of primary care. The resulting framework supports the analysis of effective implementation not only of CM, but also of primary care interventions aiming to achieve care integration. The framework reflects the importance of intersectorial linkages and ensures the incorporation of constructs aimed to improve access, quality and continuity of services for patients with complex needs,18 regardless of the intervention being implemented. It is also particularly suited to the analysis and formative evaluation of complex, multilevel interventions in healthcare, verifying what works where and why across multiple contexts.32 The conceptual framework represents how patient, organisational and systems-level elements of implementation, the dynamic, time-dependent process of implementation, and the defining features of primary care, can translate into meaningful intervention outcomes, based on the quadruple aims to optimise health system performance. The framework can inform the effective implementation of complex primary care interventions that seek to facilitate the continuous, comprehensive and coordinated delivery of services to individuals or populations, and that necessitate the engagement of multiple stakeholders across various sectors.

The use of ‘multistrategy’ or ‘multifaceted’ frameworks to describe and analyse the implementation of complex interventions increases the precision and specificity of reporting, which facilitates effective evaluation and replication.78 79 The proposed research fulfils an essential step towards replication and scalability of CM by identifying the implementation strategies that support the adoption, scale-up and replication of best practices in CM.78 80 Given the complex nature of the CM intervention, practitioners report challenges to implementation, especially considering the lack of guidelines or a blueprint on how to operationalise its core components across different settings.81 Implementation is often poorly reported in published literature, which presents a challenge to both research and practice and impedes replication and immediate adoption in a clinical setting.79 82 To achieve wide-scale adoption and replication, the CM intervention must be tailored to the local context in an approach that considers the individual, the team of professionals, the organisational setting and the greater system.81 Few studies have described, categorised and analysed intervention implementation in a contextually tailored approach.82 This research will thus provide this information for both researchers and practitioners, which according to our knowledge, has not yet been done.

Study validity

Construct validity is ensured through a detailed conceptual model and consistency in the application of its constructs in the data collection and analysis. Internal validity is ensured through a systematic coding and rigorous organisation of collected data and the triangulation of several sources of qualitative data acquired from different participating stakeholders including patients, case managers, clinic managers, researchers, clinicians and informal caregivers.55 Analysis and comparison of different case studies in various implementation contexts will reinforce external validity and transferability. The observation and analysis of multiple levels, and their replication across several cases enhances both internal and external validity.55

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the PriCare research group and collaborators for their coordination and methodological support: PL Bush, Y Couturier, L Guénette, A Luke, P Morin, P Pluye, TG Poder, ME Poitras, P Roberge, R Valaitis, V, C Longjohn, C Spence, J Porter, D Rubenstein, R Stoddard, S Bighead, C Campbell, L Edwards, P Gauthier, R Gibson, J Labbé, F Dubé, DA Roy, T Sampalli, J Young, M Brodeur, B Davis, S Gander, J Godbout, N Rabbitskin, J Splane, F Lemire, A Rondeau, N Senn, E Shadmi and the PriCare research team.

Footnotes

Twitter: @MaudCChouinard

Contributors: AD: conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting and substantial revisions to the manuscript; M-CC: conception of work; analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; KA-B: conception of work; analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; FB: conception of work; analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; SD: conception of work; analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; VRR: conception of work; analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; MB: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; MC: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; BC: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; ML: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; CP: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; VS: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; MW: analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revision to the manuscript; CH: conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; substantial revisions to the manuscript; guarantor of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript and agree to be responsible for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This work is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) – Operating Grant: SPOR PIHCI Network: Programmatic Grants (grant number 397896) and other partners such as Axe santé-Population, organisations et pratiques du CRCHUS, Centre de recherche du CHUS, Département de médecine de famille et médecine d’urgence (Université de Sherbrooke), Fondation de l’Université de Sherbrooke, Fondation de Ma Vie, Fonds de recherche du Québec en santé, Institut universitaire de première ligne en santé et services sociaux, Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec, New Brunswick Health Research Foundation, Nova Scotia Health Authority, Faculty of Medicine of Dalhousie University and Dalhousie Medical Research Foundation, Réseau-1 Québec, Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation and Université de Sherbrooke and Université du Québec à Chicoutimi.

Disclaimer: Patients and family partners, clinicians, policy-makers and researchers have formed a steering committee to collaborate in planning and executing this research process. A knowledge translation plan has been developed with the goals of increasing awareness and bringing change to practice, policy and future research. Dissemination goals are determined by each stakeholder group and executed by a group representative. Dissemination methods include news releases in social media and local/provincial media outlets, executive-summary reports to clinician audiences, presentations at meetings of Canadian professional associations (for family physicians, nurses and social workers), conference presentations at annual international meetings of the NAPCRG and the CAHSPR, and articles in peer-reviewed journals.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This project received approval from the CIUSSS de l'Estrie – CHUS Research Ethic Board (project number MP-31-2019-2830).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

References

- 1.Chouinard M-C, Hudon C, Dubois M-F, et al. . Case management and self-management support for frequent users with chronic disease in primary care: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:49. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Aubrey-Bassler K, et al. . Case management in primary care for frequent users of healthcare services with chronic diseases and complex care needs: an implementation and realist evaluation protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e026433. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, et al. . Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48:1–8. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee K-H, Davenport L. Can case management interventions reduce the number of emergency department visits by frequent users? Health Care Manag 2006;25:155–9. 10.1097/00126450-200604000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandelberg JH, Kuhn RE, Kohn MA. Epidemiologic analysis of an urban, public emergency department's frequent users. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:637–46. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb02037.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pope D, Fernandes CM, Bouthillette F, et al. . Frequent users of the emergency department: a program to improve care and reduce visits. CMAJ 2000;162:1017–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinius P, Johansson M, Fjellner A, et al. . A telephone-based case-management intervention reduces healthcare utilization for frequent emergency department visitors. Eur J Emerg Med 2013;20:327–34. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e328358bf5a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clarke LH, Bennett EV. Constructing the moral body: self-care among older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Health 2013;17:211–28. 10.1177/1363459312451181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rinke ML, Dietrich E, Kodeck T, et al. . Operation care: a pilot case management intervention for frequent emergency medical system users. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:352–7. 10.1016/j.ajem.2010.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joo JY, Liu MF. Case management effectiveness in reducing Hospital use: a systematic review. Int Nurs Rev 2017;64:296–308. 10.1111/inr.12335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soril LJJ, Leggett LE, Lorenzetti DL, et al. . Reducing frequent visits to the emergency department: a systematic review of interventions. PLoS One 2015;10:e0123660. 10.1371/journal.pone.0123660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moe J, Kirkland SW, Rawe E, et al. . Effectiveness of interventions to decrease emergency department visits by adult frequent users: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2017;24:40–52. 10.1111/acem.13060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shumway M, Boccellari A, O'Brien K, et al. . Cost-Effectiveness of clinical case management for ED frequent users: results of a randomized trial. Am J Emerg Med 2008;26:155–64. 10.1016/j.ajem.2007.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Series Caring for people with chronic conditions: a health system perspective. Berkshire, England: Open University Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner EH. Chronic disease management: what will it take to improve care for chronic illness? Eff Clin Pract 1998;1:2–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization Innovative care for chronic conditions: building blocks for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds R, Dennis S, Hasan I, et al. . A systematic review of chronic disease management interventions in primary care. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:11. 10.1186/s12875-017-0692-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, et al. . Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care 2013;13:e010. 10.5334/ijic.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips GA, Brophy DS, Weiland TJ, et al. . The effect of multidisciplinary case management on selected outcomes for frequent attenders at an emergency department. Med J Aust 2006;184:602–6. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q 1999;77:77–110. 10.1111/1468-0009.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Aubrey-Bassler K, et al. . Case management in primary care among frequent users of healthcare services with chronic conditions: protocol of a realist synthesis. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017701. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Diadiou F, et al. . Case management in primary care for frequent users of health care services with chronic diseases: a qualitative study of patient and family experience. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:523–8. 10.1370/afm.1867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Althaus F, Paroz S, Hugli O, et al. . Effectiveness of interventions targeting frequent users of emergency departments: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med 2011;58:41–52. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodenmann P, Velonaki V-S, Griffin JL, et al. . Case management may reduce emergency department frequent use in a universal health coverage system: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32:508–15. 10.1007/s11606-016-3789-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Case Management Network of Canada Connect, collaborate and communicate the power of case managment: Canadian standards of practice in case management. Canada: National Case Management Network, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar GS, Klein R. Effectiveness of case management strategies in reducing emergency department visits in frequent user patient populations: a systematic review. J Emerg Med 2013;44:717–29. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Edgren G, Anderson J, Dolk A, et al. . A case management intervention targeted to reduce healthcare consumption for frequent emergency department visitors: results from an adaptive randomized trial. Eur J Emerg Med 2016;23:344–50. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Pluye P, et al. . Characteristics of case management in primary care associated with positive outcomes for frequent users of health care: a systematic review. Ann Fam Med 2019;17:448–58. 10.1370/afm.2419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudon C, Chouinard M-C, Lambert M, et al. . Key factors of case management interventions for frequent users of healthcare services: a thematic analysis review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017762. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costa PL, Graça AM, Marques-Quinteiro P, et al. . Multilevel research in the field of organizational behavior. Sage Open 2013;3:215824401349824 10.1177/2158244013498244 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rousseau DM, Aguinis H, Boyd BK. Reinforcing the Micro/Macro bridge: organizational thinking and Pluralistic vehicles. J Manage 2011;37:429–42. 10.1177/0149206310372414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. . Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.SAGE Publications The SAGE Handbook of process organization studies. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2016. http://sk.sagepub.com/reference/the-sage-handbook-of-process-organization-studies [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med 2014;12:573–6. 10.1370/afm.1713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Case management society of America What is a case manager? 2019. Available: https://www.cmsa.org/who-we-are/what-is-a-case-manager/ [Accessed 12 Feb 2020].

- 36.Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for patient-oriented research, 2019. Available: https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html [Accessed 12 Feb 2020].

- 37.National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support Integrated care and support: our shared commitment. London: NHS, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grover CA, Crawford E, Close RJH. The efficacy of case management on emergency department frequent users: an eight-year observational study. J Emerg Med 2016;51:595–604. 10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Couturier Y, Gagnon D, Belzile L. La gestion de cas comme intermédiaire du “bien vieillir”. Entre autonomisation des usagers et protocolarisation des services aux personnes âgées en perte d’autonomie. Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques 2013;44:117–35. 10.4000/rsa.943 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borgès Da Silva R, Brault I, Pineault R, et al. . Nursing practice in primary care and patients' experience of care. J Prim Care Community Health 2018;9:215013191774718. 10.1177/2150131917747186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Freund T, Peters-Klimm F, Rochon J, et al. . Primary care practice-based care management for chronically ill patients (PraCMan): study protocol for a cluster randomized controlled trial [ISRCTN56104508]. Trials 2011;12:163. 10.1186/1745-6215-12-163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carreau E, Brière N, Houle N, et al. . Continuum of interprofessional collaborative practice in health and social care - Guide. Réseau de collaboration sur les pratiques interprofessionnelles en santé et services sociaux (RCPI), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grinberg C, Hawthorne M, LaNoue M, et al. . The core of care management: the role of authentic relationships in caring for patients with frequent hospitalizations. Popul Health Manag 2016;19:248–56. 10.1089/pop.2015.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manafo E, Petermann L, Mason-Lai P, et al. . Patient engagement in Canada: a scoping review of the 'how' and 'what' of patient engagement in health research. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:5. 10.1186/s12961-018-0282-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rijken M, Struckmann V, Heide vander, et al. . How to improve care for people with multimorbidity in Europe? Int J Integr Care 2016;16:A209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, et al. . Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:Cd010523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, et al. . Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA 2009;301:1771–8. 10.1001/jama.2009.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. . New 2011 survey of patients with complex care needs in eleven countries finds that care is often poorly coordinated. Health Aff 2011;30:2437–48. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rijken M, Van der Heide I, Heijmans M. Individual care plans in chronic illness care: aims, use and outcomes. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:209 10.5334/ijic.2757 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan BTB, Ovens HJ. Frequent users of emergency departments. do they also use family physicians' services? Can Fam Physician 2002;48:1654–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramos Salazar L. The effect of patient Self-Advocacy on patient satisfaction: exploring Self-Compassion as a mediator. Communication Studies 2018;69:567–82. 10.1080/10510974.2018.1462224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Health Council of Canada Self-Management support for Canadians with chronic health conditions. Canada: Health Council of Canada, 2012. https://www.selfmanagementbc.ca/uploads/HCC_SelfManagementReport_FA.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berthiaume P, Fortier D. [Motivational interview]. Perspect Infirm 2012;9:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE publications, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin RK. Case study research design and methods. 5th edn Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brousselle A, Champagne F, Contandriopoulos A, et al. . L’Évaluation: Concepts et Méthodes. Canada: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 57.SAGE Publications, Inc Embedded case study methods. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2002. https://methods.sagepub.com/book/embedded-case-study-methods [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canadian Institute for Health Information Patient cost estimator Canada: Canadian Institute for health information, 2019. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/patient-cost-estimator [Accessed 12 Feb 2020].

- 59.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med 2004;36:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hudon E, Hudon C, Couture EM, et al. . Measuring health literacy in primary health care: validation of a French-Language version of a Three-Item questionnaire. Colorado Springs, USA: North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poitras M-E, Fortin M, Hudon C, et al. . Validation of the disease burden morbidity assessment by self-report in a French-speaking population. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:35. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bayliss EA, Ellis JL, Steiner JF. Subjective assessments of comorbidity correlate with quality of life health outcomes: initial validation of a comorbidity assessment instrument. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2005;3:51. 10.1186/1477-7525-3-51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hudon E, Hudon C, Lambert M, et al. . Validation of a French-language version of a patient-reported measure of integrated care. Colorado Springs, USA: North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Smith D, Harvey P, Lawn S, et al. . Measuring chronic condition self-management in an Australian community: factor structure of the revised partners in health (PIH) scale. Qual Life Res 2017;26:149–59. 10.1007/s11136-016-1368-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hudon E, Hudon C, Lambert M, et al. . Measuring self-management of patients with chronic disease in primary care: validation of a French-language version of the partner in health scale. Colorado Springs, USA: North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ware J. User Manuel for the SF-36v2 health survey second edition. Quality Metric Incorporated: Lincoln, RI, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brazier JE, Roberts J. The estimation of a preference-based measure of health from the SF-12. Med Care 2004;42:851–9. 10.1097/01.mlr.0000135827.18610.0d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al. . K-6 Distress Scale - Self Administered, 2003. Available: http://www.midss.org/content/k-6-distress-scale-self-administered [Accessed 12 Feb 2020].

- 69.Haynes A, Brennan S, Redman S, et al. . Figuring out fidelity: a worked example of the methods used to identify, critique and revise the essential elements of a contextualised intervention in health policy agencies. Implement Sci 2016;11:23. 10.1186/s13012-016-0378-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Breitenstein SM, Gross D, Garvey CA, et al. . Implementation fidelity in community-based interventions. Res Nurs Health 2010;33:164–73. 10.1002/nur.20373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. . A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007;2:40. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pluye P, Bengoechea EG, Granikov V, et al. . A world of possibilities in mixed methods: review of the combinations of strategies used to integrate qualitative and quantitative phases, results and data. Int J Mult Res Approaches 2018;10:41–56. 10.29034/ijmra.v10n1a3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, et al. . Good research practices for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task force report. Value Health 2005;8:521–33. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00045.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fenwick E, O'Brien BJ, Briggs A. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves-facts, fallacies and frequently asked questions. Health Econ 2004;13:405–15. 10.1002/hec.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rogers PJ. Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation 2008;14:29–48. 10.1177/1356389007084674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rossi PH, Lipsey MW, Freeman HE. Expressing and Assessing Program Theory : Evaluation: a systematic approach. Thousand Oaks, CA, 2004: 152–78. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Huynh AK, Hamilton AB, Farmer MM, et al. . A pragmatic approach to guide implementation evaluation research: strategy mapping for complex interventions. Front Public Health 2018;6:134. 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci 2013;8:139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Castiglione SA, Ritchie JA. Moving into action: we know what practices we want to change, now what? an implementation guide for health care practitioners. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2012. https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/159 (cited 2020 February 12). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kadu MK, Stolee P. Facilitators and barriers of implementing the chronic care model in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:12. 10.1186/s12875-014-0219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Boyd MR, Powell BJ, Endicott D, et al. . A method for tracking implementation strategies: an exemplar implementing Measurement-Based care in community behavioral health clinics. Behav Ther 2018;49:525–37. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.