Abstract

Multiple studies show that racial and ethnic minorities with low socioeconomic status are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease–related dementias (AD/ADRD) in more advanced disease stages, receive fewer formal services, and have worse health outcomes. For primary care providers confronting this challenge, community-based organizations can be key partners in supporting earlier identification of AD/ADRD and earlier entry into treatment, especially for minority groups. The New York University Center for the Study of Asian American Health, set out to culturally adapt and translate The Kickstart-Assess-Evaluate-Refer (KAER) framework created by the Gerontological Society of America to support earlier detection of dementia in Asian American communities and assist in this community-clinical coordinated care. We found that CBOs play a vital role in dementia care, and are often the first point of contact for concerns around cognitive impairment in ethnically diverse communities. A major strength of these centers is that they provide culturally appropriate group education that focuses on whole group quality of life, rather than singling out any individual. They also offer holistic family-centered care and staff have a deep understanding of cultural and social issues that affect care, including family dynamics. For primary care providers confronting the challenge of delivering evidence-based dementia care in the context of the busy primary care settings, community-based organizations can be key partners in supporting earlier identification of AD/ADRD and earlier entry into treatment, especially for minority groups.

Keywords: dementia, geriatrics, underserved communities, community health, access to care, health promotion

A Growing Diverse and Aging Population

In 2014, 5 million Americans experienced Alzheimer’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease–related dementias (AD/ADRD); by 2060, this number is projected to swell to 13.9 million.1 Simultaneously, the share of adults 65 years and older who are non-Hispanic white is projected to drop from 77% to 55%, giving way to a substantially more diverse older population.2 Multiple studies show that racial and ethnic minorities with low socioeconomic status or education levels are not diagnosed with ADRD until in more advanced disease stages and receive fewer formal services resulting in worse health outcomes.3,4 As the population becomes more diverse, the National Institute on Aging5 and the US Department of Health and Human Services6 have called for strategies that focus on improving the health of older adults in diverse populations and specifically improving health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority populations by addressing factors that underpin disparities, such as access to care.

Several factors contribute to delayed diagnosis and management of dementia in diverse populations, some of which are not unique to minority communities. These include lack of knowledge in diagnosing dementia, culturally derived stigma around mental health conditions, language barriers, desire for culturally congruent/ethnically matched services, and concern about the cultural and religious appropriateness of services.4,7 Primary care providers (PCPs) often lack the necessary training to tailor messages about cognitive concerns or dementia or in how to have conversations in culturally appropriate ways.

Shifting Detection of Cognitive Impairment to the Primary Care Setting

Primary care practice–based settings must be better equipped to perform assessments and evaluations for dementia-related syndromes. A recent study found that a majority of older adults referred for diagnostic evaluation did not follow through with this referral supporting the need for within-primary care evaluation.8 Having early and frequent conversations during annual visits or routine follow-ups are important in reducing stigma and further supporting increased understanding of the benefits of early diagnosis and in addressing conditions that may affect brain health. Chronic conditions that might affect brain health include heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, depression, and poor sleep. In addition to promoting brain health, early diagnosis may provide opportunity for treatment of conditions that may contribute to worse brain function and cognitive symptoms such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiencies, or poorly controlled diabetes. Earlier diagnosis also facilitates advanced care planning.

The Kickstart-Assess-Evaluate-Refer (KAER) framework created by the Gerontological Society of America (GSA) was developed specifically for use by PCPs. It identifies 4 steps to increase cognitive awareness, detection of cognitive impairment, diagnosis and postdiagnostic referrals, and medical care in the context of a busy primary care setting.9 Fears and misunderstandings surrounding cognitive decline in later life make communication regarding dementia challenging. Patients and/or their caregivers may not initiate concerns about cognitive changes, and may only do so when asked. The KAER toolkit includes methods for initiating and managing conversations with patients and families about cognitive impairment and dementia; links to videos for patients and families; and online materials for providers to engage patients and their families. Providers can incorporate components of the toolkit for use during the Medicare annual wellness visit. Moreover, KAER includes essential tools for a variety of practice settings to assist in dementia-related care covering the spectrum of care processes.

Introducing, Defining, and Refining the Role of Community Organizations

Local community-based organizations (CBOs) have an established presence, trust and outreach within the community that facilitates reach to racial/ethnic and immigrant older adults and their caregivers. CBOs are ideal partners for promoting healthful behaviors among racial/ethnic and immigrant groups.8,10-13 In addition, culturally sensitive community organizations can reduce stress, depression, and social isolation for community members and their families. Further our group, the New York University Center for the Study of Asian American Health (NYU CSAAH) has demonstrated that health promoting activities are feasible, acceptable, and sustainable by immigrant-serving CBO leadership and members.14-18 For these reasons, CBOs are ideally situated to play an essential role in dementia care by providing education, addressing social needs, and creating a supportive environment for diverse adults.

Despite these advantages, referrals by CBOs may not be viewed as a priority for primary care providers, the availability of resources may be unknown, or connections may not occur due to the time constraints of a busy practice or systematic barriers. KAER emphasizes the importance of building community relationships through identifying local CBOs who can offer support and resources for persons living with dementia and their caregivers. When providers collaborate with CBOs rather than simply using them as a referral source, benefits to patients and their families may exponentially increase. For those from minority communities, the benefit may be even greater. Community-clinical coordinated care creates a bidirectional relationship in which CBOs can leverage their culturally and linguistically congruent relationships with individuals to help primary care providers address cultural stigmas of dementia care. Providers can work with CBOs to facilitate further evaluation and supportive care.

Our group, NYU CSAAH, set out to culturally adapt and translate KAER to support earlier detection of dementia in Asian American communities. In doing so, we recognized that making changes in underresourced communities requires reenvisioning the continuum of dementia care to include not only primary care providers but also the strengths and assets of CBOs. While adapting KAER, we partnered with 3 CBOs that serve as senior centers and/or adult day service centers: India Home, Korean Community Services, and Hamilton-Madison House, which serve the Asian American community. These, CBOs are often the first point of contact for concerns around cognitive impairment for the respective communities they serve. While CBO staff did not feel that they have the requisite knowledge or training to administer psychometric testing to formally assess for dementia, they did recognize their close familiarity with participants’ health and functional status. During discussions they shared case examples of situations in which they identified, with confidence, cognitive changes in older adult clients based on serial clinical observations. A major strength of these centers is that when presented with individuals experiencing or at risk for cognitive impairment, the CBO has the capacity to provide culturally appropriate group education that focuses on whole group quality of life, rather than singling out any individual. They also offer holistic family-centered care approaches and CBO staff have a deep understanding of cultural and social assets and challenges that influence care, including family dynamics.

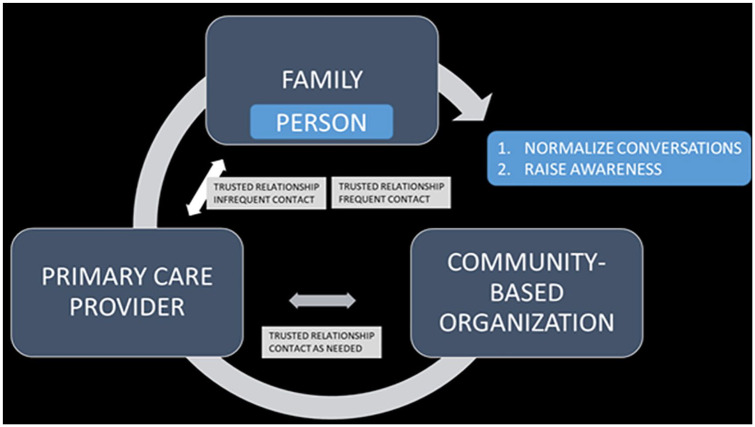

For PCPs confronting the challenge of delivering evidence-based dementia care in the context of the busy primary care settings, CBOs can be key partners in supporting earlier identification of AD/ADRD, through routine daily monitoring, and earlier entry into treatment, through referrals and care coordination, especially for minority groups. Ethnic minorities trust community centers, like the ones we worked with, and rely on them to help them access key resources (eg, health insurance, nutrition services, education). CBOs act as a pipeline to formal dementia care. They can leverage culturally and linguistically congruent relationships with those they serve to “Kickstart” the conversation around dementia and deliver education that supports informed provider/patient encounters. Given the frequency and regularity with which older adults attend senior centers and adult day centers, these CBOs can offer primary care providers detailed insight into changes in health, behavior, or functional status based on serial observations. They can also offer health care providers rich context surrounding patients’ personal life and challenges that may affect treatment. In turn, CBOs can help patients and their families understand and carry out the primary care providers’ plan of care. Although not embedded within the KAER toolkit, we recommend that providers routinely ask patients about community resources that they engage with, whether it be senior centers, adult day service programs, or religious organizations. This creates an opportunity for collaboration, if the patient is already engaged with a CBO, or presents an opportunity to link patients to resources if they lack access to culturally appropriate community-based care. One innovative example is the CommunityRx system,19 which uses e-prescribing to strengthen links between clinics and community resources for wellness and disease self-management. We also encourage providers to establish a point of contact at the CBO, with the patient’s permission, and ask about their concerns and observations. This individual may not necessarily be a clinician (eg, registered nurse or social worker). However, others, such as program directors and activity coordinators, may have invaluable day-to-day information on patients’ health and function that can help providers establish a baseline. Providers can also direct these staff members to accessible resources to implement programs, like memory training, within daily activities to establish routines and productive engagement. If participants do not have access to steady community-based care, KAER recommends providers reach out to organizations such as CaringKind (https://www.caringkindnyc.org/), the Alzheimer’s Association (https://www.alz.org/), and local universities that offer specialized and in-language services. Once a relationship has been created, maintaining an open line of communication with CBO staff is critical. It is also imperative that providers offer updates to CBO staff with regard to changes or gaps in care, and for both providers and CBO staff to engage in a discussion around what meaningful clinical information each group can contribute to establish the highest standard of care for the individual. Regular communication between PCPs and CBOs may reinforce needed care, normalize conversations around AD/ADRD at the patient and community level, foster early detection of cognitive decline, and raise awareness (Figure 1). This relationship should, therefore, be a standard part of dementia care within minority communities.

Figure 1.

The dementia care continuum for minority populations—a continuous feedback loop that includes community-based organizations.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/ or publication of this article: National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities grant award U54 MD000538; National Institutes of Health/ National Institute on Aging grant award R24 AG063725; National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Science grant award UL1TR001445.

ORCID iD: Tina R. Sadarangani  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6161-7758

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6161-7758

References

- 1. Brookmeyer R, Abdalla N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of preclinical and clinical Alzheimer’s disease in the United States. Alzheimers Dementia. 2018;14:121-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mather M, Jacobsen LA, Pollard KM. Aging in the United States. Popul Bull. 2015;70(2):1-23. https://www.prb.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/aging-us-population-bulletin-1.pdf. Accessed April 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chodosh J, Thorpe LE, Trinh-Shevrin C. Changing faces of cognitive impairment in the US: detection strategies for underserved communities. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:842-844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kenning C, Daker-White G, Blakemore A, Panagioti M, Waheed W. Barriers and facilitators in accessing dementia care by ethnic minority groups: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. National Institute on Aging. Aging well in the 21st century: strategic directions for research on aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/about/aging-well-21st-century-strategic-directions-research-aging. Accessed April 11, 2020.

- 6. United States Department of Health and Human Services. National plan to address Alzheimer’s disease: 2019. update. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/national-plan-address-alzheimers-disease-2019-update. Accessed April 11, 2020.

- 7. Parveen S, Peltier C, Oyebode JR. Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: a scoping exercise. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:734-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cadge W, Ecklund EH. Immigrants and religion. Annu Rev Sociol. 2007;33:359-379. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maslow K. Toolkit to assist primary care practitioners with the recommended 4-step KAER process. Innov Aging. 2017;1(suppl 1):609-610. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foley MW, Hoge DR. Religion and the New Immigrants: How Faith Communities Form Our Newest Citizens. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Warner RS, Wittner JG. Gatherings in Diaspora: Religious Communities and the New Immigration. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang EJ, Chung HK, Kim WY, Bianchi L, Song WO. Chronic diseases and dietary changes in relation to Korean Americans’ length of residence in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:942-950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sadarangani TR, Beasley JM, Yi SS, Chodosh J. Enriching nutrition programs to better serve the needs of a diversifying aging population. Fam Community Health. 2020;43:100-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arista P, Tepporn E, Kwon SC, et al. Recommendations for implementing policy, systems, and environmental improvements to address chronic diseases in Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E202. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel S, Kwon SC, Arista P, et al. Using evidence-based policy, systems, and environmental strategies to increase access to healthy food and opportunities for physical activity among Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 3):S455-S458. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pollack HJ, Kwon SC, Wang SH, Wyatt LC, Trinh-Shevrin C; AAHBP Coalition. Chronic hepatitis B and liver cancer risks among Asian immigrants in New York City: results from a large, community-based screening, evaluation, and treatment program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:2229-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li S, Sim SC, Lee L, et al. Hepatitis B screening & vaccination behaviors in a community-based sample of Chinese & Korean Americans in New York City. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41:204-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Trinh-Shevrin C, Pollack HJ, Tsang T, et al. The Asian American hepatitis B program: building a coalition to address hepatitis B health disparities. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2011;5:261-271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lindau S, Makelarski J, Abramsohn E, et al. CommunityRx: a population health improvement innovation that connects clinical to communities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:2020-2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]