Abstract

Introduction

There is an unmet need to develop tailored therapeutic exercise protocols applying different treatment parameters and modalities for individuals with knee osteoarthritis (KOA). Cryotherapy is widely used in rehabilitation as an adjunct treatment due to its effects on pain and the inflammatory process. However, disagreement between KOA guidelines remains with respect to its recommendation status. The aim of this study is to verify the complementary effects of cryotherapy when associated with a tailored therapeutic exercise protocol for patients with KOA.

Methods and analysis

This study is a sham-controlled randomised trial with concealed allocation and intention-to-treat analysis. Assessments will be performed at baseline and immediately following the intervention period. To check for residual effects of the applied interventions, 3-month and 6-month follow-up assessments will be performed. Participants will be community members living with KOA divided into three groups: (1) the experimental group that will receive a tailored therapeutic exercise protocol followed by a cryotherapy session of 20 min; (2) the sham control group that will receive the same regimen as the first group, but with sham packs filled with dry sand and (3) the active treatment control group that will receive only the therapeutic exercise protocol. The primary outcome will be pain intensity according to a Visual Analogue Scale. Secondary outcomes will be the Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index; the Short-Form Health Survey 36; the 30-s Chair Stand Test; the Stair Climb test; and the 40-m fast-paced walk test.

Ethics and dissemination

The trial was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Federal University of São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil. Registration approval number: CAAE: 65966617.9.0000.5504. The results will be published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

Keywords: pain management, rehabilitation medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The trial will be conducted according to well-established reporting guidelines.

Participants will present radiographically confirmed knee osteoarthritis and a sufficient level of pain to ensure ample scope for improvement.

The trial will use both subjective and objective outcome measures of physical function.

The therapist who delivers cryotherapy or the sham intervention and the patients will not be blinded.

The loss to follow-up after randomisation in the sham group might be higher than those in the other groups.

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a serious disease with a high societal and economic burden,1 affecting approximately 250 million people worldwide.2 Current clinical practice guidelines recommend a combination of pharmacological3 and non-pharmacological4 treatment strategies to manage KOA symptoms and improve patients’ quality of life. However, pharmacological treatment options that have been proven to relieve symptoms remain limited, and some of the most commonly recommended pharmacological treatments are poorly tolerated, with long-term use resulting in serious systemic adverse events.5–7

Physical therapy, specifically the use of strengthening therapeutic exercise (STE) protocols, have been shown to relieve pain, reduce stiffness, increase physical function and improve quality of life in patients with KOA.1 8 High-quality evidence has demonstrated that the benefits of STE protocols on pain and quality of life in individuals with KOA are sustained for at least 2–6 months after the end of a treatment.8 There is; however, a call for further research to develop novel insights within STE protocols regarding differences in treatment durations, frequencies, modalities and intensities.9 The majority of current protocols have reported low adherence and are substantially under-used by patients with KOA, mainly due to socioeconomic barriers, personal beliefs, fear of movement and aggravation of pain in the early phases of treatment.10 11 Therefore, there is an unmet need for cost-effective, evidence-based STE protocols that are tailored to the needs of patients with KOA, and that can aid clinicians in targeting rehabilitation goals.

Physical modalities such as thermal agents, laser therapy, therapeutic ultrasound and electrical stimulation are often used as adjunct treatments with therapeutic exercises in individuals with KOA.4 12 Cryotherapy, a non-pharmacological intervention, has been widely used in some rheumatic joint diseases13,14 based on its effects on pain, inflammation and oedema.15 16 In an animal model with induced KOA, clinical-like cryotherapy was beneficial to reduce the synovial inflammation due to lower leukocyte migration to the knee joint cavity and inflammatory cytokine concentration.17 Cryotherapy is considered safe, and is inexpensive and easy to administer for healthcare professionals and patients. Moreover, it can be prescribed in isolation or as an adjunct treatment and seems to be well accepted by individuals with KOA.14 18 19 Although cryotherapy is recommended as a treatment option by some international KOA guidelines,20 21 others have found insufficient evidence to support it.22–24 Relevant systematic reviews have likewise concluded that further evidence, produced with greater methodological rigour, is needed to evaluate the effects of cryotherapy on pain, function and quality of life in individuals with KOA.16 25

In this study, we aim to design a randomised trial to verify the complementary effects of cryotherapy in conjunction with a tailored STE protocol on pain, function and quality of life in individuals with KOA. We hypothesise that cryotherapy combined with the STE protocol will achieve better treatment effects on patients with KOA when compared with the other two groups. The proposed trial will contribute to new evidence to the physical therapy field in KOA by focusing on interventions that target rehabilitation and enhance pain management, thereby improving the physical function and quality of life of these patients. Our research group developed the STE protocol described in this study. The protocol was also used in another randomised trial, testing the complementary effects of Photobiomodulation in individuals with KOA (trial registration number at www.ensaiosclinicos.gov.br: U1111-1215-6510). This manuscript has been submitted simultaneously with the manuscript entitled ‘Photobiomodulation therapy associated with supervised therapeutic exercises for people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised controlled trial protocol.

Methods

To report this study protocol, we followed the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials,26 the Osteoarthritis Research Society International clinical trials recommendations: design, conduct and reporting of clinical trials for KOA,27 and the template for intervention description and replication checklist.28 The randomised trial will be reported according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials statement for randomised trials of non-pharmacological treatments.29

Study design and setting

This study is a single-centre, sham-controlled randomised clinical trial. A baseline assessment (A1) will be performed on the week day before the 8-week intervention period, and a postintervention assessment (A2) will be performed immediately following the last session. To check for residual effects of the interventions, 3-month (A3) and 6-month (A4) follow-up assessments will be performed. Each patient will be assessed in a physiotherapy research laboratory, during the same period of the day and by the same assessor. To reduce bias, the therapists responsible for applying the intervention and the outcome assessors will follow standardised scripts that describe the general objective of the study.27

Intervention adherence, medication intake and possible adverse events will be tracked with an 8-week assessment diary that will be given to participants at the baseline assessment and with a 12-week assessment diary for the 3 month follow-up assessment. All the participants will be advised not to practice any other type of regular physical exercise during the course of the study that could interfere with the STE protocol. A verbal and written explanation of the objectives and methodology of the study will be provided to all the participants, and those willing to participate will sign a written informed consent form, approved by the local ethics committee. A detailed timeline of the trial is presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Timeline of the measurements to be taken at each point on the trials

| Timeline | Enrolment | STE protocol training | Baseline assessment (A1) |

Intervention | Postintervention assessment (A2) |

Follow-up assessment (A3) |

Follow-up assessment (A4) |

| −2 weeks (–14 to −7 days) |

−1 week (–7 to 0 day) |

Day 0 | 8 weeks (±3 days) |

20 weeks (±3 days) |

32 weeks (±3 days) |

||

| Enrolment | |||||||

| Eligibility screen | X | ||||||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||

| Interventions | |||||||

| Allocation | X | ||||||

| STE | X | ||||||

| STE+cryotherapy | X | ||||||

| STE+sham cryotherapy | X | ||||||

| X-ray examination of both knees | X | ||||||

| Assessments | |||||||

| VAS | X | X | X | X | |||

| WOMAC | X | X | X | X | |||

| SF-36 | X | X | X | X | |||

| Timed-up and Go Test | X | X | X | X | |||

| 30 s chair to stand test | X | X | X | X | |||

| Stair climb test | X | X | X | X | |||

| 40 m (4×10 m) fast paced walk test | X | X | X | X | |||

A, assessment; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; SF-36, Short Form-36 questionnaire.STE, Strength therapeutic exercises; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale, WOMAC: Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis questionnaire.

Patient and public involvement

The patients and the public were not involved in the planning and design of this study.

Participants

Participants will be recruited through public announcements on social media, advertisements via local news outlets, university community newsletters and banners or leaflets posted at strategic locations in the city. People who are interested in participating in the study will first be screened to check the eligibility criteria. Eligible participants will then undergo a lateral, anteroposterior and axial radiography of both knees to determine KOA structural severity, which will take place at the University Hospital. Participants will be classified with KOA based on the clinical and radiographic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology,30 and will be required to have symptoms and a radiographic grade (Kellgren and Lawrence scale) of ≥2 (mild radiographic OA) in at least one knee compartment.27

To be included in the study, participants will also need to: be between 40 and 75 years old; be engaged in a total of less than 45 min/week of physical activity of at least moderate intensity;31 have a body mass index <35 kg/m2 and to have reported pain intensity in the prior week of ≥4 cm on a 10 cm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).27 Exclusion criteria will comprise physical therapy in the prior 3 months; intra-articular knee injections in the prior 6 months; medical restrictions such as cardiorespiratory, neurological or any other rheumatology conditions; previous hip, knee or ankle surgery and any other chronic condition that leads to chronic painor dysfunction. Additionally, participants presenting with contraindication(s) to cryotherapy application (ie, those that feel a high level of discomfort or pain during the application) will be excluded.

All the participants will be asked to provide a medical certificate stating that they are healthy enough to perform physical activities before the start of the intervention.

Interventions

The cryotherapy intervention protocol is based on a previously accepted methodology developed in our research laboratory.32 Two physical therapists will administer the interventions in the physiotherapy clinic of the university. The study will take place over the course of 8 weeks, with three 90-min sessions per week occurring on non-consecutive days, for a total of 24 sessions. All randomised participants will perform the STE protocol and then, according to random allocation, each patient will subsequently receive either cryotherapy or sham interventions in individual rooms.

Prior to the beginning of the study, the therapists responsible for the interventions will participate in a 10 hours training module, which will consist of scientific information and clinical training regarding KOA, the STE protocol and the use of cryotherapy. After the first training module is completed, the therapists will do an 8-week training module, which will consist of practicing the full-length protocol and intervention application(s) three times per week. Both therapists will be responsible for delivering cryotherapy and sham interventions.

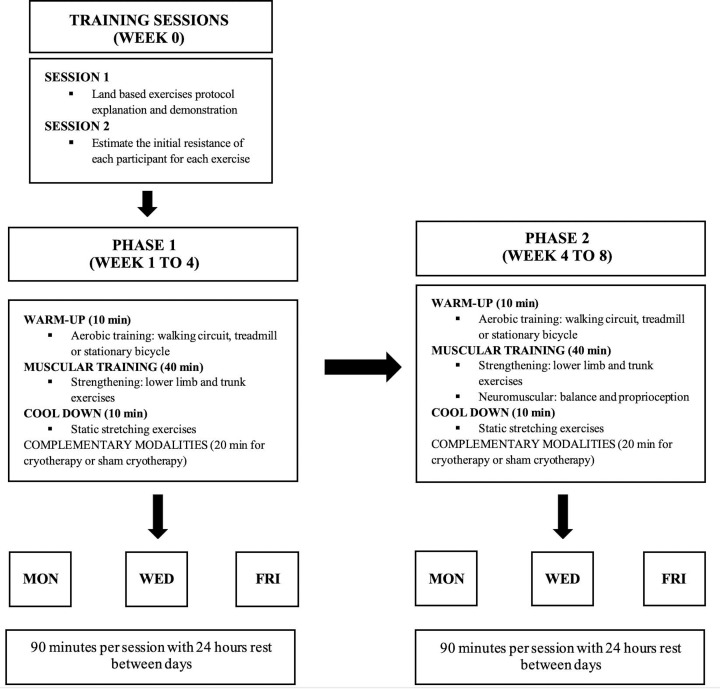

STE protocol

We designed the 8-week land-based supervised exercise protocol according to the evidence-based recommendations for physical exercise interventions in KOA.33 34 The STE protocol characteristics are described in figure 1, and a detailed description of all the exercises is presented in the online supplementary file 1 of this protocol. The protocol is divided into two phases. Each phase consists of 4 weeks of progressive exercises, performed three times per week on non-consecutive days (24 hours rest between sessions), with exercise intensity individually tailored for each participant. The first session is used to demonstrate and explain the STE protocol, and to perform an exercise familiarisation using no loads by the participants. The second session is designed to estimate the initial resistance of each participant for each exercise. All participants start doing the exercises using bodyweight and the volitional interruption method is used in order to achieve the benefits of resistance training and to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries.35 The loads are gradually increased until the participant can adequately perform 12 repetitions with no voluntary interruption due to muscle fatigue.

Figure 1.

Land based exercise protocol characteristics

bmjopen-2019-035610supp001.pdf (50.5MB, pdf)

The STE protocol sessions consist of three main activities. The first activity is a 10-min warm-up in which the patients can choose, according to their preferences, to walk in a comfortable intensity in an outdoor circuit, treadmill or ride in a stationary bicycle. The second activity consists of 40-min of strengthening exercises, such as lower limb and trunk exercises and neuromuscular training involving balance exercises. The third activity is a 10-min cool-down cycle, consisting of static stretching exercises to reduce the risk of musculoskeletal injuries and to maximise the benefit of the STE protocol.36 To ensure patient safety, cardiac and respiratory frequencies and blood pressure are monitored if the participant presents an intense rate of perceived exertion according to the Borg scale while performing an exercise.37 38

Cryotherapy protocol

To apply cryotherapy, the therapist will explain to the patient that the intervention will consist of crushed ice applied to the more-affected knee for 20 min. Participants will be positioned in dorsal decubitus with both legs extended and relaxed. The entire knee surface will be covered with a moist surgical gauze (45×50×0.01 cm) to protect the skin from possible frostbite. Next, two plastic bags (24×34×0.08 cm), each containing 1 kg of crushed ice, will be placed on the knee, covering the anterior, posterior, medial and lateral surfaces. A comfortable, non-painful compression will be applied over the ice packs by wrapping an elastic bandage around them, and the therapy will be left in situ, uninterrupted, for 20 min. The primary purpose of compression is to maintain the ice packs in position on the knee39 and to enhance cryotherapy effects.40

For the sham cryotherapy intervention, the bags will be filled with 1 kg of dry sand instead of ice. The sandbags will be applied according to the same regimen in the same locations. The therapist’s explanation about the intervention will be changed to mention the ‘application of sand packs’ instead of ‘cryotherapy application.’ The sandbags will be applied with the same gauze underneath and the same bandage for compression.

Outcome measures

The same blinded assessor will measure all outcomes before and after the intervention, and at the 3-month and 6-month follow-up periods. Before the study begins, the two outcome assessors will be trained to conduct interviews and perform data collection following a standard protocol. Table 2 describes the outcome measures that will be included in the trial and the recommended estimate of the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for each outcome measure. We will measure pain intensity, subjective and objective physical function and quality of life.

Table 2.

Description of the outcome measures

| Outcome measure | Description of the test | Scoring | Minimum clinically important difference (MCID) |

| Visual Analogue Scale | The scale is positioned in front of the patient who is asked to evaluate pain intensity in the prior week.41 | The scale ranges from 0 (no pain) to 10 cm (maximum pain intensity). | A pain reduction of 1.75 cm is recommended in OA research.49 |

| Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis questionnaire | This self-report questionnaire evaluates the difficulties experienced by individuals with lower limb OA in the prior 72 hours. It contains 24 questions in three domains: pain, stiffness and physical function. | Each question is scored from 0 to 4, and the maximum score possible is 96. The higher the scores, the worse the status of a patient. | An improvement of 12% from baseline is recommended in OA research.52 |

| Short-Form-Health Survey 36 (SF-36) | The short form questionnaire is intended to measure the patient’s quality of life with 36 items referring to the past 4 weeks. It presents a multiple-choice scale that evaluates eight domains of life: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical problems, general health perceptions, vitality, social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems, general mental health and health transition. | The sum of the total value varies from 0 to 100, with higher indexes indicating a better quality of life. Each of the eight summed scores was linearly transformed into a scale from 0 (negative health) to 100 (positive health) to provide a score for each subscale. Each subscale was used independently. | A difference of 10 points is recommended as an MCID in OA research.53 |

| Stair climb test | The participant is positioned in front of the stairs. At the therapist’s signal, he/she has to climb the indicated steps (we used the 12-step SCT) and descend promptly, being able to use the handrail as a security instrument. We used 20 cm steps height, a handrail stair in an lighted environment, free of traffic, or external distractions. Moreover, a pretest was conducted to identify the need for safety measures. | The final score is calculated based on the time the participant took to perform the test and compared it to the literature normative values of the test. | A reduction of 5.5 s in the test is the recommended MCID in OA research44 |

| 40 m (4×10 m) Fast paced walk test | Administered at a distance of 10 m (marked by tapes), a cone is placed 2 m before the start and 2 m after the end of each marking. The participant is instructed to walk as quickly but as safely as possible the first 10 m (from the start mark), to turn around in the cone and walk back the 10 m again, successively until completing the distance of 40 m. | Speed (m/s) | An increase of 0.2–0.3 m per second in the test is the recommended MCID in OA research44 |

| 30 s Chair to stand test | A chair with no arms is placed against a wall to prevent oscillations. Patients sit in the middle of the chair, with their back straight and feet resting on the floor in line with their shoulders. The participant is asked to rise from sitting to standing as many times as possible in 30 s. | Total number of repetitions within 30 s | An increase of 2 to 3 repetitions is recommended in OA research.54 |

OA, osteoarthritis.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be pain intensity at rest, assessed with a VAS. This self-reported pain score is a valid and reliable measure for KOA.41 The VAS will be administered at rest and after each physical function test, occurring at baseline, on the final assessment day and at the 3-month and 6-month follow-up periods.

Secondary outcomes

To subjectively assess physical function and associated problems, the Western Ontario & McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) will be used. The WOMAC is a frequently used questionnaire in KOA and is translated, reproducible and valid to Brazilian Portuguese.42 The Short-Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) will be used to asses quality of life. The questionnaire is translated, reproducible and valid to use in Brazilian Portuguese.43 Three objective physical function tests will also be used: the 30 s chair stand test, the stair climb test and the 40-m fast-paced walk test. The questionnaires and physical function tests described are well-established core assessment measures of pain and physical function in patients with KOA, and present good scores for reliability, validity and ability to detect change.44–48

Randomisation

Eligible patients who consent to participate will be randomly allocated into three groups of 40: (1) active control group that will receive the STE protocol only, (2) STE+cryotherapy group and (3) STE+sham cryotherapy group. The allocation of patients will be performed using permuted block randomisation stratified by gender (20 men and 20 women in each group); randomisation sequences will be determined by a computer-generated random numbers programme (www.randomization.com). Allocation will be concealed by placing randomisation assignments in opaque sealed envelopes that will be locked in a central location. A biostatistician will be responsible for generating the random numbers and each participant’s random allocation will be revealed to the therapist administering the intervention just before study onset.27

Sample size

We aim to detect a MCID of 1.75 cm units on the VAS for pain intensity at rest.49 Also, we aim to detect an MCID of 30 points on the WOMAC global score.50 Calculations were based on an analysis of covariance adjusting for baseline outcome scores, assuming between-patient SD of 2.0 cm for pain and 45 points for WOMAC global score. Based on these criteria, to achieve a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.80%, 37 participants with KOA will be required in each group. We will recruit 40 participants per group to allow possible dropouts during the intervention period.

Data analysis

The analyses will be performed by a blinded biostatistician using commercial software. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test will be applied to evaluate the normality of data distribution. If the distribution is not normal, non-parametric tests will be used. For normal distributions, a 2-factor analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be conducted for the primary outcome (VAS for pain) and secondary outcomes, with time (baseline, postintervention and follow-up) as the within-subject factor and group (STE, STE+cryotherapy and STE+sham cryotherapy) as the between-subject factor. In addition, Tukey’s test will be used for post-hoc analysis when necessary, and an intention-to-treat analysis will be performed for all randomised participants. All the missing data will be replaced using the expectation-maximisation method. Between-group differences and their 95% CIs will be reported and interpreted against the nominated thresholds for MCID. For the outcomes where the MCID is not nominated, Cohen’s d coefficient will be calculated to aid interpretation. An effect size greater than 0.8 will be considered large, around 0.5 moderate, and less than or equal to 0.2, small.51

Ethics and dissemination

The Institutional Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil, approved the study under the registration approval number: CAAE: 65966617.9.0000.5504. The trial will be conducted according to the Helsinki Statement. All participants will provide written informed consent following a verbal and written explanation of the study protocol. Participants will be free to withdraw from the trial at any time without prejudice to future treatment. Results will be presented at scientific meetings and published in peer-reviewed journals. All publications and presentations related to the study will be authorised and reviewed by the study investigators.

Trial status

The trial is currently recruiting and is expected to be completed (including follow-up testing) by December 2020.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LOD, AESJ, PRS, FAS and TFS designed the study protocol. LOD wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and together with AESJ, PRS, FAS and TFS revised and produced the final version. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. LOD takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Funding: LOD and AESJ were financially supported by Sao Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, Process numbers #2015/21422-6, and #2017/00062–7, respectively) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Process 1662695 - 001). TFS is a Researcher of Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ #302169/2018).

Disclaimer: The study funders have had no role in study design; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data; writing of the report or the decision to submit the report for publication, and do not own ultimate authority over any of these activities.

Competing interests: None declared

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S. Osteoarthritis. Lancet 2019;393:1745–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mandl LA. Osteoarthritis year in review 2018: clinical. Osteoarthr Cartil 2018;xxxx:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Collins NJ, Hart HF, Mills KAG. OARSI year in review 2018: rehabilitation and outcomes. Osteoarthr Cartil 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vowles KE, McEntee ML, Julnes PS, et al. Rates of opioid misuse, abuse, and addiction in chronic pain: a systematic review and data synthesis. Pain 2015;156:569–76. 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460357.01998.f1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid Abuse in Chronic Pain--Misconceptions and Mitigation Strategies. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1253–63. 10.1056/NEJMra1507771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deveza LA, Hunter DJ, Van Spil WE. Too much opioid, too much harm. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2018;26:293–5. 10.1016/j.joca.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fransen M, Mcconnell S, Ar H. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Libr 2015;1:1–144. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee AC, Harvey WF, Price LL. Dose-Response effects of tai chi and physical therapy exercise interventions in symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. PM&R 2018;10:712–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nicolson PJA, Bennell KL, Dobson FL, et al. Interventions to increase adherence to therapeutic exercise in older adults with low back pain and/or hip/knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:791–9. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dobson F, Bennell KL, French SD, et al. Barriers and facilitators to exercise participation in people with hip and/or knee osteoarthritis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2016;95:1 10.1097/PHM.0000000000000448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WM O, Thae Bo M. Efficacy of physical modalities in knee osteoarthritis: recent recommendations. Int J Phys Med Rehabil 2016;04:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Demoulin C, Vanderthommen M. Cryotherapy in rheumatic diseases. Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:117–8. 10.1016/j.jbspin.2011.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guillot X, Tordi N, Mourot L, et al. Cryotherapy in inflammatory rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2014;10:281–94. 10.1586/1744666X.2014.870036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bleakley CM, Davison GW. Cryotherapy and inflammation: evidence beyond the cardinal signs. Physical Therapy Reviews 2010;15:430–5. 10.1179/1743288X10Y.0000000014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dantas LO. Moreira R de Fc, Norde FM, Mendes Silva Serrao PR, Alburquerque-Sendín F, Salvini TF. The effects of cryotherapy on pain and function in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2019:026921551984040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barbosa GM, Cunha JE, Cunha TM, et al. Clinical-like cryotherapy improves footprint patterns and reduces synovial inflammation in a rat model of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 2019;9 10.1038/s41598-019-50958-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Porcheret M, Jordan K, Jinks C, et al. Primary care treatment of knee pain--a survey in older adults. Rheumatology 2007;46:1694–700. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Denegar CR, Dougherty DR, Friedman JE, et al. Preferences for heat, cold, or contrast in patients with knee osteoarthritis affect treatment response. Clin Interv Aging 2010;5:199–206. 10.2147/CIA.S11431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chae KJ, Choi MJ, Kim KY. National Institute for health and care excellence. Osteoarthritis: Care and Management, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:465–74. 10.1002/acr.21596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McAlindon TE, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:363–88. 10.1016/j.joca.2014.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1125–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil 2017;31:596–611. 10.1177/0269215517691084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Brosseau L, a YK, Robinson V. Thermotherapy for treatment of osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;4:CD004522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Spirit 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McAlindon TE, Driban JB, Henrotin Y, et al. OARSI clinical trials recommendations: design, conduct, and reporting of clinical trials for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2015;23:747–60. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014;348:g1687. 10.1136/bmj.g1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Barbour V, Bhui K, Chescheir N, et al. Consort statement for randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: a 2017 update and a consort extension for nonpharmacologic trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:40–7. 10.7326/M17-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. diagnostic and therapeutic criteria Committee of the American rheumatism association. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039–49. 10.1002/art.1780290816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dunlop DD, Song J, Lee J, et al. Physical activity minimum threshold predicting improved function in adults with lower-extremity symptoms. Arthritis Care Res 2017;69:475–83. 10.1002/acr.23181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dantas LO, Breda CC, da Silva Serrao PRM, et al. Short-Term cryotherapy did not substantially reduce pain and had unclear effects on physical function and quality of life in people with knee osteoarthritis: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2019;65:215–21. 10.1016/j.jphys.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Messier SP, Mihalko SL, Beavers DP, et al. Strength training for arthritis trial (start): design and rationale. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:208. 10.1186/1471-2474-14-208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fransen M, McConnell S, Harmer AR, et al. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1554–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nóbrega SR, Ugrinowitsch C, Pintanel L, et al. Effect of resistance training to muscle failure vs. volitional interruption at high- and Low-Intensities on muscle mass and strength. J Strength Cond Res 2018;32:162–9. 10.1519/JSC.0000000000001787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bennell KL, Dobson F, Hinman RS. Exercise in osteoarthritis: moving from prescription to adherence. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014;28:93–117. 10.1016/j.berh.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. American Geriatrics Society Panel on Exercise and Osteoarthritis Exercise prescription for older adults with osteoarthritis pain: consensus practice recommendations. A supplement to the AGS clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic pain in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:808–23. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.00496.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vincent KR, Vincent HK. Resistance exercise for knee osteoarthritis. Pm R 2012;4:S45–52. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2012.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fousekis K, Billis E, Matzaroglou C, et al. Elastic bandaging for Orthopedic- and Sports-Injury prevention and rehabilitation: a systematic review. J Sport Rehabil 2017;26:269–78. 10.1123/jsr.2015-0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Song M, Sun X, Tian X, et al. Compressive cryotherapy versus cryotherapy alone in patients undergoing knee surgery: a meta-analysis. Springerplus 2016;5:1–12. 10.1186/s40064-016-2690-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, et al. Measures of adult pain: visual analog scale for pain (vas pain), numeric rating scale for pain (NRS pain), McGill pain questionnaire (MPQ), short-form McGill pain questionnaire (SF-MPQ), chronic pain grade scale (CpGs), short Form-36 bodily pain scale (SF-36 BPs), and measure of intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res 2011;63 Suppl 11:S240–52. 10.1002/acr.20543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. MI F. Tradução E validação do questionário de qualidade de vida específico para osteoartrose WOMAC (Western Ontario McMaster universities) para a língua portuguesa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos W. Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SF-36. A reliable and valid quality of life outcome measure. Rev Bras Reumatol 1999;39:143–50. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dobson F, Bennell KL, Hinman RS. Recommended performance - based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. OARSI - Osteoarthr Res Soc Int 2013:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC. American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheum 2020:art.41142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2019;27:1578–89. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pham T, van der Heijde D, Altman RD, et al. OMERACT-OARSI initiative: osteoarthritis research Society international set of Responder criteria for osteoarthritis clinical trials revisited. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:389–99. 10.1016/j.joca.2004.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bennell K, Dobson F, Hinman R. Measures of physical performance assessments: Self-Paced Walk Test (SPWT), Stair Climb Test (SCT), Six-Minute Walk Test (6MWT), Chair Stand Test (CST), Timed Up & Go (TUG), Sock Test, Lift and Carry Test (LCT), and Car Task. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63 Suppl 11:S350–70. 10.1002/acr.20538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bellamy N, Carette S, Ford PM, et al. Osteoarthritis antirheumatic drug trials. III. Setting the delta for clinical trials--results of a consensus development (Delphi) exercise. J Rheumatol 1992;19:451–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fitzgerald GK, Fritz JM, Childs JD, et al. Exercise, manual therapy, and use of booster sessions in physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis: a multi-center, factorial randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1340–9. 10.1016/j.joca.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cohen J. LE HNJ, ed Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd edn, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G. Smallest detectable and minimal clinically important differences of rehabilitation intervention with their implications for required sample sizes using WOMAC and SF-36 quality of life measurement instruments in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower extremities. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Escobar A, Quintana JM, Bilbao A, et al. Responsiveness and clinically important differences for the WOMAC and SF-36 after total knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2007;15:273–80. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2013;21:1042–52. 10.1016/j.joca.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035610supp001.pdf (50.5MB, pdf)