Abstract

Over 30 key leaders in the field participated in a 1-day workshop entitled ‘Recent Advances and Opportunities in the Development and Use of Humanized Immune System Mouse Models’ to discuss the benefits and limitations of using human fetal tissue versus non-fetal tissue sources to generate mice with a humanized immune system. This Comment summarizes the workshop discussions, including highlights of some of the key advances made through the use of humanized mice in improving the understanding of immune system function and developing novel therapeutics for the treatment of infectious, immunological and allergic diseases, as well as current challenges in the production, characterization and utilization of these animal models.

Humanized mouse models

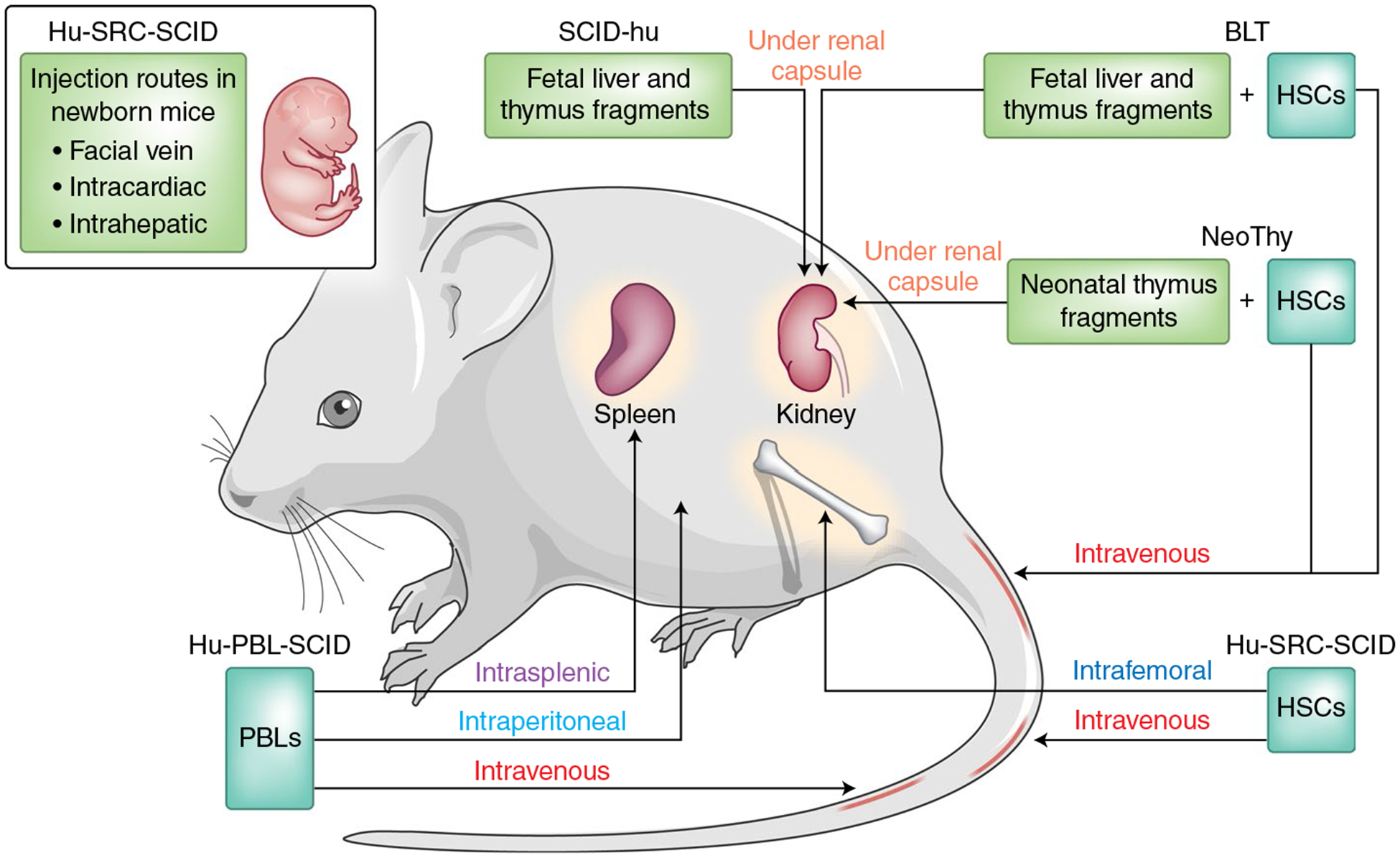

Immunocompetent mice are widely used in biomedical research, and use of such mice has supported many advances across multiple scientific disciplines. However, critical differences in the genetics and immune systems of mice and those of humans have precluded studies in mice of uniquely human immune responses. One way to address these species-specific differences is to conduct in vivo preclinical studies using immunodeficient mice engrafted with human cells or tissues — i.e., ‘humanized’ mice or ‘human immune system’ (HIS) mice (Fig. 1). These humanized mice engrafted with human cells and tissues serve as a preclinical bridge for several research areas. Engraftment of immunodeficient mice with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) or human fetal tissues (thymus and liver) began in 1988 following the discovery of the Prkdcscid (severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)) mutation on the CB17 mouse strain background1, with a focus on the development of a model for studies of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Humanized mice also have been used for testing the safety of drugs that target immunoreceptors exhibiting species-specific functionality. An example of this is therapy with antibody to the co-stimulatory receptor CD28, for which preclinical studies of non-human primates did not predict the serious adverse events observed in the first human clinical trial2.

Fig. 1 |. Humanized mouse models.

Additional information on the humanized mouse models described in the text. Hu, humanized; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte; SRC, SCID-repopulating cell; NeoThy, neonatal thymus. Adapted from ref.21.

Injection of human PBMCs is the most direct method for developing HIS mice, although the expansion of human T cells is followed by acute xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease. While the rapid development of this disease enables preclinical testing of human immunosuppressive agents, the relatively short survival of engrafted animals prevents long-term in vivo functional studies of T cells. Humanization can also be accomplished through the use of human HSCs derived from umbilical cord blood, bone marrow, fetal liver or adult mobilized HSCs. Although most HSC-engraftment models require preconditioning with sublethal X-irradiation or treatment with radiomimetic drugs such as busulfan, several newer models can support HSC engraftment without preconditioning. Improved immunodeficient mouse strains that lack mouse natural killer cell activity have been developed, such as the NOD-PrkdcscidIl2rgtmiwjl/Sz (NSG) strain and related models (NOG, NRG, BRGS, etc.) and MISTRG mice, that all support greater engraftment of human lymphoid, myeloid and hematopoietic cells than did the earlier models. MISTRG mouse models represent an improvement in the development of the innate immune system relative to that of previous strains3,4.

Despite such successes, the development of a robust functional human immune system following HSC engraftment in HIS mice has remained constrained by numerous factors, including the species specificity of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens, hematopoietic growth factors and cytokines, suboptimal development of lymphoid architecture and impaired class switching and affinity maturation of immunoglobulins.

Notably, T cell education in the thymus is restricted largely by mouse MHC (H-2 complex). The development of human MHC (HLA)–restricted T cells can be accomplished through the implantation of fetal human thymus and liver tissue along with autologous fetal liver HSCs, which results in ‘BLT’ (bone marrow, liver, thymus) mice, or through the use of NSG mice that have transgenic expression of HLA molecules and are engrafted with partially matching cord blood HSCs3. Many humanized mouse models also express human cytokines, including SCF, CSF-1, GM-CSF, IL-3, IL-6, IL-7 and IL-15, that support enhanced differentiation of human myeloid and lymphoid cell populations3. Transgenic expression of human IL-34 supports the development of human microglia and of the brain HIV-1 reservoir. Such advances are overcoming many deficiencies of the current models and facilitate the ability to address specific immunological questions (Table 1).

Table 1 |.

Summary of humanized mouse models

| Model | Mouse strain | Human tissue | Application | Investigator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanized mouse models without fetal tissue | ||||

| Neo Thy humanized mouse | NSG NBSGW |

Cryopreserved neonatal thymus Umbilical cord blood |

Immunogenicity studies | M. Brown |

| NRG-Akita | NOD-Rag1nullIl2rgnullIns2Akita | Juvenile human islets; umbilical cord blood | Islet allotransplantation | M. Brehm |

| NSG-Hu-PBL | NSG | PBMCs | HIV/AIDS (long-acting drugs); gene therapy; visualizing HIV-1 infection | P. Kumar |

| NSG-HSC | NSG | Umbilical cord blood | Arboviruses (flavivirus, alphavirus and bunyaviruses) | R. Rico-Hesse |

| NSG | Umbilical cord blood | Analysis of immunological perturbations (autoimmunity) | K.C. Herald | |

| Testing of long-acting anti-HIV therapies | L. Poluektova | |||

| NOG-hlL34 | Umbilical cord blood | Infection of human microglia with HIV | L. Poluektova | |

| NSG or NRG HIS mice | NSG, NRG | Umbilical cord blood | Study of B cell development and pediatric bacterial vaccines | T. Manser |

| Mouse viral outgrowth assay | NSG | PBMCs from HIV-infected patients | Detection of replication-competent HIV | R. Akkina |

| NOD SCID | NOD SCID B2m−/− | Adult CD34+ HSCs | Adoptive T cell transfer | K. Palucka |

| BRGS-hu | BRGS | Umbilical cord blood | Development of colorectal cancer PDX hu mice; EBV type 2 infection; B cell lymphomagenesis | R. Pelanda |

| MISTRG | Immunodeficient Rag2−/− ll2rg−/− mice with human M-CSF, IL-3, GM-CSF, TPOandSIRPα | Umbilical cord blood | Efficient development of myeloid cells and NK cells | A.Rongvaux |

| Humanized mouse models with fetal tissue | ||||

| BLT | NSG | Fetal liver and thymus | HIV/AIDS | T. Allen |

| Zika virus | R. Akkina | |||

| Comparison of biologies; cytokine-release syndrome; checkpoint inhibitor adverse events | K. Howard | |||

| Vaccine and NK cell studies | S. Paust | |||

| TKO-BLT | TKO | Fetal liver and thymus | HIV–AIDS | K. Hasenkrug |

| NSG-SGM3-BLT | NSG-SGM3 | Fetal liver and thymus | Development of human mast cells for anaphylaxis studies; human macrophage-mediated fibrosis in would healing | M. Brehm |

| NSG-HSC | NSG | HSCs from fetal liver | Mouse skin transplant model; type 1 diabetes; aberrant immune responses; microbiota control | K.C. Herald |

| NSG or NRG HIS mice | NSG, NRG | HSCs from fetal liver | Study of B cell development and pediatric bacterial vaccines | T. Manser |

| SCID-huThy/Liv | C.B-17scid | Fetal liver and thymus | Isolation of candidate human stem cell populations and CNS stem cells; growth of cancer stem cells in mice; HIV–AIDS | Weissman I |

| AFC-hu HSC/Hep | AFC8/BRG | Hepatocytes and HSCs from fetal liver | Human liver fibrosis after HCV infection | L. Su |

| A2/NSG-hu HSC/Hep | A2/NSG | Hepatocytes and HSCs from fetal liver | Human liver fibrosis after HBV infection | L.Su |

| Human microglia mouse | NOG-hlL34 | Fetal brain and liver tissue | Study of neurotropic infections, such as infection with HIV, CMV, Zika virus, JCPyV | L. Poluektova |

| Fetal human thymus mouse model | NSG | Fetal human thymus plus CD34+ cells | Study of T cell homeostasis, Treg cell development, human T cell repertoire development, transplantation tolerance, in vivo analysis of human immune responsiveness | M. Sykes |

| UCLA service core | BLT, SCID-hu, hu-PBL SCID, NOG-hu, BLT-NOD.SCID, HIS-DKO, NRG-BLT | Fetal liver and thymus | IND-enabling studies in HIV–AIDS, oncology, hematopoietic disorders, gene therapy, immunotherapy, and infectious disease | S. Kitchen |

NBSGW, NOD.Cg-KitW−41JTyr + PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1Wjl/ThomJ; TKO, B6.129S-Rag2tm1FwaCd47tm1FplIl2rgtm1Wjl/J; NRG, NOD.Cg-Rag1tm1MomIl2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ; BRGS, BALB/c Rag2tm1FwaIl2rgtm1CgnSirpaNOD; MISTRG, C;129S4-Rag2tm1.1FlvCsf1tm1(CSF1)FlvCsf2/Il3tm1.1(CSF2,IL3)FlvThpotm1.1(TPO)FlvIl2rgtm1.1FlvTg(SIRPA)1Flv/J; B2m, gene encoding β2-microglobulin; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; CNS, central nervous system; JCPyV, JC polyomavirus; KO, knockout; PDX, patient-derived xenograft; NK, natural killer; Treg cell, regulatory T cell; IND, investigational new drug.

Applications to human diseases

A few of the key areas in which humanized mice have contributed substantially to the scientific understanding of human disease are described below. Early studies of humanized mice helped to identify inflammatory pathways involved in the development of breast cancer5. However, improvements to relevant humanized mice have made it possible to study the more-complex interactions among myeloid cells, antigen-presenting cells and T cells, including regulatory T cells, in the reconstituted tumor microenvironment. Notably, such models have enabled the combination of patient-derived xenografts with engraftment of allogenic HSCs for study of the therapeutic potential of checkpoint inhibitors, alone or in combination with histone-deacetylase inhibitors, to reduce tumor regression. In addition, autologous models containing patient-derived xenografts and autologous immune cells can be used to test the efficacy of various immunotherapies directed against a patient’s own tumor and to predict effective treatments6.

Humanized mice offer the ability to investigate mechanisms of therapeutic effector function in vivo6 and are used to define mechanisms associated with immunotherapy toxicity that include the development of autoimmune antibodies. For example, treatment of leukemia-bearing humanized mice with chimeric antigen receptor T cells has demonstrated a key role for monocytes in producing IL-1 and IL-6 during cytokine-release syndrome7. Blocking the IL-6 receptor or the IL-1 receptor controls the signs and symptoms of cytokine-release syndrome or neurotoxicity, respectively7. Thus, humanized mice have contributed substantially to the improvement of anti-cancer therapies.

Transplantation of non-self (‘allogeneic’ or ‘xenogeneic’) cells and tissues stimulates a robust host immune response that mediates allograft rejection. Traditional immunocompetent mouse models are effective tools with which to analyze immune responses directed against engrafted allogeneic tissues, including PBMCs, human T cell subsets and human CD34+ HSCs. Humanized mice also have enabled the direct study of human tissue rejection mediated by human immune cells and the testing of novel therapeutic strategies to prevent rejection8. HIS mice have been used to investigate the immunological rejection of human skin, pancreatic islets, cardiac tissues, pluripotent stem cell–derived populations, and xenografts. They also have facilitated the evaluation of human-specific therapeutics that suppress immune-system-mediated rejection of allografts, including CTLA4–Ig and monoclonal antibodies targeting CD3, CD28, CD154, 4–1BB, ICOS ligand and OX40 ligand. Moreover, such models have enabled the testing of human regulatory T cell and mesenchymal stem cell therapies to prevent human allograft rejection, which has provided insights into T cell effector mechanisms essential for rejection. Overall, HIS mouse models have become an essential tool for human transplantation biology for the testing of innovative approaches to prolong allograft survival.

As autoimmunity is a complex process that involves multiple cell types and genetic loci, the development of an animal model capable of recapitulating human autoimmune disease requires the establishment of a sophisticated human immune system in the mouse host. Early studies using SCID mice given injection of PBMCs from autoimmune patients demonstrated the occasional development of autoantibodies and engraftment of functional autoreactive T cells. Although poor B cell maturation in most humanized mouse models has limited the study of peripheral B cell tolerance, improved HIS mouse models given transplantation of human HSCs have enabled investigations into mechanisms of central lymphoid tolerance, including receptor editing and clonal deletion9. Humanized mice also support the establishment of key features of pristane-induced systemic lupus erythematosus, such as increased production of anti-nuclear autoantibodies and pro-inflammatory cytokines, as well as multi-organ and fatal autoimmunity caused by defective transcription factor FOXP310. The use of more-advanced immunocompetent BLT humanized mice, in which human T cells become educated on human HLAs, has facilitated the study of autoimmunity. For example, BLT humanized mice given adoptive transfer of human CD4+ T cells reactive to an insulin B-chain peptide develop insulitis and diabetes11. Therefore, various HIS mouse models exhibit key aspects of human autoimmunity that will be necessary for the development of novel therapeutics.

Humanized mouse models are perhaps most useful for the study of HIV, as they mimic human HIV infections with high levels of viremia and depletion of CD4+ T cells and also support the establishment of a persistent latent virus reservoir. BLT humanized mouse models enable the study of the physiologically relevant mucosal (intravaginal and intrarectal) and oral routes of HIV transmission as well as of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) to prevent transmission12. Some BLT models expressing distinct HLA haplotypes develop human HIV-specific T cell responses capable of selecting for viral escape mutations13. A humanized triple-knockout BLT mouse model lacking the RAG-2 recombinase component, the γ-chain of the IL-2 receptor and the signal-regulatory protein CD47 (Rag2−/−Il2rg−/−Cd47−/− BLT mice) has supported the study of traditional small-molecule ART and non-traditional therapeutic approaches, such as treatment with interferon-α14. Humanized NSG mouse models have also been instrumental in explorations of the efficacy of gene-modified HSCs toward a functional cure for HIV, including zinc-finger-mediated disruption of the HIV co-receptor CCR515 and the production of HIV-specific T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors15. Subsequently, HIS (NRG-hu Liv/Thy) mice served as an effective small-animal model with which to study combined approaches using vaccination and latency-reversing agents15, as well as broadly neutralizing antibodies15, to limit the HIV reservoir.

The lack of small-animal models with which to investigate liver disease induced by hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) has impeded delineation of the virological and immunological mechanisms of viral persistence and efficient testing of new therapeutics. Humanized mouse models engrafted with human immune cells, human hepatocytes and hepatic stellate cells have been developed that support infection with HBV or HCV and the subsequent immunopathogenesis. When infected with HBV, such engrafted mice mount virus-specific immune responses and develop histopathological features reminiscent of human liver disease associated with pathogenic M2-like macrophages16. The low level of human hepatocyte development from fetal hepatocytes and low HBV replication have been improved through engraftment of adult hepatocytes and allogeneic human fetal HSCs17.

Humanized mice are useful for the investigation of other viruses beyond HIV, HBV and HCV18. Humanized mice infected with the herpesvirus Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) enable modeling of B cell lymphoproliferative disease and EBV-driven lymphoma formation. Clinical features of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and erosive arthritis associated with EBV infection also can be recapitulated in humanized mice, which has led to the investigation of therapies for these conditions. Human cytomegalovirus, another herpesvirus, can establish latent infection in humanized mice in a way similar to its establishment in humans, including reactivation after treatment with G-CSF, which has enabled the study of this virus and its control with antiviral agents. Additionally, Dengue virus, a mosquito-borne flavivirus, can successfully infect humanized mice and establish clinical signs such as fever and erythema. Dengue virus–infected mosquitoes can model transmission via bite in humanized mice, which results in higher viremia and a severe form of the disease19. Humanized mice also are capable of supporting infection with Zika virus and developing Zika virus–specific antibody responses, which has provided a model with which to test antiviral therapeutics20. Therefore, humanized mouse are capable of supporting infection with and immunity to various human viruses, which facilitates the testing of therapeutic interventions.

While parasitic and bacterial pathogens are generally less host specific than are viruses, humanized mice have proven useful for studies of certain microbes, particularly when human hematopoietic and immune cells exert a strong influence on their pathogenesis. Similarly, humanized mice support infection with Neisseria meningitidis and develop vascular damage18, including the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines that leads to neutrophil infiltration and inflammation and results in skin-graft pathology. Several groups have also used humanized mouse models to study infection with Salmonella typhi and dissemination of this bacteria to multiple organs18. Humanized mice also support infection with and immunity to Leishmania major, Borrelia hermsii and some strains of Streptococcus18. Thus, humanized mice also aid in understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of human bacterial and parasitic infections.

Challenges, alternatives and strategies

Humanized mouse models, generated with either fetal human tissues or non-fetal human tissues, have dramatically improved the ability to study human diseases. However, discussions at the meeting made it clear that no single model is sufficient to support the broad array of research areas described above. Many of these models also have numerous limitations, including the potential for xeno-reactive graft-versus-host disease and its ensuing complications; limited lifespan; incomplete human immune function, including a lack of B cell immunoglobulin G responses; low levels of human-cell reconstitution of gut-associated lymphoid tissues; and underdeveloped lymphoid organs and poorly developed lymphoid architecture. These issues need to be carefully considered in the interpretation of experimental results. Fetal tissue–based BLT humanized mice pose additional practical limitations that include the following: access to adequate amounts of tissue; tissue collection and storage requirements; reproducibility; and broad availability to the research community. Nonetheless, the availability of a small-animal model greatly facilitates the conduct of rapid, iterative studies.

Humanized mice generated from non-fetal cells and tissues (for example, neonatal or adult stem cells, or umbilical cord blood) have been used for specific indications. These newer models need further development, as they currently do not recapitulate the immune-system functionality observed in fetal tissue–based BLT humanized mice. Careful head-to-head (direct) comparisons of humanized mice constructed with HSCs and different sources of human tissues are needed for better understanding of the potential of the various model systems to recapitulate critical human immune responses across an array of human diseases.

Conclusions and next steps

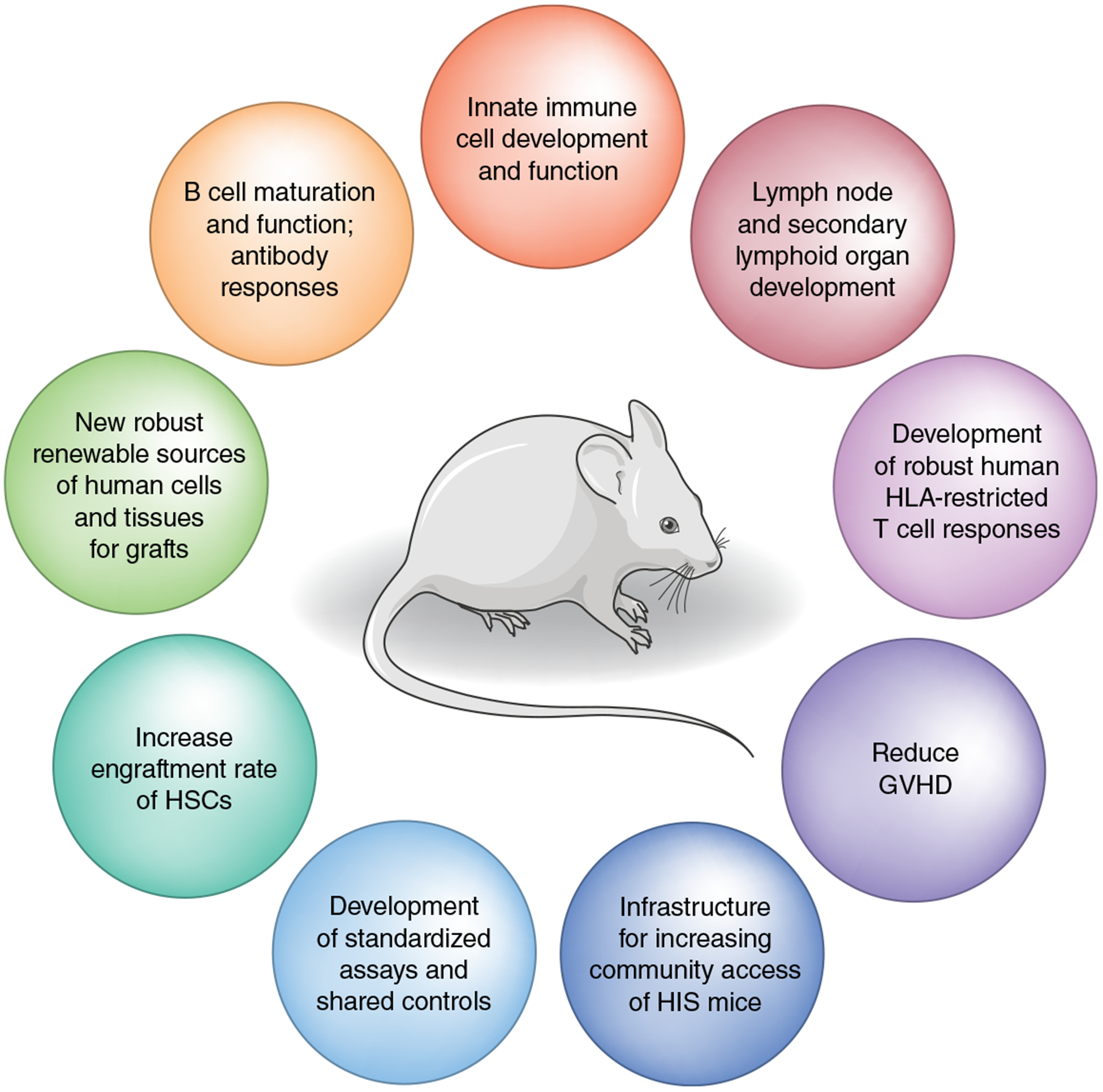

Humanized mice have become an important tool for many research applications, including human immune function, infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases, cancer, and organ or tissue transplantation. In addition to the need for direct comparisons of humanized mice generated with fetal tissue and those generated with non-fetal tissue, improving current HIS mouse models to better recapitulate the human immune system has the potential to lead to new biological insights and permit the assessment of new biological therapies (Fig. 2). The US National Institutes of Health is committed to supporting studies that develop humanized mouse models that do not rely on human fetal tissue and faithfully represent the human immune system (as indicated in the notices NOT-AI-19–040 and NOT-OD-19–042 and an announcement of concept clearance (https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/january-2019-dait-council-approved-concepts#07)).

Fig. 2 |. Areas that require development and optimization in HIS mice.

Areas in the field that need more development and study of humanized mice that better recapitulate and/or reflect human immune responses; these can be used for better understanding of infectious disease, autoimmunity and cancer development and for the evaluation of therapies. GVHD, graft-versus-host disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Abraham, A. Augustine and J. Breen for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.McCune JM et al. Science 241, 1632–1639 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suntharalingam G et al. N. Engl. J. Med 355, 1018–1028 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shultz LD et al. Mamm. Genome 10.1007/s00335-019-09796-2 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rongvaux A et al. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 364–372 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pedroza-Gonzalez A et al. J. Exp. Med 208, 479–490 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wege AK BioDrugs 32, 245–266 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norelli M et al. Nat. Med 24, 739–748 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenney LL, Shultz LD, Greiner DL & Brehm MA Am. J. Transplant 16, 389–397 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lang J et al. J. Exp. Med 213, 93–108 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goettel JA et al. Blood 125, 3886–3895 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tan S et al. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 10954–10959 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Victor Garcia J Curr. Opin. Virol 19, 56–64 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudek TE et al. Sci. Transl. Med 4, 143ra98 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lavender KJ et al. AIDS 32, 1–10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carrillo MA, Zhen A & Kitchen SG Front. Immunol 9, 746 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng L, Li F, Bility MT, Murphy CM & Su L Antiviral Res. 121, 1–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dusséaux M et al. Gastroenterology 153, 1647–1661.e9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ernst W Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis 49, 29–38 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cox J, Mota J, Sukupolvi-Petty S, Diamond MS & Rico-Hesse RJ Virol. 86, 7637–7649 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitt K et al. Virology 515, 235–242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schultz L et al. Nat. Rev. Immunol 12, 786–242 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]