Abstract

Background:

Palliative care improves quality of life in patients with heart failure (HF). Whether men and women with HF derive similar benefit from palliative care interventions remains unknown.

Methods:

In a secondary analysis of the PAL-HF trial, we analyzed differences in quality of life among men and women with HF and assessed for differential effects of the palliative care intervention by sex. Differences in clinical characteristics and quality of life metrics were compared between men and women at serial time points. The primary outcome was change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) score between baseline and 24 weeks.

Results:

Among the 71 women and 79 men, there was a significant difference in baseline KCCQ (24.5 v. 36.2, respectively, p=0.04) but not FACIT-PAL (115.7 v. 120.3, p=0.27) scores. Among those who received the palliative care intervention (33 women, 42 men), womens’ quality of life score remained lower than mens’ after enrollment. Treated mens’ scores were significantly higher than those untreated (6 Month KCCQ 68.0 (IQR 52.6 – 85.7) v. 41.1(IQR 32.0 – 78.3; P=0.047) while the difference between treated and untreated women was not significantly different (p=0.39) Rates of death and rehospitalization as well as the composite endpoint were similar between treated and untreated women and men.

Conclusions:

In the PAL-HF trial, women with HF experienced a greater symptom burden and poorer quality of life as compared to men. The change in treated men’s KCCQ between baseline and 24 weeks was significantly higher than those untreated; this trend was not observed in women. Thus, there may be a sex disparity in response to palliative care intervention, suggesting that sex-specific approaches to palliative care may be needed to improve outcomes.

Registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov; Unique Identifier: NCT01589601

Despite ongoing advancements in medical and device therapy, heart failure (HF) affects over 5 million people in the United States and remains a significant global health burden1. As the disease progresses, patients experience an increase in symptom burden and a decrease in quality of life2. This appears to be particularly true for women, who experience higher rates of death and HF hospitalizations than men3. When compared to men, women with HF are more likely to be older, have a history of hypertension and diabetes, and have heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF)4. Importantly, women also experience significantly higher rates of comorbid depression and anxiety, and may cope with their disease more poorly5.

The beneficial role of palliative care - a multidisciplinary approach focused on quality of life and symptom management – has become increasingly recognized in the heart failure population6. Recently, the Palliative Care in Heart Failure (PAL-HF) trial demonstrated an improvement in quality of life, anxiety, depression, and overall well-being measures with an interdisciplinary palliative care intervention compared with usual medical care (UC) in patients with advanced HF7. While the benefits of palliative care in advanced HF are increasingly recognized, limited data are available regarding response to this intervention by sex. Thus, using data from the PAL-HF trial we sought to: 1) identify differences in baseline clinical characteristics and quality of life metrics between men and women; 2) estimate the differential effects of palliative care treatment on patient-reported quality of life between sexes; and 3) assess differences in cumulative incidence of death and rehospitalization for HF by sex and treatment strategy.

Methods

Study Design

The design of the PAL-HF trial has been published previously8. In brief, patients with advanced HF were randomized in a 1:1 manner to UC alone or UC plus a palliative care intervention, with patients followed until death or study conclusion at 24 weeks. Patients in the treatment arm received assessment and management of multiple domains of quality of life including physical symptoms, psychosocial and spiritual distress, and advanced care planning by a palliative care nurse practitioner and board certified palliative care physician in combination with evidenced-based treatment by the patient’s primary care and/or cardiology team. Enrolled patients were admitted with or recently discharged from (<2 weeks) an acute HF hospitalization and were at high risk for mortality or rehospitalization based upon their Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness risk score9. Exclusion criteria included anticipation of heart transplantation or ventricular assist device placement within 6 months as well as non-cardiac terminal illness8. In the PAL-HF trial, change in quality of life was the primary endpoint, as assessed by the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Palliative Care scale (FACIT-Pal)10, 11. The KCCQ is a 23-item disease-specific questionnaire that quantifies physical function, frequency and severity of symptoms, and quality of life in a score between 0 and 100. Similarly, the FACIT-PAL is a 46-item self-reported measure of health-related quality of life which generates a score of 0 to 184. In both metrics, higher scores indicate better health status. The study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained. Because of the sensitive nature of the data collected for this study, requests to access the dataset from qualified researchers trained in human subject confidentiality protocols may be sent to the Duke Clinical Research Institute.

Outcomes

In the current analysis, differences in baseline demographics, past medical history, relevant laboratory values, and medications were first compared between men and women enrolled in the trial. Data on quality of life metrics were then compared between men and women in the treatment arm at baseline and at serial time points (6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks). A linear mixed model was generated for KCCQ and FACIT-PAL scores taking into account longitudinal data and the correlations between baseline and follow-up responses for each patient. In addition, median scores were compared between treated and untreated patients of each sex cross-sectionally at serial time points. The primary endpoint for the present analysis was change in KCCQ score between baseline and 24 weeks. Despite no significant difference in clinical outcomes between treatment groups in the original trial, the secondary endpoint of interest in exploratory analysis was the composite endpoint of 6-month mortality or heart failure rehospitalization.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are described as the mean, standard deviation, median, 25th and 75th percentiles, minimum and maximum. Discrete factors are presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical comparisons were generated using the Fisher’s Exact or the Chi-Square test for discrete factors and the Wilcoxon Rank Sum for continuous measures. The ANOVA multiple comparisons method was utilized for repeated measures. Linear mixed models were generated to assess the association between sex and KCCQ or FACIT PAL score. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed for the endpoint of 6 month mortality or heart failure hospitalization. All modeling assumptions were verified. Transformations were not required. The multivariate model included age and heart failure phenotype [i.e., heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) vs. HFpEF]. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Because of the small sample size and hypothesis-generating nature of the present study, interaction terms were tested, but exploratory analysis was performed regardless of statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, North Carolina) verison 9.4.

Results

Study Population

A total of 150 patients were included in the PAL-HF trial, among whom 71 (47%) were women and 79 (53%) were men. A total of 33 women (47%) and 42 men (53%) received the palliative care intervention. Between men and women, there was no statistically significant difference in age or race (Table 1). A smaller proportion of women had coronary artery disease and ischemic cardiomyopathy with a trend toward a shorter duration of HF. More women had HFpEF. There were no differences in the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, and pulmonary disease, although depression treated with medication was significantly different between the groups.

Table 1 –

Sex-Specific Differences in Baseline Characteristics

| Demographics and Clinical | Female (N=71) |

Male (N=79) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 72.0 (59.0, 81.0) [71] | 73.0 (65.0, 80.0) [79] | 0.38 |

| Randomized Treatment | 0.41 | ||

| Usual Care | 38(53.5%) | 37(46.8%) | |

| Usual + Intervention | 33(46.5%) | 42(53.2%) | |

| Race | 0.23 | ||

| African American/Black | 34(47.9%) | 28(35.4%) | |

| Caucasian/White | 36(50.7%) | 50(63.3%) | |

| Asian | 1(1.4%) | 1(1.3%) | |

| Etiology: Ischemic HF | 26(38.8%) | 46(61.3%) | 0.01 |

| New York Heart Class III/IV | 65(92.9%) | 67(85.9%) | 0.17 |

| Baseline EF > 55% (Normal) | 24(33.8%) | 11(13.9%) | 0.01 |

| Duration of HF (months) Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 30.0 (10.0, 88.0) [71] | 59.0 (15.0, 113.0) [79] | 0.09 |

| Hypertension | 57(80.3%) | 56(71.8%) | 0.23 |

| Diabetes | 43(60.6%) | 37(47.4%) | 0.11 |

| Stroke | 12(16.9%) | 16(20.5%) | 0.57 |

| COPD | 18(25.4%) | 23(29.5%) | 0.57 |

| Depression Treated with Medication | 17(23.9%) | 8(10.4%) | 0.03 |

| Hemodynamics and Lab Values | |||

| Peripheral edema | 0.09 | ||

| None | 22(31.4%) | 27(34.6%) | |

| Trace | 30(42.9%) | 26(33.3%) | |

| Moderate | 18(25.7%) | 19(24.4%) | |

| Severe | 0(0.0%) | 6(7.7%) | |

| Creatinine Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 1.5 (1.2, 2.0) [69] | 1.9 (1.3, 2.3) [78] | 0.07 |

| Total Bilirubin Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 1.0 (0.7, 1.6) [23] | 1.0 (0.9, 2.0) [23] | 0.25 |

| Albumin Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 3.0 (2.9, 3.4) [27] | 3.0 (2.9, 3.3) [25] | 0.63 |

| Pro-BNP | 8520 (4361, 17680) [60] | 6930 (4285, 11594) [66] | 0.39 |

| Medications | |||

| Ace/ ARB | 25(35.2%) | 19(24.1%) | 0.13 |

| Beta Blocker | 47(66.2%) | 52(65.8%) | 0.96 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 23(32.4%) | 29(36.7%) | 0.58 |

| Prior Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillator (ICD) / Pacemaker Implantation | 26(37.1%) | 43(55.8%) | 0.02 |

| Baseline Quality of Life Metrics | |||

| KCCQ Score Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 24.5 (17.4, 42.2) [71] | 36.2 (22.9, 47.0) [76] | 0.04 |

| FACIT-PAL Median (25th, 75th) [N] | 115.7 (97.2, 135.0) [71] | 120.3 (105.0, 137.0) [77] | 0.27 |

| Spending more than half of the time in bed | 49(70.0%) | 41(54.7%) | 0.06 |

| Religion is deeply important | 55(78.6%) | 48(63.2%) | 0.04 |

| Has a Living Will | 10(37.0%) | 21(63.6%) | 0.04 |

| Marital Status | <0.01 | ||

| Never Married | 7(9.9%) | 3(3.8%) | |

| Married/living as married | 20(28.2%) | 49(62.8%) | |

| Divorced/separated | 13(18.3%) | 16(20.5%) | |

| Widowed | 31(43.7%) | 10(12.8%) |

As compared to men, women had worse KCCQ (24.5 v. 36.2, p=0.04) and similar FACIT-PAL (115.7 v. 120.3, p=0.27) scores at baseline despite similar proportions of women and men with physician-assigned NYHA Class III or IV HF symptoms. Significantly more women were treated with medication for depression and 70% of women reported spending over half of their time in bed. Marital status differed significantly by sex, where 44% of women were widowed at the time of study enrollment as compared to 13% of men. Women were more likely to rely on family as their primary care givers (60%) as compared to men who were more likely to be cared for by self (39%) or family (39%).

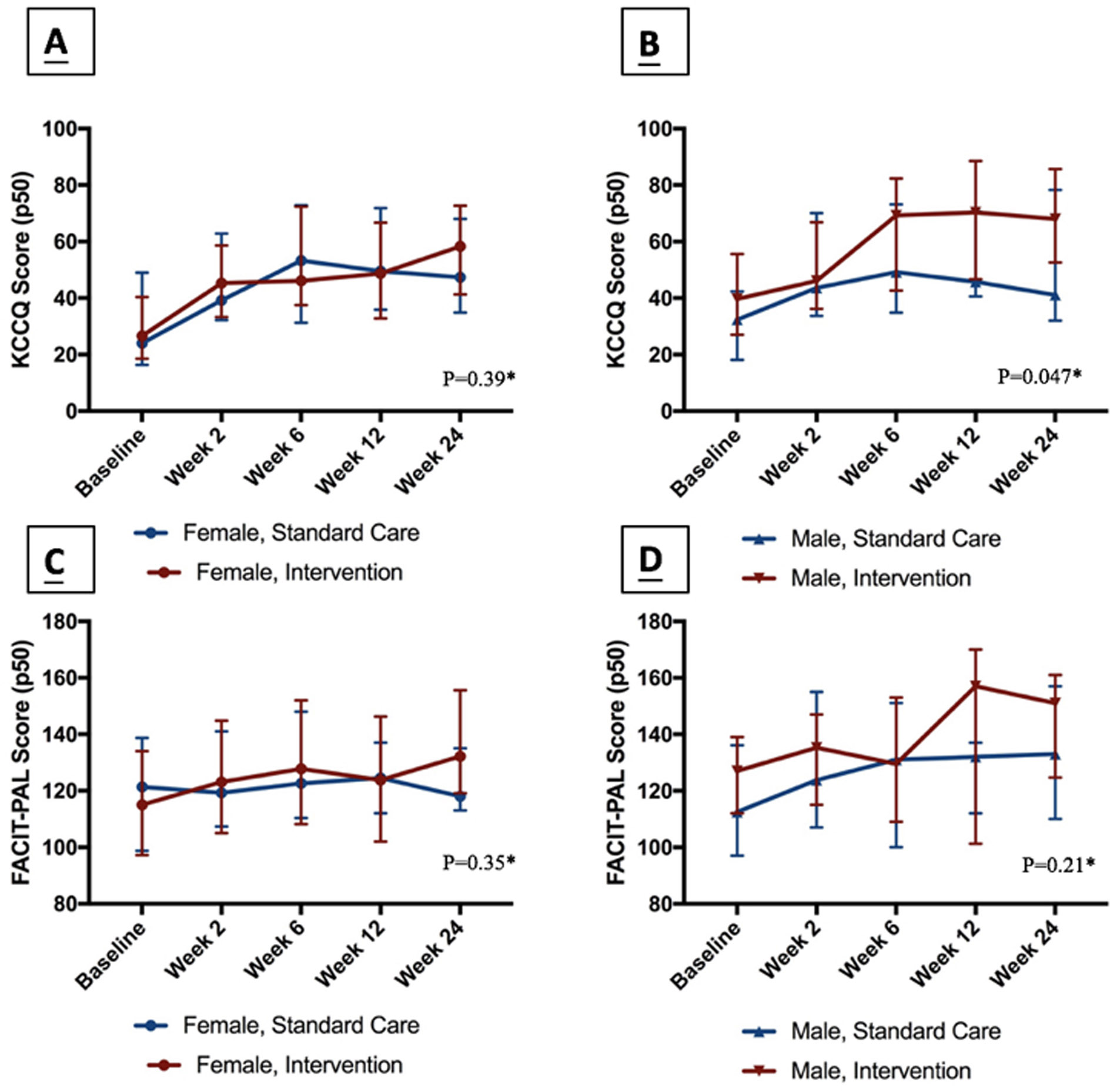

While least squared mean scores for both treated men and treated women increased in the early post-discharge period, womens’ quality of life scores remained lower than mens’ throughout the study period (Supplemental Table 1). The median 6-month KCCQ score was higher in treated v. untreated men (68.0 v. 41.1), and the difference between baseline and 6-month values trended was significant between treated and untreated men (p=0.047 but not in women (p=0.39) (Figure 1). The interaction term between sex, treatment, and time point were not statistically significant (p=0.86 for KCCQ score and p=0.35 for FACIT-PAL score).

Figure 1:

Trends in KCCQ and FACIT-PAL Scores From Baseline to Week 24. (A) Change between baseline and 24-week KCCQ score between treated and untreated women. (B) Change between baseline and 24-week KCCQ score between treated and untreated men. (C) Change between baseline and 24-week FACIT-PAL score between treated and untreated women. (D) change between baseline and 24-week FACIT-PAL score between treated and untreated men. *P-values correspond to the difference between treated and untreated patients in their score change from baseline to 24 weeks.

The incidence rate of 6-month mortality or rehospitalization was 55% in untreated women and 57% in treated women compared to 58% and 50% in untreated and treated men, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant even after adjusting for age and heart failure phenotype [adjusted HR 1.10 95% CI (0.70, 1.75), p=0.21] (Supplemental Table 2).

Discussion:

The current study examines differences in quality of life among men and women living with advanced heart failure and the impact of a palliative care intervention on outcomes including KCCQ score, FACIT-Pal score, and cumulative incidence of mortality and heart failure rehospitalization. Important findings include 1) at baseline, women with advanced heart failure experienced increased symptom burden and poorer quality of life as compared to men, 2) there was no significant treatment effect within or between genders, though the change in mens’ KCCQ scores between treated and untreated patients from baseline to 24-weeks was significant and 3) the cumulative incidence of mortality and heart failure hospitalization were similar in women and men regardless of treatment. Taken together, our findings suggest the possibility that approaches to quality of life improvement and symptom management may need to be sex-specific in order to improve the disparity between women and men living with advanced heart failure.

Previous studies have suggested that despite optimal medical therapy, women experience a greater burden of heart failure symptoms and poorer quality of life than their male counterparts12. In a secondary analysis of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and Morbidity (CHARM) study, for example, women were found to have increased self-reported symptoms including dyspnea at rest and with exertion as well as dependent edema13. The current study supports these previous findings suggesting that women with heart failure experience greater symptom burden, more peripheral edema, and significantly lower baseline quality of life metrics including KCCQ and FACIT-Pal scores. Interestingly, these patient-reported outcomes differ from physician-assigned New York Heart Association symptom classification, where a similarly proportion of men and women were classified as Class III or IV. These differences also occurred on a background of similar goal-directed medical therapy, though not adjusted for heart failure phenotype in the setting of the modest sample size of PAL-HF. Other potential contributions to the disparity in baseline quality of life between men and women identified in this study include comorbid depression, widower status, and increased reliance on family as caregivers, all of which were significantly more prevalent in women in this cohort. Taken together these findings suggest that women living with advanced heart failure experience greater symptom burden, psychological distress, and impairment in functional status which may not be reflected in physician-reported outcomes. Additional attention to comorbid depression and anxiety and social support systems may be a key to improving quality of life in women with advanced heart failure.

Our analysis has several important limitations. First, our overall sample size was small, and we are likely underpowered to detect significant differences when accounting for both sex and treatment arm. This may have also resulted in the inability to detect significant interactions between sex and treatment over serial time points. In addition, the single-center nature of our study potentially limits its generalizability, particularly because the intervention was conducted by a single, female nurse practitioner, which may have influenced patient perceptions and patient response to treatment due to interpersonal factors that are difficult to quantify. Additionally, the influence of heart failure phenotype (preserved versus reduced ejection fraction) must be taken into account, as lack of proven therapies to improve outcomes in end-stage diastolic heart failure may confound outcomes. Lastly, as previously reported in the PAL-HF trial, 12% of patients were lost to follow up during the study period, contributing to missing data for the primary and secondary endpoints.

In conclusion, women living with advanced heart failure experience a greater symptom burden and poorer quality of life as compared to men. Though it did not meet statistical significance, there may be a sex disparity in response to palliative care intervention, with women deriving less benefit than men from interventions intended to improve patient-reported outcomes. Additional research into sex-specific approaches to quality of life assessment and palliative care interventions are likely needed to improve quality of life in women living with advanced heart failure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: None

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Savarese G and Lund LH. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3:7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan RF, Feder S, Goldstein NE and Chaudhry SI. Symptom Burden Among Patients Who Were Hospitalized for Heart Failure. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1713–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun LY, Tu JV, Coutinho T, Turek M, Rubens FD, McDonnell L, Tulloch H, Eddeen AB and Mielniczuk LM. Sex differences in outcomes of heart failure in an ambulatory, population-based cohort from 2009 to 2013. CMAJ. 2018;190:E848–E854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenchaiah S and Vasan RS. Heart Failure in Women--Insights from the Framingham Heart Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29:377–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopper I, Kotecha D, Chin KL, Mentz RJ and von Lueder TG. Comorbidities in Heart Failure: Are There Gender Differences? Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2016;13:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warraich HJ and Rogers JG. It Is Time to Discuss Dying. JACC Heart failure. 2018;6:790–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, Adams PA, Speck A, Johnson KS, Krishnamoorthy A, Yang H, Anstrom KJ, Dodson GC, Taylor DH Jr., Kirchner JL, Mark DB, O'Connor CM and Tulsky JA. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: The PAL-HF Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2017;70:331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mentz RJ, Tulsky JA, Granger BB, Anstrom KJ, Adams PA, Dodson GC, Fiuzat M, Johnson KS, Patel CB, Steinhauser KE, Taylor DH Jr., O'Connor CM and Rogers JG. The palliative care in heart failure trial: rationale and design. American heart journal. 2014;168:645–651 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Connor CM, Hasselblad V, Mehta RH, Tasissa G, Califf RM, Fiuzat M, Rogers JG, Leier CV and Stevenson LW. Triage after hospitalization with advanced heart failure: the ESCAPE (Evaluation Study of Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Artery Catheterization Effectiveness) risk model and discharge score. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010;55:872–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR and Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;35:1245–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons KD, Bakitas M, Hegel MT, Hanscom B, Hull J and Ahles TA. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Palliative care (FACIT-Pal) scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37:23–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK and Tennstedt SL. Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Meara E, Clayton T, McEntegart MB, McMurray JJ, Pina IL, Granger CB, Ostergren J, Michelson EL, Solomon SD, Pocock S, Yusuf S, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA and Investigators C. Sex differences in clinical characteristics and prognosis in a broad spectrum of patients with heart failure: results of the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) program. Circulation. 2007;115:3111–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.