In terms of mitigating the health-related impacts of disasters, pharmacists are the unsung heroes. Without them, there would be no medications for patients in need during and following a disaster or emergency. These days, pharmacists offer more than just logistics and dispensing during emergencies, which parallels the evolution of the profession.

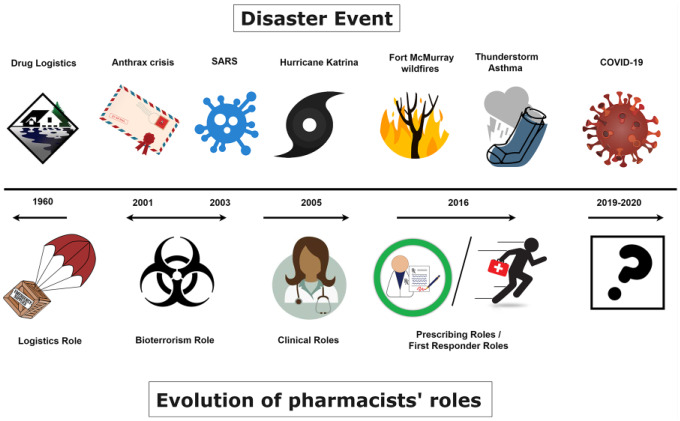

Pharmacists have always been assisting in emergencies but previously have rarely been recognized for their contributions. Before 2001, pharmacists were only acknowledged for their primary role in logistics—getting drugs to where they were needed in an emergency.1,2 Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of pharmacists’ roles in disasters as outlined in the literature.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the evolution of pharmacists’ roles in disasters since 1960

Key points/recommendations.

Although logistics are important, pharmacists are qualified clinicians in disasters and emergencies.

Pharmacists should be recognized for the utilization of their full scope of practice (including patient assessment and prescribing) in a disaster or emergency.

In emergency situations, pharmacists have demonstrated that they have an integral role in the emergency health response and recovery from disasters.

Pharmacists need to be included in disaster planning and preparedness for there to be an appropriate health response in an emergency.

Pharmacists cannot rely solely on large-scale disaster events to propel the advancement of their scope of practice.

Pharmacy leadership should seek opportunities to offer and advocate for the full utilization of pharmacists’ services.

In 2001, following the terrorist attacks and anthrax scares in the United States, pharmacists were identified as being invaluable during bioterrorism threats in providing their expertise (screening and treating).3-11

In 2003, the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Canada saw pharmacists becoming an essential information source for community members and patients.12,13

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina saw pharmacists’ scope of practice being temporarily extended to include prescribing of 30-day emergency medication supplies and using other clinical skills that were needed in the absence of other health care providers.14-16

In 2016, in Australia, the Thunderstorm Asthma event acknowledged that pharmacists were an integral part of the emergency response and identified that public health care services needed to learn how to work with pharmacists and the primary health care sector.17

Between 2009 and 2016 in Canada, there were several events that saw pharmacists being progressively more sought after for their expertise in assessing and prescribing—the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza,18 the 2011 Slave Lake wildfires, the 2013 Calgary floods19 and the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfires.20

What is apparent is that the pharmacist’s role has evolved from logistics and drug supply to now include assessment and prescribing roles. During the Calgary floods and Fort McMurray wildfires, pharmacists were increasingly being sought after for their clinical expertise.20 In the case of Fort McMurray, the Alberta Health Services’ pharmacy leadership made the suggestion to their upper management for the utilization of pharmacist assessing and prescribing services (D. Van Haaften, personal communication, January 2020). Patients were being evacuated without their identification, money or medications, and pharmacists were requested to set up a medical area within the evacuation centers to provide a health care service to the displaced community. They assessed patients and prescribed medications—they did not fill prescriptions. Shortly thereafter, pharmacists were requested to join the field hospital set up by the military and asked to assess and triage patients. It was not only the displaced and disaster-affected individuals that pharmacists helped but also the volunteer firefighters who suffered from smoke inhalation or ran out of their medications.

Perhaps disasters are the stepping stone for the advancement to a full scope of practice for pharmacists within a country. In 2019, Watson et al.21 compared different countries’ disaster pharmacy legislation, which revealed a correlation between the number of disasters experienced by a specific country’s jurisdiction and the presence of disaster-specific pharmacy legislation (e.g., emergency supplies, vaccinations and pharmacy relocation). It is also possible that the study of pharmacists’ responses during times of crises can provide insights into their adoption of a full scope of practice.

In 2018, an international Delphi study conducted with key stakeholders in disaster health and/or pharmacy identified 43 roles that pharmacists should be undertaking in a disaster.22 The study also states that greater awareness by the general public and other health care professionals is needed to further this advancement of pharmacists’ roles during disasters.22 It is imperative that pharmacy organizations advocate for these pharmacists’ roles and publicize the message that pharmacists are an essential service in emergencies. This message is important in order for the disaster health community to recognize pharmacists’ contributions but also for pharmacists to understand their vital role as first responders in the community. Pharmacy organizations need to step up and advocate for the full utilization of pharmacists’ services. They are also responsible for providing support and ongoing training opportunities for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce to be prepared for disasters and emergencies.22

One might suggest that these crises brought out the best in pharmacists and the best in pharmacy practice. They allowed us to show what we are capable of. Currently in Canada, many changes to scope of pharmacy practice have been made as a result of COVID-19. In Alberta, pharmacists have received access to a billing code that allows them to be reimbursed for assessing and screening potential COVID-19 patients.23 In British Columbia, pharmacists have been empowered to assess and prescribe emergency supplies of patients’ chronic disease medications and given refill authorization in an effort to decrease the burden on the health care system.24,25 These enhanced emergency supply provisions have been echoed in Australia, with some states extending the disaster emergency supply arrangements during the pandemic.26 We expect that the COVID-19 pandemic now upon us will demonstrate the value of pharmacists’ roles in disasters even further.

References

- 1. Ford H, Dallas CE, Harris C. Examining roles pharmacists assume in disasters: a content analytic approach. Disaster Med Public Health Preparedness 2013;7(6):563-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berod T, Chan-ou-Teung F. Pharmacist’s role in rescue efforts after plane crash in Indian Ocean. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1997;54(9):1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Setlak P. Bioterrorism preparedness and response: emerging role for health-system pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004;61(11):1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Babb J, Downs K. Fighting back: pharmacists’ roles in the federal response to the September 11 attacks. J Am Pharm Assoc 2001;41(6):834-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen V. Organization of a Health-System Pharmacy Team to Respond to Episodes of Terrorism. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2003;60(12):1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee JJ, Johnson SJ, Sohmer MJ. Guide for mass prophylaxis of hospital employees in preparation for a bioterrorist attack. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66(6):570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Haffer A, Rogers J, Montello MJ, Frank EC, Ostroff C. 2001 Anthrax crisis in Washington, DC: pharmacists’ role in screening patients and selecting prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2002;59(12):1193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Terriff CM, Tee AM. Citywide pharmaceutical preparation for bioterrorism. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2001;58(3):233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ford H, von Waldner T, Perri M. Pharmacists’ roles in post-September 11th disasters: a content analysis of pharmacy literature. J Pharm Pract 2014;27(4):350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Feret B, Bratberg J, Cordy C, Mihalakos A, Low G, Kogut S. Establishment of a pharmacist consulting team for statewide bioterrorism preparedness. Prehosp Disaster Med 2005;20(Suppl 3):s161. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Feret B, Bratberg JP. A ten-year experience of a pharmacist consulting team for statewide bioterrorism and emergency preparedness. Med Health R I 2012;95(9):279-80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chin TWF, Chant C, Tanzini R, Wells J. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): the pharmacist’s role. Pharmacotherapy 2004;24(6):705-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Austin Z, Martin JC, Gregory PA. Pharmacy practice in times of civil crisis: the experience of SARS and “The Blackout” in Ontario, Canada. Res Soc Admin Pharm 2007;3(3):320-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hogue MD, Hogue HB, Lander RD, Avent K, Fleenor M. The non traditional role of pharmacists after Hurricane Katrina: process description and lessons learned. Public Health Rep 2009;124(2):217-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young D. Pharmacists play vital roles in Katrina response: more disaster-response participation urged. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2005;62(21):2202-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Velazquez L, Dallas S, Rose L, et al. A PHS pharmacist team’s response to Hurricane Katrina. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2006;63(14):1332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inspector-General for Emergency Management (IGEM), Victorian Government. Review of response to the Thunderstorm Asthma Event of 21–22 November 2016: final report. 2017. Available: https://www.igem.vic.gov.au/sites/default/files/embridge_cache/emshare/original/public/2017/07/80/c414fe2ba/ReviewofemergencyresponsetoNovember2016thunderstormasthmaeventfinalreport.pdf (accessed Mar. 13, 2020).

- 18. Chubaty A, Rowntree K, Chan A. Provision of pharmacy services at an influenza assessment centre. Can J Hosp Pharm 2011;64(1):48-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Epp DA, Tanno Y, Brown A, Brown B. Pharmacists’ reactions to natural disasters: from Japan to Canada. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2016;149(4):204-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsuyuki RT. Pharmacists’ responses to natural disasters: insights into the soul of pharmacists and our role in society. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2016;149(4):188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Watson KE, Singleton JA, Tippett V, Nissen LM. Do disasters predict international pharmacy legislation? Aust Health Rev [epub ahead of print 5 Dec 2019]. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Watson KE, Singleton JA, Tippett V, Nissen LM. Defining pharmacists’ roles in disasters: a Delphi study. PLoS One 2019;14(12):e0227132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mertz E. Pharmacists get billing code to screen Albertans for COVID-19; asked to limit drug supplies. Global News 2020 March 19. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/6703187/pharmacists-screen-coronavirus-alberta-health-drug-supply/ (accessed Mar. 21, 2020).

- 24. College of Pharmacists of British Columbia. COVID-19 public information—prescription refills can be provided by a pharmacist. March 18, 2020. Available: https://www.bcpharmacists.org/news/covid-19-public-information-prescription-refills-can-be-provided-pharmacist (accessed Mar. 26, 2020).

- 25. Coronavirus outbreak: pharmacists can provide some medications. Global News Morning BC 2020 March 21. Available: https://globalnews.ca/video/6713210/covid-19-pharmacists-can-provide-some-medications (accessed Mar. 26, 2020).

- 26. Haggan M. The public are looking to pharmacy to stand up in this crisis. Aust J Pharm 2020 March 25. Available: https://ajp.com.au/news/the-public-are-looking-to-pharmacy-to-stand-up-in-this-crisis/?utm_source=AJP+Daily&utm_campaign=2b22723f87-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2020_03_25_05_58&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_cce9c58212-2b22723f87-110163121 (accessed Mar. 26, 2020).