Abstract

In the face of COVID-19 and necessary shifts in service delivery for behavior analysts, caregiver involvement in behavioral interventions will likely increase. Resources that caregivers can consume and implement independently are critical in helping them manage behavior in their homes. This article includes antecedent and consequent behavior-management strategies that correspond with provided written instructions and video tutorials designed for caregivers. The materials presented within this article were originally produced and found effective in aiding caregivers managing behavior in their homes within the Alabama foster care system. Although individuals within this system are at a higher risk of abuse and neglect and may engage in higher levels of aberrant behavior, we are distributing this document in hopes it will help behavior analysts working across a variety of populations as they navigate changes in service delivery and adopt resources for continued care and caregiver training.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40617-020-00436-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Behavioral interventions, Caregiver training, COVID-19, Foster care, Resources for caregivers

Professionals in the field of behavior analysis have long suggested family and caregiver involvement is an important component of effective intervention. Professionals recommend that practitioners give caregivers of clients diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder ample information and education to support their participation in their children’s services (National Research Council, 2001). Although these professionals do not suggest that caregivers be the sole intervention agents for their children, the current worldwide pandemic, the COVID-19 virus, has severely limited families’ access to in-person services.

As governments and health organizations mandate social distancing to prevent the virus’s spread, children are spending an increased number of hours at home, with only caregivers and family members to modify their maladaptive behavior or teach new skills. Behavior-analytic service modalities must change. There are several evidence-based behavioral procedures that may be helpful for caregivers to receive exposure to as soon as possible. These strategies may aid caregivers as they learn to manage households during the current pandemic, especially those with children who may be facing changes in behavioral services.

Additionally, measures to ensure social distancing, such as working from home and closing schools, are putting strains on children and the agencies whose function is to protect them. With families experiencing greater life and economic stressors and children spending significantly more time at home, children are at a greater risk for abuse and neglect (Duggan et al., 2004; Slack, Holl, McDaniel, Yoo, & Bolger, 2004). The same measures also distance at-risk children from common reporters of maltreatment (e.g., school personnel), resulting in fewer reports to child protective services during this time. Meanwhile, multiple states across the United States are reporting stress on child protective services and the foster care system in the wake of this pandemic, the very systems meant to protect children from abuse and neglect (Brindley, 2020; Knowles, 2020; Rae, 2020). Current and potential foster caregivers are unable to attend in-person training, and foster children may experience additional trauma due to frequent placement disruptions or their inability to communicate with biological family or friends (Fecteau, 2020).

Practitioners from the Alabama Psychiatric Medication Review Team (APMRT), a collaborative project between Auburn University and the Alabama Department of Human Resources, work with children in foster care and children at risk of being removed from their homes. The primary function of APMRT is to provide behavioral interventions for challenging behavior and reduce the use of unnecessary psychotropic medication with foster youths. Members of APMRT wrote the enclosed materials and supporting statements to inform the intervention recommendations given to foster caregivers and biological caregivers receiving behavioral services and to provide remote information to caregivers still on the wait list for in-person services. In the wake of COVID-19, most of these services are temporarily suspended. Therefore, the purpose of the current article is to disseminate this list of evidence-supported practices, a corresponding written guide on intervention recommendations, and instructional videos describing the interventions (see Appendix) as a resource for caregivers, social workers, or behavior analysts as they transition to remote, at-home service delivery.

Using and Interpreting the Materials

The written intervention guide and instructional video tutorials can be helpful tools during the COVID-19 pandemic because they were adapted specifically for remote caregiver training. The authors derived all strategies from published behavior-analytic research, organized them into four categories (see the following list), and present them here in easily consumable, second-person language. Each category of strategies is linked to a corresponding free-access online video tutorial that provides further explanation and practical examples of each strategy. In addition, each video tutorial includes a comprehension quiz, such that practitioners can assess caregivers’ understanding of the material. The authors provide separate sections of the written guide here (see the Appendix for the entire written guide in a printable format), with additional information practitioners can utilize in supporting these recommendations while training caregivers or informing other stakeholders.

- Supporting statements for “Strategies to Build a Positive Environment in Your Home” and “Strategies for Responding to Your Child’s Requests” include the following:

- Supporting statements for “How to Give Instructions: Short, Do, and Follow-Through” include:

- Delivering the direction less than 5 ft away from the child, requesting eye contact from the child prior to instruction delivery, using directive statements instead of questions, using descriptive wording to give the instruction, and allowing 5 s for the child to respond increases compliance (Speights Roberts et al., 2008; Stephenson & Hanley, 2010).

- Providing praise contingent on following directions can increase compliance (Speights Roberts et al., 2008).

- Supporting statement for “How to Handle Junky Behavior: Pivot and Praise”:

- Supporting statements for “How to Handle Major Problem Behaviors” include:

- Using extinction (withholding preferred items, activities, and extra attention) paired with prompting the child to appropriately communicate wants can decrease problem behavior in the future (Shukla & Albin, 1996).

- Keeping demands in place and following through can reduce escape-maintained behavior in the future (Tarbox et al., 2007).

The authors present all the previous sections in complete documents in the Appendix. For practitioners who decide to limit the number of strategies they provide to caregivers, the following is a list of strategies categorized by three problem behavior functions:

- Attention-maintained behavior

- Strategy 1 from “Strategies to Build a Positive Environment in Your Home”

- “How to Give Instructions: Short, Do, and Follow-Through”

- “How to Handle Junky Behavior: Pivot and Praise”

- Tangible-maintained behavior

- Strategy 3 from “Strategies to Build a Positive Environment in Your Home”

- “Strategies for Responding to Your Child’s Requests”

- “How to Give Instructions: Short, Do, and Follow-Through”

- “How to Handle Major Problem Behaviors”

- Escape-maintained behavior

- Strategy 2 from “Strategies to Build a Positive Environment in Your Home”

- “How to Give Instructions: Short, Do, and Follow-Through”

- “How to Handle Major Problem Behaviors”

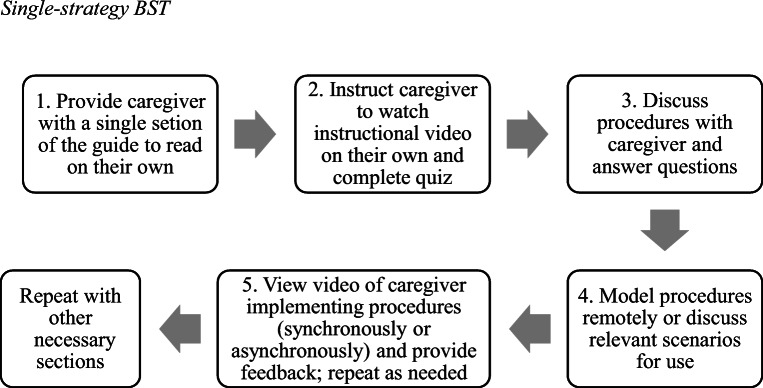

To aid in caregiver training using the materials provided within this article, the authors suggest practitioners follow or modify one of the flowcharts presented in Figs. 1, 2, and 3.

Fig. 1.

Modified behavioral skills training (BST) using all materials. The caregiver completes the instruction phase independently for all strategies. Practitioner involvement begins at Step 3, where supporting statements may be useful

Fig. 2.

Remote BST using all materials. Practitioner involvement begins at Step 1, where supporting statements may be useful. This training procedure includes a more resource-intensive instruction phase than that in Fig. 1

Fig. 3.

Single-strategy BST. The caregiver completes the instruction phase independently for one section of strategies. Practitioner involvement begins at Step 3, where supporting statements may be useful. This training procedure can be repeated for all relevant sections of the guide

Concluding Remarks

These strategies, in addition to training caregivers using BST, have proved useful for APMRT clinicians working with children of multiple ages and with different diagnoses inside foster and biological homes. These strategies and training procedures can readily be extended to other settings and contexts that behavior analysts are currently adapting to during this pandemic. APMRT clinicians often modify or add to the procedures in the Appendix, as needed, to meet the individual needs of clients and their households. Although the existing research and APMRT’s effective generalization of these procedures to a novel population suggest these procedures may be likely to work for most clients and families, the authors created the attached written guide and corresponding videos to serve as the instruction portion of BST, not for use as the sole intervention prescribed by behavior analysts.

The written guide includes brief recommendations in second-person language so professionals in the field may be able to distribute the document for caregivers to consume on their own. The online instructional videos provide further details and describe the written guide with some example scenarios. However, behavior analysts using these materials should ensure caregivers understand and can implement these procedures without causing harm to themselves or their children. Authors encourage caregivers who access these materials on their own to seek support from behavior-analytic professionals should they have any questions or concerns.

With the increase in the number of hours children are spending at home and the decreased availability of in-person services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, caregivers are becoming more responsible for managing behavior and teaching new skills in the home. Resources caregivers can access and consume independently are essential in continuing to provide behavior-analytic services. It is the authors’ hope that this review, and the tutorial materials contained within, may be helpful in aiding both caregivers and practitioners in this transition to at-home intervention.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(PDF 995 kb)

Funding

Portions of this article were supported by the Alabama Department of Human Resources, Family Services Division.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Brindley, E. (2020). Vulnerable children at greater risk of abuse, neglect as coronavirus isolates families. Retrieved from https://www.courant.com/coronavirus/hc-news-coronavirus-child-abuse-neglect-20200329-p2k3to6ukrbltm2n2va3ndbbim-story.html

- Cole CL, Levinson TR. Effects of within-activity choices on the challenging behavior of children with severe developmental disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2002;4:29–37. doi: 10.1177/109830070200400106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan A, Fuddy L, Burrell L, Higman SM, McFarlane E, Windham A, Sia C. Randomized trial of a statewide home visiting program to prevent child abuse: Impact in reducing parental risk factors. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28(6):623–643. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau, O. (2020). Foster care children at risk during COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.news5cleveland.com/news/coronavirus/foster-care-children-at-risk-during-covid-19-pandemic

- Hall RV, Fox R, Willard D, Goldsmith L, Emerson M, Owen M, et al. The teacher as observer and experimenter in the modification of disputing and talking-out behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1971;4(2):141–149. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1971.4-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester PP, Hendrickson JM, Gable RA. Forty years later—the value of praise, ignoring, and rules for preschoolers at risk for behavior disorders. Education and Treatment of Children. 2009;32(4):513–535. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Homme LE, Debaca PC, Devine JV, Steinhorst R, Rickert EJ. Use of the Premack principle in controlling the behavior of nursery school children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 1963;6:544. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1963.6-544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern L, Mantegna ME, Vorndran CM, Bailin D, Hilt A. Choice of task sequence to reduce problem behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2001;3:3–10. doi: 10.1177/109830070100300102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles, H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic creates shortage of foster parents. Retrieved from https://wwmt.com/news/coronavirus/covid-19-pandemic-creates-a-shortage-of-foster-parents

- Lalli JS, Casey S, Kates K. Reducing escape behavior and increasing task completion with functional communication training, extinction and response chaining. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28(3):261–268. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace FC, Pratt JL, Prager KL, Pritchard D. An evaluation of three methods of saying “no” to avoid an escalating response class hierarchy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44(1):83–94. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council . Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, J. (2020). Alabama foster care system feeling affects [sic] from the COVID-19 outbreak. Retrieved from https://www.wsfa.com/2020/03/26/alabama-foster-care-system-feeling-affects-covid-outbreak/

- Shukla S, Albin RW. Effects of extinction alone and extinction plus functional communication training on covariation of problem behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1996;29(4):565–568. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel M, Yoo J, Bolger K. Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment. 2004;9(4):395–408. doi: 10.1177/1077559504269193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speights Roberts D, Tingstrom DH, Olmi DJ, Bellipanni KD. Positive antecedent and consequent components in child compliance training. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(1):21–38. doi: 10.1177/0145445507303838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson KM, Hanley GP. Preschoolers’ compliance with simple instructions: A descriptive and experimental evaluation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43(2):229–247. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbox RS, Wallace MD, Penrod B, Tarbox J. Effects of three-step prompting on compliance with caregiver requests. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40(4):703–706. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.703-706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 995 kb)