Abstract

Magnetogenetics is a new field that leverages genetically encoded proteins and protein assemblies that are sensitive to magnetic fields to study and manipulate cell behavior. Theoretical studies show that many proposed magnetogenetic proteins do not contain enough iron to generate substantial magnetic forces. Here, we have engineered a genetically encoded ferritin-containing protein crystal that grows inside mammalian cells. Each of these crystals contains more than 10 million ferritin subunits and is capable of mineralizing substantial amounts of iron. When isolated from cells and loaded with iron in vitro, these crystals generate magnetic forces that are 9 orders of magnitude larger than the forces from the single ferritin cages used in previous studies. These protein crystals are attracted to an applied magnetic field and move toward magnets even when internalized into cells. While additional studies are needed to realize the full potential of magnetogenetics, these results demonstrate the feasibility of engineering protein assemblies for magnetic sensing.

Keywords: Magnetogenetics, protein crystal, ferritin, magnetic

Graphical Abstract

Magnetogenetics employs a class of genetically encoded probes in live cells to manipulate cellular activities using external magnetic fields.1 Because living matter is largely unaffected by magnetic fields, a magnetogenetic method could potentially enable wireless, bio-orthogonal manipulation of living cells. Some previous methods use externally added magnetic particles, such as nanoparticles or prefilled ferritin cages, but the magnetic sensors in these studies are not genetically encoded.2–4 To date, several groups have proposed achieving magnetic manipulation of cellular activities using iron-containing proteins. Most studies use a ubiquitous iron-storage protein, ferritin, that is conserved from bacteria to mammals. Recent studies have used ferritin to generate either mechanical forces5 or radio-frequency-induced magnetothermal heat.6 Another iron-containing protein, Isca1, also known as MagR, was believed to be responsive to the application of magnetic fields,7,8 although this result was disputed by a later study.9

However, theoretical analysis shows that these assemblies contain too little iron to generate significant magnetic effects.10 Ferritin, the largest assembly used in these studies, is a ubiquitous iron storage protein, 24 of which self-assemble into a spherical cage with a 12 nm outer diameter, and an inner cavity approximately 8 nm in diameter. The iron oxide core of a ferritin cage can contain a maximum of 4500 iron atoms as ferrihydrite, though an average of 2000 iron atoms are usually present.11 Physical calculations show that, under the conditions reported in a previous study,5 a single ferritin cage generates forces that are 9 orders of magnitude too small to open a mechanosensitive ion channel.10 Likewise, the magnetothermal effect from a single ferritin cage is more than 10 orders of magnitude too small to affect a heat-sensitive ion channel.10 At the same magnetic field and field gradient, the magnetic force is linearly proportional to the amount of mineralized iron per particle. Therefore, a larger protein assembly that contains more mineralized iron will be able to generate larger magnetic forces.

Another family of naturally occurring protein assemblies are encapsulin cages. Encapsulins are analogous to enlarged ferritin cages, consisting of ~150 iron-mineralizing proteins attached to a 180-subunit capsid, expanding the diameter of the iron oxide core to 23 nm.12 Assuming that encapsulins store iron in the same manner as ferritin13 and using the calculation described above,10 the iron oxide core of encapsulin is capable of generating forces approximately 2 orders of magnitude larger than the iron oxide core of ferritin. While this increase is substantial, the force is still orders of magnitude too small for manipulating cell activities such as activating ion channels. On the other hand, the magnetite-containing magnetosomes of magnetotactic bacteria have been shown to be strongly magnetic, but magnetosome formation is complex and involves many genes, hindering their direct implementation in mammalian cells,14 though Elfick et. al have shown that transfection with the magnetobacterial protein mms6 can produce some magnetic nanoparticles.15

To address the issue of insufficient iron storage for magnetic manipulation, we here have developed a system based on an in cellulo protein crystal. Recently, it has been shown that heterologously expressed proteins can form large crystalline complexes inside cells. These crystals have a variety of geometries and sizes, ranging from micron-sized cubes to 200 μm long spindles.16 Importantly, these crystals have far more subunits than ferritin or encapsulin cages. For example, Bombyx mori cypovirus polyhedrins are cubic crystals with edge lengths ranging from 1 to 7 μm,17 with an estimated 107 to 109 subunits per crystal. Inkabox-PAK4cat, which we will refer to as inka-PAK4, was originally described by Baskaran et. al and spontaneously forms needlelike crystals when expressed in mammalian cells.18 Notably, the unit cell of these crystals contains a hollow channel 8 nm in diameter. An inka-PAK4 crystal 2 μm wide and 50 μm long is estimated to contain on the order of 108 subunits. To date, such in cellulo crystals have been used for structure determination via X-ray diffraction18–22 as well as the encapsulation of various cargos.23,24

In this study, we engineered ferritin-containing protein crystals that drastically increase the amount of iron that a protein assembly can store. Each individual subunit of the Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin is capable of mineralizing iron25,26 and has been engineered to maximize iron content.27 We linked this mutated ferritin subunit to half of the subunits of the inka-PAK4 crystal. The resulting crystal, which we name ftn-PAK4, is one of the largest iron-mineralizing protein assemblies described, synthetic or otherwise. This iron content was detected by multiple analytical methods and enabled the crystals to be manipulated by external magnetic fields. Under our experimental conditions, these protein crystals exert magnetic forces that are 9 orders of magnitude larger than those in previous reports. This work demonstrates the feasibility of significantly enhancing the magnetic susceptibility of proteins. To realize the full potential of magnetogenetics, future studies are needed to overcome the limited availability of iron ions inside living cells.

Results

Ftn-PAK4 Crystals Form Robustly in Mammalian Cells

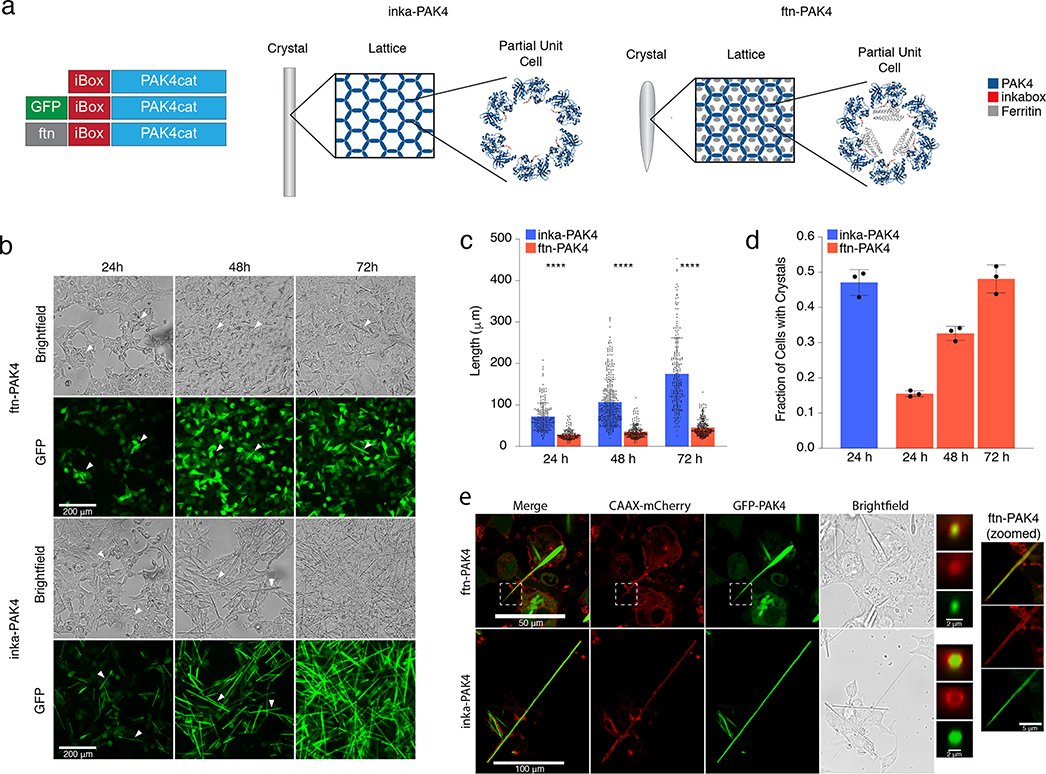

The initial inka-PAK4 crystal is composed of the catalytic domain of the Cdc42 effector PAK4 and the inkabox motif of the PAK4 inhibitor Inka1.18 When inkabox complexes with PAK4cat, conformational changes allow the spontaneous crystallization of the complex, producing long rod-shaped crystals with a unit cell that has a hexagonal arrangement of subunits around a hollow channel (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of the three plasmids used in ftn-PAK4: control inkabox-PAK4cat, GFP-tagged plasmid, and ferritin-linked plasmid, alongside a schematic of how the ferritin subunits might fit inside of the crystals’ hollow channel. (b) Phase-contrast and GFP images of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 growing in HEK293T cells over 72 h. White arrows highlight individual crystals. (c) Quantification of the length of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals over 72 h, with n > 150 crystals and p < 0.0001 for all conditions. (d) Quantification of the proportion of GFP-positive cells that grew ftn-PAK4 or inka-PAK4 crystals over time. Data beyond 24 h for inka-PAK4 crystals was omitted, as it became impossible to assign crystals to individual cells. Error bars are the standard deviation of 3 fields, containing between 150 and 700 cells each. (e) Confocal images of cells cotransfected with the membrane marker CAAX-mCherry and either inka-PAK4 or ftn-PAK4, imaged 72 h after transfection. The left inset images are averaged XZY cross-sections along the length of the crystal, for inka-PAK4, and along the portion of the crystal protruding beyond the cell body, for ftn-PAK4. The right inset images are slices taken from the same Z-stack as the ftn-PAK4 image, zoomed in on the boxed region to demonstrate membrane wrapping around the tapered tip.

We generated the iron storing version of this construct, which we call ftn-PAK4, by fusing a mutated Pyrococcus furiosus ferritin27 to the N-terminal inkabox portion of the inkabox-PAK4cat plasmid (Figure 1a). The hollow channels within inkabox-PAK4cat crystals are approximately 8 nm in size,18 suggesting that the resulting crystal may accommodate inward-facing ferritin subunits, which are approximately 5 nm long and 2 nm wide at their widest point (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2jd6), as well as a substantial amount of iron (Figure 1a).

As reported by Baskaran et. al, HEK293T cells transfected with the control inka-PAK4 plasmid grow long, individual needlelike crystals with lengths as long as 100 μm. Transfection with the ftn-PAK4 construct alone does not result in crystal growth, but cotransfection with both the ftn-PAK4 and the control inka-PAK4 plasmids does allow crystals to form (Figure S1a). To maximize the number of ferritin subunits while still maintaining robust crystal growth, we cotransfected cells with a 1:1 mass ratio of the ftn-PAK4 construct and the unmodified inka-PAK4. To more easily visualize the crystals, we also included a small amount of the GFP-PAK4 construct for an ultimate ratio of inka-PAK4:ftn-PAK4:GFP-PAK4 = 5:5:1. Thus, in the following results, unless otherwise noted, all ftn-PAK4 crystals are generated by transfection with a 5:5:1 inka-PAK4:ftn-PAK4:GFP-PAK4 plasmid ratio, and all of the inka-PAK4 crystals are generated using a 10:1 inka-PAK4:GFP-PAK4 plasmid ratio. The first cocrystals appear within 24 h post-transfection and continue to grow in length for up to 72 h post-transfection (Figure 1b).

The inclusion of ferritin caused significant changes in the growth rate and morphology of the protein crystal. Control inka-PAK4 crystals have an average length of 71.7 ± 32.9 μm at 24 h post-transfection, eventually reaching an average of 174.9 ± 86.9 μm at 72 h. On the other hand, ftn-PAK4 crystals were an average of 28 ± 11.9 μm long after 24 h and grew to an average of 45 ± 19.0 μm after 72 h (Figure 1b,c). At 24, 48, and 72 h post-transfection, the difference in length between ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 was found to be statistically significant using a two-tailed Kolmogorov—Smimov test, with p < 0.0001 and n > 150 crystals in all cases. Qualitatively, we noticed that ftn-PAK4 crystals tended to be shorter but wider than the control inka-PAK4 crystals, and many ftn-PAK4 crystals appeared to be significantly tapered at one end, whereas control crystals had squared-off ends and uniform widths. Additionally, ftn-PAK4 crystals appeared to nucleate more slowly than inka-PAK4 crystals. While 47.1 ± 3.6% of cells transfected with the control inka-PAK4 plasmid had visible crystals after 24 h, only 15.5 ± 0.83% of cells transfected with ftn-PAK4 had visible crystals after 24 h. After 72 h, 48.1 ± 4.0% of cells transfected with ftn-PAK4 had visible crystals (Figure 1d). In comparison to the ftn-PAK4 plasmid, cotransfection with GFP-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 did not significantly reduce the length of the resulting crystals. The triple transfection with 5:5:1 of inka-PAK4:ftn-PAK4:GFP-PAK4 resulted in an approximately 10 μm (18%) reduction in the crystal length compared with double transfection with 1:1 inka-PAK4:ftn-PAK4 at 72 h post-transfection (Figure S1b,c, p < 0.0001 using two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smimov test). Therefore, for visualization purposes in all following studies, we included the small fraction of GFP-PAK4.

Despite their large sizes, cotransfection with the membrane marker mCherry-CAAX and confocal imaging showed that ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals do not pierce the cell membrane, even when they are highly tapered, in the case of ftn-PAK4 (Figure 1e). Moreover, while individual cross-sections under a confocal microscope had a poor signal, the average projection of the cross-sections of the inka-PAK4 crystal indicates that the membrane (red signal from mCherry-CAAX) wrapped around the crystal (green signal from GFP-PAK4). Due to the substantial changes in cross-sectional width, only the tapered tip of the ftn-PAK4 crystal was averaged, also showing that the tip is surrounded by an intact membrane (Figure 1e). Live/dead staining of many cells showed that nearly all adherent cells with ftn-PAK4 or inka-PAK4 crystals are alive 72 h after transfection (Figure S2) (p > 0.9999 for 24 h post-transfection, and p = 0.60 for 48 and 72 h post-transfection, using the two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smimov test).

Isolated ftn-PAK4 Crystals Mineralize Iron

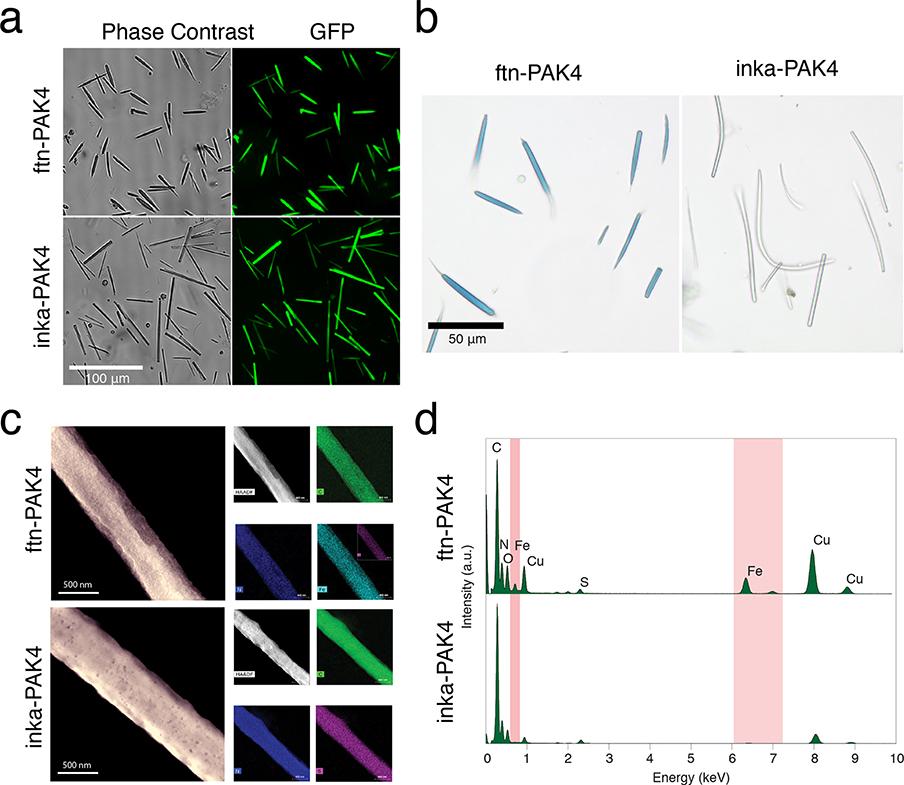

To characterize isolated PAK4 crystals, we released them from cells with a lysis buffer containing NP-40, DNase, and HEPES (Figure 2a), which breaks the cell membrane and frees the crystals. The crystals were then isolated from the resulting suspension through gentle centrifugation, so that most of the crystals were pelleted, but the cell debris remained in the solution. The crystal-containing pellet was resuspended in 0.1 M HEPES buffer and checked by visual inspection.

Figure 2.

(a) Representative images of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals after being isolated from cells. (b) Prussian blue staining of isolated ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals after exposure to iron. (c) STEM imaging of isolated ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals after iron exposure. The inset shows zoomed-in images. (d) EDX spectra of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals after iron exposure.

To verify the composition of the crystals, isolated inka-PAK4 and ftn-PAK4 crystals were denatured and analyzed using SDS-PAGE. In this experiment, GFP-PAK4 was omitted from both crystals because the GFP protein was similar in weight to the ferritin. The inka-PAK4 lane had only one band at the expected molecular weight of the inka-PAK4 subunit (Figure S3a). The ftn-PAK4 lane had two bands of similar intensities: the lower band corresponding to the inka-PAK4 subunit and a higher band corresponding to ftn-PAK4 subunits. These SDS-PAGE results confirm that ftn-PAK4 is composed of a mixture of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 subunits.

The ferritin subunits within isolated ftn-PAK4 crystals were able to mineralize and store iron. Ferritins are known to catalyze the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+.28 Thus, the isolated ftn-PAK4 crystals were exposed to 500 μM Fe2+ in the form of ferrous ammonium sulfate (FAS). Free Fe2+ was washed out before the crystals were assayed with Prussian blue (PB) staining for the presence of mineralized Fe3+. The ferrocyanide ions ([Fe(CN)6]−4) in the staining solution react with Fe3+ ions to produce the highly colored Prussian blue, allowing the fast, selective, and localized detection of iron. Under our color imaging conditions, both control inka-PAK4 and ftn-PAK4 crystals had a faint blue tint in the absence of PB staining (Figure S3b). However, iron-exposed ftn-PAK4 crystals stained a deep blue, indicating successful mineralization of iron. On the other hand, inka-PAK4 crystals exposed to identical iron conditions did not change in color (Figure 2b). As an added control, we cocultured cells expressing the two different types of crystals. One batch of cells was transfected with 100% inka-PAK4 as a control, while another batch was transfected with a 5:5:1 ratio of inka-PAK4, ftn-PAK4, and GFP-PAK4. These two populations of cells were trypsinized, mixed, replated, and cocultured in a single well to produce a mixed population of crystals. As shown in Figure S3b, the purified protein crystals were a mixture of ftn-PAK4 crystals (green fluorescent, arrow heads) and inka-PAK4 crystals (nonfluorescent, thin arrows). When a drop of Prussian blue solution was added to the mixture while the sample was under the microscope, only ftn-PAK4 crystals turned blue. This result further confirms that the presence of ferritin is necessary for ftn-PAK4 crystals to mineralize iron.

We next verified the presence of iron in ftn-PAK4 protein crystals using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). Together, these two techniques are used to map the distribution and identity of elements throughout the crystal and provide an independent confirmation of the presence of iron in ftn-PAK4 crystals. While the STEM images of both the unmodified crystals and ftn-PAK4 were generally similar in shape (Figure 2c), elemental analysis indicated that only the ftn-PAK4 crystal contained iron (Figure 2c), and the corresponding EDX spectra showed that only the ftn-PAK4 crystals had iron peaks (Figure 2d).

Iron-Loaded ftn-PAK4 Crystals Are Attracted by Magnetic Fields

As a result of their mineralized iron, ftn-PAK4 crystals can be magnetized and pulled by external magnetic fields. To observe this magnetic attraction, we built a simple device to maximize the magnetic field gradient applied to an isolated suspension of crystals during imaging (Figure 3a). This device was a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) well adhered onto a glass slide. A suspension of crystals was added to the well, and a coverslip coated with oil was pressed to the top, creating a sealed chamber. The oil coating prevented nonspecific adhesion to the top of the chamber. The assembly was then placed in a 3D-printed holder, which allowed a magnet to be brought in close proximity without actually touching the sample. At room temperature, the iron oxide core of ferritin is paramagnetic,29 so the magnetic force on the crystal is proportional to the crystal’s iron content and the magnitude and spatial gradient of the applied magnetic field.

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic and picture of the chamber built to image magnetic pulling of crystals. (b) Time-lapse imaging of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals in the magnetic imaging chamber, alongside bright-field images to indicate the position of the magnet. (c) Time-lapse of magnetic pulling of ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals acquired using confocal imaging. Each image is an XZ cross-section of a portion of the imaging area, with the magnet at the top of the image. (d) Plot of the frame-by-frame changes in z positions of representative ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals over time. (e) Plot of average z-velocity during movement, as measured by confocal imaging. n = 104 for iron-loaded ftn-PAK4, n = 73 for non-iron-loaded ftn-PAK4, n = 65 for iron-exposed inka-PAK4, and n = 69 for non-iron-exposed inka-PAK4.

To quantitatively estimate the magnetic field and field gradients in our setup, we simulated a permanent magnet using the open source software Finite Element Method Magnetics (FEMM).30 We estimated that the magnetic field strength was approximately 0.7 T, and the magnetic field gradient in the Z-direction was approximately 300 T/m at the top of the liquid chamber, dropping to 200 T/m at a depth of 200 μm (Figure S4). Compared to the magnetic field strength of ~0.05 T and ~6.6 T/m described in a previous study and calculated in Meister,5,10 our setup was able to apply approximately 600 times more force on a particle with the same iron content. Because the magnetic field gradient varies greatly with distance, we observed that the vertical distance between the magnet’s edge and the suspension was critically important, and an increase in this distance of 1 mm would abolish the observed magnetic pulling.

Wide-field time-lapse imaging of crystal suspensions in this setup demonstrated that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals were attracted toward the magnet’s edge (Figure 3b, Movie S1). In these videos, the focal plane was set to the top of the liquid suspension, just below the glass coverslip. From this perspective, ftn-PAK4 crystals loaded with iron were attracted upward, against gravity, and moved into focus toward the edge of the magnet where the magnetic gradient is the strongest. They continued along this trajectory until they came into contact with the coverslip at the top of the device, where they stopped. On the other hand, iron-exposed inka-PAK4 crystals in the same environment showed no lateral movement and instead drifted downward out of focus due to gravity. This magnetic pulling of ftn-PAK4 crystals is reversible: when the magnet was removed, the ftn-PAK4 crystals stopped their upward motion and began to drift downward, out of focus (Movie S2). Notably, after the magnet was removed, the crystals did not appear to have any magnetic influence on one another, confirming that the iron inside ftn-PAK4 is indeed paramagnetic.

Confocal time-lapse imaging confirms that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals moved upward, whereas iron-exposed inka-PAK4 crystals, iron-free ftn-PAK4 crystals, and iron-free inka-PAK4 crystals drifted downward (Figure 3c, Movies S3 and S4). The Z position trajectory plots indicate that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals moved upward at a constant velocity until they were stopped by the glass coverslip, whereas inka-PAK4 and iron-free ftn-PAK4 crystals slowly drifted downward (Figure 3d). The XY top-down time-lapse showed ftn-PAK4 crystals moving toward the magnet edge, as well as new crystals appearing as they were pulled into the imaged volume, whereas control crystals slowly disappeared as they fell below the imaged volume (Movie S3). By tracking many individual crystals for 172 s at 4.8 s per frame, we found that every iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystal moved upward, while all inka-PAK4 and iron-free ftn-PAK4 crystals moved downward. On average, iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals had a positive z-velocity of 4.11 ± 2.4 μm/s, whereas the controls had negative z-velocities of −1.29 ± 0.65, −0.86 ± 0.54, and −1.21 ± 0.74 μm/s for iron-free ftn-PAK4, iron-exposed inka-PAK4, and iron-free inka-PAK4, respectively (Figure 3e).

We used the z-velocity data to estimate the magnetic pulling forces applied to ftn-PAK4 crystals, and thus to estimate the iron content of the crystals. The motion of the crystal toward the magnet was modeled as the Stokes flow of a cylinder moving perpendicular to the direction of movement. In this scenario, the force on a particle is proportional to its velocity and a drag coefficient, which in turn depends on the length and aspect ratio of the cylinder:31

Where Fdrag is the pulling force, U is the velocity, η is the viscosity of the HEPES buffer (1.1×10–3 Pa s at 20 °C32), L and r are the length and radius of the cylinder, respectively, and γ is a constant correction factor of 1.193. For this calculation, 15 well-resolved crystals were selected from a 200 μm wide volume immediately below the magnet’s edge, so that the crystals were moving primarily in the Z direction. The length (31.36 ± 6.48 μm) and z-velocities (1.45 ± 0.54 μm/s) of these crystals were measured, and the diameter of each crystal was assumed to be 3 μm. From their lengths and velocities, we estimated that the magnetic pulling force on iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals is on the order of 10−13 N (1.76 ± 0.75 ×10−13 N). Because we neglected any effects from the nearby wall and gravity, the true pulling force is likely higher.

From this force, we can then estimate the iron content of a single crystal. As Meister described,10 the force produced by the magnetic field is

where ξ is the magnetizability of the iron within the crystal, B is the magnetic field, and is the magnetic field gradient in the z axis. Because the magnetic field and the forces are known, we can then calculate the magnetizability of the crystal, which is related to its iron content. We estimate that, with a force of 1.76×10−13 N, a magnetic field of 0.7 T, and a magnetic field gradient of 300 T/m, that the magnetizability of a ftn-PAK4 crystal was approximately 8.4×10−16 J/T. A single ferritin cage, with 2400 iron atoms, has a magnetizability of 2.35×10−22 J/T.10 Assuming that this magnetizability value is proportional to the number of iron atoms, we arrive at 8×109 iron atoms per crystal. If half of the ~108 subunits in a ftn-PAK4 crystal contain a ferritin subunit, this leads to an estimate of ~172 iron atoms per subunit. Notably, this value is consistent with ferritin, which also has approximately 100 iron atoms per subunit.

Iron-Loaded and Cell-Internalized ftn-PAK4 Conveys Magnetic Forces to Cells, but Iron-Loading in Live Cells Needs Further Work

The iron content and the magnitude of the resulting magnetic forces enabled us to magnetically manipulate living cells through the addition of preloaded ftn-PAK4 crystals. Iron-exposed ftn-PAK4 crystals were added to a monolayer culture of HEK 293T cells. After several hours, the crystals were either internalized or adhered to the cell surface. Cells were then stained with Cell-mask orange, trypsinized, and transferred to a new magnetic pulling setup, consisting of an open PDMS well and a permanent magnet mounted to a micromanipulator (Figure 4a). When the edge of the magnet was brought close to ftn-PAK4-containing cells, entire cell-crystal assemblies were pulled toward the magnet’s edge (Figure 4b: ftn-PAK4). On the other hand, cells containing iron-exposed control inka-PAK4 crystals were unaffected by the magnet (Figure 4b: inka-PAK4). Therefore, iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals contain enough iron to move living cells in suspension.

Figure 4.

(a) Photograph of the setup used for magnetic pulling of crystals on cells. (b) Cropped time-lapse of magnetic pulling. HEK 293T cells were labeled with Cellmask orange and incubated with a crystal suspension before trypsinization. White arrows indicate ftn-PAK4 crystals that have moved during the time-lapse. (c) Prussian blue stain of HEK 293T cells with ftn-PAK4 crystals exposed to different iron-loading conditions.

Having established that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals provide sufficient forces for magnetic manipulation of living cells, we next tried to deliver iron to ftn-PAK4 crystals inside live cells. First, we tried simply adding iron to the cell culture media, such as Ferrous Ammonium sulfate (FAS), a source of Fe2+, and ferrous ammonium citrate (FAC), a source of Fe3+, at varying concentrations up to 5 mM. The addition of 5 mM FAS to the culture media had a small but statistically significant effect on ftn-PAK4 crystal length at 72 h post-transfection, reducing the average length from 49.63 ± 17.93 μm in control conditions to 45.42 ± 23.19 μm in 5 mM FAS (Figure S5a, p < 0.0001 using the two-tailed Kolmogorov–Smimov test). Second, we attempted to mimic biological iron uptake, by combining FAS and FAC exposure with various agents that enhance iron uptake, such as human transferrin for Fe3+, and photodegraded nifedipine for Fe2+.33 Finally, we attempted to directly transport iron through the cell membrane using pyrithione in conjunction with FAS34 and 3,5,5-trimethyl-hexanoyl ferrocene (TMHF), a lipophilic iron delivery compound.35 Prussian blue staining of ftn-PAK4-containing cells showed that none of these strategies were able to load sufficient iron into ftn-PAK4 crystals (Figure 4c).

We also attempted to grow crystals and load iron in cell types other than HEK293T. We were able to grow ftn-PAK4 crystals in U2OS, PC-12, PC-3, Huh7, and RAW246.7 cells, although only a few crystals were observed in PC-12 and RAW264.7 cells (Figure S5b,c). However, we did not observe positive Prussian blue staining in ftn-PAK4 crystals in these cell lines after exposure to the iron-loading methods described above (Figure S5d). Thus, more studies are necessary to overcome the hurdle of iron loading of ftn-PAK4 crystals in live cells.

Discussion

We have engineered a genetically encoded protein crystal that is near-macroscopic in size and can generate magnetic forces many orders of magnitude larger than earlier studies. The ferritin subunits in these crystals retain their ability to mineralize iron, and time-lapse imaging shows that iron-loaded crystals can be attracted by a permanent magnet. Our study demonstrates that employing large protein assemblies such as ftn-PAK4 enables significant improvements in magnetic sensing.

Our experiments show that intracellular ftn-PAK4 crystal is not able to mineralize detectable amounts of iron within living cells. One possible explanation is that the concentration of free iron in cells may be too low. Because ftn-PAK4 crystals do not pierce the cell membrane, the only iron available to them is the labile iron pool, which is heavily buffered in the cytosol. The labile iron pool of various cell lines has been estimated to vary between 0.71 and 15.8 μM, depending on the cell type and cellular compartment.36,37 On the other hand, in vitro ironloading of ftn-PAK4 required a ferrous iron concentration on the order of 500 μM. Therefore, if magnetogenetics is to eventually rival the versatility of techniques like optogenetics or chemogenetics, this iron-loading hurdle must be overcome in living cells. While the ftn-PAK4 system does not yet enable in vivo, genetically targeted magnetic control of cell behavior, it is a significant step toward functional magnetogenetics. Future studies could resolve the iron-loading issue, with additional iron-loading proteins or other approaches, and the size of the ftn-PAK4 crystal could be tuned by optimizing the expression promoter or the overall protein expression level.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture

Low-passage (<15 passages) HEK293T, Huh7, U2OS, and RAW264.7 cells were cultured in 6-well plates in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2, with cell culture media composed of 10% fetal bovine serum in DMEM supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin. PC-3 cells were cultured in F-12K medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and PC-12 cells were cultured in F-12K medium supplemented with 15% horse serum and 2.5% fetal bovine serum. To produce protein crystals in HEK293T, U2OS, PC-3, PC-12, and Huh7 cells, cells were transfected overnight with Lipofectamine 2000 at a 1:3 DNA to Lipofectamine ratio. For inka-PAK4 crystals, cells were transfected with 2 μg of inka-PAK4 and 0.2 μg of GFP-PAK4, and for ftn-PAK4 crystals, cells were transfected with 1 μg of ftn-PAK4, 1 μg of inka-PAK4, and 0.2 μg of GFP-PAK4. To produce protein crystals in RAW264.7, cells were transfected using Targefect-RAW according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with a plasmid mix containing 30% ftn-PAK4, 60% inka-PAK4, and 10% GFP-PAK4. Percent growth and crystal length data in HEK293T cells were collected by manual measurements in ImageJ.

For confocal imaging, cells were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated glass-bottom dishes and transfected as above, with an additional 0.1 μg of CAAX-mCherry plasmid. Cells were fixed for 15 min with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution 72 h after transfection, and Z-stacks were acquired using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope. To produce averaged cross-sections, an XZ reslice was calculated from the Z-stack using ImageJ, and the crystal was aligned using the Manual Drift Correction plugin before averaging.

For in cellulo iron loading, cells were plated on poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips in a 24-well plate. 24 h after transfection, the media was replaced, and freshly prepared stock solutions containing iron and iron uptake agents were added to the media. In the experiments shown in Figure 4a, both FAS and FAC were added at a concentration of 5 mM. Transferrin was added at 1 mg/mL and pyrithione at 5uM, and photodegraded nifedipine and TMHF were added at 100 μM.

After 24 h in iron-loading media, the cells were fixed for 15 min with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, rinsed with PBS, and exposed to a Prussian blue staining solution (5% concentrated HCl v/v, 1% potassium ferrocyanide w/v in deionized water) for 20 min. The cells were rinsed twice with PBS and imaged using a Keyence BZX-800 microscope.

Ftn-PAK4 Purification and Iron Loading

Both types of PAK4 crystals were purified using the same protocol. At 72 h after transfection, cells were rinsed with sterile DI water, and 500 μL of lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 0.1 M HEPES, 125 U DNase at pH 7.4) was added. The cells were then placed on a rocker for 40 min. After rocking, the suspensions were transferred to an Eppendorf tube and centrifuged on a swinging-bucket benchtop centrifuge at 400g for 1 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 500 μL of a 0.1 M HEPES buffer at pH 7.4. For all of the data shown here, the crystals were isolated on the day of the experiment, but the crystal suspension can be stored at 4 °C for at least 3 days without obvious degradation.

To run an SDS-PAGE gel, isolated crystal suspensions were incubated with Laemmli buffer for 5 min at 95 °C. The samples were then loaded in a 10% polyacrylamide gel prepared using a Bio-Rad TGX stain-free FastCast acrylamide kit and run at 125 V for 1 h. The resulting gel was imaged using a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc MP imaging system.

To load iron, an iron stock solution was added to a 100 μL aliquot of the crystal suspension. The stock solution consists of 50 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate (FAS) and 500 mM mannitol dissolved in deionized water and was diluted by a factor of 100 for a final concentration of 500 μM FAS and 5 mM mannitol in the crystal suspension. Mannitol was added to reduce the auto-oxidation of iron in the HEPES buffer,38 but the stock must still be freshly prepared before each experiment. After 15 min, the iron-containing crystal suspension was centrifuged at 400g for 1 min in a swinging-bucket centrifuge. The supernatant was discarded, and the crystal-containing pellet was resuspended in fresh HEPES buffer. The centrifugation was repeated to wash any excess iron from the solution. Centrifugation at this stage must be minimized, as excessive centrifugation will cause the control crystals to become magnetic.

For Prussian blue staining, the same staining solution described above was added at a 1:1 ratio to a 5 μL droplet of crystal suspension on a glass slide. The droplet was left at room temperature for 5 min to allow staining to occur and the crystals to settle before imaging.

STEM and EDX

After exposing the ftn-PAK4 crystals to the iron-loading solution, ftn-PAK4 samples were dropped on a standard TEM grid holder with a continuous thin carbon layer and washed thoroughly with Milli-Q water. As a control, inka-PAK4 were also exposed to the iron solution under the same conditions. The morphology of the crystals was obtained using conventional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) on a FEI Talos F200A electron microscope with a TWIN lens system, X-FEG electron source, and Ceta 16m camera. With the combined super-X EDS detector, spatially resolved elemental analysis was collected after exposure time of 10 min.

Magnetic Pulling of Isolated Crystals

The magnetic pulling setup consists of a glass/PDMS chamber to hold the crystal suspension, a permanent magnet, and a 3D-printed slide holder.

To produce a PDMS well of the appropriate thickness, 2.5 g of Sylgard 184 at a 1:10 cross-linker ratio was poured into a 10 cm dish, degassed, and cured in a 60 °C oven. A hole was punched out of the PDMS using a 2 mm biopsy punch, and the resulting well was cut out with a razor and pressed onto a glass slide. In the meantime, a 12 mm 1.5 glass coverslip was coated with 2 μL of n-hexadecane (Acros Organics) and incubated at room temperature for 5 min.

Immediately before imaging, 7 μL of the crystal suspension was added to the PDMS well, and the well was capped using the oil-covered coverslip while avoiding bubbles. The assembly was moved to the 3D-printed slide holder and placed on the microscope. The magnet was placed on top of the holder; focus was acquired, and then the magnet was slid across the holder so that the edge of the magnet hung directly over the field of view. Time-lapse imaging was initiated immediately after the magnet was in place. Particle trajectories and velocities were manually tracked using ImageJ.

Magnetic Pulling of Crystals Attached to Cells

For crystal uptake/adhesion, iron-exposed crystals were washed twice with cell culture media by centrifuging at 400g for 1 min. The crystal suspension was added to a confluent monolayer of HEK cells and incubated for 2 h. After incubation, the cells were stained with Cellmask orange and trypsinized. The resulting cell/crystal suspension was transferred to a magnetic pulling setup.

The magnetic pulling setup for cells consisted of a PDMS well and a permanent magnet mounted to a micromanipulator. The PDMS well was created in the same manner as the one for isolated crystals, but with 10 g of Sylgard 184 and using a 10 mm biopsy punch to create a deeper and wider well. The well was pressed against a glass slide, and 0.1 mg/mL PEG–PLL was added to the well for 1 h to prevent cell adhesion to the slide. To mount the permanent magnet on a micromanipulator, a 3 mm cylindrical magnet was attached to the tip of a steel dental pick, and the dental pick was attached to a Sutter MP-225 micromanipulator with a 3D-printed spacer.

To observe magnetic pulling, the PEG–PLL solution was removed from the well, and the cell suspension was added. After the cells had settled to the bottom of the well, the bottom edge of the magnet was located through the microscope, and the magnet was lowered vertically into the well. Time-lapse imaging was started immediately after the edge of the magnet reached the bottom of the well.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1: demonstration that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals are attracted to a permanent magnet, while inka-PAK4 crystals are not (AVI)

Movie S2: demonstration that the upward movement of ftn-PAK4 crystals ceases when the magnet is removed (AVI)

Movie S3: 3D confocal time-lapse of iron-exposed ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals in the magnetic pulling setup (AVI)

Movie S4: 3D confocal time-lapse of iron-free ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals in the magnetic pulling setup (AVI)

Movie S5: HEK293T cells with ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals being pulled by a magnet (AVI)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Robert C. Robinson for providing the original inka-PAK4 and GFP-inka-PAK4 plasmids, and we thank Katherine Walker of Robert Waymouth’s lab for the synthesis of 3,5,5-trimethyl-hexanoyl ferrocene.

Funding

This work was funded by a Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship in association with the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute (T.L.L.), Packard Fellowship and Engineering (B.C.), and NIH 1R01GM125737 (B.C.).

ABBREVIATIONS

- FAS

ferrous ammonium sulfate

- PB

Prussian blue

- STEM

scanning transmission electron microscopy

- EDX

energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- PDMS

polydimethylsiloxane

- FEMM

finite element method magnetics

- FAC

ferrous ammonium citrate

- TMHF

3,5,5-trimethyl-hexanoyl ferrocene

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.nano-lett.9b02266.

Length measurements, live/dead staining, SDS-PAGE gel, Prussian blue staining, simulations of the magnetic field and field gradient, and images of ftn-PAK4 growth (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Nimpf S; Keays DA Is Magnetogenetics the New Optogenetics? EMBO J. 2017, 36 (12), 1643–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Munshi R; Qadri SM; Zhang Q; Castellanos Rubio I; Del Pino P; Pralle A Magnetothermal Genetic Deep Brain Stimulation of Motor Behaviors in Awake, Freely Moving Mice. eLife 2017, 6, 27069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Liße D; Monzel C; Vicario C; Manzi J; Maurin I; Coppey M; Piehler J; Dahan M Engineered Ferritin for Magnetogenetic Manipulation of Proteins and Organelles Inside Living Cells. Adv. Mater 2017, 29 (42), 1700189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Chen R; Romero G; Christiansen MG; Mohr A; Anikeeva P Wireless Magnetothermal Deep Brain Stimulation. Science 2015, 347 (6229), 1477–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wheeler MA; Smith CJ; Ottolini M; Barker BS; Purohit AM; Grippo RM; Gaykema RP; Spano AJ; Beenhakker MP; Kucenas S; et al. Genetically Targeted Magnetic Control of the Nervous System. Nat. Neurosci 2016, 19 (5), 756–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Stanley SA; Sauer J; Kane RS; Dordick JS; Friedman JM Remote Regulation of Glucose Homeostasis in Mice Using Genetically Encoded Nanoparticles. Nat. Med 2015, 21 (1), 92–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Qin S; Yin H; Yang C; Dou Y; Liu Z; Zhang P; Yu H; Huang Y; Feng J; Hao J; et al. A Magnetic Protein Biocompass. Nat. Mater 2016, 15 (2), 217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Long X; Zhang S-J Commentary: MagR Alone Is Insufficient to Confer Cellular Calcium Responses to Magnetic Stimulation. Front. Neural Circuits 2018, 12, 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Pang K; You H; Chen Y; Chu P; Hu M; Shen J; Guo W; Xie C; Lu B MagR Alone Is Insufficient to Confer Cellular Calcium Responses to Magnetic Stimulation. Front. Neural Circuits 2017, 11, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Meister M Physical Limits to Magnetogenetics. eLife 2016, 5, 17210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Jutz G; van Rijn P; Santos Miranda B; Böker A Ferritin: A Versatile Building Block for Bionanotechnology. Chem. Rev 2015, 115 (4), 1653–1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Giessen TW; Silver PA Widespread Distribution of Encapsulin Nanocompartments Reveals Functional Diversity. Nat. Microbiol 2017, 2, 17029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).He D; Hughes S; Vanden-Hehir S; Georgiev A; Altenbach K; Tarrant E; Mackay CL; Waldron KJ; Clarke DJ; Marles-Wright J Structural Characterization of Encapsulated Ferritin Provides Insight into Iron Storage in Bacterial Nanocompartments. eLife 2016, 5, 18972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Yan L; Zhang S; Chen P; Liu H; Yin H; Li H Magnetotactic Bacteria, Magnetosomes and Their Application. Microbiol. Res 2012, 167 (9), 507–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Elfick A; Rischitor G; Mouras R; Azfer A; Lungaro L; Uhlarz M; Herrmannsdörfer T; Lucocq J; Gamal W; Bagnaninchi P; et al. Biosynthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles by Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Following Transfection with the Magnetotactic Bacterial Gene mms6. Sci. Rep 2017, 7, 39755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Schönherr R; Rudolph JM; Redecke L Protein Crystallization in Living Cells. Biol. Chem 2018, 399 (7), 751–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Ji X; Axford D; Owen R; Evans G; Ginn HM; Sutton G; Stuart DI Polyhedra Structures and the Evolution of the Insect Viruses. J. Struct. Biol 2015, 192 (1), 88–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Baskaran Y; Ang KC; Anekal PV; Chan WL; Grimes JM; Manser E; Robinson RC An in Cellulo-Derived Structure of PAK4 in Complex with Its Inhibitor Inka1. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tsutsui H; Jinno Y; Shoda K; Tomita A; Matsuda M; Yamashita E; Katayama H; Nakagawa A; Miyawaki A A Diffraction-Quality Protein Crystal Processed as an Autophagic Cargo. Mol. Cell 2015, 58 (1), 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Boudes M; Garriga D; Fryga A; Caradoc-Davies T; Coulibaly F A Pipeline for Structure Determination of in Vivo-Grown Crystals Using in Cellulo Diffraction. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct Biol 2016, 72 (4), 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mori H; Ito R; Nakazawa H; Sumida M; Matsubara F; Minobe Y Expression of Bombyx Mori Cytoplasmic Polyhedrosis Virus Polyhedrin in Insect Cells by Using a Baculovirus Expression Vector, and Its Assembly into Polyhedra. J. Gen. Virol 1993, 74 (1), 99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Koopmann R; Cupelli K; Redecke L; Nass K; Deponte DP; White TA; Stellato F; Rehders D; Liang M; Andreasson J; et al. Vivo Protein Crystallization Opens New Routes in Structural Biology. Nat. Methods 2012, 9 (3), 259–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Ijiri H; Coulibaly F; Nishimura G; Nakai D; Chiu E; Takenaka C; Ikeda K; Nakazawa H; Hamada N; Kotani E; et al. Structure-Based Targeting of Bioactive Proteins into Cypovirus Polyhedra and Application to Immobilized Cytokines for Mammalian Cell Culture. Biomaterials 2009, 30 (26), 4297–4308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Abe S; Tabe H; Ijiri H; Yamashita K; Hirata K; Atsumi K; Shimoi T; Akai M; Mori H; Kitagawa S; et al. Crystal Engineering of Self-Assembled Porous Protein Materials in Living Cells. ACS Nano 2017, 11 (3), 2410–2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Tatur J; Hagen WR; Matias PM Crystal Structure of the Ferritin from the Hyperthermophilic Archaeal Anaerobe Pyrococcus Furiosus. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2007, 12 (5), 615–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Ebrahimi KH; Hagedoorn P-L; Hagen WR Self-assembly is prerequisite for catalysis of Fe(II) oxidation by catalytically active subunits of ferritin. J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290 (290), 26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Matsumoto Y; Chen R; Anikeeva P; Jasanoff A EngiEbrahiminK. H.eering Intracellular Biomineralization and Biosensing by a Magnetic Protein. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Honarmand Ebrahimi K; Hagedoorn P-L; Hagen WR Unity in the Biochemistry of the Iron-Storage Proteins Ferritin and Bacterioferritin. Chem. Rev 2015, 115 (1), 295–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Michaelis L; Coryell CD; Granick S; Ferritin III The Magnetic Properties of Ferritin and Some Other Colloidal Ferric Compounds. J. Biol. Chem 1943, 148 (3), 463–480. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Meeker D Finite Element Method Magnetics: HomePage. http://www.femm.info/wiki/HomePage.

- (31).Yang K; Lu C; Zhao X; Kawamura R From Bead to Rod: Comparison of Theories by Measuring Translational Drag Coefficients of Micron-Sized Magnetic Bead-Chains in Stokes Flow. PLoS One 2017, 12 (11), No. e0188015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kurniawan NA; van Kempen THS; Sonneveld S; Rosalina TT; Vos BE; Jansen KA; Peters GWM; van de Vosse FN; Koenderink GH Buffers Strongly Modulate Fibrin Self-Assembly into Fibrous Networks. Langmuir 2017, 33 (25), 6342–6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Savigni DL; Morgan EH Mediation of Iron Uptake and Release in Erythroid Cells by Photodegradation Products of Nifedipine. Biochem. Pharmacol 1996, 51 (12), 1701–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kress GJ; Dineley KE; Reynolds IJ The Relationship between Intracellular Free Iron and Cell Injury in Cultured Neurons, Astrocytes, and Oligodendrocytes. J. Neurosci 2002, 22 (14), 5848–5855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Malecki EA; Cable EE; Isom HC; Connor JR The Lipophilic Iron Compound TMH-Ferrocene [(3,5,5-Trimethylhexanoyl)ferrocene] Increases Iron Concentrations, Neuronal L-Ferritin, and Heme Oxygenase in Brains of BALB/c Mice. Biol. Trace Elem. Res 2002, 86 (1), 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Ma Y; Abbate V; Hider RC Iron-Sensitive Fluorescent Probes: Monitoring Intracellular Iron Pools. Metallomics 2015, 7 (2), 212–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Shi H; Bencze KZ; Stemmler TL; Philpott CC A Cytosolic Iron Chaperone That Delivers Iron to Ferritin. Science 2008, 320 (5880), 1207–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Tadolini B Iron Autoxidation in Mops and Hepes Buffers. Free Radical Res. Commun 1987, 4 (3), 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Movie S1: demonstration that iron-loaded ftn-PAK4 crystals are attracted to a permanent magnet, while inka-PAK4 crystals are not (AVI)

Movie S2: demonstration that the upward movement of ftn-PAK4 crystals ceases when the magnet is removed (AVI)

Movie S3: 3D confocal time-lapse of iron-exposed ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals in the magnetic pulling setup (AVI)

Movie S4: 3D confocal time-lapse of iron-free ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals in the magnetic pulling setup (AVI)

Movie S5: HEK293T cells with ftn-PAK4 and inka-PAK4 crystals being pulled by a magnet (AVI)