Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a highly pathogenic, transmittable and invasive pneumococcal disease caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which emerged in December 2019 and January 2020 in Wuhan city, Hubei province, China and fast spread later on the middle of February 2020 in the Northern part of Italy and Europe.

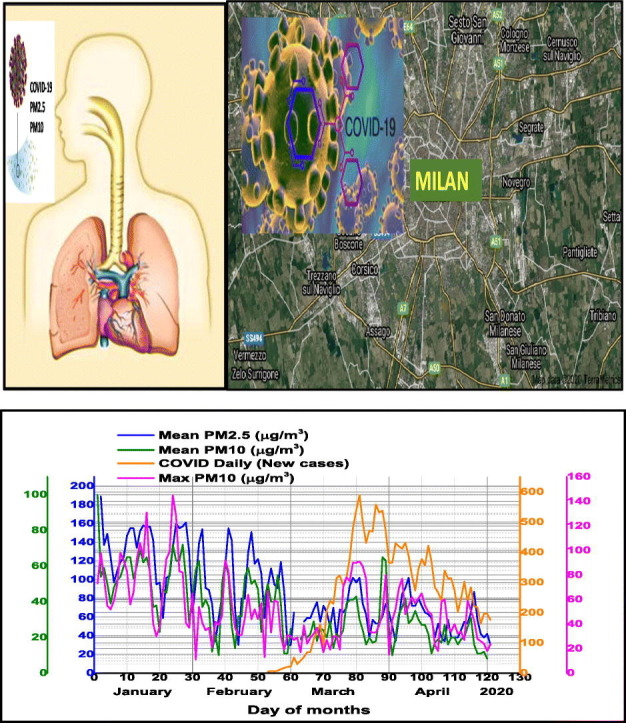

This study investigates the correlation between the degree of accelerated diffusion and lethality of COVID-19 and the surface air pollution in Milan metropolitan area, Lombardy region, Italy. Daily average concentrations of inhalable particulate matter (PM) in two size fractions PM2.5, PM10 and maxima PM10 ground level atmospheric pollutants together air quality and climate variables (daily average temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, atmospheric pressure field and Planetary Boundary Layer-PBL height) collected during 1 January–30 April 2020 were analyzed. In spite of being considered primarily transmitted by indoor bioaerosols droplets and infected surfaces, or direct human-to-human personal contacts, it seems that high levels of urban air pollution, weather and specific climate conditions have a significant impact on the increased rates of confirmed COVID-19 Total number, Daily New and Total Deaths cases, possible attributed not only to indoor but also to outdoor airborne bioaerosols distribution. Our analysis demonstrates the strong influence of daily averaged ground levels of particulate matter concentrations, positively associated with average surface air temperature and inversely related to air relative humidity on COVID-19 cases outbreak in Milan. Being a novel pandemic coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) version, COVID-19 might be ongoing during summer conditions associated with higher temperatures and low humidity levels. Presently is not clear if this protein “spike” of the new coronavirus COVID-19 is involved through attachment mechanisms on indoor or outdoor airborne aerosols in the infectious agent transmission from a reservoir to a susceptible host in some agglomerated urban areas like Milan is.

Keywords: Coronavirus COVID-19, Particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Air quality, Meteorological parameters, NOAA satellite data

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

COVID-19 daily New cases are positively related with PM and Air Quality Index.

-

•

Dry air supports COVID-19 virus transmission.

-

•

Warm season will not stop COVID-19 spreading.

-

•

Outdoor airborne aerosols might be possible routes of COVID-19 diffusion.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) global outbreak ongoing progression at an accelerating rate in Europe, United States of America as well as in the other regions of the world, started as an epidemic event in the city of Wuhan, China in late December 2019 and evolved as a pandemic declared by March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020).

On 8 May 2020, global confirmed COVID-19 number of cases was 3,942,907, including 271,646 deaths was reported from >200 countries/territories worldwide and only few countries appear to have passed the peak. On 8 May 2020 in Italy have been recorded 29,958 fatalities and a total of 215,858 confirmed COVID-19 cases, of which total confirmed cases 20,893 in Milan metropolitan area (Lombardy), representing 9.7% of Italy counts. In Italy outbreak of COVID-19 started in Lombardy county, first 3 COVID-19 cases have been reported on 15th February 2020 year. The invasive pneumococcal disease caused by novel coronavirus (COVID-19) is a highly contagious disease, having some similarities with previous coronaviruses recorded during periods 2002–2003, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV) and 2012–2015, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV), but with some differences in its genomic and phenotypic structure, that can influence their pathogenesis (Huang et al., 2020;Y. Wang et al., 2020; Mehta et al., 2020).

Epidemiological and toxicological studies continues to support a link between urban air pollution due to combustion traffic related products or other anthropogenic sources pollutants, that can induce airway inflammation and airway hyper-responsiveness and the increased incidence and/or severity of respiratory and cardiovascular disease (Seposo et al., 2020; McDonnell et al., 1983; Kulle et al., 1985; Kinney et al., 1996; Peters et al., 1999; Tager, 2005). Several researches suggest a strong correlation between exposure and specific characteristics of ecotoxicity, genotoxicity, and oxidative potential of particle matter, and an increased susceptibility to and morbidity from respiratory infection (Romano et al., 2020). Recent advances in mechanisms associated with airway disease due to PM2.5 and PM10 considered epigenetic alteration of genes by combustion-related pollutants and how polymorphisms in genes involved in antioxidant pathways and airway inflammation can modify responses to air pollution exposures (Kelly and Fussell, 2011; Xie et al., 2018). Besides local air pollution sources, meteorological factors, planetary (atmospheric) boundary layer (PBL) processes and regional/long range transport play important roles in determining the particulate matter (PM2.5 and PM10) concentrations function on the topography of the observational site.

Among air pollutants, the current focus is mainly given on particulate matter (PM) in the two size fractions PM2.5 and PM10 together with Air Quality Index (AQI), which frequently occur at elevated values in Milan metropolitan region in Italy. Also, this study considers the impact of climatic factors on fast spreading of COVID-19 outbreak in Milan. In order to assess the effects of air pollution on COVID-19 fast diffusion and fatality, have been examined the time series of daily mean PM2.5 and PM10 data together daily PM10 maxima values and AQI in relation with daily surface gaseous pollutants (ozone, nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide) concentrations, Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL), meteorological variables, over the study period 1 January–30 April 2020.

The goal of this paper is to provide scientific evidence regarding the influence of ground surface particulate matter and air quality on fast diffusion of COVID-19 in Milan metropolitan region, and the future progression under the changing circumstances of climate factors in the urban agglomerated areas. With increasing cases of infection with 2019-nCoV, several studies have proposed that human-to-human transmission via respiratory droplets, or human to infected surfaces are the probable route for the COVID-19 outbreak (Shereen et al., 2020), rather than through the air. This study aims to show that besides demonstrated indoor transmission (Li et al., 2004; Asadi et al., 2020), outdoor airborne viral diffusion (Sundell et al., 2016), might be considered a possible pathway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. COVID-19 and air pollution with particulate matter

2.1.1. COVID-19

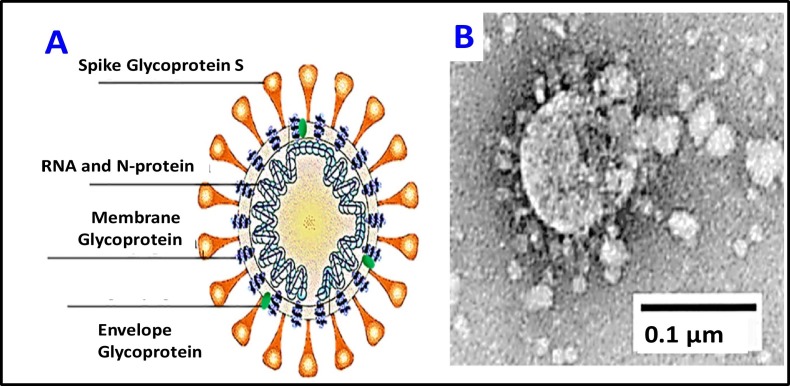

The new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 named COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ), is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus associated with a nucleoprotein within a capsid comprised of matrix protein (Mousavizadeh and Ghasemi, 2020) and is in the betaCoV genus. The associated fatalities of COVID-19 might be related to cytokine storm syndrome (Guo et al., 2016; Mehta et al., 2020), also known as hypercytokinemia, which is characterized by an uncontrolled release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Tisoncik et al., 2012), being a severe reaction of the immunity system, leading to death. Its genomic similarities to previous versions Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2012 could explain the aggressive inflammatory response of severe pneumonia (Zowalaty and Järhult, 2020). The pathogenesis of COVID-19 deadly epidemics is not yet clear (Nishiura et al., 2020). The life cycle of SARS-CoV-2 in human lung cells consists in several phases including: inhalation, infiltration from the upper respiratory tract, spike proteins of SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 receptors, releases RNA genome into the cells (epithelial of alveoli, trachea, bronchi, and bronchial serous glands of the respiratory tract) and translation of structural and non-structural proteins. The virus enters and replicates in these cells. The new developed virions are then released and infect new target cells (C. Lu et al., 2020; H. Lu et al., 2020; R. Lu et al., 2020; Shereen et al., 2020). The complex spectrum of new coronavirus COVID-19 symptomatic ranges from mild respiratory tract infection to severe pneumonia that may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome or multi-organ dysfunction.

Fig. 1.

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) structure and electron microscopy image.

For COVID-19 fast transmission spreading must be considered the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 binding to the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) via its spike protein, which allow the virus to invade lung cells in the oropharyngeal epithelia (Shang et al., 2020; Wrapp et al., 2020; Bosch et al., 2003; Rivellese and Prediletto, 2020). In addition to providing an entry door for SARS-CoV-2, ACE2 could be also involved in the pathogenesis of COVID-19, as it has been clearly implicated in the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome, atypically invasive pneumonia developed in the course of infection (Xu et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2020). Also, COVID-19 virus is considered to be aerosolized through talking or exhalation, which explains its pathogenicity. Existing scientific studies demonstrated that viral or bacterial bioaerosols can act on the human immune system through damage of innate immune recognition receptors that respond to unique pathogen-associated molecular patterns. Due to bioaerosols ubiquitous nature, can be found in most of the indoor but also and outdoor environments (Jones and Harrison, 2004). The size of the COVID-19 has been determined under Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) to be 60–140 nm, which averages to 0.1 μm (Fig. 1). As the virus can be attached to particulates < 0.1 μm, the smallest size for the COVID-19 and its carrier (droplet or particle) can still be about 0.1 μm. Current studies have shown that the primary transmission routes of COVID-19 might be by respiratory droplets sprays (sneeze or a cough) - aerosol of virus laden respiratory tract fluid, typically >5 μm in diameter transmission (Vejerano and Marr, 2018; Harrison et al., 2005), as well as human-human transmission, and transmission by touch infected surfaces (while specific climate conditions (as wind speed, humidity, temperature) can be top predictors of airborne coronavirus illnesses diffusion) (Poole, 2020). Air particulate matter PM (PM0.1, PM2.5 and PM10) can attach viruses as well as bacteria.

With increasing cases of infection with 2019-nCoV, several studies have proposed that human-to-human transmission via respiratory droplets, or human to infected surfaces are the probable route for the COVID-19 outbreak (Shereen et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; C. Lu et al., 2020), rather than through the air. This study aims to show that besides demonstrated indoor transmission, outdoor airborne viral diffusion is a possible pathway.

2.1.2. Particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10

Particle matter (PM) air pollution is more complex, covering a large size range. It consists of a multi-component matrix originating from various anthropogenic (power generation, traffic-related, etc.) and natural sources (biomass combustion, dust, etc.) being subject to several atmospheric processes. In many urban agglomerated areas, PM concentration is normally dominated by different size fractions (the ultrafine particles PM0.1 with diameter < 0.1 μm; fine particles PM2.5 with diameter ≤ 0.2.5 μm; coarse particles PM10 with diameter > 0.2.5 μm and ≤10 μm (Zoran et al., 2019; Khan et al., 2019). Fine and coarse PM inhalable ambient particles are associated with increased morbidity and mortality. In addition to a variety of organic chemicals, salts, and metals, inhalable ambient particles may contain biological species, such as proteins, lipids, and so on, from plants, bacteria, viruses and fungi. In airborne particles, the total mass of biological species is small, but their allergenic and inflammatory potential is strong (Yoshizaki et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2016).

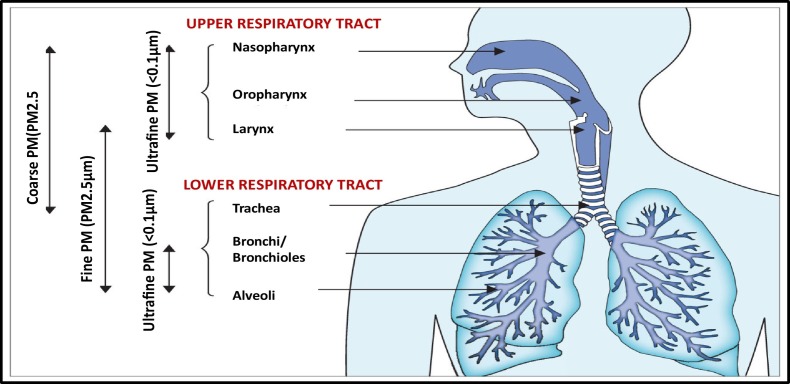

In order to for understand the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases associated with air pollution due to particulate matter PM in different size fractions, several studies examined the mechanisms responsible for incidence of respiratory system inflammation (Liu et al., 2020; Deng et al., 2019; Zoran et al., 2013; Zoran et al., 2014; Sugiyama et al., 2020). In terms of size distribution, ambient particulate matter (PM) is atmospheric aerosol with both anthropogenic and natural sources categorised on the basis of its aerodynamic diameter, with implications for its typical site of deposition when inhaled (Fig. 2 ) (Ballabio et al., 2013). Also, PM is a heterogeneous complex mixture of suspended particles of different size, chemistry, shape and great spatio-temporal variability (Pope et al., 2009; Potukuchi and Wexler, 1995; Janssen et al., 2011).

Fig. 2.

Compartmental deposition of particulate matter in different size fraction on the respiratory tract.

Coarse PM, with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5–10 μm, deposits mainly in the upper and large conducting airways. The PM10 fraction is widely used as air quality indicator. Fine PM or PM2.5 μm deposit throughout the lower respiratory tract, particularly in small airways and alveoli.

Ultrafine PM (PM0.1 μm) might be deposited both in the upper as well as in the lower respiratory tract (Zoran et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2016; Longhin et al., 2018; Prabhu and Shridhar, 2019; C. Lu et al., 2020; H. Lu et al., 2020; R. Lu et al., 2020). Due to their chemical composition and sometimes associated bacteria and viruses, epidemiological studies reveal that fine particles PM2.5 have adverse health effects because through inhalation, they can easily be deposited deeply in the human lungs (in lowest for adults and upper for infants), thus increasing the risk for cardiorespiratory diseases. PM2.5 consists from an inert carbonaceous core covered by sulfate, nitrate, organic chemicals, metals, and crustal elements, with possible adsorbed additional organic pollutants, bacteria, viruses and toxic heavy metals on its surface, that might enhance its toxicity (Ballabio et al., 2013, Cao et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2016; Zou et al., 2016; Zoran et al., 2019). Fine particulate matter PM2.5, but also coarse PM10 are considered air pollution indicators associated with a series of adverse health effects like as inflammation, oxidative damage, and DNA damage, which trigger pulmonary, cardiovascular and nervous system diseases, explained through cytotoxicity mechanisms. Inhaled atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) or coarse (PM10) includes total, soluble and insoluble fractions, which might interact with lung cells and cause adverse respiratory effects (Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018). From physiochemical point of view, the soluble fraction mainly contains water soluble ions and organic acids, while the insoluble fraction mainly contains kaolinite, calcium carbonate and some organic carbon, responsible for a higher cell mortality and serious cell membrane damage than the soluble fraction. The levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) enhanced by the two fractions are not significantly different.

Long-term chronic exposure to air pollutants in Milan metropolitan region might have a significant role in the spread of Covid-19. Also, just short –term exposure to high levels of ground particulate matter concentrations found in ambient air is associated with a reduction in lung function and induction of respiratory symptoms including cough, shortness of breath and pain on deep inspiration (Kelly and Fussell, 2011; Seposo et al., 2020). In case of children, inertial impaction is the dominant deposition mechanism, thus particles are deposited more in the upper airways, while in adults cases due to gravitational sedimentation mechanism, particles are deposited more in the lower airways than in the upper (Sugiyama et al., 2020; Khan et al., 2019; Yoshizaki et al., 2017). Short-term or long-term PM exposure and toxicity highly depends on the geographic location, season and local or regional air masses dynamics (Janssen et al., 2011). The weather conditions, like atmospheric inversions, haze or fog conditions as well as strong intensity winds responsible for transborder of high pollutants concentrations, which are favorable for enhanced deposition of ambient submicron aerosols (and infectious aerosols too) can be linked with seasons of viral respiratory infections and increased respiratory symptoms of asthma and COPD.

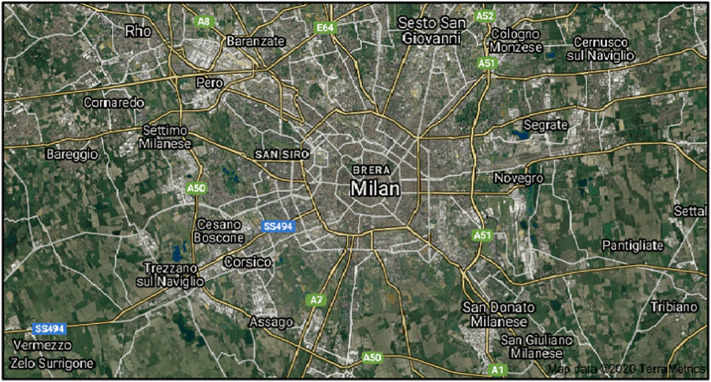

2.2. Investigation test site

Milan (45° 28′N, 9° 13′E), test site (Fig. 3 ) is placed in the Po Valley region, a high industrialized and agricultural large area in the Northern part of Italy. Milan urban area has about 1,5 million inhabitants, being the second largest town in Italy, after Rome, and considering the whole Milan metropolitan area the population is about 3.1 million inhabitants. The peculiar geomorphologic features of the Po river plain, surrounded on three sides by the Alps and Apennines mountain chains, causes the accumulation of high levels of pollutants in the air, especially particulate matter PM10 and PM2.5, as well gaseous pollutants nitrogen dioxide (NO2), ozone (O3), carbon monoxide (CO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), which in the last decades have always exceeded the limits indicated in the Directive 2008/50/EC. Specific local phenomena like haze, photochemical smog and other types of atmospheric pollution frequently occur over the region, enhancing chronic exposure of inhabitants to increased risk at respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Fig. 3.

Milan test site.

2.3. Data used

Time series data of daily average air pollutants PM2.5, PM10, O3 and NO2 for Milan selected station (Pascal Cita) have been collected from https://aqicn.org/city/italy/lombardia/milano-pascal-citta-studi/. Almost real time data for coronavirus COVID-19 Total, Daily New and fatalities cases recorded in Italy, Lombardia county and Milano have been provided by the following websites:https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/italy/and https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109295/provinces-with-most-coronavirus-cases-in-italy/.

Time series meteorological data, including daily average temperature (T), daily average relative humidity (H), daily average wind speed for Milan metropolitan region were retrieved from Weather Underground (https://www.wunderground.com/). The Omega surface charts for Europe at 850 mb and 925 mb have been provided by NASA, NOAA/OAR/ESRL PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/). According to content of meteorological information, downwards airflows are given by positive values of omega (in Pa/s), while upwards airflow by negative values of omega surface charts. Planetary Boundary Layer PBL data were collected from the archived data of NOAA's Air Resources Laboratory (https://ready.arl.noaa.gov). In order to analyze Milan weather conditions in the lower atmosphere associated with people's exposure to air pollutants during 1 January–25 April investigated period we used Omega surface charts provided by NASA satellites for vertical air masses motion assessment relative to Earth's surface at different levels: 825 hPa chart (at an altitude of approximately 1.5 km), 925 hPa chart (at an altitude of approximately 0.762 km) and 1000 hPa chart (at about sea level height). Origin 10 software and statistical methods have been used for time series data analysis.

In order to describe urban air quality of Milan metropolitan area in Italy, this paper considered Global Air Quality Index (AQI) according to classification of air quality (http://www.eurad.uni-koeln.de) and EU regulations, which is defined by formula:

| (1) |

where O 3(24 h), PM10(24 h), NO 2(24 h), SO 2(24 h), CO(24 h) represent daily mean values of respectively ozone, particle matter in size 10 μm, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide and carbon monoxide present in the urban air. Based on the global criteria for main air pollutants (O3, PM10, NO2, SO2, CO) air quality is classified in six classes from very good to very poor (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Air Quality Index (AQI) classification.

| AQI | <10 | 10–20 | 20–30 | 30–50 | 50–80 | >80 |

| Class | Very good | Good | Satisfactory | Sufficiently | Poor | Very poor |

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Descriptive statistics analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with ORIGIN 10 software. Experimental results for particle matter, climate variables as well as COVID-19 counts were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). The spatial analysis has been conducted on a regional scale for Milan metropolitan region, one of the most densely populated municipalities of Lombardy province with the highest COVID-19 cases included in the analysis and the highest COVID-19 rate from Italy.

Table 2 presents particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations recorded in Milan during the two time periods January–February 2020 and March–April 2020 (pre-lockdown and beyond lockdown). Average recorded during 1 January–30 April 2020 time period daily mean temperature, relative humidity, Planetary Boundary Level, wind speed and Air Quality Index were respectively 8.79 ± 4.89 °C, 69.42 ± 17.06%, 811.83 ± 553.53 m, 6.70 ± 3.4 km/h, and 37.03 ± 19.82.

Table 2.

Particulate matter PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations recorded in Milan during the two time periods (pre-lockdown and beyond lockdown).

| January–February 2020 | March–April 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily average particulate matter PM2.5 (μg/m3) | Mean value: 112.75 ± 38.5 | The range 30–189 | Mean value: 61.89 ± 18.03 | The range 34–102 |

| Daily average particulate matter PM10 (μg/m3) | Mean value: 46.78 ± 17.7 | The range 10–100 | Mean value: 24.78 ± 11.25 | The range 8–65 |

| Daily maxima particulate matter PM10 (μg/m3) | Mean value: 60.63 ± 29.6 | In the range 11–145 | Mean value: 44.67 ± 21.4 | In the range 15–91 |

| Daily Air Quality Index | Mean value: 43.8 ± 23.8 | In the range 15–114 | Mean value: 30.55 ± 11.81 | In the range 16–69 |

For 1 January–30 April 2020 time period, average daily air temperature has significantly positive correlations with daily mean PBL height (R2 = 0.77) and daily mean wind speed (R2 = 0.26) and negative correlations with daily mean relative humidity (R2 = −0.64). However, relative humidity had significant negative correlations with Planetary Boundary Layer(R2 = −0.61), wind speed (R2 = −0.31) and Air Quality Index (R2 = −0.39). Air Quality Index is negatively correlated with PBL (R2 = −0.39), and daily mean wind speed (R2 = −0.36) and positive correlated with daily mean air humidity (R2 = 0.34).

Table 3 summarizes the Pearson coefficients descriptive statistics of COVID-19 Milan cases (Total confirmed, Daily New and Total Deaths) and daily average air surface levels of PM2.5, PM10, daily maxima PM10 concentrations and Air Quality Index.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients between COVID-19 Milan cases and particle matter concentrations and air quality.

| Time period: 1 January–30 April 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 number cases | Daily average PM2.5 (μg/m3) | Daily average PM10 (μg/m3) | Daily maxima PM10 (μg/m3) | Air Quality Index |

| Total cases | −0.39 | −0.30 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Daily New cases | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| Total deaths | −0.53 | −0.49 | −0.23 | −0.25 |

Table 4 describes the Pearson coefficients descriptive statistics of COVID-19 Milan cases (Total confirmed, Daily New and Total Deaths) and daily average climate variables (Planetary Boundary Layer, Air Temperature, Relative Humidity and wind speeds).

Table 4.

Pearson correlation coefficients between climate variables and air surface particulate matter concentrations and air quality.

| Time period: 1 January–30 April 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily average climate variable | Daily average PM2.5 (μg/m3) | Daily average PM10 (μg/m3) | Daily maxima PM10 (μg/m3) | Air Quality Index |

| Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL) (m) | −058 | −0.59 | −0.33 | −0.39 |

| Air temperature (T) (°C) | −0.54 | −0.57 | −0.36 | −0.39 |

| Relative humidity (RH) ( %) | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.34 |

| Wind speed intensity (km/h) | −0.32 | −0.50 | −0.41 | −0.36 |

Table 5 presents the Pearson coefficients descriptive statistics between daily average climate variables and air surface particulate matter concentrations together with air quality in Milan metropolitan region.

Table 5.

Pearson correlation coefficients between COVID-19 Milan cases and daily average climate variables.

| Time period: January–April 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 number cases | Planetary Boundary Layer(PBL) | Air temp. T (°C) | Relative humidity RH(%) | Wind speed (km/h) |

| Total cases | 0.79 | 0.67 | −0.47 | −0.02 |

| Daily New cases | 0.36 | 0.24 | −0.32 | −0.14 |

| Total deaths | 0.82 | 0.73 | −0.53 | 0.15 |

3.2. Impact of particulate matter PM2.5, PM10 and air quality on COVID-19

Milan in Po valley basin, known hotspot for atmospheric pollution at the continental scale with PM2.5 and PM10 mass concentrations often above the European Community admitted limit values, has a complex morphological structure not allowing air pollutants dispersion. In spite of Air Quality Standards limits established by EC (European Community) (50 μg/m3 for daily average PM10 and 25 μg/m3 for one year average PM2.5 concentrations) in the open atmosphere during investigated period in Milan metropolitan area have been recorded very high PM concentrations before lockdown due to COVID-19, as well as reduced values but also beyond the admitted thresholds for particle matter in both size fractions.

This study found that during the 1 January–30 April 2020 investigated period for the Milan metropolitan region, very high values of both daily mean air surface concentrations of PM2.5 (87.1 ± 39.6 μg/m3), placed in the range of 30–189 μg/m3, as well as for daily average air surface concentrations of PM10 (35.9 ± 18.5 μg/m3), in the range of 8–100 μg/m3 have been recorded. These values for particulate matter exceeded the 2010 EC target value for annual PM2.5 mean concentration (25 μg/m3) at more urban background sites and the PM10 annual limit value of 40 μg/m3. Therefore, the PM2.5 directive is more stringent for urban background sites like for Milan, while PM10 directives were more stringent for kerbside sites.

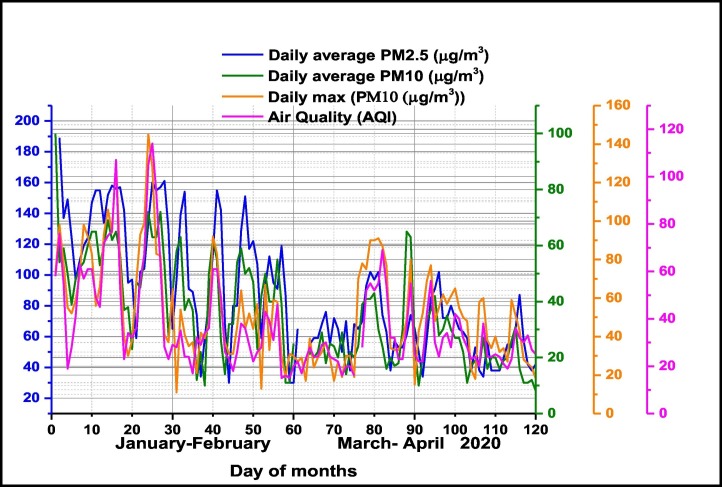

To analyze short- and medium-term effects of air pollution on fast virus diffusion, two time windows (1 January–29 February and 1 March–30 April), also have been considered for Milan city. Due to COVID-19 pandemic event, starting with end of February 2020 lockdown, our study revealed different concentrations levels for PM2.5 and PM10 corresponding to pre-pandemic period (January–February) and beyond lockdown (March–April) 2020 as can be seen in Table 2.

The results provided by this study are in good accordance with previous similar air pollution investigations (Fattorini and Regoli, 2020; Sandrini et al., 2014).

Milan in Po valley basin, known hotspot for atmospheric pollution at the continental scale with PM2.5 and PM10 mass concentrations often above the European Community admitted limit values, has a complex morphological structure not allowing air pollutants dispersion. The atmospheric stagnant conditions and low wind speeds of the valley basin promote the formation of strong vertical PM gradients and accumulation in the lower troposphere, the levels of pollution at ground being very high, especially during haze or fog events (Bigi and Ghermandi, 2014). Po Valley which is a known hotspot for atmospheric pollution at the continental scale with PM10 and PM2.5 mass concentrations often above the EC limit values (Perrone et al., 2012). In such conditions, PM concentrations reach very high values even far from the direct source of the cities (Perrone et al., 2014).

In good accordance with scientific literature (Yadav et al., 2016; Zoran et al., 2014; Penache and Zoran, 2019a; Penache and Zoran, 2019b), daily average ground level ozone concentrations at the ground level were negative correlated with daily average concentrations in the air of particulate matter PM2.5 (R2 = −0.64) and PM10 (R2 = −0.62), as well as with daily maxima PM10 (R2 = −0.34), as PM would significantly reflect the sunlight radiation and retard the photochemical reaction forming ozone. During 1 January–30 April 2020, O3 daily average ground level concentrations have recorded values in the range of 2–57 μg/m3 with a mean value of 26.47 ± 15.55 μg/m3, while another main gaseous pollutant nitrogen dioxide (NO2) had a mean value of 27.86 ± 10.37 μg/m3, in the range of 4–57 μg/m3 Also, statistical Pearson correlation coefficients show a positive relationship of PM with NO2 ground level concentrations as follows: R2 = 0.44 for daily average PM2.5, R2 = 0.47 for daily average PM10, and R2 = 0.30 for daily maxima PM10 concentrations.

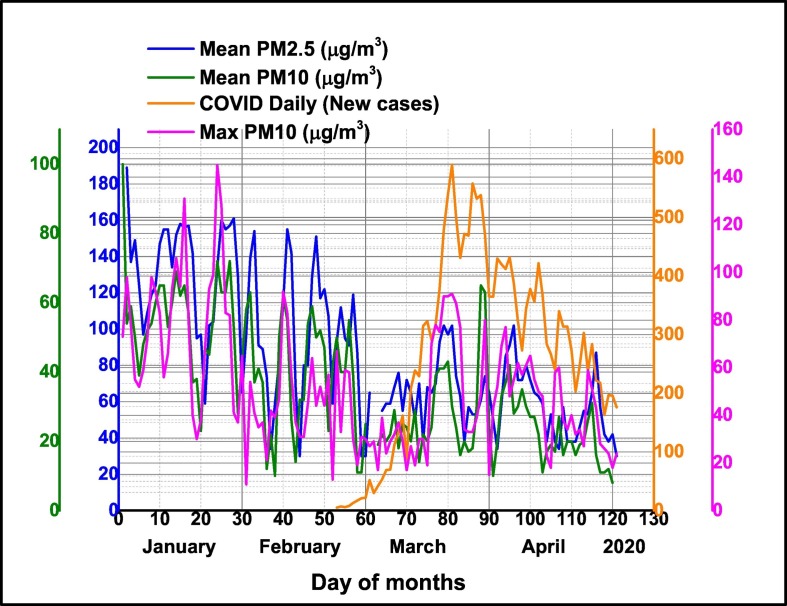

The temporal pattern of daily average particle matter PM2.5 and PM10 together daily maxima PM10 concentrations and Air Quality Index (AQI) in Milan pre-lockdown period (January–February 2020) and during lockdown period (March–April 2020) are presented in Fig. 4 . The results have shown that during lockdown air quality was significantly improved. Among the selected pollutants, concentrations of daily average PM10 and PM2.5 were significantly reduced in comparison with pre-lockdown period, namely with 45% for PM2.5 and 47% for PM10 respectively. The same conclusion is supported by the recorded daily maximum PM10 values which have been reduced by 24%. Air Quality Index was improved by 30% of pre-lockdown values. As in other worldwide countries, a lockdown response to COVID-19, industrial and general economic activity in Milan have been reduced with a high impact on tropospheric and ground level pollution with particulate matter in different size fractions and gaseous pollutants, improving air quality.

Fig. 4.

Temporal distribution of daily average particle matter PM2.5 and PM10 together daily maxima PM10 concentrations and Air Quality Index (AQI) in Milan pre-lockdown period (January–February 2020) and during lockdown period (March–April 2020).

According with scientific literature in the field (D. Wang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; T. Wang et al., 2020; Cohen and Kupferschmidt, 2020), the presence of existing comorbidities associated possible with patients' age, immunity system, sex, genetic and nutritional status, etc., appeared to be important factors for the aetiology and severity of Covid-19 symptoms in Milan, Lombardy region. The role of pre-existing immune disorders induced by long- term or short-term exposure to high air surface levels of particle matter PM10 and PM2.5 atmospheric pollution contributes to the impressive SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Milan and Lombardy province (Conticini et al., 2020; Dutheil et al., 2020; Fattorini and Regoli, 2020).

Our study found positive correlations between all confirmed COVID-19 Daily New cases in Milan and air pollution with particulate matter as follows, namely: with daily maxima PM10 (R2 = 0.51), daily average surface air PM2.5 (R2 = 0.25), daily AQI (R2 = 4.35) as can be seen in Table 3.

Temporal pattern of daily average particle matter PM2.5 and PM10 together daily maxima PM10 concentrations and confirmed COVID-19 Daily New cases in Milan is presented in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Temporal pattern of daily average particle matter PM2.5 and PM10 together daily maxima PM10 concentrations and confirmed COVID-19 Daily New cases in Milan.

High rate of confirmed COVID-19 Daily New cases in Milan, are well correlated with particulate matter air pollution to high levels of particulate matter and other air pollutants, which exceeded admitted EC limits and might be attributed to bronchial hyper-reactivity and the inflammation resulting from long-term exposure during previous years. Our results thus, support the hypothesis that exposure to increasing levels of PM air pollution in the COVID-19 pre-lockdown (January–February 2020) as well as during lockdown period might render Milan inhabitants more susceptible to viral infection, particularly relevant existing vulnerabilities and comorbidities. Several investigations are in agreement with our findings, highlighting the relevance of short- medium- to long term exposure to PM10 and PM2.5 as an essential factor for viral infections (Carugno et al., 2018; Ma et al., 2020; Poole, 2020; Wu et al., 2020).

3.3. Influences of Planetary Boundary Layer and climate parameters on particulate matter PM and COVID-19 cases

Planetary (Atmospheric) Boundary Layer characteristics play a crucial role in the dispersion and dilution of air pollutants near the earth's surface. During days with higher average PBL height are recorded lower pollutant concentrations near the ground. Higher average PBL heights and enhanced convective activities allow the dilution of pollutants, followed by decreasing of their concentrations near the ground, while in days with lower PBL heights air pollutants get trapped near the ground (Zoran et al., 2014). Shallow PBL heights recoded in Milan metropolitan region during January–February months 2020 can be partially responsible for several pollution episodes and increase of inhabitant's human respiratory vulnerability to viral COVID-19 infection. Temporal patterns of daily mean values of PBL recorded in Milan large town during January–April 2020 were negative correlated with daily surface air mean concentrations of particulate matter namely: PM2.5 (R2 = −0.58), PM10 (R2 = −0.59), with daily PM10 maxima (R2 = −0.33) as well as with Air Quality Index (R2 = −0.39) as can be seen in Table 4. The formation of severe haze or fog episodes during inversion conditions, which reflects synergetic effects caused by interactions between regional air masses transport, local emissions, and atmospheric physicochemical processes will have also a strong negative impact on human respiratory system and health. Meteorological variables such as temperature, relative humidity (RH), and wind speed and direction could impact the formation and dispersion of pollutants in the ambient air (Qi et al., 2020; Ahmadi et al., 2020; Bashir et al., 2020; Xieand Zhu, 2020). Analysis of the Pearson correlation coefficients show that daily mean surface air PM2.5 and PM10 together daily maxima PM10 concentrations and daily Air Quality Index in Milan were significantly positive correlated with daily average humidity, and negative correlated with daily average temperature, wind speed, and Planetary Boundary Layer.

Infections caused by airborne pathogens like viruses and bacteria are dependant on several factors: the emission rate of pathogens, function of pathogen availability and the aerosolization rate; meteorological (wind speed intensity, wind direction, solar radiation, atmospheric stability, wet or dry deposition) effects; inactivation of pathogenic bioaerosols like viruses or bacteria that is a function of time or meteorological conditions, such as temperature and humidity, and may be in the time range of minutes to hours or days; the amount of inhaled pathogens, with breathing rate, lung volume, and particle size being important factors; the host's health response as a function of inhaled dose (Weber and Stilianakis, 2008; Tang et al., 2010) All these factors can affect the degree of viability and spread of contagious viruses like COVID-19.

Viral aerosol diffusion considers the possibility that fine virus particles, called droplet nuclei, to remain airborne for prolonged periods. This viral aerosol transmission involves particles of diameter < 5 μm (Li et al., 2004). For corona virus, the airborne transmission has not yet been clearly established but there is growing evidence for aerosol-driven infection. Production of infectious droplets and subsequent spread to surrounding environment is determined by generation and annihilation processes and may be affected by many variables such as air temperature, relative humidity, air mass concentrations, wind intensity, etc. Inactivation of pathogenic bioaerosols like viruses or bacteria is expressed as a function of time or meteorological conditions, such as temperature and humidity, may be in the time range of minutes to hours or days, while spores are generally highly persistent (Bowers et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014; Harrison et al., 2005; Yang and Marr, 2012; Minhaz Ud-Dean, 2010) .

Statistical analysis shows that daily mean ground level PM10 concentrations in Milan were negative correlated with daily average temperature (R2 = −0.57) and Planetary Boundary Layer.

(R2 = −0.59), in good accordance with other studies (Tosepu et al., 2020) and positive correlated with daily average relative humidity and Air Quality Index (R2 = 0.65). As higher humidity levels are associated with large cloud cover and atmospheric instability, PM are depleted by wet deposition on water droplets (Wu et al., 2020; Dalziel et al., 2018). Furthermore, air temperature also contributes towards the transmission of the virus (Chen et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020) suggested that humidity and temperature will play an important role in mortality rate from COVID-19 as climate indicators and temperature correlate with the spread of COVID-19 (Poole, 2020). Pearson correlation coefficient between daily mean ground level fine particulate matter PM2.5 concentrations in Milan were also negative correlated with daily average air temperature (R2 = −0.54) and Planetary Boundary Layer (R2 = −0.58) and positive correlated with daily average relative humidity (R2 = 0.59) and Air Quality Index (R2 = 0.60).

Is increasingly recognized that both indoor as well as outdoor relative humidity is an important factor in determining respiratory diseases severity (Xie and Zhu, 2020). Decreased levels of humidity are associated with decreased severity of pulmonary diseases while increased levels are associated with higher severity aspects of respiratory tract. Anyway this study has found that outdoor daily average relative humidity in Milan during January–April investigated period was positive correlated with particulate matter PM2.5 (R2 = 0.59) and PM10 concentrations (R2 = 0.64).

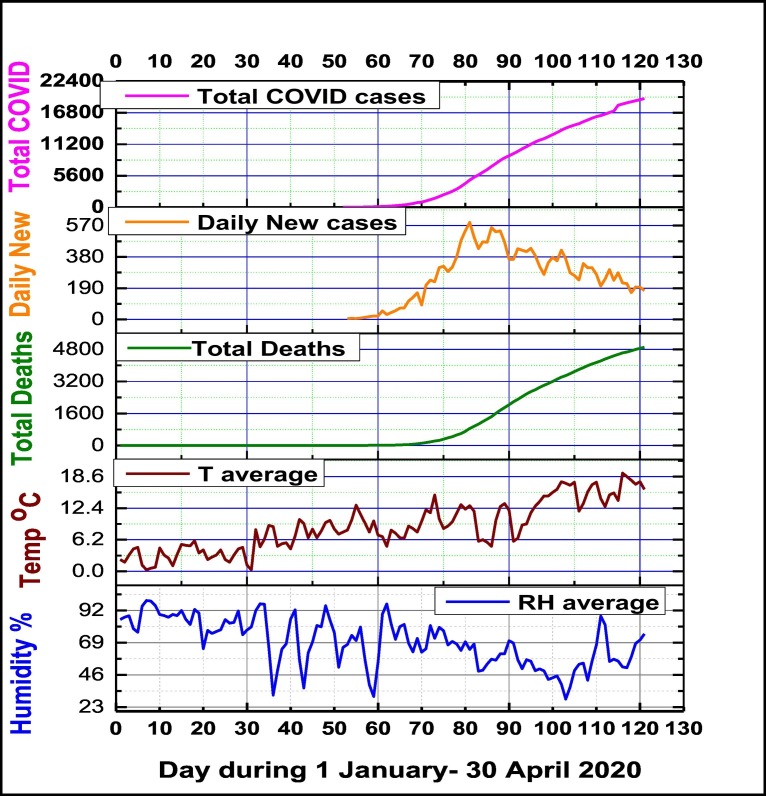

In our research daily mean recorded average relative humidity was 69.42 ± 17.06% and its variation was in the range of 28.7–99.1%. During investigated period air relative humidity in Milan was inversely correlated with all confirmed COVID-19 cases (Total Deaths, Daily New and Total numbers). As can be seen from Table 5, the Pearson coefficients descriptive statistics between are relative humidity and COVID-19 Milan cases were as follows: for Total COVID-19 cases (R2 = −0.47), (R2 = −0.32) for Daily New cases and (R2 = −0.53) for Total Deaths cases.

Several papers had provided experimental evidence that transmission of some viral infectious diseases via the airborne route is very important (Marr et al., 2019; Vejerano and Marr, 2018). Furthermore was evidenced that there is a relationship between incidence or transmission and humidity, finding that the viruses in droplets and aerosols survives well at low relative humidity below approximately 50%, and opposite for high levels of humidity. According with present literature in the field of virology and epidemiology, this research found that relative humidity is an essential climate variable in understanding viral infectivity and transmission, which is negatively correlated with all COVID-19 cases registered in Milan, as Fig. 6 is showing.

Fig. 6.

Temporal distribution of daily mean climate variables (relative humidity and air temperature) and confirmed COVID-19 Total Deaths, Daily New cases and Total cases.

This result supports the conclusion that air daily mean relative humidity is an essential climate factor for COVID-19 virus viability, dry weather conditions being favorable for COVID-19 viral infection spreading, while humid weather conditions have an opposite effect. Several studies confirmed that air low humidity levels might be an important risk factor for respiratory infection diseases, low-humidity levels can cause a large increase in mortality rates (Barreca, 2012; Davis et al., 2016; Fallah and Mayvaneh, 2016; Tan et al., 2005; Sajadi et al., 2020). A possible explanation might be available for COVI-19, as breathing dry air could induce epithelial damage of respiratory tract or reduction of mucociliary clearance, and an increased susceptibility to respiratory virus infection. Also, the formation of small droplet nuclei is essential to viral infection transmission, while exhaled respiratory droplets settle very fast at air high humidity levels. Fig. 6 shows also a positive relationship between daily mean air temperature and confirmed COVID-19 Total Deaths, Daily New cases and Total cases, Pearson correlation coefficients being respectively of R2 = 0.73, R2 = 0.24 and R2 = 0.67. This result supports hypothesis that warm weather will not stop COVID diffusion cases.

The high rate of total COVID-19 cases registered in the metropolitan area of Milan possible attributed to bronchial hyperreactivity and the inflammation resulting from exposure to pollutants may be of consequence to the immune disorders through several pathways. Among the climate variables, wind speed has a weakly inverse relationship (R2 = −0.14) with the confirmed Daily New COVID-19 cases (Table 5).

Mostly during analyzed cold period (January–February) in Milan have been registered some episodes of fog and haze, which favor the air pollutants accumulation at the surface, having negative impacts on human health (Wu et al., 2020; Tosepu et al., 2020). Another factor that contributed at the high levels of air pollution over investigated time period in Milan was almost lack of precipitations. For 1 January- 30 April analyzed period, the daily average precipitation level was very low(0.12 ± 0.07) mm/day, ranging from (02.1mm/day), therefore washout processes of air pollutants was very weak. The removal efficiency of air pollutants in Milan can be triggered by the main two forcing: wind and precipitation. At lower daily mean precipitation levels and wind speeds the diffusion of this invasive pneumococcal disease might have high rate. Statistical analysis shows that Pearson correlation coefficients between daily mean ground levels PM in the both size fractions were significant inversely correlated with daily average wind speeds, respectively R2 = −0.50 for PM10, and R2 = −0.32 for PM2.5 concentrations. During 1 January–30 April 2020 investigated period in Milan metropolitan area, the average daily wind speed had a low value, namely 6.7 ± 3.4 km/h, in the range of 2.4–18.8 km/h, the result being associated with almost stability conditions, which favor air pollutants accumulation near the ground. Similar with other findings (Ahmadi et al., 2020; Sundell et al., 2016; Pope et al., 2009; Prabhu and Shridhar, 2019), time series of investigated climate variables in this study demonstrated that a sudden drop in outdoor temperature might activate the COVID-19 epidemic in a temperate climate, and relative humidity will facilitate aerosol spread in dry air. Other weather conditions like winds and atmospheric pressure field can affect the incidence of different respiratory pathogens, suggesting that viral airborne routes of infection may be relevant for these agents.

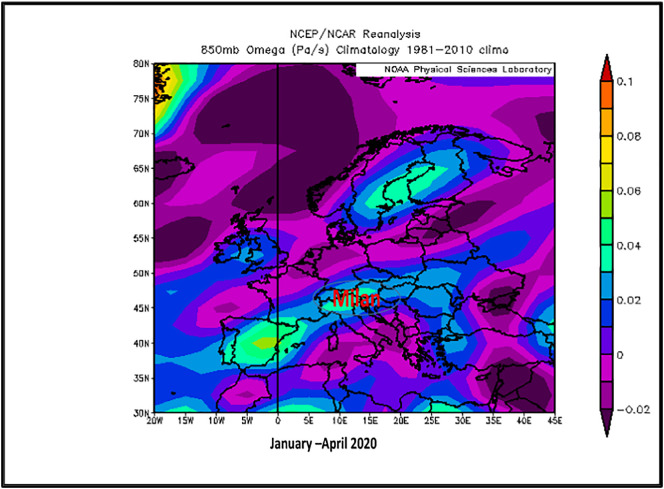

3.4. Atmospheric pressure field, particulate matter and air quality

During 1 January–30 April 2020, the NOAA NCEP/NCAR reanalysis for evaluating the atmospheric capability to disperse air pollutants provided satellite vertical airflows Omega surface charts at 850 mb (~1.5 km above sea level) and 950 mb (~0.762 km above sea level), which recorded downwards airflows described by positive omega values. It means that over Lombardy and Milan region, there was a strong atmospheric inversion, much intensely described by 850 mb map (0.03–0.05 Pa/s) as well as 925 mb map (0.02–0.03 Pa/s) during the January–April period (including pre-lockdown and beyond lockdown COVID-19). This inversion layer acts as a cover and affects the activity of the atmosphere within the atmospheric boundary layer. This observation together with recorded lower levels of PBL having daily mean value of 811.83 ± 553.53 m explains the stagnant conditions, which allowed accumulation of higher levels of PM2.5, PM10 and other air pollutants (both non-viable aerosols as well as viable -bioaerosols including viruses like as coronaviruses, bacteria, fungi, etc.) at the ground surface air, leading to a higher risk of population exposure (Ogen, 2020). NOAA satellite Omega image for Europe (Fig. 7 ) is proving existing atmospheric inversion conditions over Milan region, favorable for stagnant atmospheric stability due to local topography of Milan area. The pre-existing high levels of air pollutants during January–February months can explain the high incidence of people's respiratory diseases, increased susceptibility to new viral infections COVID-19 and high rate of fatalities. Another possible contributor at atmospheric pollution in the area can be attributed to recorded trans-border polluted air masses from neighbourhood regions and countries, as ESA European daily air quality analysis is providing information for South East Europe PM (PM2.5 and PM10) time series data evolution.

Fig. 7.

NOAA satellite atmospheric pressure field Omega chart over Europe during January–April 2020 (inversion conditions over Milan metropolitan area).

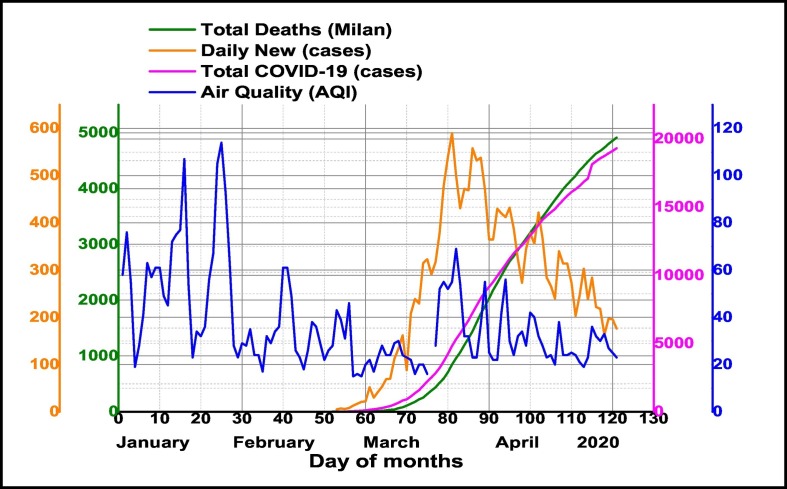

As an important result, our analysis demonstrated the high influence of daily Air Quality Index (AQI) on COVID-19 cases outbreak in Milan (Fig. 8 ). Being a novel pandemic coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) version, it might be ongoing during summer conditions associated with higher temperatures and low humidity levels. Also, this paper might support the possibility as besides indoor diffusion outdoor airborne transmission of the virus to have a great contribution.

Fig. 8.

Temporal distribution of daily Air Quality Index and confirmed COVID-19 cases (Total, Daily New and Total Deaths) in Milan metropolitan region during January–April 2020.

It seems that under specific climate conditions (Bashir et al., 2020), air pollution acts as a carrier of the COVID-19 virus, facilitating its transmission and spreading, allowing its survival in active form with different residence times. Also, urban air pollution imposes an increased vulnerability of the population to respiratory syndromes, even in the absence of microbial causative agents (Wang and Su, 2020; Smets et al., 2016). Association between Milan, with several days of smog and haze, which favor air pollutants accumulation near the ground level in cold and dry winter to spring seasons and the highest number of COVID-19 cases (Total confirmed, Daily New and Total Deaths), thereby is supporting the possibility as the degree of air pollution and local topography together climate conditions may contribute to accelerated diffusion of COVID-19 cases.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we used a comprehensive time series analysis of the key air pollutants particulate matter PM2.5, PM10 and Air Quality Index data together climate and coronavirus data for period 1 January–30 April 2020 in order to provide additional evidence on the possible impacts of surface levels air pollution on fast diffusion effects of SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 in Milan metropolitan city, Lombardy region in Italy. This study evidenced negatively correlation of COVID-19 with relative air humidity, showing that dry air supports viral ongoing diffusion, and positively correlation with air temperature, supporting the hypothesis that warm season will not stop COVID-19 spreading. Also, is known that chronic or short-term exposure to particulate matter PM2.5 or PM10, with possible attachment of different viruses or bacteria has a significant negative impact of the human immune system. These aerosols might be transported deeply into the lungs to reach alveoli, and penetrate multilayer barriers of the respiratory system. At this moment is not clear if this protein “spike” of the new coronavirus COVID-19 is involved through mechanisms of attachment to outdoor and indoor aerosols transmission of the infectious agent from a reservoir to a susceptible host through airborne diffusion. A real understanding of the possible causes of airborne transmission is crucial for development and selecting appropriate and effective control methods in hospitals, and the community in order to develop preventive strategies to handle the viral infection. Also, the findings of this study revealed the importance of future improvement of air quality in the area, according with European Community standards in order to increase people's immunity to severe viral infections like coronaviruses are.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation, Romania, contract nr. 18 PCCDI/2018-VESS-3PIMS, contract nr.19 PFE/2018 and program NUCLEU contract nr. 18N/2019. We are thankful to NOAA/OAR/ESRL PSD, Boulder, Colorado, USA for providing Omega charts.

Editor: Wei Huang

References

- Ahmadi M., Sharifi A., Dorosti S. Investigation of effective climatology parameters on COVID-19 outbreak in Iran. Science of The Total Environment Science of the Total Environment. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadi S., Bouvier N., Wexler A.S., Ristenpart W.D. The coronavirus pandemic and aerosols: does COVID-19 transmit via expiratory particles? Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020;54(6):635–638. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2020.1749229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballabio D., Bolzacchini E., Camatini M.C. Particle size, chemical composition, seasons of the year and urban, rural or remote site origins as determinants of biological effects of particulate matter on pulmonary cells. Environ. Pollut. 2013;176:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreca A.I. Climate change, humidity, and mortality in the United States. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2012;63(1):19–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jeem.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir M.F., Ma B., Bilal Komal B., Bashir M.A., Tan Duojiao, Bashir M. Correlation between climate indicators and COVID-19 pandemic in New York, USA. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138835. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigi A., Ghermandi G. Long-term trend and variability of atmospheric PM10 concentration in the Po Valley. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2014;14:4895–4907. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch B.J., van der Zee R., de Haan C.A.M., Rottier P.J.M. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. J. Virol. 2003 doi: 10.1128/jvi.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers R.M., Clements N., Emerson J.B., Wiedinmyer C., Hannigan M.P., Fierer N. Seasonal variability in bacterial and fungal diversity of the near-surface atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:12097–12106. doi: 10.1021/es402970s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C., Jiang W., Wang B., Fang J., Lang J., Tian G., Jiang J., Zhu T. Inhalable microorganisms in Beijing’s PM2.5 and PM10 pollutants during a severe smog event. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;48(3):1499–1507. doi: 10.1021/es4048472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carugno M., Dentali F., Mathieu G., Fontanella A. PM10 exposure is associated with increased hospitalizations for respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis among infants in Lombardy, Italy. Environ. Res. 2018;166:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y., Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507–513. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J., Kupferschmidt K. Countries test tactics in “war” against COVID-19. Science. 2020;367(6484):1287–1288. doi: 10.1126/science.367.6484.1287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conticini E., Frediani B., Caro D. Can atmospheric pollution be considered a co-factor in extremely high level of SARS-CoV-2 lethality in Northern Italy? Environ. Pollut. 2020:114465. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalziel B.D., Kissler S., Gog J.R., Viboud C., Bjornstad O.N., Metcalf C.J.E., Grenfell B.T. Urbanization and humidity shape the intensity of influenza epidemics in U.S. cities. Science. 2018;362(6410):75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.aat6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis R.E., Dougherty E., McArthur C., Huang Q.S., Baker M.G. Cold, dry air is associated with influenza and pneumonia mortality in Auckland, New Zealand. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses. 2016;10(4):310–313. doi: 10.1111/irv.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q., Ou C., Shen Y.-M., Xiang Y., Li Y. Health effects of physical activity as predicted by particle deposition in the human respiratory tract. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;65720:819–826. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil F., Baker J.S., Navel V. COVID-19 as a factor influencing air pollution? Environ. Pollut. 2020;263 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallah G.G., Mayvaneh F. Effect of air temperature and universal thermal climate index on respiratory diseases mortality in Mashhad, Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2016;19(9):618–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattorini D., Regoli F. Role of the chronic air pollution levels in the Covid-19 outbreak risk in Italy. Environ. Pollut. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S., Gao D., Liao F., Zhou F., Wang X. The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2016;128(June 2016):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Miao Y., Zhang Y. The climatology of Planetary Boundary Layer height in China derived from radiosonde and reanalysis data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016;16(20):13309–13319. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison R.M., Jones A.M., Biggins P.D.E., Pomeroy N., Cox C.S., Kidd S.P. Climate factors influencing bacterial count in background air samples. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2005;49:167–178. doi: 10.1007/s00484-004-0225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen N.A.H., Hoek G., Simic-Lawson M., Fisher P., van Bree L., ten Brink H. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119(12):691–1699. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A.M., Harrison R.M. The effects of meteorological factors on atmospheric bioaerosol concentrations — a review. Sci. Total Environ. 2004;326(1–3):151–180. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly F.J., Fussell J.C. Air pollution and airway disease. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:1059–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M.F., Hamid A.H., Bari M.A., Tajudin A.B., Latif M.T. Airborne particles in the city center of Kuala Lumpur: origin, potential driving factors, and deposition flux in human respiratory airways. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;650(Part 1):1195–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney P.L., Thurston G.D., Raizenne M. The effects of ambient ozone on lung function in children: a reanalysis of six summer camp studies. Environ. Health Perspect. 1996;104:170–174. doi: 10.1289/ehp.96104170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulle T.J., Sauder L.R., Hebel J.R., Chatham M.D. Ozone response relationships in healthy nonsmokers. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1985;132:36–41. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Huang X., Yu I.T.S., Wong I.T.S., Qian H. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Indoor Air. 2004;15:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Zhou Q., Yang X., Li G., Zhang J., Zhou X., Jiang W. Cytotoxicity of the soluble and insoluble fractions of atmospheric fine particulate matter. J. Environ. Sci. 2020;91:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhin E., Holme J.A., Gualtieri M., Camatini M., Øvrevik J. Milan winter fine particulate matter (PM2.5) induces IL-6 and IL-8 synthesis in human bronchial BEAS-2B cells, but specifically impairs IL-8 release. Toxicol. in Vitro. 2018;52:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2018.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C., Liu X., Jia Z. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H., Stratton C.W., Tang Y.-W. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92(4):401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Zhao Y., Liu J., He X., Wang B., Fu S., Yan J., Niu J., Zhou J., Luo B. Effects of temperature variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724:138226. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138226. Allergy 41, 1059–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marr L.C., Tang J.W., Van Mullekom J., Lakdawala S.S. Mechanistic insights into the effect of humidity on airborne influenza virus survival, transmission and incidence. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2019;16(150) doi: 10.1098/rsif.2018.0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell W.F., Horstman D.H., Hazucha M.J. Pulmonary effects of ozone exposure during exercise: dose–response characteristics. J. Appl. Physiol. 1983;54:1345–1352. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.54.5.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P., McAuley D.F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R.S., Manson J.J. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhaz Ud-Dean S.M. Structural explanation for the effect of humidity on persistence of airborne virus: seasonality of influenza. J. Theor. Biol. 2010;264:822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavizadeh L., Ghasemi S. Genotype and phenotype of COVID-19: their roles in pathogenesis. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiura H., Lintona N.M., Akhmetzhanov A.R. Serial interval of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020;93:284–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogen Y. Assessing nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels as a contributing factor to coronavirus (COVID-19) fatality. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;726 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penache M.C., Zoran M. Temporal patterns of surface ozone levels in relation with radon (222Rn) and air quality. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2019;2075:120021. doi: 10.1063/1.5091279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penache M.C., Zoran M. Seasonal trends of surface carbon monoxide concentrations in relation with air quality. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2019;2075:130007. doi: 10.1063/1.5091292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone M.G., Larsen B.R., Ferrero L., Sangiorgi G., De Gennaro G., Udisti R., Zangrando R., Gambaro A., Bolzacchini E. Sources of high PM2.5 concentrations in Milan, Northern Italy: molecular marker data and CMB modelling. Sci. Total Environ. 2012;414:343–355. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone M.G., Gualtieri M., Consonni V., Ferrero L., Sangiorgi G.M.L., Longhin E.M., Sandrini S., Fuzzi S., Piazzalunga A., Prati P., Bonasoni P., Cavalli F., Bove M.C. Spatial and seasonal variability of carbonaceous aerosol across Italy. Atmos. Environ. 2014;99:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J.M., Avol E., Gauderman W.J. A study of twelve Southern California communities with differing levels and types of air pollution. II: effects on pulmonary function. J Respir Crit.Care Med. 1999;159:768–775. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9804144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole L. Causality, and Forecastabililty 3-15–2020. 2020. Seasonal influences on the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID19), causality, and forecastabililty (3-15-2020) (March 15, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Pope C.A., Ezzati M., Dockery D.W. Fine-particulate air pollution and life expectancy in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:376–386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0805646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potukuchi S., Wexler A.S. Identifying solid–aqueous-phase transitions in atmospheric aerosols. II. Acidic solutions. Atmos. Environ. 1995;29:3357–3364. [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu V., Shridhar V. Investigation of potential sources, transport pathway, and health risks associated with respirable suspended particulate matter in Dehradun city, situated in the foothills of the Himalayas. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2019;10:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2018.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi H., Xiao S., Shi R., Ward M., Chen Y., Tu W., Su Q., Wang W., Wang X., Zhang Z. COVID-19 transmission in Mainland China is associated with temperature and humidity: a time-series analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivellese F., Prediletto E. ACE2 at the centre of COVID-19 from paucisymptomatic infections to severe pneumonia. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano S., Perrone M.R., Becagli S., Pietrogrande M.C., Russo M., Caricato R., Lionetto M.G. Ecotoxicity, genotoxicity, and oxidative potential tests of atmospheric PM10 particles. Atmos. Environ. 2020;221 [Google Scholar]

- Sajadi M.M., Habibzadeh P., Vintzileos A., Shokouhi S., Miralles-Wilhelm F., Amoroso A. 2020. Temperature and Latitude Analysis to Predict Potential Spread and Seasonality for COVID-19. (Available at SSRN 3550308) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandrini S., Fuzzi S., Piazzalunga A., Prati P., Bonasoni P., Cavalli F., Bove M.C. Spatial and seasonal variability of carbonaceous aerosol across Italy. Atmos. Environ. 2014;99:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2014.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seposo X., Ueda K., Sugata S., Yoshino A., Takami A. Short-term effects of air pollution on daily single- and co-morbidity cardiorespiratory outpatient visits. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang J., Ye G., Shi K., Wan Y., Luo C., Aihara H. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shereen A. COVID-19 infection: origin, transmission, and characteristics of human coronaviruses. J. Adv. Res. 2020;24:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jare.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi P., Dong Y., Yan H. Impact of temperature on the dynamics of the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728:138890. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smets W., Moretti S., Denys S., Lebeer S. Airborne bacteria in the atmosphere: presence, purpose, and potential. Atmos. Environ. 2016;139:214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama J.T., Ueda K., Seposo X.T., Nakashima A., Kinoshita M., Matsumoto H. Health effects of PM2.5 sources on children’s allergic and respiratory symptoms in Fukuoka. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;709:136023. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.136023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell N., Andersson L.M., Brittain-Long R., Lindh M., Westin J. A four year seasonal survey of the relationship between outdoor climate and epidemiology of viral respiratory tract infections in a temperate climate. J. Clin. Virol. 2016;84:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tager I.B., Balmes J., Lurmann F., Ngo L., Alcorn S., Künzli N. Chronic exposure to ambient ozone and lung function in young adults. Epidemiology. 2005;16(6):751–759. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000183166.68809.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan J., Mu L., Huang J., Yu S., Chen B., Yin J. An initial investigation of the association between the SARS outbreak and weather: with the view of the environmental temperature and its variation. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2005;59:186–192. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.W. Comparison of the incidence of influenza in relation to climate factors during 2000 – 2007 in five countries. J. Med. Virol. 2010;82:1958–1965. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tisoncik J.R., Korth M.J., Simmons C.P., Farrar J., Martin T.R., Katze M.G. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76:16–32. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosepu R., Gunawan J., Effendy D.S. Correlation between weather and Covid-19 pandemic in Jakarta, Indonesia. Sci. Total Environ. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vejerano E.P., Marr L.C. Physico-chemical characteristics of evaporating respiratory fluid droplets. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2018;15 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2017.0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y., Shang J., Sun S. Molecular mechanism for antibody-dependent-enhancement coronavirus entry. J. Virol. 2020;94(5) doi: 10.1128/JVI.02015.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Su M. A preliminary assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on environment – a case study of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Associations between daily outpatient visits for respiratory diseases and ambient 428 fine particulate matter and ozone levels in Shanghai, China. Environ. Pollut. 2018;240:754–763. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., Zhu F., Liu X., Zhang J.…Peng Z. Clinical Characteristics of 138 Hospitalized Patients With 2019 Novel Coronavirus–Infected Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Du Z., Zhu F., Cao Z., An Y., Gao Y., Jiang B. Comorbidities and multi-organ injuries in the treatment of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10228):e52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30558-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Wang Y., Chen Y., Qin Q. Unique epidemiological and clinical features of the emerging 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) implicate special control measures. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:568–576. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber T.P., Stilianakis N.I. Inactivation of Influenza A viruses in the environment and modes of transmission: a critical review. J. Inf. Secur. 2008;57:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 51. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situationreports

- Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Goldsmith J.A., Hsieh C.-L., Abiona O. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science (80- ) 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C.F., Shen F.H., Li Y.R., Tsao T.M., Tsai M.J., Chen C.C., Hwang et.al. Association of short-term exposure to fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide with acute cardiovascular effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;569–570:300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Xia J., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., Zhang L., Zhou X., Du C. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. Published online March 13, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J., Zhu Y. Association between ambient temperature and COVID-19 infection in 122 cities from China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z., Li Y., Lu R., Li W., Fan C., Liu P., Wang W. Characteristics of total airborne microbes at various air quality levels. J. Aerosol Sci. 2018;116:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Xu H., Zhong L., Deng J., Peng J., Dan H., Zeng X. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019-nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J. Oral. Sci. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav R., Sahu L.K., Beig G., Jaaffrey S.N.A. Role of longrange transport and local meteorology in seasonal variation of surface ozone and its precursors at an urban site in India. Atmos.Environ. 2016;176–177:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Marr L.C. Mechanisms by which ambient humidity may affect viruses in aerosols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:6781–6788. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01658-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Peng F., Wang R., Guana K., Jiang T., Xue G., Suna J., Chang C. The deadly coronaviruses: the 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020;109:102434. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki K., Brito J.M., Silva L.F., Lino-dos-Santos-Franco A., Frias D.P. The effects of particulate matter on inflammation of respiratory system: differences between male and female. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;586:284–295. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Aarnink A.J.A., De Jong M.C.M., Groot Koerkamp P.W.G. Airborne microorganisms from livestock production systems and their relation to dust. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014;44:1071–1128. doi: 10.1080/10643389.2012.746064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M., Dida M.R., Zoran A.T., Zoran L.F., Dida A. Outdoor 222Radon concentrations monitoring in relation with particulate matter levels and possible health effects. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2013;296(3):1179–1192, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M., Dida M.R., Savastru R., Savastru D., Dida A., Ionescu O. Ground level ozone (O3) associated with radon (222Rn) and particulate matter (PM) concentrations and adverse health effects. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2014;300:729–746. [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M., Savastru D., Dida A. Assessing urban air quality and its relation with radon (222Rn) J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10967-015-4681-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zoran M., Savastru R., Savastru D., Penache M.C. Temporal trends of carbon monoxide (CO) and radon (222Rn) tracers of urban air pollution. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2019;320:55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y., Jin C., Su Y., Li J., Zhu B. Water soluble and insoluble components of urban PM2.5 and their cytotoxic effects on epithelial cells (A549) in vitro. Environ. Pollut. 2016;212:627–635. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zowalaty M.E., Järhult J. From SARS to COVID-19: a previously unknown SARS-related coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) of pandemic potential infecting humans – call for a One Health approach. One Health. 2020;9:100124. doi: 10.1016/j.onehlt.2020.100124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]