Abstract

Objective:

Guided by cognitive theory, this study tested an explanatory model for adolescents’ beliefs, feelings, and healthy lifestyle behaviors and sex differences in these relationships.

Methods:

Structural equation modeling evaluated cross-sectional data from a healthy lifestyle program from 779 adolescents 14 through 17 years old.

Results:

Theoretical relationships among thoughts, feelings, and behaviors were confirmed and sex differences identified. Thoughts had a direct effect on feelings and an indirect effect through feelings on healthy behaviors for both sexes. A direct effect from thoughts to behaviors existed for males only.

Discussion:

Findings provide strong support for the thinking–feeling–behaving triangle for adolescents. To promote healthy lifestyle behaviors in adolescents, interventions should in-corporate cognitive behavioral skills–building activities, strengthening healthy lifestyle beliefs, and enhancing positive health behaviors.

Keywords: Adolescent physical and mental health, healthy lifestyle behaviors, cognitive behavior skills, path analysis

BACKGROUND

Understanding factors that contribute to healthy lifestyle behaviors in adolescents is critical to the development of interventions needed to promote positive behaviors that can prevent negative physical and mental health outcomes, which may have lifelong implications. Cognitive theory (CT; Beck, 1979) is a model linking a person’s thoughts to emotions and behaviors. The basic premise of CT is that an individual’s emotions and behaviors are, in large part, determined by the way in which he or she thinks and appraises the world (Beck, 2011). Therefore, a person who has negative beliefs tends to have negative emotions and behave in negative ways (Beck, 1979; Lewinsohn, Clarke, Hops, & Andrews, 1990; Skinner, 1960). A form of psychotherapy, cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) builds on CT principles. In CBT, people learn specific skills to identify distorted thinking, modify beliefs, and change behaviors. Negative emotions and behaviors are exacerbated when poor emotional regulation, problem-solving, and assertiveness skills are present.

CBT is recognized as a psychotherapy criterion standard for mild to moderate anxiety or depression (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, 2015). Skills from CBT (e.g., cognitive reframing, goal setting, problem solving, behavior activation) have also been successfully used in behavior change interventions targeting health behaviors in adolescents (Beck, 2011; Hoying, Melnyk, & Arcoleo, 2016; Linardon, Wade, de la Piedad Garcia, & Brennan, 2017; Lock, 2015; Wilfley, Kolko, & Kass, 2011; Winkler, Dörsing, Rief, Shen, & Glombiewski, 2013). Le Grange, Lock, Agras, Bryson, and Jo (2015) implemented a CBT-based intervention for adolescents with an eating disorder that indicated a significant longitudinal reduction in binge/purge behaviors. Winkler et al. (2013) completed a meta-analysis for Internet addiction; CBT-based interventions had a larger effect size for a reduction in screen time and depression compared with other treatments in adults and adolescents.

Although there is a body of growing evidence to support CBT as an effective strategy to target improvements in mental health and healthy lifestyle behaviors in adolescents, less is known about how the relationships among thoughts, feelings, and healthy lifestyle behaviors function in adolescents. Furthermore, inherent developmental differences between adolescent males and females may influence the effects of behavior change interventions. For example, females have been recognized to be at higher risk for anxiety and depression compared with males (Altemus, Sarvaiya, & Epperson, 2014; Avenevoli, Swendsen, He, Burstein, & Merikangas, 2015). Reviews by Haynos and O’Donohue (2012) and Kaisari, Yannakoulia, and Panagiotakos (2013) reported that compared with males, females had slightly more favorable outcomes to interventions to increase healthy lifestyle behaviors. Thus, a basic understanding of cognitive behavioral processes between sexes may inform how behavioral interventions are most likely to succeed (Haynos & O’Donohue, 2012; Melnyk et al., 2013, 2015; Tate, Spruijt-Metz, Pickering, & Pentz, 2015). Scalable interventions to increase healthy lifestyle behaviors should target this population to improve health outcomes during adolescence and into adulthood.

Guided by CT (Figure 1), the objectives of these secondary analyses were to test an explanatory model for the influence of adolescents’ thoughts and feelings on healthy lifestyle behaviors and to investigate whether there are sex differences in these relationships.

FIGURE 1.

The cognitive behavioral therapy model of how thoughts affect feelings and behaviors.

METHODS

Ethics

The institutional review board for The Ohio State University reviewed and approved these secondary analyses. All participating universities and school districts approved the original study.

Participants

Baseline measures from a longitudinal randomized controlled trial titled “Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment (COPE)” were used for this study (Melnyk et al., 2013, 2015). Urban and suburban high school teens (N = 779) from 11 schools in two school districts from the Southwestern United States were included. Adolescents aged 14 through 17 years, primarily fresh-men and sophomores, were recruited and enrolled from their required health education courses. Data were collected from January 2010 through December 2012.

Measures

Healthy lifestyle beliefs scale

Healthy lifestyle beliefs were measured using the Healthy Lifestyles Beliefs scale (Melnyk, 2014; Melnyk & Moldenhauer, 2006). Previous studies show that this scale has acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha equal to .89 (Melnyk et al., 2013). The Healthy Lifestyles Beliefs scale consists of 16 items with Likert-type responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree); higher scores indicate greater healthy lifestyle beliefs. Examples of questions include I am sure I will do what is best to lead a healthy life, I am sure that I will do what is best to keep myself healthy, and I know what to do when things bother or upset me.

Healthy lifestyle perceived difficulty scale

The Healthy Lifestyle Perceived Difficulty scale measures perceived difficulty in engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors. It is a 12-item measure with Likert-type responses ranging from 1 (very hard to do) to 5 (very easy to do); higher scores reflect lower perceived difficulty. Examples of items include How hard is it to exercise regularly? and How hard is it to take the time to help plan and prepare healthy meals? Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .88 (Braet & Van Winckel, 2000).

Beck youth inventories

The Beck Youth Inventories (BYI) for children ages 7 through 18 years was used to measure adolescents’ feelings. The BYI consists of five subscales: Anger, Anxiety, Depression, Self-concept (a scale to evaluate themselves in relation to other people they know), and Disruptive behavior. Each subscale has 20 questions with Likert-type responses ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always), and higher scores are indicative of more negative emotions. Cronbach’s alphas for all subscales were greater than .89 (Melnyk et al., 2013).

Healthy lifestyle behaviors scale

The Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors scale evaluates health behaviors reflective of physical activity, diet, and mental health. This instrument contains 15 items with Likert-type responses ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher scores signifying greater engagement in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Examples include I make healthy food choices, I exercise on a regular basis, I choose water as a beverage instead of a sugared drink at least once a day, I set goals I can accomplish, and I talk about my worries or stress every day. Cronbach’s alpha was .85 (Melnyk et al., 2013).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, version 22.0, and Mplus 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). Latent variables were constructed representing thoughts, feelings, and healthy lifestyle behaviors. The latent variable for Thoughts comprised the Healthy Lifestyle Perceived Difficulty (reverse scored), Healthy Lifestyle Beliefs, and BYI Self-Concept (reverse scored) scales. The latent variable for Feelings was measured by the BYI Depression, Anxiety, and Anger subscales. The Behaviors latent variable included the Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and BYI Disruptive Behaviors scales. The dependent variables were the latent variables for Feelings and Behaviors. Two structural equation models (SEMs) were run. First, a two-group (male, female) SEM with maximum likelihood estimation was specified to test the hypothesized explanatory model for direct and indirect effects of thoughts and feelings on healthy lifestyle behaviors. The second model constrained all parameters to be equal to examine whether the SEM models differed for males and females as evidenced by a decrease in model fit. Statistical significance was set at p less than .10.

RESULTS

The sample was 52% female, and the majority were of Latino ethnicity (68%), followed by White (14%), Black (10%), Asian (4%), and Native American (4%). Most of the sample (76%) reported receiving public assistance. The mean age was 14.7 years (standard deviation = 0.73). The Table presents the descriptive statistics for the observed indicators of the latent variables for thoughts, feelings, and healthy lifestyle behaviors for the whole sample and differences by sex. For the latent variable Thoughts, adolescent males had higher reported beliefs in their ability to engage in healthy lifestyles compared with females. Females also scored lower than males on the Self-concept subscale, yet females perceived lower difficulty engaging in healthy behaviors. For the latent variable Feelings, proportionally females scored higher than males on the Depression and Anger subscales but not the Anxiety subscale. Although the difference for healthy lifestyle behaviors between males and females was not significant, females did have significantly higher reported disruptive behavior.

TABLE.

Descriptive statistics for the observed indicators of the latent variables for thoughts, feelings and behaviors

| Latent variable | Observed variable | Total, mean score (SD) | Males, mean score (SD) | Females, mean score (SD) | Mean difference | p (95% Cl)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thoughts | Healthy lifestyle beliefs | 63.49 (8.94) | 64.41 (8.26) | 62.60 (9.47) | 1.81 | .006 [0.52, 3.08] |

| Healthy lifestyle perceived difficulty | 28.30 (7.94) | 27.13 (7.46) | 29.40 (8.24) | −2.27 | < .0001 [−3.39, −1.15] | |

| BYI self-conceptb | −50.15 (10.22) | −52.39 (9.40) | −48.06 (10.51) | −4.33 | < .0001 [−5.75, −2.91] | |

| Feelings | BYI anxiety | 48.43 (9.99) | 47.50 (8.78) | 49.32 (10.94) | −1.82 | .011 [−3.23, −0.42] |

| BYI depression | 46.55 (9.57) | 45.44 (7.52) | 47.60 (11.08) | −2.16 | .002 [−3.50, −0.83] | |

| BYI anger | 45.83 (9.70) | 43.96 (7.96) | 47.60 (10.81) | −3.64 | < .0001 [−4.99, −2.29] | |

| Behaviors | Healthy lifestyle behaviors | 52.01 (9.34) | 53.22 (9.01) | 50.89 (9.50) | 2.33 | .001 [1.01, 3.66] |

| BYI disruptive behaviors | 47.99 (9.76) | 45.93 (8.32) | 49.94 (10.59) | −4.01 | < .0001 [−5.35, −2.66] |

Note. BYI, Beck Youth Inventories; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation.

p < .05 considered statistically significant.

Reverse scored.

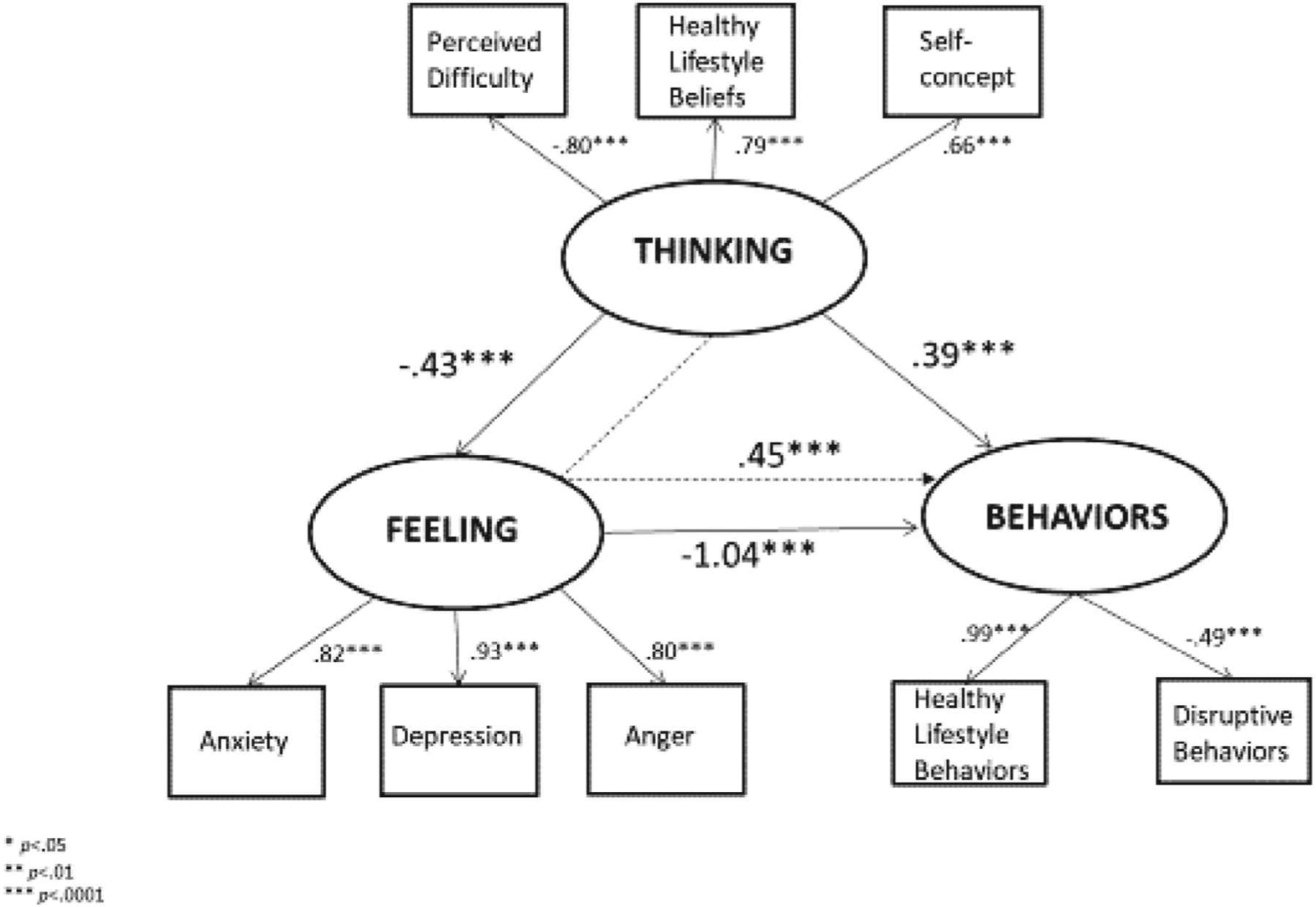

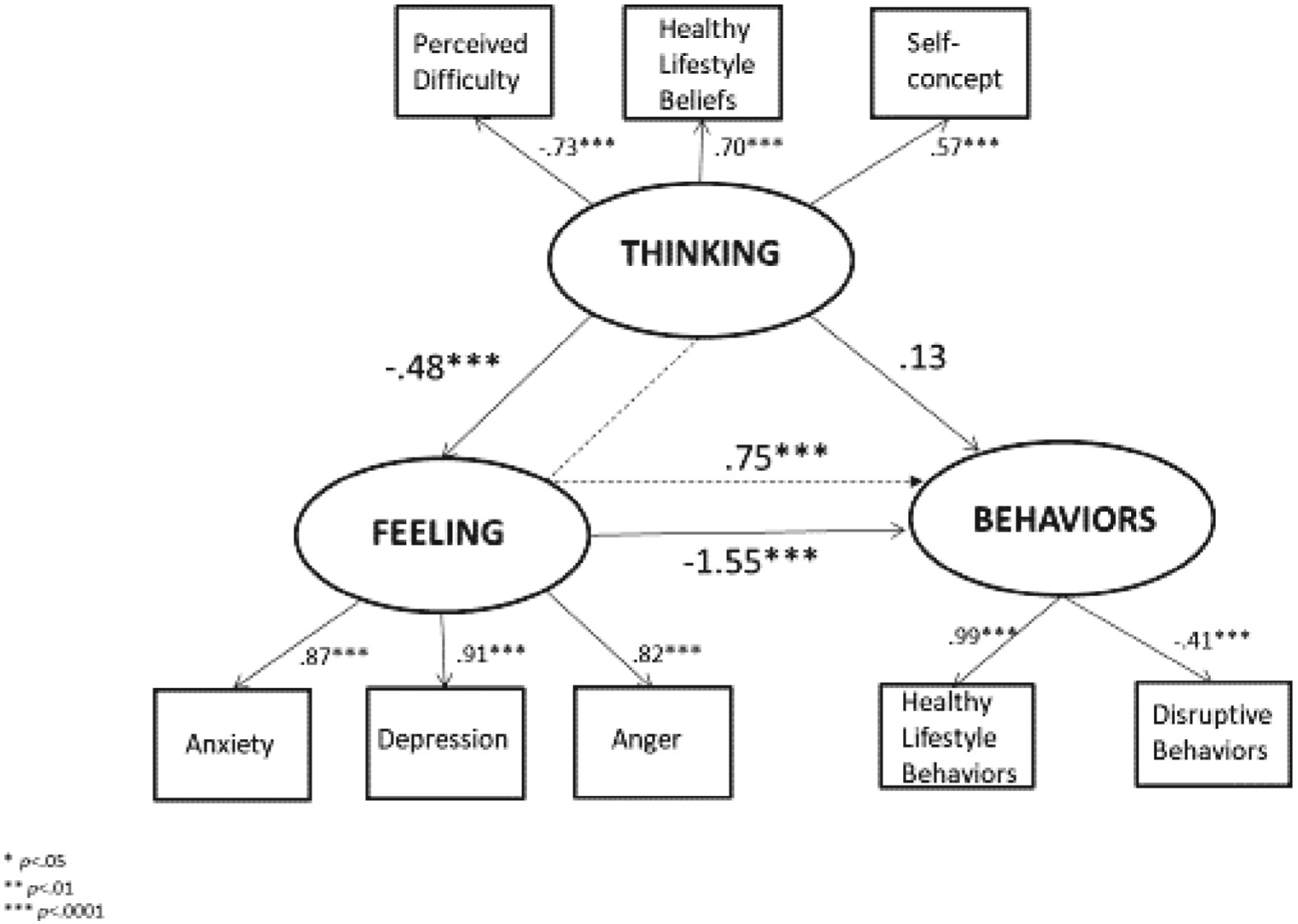

The results showed good fit of the data to the model (Comparative Fit Index = 0.98, Tucker–Lewis index = 0.96, root mean square error of approximation = 0.08, standardized root mean residual = .06): thoughts and feelings influenced behaviors, and differences in the model were observed for males and females, as shown by a substantial decline in model fit (Comparative Fit Index = 0.77, Tucker–Lewis index = 0.67, root mean square error of approximation = 0.22, standardized root mean residual = .15). Figure 2 illustrates the results of the SEM model for males and Figure 3 illustrates the results for females. Among males, positive thoughts were associated with lower levels of negative feelings (i.e., anxiety, anger and depression; B = −0.43, p < .0001), and lower negative feelings were associated with increased healthy lifestyle behaviors and lower disruptive behaviors (B = −1.04, p < .0001). Greater positive thoughts were related to higher reported healthy lifestyle behaviors (B = 0.39, p < .0001). There was a strong indirect effect of thinking through feeling on behaviors (B = 0.45, p < .0001). Similar to males, for females, positive thoughts were associated with lower negative feelings (B = −0.48, p < .0001), and lower negative feelings were associated with increased healthy lifestyle behaviors and lower disruptive behaviors (B = −1.55, p < .0001). However, a direct effect for thoughts on healthy lifestyle behaviors was not observed for females. The indirect pathway from thinking through feeling on behaviors was stronger for females (B = .75, p < .0001) than for males.

FIGURE 2.

Structural equation model for thinking, feeling, and behavior triangle: Males.

*p < .05

**p < .01

***p < .0001

FIGURE 3.

Structural equation model for thinking, feeling, and behavior triangle: Females.

*p < .05

**p < .01

***p < .0001

DISCUSSION

The need to enhance healthy lifestyle behaviors in adolescents to prevent health behavior–related chronic conditions and long-term deleterious health outcomes have become a national imperative. Evidence reviews have indicated that self-efficacy, or the belief that one can affect change, and outcome expectations can act as mediators for increasing healthy lifestyle behaviors in children and adolescents (Cerin, Barnett, & Baranowski, 2009; Lubans, Foster, & Biddle, 2008; Van Stralen et al, 2011). Findings from our study highlight the powerful impact that cognitive beliefs toward engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors, perceived difficulty, and self-concept have on healthy lifestyle behaviors (Cheie & Miu, 2016; Power, Ullrich-French, Steele, Daratha, & Bindler, 2011; Suchert, Hanewinkel, & Isensee, 2015).

Findings from this study support the CBT model: adolescents who have more positive thoughts about engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors reported less negative feelings and engaged in more healthy lifestyle behaviors. These associations strongly support CT, which emphasizes the interconnected relationships between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Beck, 2011). Collectively, our findings highlight the need for healthy lifestyle interventions to target adolescents’ cognitive beliefs. Similar to CBT, targeting maladaptive thinking with cognitive behavioral skills–building interventions may influence healthy behaviors. In the randomized controlled trial from which these secondary data analyses were conducted, adolescents who received a 15-session cognitive behavioral skills–building healthy lifestyle program entitled COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment) Healthy Lifestyles TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, and Nutrition) versus those who received an attention control program had (a) increased levels of physical activity, (b) lower body mass index, (c) fewer depressive symptoms (in those who had severe depression at baseline), and (d) less alcohol use (Melnyk et al., 2015). The 15-session program is composed of seven cognitive behavioral skills–building sessions and eight sessions that focus on healthy eating and physical activity. The COPE program is now recognized as an evidence-based obesity control program for adolescents by the National Cancer Institute’s Research Tested Intervention Programs. The National Cancer Institute is dedicated to “moving science into programs for people” and currently has a repository of over 170 evidence-based intervention programs available for access (https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/index.do; National Cancer Institute, 2016).

The results of the model test also showed sex differences in the thinking–feeling–behaving triangle. Our findings suggest that for adolescent males, there is a direct effect from thoughts to both feelings and behaviors, but not for females. Males (in Table) had stronger beliefs about engaging in healthy lifestyles, fewer negative feelings, and more positive behavior scores compared with females. It is possible that fewer negative feelings allowed for a direct path from beliefs to behaviors. Conversely, for adolescent females, who had higher reported negative feelings, our model indicated a direct effect from thoughts to feelings. These findings further support the model, because females in this sample had lower reported self-concept and healthy lifestyle beliefs (thoughts), higher depression and anger (feelings), and higher disruptive behaviors (behaviors) compared with males. Although recent evidence highlights increased internalizing symptoms in adolescent females (Bor et al., 2014), we also found a significant indirect effect from thoughts through feelings to behaviors for both males and females. This is an important finding. Although intervention strategies for adolescents should target beliefs that undermine health, recognizing and addressing negative emotions is vital to successful behavioral outcomes.

The interplay between physical and mental health can have lifelong effects. Cognitive behavior skills such as cognitive reframing, stress management, and goal setting become critically important as interventions for adolescents, particularly because this population is at higher risk for skill deficits because their executive functions are still developing (Casey & Caudle, 2013; Churchwell & Yurgelun-Todd, 2013).

Based on our results, adolescent males perceived a higher degree of difficulty engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors and thus may do better with an increased emphasis on skills-building activities such as goal setting, problem solving, and overcoming barriers. Females had lower healthy lifestyle beliefs scores compared with their male counterparts, suggesting that an increased emphasis on intervention strategies directed at cognitive reframing and positive self-talk may be necessary.

Our results highlighted the importance of mental health in adolescents’ abilities to engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental health problem in adolescents, and depressive symptoms severe enough to impair daily functioning are reported by 36% of females and 21% of males (Perou et al., 2013). Numerous factors can contribute to higher mortality related to mental health. Results from a study by Cohen et al. (2015) indicated that perception of lack of parental support and self-criticism interacted with anxiety to predict future depressive symptoms, particularly in adolescent females. U.S. guidelines recommend screening adolescents for depression (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2016); however, our results suggest that scope of practice for adolescent screening and interventions may need to be broad-ened to improve joint mental and physical health outcomes. Putting tools in place to more accurately reflect mental and physical health in adolescent populations may increase the likelihood of engagement in health behaviors and the success of different treatment modalities.

Implications for Practice

Findings from this study strongly support effective and efficient resources for use in primary care. With the rise in health behavior-related chronic conditions and mental health disorders in adolescents, primary care screening for both mental and physical health problems is imperative. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening of all 12- to 18-year olds for depression (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2016). However, adolescents are often not screened because practices do not have systems in place to deal with teens who are depressed. To address this issue, the seven cognitive behavioral skills–building sessions in the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN program are being used with positive outcomes in primary care and school settings to provide evidence-based cognitive behavioral skills to depressed and/or anxious adolescents (Hoying et al., 2016; Melnyk et al., 2015).

In our study, almost 44% of participants reported elevated symptoms of anxiety. The proportions of elevated depression (31.8%), anger (16.8%), and disruptive behaviors (21.8%) were also higher than the national averages (Perou et al., 2013). These results support the need for mental health screening, including for disruptive behaviors, for adolescents, using reliable and valid measures. Perou et al. (2013) advocate for the implementation of standardized measures and screening guidelines for clinical practice, but screening is not enough. The establishment and use of evidence-based tools and interventions to support adolescent mental health and healthy lifestyle behaviors is imperative. Based on evidence to date, cognitive behavioral strategies to increase the likelihood of success should be at the core of interventions.

Adolescents who engage in healthy lifestyle behaviors report a higher quality of life and fewer depressive symptoms (Iannotti & Wang, 2013). With limited time and resources, adolescents should be screened for mental health symptoms including depression, anxiety, anger, and disruptive behaviors. Both males and females have benefitted from interventions with cognitive behaviorskills–building interventions in prior studies (Melnyk et al., 2015).Habits formed during the teenage years can have lifelong implications; therefore, it is vital to support the development and sustainability of healthy lifestyle behaviors in this population.

Strengths and Limitations

The data provided further support for the importance of healthy lifestyle beliefs and self-concept on healthy lifestyle behaviors. A strength of this study was the inclusion of mental health, because it relates to the larger picture of healthy lifestyle behaviors outside of diet and physical activity. Another strength was that the inclusion of both mental health and sex variables in the analysis provides preliminary evidence for a priori longitudinal research in the future.

This was a secondary data analysis, and therefore only questions related to the data captured can be answered. Measures relied on self-report, which carries the risk of response bias. Finally, the data for these analyses were cross-sectional; therefore, causal inferences cannot be made. Nonetheless, this study provides a platform for future longitudinal research and the development and improvement of CBT interventions needed to guide evidence-based practice.

CONCLUSION

To increase engagement in healthy lifestyle behaviors, our results suggest screening and targeting adolescents’ cognitive beliefs about engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors. Brief, valid, and reliable measures can be implemented in primary care and in schools to identify adolescents at risk for negative mental and physical health outcomes. Resources to promote healthy lifestyle choices in adolescent populations need to be more comprehensive to encompass cognitive beliefs that target physical and mental health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The original study was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research 1R01NR012171 (Bernadette Melnyk, principal investigator). Manuscript preparation by Colleen M. McGovern was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32NR014225). The content is based solely on the perspectives of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Findings from this study support the CBT model: adolescents who have more positive thoughts about engaging in healthy lifestyle behaviors reported less negative feelings and engaged in more healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Footnotes

Bernadette Melnyk has a company, COPE2THRIVE, that disseminates the COPE program. The other authors report no conflicts of interest.

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01704768.

Some of the data in this manuscript were presented at the Council for the Advancement of Nursing Science conference. No previous manuscripts have been published with the analyses from this study.

Contributor Information

Colleen M. McGovern, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH..

Lisa K. Militello, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH..

Kimberly J. Arcoleo, Center for Research Support, University of Rochester School of Nursing, Rochester, NY..

Bernadette M. Melnyk, University Chief Wellness Officer; Dean and Professor, College of Nursing; and Professor of Pediatrics and Psychiatry, College of Medicine, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH..

REFERENCES

- Altemus M, Sarvaiya N, & Epperson CN (2014). Sex differences in anxiety and depression clinical perspectives. YFRNE Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35, 320–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Swendsen J, He J-P, Burstein M, & Merikangas KR (2015). Major depression in the national comorbidity survey-adolescent supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bor W, Dean AJ, Najman J, & Hayatbakhsh R (2014). Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48, 606–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braet C, & Van Winckel M (2000). Long-term follow-up of a cognitive behavioral treatment program for obese children. BETH Behavior Therapy, 31, 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, & Caudle K (2013). The teenage brain: Self control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22, 82–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerin E, Barnett A, & Baranowski T (2009). Testing theories of dietary behavior change in youth using the mediating variable model with intervention programs. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 41, 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheie L, & Miu AC (2016). Functional and dysfunctional beliefs in relation to adolescent health-related quality of life. Personality and Individual Differences, 97(11), 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Churchwell JC, & Yurgelun-Todd DA (2013). Age-related changes in insula cortical thickness and impulsivity: Significance for emotional development and decision-making. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 6(8), 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JR, Spiro CN, Young JF, Gibb BE, Hankin BL, & Abela JRZ (2015). Interpersonal risk profiles for youth depression: A person-centered, multi-wave, longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43, 1415–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynos AF, & O’Donohue WT (2012). Universal childhood and adolescent obesity prevention programs: Review and critical analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 383–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoying J, Melnyk BM, & Arcoleo K (2016). Effects of the COPE cognitive behavioral skills building TEEN program on the healthy lifestyle behaviors and mental health of Appalachian early adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 30, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannotti RJ, & Wang J (2013). Trends in physical activity, sedentary behavior, diet, and BMI among US adolescents, 2001–2009. Pediatrics, 132, 606–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaisari P, Yannakoulia M, & Panagiotakos DB (2013). Eating frequency and overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 131, 958–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Lock J, Agras WS, Bryson SW, & Jo B (2015). Randomized clinical trial of family-based treatment and cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent bulimia nervosa. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54, 886–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Clarke GN, Hops H, & Andrews J (1990). Cognitive-behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents. BETH Behavior Therapy, 21, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Linardon J, Wade T, de la Piedad Garcia X, & Brennan L (2017). Psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa on symptoms of depression: A meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50, 22763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock J (2015). An update on evidence-based psychosocial treatments for eating disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 707–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubans DR, Foster C, & Biddle SJH (2008). A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 47, 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk B (2014). COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment): A TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, and Nutrition) healthy lifestyles program Columbus, Ohio: COPE2Thrive. Retrieved from http://www.cope2thrive.com/ [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Jacobson D, Kelly SA, Belyea MJ, Shaibi GQ, Small L, … Marsiglia FF (2015). Twelve-month effects of the COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN program on overweight and depressive symptoms in high school adolescents. Journal of School Health, 85, 861–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, Kelly S, Jacobson D, Belyea M, Shaibi G, Small L, … Marsiglia FF (2013). The COPE healthy lifestyles TEEN randomized controlled trial with culturally diverse high school adolescents: Baseline characteristics and methods. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 36, 41–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnyk BM, & Moldenhauer Z (2006). The KySS guide to child and adolescent mental health screening, early intervention and health promotion. Cherry Hill, NJ: National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2017). Mplus User’s Guide (Eighth ed). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute (2016). Research-tested intervention programs: Moving science into programs for people. Retrieved from https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/reference/fact_sheet.pdf

- Perou R, Bitsko R, Blumberg SJ, Pastor P, Ghandour R, Gfroerer R, … Huang LN (2013). Mental health surveillance among children—United States, 2005–2011. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 62(2), 1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TG, Ullrich-French SC, Steele MM, Daratha KB, & Bindler RC (2011). Obesity, cardiovascular fitness, and physically active adolescents’ motivations for activity: A self-determination theory approach. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 12, 593–598. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner B (1960). Science and human behavior. New York: Mc-Millan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Suchert V, Hanewinkel R, & Isensee B (2015). Sedentary behavior and indicators of mental health in school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine Preventive Medicine, 76(Pt. 3), 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate EB, Spruijt-Metz D, Pickering TA, & Pentz MA (2015). Two facets of stress and indirect effects on child diet through emotion-driven eating. Eating Behaviors, 18(8), 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. (2015). Depression (NIH publication no. 15–3561) Bethesda, MD: U.S. Government Printing Office; Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression-what-you-need-to-know/index.shtml [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Final recommendation statement: Depression in children and adolescents: Screening. Retrieved from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/depression-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1

- Van Stralen MM, Yildirim M, te Velde SJ, Brug J, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ, & ENERGY-consortium. (2011). What works in school-based energy balance behaviour interventions and what does not? A systematic review of mediating mechanisms. International Journal of Obesity, 35, 1251–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Kolko RP, & Kass AE (2011). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for weight management and eating disorders in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20, 271–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler A, Dörsing B, Rief W, Shen Y, & Glombiewski JA (2013). Treatment of internet addiction: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 317–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]