Abstract

Background

Hepatic encephalopathy is a devastating complication of cirrhosis.

Aim

To describe the outcomes after developing hepatic encephalopathy among contemporary, aging patients

Methods

We examined data for a 20% random sample of United States Medicare enrollees with cirrhosis and Part D prescription coverage from 2008–2014. Among 49,164 persons with hepatic encephalopathy, we evaluated the associations with transplant-free survival using Cox proportional hazard models with time-varying covariates (hazard ratios, HR) and incidence-rate ratios (IRR) for healthcare utilization measured in hospital-days and 30-day readmissions per person-year. We validated our findings in an external cohort of 2,184 privately insured patients with complete lab values.

Results

Hepatic encephalopathy was associated with median survivals of 0.95 and 2.5 years for those ࣙ65 or <65-years old and 1.1 versus 3.9 years for those with and without ascites. Non-alcoholic fatty-liver disease posed the highest adjusted risk of death among etiologies, HR 1.07 95%CI(1.02,1.12). Both gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin utilization were associated with lower mortality, respective adjusted-HR 0.73 95%CI(0.67, 0.80) and 0.40 95%CI(0.39, 0.42). 30-day readmissions were fewer for patients seen by gastroenterologists [0.71 95%CI(0.57–0.88)] and taking rifaximin [0.18 95%CI(0.08–0.40)]. Lactulose-alone was associated with fewer hospital-days, IRR 0.31 95%CI(0.30–0.32), than rifaximin-alone, 0.49 95%CI(0.45–0.53), but the optimal therapy combination lactulose/rifaximin, IRR 0.28 95%CI(0.27–0.30). These findings were validated in the privately insured cohort adjusting for Model for Endstage Liver Disease-Sodium score and serum albumin.

Conclusions

Hepatic encephalopathy remains morbid and associated with poor outcomes among contemporary patients. Gastroenterology consultation and combination lactulose-rifaximin are both associated with improved outcomes. These data inform the development of care coordination efforts for persons with cirrhosis.

Keywords: Liver Disease, Ascites, Gastroenterology, Rifaximin, NAFLD

Introduction

Cirrhosis is increasingly common. Its prevalence has doubled in the last decade.1 Further, mortality due to cirrhosis rose by 65% from 2008–2016 without sign of slowing.2–7 The complexity and costs of cirrhosis are linked most closely to the complications of cirrhosis. Among these complications, none carry a more abrupt increase in mortality than hepatic encephalopathy.8–13 Hepatic encephalopathy is the most potent risk factor for hospitalization, accidental trauma, and mortality.14–17 The estimated incidence of hepatic encephalopathy is 11.6 per 100-person years,18 rises to 40% by 5 years and is accompanied by a survival <40% by 12 months after the development of hepatic encephalopathy.11, 13 However, the epidemiology of cirrhosis has shifted,7 with an unclear impact on patient outcomes after developing hepatic encephalopathy in a contemporary cohort.

Driven by emerging risk factors, such as Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD),19 patients with cirrhosis are presenting at increasingly older ages.20, 21 Data regarding the outcomes of hepatic encephalopathy have been drawn from younger (<60 years old) cohorts of patients without access to contemporary supportive care.8–13 In recent years there is increasing awareness of the benefits of nutritional support,22, 23 mounting data on the benefits of coordinated care with subspecialists,24 and novel pharmacotherapies for secondary prophylaxis of hepatic encephalopathy episodes.22 Optimized therapy using combination lactulose and rifaximin may not only prevent episodes of hepatic encephalopathy but could reduce overall mortality.25–27

Herein, we evaluate the clinical outcomes after hepatic encephalopathy in two population-based cohort of patients with cirrhosis, focusing on 49,000 Medicare-enrollees and validating our findings in 2,000 privately insured patients.

Methods

Study Population

First, we examined data from a 20% random sample of US Medicare enrollees with cirrhosis (ICD9 571.2, 571.5, 571.6) and continuous Part D (prescription) coverage from 2008–2014.(Supplementary Figure 1) Patients were included from the time of their first cirrhosis diagnosis within the study period and were followed thereafter. A summary of diagnostic codes used is provided in Supplementary Table 1. We included all patients who met criteria for cirrhosis using a coding algorithm validated for Medicare data (≥ 2 diagnostic codes for cirrhosis).28 This study is a continuation of a prior examination of the incidence and risk-factors for hepatic encephalopathy in the Medicare population.18 Subjects were followed until death, transplant, or the end of study (12/31/2014, because ICD-10 replaced ICD-9 in 2015). In order to evaluate the impact of medication usage, we limited our analyses to beneficiaries enrolled in Medicare Part D. We excluded all patients with less than 90-days of outpatient follow up before developing HE. Second, we validated our findings in an external cohort of privately insured patients with cirrhosis with available laboratory data. Complete details of the validation cohort are available in the Supplement. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board.

Definition of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Incident hepatic encephalopathy was defined based on ICD-9 code 572.2 or the prescription of lactulose or rifaximin for >90 days (less if death or transplantation occurred before 90 days), whichever came first. The diagnostic code (572.2) has a specificity of 95–99%.29, 30 As previously published,13, 31 we maximized sensitivity for incident hepatic encephalopathy using pharmacy linkage to include prescription of medications that are specific for hepatic encephalopathy therapy.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was survival after hepatic encephalopathy. As below, we model this outcome in multiple ways including as transplant-free survival and accounting for the competing risks of transplant. Patients were followed until death, transplant, or the end of study. Secondary outcomes included hospital-days per patient-year and 30-day readmissions per patient-year.

Covariates

For complete description of the cohort and risk-adjustment we also included age, sex, race, Charlson Comorbidity Index (modified to exclude liver disease),32 liver disease etiology, complications of cirrhosis, and evaluation by a gastroenterologist/hepatologist. Patients could have multiple causes of cirrhosis (e.g. hepatitis B and C, hepatitis C and alcohol related liver disease). As performed by multiple investigators, we classified a group of patients with likely NAFLD-related cirrhosis who had cirrhosis (ICD-9 571.5) but lacked any diagnostic codes for viral hepatitis, alcohol-related use disorder or alcohol-related organ injury, or auto-immune liver disease.33, 34 For lack of specific codes for NAFLD, we refer to this as non-alcohol, non-viral related cirrhosis. Liver disease severity was assessed using a combination of codes for diagnosis (e.g. ascites, variceal bleeding), and procedures (e.g. paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement). We categorized hepatitis C therapy using Part D dispensing records (Supplementary Table 1). For the external cohort where we had access to laboratory data, we also adjusted for MELD-Na (model for endstage liver disease-sodium), serum albumin, and platelet count at the time of hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis.

We analyzed two potentially modifiable factors. First, given that it has been associated with decreased hospitalization risk in randomized and observational studies,22, 35 we explored impact of rifaximin use on our outcomes adjusted for the covariates described above. Second, we evaluated the association of our primary and secondary outcomes with gastroenterology consultation.

Data Analyses

We used 4 analytic strategies to evaluate our outcomes accounting for biases.

First, to account for varying trajectories of disease we employed multivariate Cox proportional hazard models for transplant-free survival using time-varying covariates with first-order autoregressive modeling. This method accounts for the temporal relationship of covariates (i.e. decompensation events during follow-up, progressive development of comorbidities, duration of exposure, and the temporal proximity of the exposure to the outcome). We performed a sensitivity analysis of these data for persons diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy as inpatients in an attempt to isolate those whose first diagnosis was with overt hepatic encephalopathy.

Second, to account for diagnoses that developed but were not coded or treated prior to the transition from private to Medicare insurance, we repeated our analyses for all persons with a minimum of 1 year of follow-up without hepatic encephalopathy (i.e. washout).

Third, we addressed the risk of residual immortal time bias despite the use of time-dependent Cox modelling using a Landmark analysis,36 setting the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy as time-zero.

Fourth, we employed Fine-Gray modeling to account for the competing risk of liver transplantation.37

Fifth, we analyzed an external/validation cohort where we could fully adjust our risk-estimates using laboratory data (MELD-Na, albumin, platelet count). We included only patients with 1-year of follow-up without hepatic encephalopathy (washout) and performed all outcome assessments using a competing-risk (death vs. transplant) landmark analysis (setting the diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy as time-zero). We adjusted all analyses using variables that were present at the time of hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis (or within 30-days).

Hospital-days and readmissions were evaluated in negative binomial models and presented as the incidence per person-years and incidence rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI). As the number of 30-day readmissions was left-skewed (clustered around zero), we used a zero-inflated negative binomial model. The difference in separation of survival curves was evaluated using the Log-Rank test. In all cases, the p-values presented were 2-tailed with a <0.05 threshold for significance. All analyses were performed using R and SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Medicare Cohort

Of the 49,164 (26.4%) patients diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy, 50% had alcohol-related cirrhosis and 38% had HCV (including some with alcohol-related cirrhosis). At the time of hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis, 43% had ascites (13% required paracentesis), 21% had varices, and 7% had hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Overall, 49% had received gastroenterology consultation prior to hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis (rising to 67% by the end of follow-up). Overall, 1620 persons had transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts, 704 of whom received it prior to diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Once hepatic encephalopathy was diagnosed, 28,445 (57.8%) received lactulose and 9,615 (19.6%) received rifaximin for at least 90-days (31.2% received <90d-days of either therapy). Of those who received prescriptions, the number of fills per person-year was 3.95±6.89 and 3.83±6.75 for lactulose and rifaximin respectively.

Mortality After the Diagnosis of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Overall, 1-year survival was 48.3% (median survival 0.92 years), including 58% (median 1.4 years) for persons with hepatic encephalopathy defined by medications alone and 44.0% (median 0.76 years) for those with 572.2 ICD-9 codes. Multiple clinical factors were associated with survival after HE. Age was a major determinant.(Supplementary Figure 3) For persons with cirrhosis aged ≥65 years, the median survival overall was 0.95 years compared to 2.5 years for those <65 years old at the time of hepatic encephalopathy (p<0.001). The sequence of decompensation was also important. The median survival was 1.1 years for those with ascites at the time of incident hepatic encephalopathy compared to 3.9 years for those without ascites (p<0.001). For the 704 patients who developed hepatic encephalopathy after tranjugular portosystemic shunt placement, median survival was 0.88 years; it was 1.57 years for the 916 patients with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic after hepatic encephalopathy (including a median of 0.41 years between hepatic encephalopathy development and shunt placement). Only 2.0% of patients underwent liver transplantation.

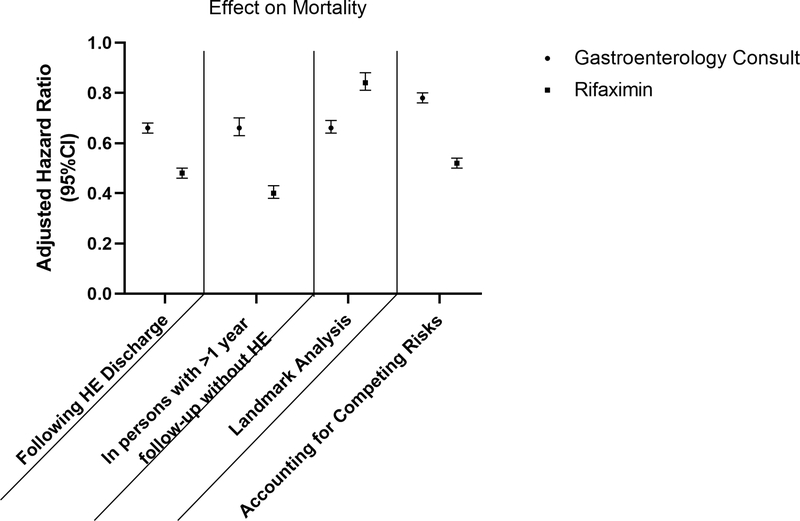

In Table 2, we present a multivariable cox model for survival. The risk of death after hepatic encephalopathy increased with age, male sex, non-alcohol, non-viral-related cirrhosis, comorbidities including endstage renal disease, and other cirrhosis complications. Gastroenterology/hepatology consultation and rifaximin utilization were associated with a lower risk of death, with respective adjusted hazard ratios of 0.73 95%CI(0.67, 0.80) and 0.40 95%CI(0.39, 0.42). Figure 1 details how gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin use are inversely associated with mortality across multiple analytic strategies: when hepatic encephalopathy is first diagnosed as an inpatient, when the cohort is restricted to persons with 1 year of follow-up prior to hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis, and in both the landmark and competing-risk analysis (which are further described with the effect estimates for all covariates in Supplementary Tables 2–4).

Table 2:

Adjusted Outcomes after a Diagnosis of Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Cohort of Medicare Enrollees

| Death | Hospital days | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variable | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted IRR (95%CI) | P-Value |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (1.02, 1.03) | <0.001 | 1.01 (1.01, 1.01) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.21 (1.19, 1.24) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.99, 1.06) | 0.116 |

| Endstage Renal Disease | 1.08 (1.01, 1.14) | 0.015 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 0.707 | 1.04 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.063 |

| Race (relative to White) | ||||

| Black | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | 0.960 | 1.17 (1.10, 1.23) | <0.001 |

| Other | 0.90 (0.87, 0.94) | <0.001 | 0.97 (0.92, 1.03) | 0.353 |

| Cirrhosis Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 0.82 (0.79, 0.85) | <0.001 | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | 0.692 |

| Hepatitis C | 0.87 (0.85, 0.90) | <0.001 | 1.20 (1.15, 1.25) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis B | 1.19 (0.88, 1.61) | 0.980 | 0.79 (0.75, 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Non-alcohol, Non-viral cirrhosis | 1.07 (1.02, 1.12) | 0.004 | 0.98 (0.93, 1.03) | 0.427 |

| Time Varying Covariates | ||||

| Gastroenterology Consult | 0.73 (0.67, 0.80) | <0.001 | 1.07 (1.00, 1.14) | 0.056 |

| Rifaximin | 0.40 (0.39, 0.42) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.33, 0.37) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 4.20 (4.08, 4.32) | <0.001 | 1.86 (1.79, 1.93) | <0.001 |

| Varices | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 0.029 | 0.77 (0.74, 0.80) | <0.001 |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | 1.15 (1.08, 1.23) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.05, 1.24) | 0.002 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 2.27 (2,19, 2.34) | <0.001 | 0.95 (0.91, 1.00) | 0.057 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; relative to CCI 0) | ||||

| CCI=1 | 1.20 (1.17, 1.24) | <0.001 | 1.17 (1.13, 1.22) | <0.001 |

| CCI=2 | 1.26 (1.22, 1.30) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.23, 1.34) | <0.001 |

| CCI=≥3 | 1.42 (1.35, 1.48) | <0.001 | 1.33 (1.24, 1.42) | <0.001 |

All estimates are adjusted for the variables presented in the table. HR = hazard ratio, IRR = incidence rate ratio. Non-alcoholic, non-viral = patients with cirrhosis codes but without any codes for alcohol-related diseases or viral hepatitis or autoimmune hepatitis.

Figure 1. The Effect of Gastroenterology Consultation and Rifaximin Utilization On Mortality.

The effect on mortality of gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin use are modeled for the subset of patients who were first diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy as inpatients, in persons with 1 year of ‘washout’ after enrolling in hepatic encephalopathy without recorded hepatic encephalopathy, as well as after a landmark analysis to extinguish the risk of immortal-time bias and an analysis accounting for the competing-risk of liver transplantation (the effect estimate in this case is a sub-hazard distribution ratio). HE = hepatic encephalopathy

To further explore the effect of gastroenterology/hepatology consultation, we examined the impact of HCV therapy on hepatic encephalopathy outcomes. Overall, 2200 (12%) of the patients with HCV underwent therapy, 1041 of whom received direct-acting antivirals. Among patients with HCV, median survival was 1.13 years, 2.10 years, and 2.12 years for patients receiving no therapy, direct acting antiviral, and interferon-based therapy.

Hospital Utilization After the Diagnosis of Hepatic Encephalopathy

Patients with hepatic encephalopathy were hospitalized for a median of 11.8 days (IQR2.9–38.0) per person-year. Table 2 provides the adjusted risk of hospitalization by clinical covariate for patients after a diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy. Notably, comorbid ascites was associated with the greatest burden of hospital utilization, incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.86 95%CI(1.79–1.93). Overall, older age, number of comorbidities (including endstage renal disease), hepatitis C, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt were all associated with more hospital-days per person-year. Gastroenterology/hepatology consultation was not associated with a reduction adjusted risk for hospital utilization but rifaximin use was, IRR 0.35 95%CI(0.33, 0.37).

In Figure 2, we show how rifaximin and gastroenterology consultation were associated hospital utilization during multiple sensitivity analyses. First, we restricted the cohort to those whose hepatic encephalopathy was first diagnosed as inpatients; gastroenterology consultation with a modest increase in overall hospital-days while rifaximin co-therapy is still associated with fewer hospital-days when hepatic encephalopathy is first diagnosed as an inpatient, IRR 0.80 95%CI(0.76–0.84). Second, similar results were observed when the cohort was restricted to those with ≥1-year follow-up prior to hepatic encephalopathy diagnosis. Third, we also evaluated the frequency of 30-day readmissions per person-year. Both gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin use were associated with lower all-cause 30-day readmissions, respective IRR 0.71 95%CI(0.57–0.88) and 0.18 95%CI(0.08–0.40). Finally, we examined the impact of various combinations of hepatic encephalopathy therapy on hospital-days. We set as the reference the many patients did not receive more than 90-days of hepatic encephalopathy-therapy. Relative to ‘no therapy’, persons receiving lactulose-alone had a markedly lower IRR for hospital-days per person-year than those receiving rifaximin-alone, respective IRR 0.31 95%CI(0.30–0.32) and 0.49 95%CI(0.45–0.53). The relative IRR associated with combination lactulose and rfiaximin was IRR 0.28 95%CI(0.27–0.30).

Figure 2: The Effect of Gastroenterology Consultation and Rifaximin Utilization On Healthcare Utilization After Hepatic Encephalopathy.

The effect on hospitalization associated with both gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin use. Gastroenterology consultation is associated with fewer 30-day readmissions but a higher number of hospital-days in the cohort after an hepatic encephalopathy-discharge as well the cohort with 1 year of ‘washout’. Rifaximin, by contrast is associated with fewer hospitalizations in each analysis. HE = hepatic encephalopathy

External cohort of privately insured patients with Hepatic Encephalopathy

In a cohort of 2,184 patients with hepatic encephalopathy and an average age of 61, MELD-Na of 12, and albumin of 3.1, we found similar demographics, clinical factors and associations with mortality and hospital-utilization.(Table 3) The cumulative incidence of death (accounting for competing risks) at 1,2, and 3 years was 0.19 (0.18–0.21), 0.29 (0.27–0.32), and 0.44 (0.40–0.48). As shown in Supplementary Table 5, the risk of death was highest for patients >65 years old and those with pre-existing ascites. Gastroenterology consultation was much more common (85% prior to hepatic encephalopathy and 90% during follow up) and was not statistically associated with mortality or utilization, irrespective of whether it occurred during the index hospitalization for hepatic encephalopathy. However, rifaximin use was associated with reduced mortality sHR 0.40 (0.39–0.42) and hospital-days IRR 0.35 (0.33–0.37).

Table 3:

Adjust Outcomes after Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Cohort of 2,184 Privately Insured Persons with Cirrhosis

| Death | Hospital days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Variable | Baseline Value | Adjusted sHR (95% CI) | P-Value | Adjusted IRR (95%CI) | P-Value |

| Age (per year) | 61 ± 14 | 1.03 (1.02–1.04) | <0.001 | 1 (0.99–1.01) | 0.963 |

| Male | 1334 (57%) | 1.13 (0.94–1.36) | 0.183 | 0.96 (0.84–1.11) | 0.608 |

| White Race (vs others) | 1460 (62%) | 0.97 (0.81–1.15) | 0.183 | 1.07 (0.93–1.23) | 0.364 |

| Cirrhosis Etiology | |||||

| Alcohol | 1208 (51%) | 0.85 (0.71–1.01) | 0.069 | 0.9 (0.78–1.04) | 0.139 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1264 (54%) | 0.88 (0.74–1.06) | 0.189 | 1.15 (0.99–1.35) | 0.068 |

| Hepatitis B | 199 (8%) | 0.75 (0.54–1.04) | 0.086 | 0.91 (0.71–1.16) | 0.434 |

| Hepatitis C | 1004 (43%) | 0.86 (0.71–1.04) | 0.114 | 0.91 (0.79–1.06) | 0.231 |

| Morbid obesity | 344 (15%) | 0.86 (0.66–1.12) | 0.266 | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) | 0.076 |

| Gastroenterology Consult | 1998 (85%) | 1.23 (0.94–1.61) | 0.127 | 1.11 (0.92–1.34) | 0.266 |

| Lactulose | 863 (37%) | 0.43 (0.36–0.52) | <0.001 | 0.44 (0.38–0.5) | <0.001 |

| Rifaximin | 492 (21%) | 0.58 (0.46–0.72) | <0.001 | 0.56 (0.47–0.66) | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 887 (38%) | 1.15 (0.95–1.39) | 0.165 | 1.13 (0.98–1.3) | 0.091 |

| Variceal bleeding | 169 (7%) | 0.96 (0.67–1.37) | 0.812 | 0.8 (0.61–1.04) | 0.096 |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt | 59 (3%) | 1.03 (0.65–1.61) | 0.913 | 1.41 (0.92–2.17) | 0.115 |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | 255 (11%) | 1.7 (1.31–2.20) | <0.001 | 1.49 (1.2–1.86) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI; relative to CCI 1) | |||||

| CCI=2 | 356 (15%) | 1.46 (0.91–2.35) | 0.117 | 0.77 (0.56–1.08) | 0.128 |

| CCI=≥3 | 1864 (79%) | 1.1 (0.8–1.50) | 0.06 | 0.94 (0.66–1.34) | 0.736 |

| MELD-Na | 14 ± 12 | 1.05 (1.04–1.07) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | <0.001 |

| Albumin g/dL | 3.3 ± 3.3 | 0.71 (0.61–0.83) | <0.001 | 0.83 (0.74–0.93) | 0.001 |

| Platelet count | 147 ± 122 | 1 (1.00–1.002) | 0.011 | 1.002 (1.001–1.003) | <0.001 |

MELD-Na (Model for Endstage Liver Disease – Sodium), TIPS =. sHR = subhazard distribution ratio (accounts for the competing risk of death)

Discussion

Hepatic encephalopathy is a watershed moment in the patient’s experience of chronic liver disease, after which the risk of hospitalization and death sharply rises.16, 38, 39 To evaluate the natural history and outcomes following the development of hepatic encephalopathy, we examined a large sample (>49,000 Medicare-enrollees with hepatic encephalopathy) with long-term follow-up and detailed patient-level characteristics for time-varying risk-adjustment. We also validated our findings in a second cohort of >2,000 privately-insured patients. These data extend our understanding of the natural history of hepatic encephalopathy in multiple ways.

Survival After Hepatic Encephalopathy for Contemporary Patients

Survival is diminished following the development of hepatic encephalopathy with a median survival of 0.92 years. Further, we found that while comorbidities and disease severity impact survival as expected. Non-alcohol, non-viral (mostly NAFLD) cirrhosis also increases the risk of death, adjusted HR 1.07 95%CI(1.02, 1.12). In the privately insured cohort where biochemical measures were available, only MELD-Na, albumin and HCC were associated with mortality. This study builds on prior estimates of survival after decompensation with hepatic encephalopathy, overt or covert, all drawn from the referral setting. For example, Bustamante et al reported 43% survival at 1-year in a cohort of younger persons (none with NAFLD), while Ampuero and Bajaj both demonstrated a higher risk of death or transplantation in persons with covert hepatic encephalopathy.15, 40, 41 In contrast, our study examines two population-based cohorts hundreds-fold larger with both variable exposure to subspecialist consultation and differences in the supportive care provided.

Interventions associated with survival after Hepatic Encephalopathy

Following the development of hepatic encephalopathy, few interventions beyond liver transplantation are associated with improved survival. For reasons thought to be related to improved quality of care, prior studies have found an association with improved survival after gastroenterology consultation for all-comers with chronic liver disease seen in the Veterans Affairs.42, 43 However, fewer than 10% of the patients in these studies had cirrhosis. Further, the impact of subspecialist involvement on patients with hepatic encephalopathy was not evaluated.42, 43 We extend the association of gastroenterology in hepatic encephalopathy volvement with improved survival to a cohort of patients with hepatic encephalopathy with an adjusted hazard ratio of 0.73, 95%CI(0.67–0.80). This association may be mediated by adherence to quality metrics (such as cancer or varices screening),24 HCV therapy,44 referral for transplantation, and use of guideline-concordant therapies for hepatic encephalopathy.

We also show that rifaximin use is associated with improved survival. Rifaxmin reduces the risk of hospitalization for persons with hepatic encephalopathy.22, 35 Hospitalization itself is independently associated with mortality.45 Hospitalization is associated with progressive debility and nosocomial complications making plausible the association between improved outcomes and interventions that safely avoid re-hospitalization. Our study identifies a possible mortality benefit for rifaximin, adjusting for disease severity and gastroenterology consultation. This effect is also observed in our validation cohort where we could adjust for disease severity using laboratory data (ie. MELD-Na). This effect is also robust to multiple analytic strategies to address biases due to competing-risks (with transplant) and immortal-time. Prior studies have suggested that rifaximin carries a mortality benefit.25–27 Most recently Salehi et al showed that rifaximin was associated with decreased bleeding and infections in addition to reduced episodes in cohort of 101 transplant-waitlisted persons with hepatic encephalopathy.26 Our data extends these findings in a cohort hundreds-fold larger with variable exposure to subspecialty consultation while reinforcing that rifaximin monotherapy is inadequate.

Hospital-Days after Hepatic Encephalopathy

Hepatic encephalopathy is the most potent risk factor for repeated hospitalization for patients with cirrhosis.17 These data extend current knowledge both by highlighting the subgroups at highest risk and tools needed to curb hospitalization risk. We show that older persons with alcohol-related liver disease, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts, and multiple comorbidities are at higher risk of hospitalization.

Receipt of appropriate hepatic encephalopathy therapy is crucial. Unfortunately, these data highlight gaps in medical therapy for persons with hepatic encephalopathy. As recently shown by Bajaj, many persons with hepatic encephalopathy are often not even prescribed lactulose after hospitalization for hepatic encephalopathy.46 We too find that many do not receive lactulose. Lactulose therapy is associated with reduced hospital-days – IRR 0.31 95%CI(0.30–0.32). Accordingly, efforts to optimize care begin with lactulose prescription. Conversely, rifaximin monotherapy is common. It appears to be substantially less effective than lactulose monotherapy at preventing hospitalization. Conversely, adjusting for lactulose use, those who receive rifaximin co-therapy are at lower risk of hospitalization – IRR 0.35 95%CI(0.33, 0.37). We also found that both gastroenterology consultation and rifaximin use were associated with lower all-cause 30-day readmissions per person-year, respective IRR 0.71 95%CI(0.57–0.88) and 0.18 95%CI(0.08–0.40). These data confirm the effects of rifaximin co-therapy on healthcare utilization observed in prior randomized and prospective trials and extend these associations to the level of population-based data.22, 35

Optimal Care for Persons with Hepatic Encephalopathy

In sum, our findings consolidate findings from prior studies that speak to the nature of optimal care for patients at high risk of death and repeated hospitalization. In a landmark trial, Morando et al showed that the risk of both death and readmission can be improved with a care co-ordination program.47 Their multipronged intervention involved readily available gastroenterology consultation, testing for and treatment of cognitive dysfunction (i.e. with optimization of lactulose and/or addition of rifaximin), testing for and treatment of alcohol-use disorder, and on-demand procedures such as paracentesis.47 In contrast to this ideal, echoing the findings of prior studies,42, 48 we find that only half (49%) of persons with cirrhosis are evaluated by a gastroenterologist prior to the development of hepatic encephalopathy. Access and referral to gastroenterologists is therefore a key target in the improvement of clinical outcomes and overall healthcare utilization for persons with cirrhosis. Patients who see gastroenterologists are more likely to receive optimal therapy with lactulose and rifaximin,24 receive HCV therapy,44 and timely referral for transplant evaluation. Finally, these data confirm the necessity of continuing lactulose after discharge for hepatic encephalopathy and suggest a role for rifaximin co-therapy for hepatic encephalopathy as part of best practice, particularly for those hospitalized with hepatic encephalopathy or at high-risk for re-hospitalization.

Contextual Factors

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of the study design. First, laboratory results were not available to calculate Model for Endstage Liver Disease scores in the Medicare cohort. However, with laboratory data in the privately insured cohort, there was limited difference in the direction of effect. Second, we could not determine which patients with alcohol-related disease were actively drinking. Third, we have neither access to the staging of hepatic encephalopathy at diagnosis nor the results of any cognitive testing (if it was performed) and therefore it was possible that many patients had earlier stages of hepatic encephalopathy (i.e. covert hepatic encephalopathy). However, we noticed no difference outcomes for persons on the basis of inpatient versus outpatient diagnosis, suggesting that hepatic encephalopathy was a negative prognostic development irrespective of stage. Fourth, although we have prescription fill-rates, we cannot speak to medication adherence. However, it is notable that even suboptimal fill-rates, combination lactulose and rifaximin use was associated with improved outcomes. Fifth, although gastroenterology consultation would be expected to reflect sicker patients (confounding by indication), it was associated with lower risk of death and hospitalization lending credence to a true effect. Subspecialty consultation access is complex and likely related to multiple unmeasured factors. Given the proportion with access in the private insurance cohort (90%), we could not meaningfully validate this finding outside Medicare.

Conclusion

Hepatic encephalopathy is common and morbid. These data provide the data necessary to inform contemporary patients of their prognosis and suggest a role for interventions that are linked to improved survival and reduced hospitalization. Efforts to expand and co-ordinate access to expert consultation, reinforce lactulose use after discharge, and reduce the cost-barrier of rifaximin may be warranted to improve outcomes for the population with cirrhosis.

Supplementary Material

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Study Cohort

| Clinical Characteristics at the time of Hepatic Encephalopathy Diagnosis | Patients with Hepatic Encephalopathy (N=49,164) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 63 (55, 71) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 27,515 (56) |

| White Race, n (%) | 38,076 (78) |

| Medicaid co-insurance, n (%) | 15,293(31) |

| Urban, n (%) | 39,827 (81) |

| Charlson Index | |

| 0 | 17,259 (35) |

| 1 | 17,714 (36) |

| 2 | 10,462 (21) |

| ≥3 | 3,324 (7) |

| Endstage Renal Disease, n (%) | 1,828 (4) |

| Disabled, n (%) | 22,259 (46) |

| Cirrhosis etiology, n (%) | |

| Alcohol | 24,183 (50) |

| Hepatitis C | 18,352 (38) |

| Non-alcohol, non-viral | 15,048 (31) |

| Hepatitis B | 2,589 (5) |

| Ascites, n(%) | 20,771 (43) |

| Paracentesis, n(%) | 6,474 (13) |

| Varices, n(%) | 10,297 (21) |

| Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, n(%) | 704 (1) |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma, n(%) | 3,361 (7) |

| Gastroenterology consult, n(%) | 24,090 (49) |

HE= Hepatic encephalopathy, Note: many patients had both alcohol-related and hepatitis C cirrhosis.

Acknowledgments

4. Funding: Elliot Tapper receives funding from the National Institutes of Health through the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research (KL2TR002241) and NIDDK (1K23DK117055–01A1). This work was supported in part by an unrestricted research grant from Valeant Pharmaceuticals (makers of Rifaximin). Valeant had no access to the data at any point and played no role in the planning of the study or the analysis or interpretation of the data.

Footnotes

3. Conflicts of interest: Elliot Tapper has served as a consultant to Norvartis and Allergan, has served on advisory boards for Mallinckrodt and Bausch Health, and has received unrestricted research grants from Gilead and Valeant. Valeant is the maker of Rifaximin, a medication approved for treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Neehar Parikh has served as a consultant to Bristol Myers-Squibb, Exelexis, Freenome, Eli Lilly, Fujifilm, and Exact Sciences, has served on advisory boards for Merck, Exelexis, Bayer, Eisai, and has received research funding from Bayer, Exact Sciences and Target Pharmasolutions, No other author has a conflict of interest.

Disclosure

1. Elliot Tapper is the guarantor of this article

2. Roles

a. Concept: Tapper,

b. Analysis: Tapper, Aberasturi, Zhao, Hsu, Parikh

c. Data acquisition: Tapper, Aberasturi, Zhao, Hsu

d. Writing: Tapper

e. Revision: Aberasturi, Parikh, Zhao, Hsu

References

- 1.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, et al. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001–2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1471–1482. e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, et al. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moon A, Green P, Berry K, et al. Transformation of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a national healthcare system following the introduction of direct antiviral agents. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017;45:1201–1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh ND, Marrero WJ, Wang J, et al. Projected increase in obesity and non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis‐related liver transplantation waitlist additions in the United States. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2011;9:524–530. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tapper EB, Parikh ND. Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999–2016: observational study. BMJ 2018;362:k2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moon AM, Singal AG, Tapper EB. Contemporary Epidemiology of Chronic Liver Disease and Cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gomez EV, Rodriguez YS, Bertot LC, et al. The natural history of compensated HCV-related cirrhosis: a prospective long-term study. Journal of hepatology 2013;58:434–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dienstag JL, Ghany MG, Morgan TR, et al. A prospective study of the rate of progression in compensated, histologically advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2011;54:396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konerman MA, Zhang Y, Zhu J, et al. Improvement of predictive models of risk of disease progression in chronic hepatitis C by incorporating longitudinal data. Hepatology 2015;61:1832–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gines P, Quintero E, Arroyo V, et al. Compensated cirrhosis: natural history and prognostic factors. Hepatology 1987;7:122–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jepsen P, Ott P, Andersen PK, et al. Clinical course of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: A Danish population‐based cohort study. Hepatology 2010;51:1675–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tapper EB, Parikh N, Sengupta N, et al. A Risk Score to Predict the Development of Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Population‐Based Cohort of Patients with Cirrhosis. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Tandon P, et al. Hepatic Encephalopathy Is Associated With Mortality in Patients With Cirrhosis Independent of Other Extrahepatic Organ Failures. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2017;15:565–574.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patidar KR, Thacker LR, Wade JB, et al. Covert Hepatic Encephalopathy Is Independently Associated With Poor Survival and Increased Risk of Hospitalization. The American Journal Of Gastroenterology 2014;109:1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ezaz G, Murphy SL, Mellinger J, et al. Increased Morbidity and Mortality Associated with Falls among Patients with Cirrhosis. The American journal of medicine 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tapper EB, Halbert B, Mellinger J. Rates of and Reasons for Hospital Readmissions in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Multistate Population-based Cohort Study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tapper EB, Henderson JB, Parikh ND, et al. Incidence of and Risk Factors for Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Population‐Based Cohort of Americans With Cirrhosis. Hepatology Communications 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parikh ND, Marrero WJ, Wang J, et al. Projected increase in obesity and non‐alcoholic‐steatohepatitis–related liver transplantation waitlist additions in the United States. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scaglione S, Kliethermes S, Cao G, et al. The epidemiology of cirrhosis in the United States. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 2015;49:690–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharpton SR, Feng S, Hameed B, et al. Combined effects of recipient age and model for end-stage liver disease score on liver transplantation outcomes. Transplantation 2014;98:557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. New England Journal of Medicine 2010;362:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bajaj JS, Acharya C, Fagan A, et al. Proton Pump Inhibitor Initiation and Withdrawal affects Gut Microbiota and Readmission Risk in Cirrhosis. The American journal of gastroenterology 2018:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tapper EB, Hao S, Lin M, et al. The Quality and Outcomes of Care Provided to Patients with Cirrhosis by Advanced Practice Providers. Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharma BC, Sharma P, Lunia MK, et al. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial comparing rifaximin plus lactulose with lactulose alone in treatment of overt hepatic encephalopathy. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2013;108:1458–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehi S, Tranah TH, Lim S, et al. Rifaximin reduces the incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, variceal bleeding and all‐cause admissions in patients on the liver transplant waiting list. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2019;50:435–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimer N, Krag A, Møller S, et al. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: the effects of rifaximin in hepatic encephalopathy. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2014;40:123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakoski MO, McCammon RJ, Piette JD, et al. Burden of cirrhosis on older Americans and their families: analysis of the health and retirement study. Hepatology 2012;55:184–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nehra MS, Ma Y, Clark C, et al. Use of administrative claims data for identifying patients with cirrhosis. Journal of clinical gastroenterology 2013;47:e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Re VL III, Lim JK, Goetz MB, et al. Validity of diagnostic codes and liver‐related laboratory abnormalities to identify hepatic decompensation events in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety 2011;20:689–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tapper EB, Korovaichuk S, Baki J, et al. Identifying patients with hepatic encephalopathy using administrative data in the ICD-10 era. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. Journal of clinical epidemiology 1992;45:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mellinger JL, Shedden K, Winder GS, et al. The High Burden of Alcoholic Cirrhosis in Privately Insured Persons in the United States. Hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allen AM, Therneau TM, Larson JJ, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease incidence and impact on metabolic burden and death: A 20 year‐community study. Hepatology 2018;67:1726–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tapper EB, Finkelstein D, Mittleman MA, et al. A Quality Improvement Initiative Reduces 30-Day Rate of Readmission for Patients With Cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson JR. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol 1983;1:710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. Journal of the American statistical association 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tapper EB, Risech-Neyman Y, Sengupta N. Psychoactive medications increase the risk of falls and fall-related injuries in hospitalized patients with cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2015;13:1670–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajaj JS, Saeian K, Schubert CM, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy is associated with motor vehicle crashes: the reality beyond the driving test. Hepatology 2009;50:1175–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ampuero J, Simón M, Montoliú C, et al. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy and critical flicker frequency are associated with survival of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bustamante J, Rimola A, Ventura P-J, et al. Prognostic significance of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Journal of hepatology 1999;30:890–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mellinger JL, Moser S, Welsh DE, et al. Access to subspecialty care and survival among patients with liver disease. The American journal of gastroenterology 2016;111:838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Su GL, Glass L, Tapper EB, et al. Virtual Consultations Through the V eterans A dministration SCAN‐ECHO Project Improves Survival for Veterans With Liver Disease. Hepatology 2018;68:2317–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tapper EB, Parikh ND, Green PK, et al. Reduced Incidence of Hepatic Encephalopathy and Higher Odds of Resolution Associated With Eradication of HCV Infection. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, et al. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. The American journal of gastroenterology 2012;107:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bajaj JS, O’Leary JG, Tandon P, et al. Targets to improve quality of care for patients with hepatic encephalopathy: data from a multi‐centre cohort. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morando F, Maresio G, Piano S, et al. How to improve care in outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites: a new model of care coordination by consultant hepatologists. Journal of hepatology 2013;59:257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mellinger JL, Volk ML. Multidisciplinary management of patients with cirrhosis: a need for care coordination. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2013;11:217–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.