Abstract

Background:

Although scientific reports increasingly document the negative impact of inadequate health literacy on health-seeking behaviors, health literacy’s effect on health outcomes in patients with diabetes is not entirely clear, owing to insufficient empirical studies, mixed findings, and insufficient longitudinal research.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to empirically examine underlying mechanisms of health literacy’s role in diabetes management among a group of Korean Americans with Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods:

Data from a randomized clinical trial of a health literacy-focused Type 2 diabetes self-management intervention conducted during 2012–2016 in the Korean American community were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months. A total of 250 Korean Americans with Type 2 diabetes participated (intervention, 120; control, 130). Participants were first-generation Korean American immigrants. Health literacy knowledge was measured with the original Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine and the diabetes mellitus-specific Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine. Functional health literacy was measured with the numeracy subscale of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults and the Newest Vital Sign screening instrument, which also uses numeracy. Primary outcomes included glucose control and diabetes quality of life. Multivariate analyses included latent variable modeling.

Results:

A series of path analyses identified self-efficacy and self-care skills as significant mediators between health literacy and glucose control and quality of life. Education and acculturation were the most significant correlates of health literacy.

Discussion:

Despite inconsistent findings in the literature, this study indicates that health literacy may indirectly influence health outcomes through mediators such as self-care skills and self-efficacy. The study highlights the importance of health literacy, as well as underlying mechanisms with which health literacy influences processes and outcomes of diabetes self-management.

Keywords: community-based self-help intervention, glucose control, health literacy, Type 2 diabetes, quality of life, self-care, self-efficacy

Healthy literacy’s (HL) significant role in the healthcare system is well documented. People with limited or low HL are likely, for example, to be at higher risk for use of inappropriate emergency care services (Griffey, Kennedy, McGownan, Goodman, & Kaphingst, 2014), hospitalization (Wu et al., 2013), and higher medical costs (Howard, Gazmararian, & Parker, 2005), and they are less likely to use preventive health services (Chen, Hsu, Tung, & Pan, 2013). The negative effect of inadequate HL on various health outcomes, including successful management of chronic disease, is also well documented; effects include mismanaging high blood pressure (McNaughton et al., 2014), misinterpreting medication labels (Davis et al., 2006), improper administration of medication, and increased risk of poor health outcomes (Berkman, Sheridan, Donahue, Halpern, & Crotty, 2011). Researchers and clinicians have especially noted the critical importance of functional HL in people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), because DM management requires many self-management skills (Mancuso, 2010; Osborn, Amico, Fisher, Edge, & Fisher, 2010). Although evidence on the relationship between HL and DM management is inconsistent, a systematic review has reported higher HL levels associated with higher self-management activities (Al Sayah, Williams, & Johnson, 2013).

Despite the growing consensus regarding HL’s role in management of chronic conditions (Osborn et al., 2010), significant knowledge gaps persist. One is the lack of a testable theoretical framework with subsequent empirical operationalization of HL to explicate HL mechanisms. We lack longitudinal empirical studies that explore causal relationships between HL and other health outcomes and that identify pertinent moderators and mediators. In addition, HL is a new, evolving scientific field, and many popular HL measures were originally designed to measure global rather than disease-specific HL (Berkman et al., 2011). Empirical results for direct effects of HL on clinical outcomes of glucose control such as A1C levels are inconsistent (Berkman et al., 2011; Moss, 2014). These inconsistencies may have several plausible explanations, but they may be due to a lack of sensitive DM-related HL assessment tools (Macabasco-O’Connell et al., 2011).

Another gap in the literature on HL reflects limited information about linguistic or ethnic minorities. Although such groups are growing rapidly in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013), studies of HL and its role in the management of chronic conditions among them are scarce. For example, Sarkar, Fisher, and Schillinger (2006) reported that adjusting HL did not change self-efficacy and self-management associations in diverse low-income populations in urban areas. In contrast, a study of HL and health status among Asian Americans showed that low HL was significantly associated with self-reported poor health (Sentell, Baker, Onaka, & Braun, 2011).

Korean Americans (KAs) are one of the fastest growing linguistic/ethnic minorities in the United States, the majority of whom are first-generation immigrants. About 80% of U.S. KA adults are foreign-born, compared with 74% of adult Asian Americans and 16% of all U.S. adults (U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). Most Asian American subgroups tend to settle in or near large cities within their own ethnic communities and maintain their ethnic identities. KAs are highly concentrated in five states: California (29.6%), New York (9.0%), New Jersey (5.9%), Texas (5.0%), and Virginia (4.8%; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013).

Many KAs struggle to overcome the linguistic and cultural barriers that adversely affect their HL and their ability to manage chronic conditions such as T2DM. Most first-generation KA adults (90%) are monolingual (Korean only), and more than 70% have trouble understanding medical terminology—even when materials are translated into Korean (Shin & Bruno, 2003). These factors lead to high rates of undetected, undertreated, or poorly managed chronic illnesses, including T2DM, often with costly and tragic consequences (McBean, Li, Gilbertson, & Collins, 2004). In an effort to address the most prominent barrier to adequate T2DM management (Rushforth, McCrorie, Glidewell, Midgley, & Foy, 2016), our team therefore developed and pilot-tested an HL-enhanced behavioral intervention for KAs with T2DM (Kim et al., 2009). Positive outcomes led to a community-based, randomized clinical trial to test the effectiveness of an HL-focused DM self-management intervention (Kim et al., 2015).

Purpose of the Study

Here we report results of our empirical examination of the role of HL in DM management among KAs with T2DM. Utilizing the data for processes and outcomes of our clinical trial of the HL-focused intervention, we characterize mechanisms that underlie HL’s role in DM management.

METHODS

Study Design and Theoretical Framework

Our original open-label, randomized controlled trial was conducted to determine the effectiveness of an HL intervention among KA immigrants with T2DM; data were collected at baseline and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months (Kim et al., 2015). The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board of an academic medical institution located in an eastern region of the United States; written consent was obtained from all study participants. The PRECEDE–PROCEDE model (Green & Kreuter, 1991) provided the study’s main theoretical framework, incorporating several theoretical premises from Braden’s (1990) self-help model. Principles of community-based participatory research informed operational protocols (Israel et al., 2010). Details of recruitment, enrollment, retention, and intervention effects on the primary and secondary outcomes are reported elsewhere (Kim et al., 2015). Community-dwelling KA immigrants with uncontrolled T2DM, measured by A1C 7.0% (53 mmol/mol) or higher, 35–80 years of age, and able to speak and read Korean participated in the study.

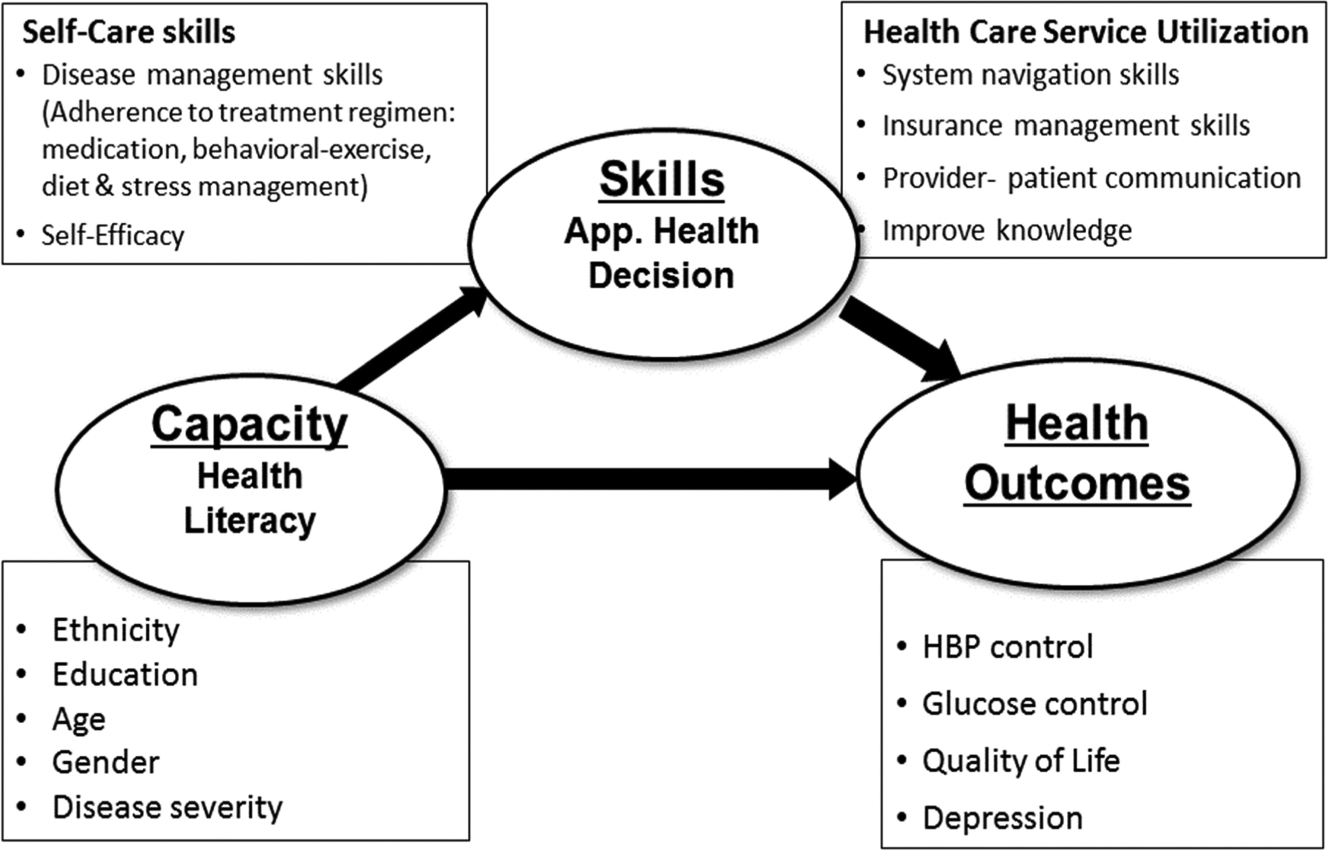

Conceptualization and Operationalization of Health Literacy

The rapidly evolving research on HL offers several definitions (Al Sayah et al., 2013). We have adopted that of Ratzan and Parker (2000): HL is “the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (p. vi). This definition is accepted by the scientific community, including the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, as an operating principle (Berkman et al., 2004). Its conceptual and critical attributes are widely used, because it comprehensively and concisely encompasses characteristics of literacy specific to healthcare. We include the definition’s scientific premises in our theoretical framework for empirical testing (Figure 1), which conceptualizes and operationalizes HL within the management of chronic conditions.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework per AHRQ’s definition of health literacy.

Our model is intended to enhance theoretical understanding of HL as a construct, as well as provide clinical utility to guide intervention development and evaluation. It is based on several assumptions. First, we identify the most critical characteristic of HL in the context of self-management as a “state” or a “skill set” that is fundamentally time-variant; we assume that HL can be changed over time and/or with training. Second, we include theoretically selected correlates of HL (e.g., education, age, disease severity) as moderators of HL, in order to test HL’s construct validity. Third, to make the model useful for evaluating self-management interventions, we hypothesize that the level of HL influences distal outcomes (e.g., glucose control, quality of life [QOL]) through proximal outcomes such as self-care skills, which include self-efficacy and adherence to recommended treatment regimens (e.g., medication, healthy diet and exercise, stress management), and appropriate healthcare utilization skills (e.g., navigating the healthcare system, finding healthcare resources including health insurance, communicating with healthcare providers). Given this conceptual framework, we hypothesize that (a) HL can be improved by a structured literacy intervention and (b) improved HL improves self-care skills, thereby producing desirable health outcomes.

Recruitment, Enrollment, Randomization, and Retention

A total of 250 KA immigrants with uncontrolled T2DM were enrolled in our program and randomized into either the intervention (n = 120) or the control (n = 130) group, with computer software ensuring equivalence between groups on key factors that might influence the primary outcome of A1C (e.g., disease severity, age, body mass index, and gender). A total of 105 individuals in the intervention and 104 controls completed the 12-month program (83.6% retention). Analyses of changes in this study included only participants with complete follow-up data.

The intervention consisted of three components:

Weekly 2-hour didactic classes for 6 weeks, totaling 12 hours. Classes focused on DM etiology, treatment regimens (medication, diet, exercise, and stress management), and training focused on HL and communication with healthcare providers. Instead of giving instructions, we motivated participants’ engagement by incorporating role-playing and utilizing the teach-back method. For example, participants simulated meal planning by using food models and calculating calories of proposed meals. Thirty minutes of each class were devoted to learning DM-related vocabulary and simulating conversations with providers in English.

Monthly telephone counseling. A team of RNs and community health workers contacted and counseled participants regarding medication, diet and exercise adherence, regular check-ups with primary care providers, and overall stress management, using motivational interviewing.

Home monitoring of daily blood sugar. Each participant received a home glucose monitor with sufficient supplies (strips, lancets, etc.). We requested that participants log their daily blood glucose levels in diaries and return copies to us every 3 months. The control group received a shortened version of the education intervention after the program’s completion.

Measurement

Demographic characteristics were collected at baseline. Primary outcomes, including A1C and lipid profiles, were collected at baseline and every 3 months thereafter for up to 12 months. Factors affecting the primary outcomes, including blood pressure and weight, HL, DM-related self-efficacy, social support, DM knowledge, depression, dietary intake (using the 24-hour recall method), and QOL were measured at baseline and at Months 3, 6, and 12.

Health Literacy

We measured two dimensions of HL in the context of DM control: HL knowledge and functional HL. HL knowledge was measured with both the original Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM; Davis et al., 1993) and the diabetes-specific Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (DM-REALM; Kim et al., 2020). The REALM has been used widely for the past 20 years and is known for high clinical utility because of its brevity (Dumenci, Matsuyama, Kuhn, Perera, & Siminoff, 2013) and easy instruction. It is a simple word recognition test of common medical terms. The tool has both a long version (66 items; Murphy, Davis, Long, Jackson, & Decker, 1993) and a short version (8 items; Bass, Wilson, & Griffith, 2003), and it has been translated into many languages and modified to accommo-date special populations (Gordon, Hampson, Capell, & Madhok, 2002; Shea et al., 2004). In addition, the scores can be easily converted to educational grade levels (Murphy et al., 1993). The DM-REALM includes 82 relevant words specifically important to DM, with three levels of difficulty; this scale was developed by our research team and used in our pilot study. Development and validation of the DM-REALM involved three steps. First, we reviewed clinical guidelines and conducted focus groups with experts to generate items. Next, we conducted a psychometric evaluation of the scale in three language versions (English, Spanish, Korean). Last, using item response theory, we identified and removed items with potential cultural bias and duplicate functions to produce shorter versions of the scale. The Korean version used in this study was the original long version that had high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .98) and yielded adequate evidence of convergent validity by significant positive correlations with the functional HL scale (r = .49, p < .001; Kim et al., 2019).

We measured functional HL skills using both the seven-item Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) numeracy subscale (Parker, Baker, Williams, & Nurss, 1995) and Newest Vital Sign (NVS; Weiss et al., 2005). The medication and food labels in these two scales were translated into Korean. Both scales demonstrated acceptable internal consistency reliability, with Cronbach’s alphas of .84 and .75, respectively.

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy in DM management was measured with a scale adapted from the Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Program (Lorig, Sobel, Ritter, Laurent, & Hobbs, 2001). Its eight 10-point, Likert-type items address confidence in DM management with respect to the following: (a) eating meals regularly, every 4–5 hours; (b) following a diabetic diet when eating with people without DM; (c) choosing proper foods (e.g., a snack) when hungry; (d) exercising at least 15–30 minutes a day, four to five times a week; (e) managing blood sugar before, during, and after exercise; (f) understanding how to intervene when blood sugar level is too low or too high; (g) identifying what signs or symptoms warrant a call to the physician; and (h) managing DM so that a normal way of life can continue. In our previous study, the scale was valid and reliable, with an internal consistency coefficient alpha of .85 and test–retest validity of .80 (Kim et al., 2009).

Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes included glucose control (A1C) and QOL. The Johns Hopkins Institute of Clinical and Translational Research laboratory analyzed A1C and lipid profiles (total cholesterol, high- and low-density lipoprotein). To collect blood samples, the lab dispatched a phlebotomist to the Korean Resource Center, a community-based research site. Lab reports were available online within 24 hours, and our research staff summarized the results using a report template in simple Korean and mailed copies to study participants. The report was also used in telephone counseling sessions for those in the intervention group.

Quality of Life

We examined participants’ experiences of DM care and treatment with the DCCT Research Group’s (1988) diabetes QOL (DQOL) measure. This scale’s 15 items address concerns about future effects of DM, social and vocational issues, and the effect of treatment, as well as personal satisfaction with treatment. The DQOL and its four subscales had high degrees of internal consistency (DQOL, Cronbach’s alpha = .84; subscales, Cronbach’s alpha = .66–.92) and excellent test–retest reliability (r = .78–.92). We treated DQOL as a unidimensional scale and used a sum of scores for multivariate analyses. Internal consistency reliability for the scale was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .84).

Data Analysis

We used Stata 12 (StataCorp, 2011) for descriptive analysis (t test, chi-square, etc.) and model testing. In a series of mixed-effects models, we tested changes over time in HL scores, and we used maximum likelihood estimation of structural equation models to test indirect and direct effects of HL on proximal and distal outcomes. This allowed us to combine a confirmatory measurement model of HL and structural path models specifying relationships between HL and process and clinical outcomes of DM self-management simultaneously. The results of the overall intervention on clinical outcomes are detailed elsewhere (Kim et al., 2015); our focus here is to delineate the effect of HL on both process (proximal) and primary clinical (distal) outcomes such as A1C and QOL. Only participants who remained in the program for 12 months (n = 209) were included in the analysis.

RESULTS

The majority of participants were middle aged (average = 58.7 years, SD = 8.4); more men (59.1%) than women completed the study. Most were married (89.5%), and 59.3% were working full/part time. More than half (63.2%) lived in their own homes, with an average of one child and an average monthly income of $3,780; about two thirds (67.7%) reported a comfortable standard of living. The present sample was similar to estimates for all KAs with regard to monthly median income ($3,750; U.S. Census Bureau, 2013). On average, participants had completed 13.4 years (SD = 3.0) of education before they immigrated to the United States and had lived in the United States for an average of 23.4 years (minimum/maximum, 0.1–53.0; median = 25.1). At baseline, average A1C levels were 8.9 mmol/mol (intervention group, 7–11) and 8.8 mmol/mol (control group, 7–15); this difference was not statistically significant. In major demographic characteristics, the intervention and control groups were almost identical.

Characteristics of HL

At baseline, participants’ mean REALM score (minimum/maximum, 0–66) was 32.1 (SE = 1.5), indicating a third to sixth grade level of HL knowledge. The mean DM-REALM (minimum/maximum, 0–82) was 51.3 (SE = 1.7), 7.3 points above the scale’s midpoint. Mean comprehension was 15.3 (SE = 0.6; range, 0–28), mean TOFHLA functional HL was 4.2 (SE = 0.2; minimum/maximum, 0–7), and mean NVS functional HL was 1.7 (SE = 0.1; minimum/maximum, 0–6). Overall HL scores in these KA immigrants with T2DM were lower than those previously reported for non-Hispanic Whites (Kirk et al., 2012; Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, & Paulsen, 2006). Compared with non-Hispanic Whites with T2DM, this sample tended to have lower functional HL (adequate level, 37%) than did non-Hispanic Whites (adequate level, 50.2%). The portion of intermediate and proficient functional HL measured with TOFHLA in our sample was also lower than in the general U.S. population (51% vs. 72%).

The four HL measures were highly correlated with each other, and all correlations were statistically significant. The correlation between REALM and DM-REALM was highest (r = .91, p < .001), followed by that for the TOFHLA (r = .68, p < .001) and NVS (r = .47, p < .001) numeracy measures. Among socio-demographic variables, age, years of schooling, gender, level of financial comfortability, and years of U.S. residency were all correlated with HL measures. Overall, those who were younger (REALM, r = −.09, p < .01; DM-REALM, r = −.11, p < .05; TOFHLA, r = −.24, p < .001; NVS, r = −.26, p < .001), more educated (REALM, r = .50, p < .001; DM-REALM, r = .53, p < .001; TOFHLA, r = .29, p < .001; NVS, r = .15, p < .05), financially stable (REALM, r = .19, p < .01; DM-REALM, r = .17, p < .01), and had lived for a longer time as a U.S. resident (REALM, r = .22, p < .001; DM-REALM, r = .26, p < .001; TOFHLA, r = .22, p < .01; NVS, r = .21, p < .01) showed the highest HL scores (Table 1). At baseline, the HL measures were not significantly correlated with other distal or proximal outcomes.

TABLE 1.

Health Literacy Characteristics at Baseline

| Instrument | REALM (0–66) | DM-REALM (0–82) | COMP (0–28) | TOFHLA (0–7) | NVS (0–6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | 32.1 (1.5) | 51.3(1.7) | 15.3 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.2) | 1.7 (0.1) |

| Correlations | |||||

| DM-REALM | .91*** | - | |||

| TOFHLA | .68*** | .68*** | .64*** | - | |

| NVS | .47*** | .49*** | .44*** | .60*** | - |

| Demographic | |||||

| Age, years | −0.09** | −0.11* | −0.10*** | −2.4*** | −2.6*** |

| Education | 0.50*** | 0.53*** | .45*** | .29*** | 0.15* |

| Gender (male) | 0.19** | 0.17* | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Comfortable living | 0.19** | 0.17** | 0.20** | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Years in USA | 0.22*** | 0.26*** | 0.32*** | 0.22** | 0.21** |

Note. SE = standard error; REALM = Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine; DM-REALM = diabetes-specific REALM; COMP = comprehension scale; TOFHLA = Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults, numeracy items; NVS = Newest Vital Sign, numeracy.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

To test the hypothesis that a DM-specific, relatively short-term HL education intervention would significantly improve HL in a sample of KAs with T2DM, we used a series of t tests on scores of HL measures for the intervention and control groups, with Bonferroni correction to address any potential for significant results due to chance. We also used a series of mixed-effects models to test temporal effects of the intervention on HL scores (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Health Literacy Scores Over Time

| Instrument | Baseline | Month 3 | Month 6 | Month 12 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REALM (0–66), mean (SE) | 32.1 (1.5) | 33.9 (1.5) | 34.4(1.6) | 36.1 (1.6) | |||

| Intervention (I) | 34.2 (2.1) | 38.2 (2.1) | 38.5 (2.1) | 40.5 (2.2) | |||

| Control (C) | 30.0(2.1) | 29.6 (2.1) | 30.3 (2.1) | 31.5(2.2) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | 4.2 (3.0) | 8.6 (3.0) | ** | 8.2 (3.1) | ** | 9.0 (3.1) | ** |

| Changes from baseline | |||||||

| Intervention (I) | — | 4.0(1.1) | *** | 4.3 (1.1) | *** | 6.3 (1.1) | *** |

| Control (C) | — | −0.5 (1.1) | 0.3 (1.1) | 1.5 (1.1) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | — | 4.5 (1.5) | ** | 4.0 (1.5) | ** | 4.8(1.5) | *** |

| DM-REALM (0–82), mean (SE) | 51.3(1.7) | 55.5 (1.7) | 55.5(1.7) | 56.9(1.8) | |||

| Intervention (I) | 54.2 (2.1) | 61.3 (2.2) | 61.6 (2.1) | 62.9(2.1) | |||

| Control (C) | 48.4 (2.5) | 49.6 (2.6) | 49.4 (2.6) | 50.8 (2.7) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | 5.7 (3.3) | 11.7(3.4) | *** | 12.1 (3.4) | *** | 12.1(3.4) | *** |

| Changes from baseline | |||||||

| Intervention (I) | — | 7.2 (1.5) | *** | 7.5 (1.5) | *** | 8.4(1.5) | *** |

| Control (C) | — | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.0 (1.1) | 2.4 (1.1) | * | ||

| Diff (I - C) | — | 6.0 (1.5) | *** | 6.4 (1.5) | *** | 6.4(1.5) | *** |

| COMP (0–28), mean (SE) | 15.3 (0.6) | 17.9 (0.6) | 18.2 (0.6) | 18.7 (0.6) | |||

| Intervention (I) | 16.5 (0.9) | 20.8 (0.8) | 20.9 (0.8) | 21.3 (0.8) | |||

| Control (C) | 14.2 (0.9) | 14.9 (0.9) | 15.5 (0.9) | 16.1 (0.9) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | 2.3 (1.3) | 5.9 (1.2) | 5.4 (1.2) | 5.1 (1.2) | |||

| Changes from baseline | |||||||

| Intervention (I) | — | 4.3 (0.4) | *** | 4.4 (0.4) | *** | 4.8 (0.4) | *** |

| Control (C) | — | 0.7 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.4) | ** | 1.9 (0.4) | *** | |

| Diff (I - C) | — | 3.7 (0.6) | *** | 3.2 (0.6) | *** | 2.9 (0.6) | *** |

| TOFHLA (0–7), mean (SE) | 4.2 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.4 (0.2) | 4.7 (0.3) | |||

| Intervention (I) | 4.3 (0.3) | 4.8 (0.2) | 4.6 (0.2) | 4.9 (0.2) | |||

| Control (C) | 4.1 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.3) | 4.4 (0.3) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.3) | * | 0.5 (0.3) | 0.5 (0.3) | ||

| Changes from baseline | |||||||

| Intervention (I) | — | 0.5 (0.2) | * | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.7 (0.2) | ** | |

| Control (C) | — | −0.1 (0.2) | −0.0 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | — | 0.6 (0.3) | * | 0.4 (0.3) | 0.4 (0.3) | ||

| NVS (0–6), mean (SE) | 1.7 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.1) | 2.3 (0.1) | 2.7 (0.2) | |||

| Intervention (I) | 1.7 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | 2.6 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.2) | |||

| Control (C) | 1.7 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.2) | |||

| Diff (I - C) | 0.0 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.3) | ** | 0.6 (0.3) | * | 0.7 (0.3) | * |

| Changes from baseline | |||||||

| Intervention (I) | — | 0.6 (0.2) | ** | 0.9 (0.2) | *** | 1.3 (0.2) | *** |

| Control (C) | — | −0.1 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.6 (0.2) | * | ||

| Diff (I - C) | — | 0.7 (0.3) | * | 0.6 (0.3) | * | 0.7 (0.3) | * |

The overall direction of change was positive in all of the HL measures, and most changes were statistically significant. With the exception of the NVS—for which the biggest changes occurred at the end of intervention—changes occurred during the first 3 months and were sustained through-out the project period. The intervention and control groups had roughly similar levels of HL (i.e., not statistically different) at baseline on all five measures, but improvements in the intervention group were much greater. The differences between the two groups in improvement from baseline were all statistically significant, except for the changes in TOFHLA scores at Months 6 and 12. The gaps in HL improvements between the two groups expanded when HL scores were adjusted by controlling for the effects of other correlated variables, including age, years of education, gender, financial stability, and years of U.S. residency (Figure 2). The statistically significant changes within the first 3-month period, especially in the intervention group, support our hypothesis that HL is a “state variable” that can be changed by an intervention within a relatively short time.

FIGURE 2.

Changes of DMHL scores over time with 95 CIs.

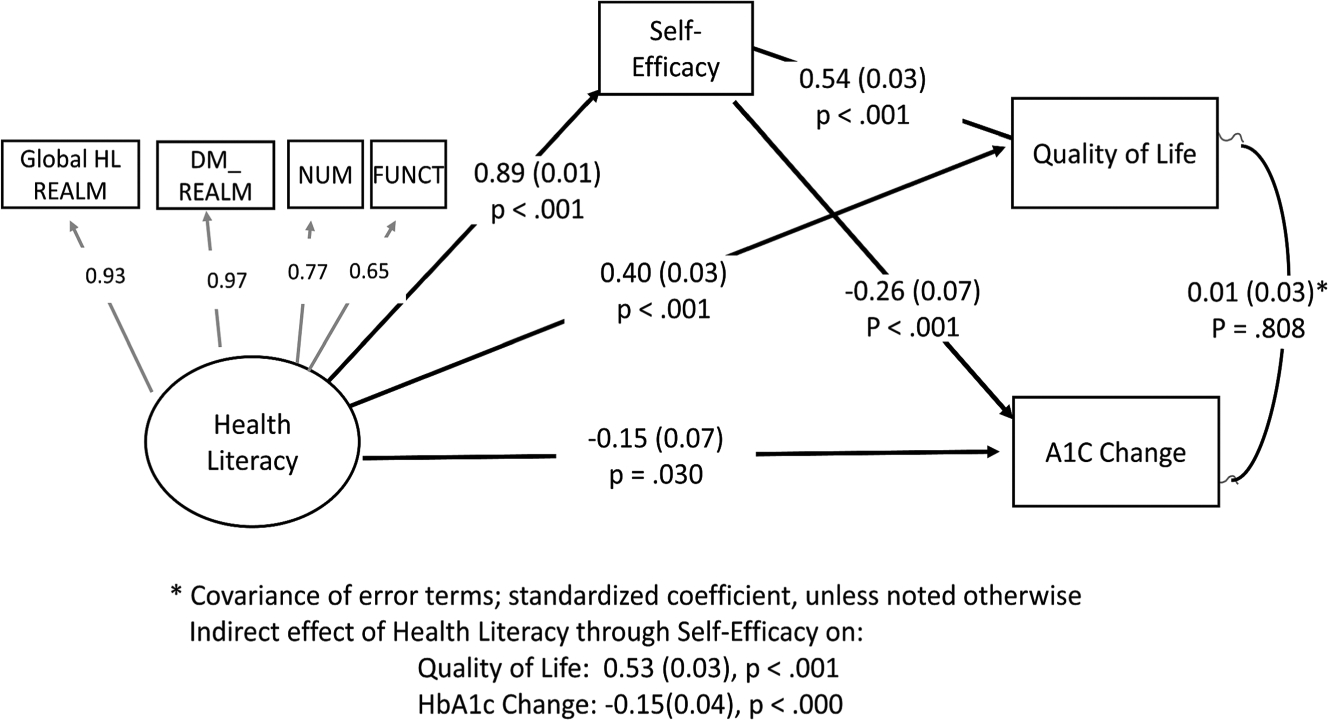

To delineate the underlying mechanism of HL changes’ positive influence on both proximal (e.g., self-care skills, self-efficacy) and distal (A1C, QOL) outcomes, we constructed a structural equation model. Based on the conceptual framework and operationalization of HL as a capacity, we postulated that HL would influence distal outcomes both directly and indirectly, but that the indirect effects acting through proximal outcomes would be stronger than direct effects on distal outcomes. Overall HL was treated as a latent variable; the measurement model consisted of five HL scales for different HL dimensions. The dependent variables were DM-specific QOL and change in A1C level (%) from baseline (Table 2).

Figure 3 depicts structural relationships between HL and the distal outcomes of A1C and QOL and the proximal outcome of self-efficacy. The comparative fit index (Rigdon, 1996) was .96, and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) was .111 (95% CI [.007, .126], p < .001). The latent factor, HL, had five observed indicators, and HL was significantly correlated with those indicators; the correlation with DM-REALM was the highest (.97), followed by REALM (.93), TOFHLA (.77), and NVS (.65).

FIGURE 3.

Path model among health literacy, self-efficacy, quality of life and HbA1c change.

The direct effect of HL on self-efficacy was statistically significant (b = .172, SE = .035, p < .001), but it was not significant for A1C change (b = −.004, SE = .035, p = .908) or QOL (b = .057, SE = .033, p < .083). However, the indirect effects of HL, through self-efficacy, on A1C change (b = −.001, SE = .0004, p = .019) and on QOL (b = .028, SE = .006, p < .001) were statistically significant. The direct effects of self-efficacy on A1C change (b = −.09, SE = .034, p = .008) and QOL (b = .367, SE = .30, p < .001) were also statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have examined the role of HL in DM management among KAs with T2DM. This sample suffered from low HL, with education attainment and level of acculturation as significant correlates. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies in which researchers have identified that people with low educational levels—including older adults and first-generation immigrants whose primary language is not English—are among the most vulnerable groups affected by low HL (Easton, Entwistle, & Williams, 2010). Low HL is often a source of health disparities, and among people with chronic illness, it is a major barrier to successful management of chronic conditions such as T2DM (Bailey et al., 2014).

Our study demonstrates that HL knowledge and skills can be changed within a relatively short time (12 weeks), with a continually improving trajectory as a result of intervention. Improved HL was a strong predictor of improved self-care skills, including self-efficacy, which ultimately improved primary outcomes by lowering A1C and improving QOL.

Our findings, however, should be interpreted with caution regarding generalization. Our target population, KA immigrants with T2DM, was highly motivated to participate in this intervention because few linguistically and culturally tailored interventions were available, and these first-generation immigrants were experiencing negative consequences of limited HL such as loss of self-confidence and social isolation. In addition, the psychological and behavioral outcomes of the intervention might have been influenced by other intervention components, such as the self-monitoring of glucose and emotional support provided by monthly telephone counseling.

The sample size (n = 209) was relatively small for path analyses, and internal consistency of one DQOL subscale was low (.66). It is plausible that the parameters for this data set were underestimated due to the potential issue of power. Finally, the RMSEA failed to reach the threshold level for a good fit. Although the comparative fit index was acceptable, the RMSEA indicated less than adequate fitness of the data to the model.

Nevertheless, this study’s findings have significant scientific implications. To the best of our knowledge, no other interventions have been designed to change HL levels in order to improve self-care skills for the successful management of DM. We believe that the improvement in HL in this study is a direct result of our educational intervention, because the other intervention components (monitoring and counseling) did not contain HL improvement modules. In addition, this study provided a unique ground for testing several causal relationships among relevant factors by means of a longitudinal design with repeated measures. We measured all indicators of interest, including all five HL measures. With these repeated measures of HL and other indicators, we were able to answer two critical issues in the HL field: (a) whether individual HL is improvable through intervention and (b) identification of pathways through which HL affects health outcomes in the context of chronic disease management.

HL can be improved if proper interventions are designed and implemented; self-care skills such as self-efficacy mediate the relationship between HL and health outcomes. This finding has important clinical implications for chronic disease management in populations with limited HL.

Conclusion

Our targeted HL intervention had a positive influence on self-care skills such as knowledge, self-efficacy, adherence, and, ultimately, glucose control; it improved the overall capacity of individuals to effectively manage their chronic conditions.

HL is often regarded as a missing link in explaining relationships among individual characteristics, known psychosocial variables, and chronic disease management behaviors, particularly in linguistic minority groups that experience significant health disparities. Given growing health disparity gaps in DM management among ethnic/linguistic minority populations, researchers should consider educational interventions that directly influence HL as a viable option. Studies that further validate the findings of this study are warranted to move translation science forward to improve HL in ethnic/linguistic minority populations.

Acknowledgments

This research reported in this publication was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R18DK083936). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the substantial editorial support provided by Dr. John Bellquist at the Cain Center for Nursing Research and the Center for Transdisciplinary Collaborative Research in Self-Management Science (P30, NR015335) at The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing.

The research protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Institutional Review Board, and written consent was obtained from all study participants.

Footnotes

Although this paper is not reporting outcomes of clinical trial, the data used in the analysis were obtained from an intervention trial registered in clinical trial. gov registry (NCT01264796). Date of registration: Dec 22, 2010, https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01264796?term=NCT01264796&rank=1

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Miyong T. Kim, School of Nursing, The University of Texas at Austin..

Kim B. Kim, Korean Resource Center, Ellicott City, Maryland..

Jisook Ko, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio..

Nicole Murry, School of Nursing, The University of Texas at Austin..

Bo Xie, School of Nursing, The University of Texas at Austin..

Kavita Radhakrishnan, School of Nursing, The University of Texas at Austin..

Hae-Ra Han, Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing, Baltimore, Maryland..

REFERENCES

- Al Sayah F, Williams B, & Johnson JA (2013). Measuring health literacy in individuals with diabetes: A systematic review and evaluation of available measures. Health Education & Behavior, 40, 42–55. doi: 10.1177/1090198111436341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, Elasy T, Herr H, Kaphingst K, … Schillinger D (2014). Update on health literacy and diabetes. Diabetes Educator, 40, 581–604. doi: 10.1177/0145721714540220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass PF 3rd, Wilson JF, & Griffith CH (2003). A shortened instrument for literacy screening. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18, 1036–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.10651.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP, Sheridan SL, Lohr KN, Lux L, … Bonito AJ (2004). Literacy and health outcomes: Summary In AHRQ evidence report summaries. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, & Crotty K (2011). Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155, 97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden CJ (1990). Learned self-help response to chronic illness experience: A test of three alternative learning theories. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 4, 23–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JZ, Hsu HC, Tung HJ, & Pan LY (2013). Effects of health literacy to self-efficacy and preventive care utilization among older adults. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 13, 70–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, & Crouch MA (1993). Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Family Medicine, 25, 391–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF III, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, & Parker RM (2006). Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Annals of Internal Medicine, 145, 887–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DCCT Research Group (1988). Reliability and validity of a diabetes quality-of-life measure for the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT). Diabetes Care, 11, 725–732. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.9.725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumenci L, Matsuyama RK, Kuhn L, Perera RA, & Siminoff LA (2013). On the validity of the shortened Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) Scale as a measure of health literacy. Communication Methods and Measures, 7, 134–143. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2013.789839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton P, Entwistle VA, & Williams B (2010). Health in the “hidden population” of people with low literacy: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Public Health, 10, 459. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M-M, Hampson R, Capell HA, & Madhok R (2002). Illiteracy in rheumatoid arthritis patients as determined by the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) score. Rheumatology, 41, 750–754. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.7.750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, & Kreuter MW (1991). Health promotion planning: An educational and environmental approach (2nd ed.). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Griffey RT, Kennedy SK, McGownan L, Goodman M, & Kaphingst KA (2014). Is low health literacy associated with increased emergency department utilization and recidivism? Academic Emergency Medicine, 21, 1109–1115. doi: 10.1111/acem.12476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard DH, Gazmararian J, & Parker RM (2005). The impact of low health literacy on the medical costs of Medicare managed care enrollees. American Journal of Medicine, 118, 371–377. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR, Schulz AJ, McGranaghan RJ, Lichtenstein R, … Burris A (2010). Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.170506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Han HR, Song HJ, Lee JE, Kim J, Ryu JP, & Kim KB (2009). A community-based, culturally tailored behavioral intervention for Korean Americans with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator, 35, 986–994. doi: 10.1177/0145721709345774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Kim KB, Huh B, Nguyen T, Han H-R, Bone LR, & Levine D (2015). The effect of a community-based self-help intervention: Korean Americans with Type 2 diabetes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49, 726–737. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MT, Li Z, Nguyen T, Ko J, & Kim KB, Han HR (In press). Development of DM focused print HL scale using rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine model: (DM-REALM). HLRP: Health Literacy Research and Practice. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk JK, Grzywacz JG, Arcury TA, Ip EH, Nguyen HT, Bell RA, … Quandt SA (2012). Performance of health literacy tests among older adults with diabetes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27, 534–540. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1927-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, & Paulsen C (2006). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006–483). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, & Hobbs M (2001). Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Effective Clinical Practice, 4, 256–262. Retrieved from http://ecp.acponline.org/novdec01/lorig.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macabasco-O’Connell A, DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Baker DW, Schillinger D, … Pignone M (2011). Relationship between literacy, knowledge, self-care behaviors, and heart failure-related quality of life among patients with heart failure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 979–986. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1668-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancuso JM (2010). Impact of health literacy and patient trust on glycemic control in an urban USA population. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12, 94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00506.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBean AM, Li S, Gilbertson DT, & Collins AJ (2004). Differences in diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality among the elderly of four racial/ethnic groups: Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Diabetes Care, 27, 2317–2324. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton CD, Kripalani S, Cawthon C, Mion LC, Wallston KA, & Roumie CL (2014). Association of health literacy with elevated blood pressure: A cohort study of hospitalized patients. Medical Care, 52, 346–353. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss TR (2014). The impact of health literacy on clinical outcomes for adults with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Advances in Diabetes and Metabolism, 2, 10–19. Retrieved from http://www.hrpub.org/journals/article_info.php?aid=1698 [Google Scholar]

- Murphy PW, Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, & Decker BC (1993). Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM): A quick reading test for patients. Journal of Reading, 37, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Osborn CY, Amico RK, Fisher WA, Edge LE, & Fisher JD (2010). An information-motivation-behavioral skills analysis of diet and exercise behavior in Puerto Ricans with diabetes. Journal of Health Psychology, 15, 1201–1213. doi: 10.1177/1359105310364173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, & Nurss JR (1995). The Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults: A new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 10, 537–541. doi: 10.1007/bf02640361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratzan SC, & Parker RM (2000). Introduction In RatzanR SC. ParkerC M. Selden R & Zorn M (Eds.), National Library of Medicine current bibliographies in medicine: Health literacy (NLM Pub. No. CBM 2000–1). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon EE (1996). CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 3, 369–379. doi: 10.1080/10705519609540052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rushforth B, McCrorie C, Glidewell L, Midgley E, & Foy R (2016). Barriers to effective management of Type 2 diabetes in primary care: Qualitative systematic review. British Journal of General Practice, 66, e114–e127. doi: 10.3399/bjgp16X683509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar U, Fisher L, & Schillinger D (2006). Is self-efficacy associated with diabetes self-management across race/ethnicity and health literacy? Diabetes Care, 29, 823–829. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.04.06.dc05-1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell T, Baker KK, Onaka A, & Braun K (2011). Low health literacy and poor health status in Asian Americans and Pacific islanders in Hawai’i. Journal of Health Communication, 16, 279–294. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.604390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea JA, Beers BB, McDonald VJ, Quistberg DA, Ravenell KL, & Asch DA (2004). Assessing health literacy in African American and Caucasian adults: Disparities in Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) scores. Family Medicine, 36, 575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin HB, & Bruno R (2003, October). Language use and English-speaking ability: 2000 (Census 2000 Brief). Washington, DC: U.S: Census Bureau; Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-29.pdf [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2011). Stata statistical software: Release 12. College Station, TX: Author. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2013). American Community Survey (ACS): 2009–2013 ACS 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/technical-documentation/table-and-geography-changes/2013/5-year.html [Google Scholar]

- Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, … Hale FA (2005). Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: The Newest Vital Sign. Annals of Family Medicine, 3, 514–522. doi: 10.1370/afm.405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JR, Holmes GM, DeWalt DA, Macabasco-O’Connell A, Bibbins-Domingo K, Ruo B, … Pignone M (2013). Low literacy is associated with increased risk of hospitalization and death among individuals with heart failure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 1174–1180. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2394-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]