CONSPECTUS:

Membrane potential is a fundamental biophysical property maintained by every cell on earth. In specialized cells like neurons, rapid changes in membrane potential drives the release of chemical neurotransmitters. Coordinated, rapid changes in neuronal membrane potential across large numbers of interconnected neurons forms the basis for all of human cognition, sensory perception, and memory. Despite the importance of this highly orchestrated and distributed activity, the traditional method for recording membrane potential is through the use of highly invasive, single-cell electrodes that offer only a small glimpse of the total activity within a system. Fluorescent dyes that change their optical properties in response to changes in biological voltage have the potential to provide a powerful complement to traditional, electrode-based methods of inquiry. Voltage-sensitive fluorescent indicators would allow the direct observation of membrane potential changes, significantly expanding our ability to monitor membrane potential dynamics in living systems.

Towards this end, we have initiated a program to design, synthesize, and apply voltage-sensitive fluorophores that report on membrane potential dynamics with high sensitivity and speed. The basis for this optical voltage sensing is membrane potential-dependent photoinduced electron transfer (PeT). Voltage-sensitive fluorophores, or VoltageFluors, possess a fluorophore, conjugated molecular wire, and aniline donor. At resting potentials, in which the cell has a hyperpolarized, or negative potential, relative to the outside of the cell, PeT from the aniline donor is enhanced and fluorescence diminished. At depolarized potentials, the membrane potential decreases the rate of PeT, allowing an increase in fluorescence. We show that a number of different fluorophores, molecular wires, and aniline donors can be employed to generate fast and sensitive VoltageFluor dyes. Multiple lines of evidence point to a PeT-based mechanism for voltage sensing, delivering fast response kinetics (~25 ns), good sensitivity (>60% ΔF/F), compatibility with two-photon illumination, excellent signal-tonoise, and the ability to detect neuronal and cardiac action potentials in single trials. In this account, we provide an overview of the challenges facing the design of fluorescent voltage indicators. We trace the development of molecular wire-based fluorescent voltage indicators within our group, beginning from fluorescein-based VoltageFluor to long-wavelength indicators that use modern fluorophores like silicon rhodamine and carbofluorescein. We examine design principles for PeT-based voltage indicators, showcase the use of our recent indicators for two-photon voltage imaging in intact brains, and explore the development of hybrid indicators that can localize to genetically defined cells. Finally, we highlight outstanding challenges to and opportunities for voltage imaging.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Membrane potential is a unique biophysical property maintained by every cell on earth. The importance of membrane potential is widely recognized in the context of specialized organs like the brain and the heart. Yet, our understanding of the ways in which membrane potential, and its coordinated, rapid changes across large numbers of neurons, gives rise to fundamental phenomena like cognition, sensation, and memory remain incomplete. This is due, in part, to our inability to record voltage dynamics across large numbers of cells at high speed. Traditional methods of monitoring biologically relevant voltage signals rely on electrodes for single-cell, patch-clamp electrophysiology. Despite excellent sensitivity and high temporal resolution, whole-cell electrophysiological techniques are destructive and suffer from low throughput and poor spatial resolution.

Alternatively, fluorescence-based optical sensors are promising complements to visualize voltage changes in a non-invasive and high throughput manner. Organic dye molecules have long been employed as indicators of membrane potential.1–2 Traditional voltage-sensing dye molecules fall into two broad categories.3–4 “Fast” dyes have response kinetics able to track neuronal action potentials but with generally lower sensitivity. These dyes take advantage of electrochromic mechanisms5–6 or excited state proton transfer7 to achieve voltage sensitivity.

On the other hand, slow dyes depend on the movement of a lipophilic ion through the membrane to achieve sensitivity.8 These dyes generally show a larger fractional change in fluorescence but can perturb membrane capacitance and do not possess response kinetics able to measure fast spiking events. More details on voltage-sensing mechanisms can be found in reviews by our group and others.2–4, 9 More recently, genetically encoded fluorescent indicators have emerged as another useful approach for monitoring membrane potentials.10–13

We have initiated a program to develop voltage-sensitive fluorophores with high response kinetics and high voltage sensitivity to enable single trial detection of action potentials and voltage dynamics in living cells. Our hypothesis is that this new class of voltage-sensitive fluorophores, or VoltageFluors, would utilize photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) as the trigger to transduce changes in membrane potential into changes in fluorescence intensity (Figure 1).14–15 VoltageFluors or VF dyes, consist of a fluorescent dye fused with a lipophilic and electron-rich molecular wire that allows VF dyes to localize to plasma membrane for voltage sensing (Figure 1). Modulated by the transmembrane electric field, the rate of photo-induced electron transfer (PeT) from the electron-rich donor moiety affects the extent of fluorescence quenching of the fluorescent reporter (Figure 1). Depolarization slows down the PeT process and attenuates the quenching effect, resulting in an increase in fluorescence. The mechanism of VF dyes to detect voltage changes relies on movement of electrons that must intercept the excited state chromophore prior to fluorescence (nanosecond timescale), which is orders of magnitude faster than millisecond-duration neuronal action potentials. In addition to excellent response kinetics, the chemical structures can be readily modified to achieve variations in the color, sensitivity, photo-stability and other photo-physical properties to create a wide range of sensors for different applications.27–31 Below, we recount some of the lessons and insights we have gained in exploring the development of voltage-sensitive fluorophores.

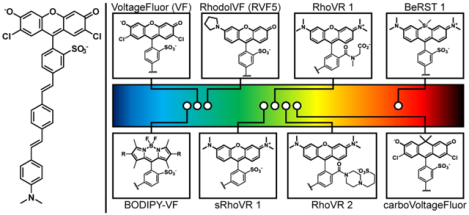

Figure 1.

A glowing and growing palette of Voltage-sensitive Fluorophores (VoltageFluors). (left) Proposed mechanism of voltage sensing in VoltageFluor dyes. At hyperpolarizing potentials, photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) from an electron rich aniline group is enhanced by the transmembrane potential, quenching fluorescence. Upon depolarization, the rate of PeT decreases, resulting in fluorescence enhancement. (middle) Prototypical VoltageFluor, VF2.1.Cl. (right) Representative fluorophores that have been incorporated into Voltage-sensitive Fluorophore scaffolds. The location of the circle in the rainbow spectrum indicates the approximate excitation wavelength required for the dye. Abbreviations: RhoVR = Rhodamine Voltage Reporter; BeRST = Berkeley Red Sensor of Transmembrane potential. sRhoVR is sulfonated RhoVR.

Results

Green dyes, including VF dyes, BODIPY-VFs, fluoreneVFs and dsVFs

Initial studies16–17 revealed that a phenylenevinylene molecular wire, coupled to a sulfonofluorescein reporter, provided a prototypical VoltageFluor dye, VF2.1.Cl, with fast response kinetics, good voltage sensitivity (~27% ΔF/F per 100 mV), and the ability to track neuronal action potentials in single trials. Subsequent studies17 examined the relationship between the electron affinities of fluorescent reporter and aniline donor. Synthesis and characterization of a suite of fluorescein-based VF dyes revealed that voltage sensitivity in these indicators relies on the presence of an aniline donor. Consistent with a PeT-based mechanism of sensing, the electron affinities of the donor/acceptor within the molecular wire profoundly influence voltage sensitivity, with voltage sensitivities ranging from 5% to 49% ΔF/F per 100 mV in HEK cells. Further corroborating a PeT-based mechanism of voltage sensing, response kinetic of VF dyes are exceptionally fast, limited by the charging of cellular membranes.16 More recent studies employ nano-second electrical pulses with ultra-fast streak cameras to estimate the response kinetics of VF-type dyes at approximately 25 ns.18 We also recently showed that the fluorescence lifetime of VF dyes varies with membrane potential, providing additional support for a PeT-based mechanism of sensing.19 New indicators like VF2.1(OMe).H, with a sensitivity of 48% ΔF/F and improved cellular brightness compared to the chloro-substituted analog, allowed investigation of functional coupling across multiple neurons imaged simultaneously in intact, ex vivo leech preparations,17 linking the topology of neuronal circuits to activity.20 Subsequent studies coupled the use of improved VF dye VF2.1(OMe).H to innovative double-sided microscopies for comprehensive neuronal profiling across large numbers of neurons in intact leech ganglia.21

Voltage sensing via molecular wires can be extended to other fluorophores and molecular wires (Figure 2). Consistent with a PeT-based voltage sensing framework, BODIPY fluorophores also function as voltage-sensitive indicators when coupled to a phenylenevinylene molecular wire scaffold.22 As with fluorescein-based indicators, appropriate tuning of fluorophore / aniline donor electron densities is required for maximal voltage sensitivity. Combinations of electron poor fluorophores with electron-rich donors give only weakly sensitive indicators; conversely, electron-rich fluorophores and electron-poor donors are also not very voltage sensitive. In a complementary study, we investigated the use of fluorene molecular wires for voltage sensing.23 When integrated into a fluorophore-donor unit, fluorene molecular wires produce effective fluorescent voltage indicators. Fluorene-based VoltageFluor 2 (or fVF2, Figure 2) displays good voltage sensitivity (10% ΔF/F per 100 mV) and can be used to monitor cardiac action potentials in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSCCMs). Intriguingly, we find that fVF2 displays improved longterm photostability and minimal phototoxicity compared to VF2.1.Cl. Fluorene molecular wires may be an important method for mitigating phototoxicity that can be associated with long term imaging. Together, these studies highlight the versatility of the molecular wire-based voltage sensing approach – it can be extended to different classes of fluorophores and molecular wires.

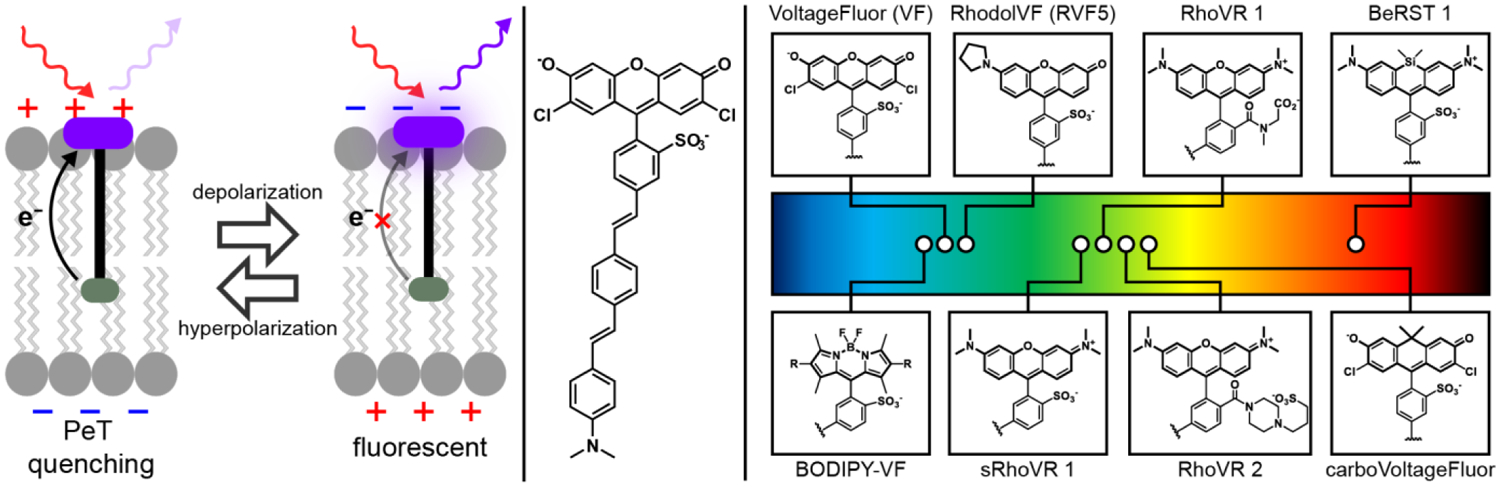

Figure 2.

Structure of selected PeT-based voltage-sensitive fluorophores. Abbreviations: RhoVR is Rhodamine Voltage Reporter. BeRST is Berkeley Red Sensor of Transmembrane potential. RVF5 is Rhodol VoltageFluor 5. sRhoVR is sulfonated RhoVR. VF-EX2 is VoltageFluor activated by esterase expression.

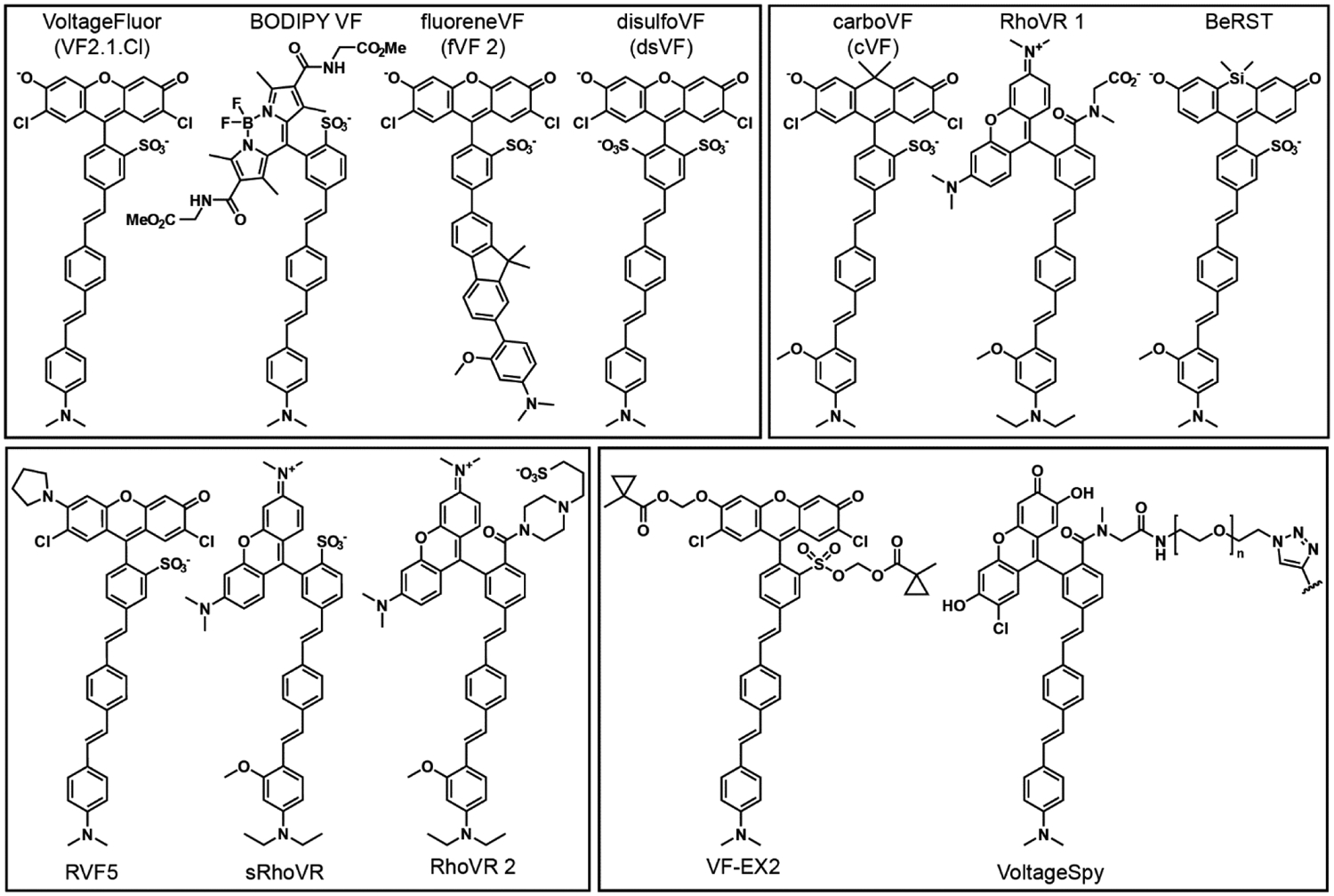

To further drive our understanding of the mechanisms underlying voltage sensing in VF dyes, we used molecular modeling to ask how VF dyes orient in plasma membranes.24 We used molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to calculate the tilt angle, or degree of displacement away from membrane normal and find that a typical VF dye shows significant flexibility within the plasma membrane (Figure 3a–c). The calculations hinted at a structure—containing a symmetrical sulfonation pattern—that would resolve this rather large tilt angle, reducing it to 19° (Figure 3b–c). We hypothesized that the better alignment between the principal component of VF and the transmembrane electric field would result in an approximate 16% increase in voltage sensitivity, based solely on geometry. We then confirmed this computational result by synthesizing new, doubly-sulfonated VF dyes (dsVFs, Figure 2), enabling pairwise, experimental comparisons of monosulfoVF and dsVF dyes which differed only in their sulfonation pattern. In all cases, voltage sensitivity increased with the dsVF dye (Figure 3d), with an average increase of 19%: in close agreement with the 16% predicted by MD simulation. This result not only validates our computational model of VF dyes in a lipid membrane, but provided the most sensitive PeT-based VF to date, dsVF2.2(OMe).Cl, with a voltage sensitivity of 63% ΔF/F per 100 mV (Figure 3e–f). We show that with this increased sensitivity, dsVF2.2(OMe).Cl can readily monitor spontaneous activity in mid-brain dopaminergic neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells (Figure 3g–h).24–27 More generally, the new doubly-sulfonated fluorophores that we disclosed here (i.e. not attached to voltage-sensing domain) are useful in their own right for a number of imaging and labeling applications, on account of their isomeric purity, high quantum yield, and excellent water solubility.

Figure 3.

Doubly-sulfonated VoltageFluor dyes show improved performance compared to mono-sulfo VoltageFluor indicators. Snapshots of MD simulations in POPC lipid bilayers show a) msVF and b) dsVF. Yellow arrows indicate principal components. c) Plot of probability density vs angle of displacement between the third principle component (the long axis) of VF dyes and the membrane normal. d) Comparison of fractional voltage sensitivity (ΔF/F) per 100 mV in HEK cells between msVF (blue) and matched dsVF (red) dyes. e) Confocal imaging of HEK cells stained with dsVF2.2(OMe).Cl reveals membrane-associated fluorescence. Scale bar is 20 μM. f) A plot of % ΔF/F vs final membrane potential (mV), summarizing data from eight separate cells, reveals a voltage sensitivity of approximately 63% per 100 mV (±1.6%). Error bars are ± SEM. g) Confocal images of rat hippocampal neurons stained with 500 nM dsVF2.2(OMe).Cl. Scale bar is 20 μM. h) Percentage change in fluorescence vs time for human pluripotent stem cell-derived mid-brain dopaminergic neurons (mDA). All traces have been bleach corrected and are unfiltered.

Red dyes, including RhoVR, carboVF, and BeRST

Although members of the VF, fVF, and BODIPY-VF family exhibit high voltage sensitivity, their excitation and emission profiles in the cyan / blue range introduces several problems. First, higher energy blue light causes more tissue damage, scatters more than longer wavelengths, and is absorbed by endogenous chromophores. Secondly, many of the best optical indicators and actuators use blue excitation light, prohibiting their simultaneously usage with voltage indicators that use similar wavelengths. To address this challenge, we have developed a suite of voltage-sensitive fluorophores whose excitation spectra extend into the far-red region of the visible spectrum.

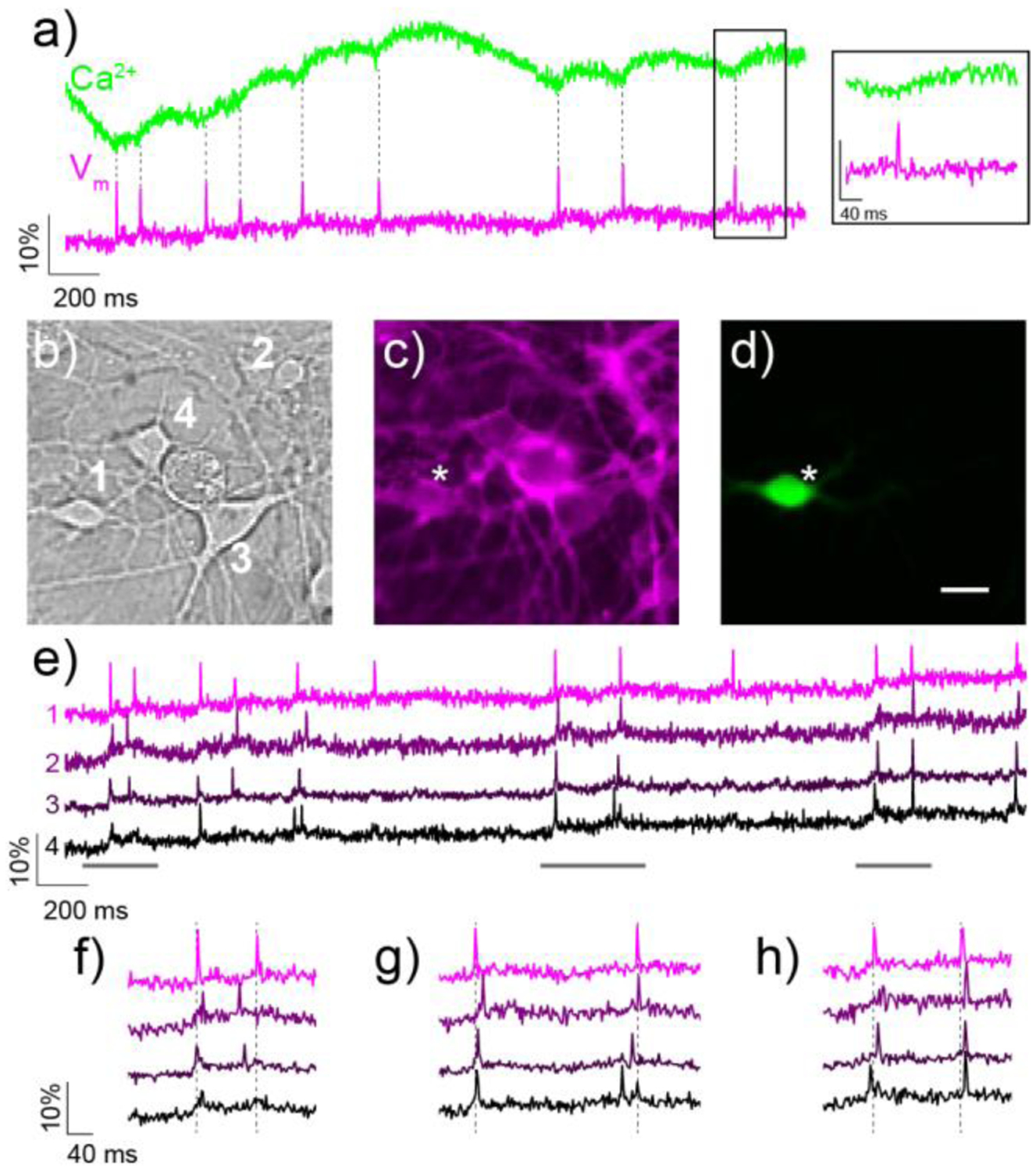

Rhodamine-based voltage reporters, or RhoVR dyes, feature a tetramethylrhodamine fluorophore and phenylenevinylene molecular wire (Figure 2). The initial RhoVR dye featured a sarcosine amide in place of the typical sulfonate, enabling greater flexibility in the selection of polar groups for retention of dyes on the external face of the cell membrane.28 RhoVR 1 shows a 47% ΔF/F per 100 mV in HEK cells and can readily detect action potentials in cultured neurons. The longer wavelength of tetramethyl rhodamine allows RhoVR 1 to be deployed alongside blue indicators like GCaMP or GFP, for multi-color imaging (Figure 4a–h). A sulfonated version of RhoVR 1, sRhoVR, possesses similar voltage sensitivity (44% ΔF/F, Figure 2).29

Figure 4.

Simultaneous two-color imaging of voltage and Ca2+ in hippocampal neurons using RhoVR 1 and GCaMP6s. a) The green trace shows the relative change in fluorescence from Ca2+-sensitive GCaMP6s, while the magenta trace depicts relative fluorescence changes in RhoVR 1 fluorescence from neuron 1 in (b). The inset shows an expand time scale of the boxed region. b) DIC image of neurons expressing GCaMP6s and stained with RhoVR 1. c) Fluorescence image showing membrane localization of RhoVR 1 fluorescence from neurons in (b). d) Fluorescence image of neurons in (b) showing GCaMP6s fluorescence. Scale bar is 20 μm. e) Traces showing the activity of each neuron in (b–d), displayed as the fractional change in voltage-sensitive RhoVR 1 fluorescence vs time. (f–h) Regions of the traces in (e) are shown on an expanded time scale to compare the spike timing of imaged neurons.

An alternative approach to accessing voltage indicators with excitation profiles in the green region of the spectrum is to use fluorescein-based indicators with carbon substitution at the bridgehead position of the xanthene.30 We devised new synthetic routes to access sulfonated carbofluoresceins and incorporated these new dyes into a molecular wire voltage sensing scaffold. The resulting carboVoltageFluor dyes (Figure 2), with either H, Cl, or F substitution patterns, are voltage sensitive and can report on action potentials in cultured neurons.31 Importantly, the use of fluorescein-like xanthene dyes, as opposed to rhodamine-type fluorophores, offers the opportunity to incorporate the red-shifted carboVF dyes into fluorogenic targeting strategies (see below).

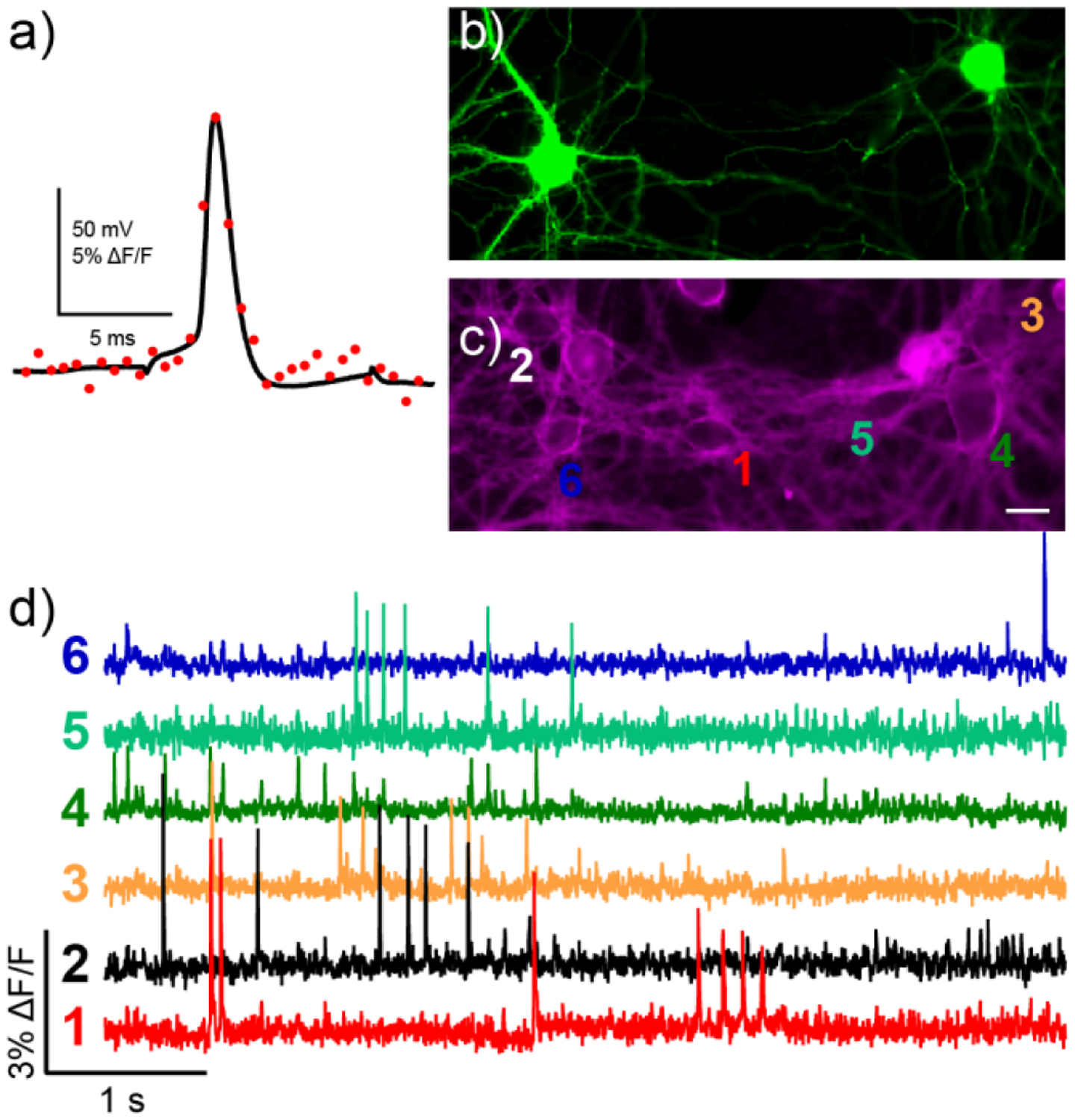

To push the excitation and emission wavelengths of voltage-sensitive fluorophores into the far-red and near-infrared regions of the spectrum, we turned to silicon-substituted rhodamines.32–33 A key challenge in the synthesis of Si-rhodamine based voltage indicators was the generation of a sulfonated tetramethyl silicon rhodamine, which we accomplished through the activation of the vinylogous urea intermediate with triflic anhydride.34 Use of methoxy-substituted phenylenevinylene provides Berkeley Red Sensor of Transmembrane potential, or BeRST 1 (Figure 2). BeRST 1 displays excellent photostability (5× compared to VF2.1.Cl), far-red to near infrared excitation and emission, and outstanding signal to noise with a 24% ΔF/F sensitivity (Figure 5).34 The large spectral separation from GFP- and fluorescein-based indicators means that BeRST 1 can be combined with optical indicators like GCaMP, or actuators like ChannelRhodopsin-2 to perform “all-optical electrophysiology,” in which blue light excitation of ChR2 depolarizes neurons and far-red excitation of BeRST 1 provides a read-out of neuronal activity.

Figure 5.

Characterization of BeRST 1 in neurons. a) Dual electrical (black trace) and optical recording (red dots, 1.8 kHz frame rate) from a hippocampal neuron stained with BeRST 1 was subjected to whole-cell current clamp and stimulated to induce action potential firing. A small stimulus artifact is apparent before and after the action potential in the black trace. (b-d) Spontaneous voltage imaging in GFP-labeled cells with BeRST 1. Epifluorescence images of rat hippocampal neurons expressing b) GFP and c) stained with BeRST 1. Scale bar is 20 μm. d) Optical traces of spontaneous activity in neurons from panels (b) and (c). Numbers next to traces correspond to indicated cells in panel (c). Optical sampling rate is 500 Hz.

2P-active dyes, including RVF5, sRhoVR, and RhoVR

The generalizable approach of VoltageFluors affords a unique opportunity to incorporate dyes with exceptional two photon (2P) performance for imaging in deep tissue. We show that the use of fluorophores like rhodols and rhodamines, with high 2P cross sections (4- to 5-fold greater than GFP),35–36 can be readily incorporated into VF-like scaffolds for voltage sensing.29, 37 The first of these indicators is Rhodol VoltageFluor, RVF5,37 which features a fluorescein-rhodamine hybrid, or rhodol, fluorophore (Figure 2). Under single photon illumination, RVF5 possesses excitation and emission maxima at 520 nm and 535 nm and a voltage sensitivity of 28% ΔF/F. Under 2P illumination, RVF5 absorbs maximally at 820 nm, with a 2P absorption cross section of 120 GM. RVF5 retains its voltage sensitivity under 2P illumination (approximately 24% ΔF/F), consistent with a voltage sensing mechanism that requires PeT during the excited state of the fluorophore. Rhodamine-based indicators like RhoVR 128 and sRhoVR29 can also sense voltage under 2P illumination (Figure 2). Importantly, both RVF5 and sRhoVR enable voltage imaging in mouse, either in brain slice or in the intact somatosensory cortex. Both of these studies provide mechanistic insight into the mode of voltage sensitivity and reveal fundamentally new biological observations that would be difficult to make without these probes.

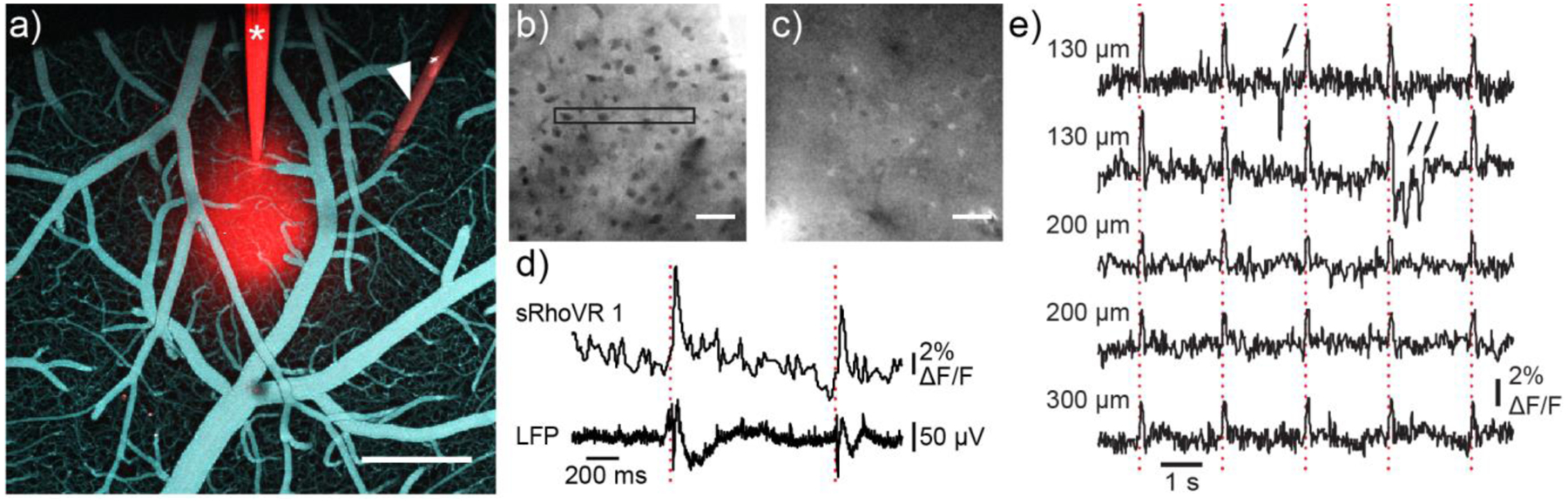

First we used RVF5 in a mouse model of the epilepsy disorder, tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Using a voltage-imaging approach, we find that cultured neurons deficient in the Tsc1 gene show increased activity compared to wild-type neurons.37 These results corroborate earlier studies38 and reveal that Tsc1 knock-out alters overall neuronal network properties by increasing the proportion of actively firing cells compared to wild-type cultures.37 Second, we used sRhoVR for two-photon, in vivo imaging within the somatosensory cortex of live mice (Figure 6). We optically recorded changes in transmembrane potential with 2P microscopy from depths of up to 300 μm below the surface of the brain.29 In response to whisker stimulation, sRhoVR reveals a transmembrane depolarization. Comparison with traditional electrode-based extracellular potential recordings allows us to establish for the first time the relationship between extracellularly recorded potentials and transmembrane potentials at different depths within the brain, linking physical structures within the brain to functional output. Additionally, this study showed the compatibility of PeT-based voltage indicators with live brain imaging in mice, while simultaneously revealing the challenge of obtaining single-cell resolution in the absence of genetic targeting (Figure 6b–c). Taking advantage of the high 2P performance of rhodamine-type dyes, RhoVR 2 (Figure 2) has been coupled to emerging highspeed 2P microscopy to provide single-trial resolution of action potentials in neurons under 2P illumination.39

Figure 6.

Two-photon voltage imaging in mouse cortex with sRhoVR. sRhoVR (100 to 200 μM in ACSF) was pressure-injected through a glass or quartz micropipette into layer 2/3 of the barrel cortex of an anesthetized mouse. a) A view from the top on the cortical surface after intracortical injection of sRhoVR (red) and intravascular injection of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated dextran (cyan); the sRhoVRfilled glass pipet (asterisk) and tungsten electrode (white arrowhead) are visible. Scale bar, 500 μm. b) Typical two-photon images of tissue staining with sRhoVR in cortical layer 2/3 in b) anesthetized or c) awake mice. Black rectangle depicts a typical region of interest (ROI) for data acquisition. d) Time-course of sRhoVR fluorescence, relative to baseline (ΔF/F), and local field potentials (LFP) traces acquired simultaneously in anesthetized mouse. Dotted red lines indicate timing of contralateral whisker pad stimulation with a single 300 μs weak electrical pulse. e) Time-courses of sRhoVR fluorescence relative to baseline (ΔF/F) in awake mouse; each traces corresponds to a different ROIs in the same animal at the indicated cortical depth. Dotted red lines indicate timing of contralateral whisker pad stimulation with a single air puff. Black arrows point to motion artifacts.

Targeting, including fluorogenic and covalent strategies

Mapping activity within neuronal circuits of the intact brain promises the ultimate link between molecular, cellular, and structural genotypes and the functional activity that give rise to sensation, perception, and complex brain behaviors. VoltageFluors possess the requisite speed and sensitivity to report on action potentials in neurons in single trials, but a current limitation is their lack of cell-specific targeting, which significantly erodes signal to noise and cellular resolution in whole-brain settings, compared to genetically encoded approaches.

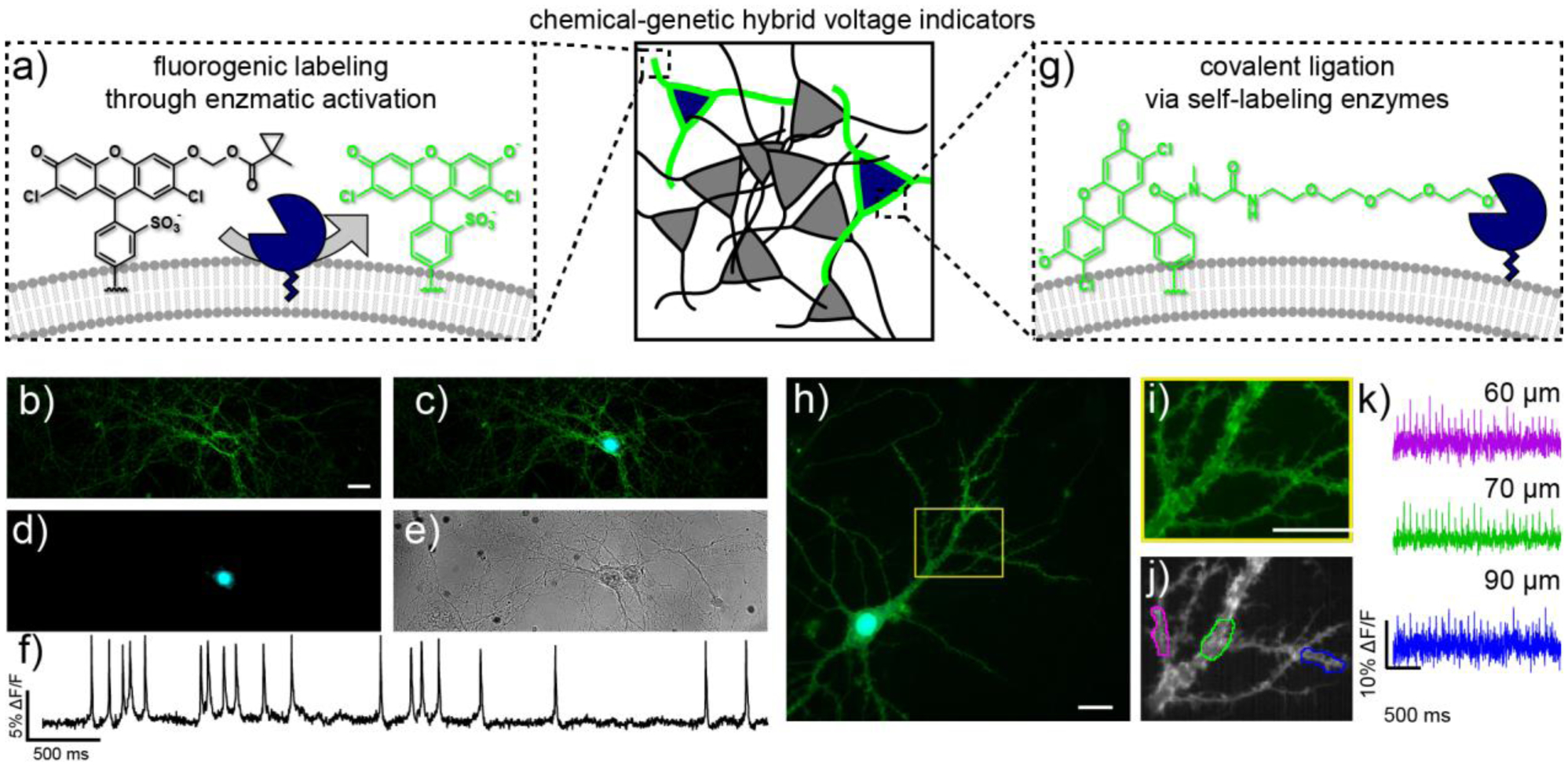

One method to address cell resolution in vivo is completely genetically encoded indicators. New classes of genetically encoded indicators have emerged in the last several years and show critical improvements in membrane trafficking and response speed. But challenges remain.10–11 Opsin-based indicators are fast and sensitive, but extremely dim and retain some ability to pass disruptive current in response to light. Opsin-fluorescent protein hybrids retain response speed and couple voltage changes to a turn-off response from a brighter fluorescent protein; more recently chemical hybrids that replace the fluorescent protein donor with small molecule fluorophores show promise.40–41 But, the complex photocycle of opsin-based reporters currently precludes 2P imaging. Fluorescent proteinbased indicators are bright, but traffic to the plasma membrane inconsistently, have relatively low 2P cross sections, and can introduce disruptive capacitive load to neurons. To marry the speed, sensitivity, and brightness of synthetic VF dyes with the cell-type specificity of genetically encoded approaches, we combine VF dyes with a genetically encoded component to enable high-contrast imaging in defined neurons, with the ultimate goal of interrogating membrane potential dynamics in the intact brains of model organisms like mice, flies, and fish. We have applied two complementary strategies to begin to address this challenge (Figure 7).

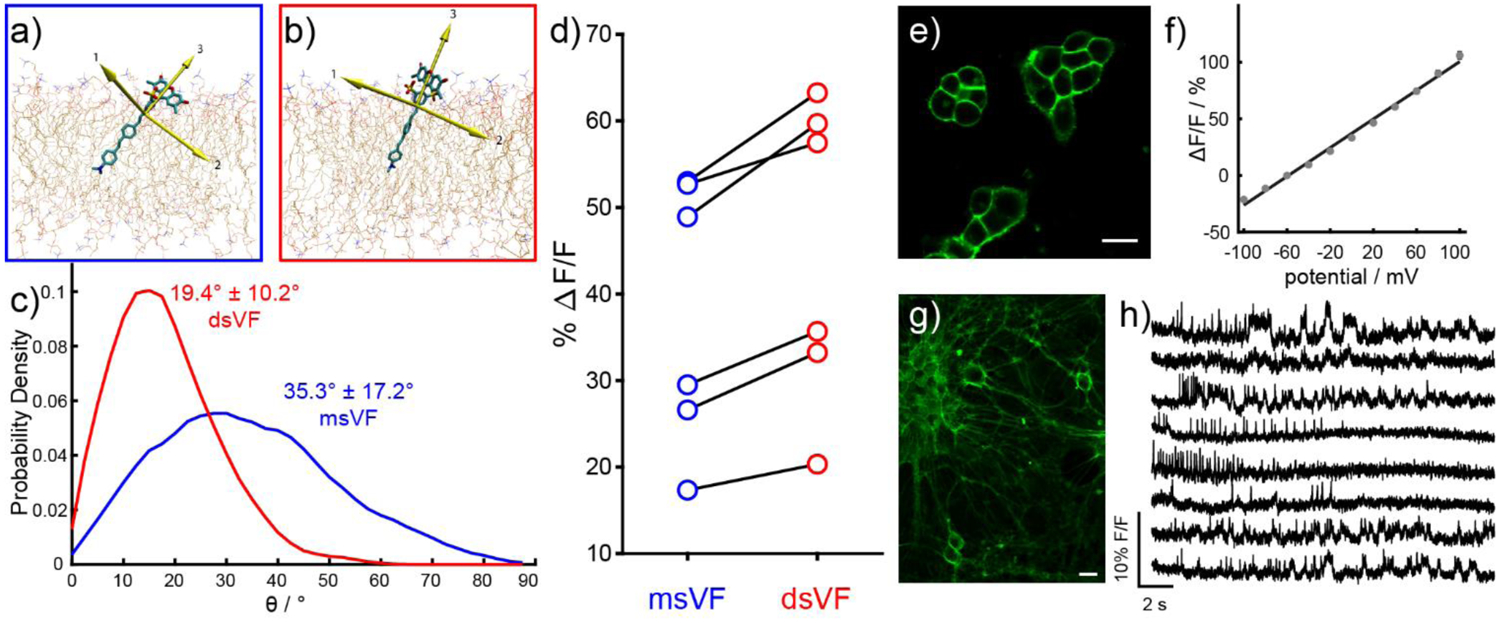

Figure 7.

Complementary strategies for genetic targeting of synthetic voltage indicators. a) Fluorogenic uncaging relies on esterase expression in defined cells. b-e) Live-cell wide-field images of rat hippocampal neurons stained with VF-EX2 expressing PLE-DAF under control of the synapsin promoter. b) Green fluorescence from VF-EX2, c) overlay of mCherry (cyan) and VF-EX2 (green) fluorescence, d) nuclearlocalized mCherry fluorescence (cyan), and e) transmitted light image of neurons. Scale bar is 20 μm. f) Representative ΔF/F traces for rat hippocampal neurons stained with VF-EX2 and transfected with Syn-PLE-DAF. Traces are ΔF/F from regions of interest at the cell bodies of neurons after background offset and are uncorrected for bleaching. Images were acquired at 500 Hz and represent single-trial acquisitions. g) Covalent targeting of VoltageFluor dyes to cell surface-expressed self-ligating enzymes. (h-k) Subcellular voltage imaging in dendrites with VoltageSpy dyes. h) Wide-field fluorescence microscopy image of a hippocampal neuron co-expressing SpyCatcher and nuclear mCherry (cyan) and labeled with VoltageSpy (green) under 63× magnification. Scale bar is 20 μm. i) Close-up of boxed region in panel (h). Scale bar is 20 μm. j) Average intensity projection of 2500 frames recorded at 500 Hz. Regions of interest (ROIs) are 10 μm long. k) ΔF/F traces of an evoked train of 25 APs. Color-coding corresponds to ROIs indicated in panel (j). Approximate distances from the center of the mCherry nucleus are indicated above each trace.

The first is a fluorogenic approach, in which the parent VF dye is chemically modified to be minimally fluorescent and must be enzymatically activated prior to imaging (Figure 7a–f). This results in bright, localized fluorescence only in the cells which express an enzyme to remove the chemical modification. Building on our initial report of targeting via photoactivation,42 we showed that bulky acetoxymethyl esters can efficiently target fluorescein-type VF dyes to specific cells.43 This hybrid VF dye, VoltageFluor targeted by esterase expression, or VF-EX, affords larger ΔF/F and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for action potentials than completely genetically encoded FP voltage sensors or FRET-opsin voltage sensors.43 This approach is generalizable: a second example of this fluorogenic approach uses red-shifted, carbofluorescein-based VF dyes (carboVFs) to achieve cell specific staining with longer wavelengths and higher voltage sensitivity.31 The ability to target specific neurons with VF dyes is another important step towards linking molecular and cellular identity with functional output: using VF-EX allowed us to demonstrate that the neuromodulatory effect of serotonin (5-HT) in hippocampal neurons is mediated by 5-HT receptor 1A, rather than other types of 5-HT receptors, like 5-HTR2.43

In a complementary fashion, we have developed covalentlytargeted voltage indicators that ligate themselves to exogenously expressed cell surface enzymes on a neuron of interest (Figure 7g–k). We co-opted the SpyTag/SpyCatcher ligand-receptor system,44 synthesizing VF dyes appended to the small SpyTag peptide, via a long, flexible polyethyleneglycol (PEG) linker.45 This strategy, VoltageSpy, results in exquisite targeting of genetically defined neurons, requiring only nanomolar quantities of dye. Covalent targeting of VF dyes enables recording of voltage dynamics from specific neurons in heterogeneous populations and from different sub-cellular compartments, like axons and dendrites (Figure 7h–k). We are now exploring voltage dynamics in sub-cellular structures, to link molecular and cellular identity to function at even high resolution – moving beyond traditional electrophysiology, which can only report on somatic voltage, and Ca2+ imaging, which cannot resolve rapidly changing membrane potential fluctuations.

Future outlook

In this Account, we describe the development and application of voltage-sensitive fluorophores that use photoinduced electron transfer as a trigger for sensing voltage changes. In the future, voltage indicators of all varieties, including chemically synthesized, genetically encoded, and hybrid indicators must address critical challenges: targeting to and retention at cellular membranes; mitigating unwanted photochemical reactions that lead to phototoxicity and dye decomposition; improving performance under multiphoton excitation; maintaining response kinetics while improving sensitivity; eliminating capacitive load or light-induced charge movement; and quantitating absolute voltage values.

Even with these outstanding challenges, we believe VoltageFluor-type dyes offer a powerful method for monitoring membrane potential across a wide range of excitation and emission wavelengths. Although our initial efforts have been centered around applications in the context of neurobiology, fast, bright, sensitive, and non-disruptive indicators will have utility across numerous areas of cell biology. Indeed, initial studies have already made use of VoltageFluor-type dyes in areas as diverse as cardiobiology,46–47 pancreatic biology,48 reproductive biology,49 and synaptic physiology.50 Future developments include expansion into near infra-red excitation and emission regions for fast imaging under one-photon conditions; engineering a suite of orthogonal enzyme/substrate and ligand/self-labeling enzyme pairs coupled to the rainbow of available VoltageFluors for multi-color voltage imaging; application of targeting strategies to in vivo model systems; allying targeted indicators with high 2P cross sections to emerging fast 2P imaging;39 and exploring the use of time-resolved microscopies to optically estimate membrane potential values.19

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

P.L. was supported by a graduate fellowship from A*STAR. Research in the Miller lab has been generously supported by the University of California, Berkeley; March of Dimes; Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; Brain Research Foundation; Klingenstein-Simons Foundations, NSF (1707350), and NIH (R35GM119855, R01NS098088).

Author Biographies

Pei Liu

Pei Liu received her B.A. in biochemistry from Mount Holyoke College in 2013. She earned her PhD in Chemistry in 2019 with Professor Evan Miller at University of California, Berkeley. Pei is currently a post-doctoral fellow with Professor Katherine Ferrara and Professor Stanley Qi at Stanford University. Her current interests focus on new methods to non-invasively control gene expression in living systems.

Evan W. Miller

Evan W. Miller is an Assistant Professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Molecular & Cell Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. Evan earned his B.S. in Chemistry/Biology and his B.A. in Philosophy/Theology from Point Loma Nazarene University in 2004. He received his PhD in Chemistry with Christopher J. Chang at UC Berkeley in 2009 before beginning post-doctoral studies with Roger Y. Tsien at UC San Diego. In 2013, Evan joined the faculty of UC Berkeley. His laboratory focuses on the development and application of fluorescent indicators to study the chemical biology of membrane potential.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This document is confidential and is proprietary to the American Chemical Society and its authors. Do not copy or disclose without written permission. If you have received this item in error, notify the sender and delete all copies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davila HV; Salzberg BM; Cohen LB; Waggoner AS, A Large Change in Axon Fluorescence that Provides a Promising Method for Measuring Membrane Potential. Nature New Biology 1973. 241, 159–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braubach O; Cohen LB; Choi Y, Historical Overview and General Methods of Membrane Potential Imaging In Membrane Potential Imaging in the Nervous System and Heart, Canepari M; Zecevic D; Bernus O, Eds. Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; pp 3–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterka DS; Takahashi H; Yuste R, Imaging Voltage in Neurons. Neuron 2011. 69, 9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller EW, Small molecule fluorescent voltage indicators for studying membrane potential. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2016. 33, 74–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montana V; Farkas DL; Loew LM, Dual-wavelength ratiometric fluorescence measurements of membrane potential. Biochemistry 1989. 28, 4536–4539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuhn B; Fromherz P, Anellated Hemicyanine Dyes in a Neuron Membrane: Molecular Stark Effect and Optical Voltage Recording. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2003. 107, 7903–7913. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klymchenko AS; Stoeckel H; Takeda K; Mély Y, Fluorescent Probe Based on Intramolecular Proton Transfer for Fast Ratiometric Measurement of Cellular Transmembrane Potential. The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2006. 110, 13624–13632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González JE; Tsien RY, Improved indicators of cell membrane potential that use fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Chemistry & Biology 1997. 4, 269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni RU; Miller EW, Voltage Imaging: Pitfalls and Potential. Biochemistry 2017. 56, 5171–5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin MZ; Schnitzer MJ, Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nature Neuroscience 2016. 19, 1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St-Pierre F; Chavarha M; Lin MZ, Designs and sensing mechanisms of genetically encoded fluorescent voltage indicators. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2015. 27, 31–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bando Y; Grimm C; Cornejo VH; Yuste R, Genetic voltage indicators. BMC Biology 2019. 17, 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bando Y; Sakamoto M; Kim S; Ayzenshtat I; Yuste R, Comparative Evaluation of Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators. Cell Reports 2019. 26, 802–813.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Silva AP; Gunaratne HQN; Habib-Jiwan J-L; McCoy CP; Rice TE; Soumillion J-P, New Fluorescent Model Compounds for the Study of Photoinduced Electron Transfer: The Influence of a Molecular Electric Field in the Excited State. Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English 1995. 34, 1728–1731. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L. s., Fluorescence Probes for Membrane Potentials Based on Mesoscopic Electron Transfer. Nano Letters 2007. 7, 2981–2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller EW; Lin JY; Frady EP; Steinbach PA; Kristan WB; Tsien RY, Optically monitoring voltage in neurons by photo-induced electron transfer through molecular wires. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012. 109, 2114–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodford CR; Frady EP; Smith RS; Morey B; Canzi G; Palida SF; Araneda RC; Kristan WB; Kubiak CP; Miller EW; Tsien RY, Improved PeT Molecules for Optically Sensing Voltage in Neurons. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2015. 137, 1817–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beier HT; Roth CC; Bixler JN; Sedelnikova AV; Ibey BL, Visualization of Dynamic Sub-microsecond Changes in Membrane Potential. Biophysical Journal 2019. 116, 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazzari-Dean JR; Gest AMM; Miller EW, Optical estimation of absolute membrane potential using fluorescence lifetime imaging. eLife 2019. 8, e44522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frady EP; Kapoor A; Horvitz E Jr., K. WB, Scalable Semisupervised Functional Neurocartography Reveals Canonical Neurons in Behavioral Networks. Neural Computation 2016. 28, 1453–1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomina Y; Wagenaar DA, A double-sided microscope to realize whole-ganglion imaging of membrane potential in the medicinal leech. eLife 2017. 6, e29839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franke JM; Raliski BK; Boggess SC; Natesan DV; Koretsky ET; Zhang P; Kulkarni RU; Deal PE; Miller EW, BODIPY Fluorophores for Membrane Potential Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019. 141, 12824–12831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boggess SC; Gandhi SS; Siemons BA; Huebsch N; Healy KE; Miller EW, New Molecular Scaffolds for Fluorescent Voltage Indicators. ACS Chemical Biology 2019. 14, 390–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulkarni RU; Yin H; Pourmandi N; James F; Adil MM; Schaffer DV; Wang Y; Miller EW, A Rationally Designed, General Strategy for Membrane Orientation of Photoinduced Electron Transfer-Based Voltage-Sensitive Dyes. ACS Chemical Biology 2017. 12, 407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adil MM; Gaj T; Rao AT; Kulkarni RU; Fuentes CM; Ramadoss GN; Ekman FK; Miller EW; Schaffer DV, hPSC-Derived Striatal Cells Generated Using a Scalable 3D Hydrogel Promote Recovery in a Huntington Disease Mouse Model. Stem Cell Reports 2018. 10, 1481–1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adil MM; Vazin T; Ananthanarayanan B; Rodrigues GMC; Rao AT; Kulkarni RU; Miller EW; Kumar S; Schaffer DV, Engineered hydrogels increase the post-transplantation survival of encapsulated hESC-derived midbrain dopaminergic neurons. Biomaterials 2017. 136, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodrigues GMC; Gaj T; Adil MM; Wahba J; Rao AT; Lorbeer FK; Kulkarni RU; Diogo MM; Cabral JMS; Miller EW; Hockemeyer D; Schaffer DV, Defined and Scalable Differentiation of Human Oligodendrocyte Precursors from Pluripotent Stem Cells in a 3D Culture System. Stem Cell Reports 2017. 8, 1770–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deal PE; Kulkarni RU; Al-Abdullatif SH; Miller EW, Isomerically Pure Tetramethylrhodamine Voltage Reporters. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016. 138, 9085–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulkarni RU; Vandenberghe M; Thunemann M; James F; Andreassen OA; Djurovic S; Devor A; Miller EW, In Vivo Two-Photon Voltage Imaging with Sulfonated Rhodamine Dyes. ACS Central Science 2018. 4, 1371–1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimm JB; Sung AJ; Legant WR; Hulamm P; Matlosz SM; Betzig E; Lavis LD, Carbofluoresceins and Carborhodamines as Scaffolds for High-Contrast Fluorogenic Probes. ACS Chemical Biology 2013. 8, 1303–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ortiz G; Liu P; Naing SHH; Muller VR; Miller EW, Synthesis of Sulfonated Carbofluoresceins for Voltage Imaging. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019. 141, 6631–6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fu M; Xiao Y; Qian X; Zhao D; Xu Y, A design concept of long-wavelength fluorescent analogs of rhodamine dyes: replacement of oxygen with silicon atom. Chemical Communications 2008. 1780–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koide Y; Urano Y; Hanaoka K; Terai T; Nagano T, Evolution of Group 14 Rhodamines as Platforms for Near-Infrared Fluorescence Probes Utilizing Photoinduced Electron Transfer. ACS Chemical Biology 2011. 6, 600–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang Y-L; Walker AS; Miller EW, A Photostable Silicon Rhodamine Platform for Optical Voltage Sensing. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2015. 137, 10767–10776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drobizhev M; Makarov NS; Tillo SE; Hughes TE; Rebane A, Two-photon absorption properties of fluorescent proteins. Nature Methods 2011. 8, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu C; Webb WW, Measurement of two-photon excitation cross sections of molecular fluorophores with data from 690 to 1050 nm. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1996. 13, 481–491. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kulkarni RU; Kramer DJ; Pourmandi N; Karbasi K; Bateup HS; Miller EW, Voltage-sensitive rhodol with enhanced two-photon brightness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017. 114, 2813–2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bateup Helen S.; Johnson Caroline A.; Denefrio Cassandra L.; Saulnier Jessica L.; Kornacker K; Sabatini Bernardo L., Excitatory/Inhibitory Synaptic Imbalance Leads to Hippocampal Hyperexcitability in Mouse Models of Tuberous Sclerosis. Neuron 2013. 78, 510–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kazemipour A; Novak O; Flickinger D; Marvin JS; Abdelfattah AS; King J; Borden PM; Kim JJ; Al-Abdullatif SH; Deal PE; Miller EW; Schreiter ER; Druckmann S; Svoboda K; Looger LL; Podgorski K, Kilohertz frame-rate two-photon tomography. Nature Methods 2019. 16, 778–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Y; Peng L; Wang S; Wang A; Ma R; Zhou Y; Yang J; Sun D.-e.; Lin W; Chen X; Zou P, Hybrid Indicators for Fast and Sensitive Voltage Imaging. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2018. 57, 3949–3953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdelfattah AS; Kawashima T; Singh A; Novak O; Liu H; Shuai Y; Huang Y-C; Campagnola L; Seeman SC; Yu J; Zheng J; Grimm JB; Patel R; Friedrich J; Mensh BD; Paninski L; Macklin JJ; Murphy GJ; Podgorski K; Lin B-J; Chen T-W; Turner GC; Liu Z; Koyama M; Svoboda K; Ahrens MB; Lavis LD; Schreiter ER, Bright and photostable chemigenetic indicators for extended in vivo voltage imaging. Science 2019. 365, 699–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grenier V; Walker AS; Miller EW, A Small-Molecule Photoactivatable Optical Sensor of Transmembrane Potential. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2015. 137, 10894–10897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu P; Grenier V; Hong W; Muller VR; Miller EW, Fluorogenic Targeting of Voltage-Sensitive Dyes to Neurons. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017. 139, 17334–17340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zakeri B; Fierer JO; Celik E; Chittock EC; SchwarzLinek U; Moy VT; Howarth M, Peptide tag forming a rapid covalent bond to a protein, through engineering a bacterial adhesin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012. 109, E690–E697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grenier V; Daws BR; Liu P; Miller EW, Spying on Neuronal Membrane Potential with Genetically Targetable Voltage Indicators. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2019. 141, 1349–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Streit J; Kleinlogel S, Dynamic all-optical drug screening on cardiac voltage-gated ion channels. Scientific Reports 2018. 8, 1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cunningham TJ; Yu MS; McKeithan WL; Spiering S; Carrette F; Huang CT; Bushway PJ; Tierney M; Albini S; Giacca M; Mano M; Puri PL; Sacco A; Ruiz-Lozano P; Riou JF; Umbhauer M; Duester G; Mercola M; Colas AR, Id genes are essential for early heart formation. Genes & development 2017. 31, 1325–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scattolini V; Luni C; Zambon A; Galvanin S; Gagliano O; Ciubotaru CD; Avogaro A; Mammano F; Elvassore N; Fadini GP, Simvastatin Rapidly and Reversibly Inhibits Insulin Secretion in Intact Single-Islet Cultures. Diabetes Therapy 2016. 7, 679–693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hamzeh H; Alvarez L; Strünker T; Kierzek M; Brenker C; Deal PE; Miller EW; Seifert R; Kaupp UB, Chapter 22 - Kinetic and photonic techniques to study chemotactic signaling in sea urchin sperm In Methods in Cell Biology, Hamdoun A; Foltz KR, Eds. Academic Press: 2019; Vol. 151, pp 487–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Farsi Z; Preobraschenski J; van den Bogaart G; Riedel D; Jahn R; Woehler A, Single-vesicle imaging reveals different transport mechanisms between glutamatergic and GABAergic vesicles. Science 2016. 351, 981–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]