INTRODUCTION

Despite tremendous advances in medicine, adverse pregnancy outcomes continue to be major public health concerns. Approximately 8% of live births are LBW (defined as birth weight less than 2500 g), and approximately 10% are PTB (defined as birth before 37 completed weeks of gestation [World Health Organization et al. 2012]) in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1999, 2002). LBW has been associated with increased risks of chronic diseases in later life such as metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases (Chernausek 2012), as well as wheezing and asthma in childhood (Caudri et al. 2007). PTB, a major cause of infant death and morbidity, has been associated with various long-term effects, including impaired vision, hearing, and cognitive function; decreased motor function; and behavioral disorders (Saigal and Doyle 2008).

Other complications are also prevalent in pregnant women. Preeclampsia is a hypertensive syndrome specific to pregnancy, defined as new hypertension (diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mm Hg) and substantial proteinuria (≥ 300 mg in 24 h) at or after 20 weeks’ gestation (Steegers et al. 2010). Preeclampsia and eclampsia affect 2% to 8% of pregnancies worldwide and are major causes of maternal diseases, disability, and death (World Health Organization 2011). GDM, defined as an intolerance to glucose that is first diagnosed or has its onset during pregnancy, occurs in 1% to 14% of pregnancies, depending on race/ethnicity and diagnostic criteria (Ferrara 2007). This complication has serious consequences for both infant and mother, for example, a predisposition to obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes later in life (Fetita et al. 2006).

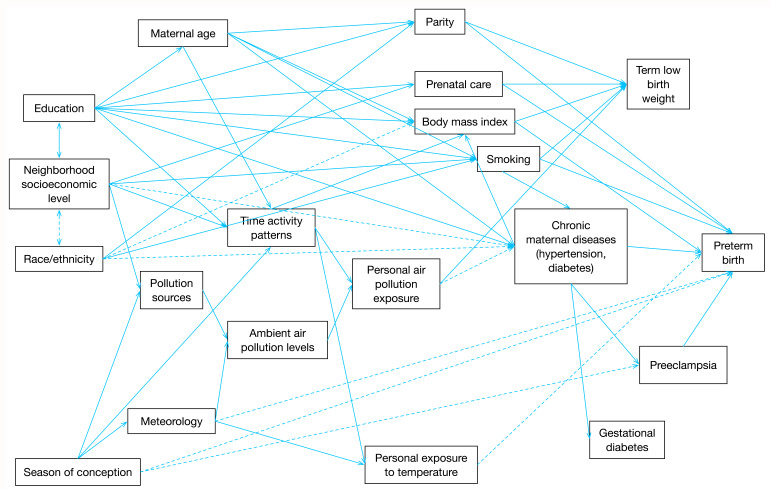

A growing body of literature has examined the impact of air pollution exposure on pregnancy outcomes because of the susceptibility of the growing fetus to the toxic effects of pollutants. Earlier review papers suggested that air pollution had effects on fetal development, but the evidence was difficult to synthesize because of heterogeneity in study designs, methods, available data, and exposure assessment methods (Glinianaia et al. 2004; Lacasana et al. 2005; Maisonet et al. 2004; Srám et al. 2005; Stillerman et al. 2008; Woodruff et al. 2009). Despite the remarkable variability of the reported results according to study settings and methodologies, two later meta-analyses on LBW and PTB found a statistically significantly positive association between air pollution and the adverse outcomes (Dadvand et al. 2013b; Stieb et al. 2012). But the existing evidence does not clearly identify the individual pollutants, multi-pollutant mixtures, or pollution sources that pose the greatest risk. This specific information is critical in formulating environmental policy that adequately protects vulnerable populations. Research on the impact of air pollution on pregnancy outcomes faces several serious gaps:

Few studies consider spatial and temporal parameters of multiple pollutants, particularly species in PM of different sizes, and most studies lack source information on PM.

Few studies address the impact of air pollution on the development of pregnancy complications.

No study has examined how both maternal obesity and gestational weight gain modify the effect of pollutants.

PM varies in composition (e.g., in the amount of elemental carbon, nitrates, transition metals [such as zinc, iron, and nickel], PAHs, and other organic compounds). Some of those components of PM can cause oxidative stress and inflammation (Delfino et al. 2010; Schlesinger et al. 2006). The composition of PM varies greatly between seasons and geographical settings and has therefore been hypothesized to modify the relationship between total PM mass and pregnancy outcomes (Bell et al. 2007). In addition, PM0.1 (particulates with aerodynamic diameter ≤ 0.1 μm, known as ultrafine particles [UFPs]) have high pulmonary deposition efficiency and large surface areas that can adsorb large amounts of toxic air pollutants (Li et al. 2003). For this reason, UFPs are probably the size fraction with the most redox-active components and the greatest capacity to induce oxidative stress and inflammatory responses (Araujo et al. 2008; Jeng 2010; Li et al. 2003; Ntziachristos et al. 2007; Xia et al. 2004). However, so far, only a few studies have investigated the associations of PM species and UFPs with LBW (Basu et al. 2014; Bell et al. 2010, 2012; Darrow et al. 2011; Ebisu and Bell 2012) and PTB (Darrow et al. 2009; Wilhelm et al. 2011), probably because of the scarcity of data on particle size distribution and speciation data.

There are also open questions, of direct relevance to policy, on the sources of air pollution most likely to cause the adverse pregnancy outcomes. Several recent publications, including our previous work, have suggested a possible influence of primary emissions from vehicular traffic on pregnancy outcomes (Ritz and Wilhelm 2008; Wu et al. 2009b). The influence of other sources of air pollution (e.g., wood burning and meat cooking, both of which notably generate PAHs and other organic compounds) has also been suggested (Boy et al. 2002; Wilhelm et al. 2012). However, only a few studies assessed simultaneously the relative contributions of different sources of air pollution to the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes (Bell et al. 2010; Dadvand et al. 2014a; Wilhelm et al. 2011).

Further, the impact of air pollution exposure on the development of pregnancy complications has rarely been studied previously. Air pollution exposure might cause pregnancy complications, which in turn might cause adverse birth outcomes. A few studies, including our own, have examined the risk of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension from ambient air pollution exposures, and the reported results were mixed (see Dadvand et al. 2014a; Lee et al. 2013; Malmqvist et al. 2013; Olsson et al. 2013; Pedersen et al. 2014; Pereira et al. 2013; Rudra et al. 2011; van den Hooven et al. 2009; Vinikoor-Imler et al. 2012; Wu et al. 2009b; Xu et al. 2014). However, a recent meta-analysis showed a statistically significant positive association between ambient air pollution exposure and the risk of preeclampsia (Pedersen et al. 2014). There are even fewer studies on ambient air pollution and GDM (Ferrara 2007; Malmqvist et al. 2013; Pereira et al. 2013; van den Hooven et al. 2009) than there are for preeclampsia. Clearly, more research is needed to elucidate the possible effects of air pollution on the development of pregnancy complications.

Moreover, the increasing prevalence of being overweight and obesity among women of childbearing age is a growing public health concern in the United States (Siega-Riz et al. 2006). Obesity correlates with sociodemographic factors (Chu et al. 2009). Two review papers have documented clear associations of maternal obesity with fetal risks (e.g., miscarriage, PTB, birth defects) and maternal risks (e.g., preeclampsia, GDM) (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2006; Ramachenderan et al. 2008). In addition to obesity, maternal gestational weight gain may be an independent risk factor for adverse reproductive outcomes (Chen et al. 2009; Kiel et al. 2007; Nohr et al. 2009). However, little is known about the effect modification by both maternal obesity and gestational weight gain on the risk of air pollution on reproductive outcomes.

RESULTS

In this report, we consider the mean exposures during the entire pregnancy as the exposure of primary interest. Results for specific exposure periods are summarized in this section, but detailed data for each adverse pregnancy outcome are presented in the appendices. We present summary statistics for the distribution of air pollution exposures during the entire pregnancy (Appendix A, Table A.3) and the long-term trends of exposures by year of birth during the study period (Appendix A, Table A.4). The correlation matrix for exposures to major air pollutants is shown in Appendix A, Table A.5 (traffic index and UCD_P modeled concentrations were omitted in this table because of space limitations). The distributions of the mean air pollutants exposures by the categories of potential effect modifiers (e.g., maternal age, education, race/ethnicity, household income) are summarized in Appendix A, Tables A.6 through A.13.

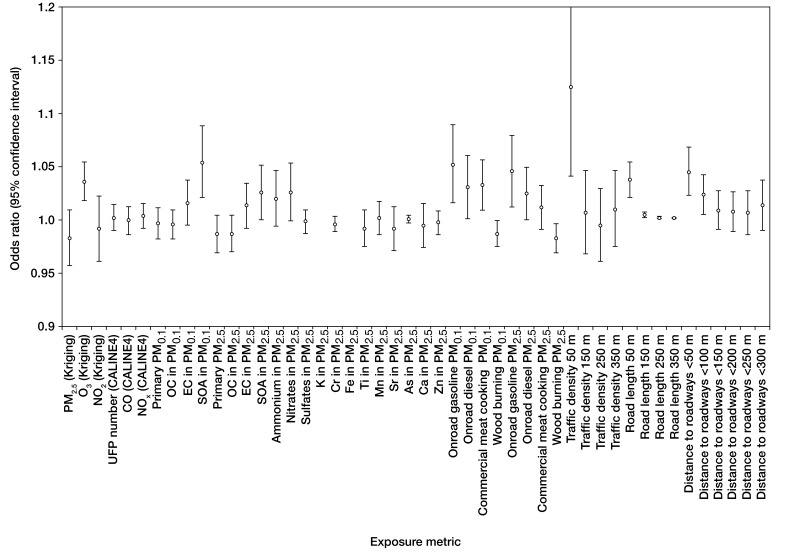

TERM LOW BIRTH WEIGHT

When exposure averaged over the entire pregnancy was considered, term LBW was positively associated with EBK-interpolated measurements of O3 (OR per IQR in exposure: 1.035; 95% CI: 1.017–1.054) but not of total PM2.5 or NO2 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Associations between term low birth weight and air pollution in California, 2001–2008a

| Air pollution indicator |

Cases |

IQRb

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)c

|

P value |

| Measured pollutant concentrations interpolated by empirical Bayesian kriging (EBK) |

| PM2.5 |

68,887 |

6.47 |

0.982 (0.956; 1.009) |

0.20 |

| O3 |

68,952 |

10.80 |

1.035 (1.017; 1.054) |

<0.01 |

| NO2 |

68,574 |

10.25 |

0.991 (0.960; 1.022) |

0.56 |

|

UCD/CIT modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and species

|

| Primary PM0.1

|

65,391 |

1.359 |

0.996 (0.981; 1.011) |

0.58 |

| OC in PM0.1

|

65,391 |

0.958 |

0.995 (0.981; 1.009) |

0.49 |

| EC in PM0.1

|

65,391 |

0.131 |

1.015 (0.994; 1.037) |

0.16 |

| SOA in PM0.1

|

65,391 |

0.060 |

1.053 (1.020; 1.088) |

<0.01 |

| Primary PM2.5

|

65,391 |

8.225 |

0.986 (0.968; 1.004) |

0.13 |

| OC in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

3.630 |

0.986 (0.969; 1.004) |

0.12 |

| EC in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

1.265 |

1.013 (0.991; 1.034) |

0.24 |

| SOA in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

0.228 |

1.025 (0.999; 1.051) |

0.06 |

| Ammonium in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

1.189 |

1.019 (0.993; 1.046) |

0.16 |

| Nitrates in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

2.916 |

1.025 (0.998; 1.053) |

0.07 |

| Sulfates in PM2.5

|

65,391 |

0.535 |

0.998 (0.986; 1.009) |

0.69 |

| UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by species, in PM2.5 |

| K in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.053 |

No convergence |

NA |

| Cr in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.002 |

0.995 (0.988; 1.003) |

0.20 |

| Fe in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.191 |

No convergence |

NA |

| Ti in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.008 |

0.991 (0.974; 1.009) |

0.34 |

| Mn in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.004 |

1.001 (0.985; 1.017) |

0.91 |

| Sr in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.001 |

0.991 (0.970; 1.012) |

0.38 |

| As in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.001 |

1.000 (0.996; 1.004) |

0.97 |

| Ca in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.048 |

0.994 (0.973; 1.015) |

0.56 |

| Zn in PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.002 |

0.997 (0.985; 1.008) |

0.58 |

|

UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and source

|

| Onroad gasoline PM0.1

|

48,541 |

0.083 |

1.051 (1.015; 1.089) |

0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM0.1

|

48,541 |

0.070 |

1.030 (1.000; 1.060) |

0.05 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM0.1

|

48,541 |

0.124 |

1.032 (1.008; 1.056) |

0.01 |

| Wood burning PM0.1

|

48,541 |

0.260 |

0.986 (0.974; 0.999) |

0.03 |

| Onroad gasoline PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.385 |

1.045 (1.011; 1.079) |

0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM2.5

|

48,541 |

0.397 |

1.024 (0.999; 1.049) |

0.06 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM2.5

|

48,541 |

1.094 |

1.011 (0.990; 1.032) |

0.32 |

| Wood burning PM2.5

|

48,541 |

1.736 |

0.982 (0.968; 0.996) |

0.01 |

|

Spatial (PAH) or spatiotemporal (NO2)regression models (in Los Angeles County only)

|

| PAH |

21,921 |

6.54 |

0.995 (0.971; 1.02) |

0.69 |

| NO2

|

21,921 |

|

No convergence |

|

| CALINE4 modeled concentrations |

| UFP number |

66,120 |

6444 |

1.001 (0.989; 1.014) |

0.85 |

| CO |

66,120 |

60.63 |

0.999 (0.985; 1.012) |

0.83 |

| NOx

|

66,120 |

6.10 |

1.003 (0.991; 1.015) |

0.62 |

| Traffic density (odds ratios per 10,000 vehicles per day per meter, within buffers of different sizes) |

| 50 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.124 (1.040; 1.214) |

≤0.01 |

| 150 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.006 (0.967; 1.046) |

0.77 |

| 250 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

0.994 (0.960; 1.029) |

0.73 |

| 350 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.009 (0.974; 1.046) |

0.61 |

|

Road length (odds ratios per 100 m of road length, within buffers of different sizes)

|

| 50 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.037 (1.020; 1.054) |

≤0.01 |

| 150 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.004 (1.001; 1.007) |

0.02 |

| 250 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.001 (1.000; 1.003) |

0.08 |

| 350 m buffer |

69,575 |

|

1.001 (1.000; 1.002) |

0.05 |

| Distance to roadways |

| Less than 50 m |

70,003 |

|

1.044 (1.022; 1.068) |

≤0.01 |

| Less than 100 m |

70,003 |

|

1.023 (1.004; 1.042) |

0.02 |

| Less than 150 m |

70,003 |

|

1.008 (0.990; 1.027) |

0.37 |

| Less than 200 m |

70,003 |

|

1.007 (0.988; 1.026) |

0.47 |

| Less than 250 m |

70,003 |

|

1.006 (0.985; 1.027) |

0.58 |

| Less than 300 m |

70,003 |

|

1.013 (0.989; 1.037) |

0.29 |

No significant association was observed between term LBW and primary PM2.5 or PM0.1 from all sources grouped together, modeled at a 4 km × 4 km resolution. However, term LBW risk was positively associated with primary PM2.5 and PM0.1 emitted by onroad gasoline vehicles (OR per IQR in exposure for PM0.1: 1.051; 95% CI: 1.015–1.089), onroad diesel vehicles (OR per IQR in exposure for PM0.1: 1.030; 95% CI: 1.000–1.060), and commercial meat cooking (in PM0.1 only). Associations were slightly weaker for the PM2.5 than for the PM0.1 fraction but still statistically significant for onroad gasoline and diesel vehicles. Conversely, primary PM from wood burning (both in the PM0.1 and the PM2.5 fractions) was inversely associated with term LBW risk. Still, at the 4 km × 4 km modeling resolution, a significant positive association was observed for only one chemical component, namely, for SOA in PM0.1. However, positive associations were close to significance for SOA and nitrates in PM2.5.

No significant association was observed between term LBW and PAH (modeled by the spatial model in Los Angeles County only). Convergence was not reached for NO2.

When we modeled primary emissions from local traffic at a fine geographical resolution using CALINE4, we found no association between term LBW and UFP number, CO, or NOx in the entire population (Table 5). However, when analyses were restricted to the population in which maternal addresses could be geocoded most accurately (i.e., at the exact parcel centroid), all three pollutants were positively associated with term LBW (Appendix B [available on the HEI Web site], Table B.1). The association was significant for UFP number (OR per IQR in exposure: 1.031; 95% CI: 1.006–1.056) and close to significance for NOx (OR per IQR in exposure: 1.024; 95% CI: 0.999–1.050).

When simpler indicators of traffic exposure were considered, term LBW was significantly associated with road traffic indicators within 50 m from maternal homes: traffic density (OR per 10,000 vehicles per day per meter: 1.124; 95% CI: 1.040–1.214) and total road length (OR per 100 m of cumulated road length within the buffer: 1.037; 95% CI: 1.020–1.054).

In addition, term LBW risk was significantly increased in women living within 50 m (OR: 1.044; 95% CI: 1.022– 1.068) and 100 m (OR: 1.023; 95% CI: 1.004–1.042) of a roadway. Odds ratios regularly decreased from 50 m to 250 m, although none was statistically significant beyond 100 m (Table 5).

We explored the association between term LBW and exposure to air pollution during different trimesters of pregnancy for the air pollution indicators measured and modeled with sufficient temporal resolution (e.g., not the road traffic indicators or the Los Angeles–specific NO2 and PAH models). Associations between either measured or modeled pollutant concentrations appear to be consistently stronger for exposure occurring during the third trimester of pregnancy than during the first two, except for O3 and SOA (the association being strongest for the second trimester of pregnancy) (Appendix B, Table B.2). Term LBW was positively associated with exposure to EC, ammonium, and nitrates averaged on the third trimester of pregnancy, but not during other temporal windows of exposure.

When associations between term LBW and exposure averaged on the entire pregnancy were examined in specific subgroups, overall associations with primary emissions appeared stronger in the group with the lowest education level (less than 8th grade), although significant heterogeneity of risk across education subgroups was observed only for EC in PM2.5, onroad gasoline, and meat cooking, and the number of cases in the group with the lowest education level was small (Appendix B, Table B.3). However, when indices of traffic density, road length, or residential distance to roadways were considered, associations were higher in the group with some college education. This interaction was statistically significant in the 50 m and 150 m buffers.

When the population was stratified according to quartiles of median income at the census block-group level, the highest associations were generally observed in either the first or the fourth quartiles of median income (Appendix B, Table B.4). This pattern was consistent across most exposure indicators. However, heterogeneity tests could not be conducted for many air pollutants, because of convergence problems in many subgroups.

The comparison of the magnitude of associations across race/ethnicities was even more difficult for ambient pollutant concentrations because very few models converged in the smallest subgroup of African American mothers (Appendix B, Table B.5). More models converged for traffic density, road length, and residential distance to roadways. No significant heterogeneity of risk across race/ethnicity subgroups was observed for any air pollution indicator.

Associations between air pollutant concentrations (either measured or modeled) were generally higher in mothers with chronic hypertension than without this condition, although interactions were significant only for NO2 and ammonium and close to significant for O3 (Appendix B, Table B.6). Odds ratios were generally slightly higher in mothers with diabetes than without it (Appendix B Table, B.7), but no significant heterogeneity of associations was detected for this condition. Again, many models did not converge.

We observed no significant heterogeneity of associations or consistent pattern for BMI at the beginning of pregnancy (Appendix B, Table B.8) or for weight gain during pregnancy (Appendix B, Table B.9). Lower associations between pollutant concentrations and term LBW were generally reported in mothers who declared smoking at some point during pregnancy than in mothers who did not (Appendix B, Table B.10). This was significant for total PM2 5, UFP from traffic sources modeled with CALINE4, and distance to roadways (the ≤ 300 m category). However, because the number of mothers who declared that they smoked was very small, the estimates in this subgroup were unstable.

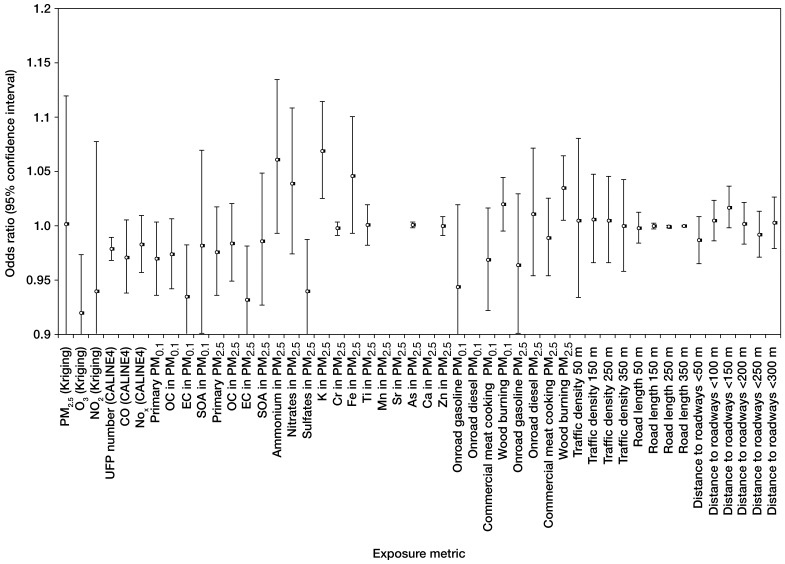

PRETERM BIRTHS

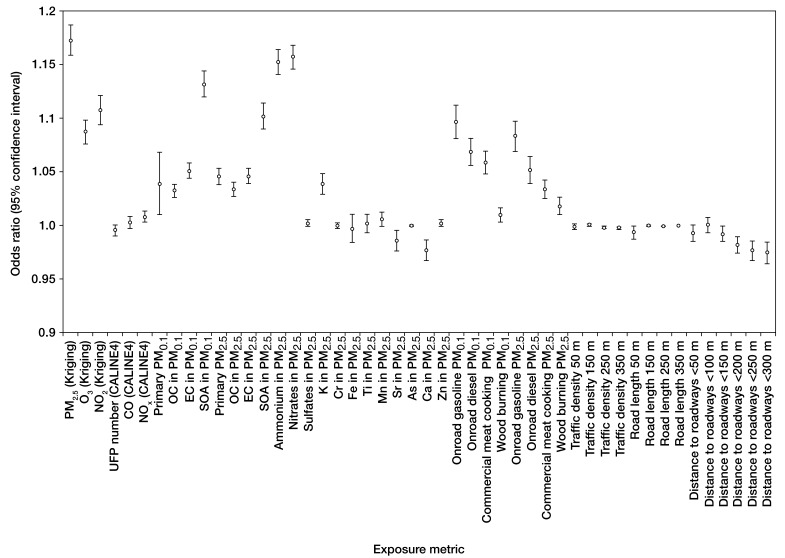

For exposure averaged on the entire pregnancy, PTB risk was positively associated with EBK-interpolated measurements of total PM2.5, O3, and NO2 (Table 6). The largest association was observed for total PM2.5 (interquartile OR: 1.172; 95% CI: 1.158–1.187).

Table 6.

Associations between preterm births and air pollution in California, 2001–2008

| Air pollution indicator |

Cases |

IQRb

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)c

|

P value |

| Measured pollutant concentrations interpolated by empirical Bayesian kriging (EBK) |

| PM2.5

|

377,631 |

6.51 |

1.172 (1.158; 1.187) |

<0.01 |

| O3

|

379,274 |

11.69 |

1.087 (1.075; 1.098) |

<0.01 |

| NO2

|

376,995 |

10.11 |

1.107 (1.093; 1.121) |

<0.01 |

|

UCD/CIT modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and species

|

| Primary PM0.1

|

356,078 |

1.389 |

1.038 (1.009; 1.068) |

<0.01 |

| OC in PM0.1

|

356,078 |

0.984 |

1.032 (1.025; 1.038) |

<0.01 |

| EC in PM0.1

|

356,078 |

0.131 |

1.050 (1.043; 1.058) |

<0.01 |

| SOA in PM0.1

|

356,078 |

0.061 |

1.131 (1.119; 1.144) |

<0.01 |

| Primary PM2.5

|

356,078 |

8.358 |

1.045 (1.037; 1.053) |

<0.01 |

| OC in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

3.718 |

1.033 (1.026; 1.040) |

<0.01 |

| EC in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

1.260 |

1.045 (1.038; 1.053) |

<0.01 |

| SOA in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

0.243 |

1.101 (1.089; 1.114) |

<0.01 |

| Ammonium in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

1.194 |

1.152 (1.140; 1.164) |

<0.01 |

| Nitrates in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

2.900 |

1.157 (1.145; 1.168) |

<0.01 |

| Sulfates in PM2.5

|

356,078 |

0.502 |

1.001 (0.998; 1.005) |

0.52 |

| UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by species, in PM2.5 |

| K in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.053 |

1.038 (1.028; 1.048) |

<0.01 |

| Cr in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.002 |

0.999 (0.996; 1.002) |

0.46 |

| Fe in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.191 |

0.996 (0.983; 1.010) |

0.58 |

| Ti in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.008 |

1.001 (0.992; 1.010) |

0.79 |

| Mn in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.004 |

1.005 (0.998; 1.012) |

0.18 |

| Sr in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.001 |

0.985 (0.975; 0.995) |

<0.01 |

| As in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.001 |

0.999 (0.998; 1.000) |

0.14 |

| Ca in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.048 |

0.976 (0.966; 0.986) |

<0.01 |

| Zn in PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.002 |

1.001 (0.998; 1.005) |

0.39 |

|

UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and source

|

| Onroad gasoline PM0.1

|

261,653 |

0.083 |

1.096 (1.080; 1.112) |

<0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM0.1

|

261,653 |

0.070 |

1.068 (1.055; 1.081) |

<0.01 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM0.1

|

261,653 |

0.124 |

1.058 (1.047; 1.069) |

<0.01 |

| Wood burning PM0.1

|

261,653 |

0.269 |

1.009 (1.002; 1.016) |

0.02 |

| Onroad gasoline PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.387 |

1.083 (1.068; 1.097) |

<0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM2.5

|

261,653 |

0.110 |

1.051 (1.038; 1.064) |

<0.01 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM2.5

|

261,653 |

1.090 |

1.033 (1.024; 1.042) |

<0.01 |

| Wood burning PM2.5

|

261,653 |

1.802 |

1.017 (1.009; 1.026) |

<0.01 |

|

Spatial (PAH) or spatiotemporal (NO2) regression models (in Los Angeles County only)

|

| PAH |

114,173 |

6.49 |

0.995 (0.987; 1.004) |

0.30 |

| NO2

|

114,173 |

10.83 |

0.565 (0.535; 0.596) |

<0.01 |

| CALINE4 modeled concentrations |

| UFP number |

352,327 |

6460 |

0.995 (0.989; 1.000) |

0.07 |

| CO |

352,327 |

60.10 |

1.002 (0.996; 1.008) |

0.52 |

| NOx

|

352,327 |

6.06 |

1.007 (1.002; 1.013) |

0.01 |

| Traffic density (odds ratios per 10,000 vehicles per day per meter, within buffers of different sizes) |

| 50 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.998 (0.995; 1.001) |

0.11 |

| 150 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

1.000 (0.998; 1.001) |

0.79 |

| 250 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.997 (0.996; 0.999) |

<0.01 |

| 350 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.997 (0.995; 0.998) |

<0.01 |

|

Road length (odds ratios per 100 m of road length, within buffers of different sizes)

|

| 50 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.993 (0.986; 0.999) |

0.02 |

| 150 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.999 (0.998; 1.000) |

0.13 |

| 250 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.999 (0.998; 0.999) |

0.00 |

| 350 m buffer |

380,951 |

|

0.999 (0.999; 0.999) |

0.00 |

| Distance to roadways |

| Less than 50 m |

381,052 |

|

0.992 (0.984; 1.000) |

0.04 |

| Less than 100 m |

381,052 |

|

0.999 (0.992; 1.007) |

0.89 |

| Less than 150 m |

381,052 |

|

0.991 (0.984; 0.999) |

0.02 |

| Less than 200 m |

381,052 |

|

0.981 (0.973; 0.989) |

0.00 |

| Less than 250 m |

381,052 |

|

0.976 (0.966; 0.985) |

0.00 |

| Less than 300 m |

381,052 |

|

0.974 (0.963; 0.984) |

0.00 |

Associations between PTB and primary PM2.5 (interquartile OR: 1.045; 95% CI: 1.037–1.053) and PM0.1 (interquartile OR: 1.038; 95% CI: 1.009–1.068) modeled at a 4 km × 4 km resolution were weaker than for total PM2.5 but still statistically significant. For sources of primary PM0.1, the strongest associations were observed for onroad gasoline (interquartile OR: 1.096; 95% CI: 1.080–1.112), followed by onroad diesel (interquartile OR: 1.068; 95% CI: 1.055–1.081), and commercial meat cooking (interquartile OR: 1.058; 95% CI: 1.047–1.069), and only a slight positive association was observed for wood burning (interquartile OR:1.009; 95% CI: 1.002–1.016). Patterns by source were similar for primary PM2.5, but overall, associations appear slightly weaker than for PM0.1.

For PM2.5 composition modeled at a 4 km × 4 km resolution, the strongest positive associations with PTB risk were observed for nitrate, ammonium, and SOA, followed by EC, OC, and potassium (K). Slight decreases in risk were associated with calcium (Ca) and strontium (Sr) exposure. No significant positive association was observed for the other chemical species investigated.

No association was observed between PTB and spatially modeled PAH (in Los Angeles County only). NO2 was inversely associated with PTB in this setting.

When primary traffic emissions modeled at fine geographical resolution using CALINE4 were considered, only a slight positive association was observed between PTB and NOx in the entire population (OR per IQR in exposure: 1.007; 95% CI: 1.002–1.013) (Table 6). However, when analyses were restricted to the population in which maternal addresses could be geocoded most accurately (i.e., at the exact parcel centroid), UFP number was slightly but significantly associated with PTB (OR per IQR in exposure: 1.015; 95% CI: 1.000–1.031), whereas the association with NOx had the same magnitude as in the entire population but became insignificant (Appendix C [available on the HEI Web site], Table C.1). With “medium geocoding accuracy,” that is, matching within 50 m of a parcel (leaving about half the population for analyses), positive and significant associations were observed for all three pollutants (PM0.1, CO, and NOx).

Only negative or nonsignificant associations were observed between PTB and traffic density, road length, or distance to roads in the entire population (Table 6). However, for subgroups with better geocoding accuracy, the road traffic indicators had some positive associations with PTB (Appendix C, Table C.2). In the subgroup with medium geocoding accuracy, PTB was positively associated with traffic density in the 50 and 150 m buffers, with road length in the 150 m buffer, and with living within 100 m or 150 m of a roadway. In the small subgroup geocoded at the exact parcel centroid, positive associations with traffic density and distance to roads were observed in even smaller buffers (50 m). Living within 100 or 50 m of a roadway was also associated with an increased PTB risk (Appendix C, Table C.2).

We explored the association between PTB and some air pollution indicators during different time windows: the first month, the first trimester, and the last month of pregnancy. The ORs were higher for exposure averaged over the entire pregnancy (Table 6) than for exposure considered during any of these time windows (Appendix C, Table C.3).

When associations between PTB and exposure averaged on the entire pregnancy were observed in specific subgroups, associations with air pollutant concentrations were typically stronger as the level of maternal education decreased (Appendix C, Table C.4). This pattern was observed—although it was often not statistically significant—for all pollutants except for secondary pollutants (O3, ammonium, nitrates, and sulfates); NO2 using kriging; PM from wood burning; and NOx modeled using CALINE4. No such pattern was observed for traffic density, road length, or residential distance to roadways. In both the PM0.1 and the PM2.5 fractions, interactions were significant for total primary particle mass, OC, and EC, and for primary particle mass from each source. (Although no clear pattern was observed for wood burning, the highest association was observed in mothers with intermediate educational level, that is, from 9th grade to high school.)

When the population was stratified according to quartiles of median income at the census block-group level, the strongest associations between PTB and pollutant concentrations (either modeled or measured) were generally observed in the two lower quartiles of median income rather than in the two upper ones (Appendix C, Table C.5). Interactions by income were significant in both the PM0.1 and the PM2.5 fractions, for total primary particle mass, OC, and EC and for primary particle mass from each source, but also for nitrates and sulfates in the PM2.5 fraction. No significant interaction by income was observed for traffic density, road length, or residential distance to roadways.

Comparison across race/ethnicities showed that the associations between PTB and air pollutant concentrations (either measured or modeled) were generally higher in African American and Hispanic mothers than in white non-Hispanic or Asian mothers (Appendix C, Table C.6). Interactions were significant or close to significance for all air pollutant variables, except for nitrates in PM2.5 and PM from wood burning. However, associations between PTB and traffic density, road length, and residential distance to roadways were always highest in white non-Hispanic mothers and lowest in Asian mothers. Interactions by race/ethnicity were also significant for these traffic indicators.

In mothers with chronic hypertension, associations between PTB and NO2 interpolated with EBK, for primary PM from gasoline, meat cooking, and NOx from traffic modeled using CALINE4 were significantly higher than in those without chronic hypertension (Appendix C, Table C.7). Stronger positive associations in mothers with chronic hypertension than those without this condition were also observed for traffic density, road length, and distance to roads, but this association was significant only for distance to roads. However, a statistically significant, opposite pattern was observed for ammonium and primary PM from wood burning.

Associations between air pollution indicators (measured or modeled concentrations, traffic density, road length, and distance to roads) were generally higher in mothers without diabetes than those with this condition (Appendix C, Table C.8). In both the PM0.1 and the PM2.5 fractions, interactions were significant for total primary particle mass, OC, and EC and for primary particle mass from meat cooking. The interactions were also significant for measured total PM2.5 interpolated with EBK and for ammonium and nitrates in this size fraction.

Analyses by subgroups of BMI at the beginning of pregnancy overall suggest that the higher the BMI, the greater the association between PTB and the concentrations of primary pollutants (Appendix C, Table C.9). The only exception to this trend was in mothers with BMI ≥ 35 at the beginning of pregnancy; this was the smallest subgroup. A similar pattern was also observed for OC in PM2.5. In both the PM0.1 and the PM2.5 fractions, the interactions were statistically significant for NO2, total primary particle mass, EC, and OC. An inverse pattern was observed with some secondary pollutants (O3, nitrates, and ammonium). Interactions by BMI were also statistically significant for these pollutants. Significant interactions by BMI were also observed for CALINE4 predictions and simple traffic indices (traffic density, road length, and distance to roads), but the patterns of associations with BMI were less clear for these air pollution indicators.

Interactions by smoking were significant or nearly significant for only a few air pollutants: Associations were higher in smoking mothers for total PM2.5 and ammonium in PM2.5. However, opposite patterns were observed for O3, CALINE4 predictions, and some road indicators (Appendix C, Table C.10). As described for LBW, only a small number of mothers with PTB infants declared that they smoked. These small numbers might have resulted in an unstable estimate in this subgroup.

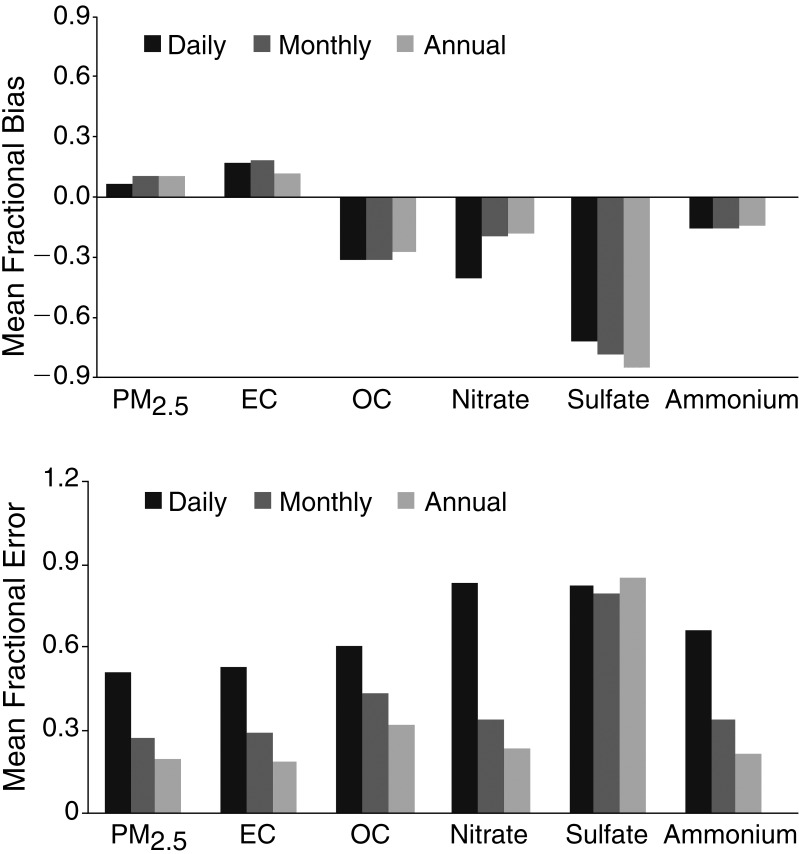

PREECLAMPSIA

For exposure averaged on the entire pregnancy, preeclampsia risk was negatively associated with EBK-interpolated measurements of O3 (interquartile OR: 0.92; 95% CI 0.869–0.974) (Table 7) but not associated with NO2 or total PM2.5.

Table 7.

Associations between preeclampsia and air pollution in California, 2001–2008a

| Air pollution indicator |

Cases |

IQRb

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)c

|

P value |

| Measured pollutant concentrations interpolated by empirical Bayesian kriging (EBK) |

| PM2.5

|

74,011 |

6.49 |

1.002 (0.896; 1.120) |

0.97 |

| O3

|

73,914 |

10.94 |

0.920 (0.869; 0.974) |

<0.01 |

| NO2

|

73,113 |

10.19 |

0.940 (0.820; 1.078) |

0.38 |

|

UCD/CIT modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and species

|

| Primary PM0.1

|

68,551 |

1.366 |

0.970 (0.936; 1.004) |

0.08 |

| OC in PM0.1

|

68,551 |

0.966 |

0.974 (0.942; 1.007) |

0.12 |

| EC in PM0.1

|

68,551 |

0.131 |

0.935 (0.889; 0.983) |

0.01 |

| SOA in PM0.1

|

68,551 |

0.060 |

0.982 (0.901; 1.070) |

0.68 |

| Primary PM2.5

|

68,551 |

8.303 |

0.976 (0.936; 1.018) |

0.26 |

| OC in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

3.664 |

0.984 (0.949; 1.021) |

0.40 |

| EC in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

1.259 |

0.932 (0.884; 0.982) |

0.01 |

| SOA in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

0.229 |

0.986 (0.927; 1.049) |

0.66 |

| Ammonium in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

1.193 |

1.061 (0.993; 1.135) |

0.08 |

| Nitrates in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

2.927 |

1.039 (0.974; 1.109) |

0.25 |

| Sulfates in PM2.5

|

68,551 |

0.530 |

0.940 (0.895; 0.988) |

0.01 |

| UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by species, in PM2.5 |

| K in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.053 |

1.069 (1.025; 1.115) |

<0.01 |

| Cr in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.002 |

0.998 (0.991; 1.004) |

0.48 |

| Fe in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.191 |

1.046 (0.993; 1.101) |

0.09 |

| Ti in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.008 |

1.001 (0.982; 1.020) |

0.93 |

| Mn in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.004 |

No convergence |

NA |

| Sr in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.001 |

No convergence |

NA |

| As in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.001 |

1.001 (0.998; 1.004) |

0.61 |

| Ca in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.048 |

No convergence |

NA |

| Zn in PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.002 |

1.000 (0.991; 1.009) |

1.00 |

|

UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and source

|

| Onroad gasoline PM0.1

|

51,058 |

0.082 |

0.944 (0.874; 1.020) |

0.15 |

| Onroad diesel PM0.1

|

51,058 |

0.070 |

No convergence |

NA |

| Commercial meat cooking PM0.1

|

51,058 |

0.123 |

0.969 (0.922; 1.017) |

0.20 |

| Wood burning PM0.1

|

51,058 |

0.264 |

1.020 (0.995; 1.045) |

0.11 |

| Onroad gasoline PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.383 |

0.964 (0.901; 1.030) |

0.27 |

| Onroad diesel PM2.5

|

51,058 |

0.398 |

1.011 (0.954; 1.072) |

0.70 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM2.5

|

51,058 |

1.090 |

0.989 (0.954; 1.026) |

0.56 |

| Wood burning PM2.5

|

51,058 |

1.759 |

1.035 (1.005; 1.065) |

0.02 |

|

Spatial (PAH) or spatiotemporal (NO2) regression models (in Los Angeles County only)

|

| PAH |

17,675 |

6.53 |

1.033 (0.997; 1.071) |

0.07 |

| NO2

|

17,675 |

11.07 |

0.904 (0.850; 0.961) |

<0.01 |

| CALINE4 modeled concentrations |

| UFP number |

71,522 |

6372 |

0.979 (0.968; 0.990) |

<0.01 |

| CO |

71,522 |

60.28 |

0.971 (0.938; 1.006) |

0.11 |

| NOx

|

71,522 |

6.05 |

0.983 (0.957; 1.010) |

0.22 |

| Traffic density (odds ratios per 10,000 vehicles per day per meter, within buffers of different sizes) |

| 50 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.005 (0.934; 1.081) |

0.89 |

| 150 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.006 (0.966; 1.048) |

0.76 |

| 250 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.005 (0.966; 1.046) |

0.80 |

| 350 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.000 (0.958; 1.043) |

0.99 |

|

Road length (odds ratios per 100 m of road length, within buffers of different sizes)

|

| 50 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

0.998 (0.984; 1.013) |

0.83 |

| 150 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.000 (0.997; 1.003) |

0.89 |

| 250 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

0.999 (0.998; 1.001) |

0.54 |

| 350 m buffer |

75,196 |

|

1.000 (0.999; 1.001) |

0.46 |

| Distance to roadways |

| Less than 50 m |

79,597 |

|

0.987 (0.965; 1.009) |

0.23 |

| Less than 100 m |

79,597 |

|

1.005 (0.986; 1.024) |

0.62 |

| Less than 150 m |

79,597 |

|

1.017 (0.998; 1.037) |

0.08 |

| Less than 200 m |

79,597 |

|

1.002 (0.983; 1.022) |

0.81 |

| Less than 250 m |

79,597 |

|

0.992 (0.971; 1.014) |

0.48 |

| Less than 300 m |

79,597 |

|

1.003 (0.979; 1.027) |

0.82 |

There was no association with primary PM2.5 or PM0.1 modeled at a 4 km × 4 km resolution. For PM2.5 composition, preeclampsia was positively associated with K but negatively with sulfates. Preeclampsia was also negatively associated with EC in both the PM2.5 and the PM0.1 fractions. There was no association with PM from various sources modeled at a 4 km × 4 km resolution, except a positive association with PM2.5 from wood burning.

A positive and nearly significant association was observed between preeclampsia and PAH estimated by spatiotemporal regression (in Los Angeles County only). However, in the same setting, NO2 was inversely associated with preeclampsia.

When we modeled primary traffic emissions at a finer geographical resolution using CALINE4, we found a negative association between preeclampsia and UFPs in the entire population. A significant inverse association was also observed for CO in the subgroup of the population with medium geocoding accuracy (either exact or approximate geocoding to parcel level, which left about half the population for analyses). However, with the most accurate level of geocoding (geocoding at the exact parcel centroid), the significant association disappeared (but the sample size was small) (Appendix D, Table D.1).

The association between preeclampsia and traffic density was more complex (Table 7 and Appendix D, Table D.2). In the entire population, traffic density was not associated with preeclampsia. In the subset with medium geocoding accuracy, associations were generally positive and strongest in the 50 m buffer. However, a significant positive association was only observed in the 50 m buffer in the subset. In the subset with the best geocoding accuracy (at the exact parcel centroid), there were significant positive associations in the 150, 250, and 350 m buffers, but there was no increase in the magnitude of associations from larger to smaller buffers. Associations between preeclampsia and road length in the total population revealed no consistent pattern. Analyses in the subset with the best geocoding accuracy suggested a sharp increase in risk in the 50 m buffer, but the related OR did not reach statistical significance, because of the small sample size. Analyses on residential proximity to roadways in the entire population showed no consistent pattern either.

We explored the association between preeclampsia and exposure to some air pollution indicators during different time windows, and no consistent pattern was observed (Appendix D, Table D.3). For example, when exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy was examined, preeclampsia was negatively associated with NO2 (either interpolated with EBK or based on the spatiotemporal regression model in Los Angeles County) and to primary particles from all sources but not with secondary species in particles (ammonium, nitrates, or sulfates). There was no significant association with total PM2.5 measurements interpolated with EBK during the first trimester. Exposure to ozone and SOA (in either the PM2.5 or the PM0.1 fraction) during the first trimester was associated with an increased preeclampsia risk, whereas no negative associations were documented in the whole population.

Preeclampsia was inversely associated with ozone during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, and with SOA during the third trimester. Preeclampsia was positively associated with ammonium and nitrate, but negatively with sulfates, during the second trimester of pregnancy. A positive association between preeclampsia and PM from wood burning during the third trimester of pregnancy was observed. Still, during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, preeclampsia was negatively associated with NO2 estimated using a spatiotemporal regression model in Los Angeles County and with UFP number also during the third trimester from traffic modeled at fine resolution using CALINE4.

The subgroup analyses revealed few consistent patterns, and many models did not converge. Odds ratios were < 1 in most subgroups and tended to be even lower in the subgroups with the lowest education (Appendix D, Table D.4) and the lowest income (Appendix D, Table D.5), but the interactions were not statistically significant. There was no consistent pattern according to race/ethnicity (Appendix D, Table D.6), although significant interactions were detected for some pollutants, and ORs were even lower in Asians and non-Hispanic whites than in African Americans or Hispanics. Significant interactions by BMI were observed only for distance to roads, but no consistent patterns across categories were observed (Appendix D, Table D.7).

GESTATIONAL DIABETES MELLITUS

Note that GDM data were available only for 3 years of the 8-year study period. When exposures were averaged on the entire pregnancy, GDM was negatively associated with NO2 measurements (but not O3 or total PM2.5) interpolated with EBK (Table 8). GDM was also negatively associated with PM2.5 and PM0.1 modeled at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, whatever the sources and chemical species considered, except for three chemical species (manganese [Mn], arsenic [As], and Ca), for which no significant negative association was observed.

Table 8.

Associations between gestational diabetes and air pollution in California, 2006–2008a

| Air pollution indicator |

Cases |

IQRb

|

Odds ratio (95% confidence interval)c

|

P value |

| Measured pollutant concentrations interpolated by empirical Bayesian kriging (EBK) |

| PM2.5

|

44,952 |

5.38 |

0.907 (0.814; 1.011) |

0.08 |

| O3

|

44,949 |

9.96 |

0.988 (0.932; 1.048) |

0.70 |

| NO2

|

44,772 |

8.77 |

0.822 (0.732; 0.923) |

< 0.01 |

| UCD/CIT modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and species |

| Primary PM0.1

|

42,332 |

1.407 |

0.909 (0.862; 0.959) |

<0.01 |

| OC in PM0.1

|

42,332 |

0.992 |

0.912 (0.868; 0.960) |

<0.01 |

| EC in PM0.1

|

42,332 |

0.145 |

0.875 (0.820; 0.934) |

<0.01 |

| SOA in PM0.1

|

42,332 |

0.058 |

0.965 (0.940; 0.990) |

0.01 |

| Primary PM2.5

|

42,332 |

9.312 |

0.902 (0.840; 0.968) |

<0.01 |

| OC in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

3.892 |

0.907 (0.854; 0.963) |

<0.01 |

| EC in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

1.405 |

0.860 (0.805; 0.918) |

<0.01 |

| SOA in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

0.260 |

0.868 (0.774; 0.974) |

0.02 |

| Ammonium in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

1.243 |

0.869 (0.788; 0.959) |

0.01 |

| Nitrates in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

2.930 |

0.896 (0.809; 0.994) |

0.04 |

| Sulfates in PM2.5

|

42,332 |

0.555 |

0.946 (0.897; 0.996) |

0.04 |

| UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by species, in PM2.5 |

| K in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.198 |

0.861 (0.79; 0.938) |

<0.01 |

| Cr in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

|

No convergence |

NA |

| Fe in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

|

No convergence |

NA |

| Ti in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

|

No convergence |

NA |

| Mn in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.004 |

0.966 (0.932; 1.001) |

0.06 |

| Sr in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.001 |

0.911 (0.865; 0.959) |

<0.01 |

| As in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.001 |

0.994 (0.987; 1.001) |

0.07 |

| Ca in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.051 |

0.960 (0.904; 1.019) |

0.18 |

| Zn in PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.002 |

0.973 (0.952; 0.996) |

0.02 |

| UCD_P modeled concentrations at the 4 km × 4 km resolution, by fraction and source |

| Onroad gasoline PM0.1

|

13,614 |

0.088 |

0.831 (0.743; 0.928) |

<0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM0.1

|

13,614 |

0.080 |

0.870 (0.795; 0.952) |

<0.01 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM0.1

|

13,614 |

0.120 |

0.861 (0.791; 0.937) |

<0.01 |

| Wood burning PM0.1

|

13,614 |

0.285 |

0.954 (0.915; 0.996) |

0.03 |

| Onroad gasoline PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.413 |

0.849 (0.769; 0.937) |

<0.01 |

| Onroad diesel PM2.5

|

13,614 |

0.468 |

0.886 (0.822; 0.956) |

<0.01 |

| Commercial meat cooking PM2.5

|

13,614 |

1.091 |

0.890 (0.833; 0.952) |

<0.01 |

| Wood burning PM2.5

|

13,614 |

1.854 |

0.950 (0.908; 0.995) |

0.03 |

|

Spatial (PAH) or spatiotemporal (NO2) regression models (in Los Angeles County only)

|

| PAH |

8913 |

6.57 |

1.007 (0.954; 1.063) |

0.80 |

| NO2

|

8913 |

10.82 |

1.051 (1.015; 1.089) |

0.01 |

| CALINE4 modeled concentrations |

| UFP number |

42,203 |

6053 |

1.002 (0.984; 1.020) |

0.85 |

| CO |

42,203 |

42.60 |

0.993 (0.971; 1.014) |

0.50 |

| NOx

|

42,203 |

4.49 |

0.982 (0.964; 1.001) |

0.06 |

| Traffic density (odds ratios per 10,000 vehicles per day per meter, within buffers of different sizes) |

| 50 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

0.994 (0.902; 1.097) |

0.91 |

| 150 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.001 (0.948; 1.057) |

0.98 |

| 250 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.025 (0.978; 1.075) |

0.30 |

| 350 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.006 (0.959; 1.054) |

0.81 |

|

Road length (odds ratios per 100 m of road length, within buffers of different sizes)

|

| 50 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.017 (0.996; 1.037) |

0.11 |

| 150 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.001 (0.997; 1.006) |

0.65 |

| 250 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.000 (0.998; 1.002) |

0.83 |

| 350 m buffer |

45,483 |

|

1.000 (0.999; 1.001) |

0.74 |

| Distance to roadways |

| Less than 50 m |

45,486 |

|

0.999 (0.970; 1.029) |

0.95 |

| Less than 100 m |

45,486 |

|

0.987 (0.962; 1.013) |

0.33 |

| Less than 150 m |

45,486 |

|

0.986 (0.960; 1.012) |

0.29 |

| Less than 200 m |

45,486 |

|

1.004 (0.979; 1.029) |

0.77 |

| Less than 250 m |

45,486 |

|

1.007 (0.979; 1.037) |

0.62 |

| Less than 300 m |

45,486 |

|

1.017 (0.984; 1.051) |

0.31 |

No association was observed between PAH estimated by spatially modeled PAH (in Los Angeles County only) and GDM. However, NO2 was positively associated with GDM. No significant association between GDM and CALINE4 estimates of primary traffic emissions was observed, although an inverse association with NOx is close to statistical significance.

Associations between GDM and traffic density were generally positive but not statistically significant, and were strongest in the 250 m buffer. No statistically significant associations were reported in the subgroups with medium and best geocoding accuracy (results not shown).

For road length, a positive (but, again, not significant) association was reported for the 50 m buffer, and no associations were found in the larger buffer sizes. Associations that were not statistically significant were reported in the subgroups with medium and best geocoding accuracy, and no convergence was reached in the 50 m buffer model (results not shown).

Residential proximity to roadways in the entire population showed no consistent pattern. Convergence was usually not reached in subgroups with medium and best geocoding accuracy, probably due to the rarity of observations (e.g., living within 50 or 100 m of a road), because our analyses for GDM were based on 2006–2008 birth records, whereas we used 2001–2008 for other pregnancy outcomes.

We examined the association between GDM and exposure to some air pollution indicators during different time windows (Appendix E, Table E.1). GDM was positively associated with O3 exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy. However, GDM was inversely associated with primary PM exposures that occurred during each of the three trimesters of pregnancy. This was also the case for sulfates, but it was not significant for nitrates or ammonium. GDM was also inversely associated with total PM2.5 interpolated with EBK during the third trimester of pregnancy. GDM was inversely associated with NO2 measurements interpolated with EBK during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, but was positively associated with NO2 estimated using the spatiotemporal regression model in Los Angeles County during the same periods. GDM was inversely associated with NOx exposure estimated using CALINE 4 during the first trimester of pregnancy.

The subgroup analyses revealed few consistent patterns (Appendix E, Table E.3–E.6). Odds ratios were < 1 in most subgroups, and ORs tended to be even lower in the subgroups with the lowest education or the lowest income, but not for traffic density and income.

OTHER PUBLICATIONS RESULTING FROM THIS RESEARCH

Haghighat N, Hu M, Laurent O, Chung J, Nguyen P, Wu J. 2016. Comparison of birth certificates and hospital-based birth data on pregnancy complications in Los Angeles, California. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 16:93; doi:10.1186/sl2884-016-0885-0.

Laurent O, Hu J, Li L, Kleeman M, Bartell SM, Cockburn M, et al. 2016. A statewide nested case–control study of preterm birth and air pollution by source and composition: California, 2001–2008. Environ Health Perspect; Available: http://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/wp-content/uploads/advpub/2016/2/ehp.1510133.acco.pdf. [advance publication 19 February 2016].

Laurent O, Hu J, Li L, Kleeman M, Bartell S, Escobedo L, et al. 2016. Low birth weight and air pollution in California: Which sources and components drive the risk? Environ Int 92–93:471–477.

Li L, Laurent O, Wu J. 2016. Spatial variability of the effect of air pollution on term birth weight: evaluating influential factors using Bayesian hierarchical models. Environmental Health 15:14; doi:10.1186/s12940-016-0112-5.

Young C, Laurent O, Chung J, Wu J. 2016. Geographic distribution of healthy resources and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Matern Child Health J; doi:10.1007/s10995-016-1966-4.

Beltran A, Wu J, Laurent O. 2014. Associations of meteorology with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review of preeclampsia, preterm birth and birth weight. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11:91–172.

Laurent O, Hu J, Li L, Cockburn M, Escobedo L, Kleeman M, et al. 2014. Sources and contents of air pollution affecting term low birth weight in Los Angeles County, California, 2001–2008. Environ Res 134:488–95.

Laurent O, Wu J, Li L, Chung J, Bartell S. 2013. Investigating the association between birth weight and complementary air pollution metrics: a cohort study. Environ Health 12:18.

Laurent O, Wu J, Li L, Milesi C. 2013. Green spaces and pregnancy outcomes in Southern California. Health & Place 24:190–195.

Li L, Wu J, Ghosh J, Ritz B. 2013. Estimating spatiotemporal variability of ambient air pollutant concentrations with a hierarchical model. Atmos Environ 71:54–63.

Li L, Wu J, Wilhelm M, Ritz B. 2012. Use of generalized additive models and cokriging of spatial residuals to improve land-use regression estimates of nitrogen oxides in Southern California. Atmos Environ 55:220–228.

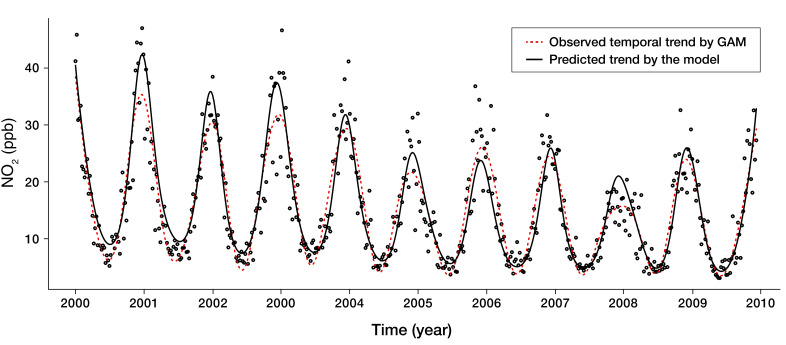

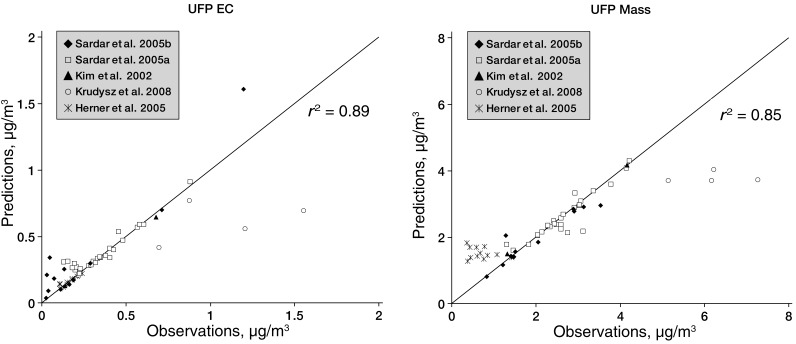

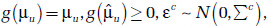

are the covariates, fi(...) is the smooth function consisting of series basis functions (representing the nonlinear relationship), df is degrees of freedom that controls the smoothness of the curve fit, and m is the number of covariates. The variable i represents the index of the covariates (traffic index and meteorological parameters, etc.), u represents spatial location, and c represents spatial autocorrelation in the residual, ε(). For log-transformed concentrations, the link function is

are the covariates, fi(...) is the smooth function consisting of series basis functions (representing the nonlinear relationship), df is degrees of freedom that controls the smoothness of the curve fit, and m is the number of covariates. The variable i represents the index of the covariates (traffic index and meteorological parameters, etc.), u represents spatial location, and c represents spatial autocorrelation in the residual, ε(). For log-transformed concentrations, the link function is  a spatial weight matrix. In other words,

a spatial weight matrix. In other words,  represents spatial autocorrelation that is incorporated into the model.

represents spatial autocorrelation that is incorporated into the model.