Why was the cohort set up?

In the early 1990s, few nationwide representative data on the health of the underage population in Germany was identified. Thus, the Robert Koch Institute (RKI) conducted the ‘German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents’ (KiGGS) as the first nationwide health survey in this population, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health, Federal Ministry of Education and Research, and the RKI. The survey comprised representative data on physical and mental health status, health behaviours and other health determinants based on health examinations and interviews.1 Participants in the KiGGS Baseline study, who all grew up around the turn of the millennium in Germany, are tracked into adulthood, with regular follow-ups, within the KiGGS cohort.2,3 Data from two longitudinal in-depth module studies using sub-samples, the BELLA Study for mental health4 and Motoric Module focusing on motor fitness,5 can be linked to the KiGGS cohort.

The main aims of the KiGGS cohort are to:

identify typical health and health behaviour trajectories over the life course

describe variation in trajectories across different populations

analyse long-term health developments as a function of risk and protective factors

observe transition periods and their implications on health development.

Who is in the cohort?

The Baseline study of the KiGGS cohort was conducted from 2003 to 2006 as the first nationwide health survey among children and adolescents aged 0–17 years with primary residence in Germany.1 A two-stage sampling protocol was used. First, to proportionately consider the population size according to degree of urbanization and geographic distribution in Germany, 167 communities were selected as primary sample units (PSUs), with a disproportionate number of PSUs in Berlin and East and West Germany, to represent these regions separately. Second, an equal number of addresses per birth cohort were randomly selected in each PSU from local population registries. Children and adolescents with non-German citizenship were oversampled by a factor 1.5, to account for expected higher non-response rates6 in this population.

The gross sample included 28 299 minors,6 who were invited to participate in the survey by postal letter sent to their parents or custodians. To maximize participation, non-responding parents were contacted by telephone. Additionally, personal visits were conducted if parents did not respond initially or could not be reached via telephone. Moreover, incentives were used and accompanying local public relations work was carried out prior to the field phase. Migrant-specific activities were conducted to increase participation among children with a migration background.7

After excluding non-eligible cases, the gross sample was N = 26 787, including oversampling, and N = 25 602 without including oversampling. In total, 17 641 respondents were included, with a response rate (RR) 66.6%; this RR refers to the gross (N = 25 602) and net (n = 17 056) sample without oversampling. Referring to the gross (N = 26 787) and net (n = 17 641) sample, including oversampling of children and adolescents with non-German citizenship, the RR was 65.9%. A total of 8985 boys (RR 66%) and 8656 girls (RR 67%) took part in the survey. One study participant requested retrospective deletion of all personal contact and survey data such that 17 640 respondents were finally included in the cohort. There were no differences in the RR with respect to sex and age group. A lower RR was reached among families with non-German citizenship (RR 51%) than among those with German citizenship (RR 68%). Response was lower in major cities (>100 000 residents; RR 58%) than in smaller municipalities (RR 70%). A short questionnaire on basic socio-demographic and health-related information was completed by two-thirds of non-responders. Comparison of basic information between non-responders and responders showed no differences in health indicators. Differences in mothers’ education level suggested a slight middle-class bias.1,6

To yield representative statements, a weighting factor was calculated to account for the clustered sample design and deviations in the net sample from the population structure with respect to age (years), sex, non-German citizenship, federal state (on 31 December 2004) and parents’ highest educational attainment (according to the German Census of 2005).6 Crude and weighted sample characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of baseline socio-demographic and health characteristics of the KiGGS cohort (recruited from 2003–2006)a

| Age, years | 0–2 (N = 2805) |

3–6 (N = 3875) |

7–10 (N = 4148) |

11–13 (N = 3076) |

14–17 (N = 3736) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | %b | % wt** | N | %b | % wt** | N | %b | % wt** | N | %b | % wt** | N | %b | % wt** | |

| Demographics (according to registration office) | |||||||||||||||

| Non-German citizenship | 133 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 316 | 8.2 | 9.3 | 415 | 10.0 | 11.5 | 276 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 339 | 9.1 | 8.9 |

| Region of residence: Western Germany (excluding Berlin) | 1839 | 65.6 | 82.4 | 2571 | 66.4 | 83.9 | 2796 | 67.4 | 86.4 | 2065 | 67.1 | 86.5 | 2470 | 66.1 | 78.1 |

| Municipality size: <5000 | 611 | 21.8 | 16.9 | 866 | 22.4 | 17.6 | 873 | 21.1 | 18.0 | 664 | 21.6 | 18.1 | 792 | 21.2 | 19.3 |

| 5000 to <20 000 | 755 | 26.9 | 24.8 | 1024 | 26.4 | 26.0 | 1108 | 26.7 | 27.2 | 817 | 26.6 | 27.6 | 951 | 25.5 | 27.3 |

| 20 000 to <100 000 | 800 | 28.5 | 29.8 | 1139 | 29.4 | 29.8 | 1218 | 29.4 | 29.6 | 890 | 28.9 | 28.9 | 1119 | 30.0 | 29.4 |

| 100 000 or more | 639 | 22.8 | 28.4 | 846 | 21.8 | 26.7 | 949 | 22.9 | 25.2 | 705 | 22.9 | 25.4 | 874 | 23.4 | 24.0 |

| Demographics (information given by parents) | |||||||||||||||

| Child’s sex: Female | 1389 | 49.5 | 48.7 | 1924 | 49.7 | 48.7 | 2021 | 48.7 | 48.7 | 1488 | 48.4 | 48.7 | 1832 | 49.0 | 48.7 |

| Migration background: | |||||||||||||||

| One-sided | 280 | 10.1 | 11.6 | 317 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 309 | 7.5 | 8.2 | 188 | 6.1 | 7.2 | 198 | 5.3 | 6.1 |

| Two-sided | 361 | 13.0 | 17.6 | 569 | 14.8 | 19.3 | 606 | 14.7 | 18.1 | 487 | 15.8 | 17.9 | 567 | 15.2 | 15.6 |

| Missing | 18 | 32 | 26 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||

| Education of familyc: Low | 355 | 12.8 | 25.3 | 555 | 14.5 | 28.6 | 692 | 16.9 | 33.1 | 566 | 18.7 | 37.0 | 692 | 19.2 | 35.8 |

| Middle | 1616 | 58.3 | 49.4 | 2205 | 57.5 | 48.2 | 2281 | 55.6 | 46.0 | 1676 | 55.4 | 43.8 | 1940 | 53.9 | 44.5 |

| High | 803 | 29.0 | 25.2 | 1076 | 28.1 | 23.2 | 1131 | 27.6 | 20.9 | 785 | 25.9 | 19.2 | 969 | 26.9 | 19.7 |

| Missing | 31 | 39 | 44 | 49 | 135 | ||||||||||

| Socio-economic status of family: Low | 417 | 15.0 | 19.1 | 606 | 15.8 | 20.1 | 681 | 16.6 | 21.4 | 493 | 16.3 | 19.9 | 517 | 14.4 | 18.4 |

| Middle | 1656 | 59.7 | 57.9 | 2270 | 59.3 | 58.6 | 2444 | 59.6 | 59.1 | 1840 | 60.9 | 61.5 | 2191 | 61.2 | 62.5 |

| High | 699 | 25.2 | 23.0 | 955 | 24.9 | 21.3 | 976 | 23.8 | 19.5 | 688 | 22.8 | 18.7 | 873 | 24.4 | 19.1 |

| Missing | 33 | 44 | 47 | 55 | 155 | ||||||||||

| Health status and behaviours | |||||||||||||||

| General health8: Very good/good | 2698 | 97.0 | 97.1 | 3595 | 93.4 | 92.9 | 3888 | 94.4 | 93.9 | 2828 | 93.0 | 92.4 | 3296 | 91.0 | 90.4 |

| Missing | 22 | 25 | 31 | 35 | 114 | ||||||||||

| Children with special health care needs: CSHCN9 Screening positive | 128 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 405 | 11.7 | 11.4 | 645 | 17.0 | 17.0 | 503 | 17.4 | 16.1 | 545 | 15.9 | 15.4 |

| Missing | 220 | 399 | 344 | 241 | 299 | ||||||||||

| Allergic rhinitis (hay fever): Lifetime diagnosis yes | 39 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 226 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 442 | 11.4 | 11.7 | 460 | 16.1 | 15.4 | 680 | 20.0 | 20.0 |

| Missing (refused/‘don’t know’) | 123 | 241 | 271 | 225 | 330 | ||||||||||

| Bronchial asthma: Lifetime diagnosis yes | 15 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 91 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 192 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 215 | 7.1 | 6.6 | 261 | 7.1 | 7.0 |

| Missing (refused/‘don’t know’) | 40 | 60 | 54 | 42 | 51 | ||||||||||

| Atopic dermatitis: Lifetime diagnosis yes | 286 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 616 | 17.0 | 16.4 | 735 | 18.8 | 17.4 | 519 | 18.1 | 17.4 | 568 | 16.6 | 16.5 |

| Missing (refused/‘don’t know’) | 165 | 250 | 245 | 201 | 312 | ||||||||||

| Attention deficit hyperactive disorder: Lifetime diagnosis | yes | 91 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 287 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 255 | 9.0 | 9.1 | 237 | 6.9 | 7.9 | ||

| Missing (refused/‘don’t know’) | 2805 not measured | 275 | 319 | 240 | 305 | ||||||||||

| SDQ-measured mental health problems:10 Total score borderline or abnormal | 691 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 854 | 21.0 | 22.5 | 627 | 20.8 | 21.5 | 557 | 15.5 | 16.7 | |||

| Missing | 2805 not measured | 69 | 75 | 68 | 146 | ||||||||||

| Current smoking: Yes | 124 | 4.1 | 3.4 | 1170 | 31.7 | 33.2 | |||||||||

| Missing | 2805 not measured | 3875 not measured | 4148 not measured | 43 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Obesityd: Yes | 20 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 120 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 269 | 6.5 | 7.1 | 207 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 308 | 8.3 | 9.5 |

| Missing | 1890 (1860 children age <2 years excluded) | 39 | 17 | 12 | 21 | ||||||||||

n = 17 640 because one study participant requested the retrospective deletion of all of their contact and survey data.

Proportion in crude net sample (excluding missing values); wt** = weighted prevalence rates (to German minor population 31 12 2004).

Education groups according to CASMIN (Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Industrial Nations).

Based on national German reference percentiles.11

How often have they been followed up?

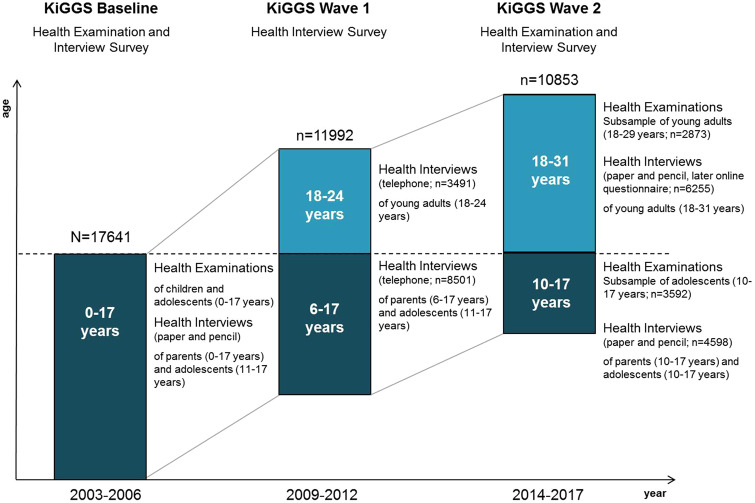

Up to 2018, two follow-ups have been completed (Figure 1). The first follow-up (KiGGS Wave 1) was carried out between 2009 and 2012 as a computer-assisted telephone interview survey.12 At that time, cohort participants were between 6 and 24 years old. The second follow-up (KiGGS Wave 2) was conducted as a health examination and interview survey between 2014 and 2017, with study centres located in the same 167 PSUs as in the KiGGS Baseline study.13 If participants had moved to other communities or they did not want to or could not come to a study centre, they were invited to take part solely in the health interview part, which was conducted using a written questionnaire. To increase response among the young adult (≥18 years) population, online health questionnaires were offered to all young people who had not responded by the end of the health examination period. Participants were 10–29 years old at the time of invitation and ≤31 years old at the time of survey participation.2

Figure 1.

Study design of the KiGGS cohort.

All Baseline study participants were invited to take part in these follow-ups if permission to be contacted again had been given by their parents, or later, by the adult participants themselves. Former respondents for whom permission to be re-contacted was not given, and those who had died or lived permanently abroad, were excluded from invitation. Current addresses were checked using local population registries. Postal invitations and reminder letters were sent. Non-respondents were contacted by telephone and in KiGGS Wave 2 home visits were conducted in the 167 PSUs.

In Wave 1, 11 992 (68%) of the 17 641 Baseline survey respondents participated again (6078 female and 5914 male participants). In Wave 2, 10 853 (62%) cohort members took part in the survey (5790 female and 5063 male participants). For 6465 of these participants (3254 female and 3211 male), additional examination data are available (37% of the Baseline sample).2 For 8979 cohort members (51% of 17 641 Baseline participants), data are available for all three periods of data collection; for 5554 of these participants (31% of the Baseline sample), examination data in Wave 2 are available. A total 1874 participants (11% of Baseline sample) did not take part in Wave 1 but could be included again in Wave 2. A total 3013 persons (17% of the Baseline sample) took part in the Baseline survey and Wave 1 but not Wave 2. A total 3775 Baseline participants (21%) did not take part in either of the two subsequent waves.2

The reasons for non-participation in the two follow-ups are given in Table 2. Only a few participants refused to be contacted again, so a high degree of commitment to the study can be assumed. In total, 33 participants are deceased; it would be necessary to conduct a mortality follow-up to obtain information about the causes of death.

Table 2.

Final disposition codes and loss to follow-up in KiGGS Waves 1 and 2

| Wave 1 | Wave 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Temporary codes | ||

| Non-participation: refusal | 2036 | 2753 |

| Non-participation: no contacta | 2914 | 3562 |

| Non-participation: minimum requirements not metb | 497 | 85 |

| Respondents | 11 992 | 10 853 |

| Sub-total | 17 439 | 17 253 |

| Constant loss (cumulative) | ||

| Retrospective deletion of all contact and survey data, requested by respondent | 1 | 1 |

| Deceased | 16 | 33 |

| Non-participation: permanently living abroad | 99 | 205 |

| Non-participation: unknown addressc | 7 | 8 |

| Non-participation: cohort consent withdrawn | 79 | 141 |

| Sub-total | 202 | 388 |

| Total | 17 641 | 17 641 |

In this article, ‘contact’ is defined as having an interaction with the specific target person. During participant recruitment, it was common to have contact with other (family) members of the target persons’ household. These cases were assigned to the ‘no contact’ category. Therefore, the number of contacts may be underestimated.

Insufficient amount of data and/or missing informed consent.

Research at official residency registries prior to invitation returned status of non-traceable address.

The loss to follow-up in the KiGGS cohort is strongly associated with socio-demographic characteristics. A lower probability of re-participation is associated with older age, male sex, lower socio-economic status (SES) and a migration background (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Loss-to-follow-up in the KiGGS cohort by socio-demographic characteristics; all numbers and percentages are unweighted

| t0: KiGGS Baseline 2003–2006 | t1: KiGGS Wave 1 2009–2012 |

t2: KiGGS Wave 2 2014–2017 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Health examination and interview | Health Interview (Telephone) | Health interview | Subgroup with additional examination | ||||

| Age at t0 | |||||||

| 0–2 years | 2805 | 1929 | 68.8 | 1923 | 68.6 | 1472 | 52.5 |

| 3–6 years | 3875 | 2881 | 74.3 | 2699 | 69.7 | 2082 | 53.7 |

| 7–10 years | 4148 | 3021 | 72.8 | 2527 | 60.9 | 1458 | 35.1 |

| 11–13 years | 3076 | 1986 | 64.6 | 1697 | 55.2 | 747 | 24.3 |

| 14–17 years | 3736 | 2175 | 58.2 | 2007 | 53.7 | 706 | 18.9 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 8986 | 5913 | 65.8 | 5061 | 56.3 | 3211 | 35.7 |

| Female | 8654 | 6079 | 70.2 | 5792 | 66.9 | 3254 | 37.6 |

| Socio-economic status of the family at t0 | |||||||

| Low | 2714 | 1199 | 44.2 | 1179 | 43.4 | 711 | 26.2 |

| Middle | 10 401 | 7292 | 70.1 | 6575 | 63.2 | 3969 | 38.2 |

| High | 4191 | 3396 | 81.0 | 2980 | 71.1 | 1727 | 41.2 |

| Missing | 334 | 105 | 31.4 | 119 | 35.6 | 58 | 17.4 |

| Migration background | |||||||

| No | 13 678 | 9941 | 72.7 | 8926 | 65.3 | 5277 | 38.6 |

| One-sided | 1292 | 799 | 61.8 | 738 | 57.1 | 432 | 33.4 |

| Two-sided | 2590 | 1214 | 46.9 | 1143 | 44.1 | 724 | 28.0 |

| Missing | 80 | 38 | 47.5 | 46 | 57.5 | 32 | 40.0 |

| Total | 17 640a | 11 992 | 68.0 | 10 853 | 61.5 | 6465 | 36.6 |

n = 17 640 because one study participant requested the retrospective deletion of all of their contact and survey data.

Longitudinal weighting factors have been calculated for both follow-ups, to compensate for possible attrition bias owing to differential dropout. Weighting factors were calculated as the cross-sectional weight of the KiGGS Baseline (adjusted to the population as of 31 December 2004) multiplied by a dropout weight. The dropout weight is given by the inverse probability of participation in the follow-up wave. This probability was modelled using a weighted logistic regression model that includes socio-demographic and health behaviour-related indicators as predictors. This weighting results in higher weights for groups that tend to be less willing to participate in the follow-up.

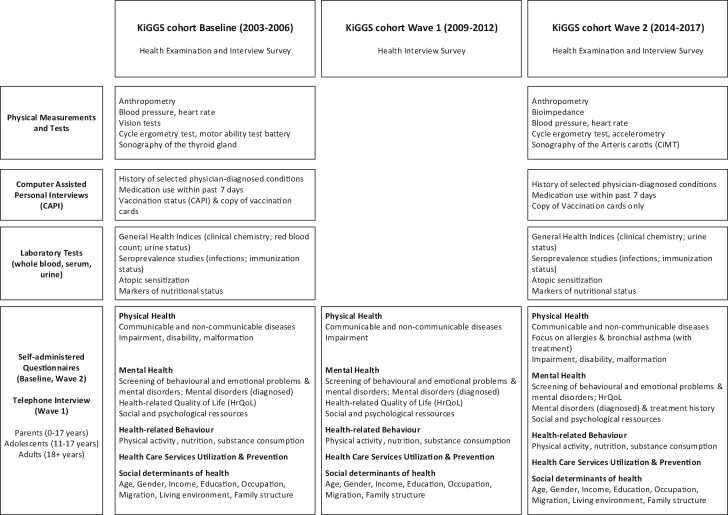

What has been measured?

The KiGGS cohort is characterized by a thematic breadth of collected data, ranging from physical and mental health to health behaviour, psycho-social factors, social background and use of health care services. The survey contents are dependent on the survey modes used in the Baseline survey and the two follow-up waves (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Data collection methods and topics used in the KiGGS cohort across three data collection waves.

Health examination

An age-specific health examination was conducted in the KiGGS Baseline study and KiGGS Wave 2. Measurement of body weight, height and waist circumference14 in both waves was supplemented with analysis of body composition by means of bioimpedance measurement in Wave 2, to observe the development of obesity over the life course. Further anthropometric measurements included head circumference and skinfolds at baseline. As important indicators of cardiovascular health, the resting blood pressure and heart rate were measured in both waves.15 In addition, to identify preclinical arteriosclerosis, sonographic evaluation of the intima-media thickness of the carotid artery wall was implemented in Wave 2. Thyroid size and structure were also examined by ultrasound at baseline. An eye examination was performed, and motor restlessness and skin condition were additionally assessed.

Physical fitness was tested in both waves for children aged 4–10 years using a motor ability test battery to test strength, flexibility, coordination;16 in adolescents and young adults aged 11–29 years, a cycle ergometry test was used to assess cardiorespiratory fitness. Measurement of total physical activity using accelerometry over 7 days was added in Wave 2.

Participants were asked for a blood sample and spot urine sample.17 Electrolytes, transaminases, retention values, blood lipids, thyroid hormone levels, micronutrients, sensitization to common allergens and immune status for selected infections were determined using standardized laboratory methods (see Supplementary data, available at IJE online). To document vaccination status, participants were asked to provide their vaccination records.

Participants’ use of drugs within the last 7 days (prescription and over-the-counter) was registered using a computer-assisted personal interview.18 Data on physician-diagnosed diseases and chronic conditions (allergic diseases such as hay fever, neurodermatitis and asthma; migraine; epilepsy; and heart diseases) were collected in a second computer-assisted personal interview by the study physician in both examination waves. Participants who only took part in the health interview in Wave 2 answered these questions using a self-administered written or online questionnaire.13

Health interview

A broad range of health information was collected using self-administered questionnaires in the Baseline study and Wave 2, whereas a telephone interview was conducted in Wave 1. Age group-specific questionnaires were used. In all waves, questionnaires were administered to parents of participants aged 0–17 years and directly to participants aged 11–17 years. Starting from Wave 1, all information of participants aged ≥18 years was collected exclusively via self-report questionnaires.

As a short assessment of participants’ health status, questions from the Minimum European Health Module8 were included, supplemented with the screening instrument to identify children with special health care needs (CSHCN screener)9 in the Baseline study; other health indicators for physical health were pregnancy conditions, birth weight, premature birth, childhood infectious diseases, pain, accidents, development and maturity, and reproductive health.

Health-related quality of life was measured using the KINDL-R questionnaire19 in the Baseline study for participants aged 3–17 years; in later surveys, this was followed by the KIDSCREEN20 for participants in the same age range and the SF-821,22 for young adults. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)10 was administered to screen mental health problems (for ages 3–17 years) in every wave, complemented by the extended version starting from Wave 1, to include associated impairments.23 Other mental health screening instruments were the SCOFF24 for eating disorders (ages 11–31 years) and subscales of the Patient Health Questionnaire for panic and depressive disorders (ages 18–31 years).25 Preclinical mental health symptoms of young adults were operationalized using two subscales of the 36-Item Short Form Survey SF-36, the Mental Health Inventory MHI-5 and Energy/Vitality.26 At each point in the interviewing process, physician- or psychologist-diagnosed mental disorders were queried.

Personal protective factors were self-reported in all waves using the WIRKALL scale of self-efficacy27 and a short scale of personal resources.28 Social support was measured with the Social Support Scale.29 Personality was operationalized in Wave 2 using a short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-10)30 and well-being in young adults with the Personal Wellbeing Index for Adults (PWI-A).31

Self-reported experiences of violence were recorded in the Baseline study and Wave 1. Retrospective queries about childhood trauma (using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire),32 other adverse childhood experiences (using the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire33), experiences of discrimination, major health events, critical life events such as parents’ separation or death, moving out of the parents’ home, and participants’ own partnership and educational history were included in questionnaires administered to young adults in Wave 2.

Questions on several health behaviours like tobacco use, total physical activity and sporting activities, or use of screen-based media were queried in each survey. Alcohol consumption was operationalized using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Audit-C).34,35 In Wave 2, the European Health Interview Survey-Physical Activity Questionnaire36–38 was implemented among young adults. To measure food intake, a food frequency questionnaire39 was administered in the Baseline study and Wave 2.

Medical care utilization within the last 12 months was queried in all age groups and at all measurement times; this included several medical professions and institutions as well as health insurance. As a special focus in KiGGS Wave 2, information on treatment for diagnosed obesity, bronchial asthma and mental disorders over the lifespan was retrospectively collected.

The KiGGS cohort collects comprehensive information on family and social determinants of health. Questions on household composition, parental marital status and biological siblings were queried in each survey wave; starting from Wave 2, retrospective and current information on blended families can be provided. Familial predisposition to major diseases was assessed by asking about previous diagnoses in participants’ biological parents. Family climate was assessed using a modified version of the Family Climate Scale,40 parenting style with the D-ZKE (The Zurich Short Questionnaire on Parenting Behaviour),41 well-being of parents using the PWI-A31 and parental personality with the BFI-10.30 Duration of out-of-family care during childhood is known for all respondents. Characteristics of the home environment and neighbourhood as well as environmental contamination and noise annoyance were included, especially in Wave 2.

Migration background was operationalized using a multidimensional view. Information collected included nationality, country of birth, year of parents’ immigration and languages spoken at home.7,42 Standardized questions on education, income and employment status of the parents and young adults themselves (ages 18–31 years) were queried.43,44 For young adults, information about educational trajectories and employment over their lifespan was also collected. For participants <18 years old, data on education patterns such as school type, grade, history and performance were collected. As a subjective indicator, subjective social status45,46 was implemented in Wave 2.

A detailed overview of all topics collected in the KiGGS cohort study is given in Supplementary data, available at IJE online.

What has it found? Key findings and publications

The Baseline study of the KiGGS cohort was a population-based cross-sectional health examination and health interview survey that provided nationally representative information on the health of children and adolescents aged 0–17 years living in Germany after the turn of the millennium. KiGGS Baseline study results identified crucial public health-related topics. Overweight and obesity were determined to be an increasing problem. Compared with the results of studies conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, the prevalence of overweight children increased by 50%, and the proportion of obese children and adolescents more than doubled.47 Non-communicable diseases, such as allergies and bronchial asthma,48 emotional and conduct problems,49 and diagnosed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder50 have become more prominent in recent decades. A strong relationship between SES and children’s health was identified for many health indicators,51,52 with lower self-rated health and health-related quality of life and more mental health problems or hazardous health behaviours53,54 among those living in socially disadvantaged families.

To date, two follow-ups of participants in the baseline survey have been carried out within the framework of the KiGGS cohort. After finalizing the data processing for KiGGS Wave 2, trajectories of the main topics of physical and mental health, health behaviours, and their causes and influences can be analysed over the life course. Currently, the first results have been published.

Analysis of laboratory parameters obtained in the Baseline study and Wave 2 showed clear positive transition probabilities among both sexes for allergic sensitization against the allergen mixture SX1, which includes eight common inhalant allergens (defined as specific IgE antibodies with a value of ≥0.35 kU/l) as a main risk factor in the development of allergies, such as hay fever or asthma.55 For the same follow-up period, analysis of preschool children aged 2–6 years at baseline identified a high persistence of obesity in >60% of obese children into their adolescence; overweight showed a higher convertibility.56 Mental health problems in childhood showed high variability as well. These were assessed using the parental version of the SDQ, which classifies respondents with a total SDQ score above the cut-off of the German norm sample as children and adolescents with mental health problems. Only 50% of children and adolescents with mental health problems in the KiGGS Baseline study still displayed symptoms 6 years later in Wave 1.57 Focusing on the development of health or health behaviours during transition periods, we found that adolescence is the critical phase for smoking status in young adulthood; 85% of adolescent smokers continued smoking into young adulthood and approximately nine of ten adult smokers began smoking in adolescence.58 Female sex, lower parental education level and income, and lower motor fitness at baseline were identified as the main predictors of a permanent lack of or intermittent participation in organized sports during the transition from childhood to adolescence.38

Looking at the importance of social and familial environments for health development revealed the importance of one's own education and intergenerational educational mobility for the existence and persistence of health inequalities among young people. Poor self-rated health is less likely to be reported if intergenerational education levels are constantly high or upwardly mobile.59 Another analysis focusing on family structure showed poorer health and higher rates of smoking among adolescents in non-nuclear families, especially those whose parents separated after the Baseline survey.60

What are the main strengths and weaknesses?

The KiGGS cohort study is the only population-based cohort study in Germany to date in which a broad spectrum of health parameters is surveyed, beginning in early childhood and continuing through adolescence and well into adulthood. The sample is large and representative of minors living in Germany at the time of the KiGGS Baseline study. A wide range of topics enable comprehensive analyses of health trajectories and their determinants over the life course. Health interviews are supplemented with objective measurement data obtained by health examinations as well as blood and urine sample collection. Within the next 10 years, all ‘children’ in the KiGGS cohort will have become adults aged from 18 to >40 years. This will permit us to conduct comprehensive analyses of the effects of living conditions of children and adolescents at the turn of the millennium on their health status in adulthood.

A limitation of the study is the long period (5–6 years) between data collection waves. As the survey method changed from written questionnaires to telephone interviews between the Baseline study and Wave 1, possible mode effects must be carefully considered for the indicators analysed. Another restraint is owing to changes in the instruments used, particularly between adolescence and young adulthood. A further limitation is the relatively high dropout rate during the health examination portion of KiGGS Wave 2, owing to the high mobility of young adults combined with restriction of the examinations to those communities originally sampled at baseline. Additionally, reaching majority age has an impact on participation motivation, as parents are no longer part of the decision-making process. In line with other cohort studies, there is a lower willingness to re-participate among young men and those with lower SES or a migrant background. Using the longitudinal weighting factor is assumed to diminish possible effects of selective study participation for variables included in the weighting procedure. However, this can only control for variables collected at the time of KiGGS baseline, not at the time of the follow-ups.

Can I get hold of the data? Where can I find out more?

The dataset of the KiGGS Baseline study is available to interested researchers on application as de facto anonymized data for scientific secondary analysis. The use of longitudinal data of further waves is permitted upon receipt of a informal request and description of the planned project to the ‘Health Monitoring’ Research Data Centre, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany (e-mail: datennutzung@rki.de). Further information and additional study results can be found here: http://www.kiggs-studie.de/english/results.html

Profile in a nutshell

The KiGGS cohort was established in addition to periodically conducted nationwide representative health surveys of children and adolescents aged 0–17 years (KiGGS cross-section) to complement regularly reported trends in prevalence rates among children and adolescents with health development analysis over the life course.

The first population-based nationwide sample of children and adolescents in Germany (KiGGS Baseline study; ages 0–17 years; n = 8656 girls and 8985 boys) was tracked for the first time using telephone health interviews (KiGGS Wave 1: 2009–2012; n = 6079 female and 5913 male participants; re-participation rate 68%). A total of 10 853 participants of the Baseline study (5790 female, 5063 male) completed questionnaires in the health interview of the second follow-up (KiGGS Wave 2: 2014–2017). Additional examination data are available for 6465 of these re-participants (3254 female, 3211 male).

Data were collected using questionnaires, physician-administered personal interviews, health examinations and testing, and laboratory analysis. Topics of the KiGGS cohort include numerous physical and mental health indicators, health behaviours, and health care utilization and personal, familial, environmental and socio-economic health determinants.

Cohort data are available via request with a description of planned projects at Research Data Centre, Robert Koch Institute, Berlin, Germany (e-mail: datennutzung@rki.de).

Funding

The Baseline study of the KiGGS cohort was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Education and Research, and the RKI. After establishing the German Health Monitoring System in 2008, further waves of the KiGGS study were funded by the German Federal Ministry of Health and the RKI only.

Ethics

All studies of the RKI are subject to strict compliance with the data protection regulations of the EU Basic Data Protection Regulation (DSGVO) and Federal Data Protection Act (BDSG). The Ethics Commission of the Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin has reviewed the KiGGS basic survey (No. 101/2000) as well as KiGGS wave 1 (No. EA2/058/09); and the Ethics Commission of the Medizinische Hochschule Hannover has reviewed ethical aspects and approved KiGGS wave 2 (No. 2275-2014). Participation in the studies was voluntary. Participants or their guardians were informed about the aims and contents of the studies as well as about data protection and gave their written consent.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to thank the study participants who took part in the survey, as well as their parents. We would especially like to thank the study teams of all KiGGS waves for their excellent work and their exceptional commitment. The authors wish to acknowledge all of our colleagues from the Robert Koch Institute who played a key role in the development and implementation of the KiGGS cohort and helped to carry out the surveys. A special thank you goes to our former colleague Panagiotis Kamtsiuris, who was instrumental in developing the KiGGS cohort. We thank Analisa Avila, ELS, of Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

References

- 1. Kurth BM, Kamtsiuris P, Holling H. et al. The challenge of comprehensively mapping children's health in a nation-wide health survey: design of the German KiGGS-Study. BMC Public Health 2008;8:196.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lange M, Hoffmann R, Mauz E. et al. KiGGS wave 2 longitudinal component–data collection design and developments in the numbers of participants in the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2018;3:92–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kurth BM, Kamtsiuris P, Hölling H, Mauz E.. Strategien des Robert-Koch Instituts zum Monitoring der Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen. [Strategies of the Robert Koch Institute for monitoring the health of children and adolescents living in Germany]. Kinder-Und Jugendmedizin 2016;16:176–83. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ravens-Sieberer U, Otto C, Kriston L. et al. The longitudinal BELLA study: design, methods and first results on the course of mental health problems. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24:651–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wagner MO, Bös K, Jekauc D. et al. Cohort Profile: The Motorik-Modul Longitudinal Study: physical fitness and physical activity as determinants of health development in German children and adolescents. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1410–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kamtsiuris P, Lange M, Rosario AS.. Der Kinder-und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS): Stichprobendesign, Response und Nonresponse-Analyse. [The German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS): sample design, response and nonresponse analysis]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2007;50:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schenk L, Ellert U, Neuhauser H.. Kinder und Jugendliche mit Migrationshintergrund in Deutschland. [Children and adolescents in Germany with a migration background. Methodical aspects in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2007;50:590–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Bruin A, Picavet HS, Nossikov A.. Health Interview Surveys. Towards International Harmonization of Methods and Instruments Geneva: WHO Regional Publications. European Series, 1996. [PubMed]

- 9. Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newacheck PW.. Identifying children with special health care needs: development and evaluation of a short screening instrument. Ambul Pediatr 2002;2:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Goodman R. The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997;38:581–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kromeyer-Hauschild K, Wabitsch M, Kunze D. et al. Perzentile für den Body-Mass-Index für das Kindes- und Jugendalter unter Heranziehung verschiedener deutscher Stichproben. [Percentiles for the body mass index for childhood and adolescence using various German samples]. Monatsschr Kinderheilkd 2001;149:807–18. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robert Koch-Institut. KiGGS–Kinder-und Jugendgesundheitsstudie Welle 1. Projektbeschreibung. [KiGGS–Study on Health of Children and Adolescents Project Description]. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mauz E, Gößwald A, Kamtsiuris P. et al. New data for action. Data collection for KiGGS wave 2 has been completed. J Health Monit 2017;2:2–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stolzenberg H, Kahl H, Bergmann KE.. Körpermaße bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS). [Body measurements of children and adolescents in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:659–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Neuhauser H, Thamm M.. Blutdruckmessung im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). Methodik und erste Ergebnisse. [Blood pressure measurement in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Methodology and initial results]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:728–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Starker A, Lampert T, Worth A, Oberger J, Kahl H, Bös K.. Motorische Leistungsfähigkeit [Motor fitness. Results of the German health interview and examination survey for children and adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Thierfelder W, Dortschy R, Hintzpeter B, Kahl H, Scheidt-Nave C.. Biochemische Messparameter im Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). [Biochemical measures in the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2007;50:757–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Knopf H. Arzneimittelanwendung bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Erfassung und erste Ergebnisse beim Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). [Medicine use in children and adolescents. Data collection and first results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:863–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ravens-Sieberer U, Bullinger M.. Der Kindl-R Fragebogen zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Revidierte Form [The Kindl-R questionnaire for the assessment of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents. Revised version]. Diagnostische Verfahren zu Lebensqualität und Wohlbefinden. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2003, pp. 184–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20.The KIDSCREEN Group Europe (ed.). The KIDSCREEN Questionnaires: Quality of Life Questionnaires for Children and Adolescents. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beierlein V, Morfeld M, Bergelt C, Bullinger M, Brähler E.. Messung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität mit dem SF-8. [Measuring health-related quality of life with the SF-8]. Diagnostica 2012;58:145–53. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ellert U, Lampert T, Ravens-Sieberer U.. Messung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität mit dem SF-8. Eine Normstichprobe für Deutschland. [Measuring health-related quality of life with the SF-8. Normal sample of the German population]. Bundesgesundheitsbl-Gesundheitsforsch-Gesundheitsschutz 2005;48:1330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goodman R. The extended version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1999;40:791–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH.. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ 1999;319:1467–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL.. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic an severity measure. Psychiatric Ann 2002;32:509–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bullinger M, Kirchberger I, Ware J.. Der deutsche SF-36 Health Survey. Übersetzung und psychometrische Testung eines krankheitsübergreifenden Instruments zur Erfassung der gesundheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität. [The German SF-36 Health Survey. Translation and psychometric testing of a multidisciplinary instrument for the assessment of health-related quality of life]. J Public Health 1995;3:21–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02959944. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Skalen zur Erfassung von Lehrer- und Schülermerkmalen. Dokumentation der psychometrischen Verfahren im Rahmen der Wissenschaftlichen Begleitung des Modellversuchs Selbstwirksame Schulen [Scales for recording teacher and student characteristics. Documentation of the psychometric procedures within the framework of the scientific support of the pilot project “Self-Effective Schools”] Berlin: Freie Universität, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bettge S, Ravens-Sieberer U.. Schutzfaktoren für die psychische Gesundheit von Kindern und Jugendlichen - empirische Ergebnisse zur Validierung eines Konzepts [Protective factors for the mental health of children and adolescents - empirical results to validate a concept]. Gesundheitswesen 2003;65:167–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Donald CA, Ware JE.. The measurement of social support. Res Community Ment Health 1984;4:325–70. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rammstedt B, Kemper CJ, Klein MC, Beierlein C, Kovaleva A.. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der fünf Dimensionen der Persönlichkeit: Big-Five-Inventory-10 (BFI-10) [A short scale to measure the five dimensions of personality: Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10)]. Methoden-Daten-Analysen: Standardisierte Kurzskalen zur Erfassung psychologischer Merkmale in Umfragen 2013;7:233–49. [Google Scholar]

- 31.International Wellbeing Group. Personal Wellbeing Index. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, 2006.

- 32. Klinitzke G, Romppel M, Häuser W, Brähler E, Glaesmer H.. Die deutsche Version des Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) psychometrische Eigenschaften in einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Stichprobe [The German Version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): psychometric characteristics in a representative sample of the general population]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie 2012;62:47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Violence and Injury Prevention. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/questionnaire.pdf?ua=1 (30 June 2014, date last accessed).

- 34. Bradley KA, McDonell MB, Bush K, Kivlahan DR, Diehr P, Fihn SD.. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions: reliability, validity, and responsiveness to change in older male primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1998;22:1842–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA.. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finger JD, Tafforeau J, Gisle L. et al. Development of the European Health Interview Survey-Physical Activity Questionnaire (EHIS-PAQ) to monitor physical activity in the European Union. Arch Public Health 2015;73:59.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baumeister SE, Ricci C, Kohler S. et al. Physical activity surveillance in the European Union: reliability and validity of the European Health Interview Survey-Physical Activity Questionnaire (EHIS-PAQ). Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Manz K, Krug S, Schienkiewitz A, Finger JD.. Determinants of organised sports participation patterns during the transition from childhood to adolescence in Germany: results of a nationwide cohort study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:939.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mensink GBM, Burger M.. Was isst du? Ein Verzehrshäufigkeitsfragebogen für Kinder und Jugendliche. [What do you eat? Food frequency questionnaire for children and adolescents]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2004;47:219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Schneewind K, Beckmann M, Hecht-Jackl A.. Familienklima-Skalen. Bericht [Family Climate Scales. A Report]. München: Institut für Psychologie, Persönlichkeitspsychologie und Psychodiagnostik der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reitzle M, Winkler-Metzke C, Steinhausen HC.. Eltern und Kinder: Der Zürcher Kurzfragebogen zum Erziehungsverhalten (ZKE). [Parents and children. The Zurich Short Questionnaire on Parenting Behaviour]. Diagnostica 2001;47:196–207. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schenk L, Bau AM, Borde T. et al. Mindestindikatorensatz zur Erfassung des Migrationsstatus. [A basic set of indicators for mapping migrant status. Recommendations for epidemiological practice]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2006;49:853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lampert T, Müters S, Stolzenberg H, Kroll LE; KiGGS Study Group. Messung des sozioökonomischen Status in der KiGGS-Studie. Erste Folgebefragung (KiGGS Welle 1). [Measurement of socioeconomic status in the KiGGS study: first follow-up (KiGGS Wave 1)]. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2014;57:762–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lampert T, Hoebel J, Kuntz B, Müters S, Kroll LE.. Socioeconomic status and subjective social status measurement in KiGGS Wave 2. J Health Monit 2018;3:114–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR.. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychol 2000;19:586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Goodman E, Adler NE, Kawachi I, Frazier AL, Huang B, Colditz GA.. Adolescents perceptions of social status: development and Evaluation of a New indicator. Pediatrics 2001;108:e31.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kurth BM, Schaffrath Rosario A.. Die Verbreitung von Übergewicht und Adipositas bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Ergebnisse des bundesweiten Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurveys (KiGGS) [The prevalence of overweight and obese children and adolescents living in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:736–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schlaud M, Atzpodien K, Thierfelder W.. Allergische Erkrankungen. Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder-und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). [Allergic diseases. Results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:701–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hölling H, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U, Schlack R.. Verhaltensauffälligkeiten bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). [Behavioural problems in children and adolescents. First results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:784–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schlack R, Holling H, Kurth BM, Huss M.. Die Prävalenz der Aufmerksamkeitsdefizit-/Hyperaktivitätsstörung (ADHS) bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland. Erste Ergebnisse aus dem Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitssurvey (KiGGS). [The prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) among children and adolescents in Germany. Initial results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS)]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2007;50:827–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lampert T. Soziale Ungleichheit und Gesundheit im Kindes- und Jugendalter. [Social inequality and health in childhood and adolescence]. Pädiatrie 2011;6:119–42. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lampert T, Kuntz B, KiGGS Study Group. Gesund aufwachsen–Welche Bedeutung kommt dem sozialen Status zu? [Growing up healthy-What is the impact of socioeconomic status?]. GBE Kompakt 2015;6 http://edoc.rki.de/series/gbe-kompakt/2015-1/PDF/1.pdf (6 March 2019, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 53. Babitsch B, Götz NA.. Auswirkungen sozialer Ungleichheit auf Gesundheitschancen im Kindes- und Jugendalter und die Herausforderungen für die Präventions- und Versorgungsforschung [Impact of social inequality on health opportunities in childhood and adolescence and the challenges for prevention and care research]. Kinder- und Jugendmedizin 2016;16:167–72. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robert Koch-Institut. Gesundheitliche Ungleichheit bei Kindern und Jugendlichen in Deutschland [Health inequalities among children and adolescents in Germany] Berlin: RKI, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Thamm R, Poethko-Müller C, Thamm M.. Allergic sensitisations during the life course. Results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2018;3:71–5. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schienkiewitz A, Damerow S, Mauz E, Vogelgesang F, Kuhnert R, Schaffrath Rosario A.. Development of overweight and obesity in children. Results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2018;3:76–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baumgarten F, Klipker K, Göbel K, Janitza S, Hölling H.. The developmental course of mental health problems among children and adolescents. Results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2018;3:60–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mauz E, Kuntz B, Zeiher J. et al. Developments in smoking behaviour during the transition from adolescence to young adulthood. Results of the KiGGS cohort. J Health Monit 2018;3:66–70. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Waldhauer J, Kuntz B, Mauz E, Vogelgesang F, Lampert T.. Intergenerational educational pathways and self-rated health during young adulthood: Results of the German KiGGS cohort. IJERPH 2019;16:684.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rattay P, von der Lippe E, Mauz E. et al. Health and health risk behaviour of adolescents—differences according to family structure. Results of the German KiGGS cohort study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192968.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.